Galvanic leaching recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries via low entropy-increasing strategy

Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) play a pivotal role in the global transition to cleaner energy, contributing significantly to achieving a more sustainable planet1,2. Nevertheless, the extensive production of LIBs has consumed 70% of global cobalt (Co) resources3, while the rapid growth of battery waste necessitates urgent disposal strategies4. Consequently, the recycling of spent LIBs is essential for ensuring the continued availability of critical raw materials and supporting the sustainable development of the new energy sector5. Despite recent advancements in traditional metallurgical recycling processes, the lack of systematic cognitive improvement has made it difficult to further improve their thermodynamic efficiency and economic-environmental benefits6. A fundamental principle of thermodynamics dictates that in isolated systems, spontaneous reactions are invariably associated with an irreversible increase in entropy. In terms of LIBs recycling, the high entropy-increasing process will reduce the energy efficiency, promote the release of waste heat and the generation of additional waste, and lead to material mixing, thereby compromising the purity of the recycled products7. Therefore, understanding the process entropy changes is vital for optimizing battery recycling processes in a systematic manner. By designing more efficient recycling processes that minimize entropy production, there is an opportunity to enhance resource recovery while reducing energy consumption and mitigating the economic-environmental burden of the recycling industry.

The positive electrodes of LIBs, abundant in lithium (Li) and Co, are securely bonded to an aluminum (Al) foil carrier using a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) binder to form the positive electrode strip. Conventional recycling methods typically involve crushing and screening to obtain battery powder8, followed by the removal of Al impurities through alkali leaching9, gravity separation10 or color separation11, and ultimately, acid leaching12 to recover the battery metals. Among them, the crushing step disrupts the original structural order of LIBs by mechanical means, thus increasing the system entropy. Meanwhile, the leaching process consumes a large amount of chemicals and water, leading to irreversible energy loss and further contributing to environmental entropy. If the positive electrode strips can be introduced into the acid leaching while preserving their original structure, without prior crushing or additional chemical consumption, the entropy production associated with the recycling process can be substantially reduced. In fact, Al foil has been employed as a zero-valent metal reductant to facilitate efficient reductive leaching of positive electrodes13,14,15. Chernyaev et al.16 and Peng et al.17 reported that Al foil fragments in spent LIB itself could increase the leaching rate of Li and Co from ~80% to ~100%, but due to the side reactions involving hydrogen evolution, their actual consumption is too high. Joulié et al. found that the ternary positive electrodes could be completely dissolved using Al foil fragments as a reducing agent, whereas this required 24 h18. Therefore, while the low entropy-increasing recycling stategy of directly leaching the positive electrode strips appears theoretically feasible, further research is necessary to investigate the impact of hydrogen evolution side reactions on electron reduction efficiency and leaching kinetics within this new system.

Based on the principle of minimum entropy production, this work aims to systematically optimize the hydrometallurgical recycling process for spent LIBs, thereby enabling the efficient and rapid recovery of battery metals. Herein, we demonstrate that the waste LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2 (NCM) electrodes can form a primary cell system with the Al foil current collectors inherent in spent LIBs to induce a targeted transfer of electrons only for the reductive deconstruction of layered NCM electrodes, instead of generating hazardous H2 or releasing organofluorine contamination. We refer to this low entropy-increasing recycling strategy as the galvanic leaching method, which is shown to enhance the recovery rates of Li to over 99% and transition metals to over 90%. More importantly, the electron reduction efficiency is increased by ~25 times, and the leaching kinetics are improved by ~30 times. Environmental-economic assessments further reveal that the galvanic leaching method offers unique advantages in terms of energy saving, carbon reduction and economic benefits, highlighting its potential as a more sustainable and efficient alternative for LIB recycling.

Results

Thermodynamic feasibility analysis and kinetic evidence

We model the NCM electrode materials as a mixture of Ni2O3, Co2O3 and MnO218, and determine the optimal reductant by comparing their Gibbs free energy changes for reacting with different reductants, including H2O2, NaHSO3, and Al foil. The possible reaction equations and their expressions for Gibbs free energy change (({Delta }_{r}{G}_{T}^{{{{rm{theta }}}}})) as a function of temperature (T), are shown in Fig. S1 and Supplementary Note 1. Given that these reactions predominantly occur in aqueous solutions, the reaction temperature range is considered to be 273–373 K19,20. The results indicate that the Gibbs free energy curves for redox reactions using Al foil as a reductant are lower than those of both H2O2 and NaHSO3. It is theoretically proved that the leaching effect of the Al-metal reductant inherent in spent LIBs is better than that of the common external reductants. Furthermore, the Gibbs free energy of each redox reaction of transition metal oxides using Al foil as a reducing agent is lower than that for the hydrogen evolution reactions between Al foil and acid, as shown in Fig. 1a. This suggests that, as long as Al foil is kept in contact with NCM particles, electrons released from Al foil are preferentially transferred to NCM particles, ensuring that the reduction of NCM is completed before any significant hydrogen gas (H₂) generation occurs in the acid solution.

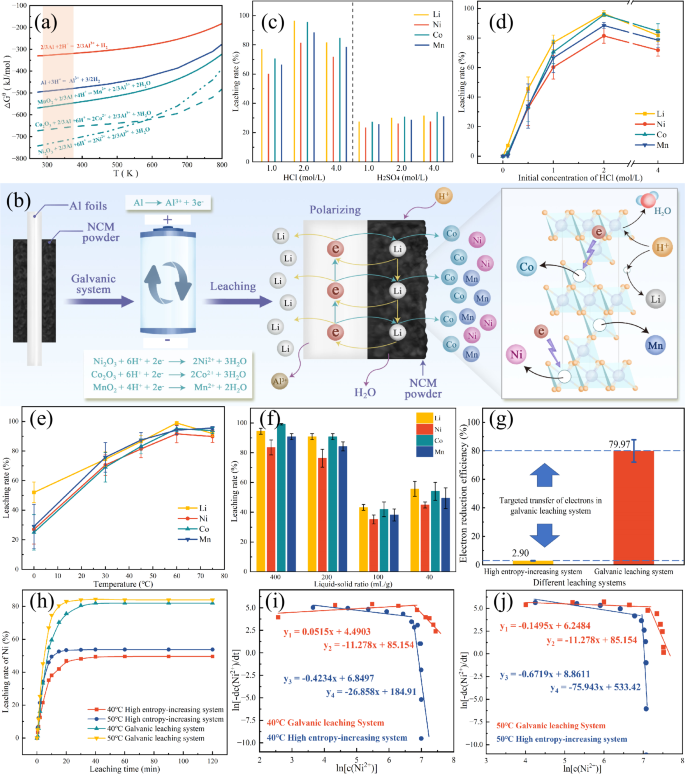

a The thermodynamic analysis based on Gibbs free energy. b The design principle of self-assembly galvanic leaching system from spent lithium-ion batteries. c The actual recovery effect of galvanic leaching systems excited by different concentrations of HCl and H2SO4. Condition optimization of galvanic leaching system from d initial concentration of HCl, e liquid–solid ratio and f leaching temperature. The error bars reflect the standard deviations from at least three individual measurements. The same below. g Electron reduction efficiency under the optimal leaching parameters: 2 mol/L HCl, 200:1 mL/g and 60 °C. h The kinetic leaching rate of Ni. Relationship between kinetic nickel leaching rate and the concentration of Ni2+ in the leachate at i 40 °C and j 50 °C. The error bars in d–g reflect the standard deviations from at least three individual experiments, and the data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m.

The galvanic leaching system in this work involves a series of redox reactions, where the transition metal oxides act as the negative electrode, and the Al foil serves as the positive electrode. In this system, the electrons gained and lost during the reactions are directly transferred through the solid-solid contact surface without adding either a salt bridge or a power supply. We have also calculated the potential (E) of the redox pairs formed by Ni, Co, Mn, Al and their respective oxides, as shown in Table 1, and the corresponding expression is given below:

The specific potential (E) for the reactions of Al with transition metal oxides are as follows:

The potential E of the above three reactions is much higher than the formation boundary value of 0.5 V for the primary cell reaction21,22. From an electrochemical perspective, this substantial potential difference of 2.94–3.84 V forces electrons to preferentially flow through the solid-solid interface, thereby promoting the reduction of NCM electrodes while preventing the generation of hydrogen gas, as shown in Fig. 1b. It is worth noting that the Li+ ions embedded in the NCM electrode will move in the opposite direction to the electron flow, and be attracted by the charge accumulating near the Al foil and tend to gather in close proximity to it. We have also submitted a Supplementary Movie 1 showing the current and voltage measurement obtained using an ammeter in the actual experiments, further demonstrating the viability of the NCM electrodes with the inherent Al foil current collectors in forming a functional primary cell.

It is necessary to note that in the galvanic leaching system, the leaching rates of Li, Ni, Co and Mn elements are 3–4 times higher when using hydrochloric acid (HCl) compared to sulfuric acid (H2SO4), as shown in Fig. 1c. This is because SO42− and Al3+ ions readily form Al2(SO4)3 precipitation, which can adhere to the surface of Al foils and hinder the contact reaction between H+ ions and Al foils, as illustrated in Fig. S2. Detailed condition optimization experiments (Fig. 1d–f) show that under 2 mol/L HCl, 200:1 mL/g and 60 °C, the HCl-induced galvanic system can achieve a Li leaching rate of ~99%, and leaching rates for Ni, Co and Mn of 91.62%, 95.15%, and 94.19%, respectively. More importantly, it is observed that only ~2.90% of the electrons in the high entropy-increasing system (the crushed positive electrode strips from spent LIBs16,17,18) are engaged in the redox reaction of the NCM electrode. This is much lower than the 79.97% electron participation in the galvanic system, representing a 25-fold improvement in electron efficiency, as shown in Fig. 2g. The further leaching kinetics in Figs. S3–4, Tables S1–5 and Supplementary Note 2 show that the activation energies for Ni, Co and Mn drastically decrease from 56.35, 73.95l and 58.51 kJ/mol in the high entropy-increasing system to 31.9, 39.31 and 37.94 kJ/mol in the galvanic system. In contrast, the activation energy for Li increases from 16.94 to 44.70 kJ/mol, due to the charge binding of Li+ ions within the primary cell system. Compared to the high entropy-increasing system, the galvanic system achieves over a 30-fold increase in the dissolution rate of battery metals, such as nickel, at 40–50 °C. Additionally, the high dissolution rate is maintained for a longer period until the end of the reaction, as shown in Figs. 1h–j, S5 and S6 and Supplementary Note 3. Overall, the galvanic leaching system can simultaneously improve the metal dissolution rate and recovery efficiency by increasing the electron reduction efficiency and lowering the reaction activation energy. This improvement is crucial for making the recycling process more efficient and sustainable, contributing to the broader goal of reducing energy consumption and environmental impact in the recycling of spent LIBs.

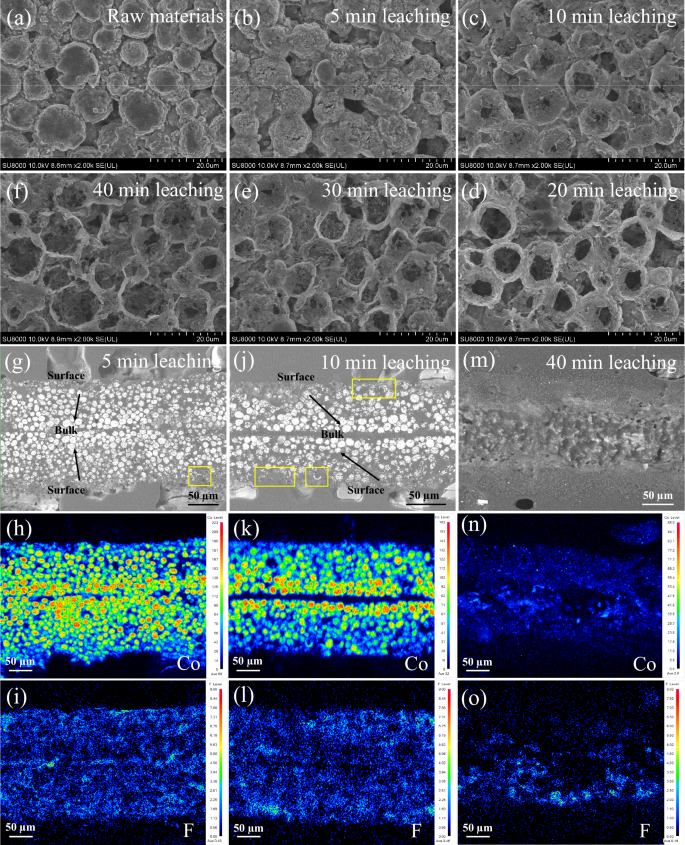

SEM image of NCM particles with galvanic leaching times of a 0 min, b 5 min, c 10 min, d 20 min, e 30 min and f 40 min. g-i are the micro-morphology of particles from the surface to the bulk of NCM electrode strips at a galvanic-leaching time of 5 min, along with the corresponding elemental distribution of cobalt and fluorine, while j–l and m–o represent the situations at leaching times of 10 min and 40 min, respectively. g–i, j–l, and m–o are samples from three parallel experiments, all conducted under the leaching condition of 2 mol/L HCl, 200:1 mL/g and 60 °C. g–o The leached positive electrode strip is placed in a mold with an upright straightener, and then cured with poured epoxy resin to form a hard resin block, and finally is sandblasted and polished to reveal its cross-section.

Morphological and lattice evolution in reductive deconstruction process

The waste NCM electrode particles consist of secondary aggregates of transition metal oxides, exhibiting continuous and smooth surfaces, as shown in Fig. 2a. In the galvanic leaching system, the surface of the waste positive electrode particles firstly undergoes dissolution and cracking (Fig. 2b), and then the dissolution progresses inward, forming cavities within the particles (Fig. 2c). As the galvanic leaching process continues, the cavities inside the particles expand and deepen, as shown in Fig. 2c–e. Eventually, only an organic structural framework, composed of C/F/O-containing components, remains in Figs. 2f and S7. The reason for the emergence of such cavities from the center of particles will be discussed in detail in subsequent sections.

A field emission electron probe micro-analyzer (FE-EPMA) has been employed to characterize the morphological evolution of the entire positive electrode strip from the surface to the bulk, over the course of leaching. The observed morphology in Figure S8 and Supplementary Note 4 reveal that the width of the positive electrode strip initially swells from ~145 µm to ~250 µm, and then shrinks to ~110 µm as leaching progresses. We select Co and F as the representative elements of NCM particles and PVDF binder, respectively. Figure S9 shows that the NCM particles are tightly adhered to the Al foils via the PVDF binder, which corresponds to the positive electrode (middle Al foils) and the negative electrode (NCM particles on both sides) of a primary cell system. The average intensity of Co in the positive electrode strip is 76, while the intensity of F is only 0.53, indicating that a small amount of PVDF-containing organic framework does not completely shield the reaction between NCM particles and HCl. After 5-min leaching, the overall Co content decreases rapidly, as shown in Fig. 2h, and the residual content of Co in the middle is significantly higher than that on the surface. After 10-min leaching, the Co content continues to decrease, as shown in Fig. 2k, and the remaining high Co-containing particles are predominantly enriched on both sides of the middle Al foils. The shell remnants observed on the outer surface of the positive electrode strips in Fig. 2g, j are consistent with the cavity structure described earlier, further confirming that although the Al foil is in contact with the NCM particles internally, the electron transfer through the galvanic reaction leads to the reductive deconstruction of the outer NCM particles. After 40-min leaching, Co elements were almost undetectable, as shown in Fig. 2m-n, proving that the galvanic leaching system can effectively dissolve NCM particles within 40 min.

It is exciting to note that the F-containing PVDF binder can be consistently detected with constant intensity throughout the leaching process, as shown in Fig. 2i, l, o. This indicates that the galvanic leaching system only dissolves the metal materials while leaving the organic structure largely intact. As a result, this system effectively suppresses fluoride contamination in the leaching solution. The remaining binder, with conductive carbon black cured within it, retains its good electrical conductivity, which plays a crucial role in achieving a high electron reduction efficiency (80%) in the galvanic leaching system.

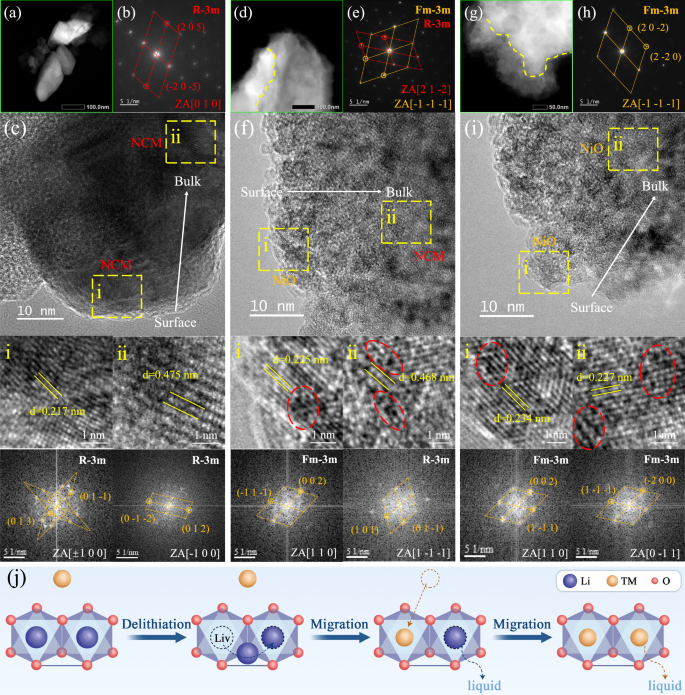

High resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) has been employed to characterize the microscopic transformation of the lattice composition of a single NCM particle from the surface to the bulk at the nanoscale. The high-angle annular dark field-scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images in Fig. 3a, d, g reveal that the electron reflection from high-energy metal inside the raw materials of spent NCM particles is homogeneous. However, after 5-10 min galvanic leaching, a clear shell-kernel delamination phenomenon becomes apparent. The electron diffraction patterns in Fig. 3b, e, h show that, as leaching progresses, the lattice configuration of the spent NCM particles gradually transforms from a lamellar structure characteristic of the original R-3m hexagonal crystal system to a spinel phase, a mixture of R-3m and Fm-3m, and ultimately evolves into a pure rock-salt structure with an Fm-3m face-centered cubic crystal system23,24. The detailed HRTEM images and their corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns of the marked areas in Fig. 3c, f, i and Figures S10–15 suggest that galvanic leaching induces a gradual transformation of the lamellar LiNiO2 lattice of individual NCM particles from the surface to the bulk into a rock-salt NiO lattice. Their interplanar spacing of the lattice decreases from the typical value of 0.48 nm, to about 0.23 nm25,26. Based on this observed lattice transformation, it can be inferred that the substantial potential difference of 2.94–3.84 V (as shown in Fig. 3j) induces the Li+ ions in the layered octahedral unit cell to undergo ionic hopping, resulting in the forming of lithium vacancies27. Concurrently, transition metal (TM) ions with a similar ionic radius occupy these vacancies through the same hopping pathway, leading to the formation of a spinel/rock-salt structure. This enhanced cation mixing accelerates the sequential leaching of both Li+ and TM ions from the crystal lattice into the liquid phase. Furthermore, significant etching pores and grooves emerge between adjacent crystal planes of the NCM particles during the 5–10 min leaching period. The degree of corrosion within the interior of the particles is greater than that on the outer surfaces. This phenomenon is attributed to the current accumulation or charge aggregation inside the particles, caused by the mismatch between the electron transport rate and the crystal reduction rate. This internal charge buildup leads to surface lattice transformation and internal lattice collapse, which is similar to the phenomenon of material expansion, heat generation, and lattice damage caused by reversing the connection of the positive and negative electrodes in a battery28,29,30.

a–c Raw materials of spent NCM particles. d–f 5-min leaching products. g–i 10-min leaching products. a, d, g are HAADF-STEM images. b, e, h are electron diffraction patterns taken directly from TEM equipment. c, f, i are HRTEM image of different leaching products and the corresponding FFT patterns analyzed by Digital Micrograph. j The degradation mechanism of NCM electrodes during galvanic leaching.

Mechanism of the improved metal recovery in galvanic leaching system

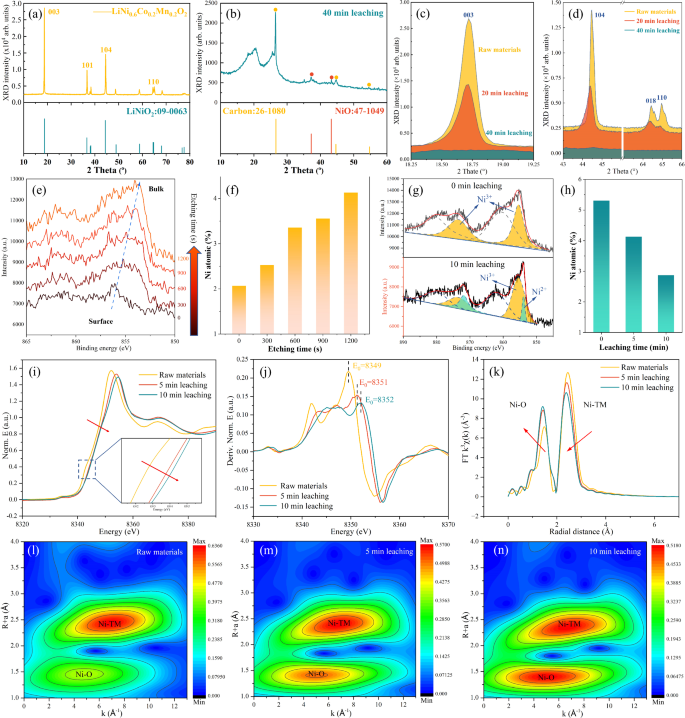

According to the element analysis and X-ray diffractometer (XRD) analysis (Fig. 4a, b), the raw materials are waste LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2 electrodes with a LiNiO2 crystal phase and transformed into a NiO phase with organic residues including carbon black conductor after galvanic leaching31, which is consistent with previous HRTEM analyses. Figure 4c shows that the gradual disappearance of the main (003) peak of the NCM electrodes as leaching time increases, demonstrating the effective deconstruction of the crystal structure by the galvanic leaching system. Local magnified XRD patterns in Fig. 4d show that the (104), (018), and (110) peaks of NCM electrodes decrease and shift towards smaller values of 2θ, indicating stretching and progressive breakdown of the crystal planes in the non-perpendicular directions. This crystal decomposition is a key physical means to improve the leaching of metals from spent LIBs, while the chemical driving force behind this transformation is valence migration. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of Ni 2p, conducted after 0–1200 s etching in Fig. 4e, f, shows that the NCM particles after 5 min galvanic leaching exhibit a trend of valence state transition from +3 to +2 from the surface to the bulk32, with the atomic content of Ni in the bulk being higher than that at the surface. The reason is that the reduced Ni2+ on the particle surface preferentially dissolves into the HCl solution, leaving behind insoluble Ni3+ in the surface layer. To avoid the influence of surface metal dissolution, XPS analysis has been performed 240 nm beneath the particle surface before and after galvanic leaching, as shown in Fig. 4g-h, with each 300-s etching step corresponding to a depth of 60 nm. It shows that a 10 min galvanic leaching is sufficient to reduce the 100% Ni3+ environment inside the NCM particles to a mixture of 25.08% Ni2+ and 74.92% Ni3+, and the Ni content of the 10 min leaching particles is decreased by 48.15%, from 5.4% to 2.8%. These evidences indicate that the 10 min galvanic leaching can dissolve 48.15% of nickel in the surface layer of NCM particles within 240 nm, and reduce 25.08% of the high-valence nickel in the remaining particles to a lower valence state.

XRD pattern of a raw materials and b 40 min leaching products. The local magnification of c 003 peak and d 2θ = 43–66° at different leaching times. e Ni 2p XPS spectra of 5 min leaching products by in-depth etching and f the corresponding Ni atomic percent from the surface to the bulk. g Ni 2p XPS spectra inside raw materials and 10 min leaching products, measured after 1200 s surface etching, respectively. h The atomic percent of Ni inside different leaching products, measured after 1200 s surface etching. i Ni K-edge XANES. j The first derivative of XANES. k Ni K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectra. l–n The 2D contour Fourier-transformed Ni K-edge EXAFS analysis. All leaching products were obtained from galvanic leaching system with the optimal leaching parameters.

The above XPS spectra provide insight into the valence state transitions occurring at the the surface layer of spent NCM electrodes, and in the following, we further investigate the transformation of the internal chemical state of the leaching particles. As illustrated in the Ni K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectrum in Fig. 4i, galvanic leaching induces a notable change in the pre-edge of NCM particles, characterized by a rightward shift. This shift suggests an increase in the Ni²⁺ content within the sample33,34. With the increase of leaching time, the E0 value in the first derivative of the energy edge increases from 8349 eV to 8352 eV (Fig. 4j), which proves the rising oxidation state of Ni in the bulk structure of the galvanic leaching products35. The k3-weighted Fourier transforms of extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectrum in Fig. 4k show that with prolonged leaching, the coordination shell corresponding to the Ni-O scattering path increases, while the coordination shell related to the Ni-transition metal (Ni-TM) scattering path decreases. Combined with the EXAFS fitting parameters in Table S6, it domonstrates that during the galvanic leaching process, the coordination environment of Ni is unstable, and the coordination bonds between Ni and transition metals diminish, gradually transitioning to Ni–O coordination bonds, which can also be confirmed by the 2D contour Fourier-transformed Ni K-edge EXAFS in Fig. 4l–n. Consequently, under a potential difference of up to 3.8 V in the primary battery system, electrons released from Al foil pass through the organic conductor and enter the NCM particles, as shown in Fig. S16. This electron flow leads to preferential reduction and dissolution of the transition metal oxides within the NCM particles, ultimately resulting in the formation of cavity structures, as shown in Fig. 2a–f. It is the electron flow in the surface layer and the charge aggregation within the bulk of the particles that facilitate the reduction of valence states, crystal phase transitions, and alterations in coordination environments of the spent positive electrode particles, from the surface to the bulk. This mechanism underpins the rapid and efficient dissolution and recovery of metals during the galvanic leaching process.

Environmental impact assessment and techno-economic analysis

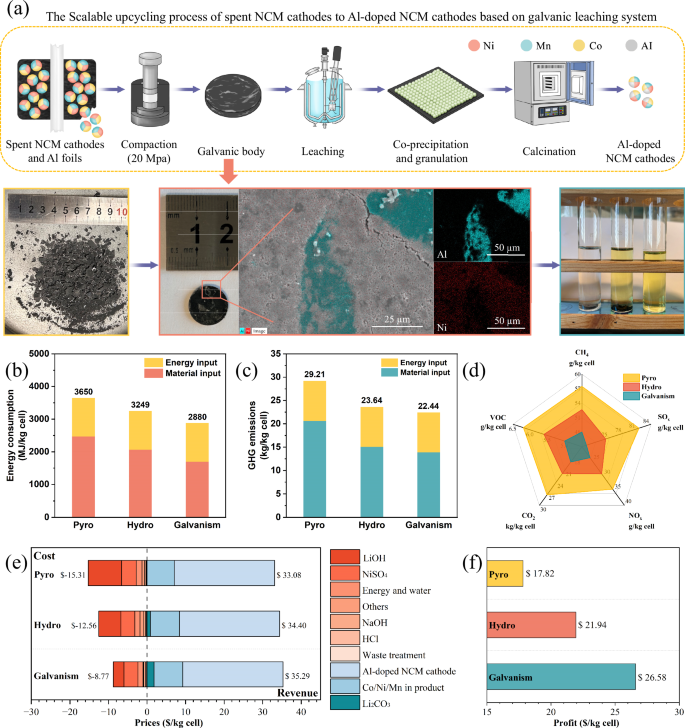

Based on the galvanic leaching principle, we have designed a scalable upcycling process of spent NCM batteries into new Al-doped LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 electrodes, and the simple schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 5a. It should be noted that the process feed is positive electrode strips containing Al foil and partially detached positive electrode powder with LiCoO2 or LiNixCoyMnzO2 (({mbox{x}}+{mbox{y}}+{mbox{z}}=1)) as the crystalline phase, which may originate from manual disassembly of spent LIBs or from positive electrode scraps during battery production. With the improvement of the automated dismantling equipment as shown in Fig. S17 and the increasing attention from more recycling enterprises, the feed source will steadily increase in the near future. The key step of this scalable upcycling process is to compress the crushed NCM electrodes and Al foils into a cake-like galvanic body, which does not cause a significant process entropy change because it does not induce impurity mixing. The industrial computerized tomography images in Fig. S18 show there is extensive close contact between the Al foil and the NCM electrode inside the galvanic body, forming multiple primary cell systems that are similarly arranged in series and parallel order. Thanks to the action of ~20 MPa pressure and the good ductility of Al foil, this galvanic body can withstand the corrosive effects of higher concentration of HCl. Consequently, the liquid-to-solid ratio in the subsequent leaching process can be reduced from 200 ml/g to 10 ml/g, equivalent to a slurry concentration of 100 g/L, and thus the leaching rates of Li, Ni, Co, Mn and Al can be optimized to over 90%. Furthermore, Figs. S19, 20 and Table S7 demonstrate that the regenerated Al-doped NCM electrodes exhibit a dense crystalline state, favorable elemental distribution, and satisfactory electrochemical cycling performance, thereby substantiating the feasibility of this upcycling process of spent LIBs.

a The simple schematic diagram illustrating the scalable upcycling process from spent NCM batteries to new Al-doped LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 electrode materials, and the specific process flow diagram is shown in Fig. S20. b Total energy consumption comparison. c Greenhouse gas (GHG) emission comparison. d Comprehensive comparison of gaseous pollutants. e Cost and revenue of recycling 1 kg of spent LIBs to 1 kg of LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 electrode materials. f The final profit of recycling 1 kg of spent LIBs. $ is in US dollars.

We tried to evaluate the environmental impact and economic feasibility of the galvanic leaching method (Galvanism, Figure S21) for the recycling of spent LIBs through the EverBatt 2023 model36 proposed by Argonne Laboratories in the United States, and compare it with high entropy-increasing strategies including conventional pyrometallurgical (Pyro, Figure S22) and hydrometallurgical (Hydro, Fig. S23) recycling routes, and the obtained data are shown in Tables S8–S13. Conventional pyrometallurgy requires heating the spent LIBs to 800 °C and holding that temperature for 3–5 h to burn off the organic matter and recover metals as alloys. Although this method consumes the least amount of HCl and NaOH, its electrical energy consumption is several times higher than that of hydrometallurgical methods, and thus corresponds to the heavy energy consumption and GHG emissions, which reaches 3650 MJ/kg cell and 29.21 kg/kg cell, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5b, c. Compared with the conventional metallurgical methods, the galvanic leaching system not only inherits the mild reaction conditions of hydrometallurgy, but also requires no external reducing agent, and has the unique advantages of short reaction time and high atomic utilization efficiency, where ~95% Li+ and ~100% Al3+ in spent LIBs will be incorporated into the final regenerated positive electrode materials. Thus it has the lowest energy consumption and GHG emissions, which are 21.10% and 23.18% lower than those of the pyrometallurgical route, and 11.36% and 5.08% lower than those of the hydrometallurgical route. Figure 5d shows the emissions of various gaseous pollutants. It can be found that the emissions of acid gases such as NOx and SO2 from pyrometallurgical route are much higher than those of other methods, while the emissions of VOC, CH4, and CO2 are comparable among these three routes. Figure 5e, f illustrate the product value, energy costs, chemical costs, waste disposal costs and final economic benefits of the three recycling routes. These data suggest that pyrometallurgical method can cause the volatilization loss of lithium ions, reduce the variety and profit of the recycled products, and also necessitate the addition of more expensive chemicals during the remanufacturing of positive electrode materials, resulting in an economic benefit of only $17.82 /kg cell. Moreover, the galvanic leaching method immobilizes fluorinated pollutants in solid waste, which slightly increases the cost of solid waste disposal. However, it significantly reduces the difficulty and amount of wastewater and exhaust gas treatment, while consuming a lower dose of chemicals. Therefore, its economic benefit is satisfactory, reaching $26.58 /kg cell, which is a 49.18% improvement over the pyrometallurgical route, and a 21.14% improvement over the hydrometallurgical route. With the advancement of membrane treatment technologies37,38, the recycling of HCl in acid pickling wastewater will become industrializable in the future, which will further enhance the economic and environmental benefits of this galvanic leaching strategy.

Discussion

Entropy production is an inevitable physicochemical process, and the challenge lies in optimizing these processes to minimize the increase in entropy. The process entropy change associated with the LIBs recycling suggests that crushing and leaching are the main stages contribute significantly to the overall entropy increase. Therefore, this work proposes a short-path leaching approach that eliminates the need for pre-crushing and additional reductants, aiming to achieve efficient and rapid recovery of battery metals under a low entropy-increasing environment. Specifically, the waste LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2 (NCM) electrodes self-assemble with its bonded Al foil current collector to form a complete primary cell system. This configuration effectively confines free electrons, ensuring that they are involved exclusively in solid-phase redox reactions, rather than escaping into the solution and triggering side reactions such as hydrogen evolution. Thanks to a theoretical potential difference of up to 3.84 V, the electron reduction efficiency increases dramatically from 2.90% to 79.97%. The resulting electron flow and charge aggregation are the main reasons for the crystal deconstruction of the positive electrode materials. This electrochemical action does not compromise the integrity of the organic electrolyte structure between NCM electrode particles, which helps to prevent contamination from solid-phase organic fluorides into the liquid phase system. Under optimal conditions, the recovery rates of Li, Ni, Co and Mn are 99.01%, 91.62%, 95.15%, and 94.19%, respectively. Additionally, the metal dissolution rate is increased more than 30-fold, and this high dissolution rate remains nearly constant throughout the reaction. Through the EverBatt 2023 model, this result proves that the energy consumption and carbon emissions of this galvanic leaching strategy are reduced by 11.36%-21.10% and 5.08–23.18%, respectively, compared to conventional metallurgical methods. Moreover, the economic benefit reaches $26.52 /kg cell, representing a 21.37–49.24% improvement. Last but not least, many high-value but difficult-to-recycle urban minerals, such as circuit boards and monitors, face similar high entropy-increasing recycling problem. While shredding is commonly employed due to its simplicity, it significantly complicates subsequent recycling efforts. This study underscores the importance of process entropy management and its potential to drive technological advancements in urban mining, clean production, and the circular economy.

Methods

Raw materials and pretreatment

The raw materials of spent NCM batteries used in this work came from a pure electric vehicle produced by BYD in 2019, which was donated by GEM Corporation, Ltd. Prior to further processing, the spent NCM batteries were subjected to a short-circuiting procedure to reduce their remaining charge to less than 5%. Subsequently, the batteries were immersed in salt water for 48 h to ensure complete discharge14, during which lithium ions (Li⁺) were driven from the graphite electrodes back to the NCM electrodes39. Discharged NCM batteries need to be disassembled in a fume hood, and the intact positive electrode strips should be taken out and ventilated to dry40,41. All the chemicals were analytically pure and were purchased by Tsinghua University. The water used in the experiments was deionized water, which was prepared and quality controlled by the School of Environment, Tsinghua University.

Leaching recovery of spent lithium-ion batteries

In the high entropy-increasing system, the waste NCM electrode strips need to be crushed and dissociated with a shear crusher, and the obtained mixture of NCM electrode powder and Al foil fragments sent to a reactor for acid leaching and dissolution. In a galvanic leaching system, the waste NCM electrode strips are fed directly into the reactor for acid leaching and dissolution, without additional crushing steps. In particular, we explored the theoretical optimum and its mechanism of galvanic leaching by using plastic pins to clamp the positive electrode strip, to prevent separation of the Al foil from the NCM particles. In an expanded application, we granulate the crushed products of spent LIBs, and then leach them with HCl acid; this tight adhesion of the Al foil fragments to the positive electrode particles also produces a leaching effect similar to those of a galvanic leaching system. The preparation method and electrochemical performance testing of the Al-doped LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 electrodes are described in Supplementary Note 5.

Electron reduction efficiency

The electron reduction efficiency is the ratio of the amount of Al dissolved into leaching solution to the total amounts of Ni, Co, and Mn, and can be used to quantitatively analyze the electron targeted transfer involved in redox reactions. With LiNixCoyMnzO2 (x + y + z = 1) as the active component, NixCoyMnz is regarded as the equivalent of Me(III), i.e., LiMeO2. The main reaction in the leaching process is shown as:

The side reaction in the leaching process is shown as:

The electron reduction efficiency α is calculated by the following equation, and since the amount of electrons transferred per reaction of 3 mol LiMeO2 is the same as that of the reaction of 1 mol Al, the correspondence is regulated by the coefficient 3:

where nAl and nMe represent the amounts of Al and the sum of the amounts of Ni, Co and Mn in the leaching solution, respectively, and their units are mol. The sum of the amounts of Ni, Co and Mn represents the amount of electrons involved in the main reaction, while three times the amount of Al represents the total amount of electrons released from Al foils. As α gets closer to 1, it shows that more Al foils are directly involved in the reduction of the high-valent transition metal oxides, while a smaller α represents that more Al is involved in the side reaction. It should be noted that the quality of the Al foil and positive electrode powder in the raw materials used in this study are shown in Fig. S24. Calculations indicate that the molar ratio of Al is ~18% excessive. As the thickness and quality of Al foil in commercial LIBs continue to decrease42, this ratio will gradually decrease, which also means that this galvanic leaching strategy will remain effective for a long time to come.

Material characterization

A field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Hitachi SU-8010, Japan) was employed to capture the surface morphology of NCM electrodes and organic framework during the galvanic leaching process. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, PerkinElmer, OPTIMA 2000, USA) was employed to analyze the concentration of dissolved metals to calculate the elemental composition. XRD (Philips PW 1700, USA) was employed to explore the lattice evolution during the galvanic leaching process. In order to capture the coupling characteristics of the Al foils and the NCM particles, we took out the NCM electrode strips during the galvanic leaching process, cured them into the resin, and sanded and polished them to expose the smooth cross-section as shown in Fig. S25. FE-EPMA (8050G, Shimadzu, Japan) was employed to analyze the element content on these smooth cross-sections, to obtain the elemental distribution of remaining NCM particles and Al foils. XPS (Thermo Fisher, Escalab 250Xi, USA) with an argon ion etching gun was used to explore for changes in elemental valence states in the surface layer of particles from the surface to the bulk, under a monochromated Al Kα source and at an energy of 1486.6 eV. XANES analysis was supported by Hefei Light Source, and the obtained XAFS data was processed in Athena for background, pre-edge line and post-edge line calibrations.

Responses