Gait ecological assessment in persons with Parkinson’s disease engaged in a synchronized musical rehabilitation program

Introduction

The main motor impairments allowing the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD), rigidity, akinesia, tremor, and postural instability, have an impact on gait. Gait impairments are reflected by a reduction in step length, an increase in cadence, higher variability in postural control, freezing of gait, etc. These walking impairments are among the most disabling symptoms of PD1. A large number of studies have demonstrated the positive effects of physical activity on health parameters and physical capacities of persons with PD (PwPDs), especially gait2,3. Chronic aerobic exercises (dance, Nordic walking, cycling on stationary home trainer, etc.) have also shown positive effects on the progression of motor symptoms4,5,6.

Despite the benefits of chronic aerobic exercises, adherence to the recommended program remains a challenge necessitating the development of highly motivational tools. Music and dance activities are well-suited in this context as they enhance movement and have a high intrinsic motivation impact. The rhythm conveyed by music (e.g., its underlying beat of pulse) has a cueing effect facilitating gait initiation and regularity of step alternation in PD7,8,9. The strong motivating effect of musical rhythmic cueing involves a positive emotional reaction sustained by the activation of reward dopaminergic system activation10,11,12. Overall, music could serve as a powerful tool to enhance movement and promote exercise.

PD is associated with impaired rhythmic skills13. PwPDs are not always able to synchronize correctly their movements to the beat of the music14. A synchronization deficit can induce a deleterious effect of musical cueing on PwPDs’ gait14,15. An adaptive cueing, synchronizing in real-time the music tempo and beats to PwPDs’ steps could allow a beneficial effect even in PwPDs with altered beat perception. An important added value of this approach is to ensure the personalization of the stimulation16.

We recently developed a music-based digital solution called BeatMove (Originally called BeatWalk17, the application has been renamed BeatMove in 2022), able to deliver an adapted music, synchronized in real-time with the PwPDs’ gait. The app delivers interactive musical stimulation, finding the optimal compromise between PwPDs’ individual rhythmic capacities and the stimulus features18. One major functionality of its algorithm is that the music tempo overall stays aligned with the walking tempo at all times, allowing a continuous synchronization (in frequency and in phase) between the step and the musical beat, which maximizes the cueing benefits. The real-time control of the beat-step relative phase is used to attract walkers toward a target cadence which is defined as the cadence measured during the first minute of walking +10%. The temporal gap between the foot landing and the occurrence of the musical beat is finely tuned so that the beat is delivered slightly before each foot contacts the ground, as long as the PwPDs walks at a cadence lower than the target one. As PwPDs increase their step frequency, the gap between beat occurrence and foot contact shortens. This is a subliminal manipulation which allows to reach a target value of +10% of the spontaneous walking cadence, yielding a faster and more stable walking pattern of PwPDs. This parametrization of the system (+10%) allows the best compromise between the maintenance of a given frequency and the tendency of the adaptive stimulus to cooperate. By only partially closing the gap between their cadence and the targeted one, PwPDs could experiment with a significant phase change18. BeatMove, therefore, promotes physical activity through performance feedback (e.g., traveled distance, duration, and number of sessions) and the pleasure of music listening19. It allows PwPDs to walk outdoors while listening to step-synchronized music of various genres. The use of BeatMove for 1-month in the rehabilitation program called BeatPark (The BeatPark rehabilitation program consisted of 30-minute walking sessions, without a cane or human assistance, outdoor, five times a week, for 4 weeks.) has produced an improvement in PwPDs’ performances on a Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), measured in a laboratory setting, before and after this program, in a silent condition17.

In our previous work and in most rehabilitation programs, gait parameters are usually evaluated in the lab, assessing, for instance, motor skills such as speed, step and stride length, and cadence, on a given day at a given time, under a defined treatment, frequently on treadmills, and in constrained and controlled conditions (Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up and Go test, the 10-Meter Walk Test Time, or 6MWT)17,20,21,22. These types of assessments offer no insights into the progression of performance during rehabilitation and fail to reflect the patient’s condition at home.

Other solutions exist to evaluate gait parameters, for example digital wearable devices such as those allowing PwPDs motor skills to be monitored at home23,24,25,26. However, these tools have been mostly used to compare the effect of rehabilitation programs only in the laboratory at baseline and post-intervention27. Digital wearable devices could be valuable for measuring motor skills progression, session by session, to evaluate characteristics of performance variations28. Zajac et al. (2023) recently demonstrated these changes in gait parameters using movement sensors, within sessions during a music-based rehabilitation program29. However, in their study, music was synchronized only in frequency with walking steps, and between-session performances were not evaluated.

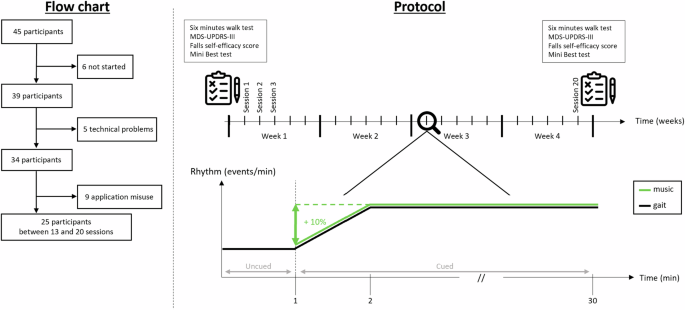

The aim of our study was to measure inter- and intra-session variations in performance over the course of 1 month, as well as to assess the impact of phase and frequency synchronization of music with gait, on gait performance. We collected gait parameters in real life during the 20 rehabilitation sessions of 30 min while participants were listening to music through the BeatMove device (Fig. 1). The variation of performances over time, during sessions, and between sessions allowed us to test the efficacy of BeatMove during the rehabilitation. To validate these results, we also analyzed the 6MWT data. While these results are derived from the study by Cochen De Cock et al. (2021)17, they differ in terms of the subgroup studied and offer a novel interpretation.

The figure consists of three panels: (A) A flow chart summarizing participant numbers throughout the study, detailing reasons for exclusion at each stage, with 25 participants ultimately completing between 13 and 20 sessions. (B) A timeline illustrating the protocol, with 20 sessions distributed over a 4-week period. Two key evaluation points are marked: one at the beginning and one at the end of the study. (C) A detailed view of one session, showing the theoretical progression of rhythm for music (green line) and gait (black line). The session begins with an uncued phase, followed by a cued phase in which rhythmic stimulation aims to achieve a +10% cadence increase.

Results

PwPDs performed on average 17.64 ± 2.46 sessions (range: 13–20), out of the 20 sessions prescribed, and 12 PwPDs completed 100% of the rehabilitation program (20 sessions). The distance traveled was 2.65 ± 0.84 km per session. The mean overall distance traveled in 1 month by a PwPD was 46.44 ± 13.95 km.

Clinical characteristics and gait parameters of PwPDs before and after the rehabilitation program are described in Table 1. The rehabilitation program had a significant positive effect on distance, speed, and step length in the “real life” situation. These real-life measures were obtained with BeatMove during the first silent minute of the first three sessions compared to the first silent minute of the last three sessions. This positive effect was confirmed at the validated 6MWT performed in silence. At the end of the program, the comfortable speed measured during the first minute in silence by BeatMove was similar to the speed at the 6MWT at post-test in the laboratory, where PwPDs received the instruction to walk as fast as possible (1.37 ± 0.53 vs 1.29 ± 0.18, p = 0.47).

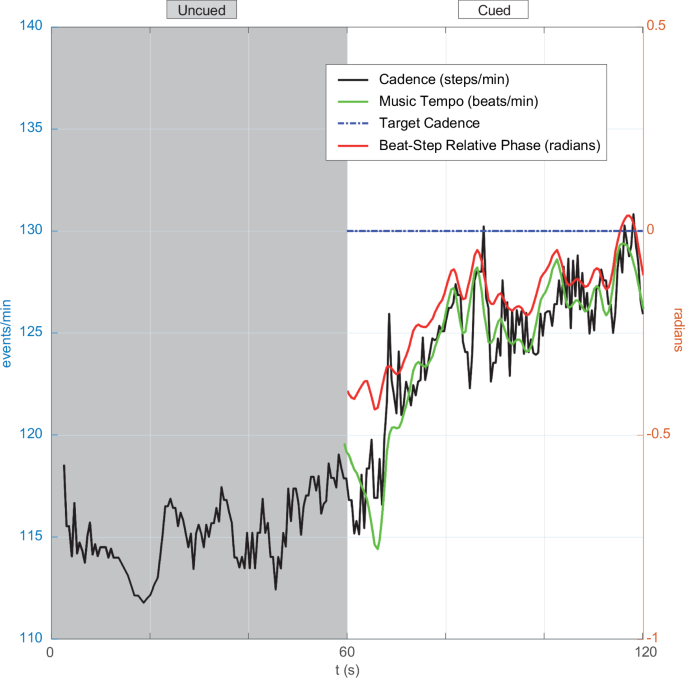

The effect of the adapted musical cueing with BeatMove was measured during the first three sessions, to avoid rehabilitation effects, comparing the first minute (in silence) to the second minute (with music cueing). The adapted musical cueing improved distance, speed, step length, and cadence. Figure 2 shows this effect by depicting an individual’s optimal synchronization of gait cadence to the tempo of the adapted music in real time.

The evolution of cadence (black curve) over the initial 2 min of walking is depicted in one PwPD. The first minute shows the PwPDs spontaneous cadence. The second minute shows the attraction of the cadence by the increasing musical tempo (green curve). At the end of the minute with music, the PwPD has reached the target cadence (blue line) calculated at +10% of the average first-minute spontaneous cadence. The relative phase between the PwPDs’ steps and the beats (red curve) tends towards 0 as the cadence reaches the target cadence.

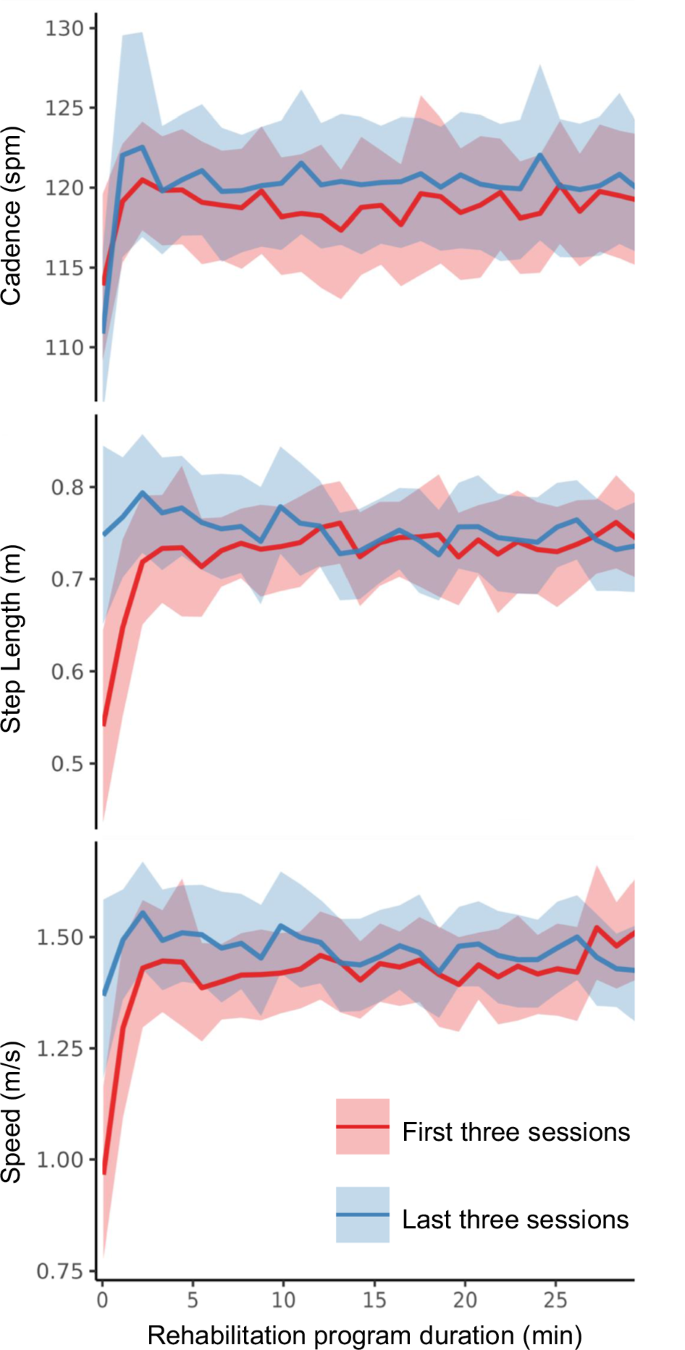

The effects of the 1-month rehabilitation program were evaluated by comparing the first three sessions to the last three sessions (Table 2). The rehabilitation program improved distance, speed, and step length. Figure 3 illustrates these gait parameters averaged for the group, minute by minute. Musical tempo (117.70 ± 10.80 vs. 118.19 ± 9.95, p = 0.65) and cadence remained stable across sessions.

Curves present mean speed, step length and cadence, minute by minute of the three sessions. Shading stands for the 95% confidence interval.

We did not observe any difference in clinical evaluations before and after the program on motor examination (MDS-UPDRS-III), balance (Mini Best Test), and self-reported fear of falling (Falls self-efficacy score).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that our musical application (BeatMove) for individualized gait rehabilitation in PD improved gait parameters measured in a real-life context and in the laboratory with a validated test. This gain is not present only during each session but also along the full rehabilitation program.

Musical cueing induced a major intra-session increase in speed (+34%) from silence to the first minute of stimulation. This increase was linked to an increase in step length (+20%) and gait cadence (+4.6%).

The gait rehabilitation program also increased inter-session speed (+4.3%), as shown by comparing speed values from the first three sessions to speed values from the last three sessions, all with musical stimulation. This effect persisted at the end of the rehabilitation period when walking in silence, as evidenced by the comparison at the fast-paced 6MWT before and after the program (+5.7%). The effect also persisted when walking at a comfortable speed during the program, showing a +41% increase in walking speed during the first silent minute of the last three sessions compared to the first silent minutes of the first three sessions. The speed effect was linked to a sharp increase in step length (+39%) without a change in cadence.

In our real-life situation, cueing relative to silence was associated with an increase in speed by 0.33 m/s (34%), in step length by 0.11 m (+20%), and in cadence by 5.25 steps/min (4.6%). In comparison, previous studies have shown smaller benefits of cueing in laboratory settings: an increase in cadence of 4 steps/minute (4,6%) with a metronome30, and an increase of speed of 0.14 m/s (16%) with music31. Recently, one study with real-life evaluation and adaptive music cueing has shown an increase of 0.13 m/s (12%) and 3.31 steps/minute (3%)29.

After 4 weeks of training, 5 sessions/week, with synchronized music, we obtained an increase in speed of 0.40 m/s (+41%) measured at a comfortable rate. In comparison, one 5 week, 3 sessions/week in silence, rehabilitation program of gait, walking over ground has shown an increase in speed of 0.06 m/s (+5%)32, and a 3-week home music (with predefined tempo) gait training has shown an increase in speed of 0.15 m/s (+25%)33. A controlled study on gait with cueing (metronome and preferred pace), at home and supervised by physiotherapists, has shown an increase in speed of 0.05 m/s22. Another study similar to ours in terms of ecological setting, duration, and training conditions29, has reported an increase in distance at the 6MWT of 12 m (2.5%) compared to 24 m (5.6%) in ours.

The larger increase we noticed in gait parameters during the use of BeatMove, compared to other solutions, could be linked to the motivational effect of real-time phase synchronization with music. Indeed, BeatMove is the only existing device synchronizing music and gait not only in frequency but also in phase, which is a major difference. While both frequency and phase synchronization are important for the successful cueing of biological systems, phase synchronization provides a more detailed and context-specific form of coordination. First, because it ensures that specific events or activities occur at the same point in the oscillatory cycle, it allows for a more precise timing. Second, as it reveals their specific relationships more clearly, it increases the functional connectivity between the two systems, enabling more targeted and efficient communication between them. Third, phase synchronization allows for the transfer of information at specific points in the oscillatory cycle, enabling more efficient and context-specific communication between the two systems. Finally, it increases robustness to frequency variations, making it a valuable mechanism for regulating complex biological processes. The larger increase of speed that we obtained with BeatMove compared to other cueing methods probably results from this step-by-step in-phase synchronization of the musical tempo to the walking cadence34. In practice, whatever the motor state of the PwPD, music will pick him up where he is, even in severe “off” states.

The improvement of speed measured on the 6MWT in silence reaches the threshold (+0.06 m/s) considered as a clinically important difference of speed in laboratory conditions defined by Hass35. This improvement is more important in ecological evaluations (+0.40 ± 0.51 m/s), but this discrepancy can be explained by the measurement conditions. During our 6MWT, PwPDs were asked to walk as fast as possible during the entire test, 6 min. In contrast, in real life, PwPDs were asked to walk at their comfort speed for 1 min. The progress gap is, therefore, wider in this second condition. Moreover, this comfort speed at the end of the program, in silent ecological evaluations, was similar to the speed measured during the 6MWT at the end of the program. The rehabilitation program enabled them to walk at a spontaneous speed as equivalent to their maximum speed in the 6MWT, suggesting that PwPDs were spontaneously walking as fast as possible.

While fatigue could have induced a reduction in speed after 30 min of walking or at the end of the 1-month program, speed still increased, probably linked to the motivational effect of in-phase adaptive music. These results suggest that our BeatPark program duration and intensity were well adapted to our target population.

The main limitation of our study is the lack of a control group. A controlled study is ongoing to confirm these promising results. We quantified the effects of a rehabilitation program efficacy on gait parameters during real-life walking. Our ecological conditions were linked to an important number of participants dropping out of the study. This dropout can be attributed to issues such as non-compliance, problems related to the misuse of equipment or detection techniques, and autonomous use. Despite these challenges, our real-life scenario holds high ecological validity.

Since our inclusion criteria selected PwPDs capable of independent outdoor walking, our results obviously may not be generalized to all PwPDs. Nevertheless, BeatMove could be tailored to accommodate various stages of the disease. To this end, alternative programs with suitable modifications could be designed. For PwPDs with reduced mobility, BeatMove can be used indoors and can still provide synchronized musical cueing. It cannot, however, provide distance-based measurements indoor, as no GPS signal is usually available inside buildings.

The BeatMove application can easily be used independently at home to encourage physical activity and support improvements in muscular and cardiovascular capacities36. It can serve as a complementary tool to physiotherapy when feasible and may even serve as a substitute when physiotherapy is inaccessible due to factors such as distance, cost, or during a pandemic. By being accessible at home, it alleviates the burden on caregivers, easing stricter time, and organizational constraints. Moreover, it offers an alternative to medical therapies for PwPDs who may struggle to accept their illness. The flexibility of schedule of use during the day takes on its full meaning for fluctuating PwPDs, allowing them to choose to opt for a walk when they feel “on”, and even anticipate the onset of an “off” period in an attempt to mitigate it.

With real-time measurement of performances through digital mobility outcomes, PwPDs can track their progress. This can serve as an additional motivational tool to encourage the maintenance of exercise over time. Furthermore, for research purposes this tracking can provide critical data to optimize the duration and intensity of the program37,38,39.

Using music instead of a metronome, with the personalized choice of music genres36 is enjoyable and rewarding10,11,12. Enjoyment is a predictor of physical activity participation and adherence40,41. Reactivating the dysfunctional dopaminergic reward system11 in PwPDs could be especially useful. Musical cueing could induce a restoration of gait rhythmicity, increasing the activity of basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical circuits or activating compensatory cerebello-thalamo-cortical loops19.

Impairment of rhythmic skills is associated, for some PwPDs, with a poor immediate response to rhythmic cues15, likely due to a detrimental dual-tasking effect. Poor synchronization capacities are also associated with a less pronounced longer-term effect of cueing in a rehabilitation protocol14. BeatMove delivers real-time music beats, temporally adjusted to the steps of the PwPDs’ in phase. This synchronized music allows the beneficial effect of cueing in all PwPDs, even those with impaired rhythmic skills18.

The possibility to alleviate motor impairments of PwPDs with auditory cueing is known since the seminal work of Thaut et al. (1993)42. Providing an external clock would be prone to compensated for self-initiated and self-paced movements timing difficulties due to basal ganglia dysfunction. The missing internal cue would be at the origin of PwPDs difficulty to initiate and maintain cyclic movements such as walking43. The explanatory hypotheses which apply to PwPDs’ improved gait performance under the influence of auditory stimulation are twofold and not mutually exclusive: (i) the residual activation of the basal ganglia by auditory cueing, and (ii) the compensatory mechanisms which originate from Supplementary Motor Area (SMA)44,45,46 and/or from the cerebellum45. The existence of compensatory mechanisms, such as the overactivation of the cerebellum47 and motor cortex48 measured with neuroimaging in PwPDs during sensory-motor coordination, raises the question of their evocation by auditory stimulation. In support of these hypothesis, the cerebellar hyper-activation negatively correlated with the activation of the contralateral putamen during auditory-paced movements49,50 and progresses with the disease51.

Healthy individuals’ beat perception ability influences their footstep synchronization with music52. The immediate effect on gait parameters observed during auditory cueing in PwPDs appears to be linked to their rhythmic abilities as measured with the Battery for the Assessment of Auditory Sensorimotor and Timing Abilities (BAASTA)53, and to musical training15. Since the response to the cueing therapy can be predicted by the synchronization performance in hand tapping and gait tasks, the adaptability of the stimulation proposed by BeatMove is a way to address the variability of individual responsiveness.

As encouraging as these results are, a large-sample randomized study is required. It is currently in progress and compares walking in the absence of cueing (effect of physical activity), walking with music but no interactive cueing (assessing the motivating aspect of music), and walking with interactive music (examining the potential reduction in dual-tasking and activation of the reward prediction mechanism).

Phase synchronization of music with gait in PwPDs is a promising rehabilitation tool. BeatMove is a digital mobile device delivering in-phase synchronized music and measuring gait improvements in real-time. Its incorporation in a rehabilitation program such as the BeatPark program improved the walking performance and adherence of PwPDs, likely attributable to its motivational properties.

Methods

PwPDs54 were recruited both from the Department of Neurology of the Beau Soleil Clinic and from the Regional University Hospital of Montpellier (France). Inclusion criteria included the presence of visible gait disorders, however compatible with the ability to walk at least 30 min unaided (Item 10 of the MDS-UPDRS – III ≥ 1 and <3)55 and without freezing, as well as a stabilized treatment 1 month before and throughout the protocol.

Among the 45 PwPDs who were recruited for the BeatPark rehabilitation program17, six did not start the program, and five were not recorded because of technical transmission problems. Data from nine participants were excluded due to application misuse: failure to respect walking time, too many pauses, incorrect position of the sensors, or walking with discharged sensors. Complete data evaluating the effect of the program were therefore available for 25 PwPDs (Fig. 1).

The 25 PwPDs (aged 64.2 ± 8.4; 17 males) who completed the study did not differ from the 20 PwPDs with incomplete or unusable data in terms of age, sex, disease severity (H&Y and MDS-UPDRS III) and treatment (Levodopa). The 25 participants included were kept on their usual medications during the evaluation. Their disease severity was moderate (MDS-UPDRS-III = 27.68 ± 11.46 Hoehn and Yahr stage = 2.44 ± 0.51). Their disease duration was 7.76 ± 4.82 years and their age at onset was 56.44 ± 10.10 years. Their cognitive evaluation on the MOCA was 26.72 ± 2.62. Their levodopa equivalent daily dose was 623.06 ± 387.35 mg56.

The sample size for this study was based on calculations performed during our phase 1 study, which evaluated the efficacy and safety of the BeatMove program17. The current study includes 25 PwPDs with complete data, a number within the range of similar studies that have conducted rehabilitation programs with PwPDs29. As this is an exploratory study, our primary objective was to gather data on the feasibility and potential benefits of the program, rather than to achieve a predetermined statistical power. Our results will be used to guide the design of future studies with larger sample sizes to ensure sufficient power for detecting statistically significant effects.

The study was approved by the National Ethics Committee (CPP Sud Méditérannée III, Nîmes, France, ID-RCB: 2015-A00531-48). The study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02647242). All participants gave their written informed consent before participating in the BeatPark program. Data were anonymized, collected, and registered in a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The BeatPark program consisted of 30-min walking sessions, without a cane or human assistance, outdoors, five times a week, for 4 weeks.

During each session, participants walked first in silence for 1 min, then listened to the adaptive music delivered by BeatMove. They were wearing sensors on both ankles to measure gait parameters and to synchronize the music to their walking phase.

BeatMove modifies the tempo of the music in real-time to match the PwPDs’ gait cadence calculated from the five most recent footfalls18. The first minute served as a pre-test to identify the baseline spontaneous cadence of the participant at each session. The beat of the music is delivered just before the footfall to accelerate the PwPDs’ gait. This phase shift progressively accelerates the tempo of the music to maintain or accelerate the cadence of the PwPDs to at most 10% of the baseline’s cadence18.

Gait parameters were recorded by the BeatMove device during each session. Inertial measurement units (IMU) streamed accelerometer and gyrometer data to the phone via a Bluetooth connection. The placement of the IMU, strapped on each ankle, enabled accurate detection of footfalls by detecting the zero crossing of the sagittal angular velocity of the ankle. The implementation of this step detection algorithm in BeatMove has been validated against force-sensitive resistors connected to the Delsys® Trigno system (Delsys, Boston, USA), which provided the ground truth timing for the heel strike57. IMU placement was not, however, suitable for calculating step length. To this end, the Global Positioning System (GPS) of the phone was used to create a GPS log for distance and velocity measures. Mean step length over 1-min intervals was then computed as the ratio of velocity to cadence. The app logged instantaneous musical tempo and time occurrence of musical beats in the same timeframe as kinematic events. Distance, speed, step length, cadence, and tempo of the music were measured in real-time for each session.

A 6MWT was conducted in the laboratory both before and after the four-week rehabilitation program. During this test, gait spatiotemporal parameters were recorded using sensors (inertial measurement units including 3D accelerometers and gyroscopes, MobilityLab, APDM Inc., Portland) strapped over the feet and anterior side of the left and right tibia, and sternum. Each PwPD was assessed in silence, at the same time of the day, under the consistent treatment condition, and while in the “on” state, approximately one hour after drug intake, to mitigate variations associated with the drug cycle. PwPDs were instructed to walk as fast as possible throughout the duration of the test. Test outcomes are derived from the data collected over the course of the entire six minutes of the test.

Demographic characteristics and medical history were collected in a preliminary interview. Motor severity of the disease was evaluated on the Hoehn and Yahr scale58, and on the revised Movement Disorder Society-Unified PD Rating Scale-part III (MDS-UPDRS-III)55. The levodopa equivalent daily dose was calculated56. Self-evaluation of the risk of falls was provided by the participants using the Falls Self-Efficacy Scale Score59. Balance was evaluated using the Mini-BESTest60. We evaluated global cognitive functioning with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment61.

The motor evaluation (part III) of the MDS-UPDRS, the Falls Self-Efficacy Scale Score, and the Mini-BESTest were performed before and after the 4-week rehabilitation program in the laboratory.

Quantitative variables were presented as means and standard deviations. Results before and after the rehabilitation program were compared using t-student tests. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Responses