Gestational diabetes exacerbates intrauterine microbial exposure induced intestinal microbiota change in offspring contributing to increased immune response

Introduction

The human microbiota encompasses a rich ecosystem that form a stable symbiotic relationship with the host and substantially impacts host’s metabolism and physiology [1]. In recent years, extensive attention has been focused on the microbiota development during pregnancy and early life, as disruptions of the microbiome have been linked to chronic diseases and mental disorders in the next generation [2,3,4]. Contrary to the past belief that the fetus remains germ-free during gestation, some studies have reported traces of microbes in human placental and fetal samples [5,6,7], emphasizing the potential for maternal transmission of microbes. Fetal exposure to maternally derived microbial components was also found which associated with early-life immune system development. Lipopolysaccharide(LPS), a typical proinflammatory molecule produced by gram-negative bacteria in the intestines, can translocate to the maternal bloodstream from a leaky gut and adversely affect pregnancy outcomes such as impairing spermatogenesis and developing ASD-like behavior in the next generation [8, 9].

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is prevalent worldwide. Its high prevalence, along with associated transgenerational consequences and serious complications, necessitates new approaches to understand its pathophysiology [10, 11]. It has been suggested that GDM significantly alters the composition of the intestinal microbiota in offspring, potentially leading to health risks such as obesity, insulin resistance, and even diabetes in the next generation [12,13,14]. However, the association between GDM, microbial signaling in the embryonic stage, postpartum microbiota construction, and early-life immune responses remains unclear.

In this study, using samples from GDM women and animal model, we first aimed to confirm whether GDM led to elevated intrauterine microbial signaling after gestational microbial exposure. The presence of intestinal microbes in offspring was also examined, with further study on innate and adaptive immune responses. Finally, whether maternal GDM affects the intestinal microbial composition and colony stability of offspring were examined. For animal models, sterile cesarean section delivery of fetuses and fostering by normal female mice were conducted to minimize postnatal microbial exposure.

Methods

Subject recruitment

Pregnant women and neonates were recruited at The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. The study was approved by the Medicine Ethics Committee at The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. All participants provided written informed consent for themselves and the neonates. Pregnant women with GDM were diagnosed by specialized doctors according to the results of oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and were recruited as a case group. The diagnosis of GDM is based on the GDM diagnostic guidelines formulated by the World Health Organization. The diagnosis of GDM was performed by the 75 g OGTT at 24–28th gestational weeks with at least one of the following criteria: fasting ≥ 5.1 mmol/L, 1 h ≥ 10.0 mmol/L, or 2 h ≥ 8.5 mmol/L [15, 16]. In this study, subjects with pre-existing diabetes, pre-existing metabolic diseases, antibiotics usage within 3 months, alcohol or substance abuse, periodontitis, bacterial vaginosis, and chronic diseases requiring medication were excluded. Women with normal pregnancies were matched for maternal age, BMI and medical history. Placenta and umbilical cord blood were collected immediately after cesarean section to detect immune related indicators. Patient sample and data were collected under approval by the Medicine Ethics Committee at The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (2020–565). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Animals and diet

C57BL/6 J mice (6 weeks old) were purchased from the animal core facility of Chongqing Medical University. Mice were housed in a stable facility with 12 h light/12 h dark cycles at 25 °C. All mice were stabilized for a week before initiating any experimental procedures. Before assigning the animals, it is crucial to ensure that the mice are uniform in terms of litter, gender, and age. Then, the mice are to be paired based on weight, forming a basic group of four mice with similar weights. Subsequently, the animals within each group will be randomly assigned to either the experimental or control groups, ensuring that the groups have similar litter, gender, age, and weight composition. Throughout the subsequent experiments, the animals will be cared for by personnel who are unaware of the mice’s grouping, thus guaranteeing uniform care across all groups. A GDM mice model was established by feeding mice with a high-fat diet (HFD, 60% kcal, D12492, Research Diet, USA) for 4 weeks before pregnancy and was maintained with HFD until delivery. Normal pregnant (CON) mice were fed a normal chow diet throughout pregnancy. Female mice were mated with male mice overnight at a proportion of 2:1 per cage. Pregnancy was determined by the presence of vaginal plugs the next morning, which was identified as gestational day 0. The next day, the mice in GDM group were intraperitoneally injected with STZ (25 mg/kg, dissolved in 0.1 mmol/L citrate buffer, pH 4.2–4.5, S0130, Sigma–Aldrich, USA), followed by 3 injections every 24 h. The control mice were injected with a similar amount of citrate buffer. Random blood glucose was tested from the tail by glucometer (ACCU-CHEK Guide, Roche, USA) 72 h after the first STZ injection. Mice with random blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L were regarded as qualified GDM mice. The GDM mice were then randomly divided into two groups: the GDM- group and the labelled bacteria group (GDM + ). The purpose is to clarify the colonization of microorganisms from different sources in their offspring under different maternal health conditions [17]. The Control mice also were then randomly divided into two groups: the Control group (CON-) and the labelled bacteria group (CON + ).

On gestational day 1, the CON+ and GDM+ group were fed 0.1 ml of preparation with 109 colony forming unit (CFU) / ml of labeled E. coli daily until gestational day 19, the CON- and GDM- group were fed same volume of sterile PBS [18]. On gestational day 21, all mice underwent cesarean section in a sterile environment, and the pups were nursed by normal female mice. Placenta were collected immediately after cesarean section to detect immune related indicators. All the animal experiments conformed to guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals published by Institutional Animal Ethical Committee. The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chongqing Medical University. all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Bacteria preparation

Lactobacillus (GMCC0460.2) were first grown and expanded in MRS broth at 37 °C and 5% CO2, and resuspended in modified Hank’s balanced saline solution (HBSS) supplemented with 0.04 M MgSO4, 0.03 M MnSO4, 1.15 M K2PO4, 0.36 M sodium acetate, 0.88 M ammonium citrate, 10% polysorbate and 20% dextrose. Bacteria then were propagated overnight at 37 °C, 5% CO2 under non-agitating conditions to 2 × 109 cfu/ml.

E. coli Nissle 1917 were engineered to eGFP labeled and confer resistance to Kanamycin. Before oral administrations, E.coli were grown for 6 h in LB broth supplemented with Kanamycin (50 µg/mL) at 37 °C with shaking. This culture was diluted 1:100 in LB broth without antibiotics and cultured overnight at 37 °C with shaking. Bacterial pellets from this overnight culture were diluted in sterile PBS to the concentration of 109 cfu/ml [19].

Fostering

On embryonic day 19, mice were anaesthetized and euthanized via cervical dislocation. The pups were delivered via sterile c-section, moved to a preheated, sterile, damp gauze and carefully monitored for onset of regular breathing. Next, mice were brought into contact with bedding from the cage from the dam that they would be fostered to the age-matched pups of the foster mother were marked via clipping of the tail to distinguish them from the fostered pups that were placed in the same cage. Cages were left undisturbed for at least 2 days to facilitate acceptance of foster pups. Pups were weaned at 3 weeks of age. Some pups are sacrificed to collect intestinal immune cells after weaning. The remaining pups were treated by oral gavage with 109 cfu of E. coli or Lactobacillus in 100 µl/day of PBS or 100 µl/day of PBS as negative control within three days.

Sample preparations and DNA extractions

Fecal samples were collected from colons at sacrifice and stored at −20 °C. For bacterial DNA extractions, we included an additional enzymatic lysis procedure before using the Powersoil Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories). Briefly, 50 μL lysozyme, 6 μL mutanolysin, and 3 μL lysostaphin were added to 100 μL aliquot of cell suspension followed by incubation for 1 h at 37 °C. The lysate was then subjected to further DNA isolation and purification using the Powersoil DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories) as the manufacturer’s instructions. The final DNA concentration was determined by the Quanti-It Picogreen dsDNA HS assay kit (Invitrogen, UK).

Oral glucose tolerance tests

Following fasting (12 h deprivation of diet: 8:00 p.m. to 8:00 a.m.), these mice were intraperitoneally injected with a solution of D-glucose (2 g/kg body weight). We obtained blood samples from the tail vein of mice at 0 minutes (just before glucose load), as well as 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after glucose administration. Blood glucose levels were measured using the glucometer, followed by the calculation of the area under curve (AUC).

Isolation of CD4+ T Cell

Disrupt spleen in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Remove clumps and debris by passing the cell suspension through a 70-μm mesh nylon strainer. Centrifuge at 300 g for 10 min and resuspend in medium (PBS containing 2% FBS and 1 mM EDTA). CD4+ T Cells were subsequently isolated using the Mouse CD4 Positive Selection Kit (Beaver Bio Ltd).

Isolation of mononuclear cells

Disrupt spleen in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Remove clumps and debris by passing the cell suspension through a 70-μm mesh nylon strainer. Adding the same amount of separation solution as the organ tissue single-cell suspension (P6340, Solarbio). Carefully aspirate the single-cell suspension and add it to the surface of the separation solution. Centrifuge at 500 g for 25 min. Carefully pipet the second layer of mononuclear cells into another sterile 15 mL centrifuge tube, add 10 ml of cell washing solution to the centrifuge tube to wash, and then centrifuge at 250 g for 10 min. Discard the supernatant, resuspend the cells in 5 mL of PBS or cell washing solution, and centrifuge at 250 g for 10 min.

Monocytes differentiate into dendritic cells

Isolating mononuclear cells from peripheral blood by Blood Mononuclear Cell Separation Kit (P6340, Solarbio, China), which were induced in vitro by colony stimulating factor (P00184, Solarbio, China) and recombinant interleukin 4 (P01498, Solarbio, China). Then on day 5, 100 ng/mL of tumor necrosis factor-α was added for 2 days to induce maturation.

Co-culture of T cells with DC

Add the desired stimuli such as heat-killed E. coli or Lactobacillus to plated DCs, and incubator for 24 h. DC were gently washed with sterile PBS and T cells were added to each well in 1:10 ratio of DC:T cells, and incubated for 4 days in T cell media. Post 4 days culture, T cells were harvested to detect cytokines [20].

Determination of LPS and TNF-α levels

Cord blood was collected immediately after delivery. Serum was obtained by centrifugation (3000 g, 15 mins, 4 °C) for measurement of LPS (CSB-E09945h; CUSABIO). Analyses were performed in duplicate, according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The detection range was 6.25pg/mL- 400 pg/mL. If the measurement was lower than the lowest limit of detection, the value was substituted with the lowest limit of detection.

Cord blood was collected immediately after delivery. Serum were obtained by centrifugation (3000 g, 15 mins, 4 °C) for measurement of TNF-α (CSB-E04740h; CUSABIO). Analyses were performed in duplicate, according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The detection range was 7.8–500 pg/mL. If the measurement was lower than the lowest limit of detection, the value was substituted with the lowest limit of detection.

Western blot

Intestinal tissue was used for Western blot analysis. Briefly, intact aortic rings were isolated from the different treated offspring. The rings were then homogenized in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Homogenates were ultrasonicated for 15 s, and then centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 10,000 g. Supernatants were collected, and protein concentration was determined. Samples with equal protein were loaded and separated on 10% PAGE-SDS. The membranes were incubated with primary antibody (TLR4 Proteintech 66350, TLR5 Proteintech 66570, Il-22 abcam ab133545, IL-23 abcam ab189300), followed by a secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. Proteins were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents, and blots were exposed to Hyperfilm (Advansta, USA) and FUSION FX (Vilber Lourmat, France). The band intensity was quantified using FusionCapt Advance FX5 software (Vilber Lourmat, France).

16S rRNA gene sequencing

The faeces of the pups are collected after weaning. 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed using the extracted metagenomic DNA. The hypervariable V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified via PCR in two steps: the first step barcoded the samples and the second added Illumina paired-end sequencing adapters. The resulting PCR amplicons were purified using the Qiagen 96-well purification kit (Qiagen, Germany), the amplicon concentration was determined using the Quanti-It dsDNA BR assay (Invitrogen, UK), and 50 ng from each reaction was pooled into a single tube. Pooled DNA was run on a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized, and the 330-bp band was carefully cut out of the gel and purified using a gel purification kit (Qiagen, CA). The final DNA concentration was determined and the library sequenced from both ends at The Centre for Applied Genomics at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada, on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform (100 base paired-end chemistry). Appropriate positive and negative controls were run alongside each library to confirm lack of contamination and accuracy of the analysis pipeline.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 8 (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., La Jolla, California, USA). Among-group differences were analyzed using the two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Result

Increased umbilical cord blood LPS content in GDM women

We collected umbilical cord blood from women with GDM and normal pregnancies. The detailed characteristics of the included study subjects are shown in Table 1. Compared with the non-GDM group, the GDM group showed a higher level of LPS, a proinflammatory molecule produced by Gram-negative bacteria. This result is consistent with a previous study [21]. The increased LPS level in the umbilical cord blood suggests a potentially increased opportunity for microbial exposure in the early life of fetuses carried by GDM mothers.

Increased presence of intestinal microbes in offspring of GDM mice after gestational microbial exposure

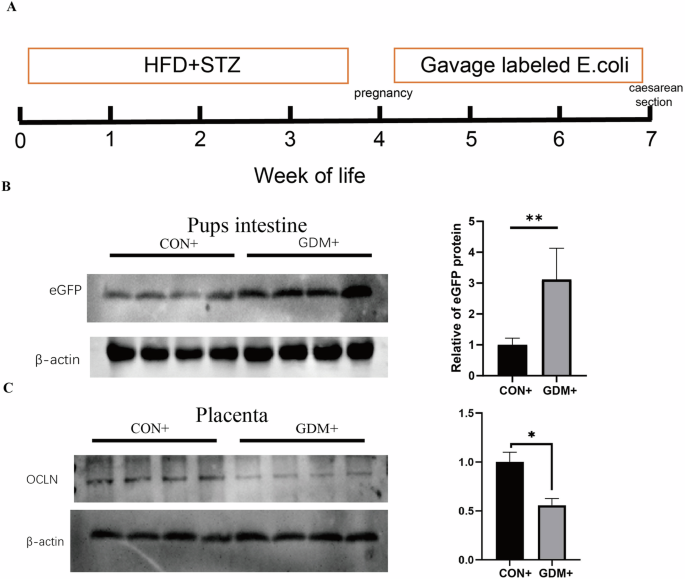

Next, kanamycin-resistant E. coli labeled with Green fluorescent protein (GFP) was administrated to pregnant mice to investigate whether the presence of microbes was increased in fetus after maternal microbiome exposure of GDM mice. GFP is not naturally existed in mice, so its detection signals the presence of E.coli. The experimental process and the experimental groups were outlined in Fig. 1A. Microbial cultivation was utilized to detect the presence of labeled E. coli in fetal mice. We grounded the intestines of the fetal mice in a sterile environment for further microbial cultivation and GFP detection. Out of a total of 20 mice in the GDM group, 4 mice were found to have a positive culture of kanamycin-resistant E. coli, resulting in a positive rate of 20% (Supplemental Fig. 1). Western blot analysis confirmed that the concentration of GFP was also higher in the intestines of GDM fetal mice than in the control group (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we observed that the placental barrier marker OCLN was downregulated in GDM mice, indicating compromised placental barrier integrity from gestational diabetic pregnancies (Fig. 1C).

A The experiment processes. B Western blotting results and quantitative analysis for pubs intestinal green fluorescent protein. C Western blotting results and quantitative analysis for placental barrier. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, GDM vs CON.

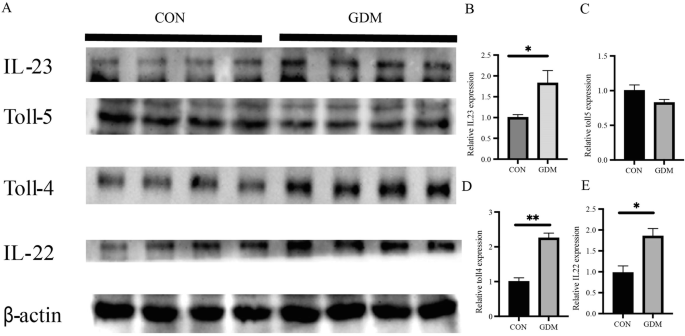

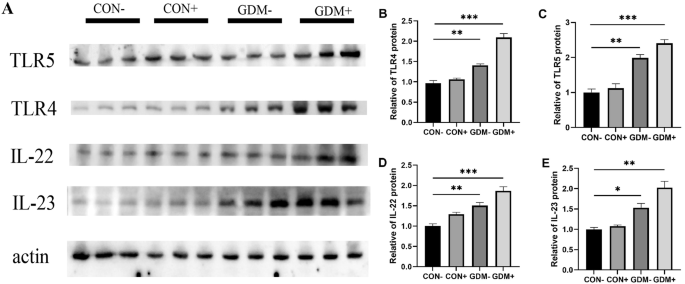

GDM affects the intrauterine innate immunity

Intrauterine antigen exposure is critical for immune system development, and LPS can activate the innate immune system, exhibiting the most potent immunostimulating activity of the TLR ligands. We next detected innate immune markers produced through LPS activation in human placental tissue. It was found that in GDM women, the expression of toll-like receptors 4 (TLR4) in the placenta, and proinflammatory mediators IL-22, IL-23 in the downstream signaling pathways of toll-like receptors were all significantly increased, and no significant difference was found with toll-like receptors 5 (TLR5) expression (Fig. 2). Subsequently, we found similar pattern of changes with these indicators in the placenta of GDM- and GDM+ mice, that after gestational E. coli exposure, the innate immune markers TLR4, TLR5, IL-22 and IL-23 were significantly increased as compared to the CON- and CON+ mice (Fig. 3). Compared to the GDM- group, the GDM+ group exhibits a more pronounced activation of the TLR signaling pathway, possibly due to a stronger immunostimulatory effect of exogenous microbial intervention. Since toll-like receptors play an important role in the recognition of microbe, this may indicate that maternal GDM increased the risk of placental microbial signal exposures that activate different immune responses.

A Images of Western blotting for immune markers from human placental tissue. B Quantitative analysis of IL-23 western blot results. C Quantitative analysis of Toll-5 western blot results. D Quantitative analysis of Toll-4 western blot results. E Quantitative analysis of IL-22 western blot results. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

A Images of Western blotting for immune markers from mice placental tissue. B Quantitative analysis of TLR5 western blot results. C Quantitative analysis of TLR4 western blot results. D Quantitative analysis of IL-22 western blot results. E Quantitative analysis of IL-23 western blot results.; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001,GDM− vs CON−, GDM+ vs CON−.

GDM affects the intrauterine adaptive immunity

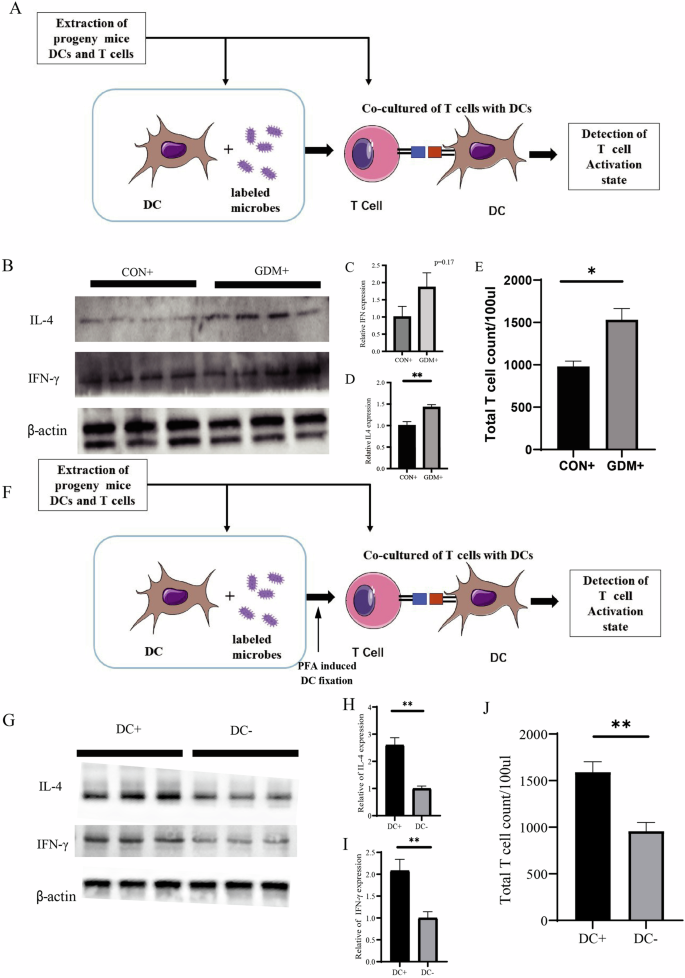

Since the adaptive immune response is more specific to an invading pathogen, we further sought to investigate whether maternal exposure to pathogens during gestation can activate adaptive immunity in offspring. To determine whether the T cells’ recall response by dendritic cells (DC) presenting E. coli-derived antigens in the offspring can be affected by maternal GDM, we conducted co-culture experiments to verify the responsiveness of memory T cells to microbial signals. The experimental process and the experimental groups were outlined in Fig. 4A. We isolated T cells from the intestines of pups to assess their immunological memory of T cells to labeled E. coli. The immune cytokines secreted by memory T cells, such as IL-4 and IFN-γ, were significantly increased in pups from the GDM+ group compared with the CON+ group (Fig. 4B–D). Furthermore, antigen-exposed T cells in the offspring of GDM+ also exhibited a more significant expansion compared to the control (Fig. 4E). To illustrate the role of DC cells in activating memory T cells upon recurrent encounters with identical signal, we treated DCs with paraformaldehyde (PFA) to fix them (Fig. 4F). Our results indicated that the cohort with intact DC function (DC + ) successfully activated T cells, whereas the cohort with impaired DC function (DC-) displayed a marked reduction in T cell activation.

A The experiment processes. B–D Western blotting results and quantitative analysis for IL-4 and IFN-γ expressed by T cells. E T cell count after co-culture. F The experimental processes. G–I Western blotting results and quantitative analysis for IL-4 and IFN-γ expressed by T cells. J T cell count after co-culture. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, GDM vs CON.

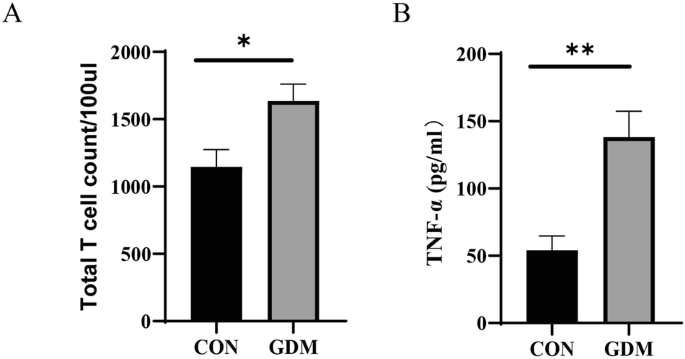

Subsequently, we collected cord blood from GDM women under sterile conditions and isolated T lymphocytes from the cord blood. We also conducted co-culture experiments to verify the responsiveness of memory T cells to microbial signals in humans. We observed similar changes, including a higher T cell count and increased IFN-γ levels in the cord blood from GDM mothers (Fig. 5A, B). The activation of T cells and their response to specific microbes may suggest that maternal GDM increases microbial exposure induced adaptive immunity in utero and shapes the early immune memory of intestinal microbes.

A T cell count after co-culture. B Levels of TNF released in the culture supernatant of T cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, GDM vs CON.

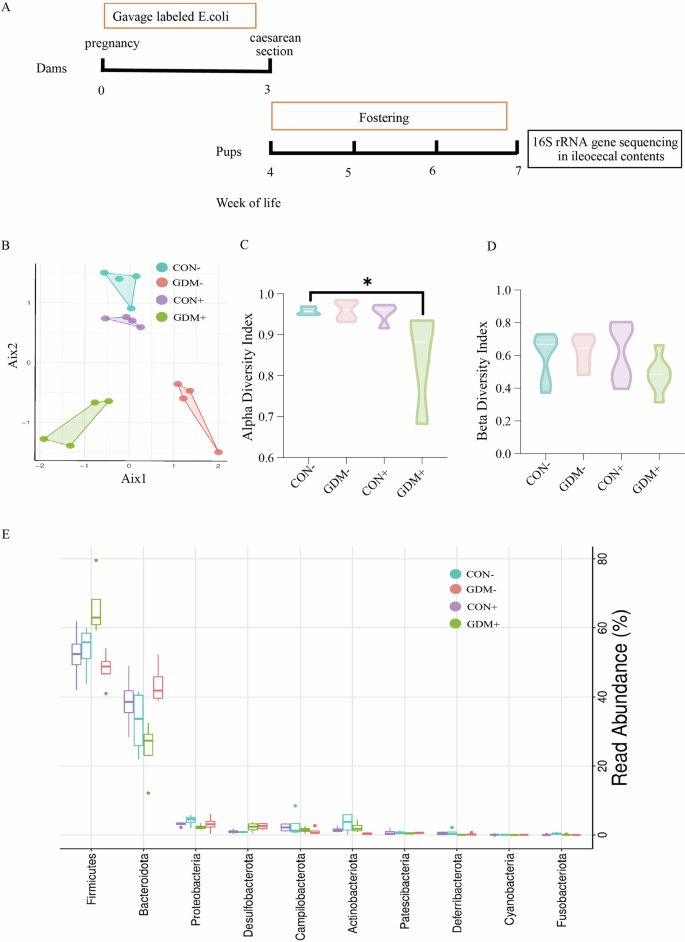

Maternal GDM affects intestinal microbial composition of offspring following early life exposure to microbes

To further elucidate the features of neonatal gut microbiota colonization, we utilized 16S rRNA gene sequencing to characterize the composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota of pups from four groups: CON-, GDM, CON + , and GDM + . Canonical Correspondence Analysis and comparison of the abundance of single OTUs revealed significant differences among these four groups (Fig. 6B). The alpha diversity was notably lower in the progeny of the GDM+ group (Fig. 6C), indicating a decrease in microbiome diversity. Notably, the beta diversity of the four groups showed no significant difference (Fig. 6D). Further analysis revealed that the progeny of the GDM+ group exhibited a decreased abundance of OTUs classified as the Bacteroides phylum compared to the CON+ group, while the abundance of OTUs classified as Firmicutes increased (Fig. 6E). Consequently, an increased ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes was observed in the GDM+ group. However, the CON+ group showed decreased Firmicutes and increased Bacteroidetes compared with the CON- group. These changes were less pronounced in the non-GDM groups. Overall, the results suggest that maternal GDM not only influences the diversity and abundance of gut microbial colonization in offspring but may also impact the resilience of the gut microbiota in offspring after early-life microbial exposure.

A The experiment processes. B Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) of the intestinal flora in the four groups mice. C, D The alpha and beta diversity of the intestinal flora in the four groups mice. E Most significantly altered intestinal microbial in four groups of mice.

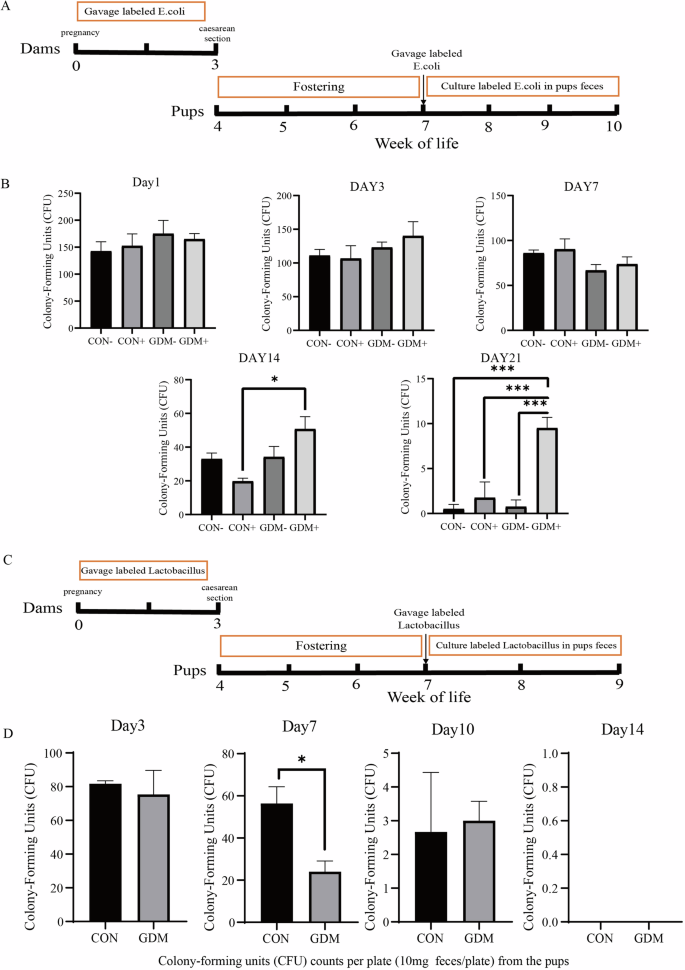

Maternal GDM affects the stability of intestinal microbial colonization in offspring

As the immune response is closely related to microbial colonization [22, 23], We sought to determine whether changes in immune memory in the uterus lead to changes in the affinity of offspring to specific microorganisms. Consequently, our subsequent examination aimed to assess whether maternal GDM affects the microbiome stability of the offspring and thus modulates microbial diversity and abundance. The experimental process and the experimental groups were outlined in Fig. 7A. As E. coli represents one of the most common species in the initial fecal material of newborns [24], we fed the offspring with labeled E. coli for three days and observed different colonization stability between the groups (Fig. 7B). The colony counts of labeled E. coli detected in the feces of the four groups showed no significant difference from the first to the third day of feeding. Even on the 7th day with a decline in E. coli colonies in all four groups, there was still no significant difference. However, by the 14th day, E. coli colonies in the pups’ feces from the GDM+ group was statistically higher than that in the CON+ group, and it remained the highest among all the experimental groups on the 21st day. These results indicated that although the number of E. coli colonies isolated from the pups’ feces decreased without exogenous supplementation, they exhibited stronger colonization stability with maternal GDM. However, no changes in body weight and glucose tolerance between the groups were observed (Supplementary Figure 2).

A The experiment processes. B Detection of labeled E.coli in feces of the offspring at different time points after intervention. C The experiment processes. D Detection of labeled lactobacillus in feces of the offspring at different time points after intervention. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, GDM vs CON.

On the other hand, when Lactobacillus, a typical probiotic and representative species of the phylum Firmicutes, was administered to the offspring for three days, neonates from GDM mothers showed a faster decrease of the labeled Lactobacillus colonies after the feeding was stopped, resulting in a much lower colony count than the control group on the 7th day, although both groups exhibited very low colony counts on the 10th day (Fig. 7C). Overall, these results suggest that maternal GDM has a more sustained effect on stabilizing the gut E. coli microbial flora of the newborn, while interfering with the colonization of gut probiotics, resulting in a much lower colony count.

Discussion

GDM is closely associated with the neonatal gut microbiota, underscoring the significance of maternal factors in metabolism and immunity [14]. While the effect of the postnatal environment and nursing on the microbiota has been well-documented [25, 26], less is known about the impact of GDM on intrauterine microbial exposure and the consequences of shaping the immune response during the embryonic stages. In this study, using exogenous microbial intervention in a GDM mouse model and minimizing the influence of delivery mode through C-section, we demonstrated that maternal GDM decreased the diversity of gut microbial colonization, with an increased ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes in offspring. This change in microbiome composition was likely related to a more sustained effect of GDM on stabilizing E. coli microbial flora while interfering with Lactobacillus colonization. Together with compromised placental barrier integrity, this increased the fetus’s susceptibility to gestational microbial exposure, thereby triggering intrauterine innate immunity and establishing a stronger adaptive immunity towards specific intestinal microbiota.

The conventional belief in early life colonization posits that the fetus develops in a sterile in utero environment and becomes colonized with microbes after birth through processes such as vaginal delivery, breastfeeding, and other environmental exposures [27, 28]. However, recent studies showed that the mother can directly pass on gut microbes to her offspring during pregnancy, while some studies concluded that the bacterial DNA found in the placenta was related to environmental pollution. Thus, the current concepts about the existence of fetal microbiota is still a field full of controversy [29,30,31,32,33,34]. In our study, we focused pregnancy on a specific pathological condition-GDM and its association with the establishment of bacterial colonizing in offspring after childbirth and shaping of the immunological response. Our data suggest that the murine fetus is exposed to maternal intestinal bacteria, while GDM increased the risk of such an exposure. With higher level of LPS found in placenta of GDM patients, we speculate an altered uteroplacental function resulting from this disease. Subsequent animal studies showed decreased expression of occludin in placenta from GDM mothers, an integral membrane protein required for cytokine-induced regulation of the tight junction paracellular permeability barrier including the blood placenta barrier [35]. As a result, increased access of pathogens from maternal blood into, and persistence in, the fetal environment was observed following mothers’ exposure to exogenous bacterial intervention.

In addition to compromised placental function, GDM also associates with mechanisms that confer resilience to the stable states of the gut microbiota after early-life microbial exposure. As is known, the gut microbiota is often highly resilient to perturbations, allowing the host to maintain key species for extended periods [36]. Previous studies have revealed that perturbations such as diet and antibiotic exposure have impacts on the gut ecosystem [37,38,39]. In our study, following early-life E. coli exposure, maternal GDM was found to promote prolonged residence of E.coli in the gut when offspring were orally administered with this bacterium. Conversely, GDM was associated with a rapid decrease in colonization of Lactobacillus when probiotic supplementation to progeny was stopped. Thus, GDM possibly decreases resilience to unhealthy bacterial perturbation and increases resilience to the colonization of probiotics.

This finding also adds to our understanding of the Lactobacillus supplementation during gestational diabetes. Past research had mostly focused on the effect of improving maternal and infant health [40, 41], while little is known about the changes in bacterial colonization after supplementation. Moreover, these findings also provide explanations for the increased presence of detected intestinal microbes in neonates from GDM mice after gestational microbial exposure, and the increased LPS content in umbilical cord blood from GDM women.

Previous studies have demonstrated long-term consequences of antibiotic-perturbed maternal microbiota on offspring’s susceptibility to metabolic diseases, involving changes in the fetal immune system [25, 42, 43]. Consistent with recent studies suggesting a long-term effect on offspring immune system development through the maternal disease-gut microbiome-immunity axis [44], the data we present here demonstrate that GDM can significantly influence the composition of the intestinal microbiota of the offspring, consequently shaping the innate and adaptive immunity for the next generation. Notably, using the same bacterial strains as mothers were exposed to during gestation induced stronger activation of memory T cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes of infants from GDM mothers. Previous studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between changes in immune cells and the presence of different gut microbiota. The immune system interacts with intestine microorganisms, and not only do gut microbiota influence host immunity, but the immune system also influences the composition of gut microbiota [44,45,46,47]. Additionally, our research has revealed the early effects of intrauterine microbial exposure on the immune system, establishing immune memory triggered by maternal microbiota from early life. Overall, our study highlights the impact of GDM on offspring’s microbiota development after early life exposure to pathogens, which may be linked to the future risk of disease development.

Our study utilized cesarean section under a sterile environment and fostered the progeny with healthy maternal mice in an effort to minimize the disturbance of early intestinal microbiota caused by delivery and breastfeeding. However, there are several limitations that should be addressed in future studies. First, we have not been able to clarify the specific mechanism by which GDM triggers a stronger immune response in offspring after intestinal microbial exposure during pregnancy. Second, changes in metabolic phenotype were not observed in the offspring of GDM mice, as we only examined body weight and glucose tolerance as indicators for metabolic syndrome within limited time. Therefore, we have not been able to determine whether GDM-induced immune responses are linked to the future risk of developing metabolic diseases. Future studies are warranted to include a more comprehensive metabolic profile with long-term observation. Third, the disparity between animal models and human subjects is an issue that warrants attention. In our study, animal models feeding bacterium are utilized to investigate the impact of intrauterine microbial exposure on the colonization of offspring gut microbiota. However, the GDM patients did not consume exogenous E.coli during pregnancy out of ethical concern, the findings from animal studies may not be directly applicable to human subjects. Therefore, further clinical researches are needed which should include subjects under specific conditions such as GDM women with a history of E.coli infection during pregnancy.

Conclusion

Our study revealed a significant association of gestational diabetes with intrauterine microbial exposure, changes in neonatal microbiota, as well as the activation of immune responses. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the effects of gestational diabetes on exacerbating the consequences of early-life pathogen exposure. Further studies are warranted to explore the implications of these findings for infant’s health later in life.

Responses