Gestational weight trajectory and early offspring growth differed by gestational diabetes: a population-based cohort study

Introduction

The importance of early childhood growth and development cannot be underestimated. Early growth rate not only serves as crucial indicators for assessing children’s health status but also are closely associated with the risk chronic diseases later. For example, studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between excessive gain in BMI in early childhood and the presence of cardiovascular risk factors or diabetes in adulthood [1,2,3]. Therefore, it is essential to explore the factors influencing early childhood growth and development.

Pregnancy is a critical period for shaping offspring health. In recent times, inappropriate gestational weight gain (GWG) has attracted mounting concerns as a contributory factor for adverse outcome [4]. GWG, as a potential modifiable indicator for fetal nutritional support, is now recommended to routinely assessment as part of prenatal care. For optimizing maternal and child health outcomes, some institutions have provided guidelines [5,6,7], with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guideline in 2009 most widely accepted. The guideline provides the recommended rate of GWG and total GWG according to the pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) [5].

Currently, aside from birth outcomes, accumulating evidence suggests that total GWG above the IOM recommendations also increases the risk of offspring developing high BMI z-score trajectories [8] or becoming overweight/obese [9, 10]. However, some research indicated it may be problematic to link total GWG with adverse offspring health outcomes because total GWG is closely related to gestational age, potentially leading to spurious associations between inappropriate GWG and adverse outcomes of offspring [11]. Although, some previous studies have assessed GWG in relation to children’s longer-term growth and development by specific trimester [12,13,14] or gestational age [15], these evidences assessed each trimester independently, rather than assessing the entire shape of the weight change. However, leveraging methods like latent class analysis to focus on the pattern or trajectory of GWG could provide stronger clinical utility as a prospective monitoring tool for clinicians [16, 17]. Despite the utility of this method, only a few studies thus far have employed it to assess the relation between GWG and development of offspring, such as the weight [18], overweight/obesity status [19] and body composition [16].

Additionally, as the most common medical complication, the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has been shown to strongly influence GWG management [20], suggesting that weight progression varied between individuals with and without GDM. However, in pregnancies characterized by GDM, the effects of pattern and timing of GWG on perinatal and offspring outcomes remain unclear. Modeling the GWG pattern with methods like latent class analysis would better to comprehensively capture GWG dynamics in pregnancies with GDM, helping to differentiate the effects and progression of GWG between individuals with and without GDM. To our knowledge, there seems to be no studies have focused on modeling GWG trajectory and examined the associations between GWG trajectory and offspring growth, based on the status of GDM.

To address these gaps and in-depth supplement in the literature, we aim to model the GWG trajectory, and investigate the effects of GWG trajectories on the growth of offspring before 36 months. Meanwhile, we modeled the trajectory based on GDM status and assessed whether there are differences in the association between GWG trajectory and offspring growth among individuals with and without GDM.

Methods

Data source and participants

Data were extracted from a comprehensive Electronic Medical Record System (EMRS) of Zhoushan Maternal and Child Care Hospital, Zhejiang province, China between October 2011 and October 2022. The EMRS is a municipal system containing information of all pregnant women and newborn health care in Zhoushan city after 2011, as previously described [21, 22].

Participants who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled, including: (1) maternal age between 18 and 50 years old; (2) live singleton pregnancy; (3) first antenatal care visit before 14 weeks of gestation; (4) at least 3 prenatal weight measurements recorded throughout pregnancy; (5) at least 2 anthropometric measurements of offspring (i.e., height and weight) taken between the ages of 1 and 36 months. Additionally, pregnant women with pre-existing diabetes, preterm birth, and those whose pregnancies resulted from assisted reproductive technology were excluded, due to their potential effects on estimating GWG patterns and offspring development. Ultimately, 2083 mother-child pairs were excluded and the final analysis comprised 13,424 pairs. We further conducted the sensitivity analysis, and found that there were no significant differences in socio-demographic characteristics between the initial and final samples, except for gravidity (Table S1). Informed consent was obtained from subjects involved in the study. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (No. 2011-1-002).

The definition of gestational diabetes mellitus

In China, pregnant women routinely undergo screening for GDM through a 75-g Oral Glucose Tolerance Test during the 24–28 gestational weeks. The diagnosis of GDM, according to the International Association for Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) criteria, is determined if any of the following thresholds were exceeded: fasting glucose levels ≥ 5.1 mmol/L, 1-h post-glucose ≥ 10.0 mmol/L, or 2-h post-glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/L.

Assessment of GWG and gestational weight gain trajectory

The weight in kilograms (kg) of pregnant women was measured by qualified staff at each antenatal examination. Pre-pregnancy BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2) at the first antenatal care visit, and were classified as: underweight/normal weight (BMI < 24.0 kg/m2) or overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 24.0 kg/m2), according to the BMI standards for Chinese adults [23].

In this study, maternal GWG in the 2nd and 3rd trimester (from 14 weeks to delivery) was defined as the difference in maternal weight between each antenatal examination and the 13th week. For pregnant women without weight measurements at the 13th week, a weight measurement taken within the previous a month was used as a substitute. The maternal GWG rate (kg/week) was defined as the mean weekly weight gain. Subsequently, GWG was classified as insufficient, adequate, or excessive, according to the 2009 IOM guideline [5].

The GWG trajectory of 2nd and 3rd trimester were identified by applying the latent-class trajectory model (LCTM) (R, package “lcmm”; function “hlme”) [24], a flexible semi-parametric approach that simplifies heterogeneous populations into homogeneous clusters or classes. We tested for optimal class numbers from K = 2 to K = 6, selecting the model based on a comprehensive consideration of several criteria [17, 25, 26]: lowest Bayesian information criteria (BIC) value, mean posterior probability greater than 0.7, relative entropy greater than 0.5, the proportion of estimated trajectory classes (with the smallest group including at least 5% of individuals), and the clinical meaning of each trajectory. We fitted linear, quadratic and cubic group models separately to select the optimal polynomial degree. According to the above criteria, the random quadratic proportional model with three classes was demonstrated to be the best fit. The number of weight measurements for each gestational week and parameters of LCTM for different populations were presented in Tables S2 and S3.

We applied the latent trajectory models to longitudinal weight data among all the pregnant women, firstly. Considering the potential influence of GDM on weight management and its impact on estimating GWG patterns, we then fitted latent trajectory models to longitudinal weight data collected in non-GDM and GDM group, respectively.

Measurements of offspring anthropometric outcomes

The measurements of offspring anthropometric outcomes before 36 months included weight (kg) and length (cm), which were taken by specially trained research nurses at each child health examination. The length and weight of offspring were used to calculate age- and sex-specific standardized child weight z-scores, length z-scores, and BMI z-scores, according to the World Health Organization’s Growth standard for children [27]. Z-scores is the preferred measure for allowing the comparison between children of different ages and sex. Children with age- and sex-specific BMI z-scores ≥ 2 were defined as overweight/obesity. Due to the small number of children with obesity, we did not conduct further separate analyses for overweight children and children with obesity to ensure sufficient statistical power. Meanwhile, due to the small number of underweight offspring, we did not consider underweight as an outcome in our study.

Covariates

The covariates included socio-demographic factors such as maternal age at delivery (years), maternal educational level (junior high school or less, senior high school, college or higher, and unknown), parity (primiparous, multiparous, and unknown), gravidity, and maternal early pregnancy weight (kg). These variables were selected because they are known to influence GWG trajectory and childhood growth and development. To further explore the independent effect of GWG trajectory, and after considering the established effects of maternal height [28], gestational age [29] and mode of delivery [30] on childhood growth patterns, we adjusted for maternal height (cm), gestational weeks at delivery (weeks) and mode of delivery (vaginal delivery, cesarean section, and unknown). Furthermore, based on the impact of birth weight and length [31, 32], as well as feeding practices [33], on subsequent growth and development, we adjusted for anthropometric measurements at birth and the duration of exclusive breastfeeding (< 3 months and ≥ 3 months).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables and categorical variables were expressed as the mean ± SD and frequencies (%), respectively. T-tests and Pearson Chi-square tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables between women with and without GDM, respectively. Similarly, ANOVA tests and Pearson Chi-square tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables among different GWG trajectory classes, respectively. For estimating the associations between GWG trajectory and mean offspring anthropometric outcomes from 1 to 36 months, we used the generalized estimating equations (GEE) models with the auto-regressive 1 correlation structure. By applying the auto-regressive 1 correlation structure, the increased within-subject correlation of closer measurements was accounted. Then, these above models were further adjusted for the covariates mentioned, and adjusted β with standard error (se) and adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were presented.

To further explore whether the effects of GWG trajectories are influenced by the total amount of GWG, we made additional adjustments to the total weight gain in sensitivity analysis. Additionally, in sensitivity analysis, the classification of offspring overweight/obesity status was based on the reference provided by the National Health Commission of China [34] and analyses were restricted after excluding women with pregnancy-induced hypertension. All analyses were performed using the statistical software R version 4.2.2. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P values < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic characteristics

Among the total of 13,424 pregnant women, the mean maternal age was 29.00 ± 4.04 years old, and the mean early-pregnancy BMI was 21.52 ± 3.02 kg/m². 17.8% of pregnant women were classified as overweight/obesity, and 62.2% were primiparous. Of the total, 2440 (18.2%) pregnant women were diagnosed with GDM, while 10,984 (81.8%) were classified as having normal glucose tolerance (NGT). When compared to women without GDM, those with GDM were older and had a higher proportion of overweight/obesity (26.2% vs. 15.9%) and multiparity (37.5% vs. 31.3%). More detailed characteristics of participants included were presented in Table S4.

Patterns of GWG trajectory

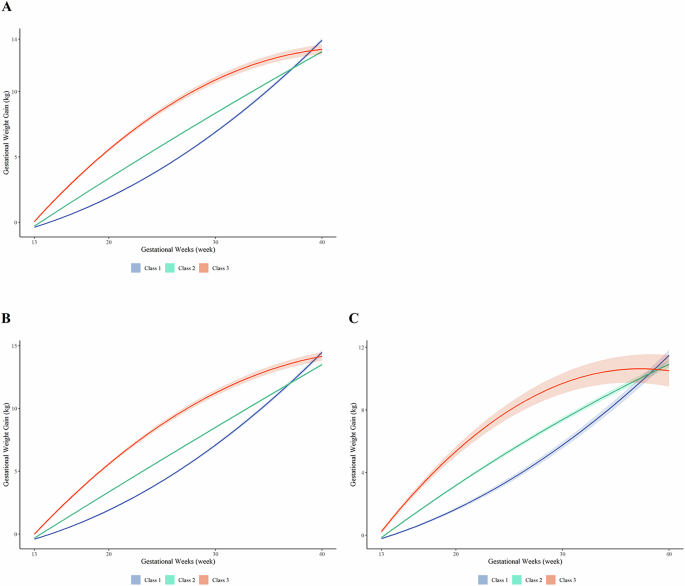

Among all participants, three GWG trajectory classes were identified (Fig. 1A): the Slow-Rapid pattern (25.7%), the Moderate pattern (64.5%) and the Rapid-Slow pattern (9.8%). The Slow-Rapid pattern showed slow GWG rate initially, followed by higher GWG rate in the third trimesters. The Moderate pattern showed GWG rate maintained a stable growth trend in GWG in second and third trimester. Conversely, the Rapid-Slow pattern showed high GWG rate initially, followed by slower GWG rate in third trimesters. Similar trajectory classes were identified in non-GDM (Fig. 1.B) and GDM group (Fig. 1.C).

A Patterns of gestational weight gain trajectory among all pregnancy women; B Patterns of gestational weight gain trajectory among women without GDM; C Patterns of gestational weight gain trajectory among women with GDM. The trajectory of GWG were modeled using the latent class analysis, and three distinct GWG trajectory were identified. The Slow-Rapid pattern (Class 1) showed slow GWG rate initially, followed by higher GWG rate in the third trimesters. The Moderate pattern (Class 2) showed GWG rate maintained a stable growth trend in GWG in second and third trimester. Conversely, the Rapid-Slow pattern (Class 3) showed high GWG rate initially, followed by slower GWG rate in third trimesters.

Among all pregnant women, as well as in the non-GDM and GDM groups, participants in the Slow-Rapid pattern exhibited the highest mean early-pregnancy BMI values, whereas those in the Rapid-Slow pattern had the lowest (Tables 1 and S5). The estimated total GWG and proportion exceeding the IOM guideline were highest in the Rapid-Slow pattern but lowest in the Moderate pattern (Table 2). Among all participants and non-GDM group, offspring of mothers with the Slow-Rapid pattern had the lowest mean birth weight and those of mothers with the Rapid-Slow pattern had the highest, while this trend was not observed in the GDM group (Table 1).

Effects of GWG trajectories on offspring anthropometric outcomes from 1 to 36 months

Table 3 presented the associations between GWG trajectory and offspring anthropometric outcomes among all participants. Offspring born to mothers with the Slow-Rapid pattern significantly showed lower length z-scores (β = −0.084; se = 0.015), compared to those born to mothers with the Moderate pattern, while offspring of mothers with the Rapid-Slow pattern significantly showed higher length z-scores (β = 0.083; se = 0.022). No significant differences of other anthropometric outcomes were observed among the different GWG trajectory classes.

Similarly, Table 4 showed the associations of GWG trajectory with offspring anthropometric outcomes among women without GDM. Offspring whose mother exhibited the Slow-Rapid pattern significantly showed lower length z-scores (β = −0.096; se = 0.018), compared to those of mothers with the Moderate pattern, while offspring whose mother exhibited the Rapid-Slow pattern significantly showed higher length z-scores (β = 0.099; se = 0.023). There were no significant differences among the different GWG trajectory classes in terms of other anthropometric outcomes.

Additionally, the effects of GWG trajectory on offspring anthropometric outcomes among women with GDM were displayed in Table 4. In comparison with the Moderate pattern, the Rapid-Slow pattern was significantly associated with increased offspring weight z-scores (β = 0.093; se = 0.046), BMI z-scores (β = 0.113; se = 0.052) and the risk of overweight/obesity (OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.76).

Sensitivity analysis

The associations between GWG trajectory and offspring weight z-scores, length z-scores, and BMI z-scores remained consistent after adjusting for total GWG during pregnancy across all participants, as well as in both the non-GDM and GDM groups (Tables S6 and S7).

The associations between GWG trajectory and the risk of offspring overweight/obesity were consistent across all participants, and the non-GDM and GDM groups (Table S8), when applying the China criteria to classify offspring overweight/obesity status.

Furthermore, after excluding women with pregnancy-induced hypertension from all participants, the non-GDM and GDM group (Table S9 and S10), the overall results remained consistent. The only exception was that the significant association between the Rapid-Slow pattern and higher BMI z-scores was no longer observed among the GDM group (Table S11).

Discussion

To our acknowledge, this is the first study that modeled GWG and investigated its associations with early offspring growth based on the GDM status. We identified three GWG trajectory patterns, which showed significant associations with offspring anthropometric measurements from 1 to 36 months, with varying effects observed in the non-GDM and GDM groups. The Rapid-Slow pattern was associated with higher length z-scores in all participants and women without GDM, while the Slow-Rapid pattern was linked to lower length z-scores. However, among women with GDM, early high GWG was notably associated with increased offspring weight and BMI z-scores, as well as a higher risk of overweight/obesity.

Prior studies have indicated that capturing the dynamic changes of GWG would be more helpful in determining when to monitor changes in weight [17]. This is particularly important for women with GDM, as these individuals may exhibit different patterns of weight gain due to factors such as pre-pregnancy obesity or medication management after diagnosis [35]. Additionally, some previous research suggested that different GWG standards should be developed for GDM and non-GDM populations, respectively [36, 37]. However, this opinion remains controversial. We argue that applying latent class trajectory models to model GWG trajectories in GDM and non-GDM populations, respectively, and investigating their effects could provide valuable insights into the differential effects of GWG in these groups.

We fitted GWG trajectory separately for the overall population, the GDM and non-GDM group, with three GWG trajectories identified in each group. The majority of women exhibited the Moderate pattern, characterized by steady weight gain that closely similar to the IOM recommendations [5]. We observed that despite similarities in the GWG trajectories group between the GDM group and non-GDM group, the total GWG and rate of GWG were slower among the GDM group compared to the non-GDM group. This is similar to a previous study, indicating differences in weight progression between individuals with GDM and those with NGT [20].

In the overall population and those without GDM, we observed a significant correlation between higher GWG in later trimester and offspring lower length z-scores during 1–36 months, whereas higher GWG in earlier trimester was associated with higher length z-scores. Although these findings highlight the importance of managing GWG for offspring length development, we did not identify associations between GWG trajectory and other indicators of growth and development. This differs from previous studies indicating significant associations between maternal higher GWG patterns and childhood overweight/obesity [19] and weight [18]. Discrepancies in study characteristics or a focus on specific time points for offspring growth and development rather than repeated measurements may explain the lack of consistency. Furthermore, previous research have not explored the association between GWG trajectory and offspring length.

However, what is noteworthy is the distinct impact observed within the GDM population, where earlier high weight gain was significantly associated with higher weight z-scores, BMI z-scores, and an increased risk of overweight/obesity in offspring. Previous studies have only reported a few findings regarding the overall impact of GWG on offspring growth and development among GDM populations. For example, Leng et al. found that, among women with GDM, excessive GWG beyond the IOM recommendation was associated with an increased risk of childhood overweight/obesity from 1 to 5 years old [38]. However, our study examined the entire trajectory of GWG, rather than just the amount of GWG, distinguishing it from previous research. Previous evidences suggests that the GWG pattern reflects different body compositions. Earlier weight changes primarily reflect alterations in maternal components such as adipose tissue [39, 40], leading to metabolic abnormalities in the intrauterine environment. While later weight changes predominantly reflect components supporting fetal growth, such as the placenta and amniotic fluid [39]. Meanwhile, maternal hyperglycemia is known to lead to abnormal intrauterine conditions, such as increased transfer of glucose and free fatty acids across the placenta, thereby increasing the likelihood of offspring overweight/obesity [41]. Previous studies suggest that GDM or variations in glucose metabolism may alter the effects of GWG [42, 43] and another study demonstrated that the presence of GDM enhanced the association between GWG and newborn adiposity [44]. These findings above indicate that the presence of GDM may amplify the impact of earlier high weight gain on the fetus, exposing it to greater energy effects and thus affecting offspring growth. Therefore, in the GDM population, exposure to earlier high weight gain is more likely to influence offspring weight.

In this study, we employed a LCTM to provide dynamic weight gain changes during pregnancy, instead of focusing on total GWG or GWG rate. This offers valuable insights to monitor GWG progress effectively, which is specifically beneficial for women with GDM. Furthermore, our study is the first to focus on GDM status in examining the association between GWG trajectory and offspring growth. The findings revealed disparities in GWG effects between women with and without GDM, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the influence of GDM on GWG. Additionally, we utilized multiple indicators to assess early offspring growth, distinguishing our study from previous studies that often reported a single indicator. However, there are several limitations should be noted. Firstly, the majority of participants only had one weight record in first trimester of pregnancy, hindering the description of early GWG trajectory. While, in fact, pregnant women commonly have 0–2 kg weight gain in the first trimester and the weight of the first prenatal care in early pregnancy is usually used by obstetric clinicians as individual-specific baseline to monitor GWG, which may mean that our study has more practical application value [45]. Secondly, due to the low prevalence of overweight/obesity individuals among the GDM participants, further subgroup analysis was not conducted. Furthermore, our study sample was limited to pregnant women in Zhoushan city, China, the generalizability of our findings to other regions may be limited. Lastly, some potential confounders such as medication management and diet after GDM diagnosis was lack.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate significant associations between GWG trajectory patterns and early offspring anthropometric measures, with varying effects observed among women with and without GDM. GWG trajectory only influenced offspring length across all participants and women without GDM. However, earlier high weight gain was notably linked to increased offspring weight, BMI, and the risk of overweight/obesity among women with GDM. These results underscore the importance of weight management during pregnancy, especially in high-risk populations prone to GDM. Further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and develop targeted interventions to optimize GWG management for improving offspring outcomes.

Responses