Genotoxic consequences of viral infections

Introduction

Many aspects of viral infections are not directly related to the action of the virus in question. Complications associated with infections can be permanent or curable. One critical aspect of post-viral complications is the genotoxic effects of certain viruses. Genotoxicity refers to the ability of certain agents, including viruses, to damage the genetic material within host cells, potentially leading to cell dysfunction and cancer development. Genotoxic viruses, including HIV1, human papillomavirus (HPV)2, hepatitis B and C3, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)4, and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)5, can integrate their genetic material into the host genome, resulting in mutations. HPV plays a significant role in the development of cervical cancer6, while hepatitis B and C viruses are major causes of liver cancer7. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is associated with several types of lymphoma8 Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is linked to Kaposi’s sarcoma, a type of cancer that forms in the lining of blood and lymph vessels9.

The mechanisms of genotoxicity encompass a range of processes that result in direct or indirect damage to the DNA molecule10. Direct DNA damage can be defined as the formation of adducts, or direct chemical bonds to DNA; DNA strand breaks, which disrupt the integrity of the genome; and DNA alkylation, where alkyl groups added to DNA lead to abnormal replication. Indirect DNA damage may result from the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which oxidize the nitrogenous bases of DNA, or from the inhibition of DNA repair mechanisms, thereby increasing the likelihood of mutation. Errors in the replication of DNA may be caused by intercalation, whereby chemical compounds occupy the space between DNA base pairs, resulting in replication errors. Furthermore, chromosomal abnormalities, including chromosomal aberrations (deletions, duplications, translocations, inversions) and aneuploidy (alterations in chromosome number), are also induced by genotoxic agents11.

The role of DNA damage in host cells in the life cycle of viruses is complex, with effects varying depending on the virus type, replication mechanism and host response. A multitude of viruses have evolved intricate mechanisms to exploit or manipulate host DNA damage response (DDR), frequently utilizing these pathways to enhance replication, evade immune defenses, or establish persistent infections12. While DNA damage can impede viral replication by disrupting essential cellular processes, it can also facilitate viral propagation by activating pathways that viruses exploit for their own replication13.

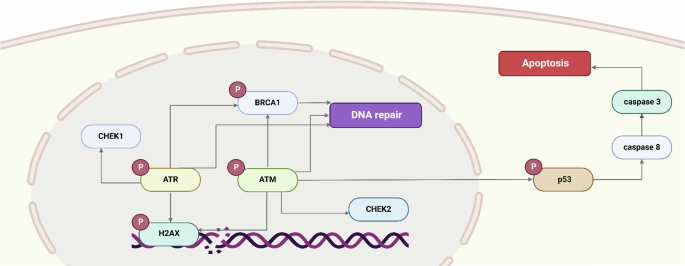

In the event of DNA damage, cells initiate a series of repair mechanisms collectively known as DDR (Fig. 1). However, this activation presents a potential challenge for DNA viruses, as it can result in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, thereby limiting viral replication14. To counteract this, several DNA viruses have developed strategies to interfere with key DDR signaling proteins, such as ATM and ATR kinases, which are crucial for the detection and repair of DNA breaks15,16.

Figure illustrates the DNA damage response (DDR) pathway, highlighting the sequential activation of key kinases, including ATM, ATR, CHEK1, BRCA1, and CHEK2, in response to DNA damage. If DNA damage is irreparable, the pathway culminates in apoptosis.

Retroviruses such as HIV have been observed to employ specific strategies for interacting with the DDR, which significantly impacts their replication processes17. During the course of an HIV infection, the integration of viral DNA into the host genome involves the participation of DNA repair enzymes, which can result in the triggering of a DNA damage response in the host cell. HIV effectively exploits DDR components, such as the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway, to enhance the efficiency of its integration and establish a long-term presence within the host genome, creating latent reservoirs that contribute to persistent infections18.

Furthermore, DNA damage resulting from viral infections can prompt host cells to adopt a state that is conducive to viral replication or persistence. Persistent DNA damage may result in the induction of cellular senescence or the activation of chronic inflammation, thereby creating an environment that is conducive to the replication of certain viruses. For example, cytomegalovirus (CMV) exploits cellular senescence to establish latency, exploiting this altered cellular state to evade immune detection and enabling reactivation under conditions of immune suppression19,20.

In the present review, we evaluate how different viruses induce genotoxic stress, their interaction with the DNA repair machinery, and finally, how this may lead to potentially oncogenic consequences, e.g. mutations and/or chromosomal aberrations. We excluded directly oncogenic viruses like papilloma and hepatitis B viruses from this review as comprehensive reviews already exist on this subject21,22.

RNA viruses

Human immunodeficiency virus

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified human immunodeficiency virus, type 1 (HIV-1) as a “carcinogenic to humans” (Group 1) agent, indirectly associated with the cancer risk via immunosuppression23. HIV leads to a gradual depletion of CD4+ T cells and eventually, if left untreated, leads to a severe immune deficiency, so-called acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)24. Despite combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) that blocks HIV replication and restores CD4+ T cell counts, people living with HIV experience a high prevalence of certain types of malignancies25. In a comprehensive study of the North American population, cumulative incidences (%) of cancer by age 75 (HIV+/HIV−) were: Kaposi sarcoma (KS), 4.4/0.01; non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), 4.5/0.7; lung, 3.4/2.8; anal, 1.5/0.1; colorectal, 1.0/1.5; liver, 1.1/0.4; Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), 0.9/0.1; melanoma, 0.5/0.6; and oral cavity/pharyngeal, 0.8/0.826.

Here we shall focus our attention on the possible direct effects of HIV-1 on DNA integrity and efficiency of DNA repair.

Studies in people living with HIV

HIV infection triggers oxidative stress and oxidative DNA damage in both infected and non-infected cells. CD4+ T cells from people living with HIV have significantly increased levels of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine, a metabolite of oxidized DNA, as compared to HIV-negative people, with particularly high levels in people with AIDS27. Spontaneous H2O2 production by monocytes from people with HIV is higher than in healthy controls and correlates with the viral load28. B cells from cART-treated people living with HIV have a higher level of reactive oxygen species and a higher level of DNA damage29. 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine levels are increased in frontal cortex autopsy tissue from HIV-positive individuals with or without HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders as compared to HIV-uninfected controls30. Moreover, the level of mitochondrial DNA 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from people with HIV correlates with HIV-related structural brain changes seen by magnetic resonance imaging of the brain: lateral ventricular enlargement and decreased volumes of the hippocampus, pallidum, and total subcortical gray matter31. Serum/plasma levels of oxidative stress markers, such as lipid peroxidation or malondialdehyde adducts, are higher in people living with HIV, while plasma levels of antioxidants, including glutathione, are lower32,33,34. The frequency of micronuclei, a marker of genome instability, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is also increased in people with HIV35. Taken together, these findings suggest that HIV-1 actively stimulates the oxidative stress response and DNA damage in different cell types.

Genotoxicity of HIV-1 proteins

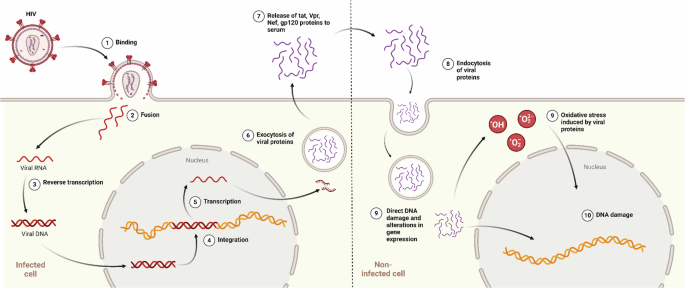

The persistence of certain diseases in people living with HIV despite successful HIV infection control with cART may be at least partially attributed to ongoing viral protein synthesis (Fig. 2). Although cART successfully inhibits viral replication, latent HIV-infected cells are not eradicated and persist even after long-term effective cART, which makes a cure difficult to achieve36. Furthermore, while cART blocks many stages of the HIV-1 cycle, it has little effect on the transcription or translation of viral genes. The HIV LTR promoter is never completely silent37,38 and even defective proviral DNA in infected cells can give rise to viral proteins39,40, which may have an impact on HIV-associated illnesses.

The figure depicts the process of genotoxicity triggered by HIV-1 proteins. The proteins are released from infected cells through exocytosis and subsequently enter healthy cells, where they induce oxidative stress. This oxidative stress leads to DNA damage, including double-strand breaks and chromosomal aberrations. Arrows indicate protein trafficking pathways.

One of such potentially pathogenic proteins is HIV-1 Tat (trans-activator of transcription), a crucial player in viral transcription and pathogenesis. HIV-1 Tat binds to nascent viral RNA element (TAR, transactivation-responsive region) and recruits activated transcriptional factors to the viral promoter, which leads to increased viral transcript elongation41,42. Tat is efficiently released from HIV-infected cells43,44 and can penetrate non-infected cells through endocytosis45. Tat can also be released extracellularly within exosomes46. Due to this property, Tat is considered to play a role in several HIV-associated pathologies, such as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, substance use disorder, cardiovascular complications, accelerated ageing, B cell lymphomas, and others47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56. Tat circulates in the blood50,57,58,59,60 and cerebrospinal fluid61 of people with HIV. Oncogenic properties of Tat have been proposed in different cancers62,63,64,65.

Tat triggers oxidative stress in T cells66,67, B cells29, brain endothelial cells68,69,70, neuronal71,72,73, microglial74,75 and astroglial76 cells. Furthermore, Tat protein modulates the expression of multiple genes involved in DDR and DNA repair. In T cells, HIV-1 Tat downregulates TP53 expression77. Human rhabdomyosarcoma cells expressing Tat are more sensitive to radiation due to a decreased expression of DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), an enzyme that participates in the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway of DNA repair18. In rat pheochromocytoma cells, Tat downregulates Ku70, another crucial component of NHEJ, and upregulates Rad51, a central enzyme in homologous recombination (HR) DNA repair. This results in a diminished capacity for rejoining linearized DNA but an enhanced HR-mediated DNA double-strand breaks repair78. The cellular protein Tip60 (Tat-interacting protein), initially identified as an interactor of HIV-1 Tat, has emerged as a significant research focus due to its involvement in diverse cellular processes, including chromatin remodeling, DNA damage response and repair, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis79. Tat inhibits Tip60’s histone acetyltransferase activity80 and induces its polyubiquitination and degradation81. These actions may impair Tip60-mediated cellular DNA damage signaling and repair.

The impact of Tat protein on B cells warrants particular attention, given the increased incidence of B-cell lymphomas in people living with HIV82. While HIV-1 cannot directly infect B cells, the ability of its Tat protein to enter these cells and interfere with DNA repair mechanisms is believed to contribute to lymphomagenesis. The presence of Tat protein was detected in HIV-1-associated B-cell lymphomas, including Burkitt’s lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma83,84,85. In vitro, exposure of B cells to Tat results in the emergence of chromosomal aberrations, including through the mechanisms of oxidative stress, depletion of glutathione levels, and DNA damage29,86. However, other mechanisms may also be involved. HIV-1 Tat upregulates the expression of error-prone DNA polymerase β in B cells, a known mutagenic enzyme that is also upregulated in AIDS-related B cell lymphoma lineages87. HIV-1 Tat protein induces the transcription of the nuclease-encoding RAG1 gene in B cells, leading to the formation of DNA double-strand breaks, including double-strand breaks in the MYC gene locus50. This increase in double-strand breaks promotes the colocalization of the MYC gene locus with the IGH gene locus, ultimately contributing to the characteristic t(8;14) chromosomal translocation associated with Burkitt’s lymphoma50. Loci colocalisation is an important prerequisite for chromosomal translocation between them88,89,90. MYC and IGH colocalisation is increased in circulating B cells from people with HIV50. Tat also activates the expression of the AICDA gene through Akt/mTORC1 pathway activation and inhibition of the AICDA transcriptional repressors c-Myb and E2F8; AICDA gene encodes the activation‐induced cytidine deaminase (AID), an enzyme that in physiological conditions creates double-strand breaks for immunoglobulin class‐switch recombination and immunoglobulin gene maturation in B cells. Overexpression of AID leads to increased double-strand breaks within the IGH and potentially MYC gene loci, favouring the formation of t(8;14) translocation91,92. Therefore, Tat protein is a potentially significant factor contributing to B-cell lymphomagenesis in HIV-positive individuals through its ability to induce genome instability.

HIV-1 accessory protein Vpr is another potentially pathogenic and genotoxic protein that can actively or passively enter the extracellular compartment and interact with uninfected bystander cells93,94. Extracellular Vpr is detected in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of HIV-positive individuals95,96. Similar to HIV-1 Tat, Vpr can induce oxidative stress and deplete glutathione levels97,98,99. In infected cells, Vpr exhibits a complex interplay with the host DNA damage response machinery, displaying both activating and inhibitory effects100,101. Vpr directly induces DNA damage, leading to the formation of both double-strand breaks and single-strand breaks100,102. Vpr also induces double-strand DNA unwinding, leading to the accumulation of negatively supercoiled DNA and the recruitment of topoisomerase 1, ultimately resulting in DNA double-strand breaks103. These DNA lesions trigger the recruitment of repair factors, such as γH2AX, RPA32, and 53BP1, to initiate the DNA damage response signaling cascade100. Vpr triggers expression upregulation, activation, and recruitment of DNA damage response proteins (Rad17, Hus1, ATR, RPA70)103,104. DNA damage and the consequent activation of the DNA damage response are ubiquitous inducers of cell cycle arrest at the G2 phase, and Vpr has been demonstrated to effectively trigger G2 phase cell cycle arrest105,106,107,108,109,110. However, Vpr also possesses DDR-inhibitory properties, antagonizing essential DSB repair mechanisms like HR and NHEJ100. Vpr targets and triggers a proteasomal degradation of a wide array of host DNA damage response proteins, including UNG2, SMUG, HLTF, MUS81, and EME1 components of the SLX4 complex, EXO1, TET2, MCM10, and SAMHD1111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119. This suggests that Vpr’s DNA damage response-associated functions may be compartmentalized during the viral life cycle within an infected cell. This dual nature of Vpr’s DNA damage response modulation suggests a potential role in promoting genomic instability and facilitating viral integration into the host genome. Extracellular Vpr also exhibits the capacity to elicit a DNA damage response upon transduction of target cells120.

HIV-1 Nef (Negative regulatory factor), another potential pathogenic viral protein, is released from infected cells in microvesicles (exosomes) and circulates in the plasma of HIV-infected individuals even with viral suppression therapy121,122,123,124. Nef prolongs the survival of the infected T cells by interacting with the signal transduction proteins of the host cells. It can encourage the endocytosis and destruction of receptors found on cell surfaces like CD4 and MHC proteins, as well as the death of uninfected T cells. This reduces the ability of cytotoxic T cells to aid the virus in eluding the host’s defenses. The HIV Nef genes are necessary for effective viral transmission and disease progression in vivo but not for HIV replication in vitro. In vitro, Nef has been demonstrated to cause monocyte-derived dendritic cells to overexpress the B lymphocyte stimulator BLyS and to move from infected macrophages into B cells via actin-propelled conduits123,125. HIV-1 Nef exhibits pro-oxidant activity in microglial, endothelial cells, and neutrophils126,127,128,129. Nef promotes p53 proteasomal degradation130. Similarly to Tat, Nef upregulates AICDA and promotes DNA double-strand breaks in B cells, contributing to genomic instability131. Nef is also the primary cause of lung cancer in HIV-positive individuals, whose lung cancer develops on average ten years earlier than in non-infected individuals. Lung cells were shown to express more of the essential angiogenesis-promoting protein vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) and to be more proliferative and invasive when Nef was present132. Nef has been demonstrated to work in collaboration with the human herpesvirus 8 protein K1 in Kaposi sarcoma to stimulate angiogenesis and cellular proliferation via the miRNA-718-mediated phosphatase and tensin homolog/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PTEN/AKT/mTOR) pathway133.

HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein 120 (gp120) is detectable in the serum, in secondary lymphoid organs, and in the brain of people living with HIV134,135,136,137. gp120 is implicated in AIDS-related neurotoxicity and is partially responsible for HIV-1 attachment to target cells. gp120 induces oxidative stress in astrocytes, brain, and endothelial cells68,138,139. Further evidence that gp120’s neurotoxicity is mostly indirect, and comes from the requirement for extremely high protein concentrations for direct neuronal injury—much greater than the actual quantity of the protein thought to be present in vivo. Furthermore, apoptotic neurons in HAD cannot co-localize with infected microglia, suggesting a multicellular etiology140. The activation of macrophages and astrocytes leads to an increase in proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and endothelial adhesion molecules. Glutamate, along with other excitatory amino acids, is also released by activated microglia141. When glutamate receptors are overstimulated, there is an excessive influx of calcium and the production of free radicals, including nitric oxide (NO), in neurones and astrocytes142. Prior research using primary mixed CNS cultures exposed to gp120 has revealed neuronal dendritic pruning, varicosities, vacuolation, and fragmentation143. Astrocytic enlargement and hyperplasia were present in conjunction with these neuronal damages, which is in line with neuropathological findings in HAD144. The importance of iNOS after gp120 exposure is partly derived from research demonstrating that iNOS inhibitors lessen a number of the negative effects of gp120. Elevated serum levels of cortisol in HIV-1 patients have been linked in numerous studies to the disease’s clinical progression145. It was shown that the secretion of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) by gp120 can stimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Nevertheless, exposure to gp120 was no longer sufficient to cause the production of CRF when l-NAME, a nonselective NOS inhibitor, was present146. Furthermore, it was observed that primary human astrocyte cultures exposure to gp120 had an upregulation of membrane CD23 protein. Aminoguanidine, an iNOS inhibitor, was able to inhibit the formation of NO and interleukin-1-beta (IL-1β) that was caused by this upregulation147. It has also been demonstrated that superoxide dismutase, glutamate receptor antagonists, and NOS inhibitors shield primary neuronal cultures from gp120148.

To conclude, several HIV-1 proteins, including Tat, Vpr, Nef, and gp120, have been shown to induce DNA damage and promote genomic instability. These proteins can induce oxidative stress, deplete glutathione levels, interfere with the host DNA damage response machinery, or directly damage DNA. These proteins can be released from infected cells and interact with uninfected bystander cells, suggesting that they may contribute to the pathogenesis of HIV-associated diseases beyond their direct role in viral pathogenesis.

Genotoxicity related to HIV-1 integration

HIV-1 integration, the process by which the proviral genomic DNA is inserted by viral integrase into the host cell’s genome, is a critical step in the viral life cycle149. Viral integration generates single-strand gaps and short overhangs at the ends of viral DNA, which activates the host cellular DNA damage response machinery150. A diverse range of host DNA repair mechanisms, including base and nucleotide excision, Fanconi anemia pathway, HR, and NHEJ, play crucial roles in HIV-1 integration and post-integrational DNA repair151,152,153,154,155,156. Interestingly, the DNA damage response can also restrict HIV-1 infection. The enzyme sterile alpha motif and HD domain-containing protein 1 (SAMHD1), a dNTP triphosphohydrolase, has been shown to restrict HIV-1 infection in resting CD4+ T cells, dendritic and myeloid cells by depleting dNTP pools, which are essential for viral reverse transcription and replication157,158,159. Besides depleting dNTP pools, SAMHD1 also has a direct role in maintaining genome integrity by promoting DNA end resection to facilitate double-strand break repair by HR160. DNA damage induced by certain agents, such as topoisomerase inhibitors and neocarzinostatin, enhances SAMHD1 activity in monocyte‐derived macrophages and further restricts HIV-1 infection161,162. Thus, the induction of double-strand DNA breaks in human monocyte-derived macrophages can contribute to their resistance to HIV-1 infection.

Insertional mutagenesis is not directly associated with oncogenesis in the context of HIV infection, since the majority of cancers in people living with HIV arise from cells that are not infected by HIV and do not contain proviral DNA163. Rare T-cell lymphomas bearing HIV proviral DNA have been documented in individuals living with HIV164,165,166. An exceptional case of B cell lymphoma (B cells are not susceptible to HIV infection) was reported to harbor an integrated HIV-1 provirus upstream of the STAT3 gene167. Despite this, the existing evidence suggests that insertion mutagenesis may contribute to the expansion and persistence of HIV-infected T cell clones168,169,170,171.

Genotoxicity of antiretroviral therapy

Over 30 antiretroviral drugs belonging to eight distinct mechanistic classes have received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HIV infection172. cART generally consists of a combination of at least three antiretroviral drugs from distinct classes, typically two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) combined with a third drug from one of three classes: HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), or HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) with a pharmacokinetic enhancer172. This synergistic combination effectively suppresses HIV replication, thereby reducing viral load and preventing the progression of HIV infection to AIDS.

Once they enter host cells, NRTIs undergo a series of phosphorylation reactions catalyzed by cellular kinases. These phosphorylated NRTIs then compete with cellular deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) for incorporation into the nascent viral DNA by reverse transcriptase. Upon incorporation, NRTIs act as chain terminators, preventing further DNA synthesis and effectively halting viral replication173. In vitro studies have demonstrated that NRTIs also have the potential to incorporate into nuclear and mitochondrial DNA and inhibit host DNA polymerases and induce DNA damage174,175,176,177. The potential of certain NRTIs to be incorporated by the mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ correlates with their mitochondrial toxicity174,176. NRTI-associated mitochondrial toxicity is a major adverse effect characterized by severe complications such as myopathy, peripheral neuropathy, hepatic failure, and lactic acidosis178. The incorporation of NRTIs into nuclear DNA was proposed to result in genotoxic and mutagenic effects: induction of genomic instability, increased mutation rates, chromosomal aberrations, micronuclei formation, and telomere shortening177,179. Zidovudine and stavudine were shown to be genotoxic in vivo177,180,181. Abacavir and emtricitabine increase the frequency of Burkitt’s lymphoma-associated translocation t(8;14) in CRISPR/Cas9-based cellular screening model182. Owing to their toxicity, older NRTIs, such as zidovudine (also known as azidothymidine), stavudine, and didanosine, are no longer recommended for clinical use172. Despite initial concerns about the genotoxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic potential of NRTIs, the evidence to date does not support their involvement in oncogenesis in people living with HIV25.

Studies on the genotoxicity of anti-HIV drugs are conducted in many laboratories. Studies of the widely used drugs, novel compounds, and combinations are on line. In experimental studies, genotoxic effects were reported for stavudine180, efavirenz, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate alone and in combinations183. DNA damage by azathymidine was observed both in experiments in cell cultures and mother–child pairs receiving this therapy177. Genotoxic effects of the drugs initially designed for anti-HIV therapy suggests investigation of anti-tumor effects of these compounds, studies were performed on HIV-1 inegrase inhibitor raltegravir184, protease inhibitor nelfinavir185 and other compounds.

Side effects of anti-HIV therapy can produce a negative impact on male fertility. Damage of spermatozoa DNA was observed in experiments on rats186 and confirmed in clinical studies. Significant fragmentation of spermatozoid DNA was observed in AIDS patients receiving active antiretroviral therapy compared to naïve HIV-infected men187.

Determining the precise impact of cART on cancer risk remains a challenging task due to the complex interplay of various HIV-related factors that contribute to carcinogenesis. The limited number of studies directly comparing the effectiveness of different antiretroviral drugs in cancer prevention further complicates the assessment of their individual roles in mitigating cancer risk.

Influenza viruses

The influenza virus is highly infectious and causes global epidemics and pandemics, with particular risks to vulnerable populations, including the elderly, children, pregnant women, and those with immunocompromised immune systems.

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) generated by the inflammatory response during severe influenza A infections play a critical role in the pathogenesis of the disease, inducing DNA lesions that can cause mutations and cell death. This inflammation-driven oxidative DNA damage frequently results in DNA strand breaks, which occur either through replication fork collapse or chemical reactions188. In response to DDR signals, which may include cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence, or apoptosis189. A common DDR process is the phosphorylation of γH2AX, which is triggered by DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) and ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase in response to DSBs. This formation of γH2AX foci around DSB sites renders it a valuable tool for the study of DNA damage caused by replicative stress during influenza infection190,191,192,193. The H1N1 virus has also been demonstrated to induce DNA damage in both in vitro and in vivo models, as evidenced by comet assays and γH2AX foci, in addition to elevated oxidative stress markers in the blood of infected patients194,195.

Chromosomal abnormalities are observed in both cultured cells and the leukocytes of infected patients. In vitro studies utilizing the comet assay on human leukocytes infected with the H3N2 strain A2/HK/68 demonstrated the presence of DNA damage within two hours, with a peak observed at 24 h196. Similarly, infection of HeLa cells with the H3N2 strain A/Udorn/317/72 resulted in DNA breaks, leading to apoptosis after 36 h197.

Furthermore, the DNA mismatch repair pathway is involved in the survival of infected cells. Moeed et al. demonstrated that caspase-activated DNase (CAD)-dependent DDR enhances immune responses by activating mitochondrial pro-inflammatory functions. The activation of CAD induces DNA damage responses, which involve kinase signaling, the NF-κB and cGAS/STING pathways, as well as neutrophil recruitment and cytokine production. In mice lacking CAD, reduced lung inflammation, increased viral load, and weight loss indicate that CAD plays a role in linking host defenses to cell death mechanisms198.

Ebola virus (EBOV)

The outbreak of the Ebola virus disease in 2014 resulted in a large number of human deaths. There are no direct indications on the host DNA damage by the virus, however bioinformatic analysis reveals the presence of ATM recognition motifs in all Ebola virus proteins, this suggests a potential role of DNA damage response pathways and ATM kinase in pathogenesis of the Ebola virus disease199. Moreover, EBOV VP24 matrix protein involved in virus budding and nucleocapsid assembly199,200 binds to Emerin, a nuclear membrane protein that interacts with lamins. Mutations or disruptions in lamin proteins are linked to many nuclear abnormalities, DNA damage, and diseases collectively termed laminopathies. EBOV VP24 disrupts these nuclear interactions by binding to emerin, lamin A, and lamin B, which results in the nuclear membrane rupture and the activation of the DNA damage response200,201,202,203,204,205,206. Furthermore, transcriptional modifications, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway activation, BAF displacement and downmodulation and alterations in nuclear morphology are linked to VP24 expression207. These alterations have the potential to harm DNA by activating the DDR mechanisms207.

Zika virus

The Zika virus (ZIKV) was initially identified in Africa in 1947. However, it was not until 2015 that it gained significant attention due to an outbreak in Brazil that was linked to congenital malformations and Guillain-Barré Syndrome208,209. ZIKV promotes endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and utilizes ER-derived vesicles for viral replication, thereby disrupting calcium ion (Ca²+) homeostasis between the ER and mitochondria. This disruption results in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which may lead to cellular damage210. Infection of human neural stem cells (hNSCs) by the African MR766 ZIKV strain results in elevated histone γH2AX phosphorylation, which is indicative of DNA damage. Interestingly, this phosphorylation occurs independently of the usual ATM/ATR-Chk1/Chk2 DNA damage signaling pathways. The distribution of γH2AX in MR766-infected is diffuse and nuclear, indicating extensive DNA damage211.

Picornaviridae

Single-stranded RNA viruses of the Picornaviridae family can infect both humans and animals. This group includes cardioviruses, such as the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), and enteroviruses, which encompass poliovirus, coxsackievirus, and rhinoviruses212.

Enterovirus A71 is a causative agent of hand, foot, and mouth disease in cattle and also represents a significant threat to human health, particularly among young children. Infection of children results in elevated γ-H2AX expression in lymphocytes, which serves as a marker for DNA double-strand breaks. Similarly, γ-H2AX forms complexes with viral proteins and the viral genome in newborn mice and is also detected in nucleated blood cells in infected sheep. The addition of antioxidants has been shown to reduce this effect, which suggests that oxidative stress may play a role in Enterovirus-induced DNA damage213,214,215.

The activation of DDR pathways, including kinases such as ATM, ATR, CHK1, CHK2, and aurora kinases, has been observed upon Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) infection. Similarly, kinases involved in cell cycle regulation, such as Greatwall kinase (GWL) and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) 1/2, are also affected by EMCV and CVB3, particularly during mitosis. The viruses have been observed to disrupt cell cycle regulation, with CVB3 causing cyclin D degradation and a potential interaction between the viral VP1 protein and CDK assemblies. Such disruptions are frequently associated with DNA damage and cell cycle arrest216,217,218,219,220,221.

The activation of the DDR and the presence of DNA damage have been documented in other enteroviruses, including EV-D68 and EV-A71. This indicates that the induction of DNA damage is a common event across picornavirus infections. This shared capacity is a significant aspect of the genotoxicity of picornaviruses, contributing to their ability to manipulate host cellular processes to facilitate viral replication and persistence222,223.

HTLV-1 and HTLV-2

Human T-lymphotropic viruses (HTLVs) are deltaretroviruses that possess a distinctive capacity to transform primary T cells in vivo and in vitro, despite the absence of a proto-oncogene in their genome. HTLV-1, the most prevalent of the HTLVs, has infected ~10 million individuals worldwide, predominantly in regions such as Africa, the Caribbean, and Japan. The virus can be transmitted via blood transfusion, sexual contact, or from mother to child during birth or breastfeeding. While a significant proportion of individuals remain asymptomatic, 3–5% eventually develop severe conditions, such as adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL), HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (HAM), or tropical spastic paraparesis (TSP), following a latency period spanning decades224,225.

HTLV-1 is a complex retrovirus that encodes typical retroviral genes (gag, pol, and env) and unique nonstructural proteins from the pX region. The aforementioned proteins include Tax and Rex, which are indispensable for viral replication, as well as p30, p12, p13, and HBZ, which facilitate host cell manipulation and viral survival. With regard to tropism, HTLV-1 displays a primary affinity for CD4+ T cells, whereas HTLV-2 exhibits a proclivity for CD8+ T cells. The elevated Tax-mediated transcription in CD4+ T cells substantiates HTLV-1’s proclivity for transforming these cells, although a considerable viral load is also maintained in CD8+ T cells. However, there is a paucity of knowledge regarding the in vivo pathogenicity and mechanisms of HTLV-2226,227,228,229.

The genotoxicity of HTLV-1 is strongly associated with the Tax and HBZ proteins. Tax activates the NF-κB pathway, which is critical for cell survival and inflammation, while HBZ engages with cellular transcription factors (e.g. E2F1, JunB, and CREB) that drive cell proliferation and transformation. Furthermore, HTLV-1 impairs immune signaling by activating the Jak/Stat pathway via Tax, thereby promoting cell survival and proliferation230,231.

The auxiliary protein p12, while not indispensable for viral replication or T-cell immortalization, provides further evidence of viral genotoxicity. It regulates T-cell proliferation by interacting with the 16 kDa subunit of the vacuolar ATPase complex, which is essential for lysosomal and endosomal function, and by binding to calcineurin, which releases calcium ions from the ER and activates the NFAT pathway. NFAT, a pivotal transcription factor, orchestrates calcium signaling with T-cell activation and amplifies cellular pathways that HTLV-1 exploits for viral survival and replication. Intriguingly, studies utilizing an infectious HTLV-1 molecular clone indicate that deleting p12 does not markedly influence viral replication, suggesting redundancy in viral proteins for sustaining the virus’s genotoxic effects232,233,234,235,236,237.

SARS-CoV-2

The global health crisis precipitated by the SARS-CoV-2 virus has resulted in millions of deaths and long-term consequences affecting multiple organ systems, including respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, and psychological impairments. Patients with severe forms of the disease exhibit elevated levels of DNA damage in their blood cells, particularly among younger individuals and those with more severe manifestations of the disease238,239. Oxidative stress represents a pivotal mechanism underlying this DNA damage, with elevated oxidative stress markers observed in patients. Furthermore, elevated expression of DNA damage response genes and γ-H2AX was observed in the cardiac tissue of SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals, even in the absence of direct viral infection240,241. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins can bind with Cu(II) ions, which results in the generation of excessive ROS within the mitochondria. This phenomenon may further contribute to the development of DNA damage. SARS-CoV-2 also degrades the DNA damage response kinase CHK1, leading to increased DNA damage, activation of pro-inflammatory pathways, and the onset of cellular senescence. DDR may, in turn, facilitate viral entry by enhancing ACE2 receptor expression, a process associated with telomere shortening and angiotensin II-induced ROS production. However, it is challenging to ascertain the virus’s direct contribution to DNA damage, particularly since many severely affected patients have pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, which are known to increase DNA damage independently of SARS-CoV-2 infection242,243,244,245,246,247.

DNA viruses

Epstein-Barr virus

Since its initial isolation in 1964, the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has grown to be a significant human tumor virus. EBV is associated with some malignancies, with an estimated 90% of the human population infected. Through a variety of epigenetic processes that it has evolved, the virus can impact its host and aid in the onset and spread of cancer248.

DDR pathway is activated during lytic EBV reactivation in response to a number of stimuli, including chemical inducers and human immunoglobulin G (IgG) cross-linking. However, it should be noted that the DDR response varies across different EBV-infected cell models. Proteins involved in the DDR play a pivotal role in the lytic replication of EBV DNA, with the ATM kinase being specifically localized to the viral replication compartment. In particular, the phosphorylated form of p53 (p53 serine 15), which depends on ATM, interacts with the BZLF1 protein during lytic DNA replication, indicating that p53 plays a regulatory role in EBV gene expression during this process249,250,251,252,253.

Overexpression of BZLF1 has the capacity to circumvent the ATM pathway in the induction of early lytic genes. In several cell lines, activation of the ATM pathway correlates with the peak of BMRF1 and BZLF1 expression. ATM knockdown in EBV-infected epithelial results in the loss of the viral replication compartment despite the widespread expression of early lytic proteins254,255,256.

Sp1 transcription factor accumulates at sites of DNA damage, where it is phosphorylated by ATM Sp1 is essential for the repair of double-strand breaks and is hyperphosphorylated by ATM during HSV-1 infection. Phosphorylated Sp1 plays a pivotal role in the establishment of the viral replication compartment during EBV lytic reactivation, binding to viral DNA replication proteins within this compartment256,257,258,259.

Parvoviridae

Human parvovirus B19 (B19V) is a human pathogen that belongs to the genus Erythroparvovirus of the Parvoviridae family, which is composed of a group of small DNA viruses with a linear single-stranded DNA genome. Due to a limited genetic resource, Parvoviruses use host cellular factors for efficient viral replication. Parvoviruses interact with the DNA damage machinery, which has a significant impact on the life cycle of the virus as well as the fate of infected cells. The B19V infection-induced DDR and cell cycle arrest at late S-phase are two key events that promote B19V replication. B19V mainly infects human erythroid progenitor cells and causes mild to severe hematological disorders in patients. It can also infect non-erythroid lineage cells such as kidney cells and myocardial endothelium260,261,262.

Infection of human dermal fibroblasts by parvovirus B19 is followed by induction of both single-strand and double-strand breaks as evidenced by comet assay and γH2AX staining263. The viral nonstructural protein, NS1 covalently binds to cellular DNA, induces single-strand nicks in it, then it is modified by PARP, an enzyme involved in the repair of single-strand DNA breaks. The DNA nick repair pathway initiated by poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase and the DNA repair pathways initiated by ATM/ATR are necessary for efficient apoptosis resulting from NS1 expression264. Thus infection by B19 might lead to genotoxic lesions.

KSHV(HHV-8)

Endothelial cells are susceptible to infection by Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus (KSHV), which can result in cellular transformation and the emergence of diseases such as Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and the plasmablastic variant of multicentric Castleman’s disease. Genotypic variations of KSHV have been observed across different geographical regions, with notable differences between sub-Saharan Africa and the Mediterranean. These genotype variations appear to be associated with specific disease manifestations265.

KSHV primarily persists in a latent, episomal form; however, similarly to EBV, it is capable of undergoing spontaneous lytic reactivation in a limited subset of cells, resulting in the production of new virions. Throughout both the latent and lytic phases, KSHV expresses genes that modulate the DDR by phosphorylating key proteins, including the tumor suppressor p53, and activating the ATM pathway5,9,266,267. The capacity of KSHV to establish and maintain latency is closely linked to its promotion of cell division and inhibition of apoptosis, which ultimately results in increased DNA damage and chromosomal abnormalities. During KSHV infection, several components of the DDR, including ATM, ATR, DNA-PKcs, and others, are transcriptionally downregulated. This allows the virus to evade apoptosis and control cell cycle checkpoints. This modulation of the DDR is of great importance for the facilitation of KSHV replication and persistence within the host9,268,269,270.

Conclusion and perspectives

Viruses, particularly those that persist and integrate into the host genome can cause significant genotoxic stress, leading to various biological consequences. During evolution, viruses developed ingenious mechanisms to exploit or manipulate the host’s genotoxic stress response for their benefit. To name just a few, HPV E6 and E7 degrade p53 and Rb, disabling the cell’s ability to repair DNA damage and control the cell cycle271; EBV latent membrane proteins LMP1 and LMP2 mimic growth factor signaling, promoting cell survival and proliferation despite DNA damage272.

It is evidently much more difficult to fight the consequences of genotoxic stress than with the stress itself. Some potential strategies include targeting viral oncoproteins that promote genotoxic stress and oncogenesis. For example, vaccines like the HPV vaccine prevent infection with high-risk HPV types, reducing the incidence of related cancers. In some cases, modulating the DNA damage response in virus-infected cells may help improve treatment outcomes, e.g. PARP inhibitors are being explored as potential therapies in HPV-associated cervical cancer273. Thus, understanding the mechanisms of virus-induced stress is crucial for comprehending how viral infections contribute to cancer, aging, and other diseases and for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Responses