Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition-defined malnutrition coexisting with visceral adiposity predicted worse long-term all-cause mortality among inpatients with decompensated cirrhosis

Introduction

The onset of cirrhosis is always insidious, and it can progress to more advanced stages like hepatocellular carcinoma and acute decompensation. The latter is manifested with variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy (HE), accounting for approximately 2.4% of the global deaths in 2019 [1]. It has been suggested that the etiologies of cirrhosis are ever-changing, probably due to improved therapy against chronic viral hepatitis, healthcare policy refinement, and life style modification. Of note, global alcohol consumption is estimated to continuously grow, and the burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)-associated cirrhosis tends to rise steadily in alignment with the epidemics of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity. Moreover, another entity designated as metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is anticipated to apparently influence the etiologies of cirrhosis. MAFLD implicates hepatic steatosis with factors in relation to metabolic dysfunction, T2DM or obesity without the need to rule out alternative reasons for chronic liver diseases [2, 3]. Therefore, the burden of MAFLD-associated cirrhosis is speculated to increase over time, alluding a pivotal role of obesity as the pathogenic or precipitating factor among this vulnerable population.

Regarding obesity, a dilemma exists since there is a lack of universally accepted and well-built diagnostic criterion. For instance, the validity and reliability of body mass index (BMI), a typical metric assessing obesity, have been considerably curtailed in the context of cirrhosis, given that proportional patients may experience various magnitudes of fluid retention [4]. Another inherent flaw of BMI is its inability to differentiate distinct adipose tissue compartments, that is, subcutaneous, visceral, intramuscular, and intermuscular adiposity. It is highlighted that visceral fat area (VFA) and associated indices have been linked to the risk of inferior outcomes in contrast to BMI [5]. Intriguingly, the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue defined by increased VFA refers to a novel terminology “visceral obesity”, serving as a more reliable indicator of obesity [6, 7]. We previously clarified a synergically negative impact of muscle wasting and VFA-defined obesity on prognosis among hospitalized patients with cirrhosis [8]. On the other hand, another term “visceral adiposity” indicative of high visceral to subcutaneous adipose tissue area ratio (VSR) has also been applied in the existing literature [9,10,11].

Malnutrition is another nutritional extremity in relative to obesity, whose prevalence is around 5% to 92% among patients with cirrhosis according to different assessing toolkits [12]. Despite there are no unanimous diagnostic criteria for malnutrition, the close connection between undernourished status and a wide range of poor outcomes has been validated in patients with advanced liver diseases. Notably, the presence of cirrhosis-related malnutrition is linked to worse survival conditions, dysregulated body composition, decreased health-related quality of life as well as increased likelihood of complications [13,14,15,16]. In hopes of standardizing and harmonizing the malnutrition diagnosis, a novel consensus on the criteria, known as the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM), has been launched and endorsed in 2018 [17]. This recommendation argues a two-step modality covering initial nutritional risk screening by any validated tools along with subsequent phenotypic/etiologic parameters for comprehensive evaluation [18]. The confirmatory malnutrition diagnosis relies on at least one phenotypic plus one etiologic criterion, whose effectiveness, performance, and validity have been corroborated in versatile clinical scenarios [19,20,21]. In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) has addressed a phenomenon pertaining to “a double burden of malnutrition” where obesity, undernutrition in addition to diet-related non-communicable diseases concurrently occur, representing a real, growing, and challenging health concern globally [22]. In this regard, some researchers have investigated the predictive value of nutritional status in combination with BMI-defined obesity [23,24,25]. However, there is a paucity of data utilizing VFA-defined visceral obesity as a more reliable surrogate, and current evidence review retrieves only one article in the context of patients with rectal malignancies [26]. Furthermore, the utility of VSR-defined visceral adiposity and its combined effect with malnutrition on prognosis is still elusive. In this study, we hypothesized that malnutrition coexisting with visceral obesity or visceral adiposity may exhibit incremental risk of deaths among hospitalized patients with cirrhosis.

Subjects and methods

Study population

This study enrolled hospitalized patients with cirrhosis on account of acute decompensation to the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (TJMUGH) from 2018 to 2021. Acute decompensation was defined by the presence of at least one of the following complications: gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage (GEV) on endoscopic examination [27], ascites (fluids in the abdominal cavity) classified by the international Ascites Club [28], HE categories in terms of the West Haven Criteria in addition to severe jaundice suggestive of serum total bilirubin ≥51 µmol/L [29, 30]. Inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) confirmatory cirrhosis in terms of laboratory, radiologic, endoscopic, elastographic, or histopathologic data and (3) informed consent to participate. Exclusion criteria: (1) presence of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) upon index admission; (2) without computed tomography (CT) images 3 months prior to hospitalization; (3) liver malignancies or other extrahepatic cancers and (4) refusal to regular follow-up. ACLF definition conformed to the guideline established by the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver, including coagulation abnormalities (prothrombin time-international normalized ratio [PT-INR] ≥1.5) and jaundice (total bilirubin ≥85 µmol/L) alongside HE and/or ascites within 4 weeks in the patients experiencing chronic liver disease or cirrhosis [31]. Totally, 295 inpatients were left for final analysis (see flow chart in Fig. S1). This study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the TJMUGH ethics committee. Written informed consent was provided.

Clinical and biochemical data

Clinical and biochemical data were obtained as follows: age, sex, cirrhosis etiologies, hemoglobulin, white blood cell counts (WBC), platelet, total bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatinine, sodium, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), albumin, PT-INR, comorbidities (hypertension, coronary heart diseases (CHD) and T2DM). Some indicators/scoring systems concerning inflammation and liver disease severity were calculated as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), Child-Turcotte-Pugh score/class and model for end-stage liver disease-sodium (MELD-Na) score. In current study, proportional patients with cirrhosis had ascites, thus the dry weight was retrieved by subtracting 15%, 10%, and 5% for bulky, moderate, and mild ascites, respectively, and additional 5% for peripheral edema [32]. The primary outcome of current study was 1-year all-cause mortality. Outcome data were collected through self-report from patients or their relatives (i.e., survival on telephone follow-up/clinic consultation) and validated through review of city-wide electronic medical records (i.e., date of death and death reasons). The patients were censored if they remained alive at one year and the last follow-up date was December 2022.

Computed tomography-demarcated parameters

The study population underwent abdominal CT scans for a variety of indications including disease severity stratification, disease progression monitoring along with malignancy transformation surveillance. All images were derived from a spectral CT scanner (Discovery 750 HD 64-row, GE corporation, U.S.), and then, analyzed and read by two independent observers (G.Y.G. and W.T.Y.). The final results were validated by a senior radiologist with sufficient expertise (H.H.W.). The body composition compartments regarding skeletal muscle and various adipose tissue were determined in terms of tissue-specific Hounsfield Unit (HU) at the third lumbar vertebra level (L3) by using an open-source project based on R2010a Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, U.S.). The specific CT thresholds of skeletal muscle, subcutaneous adipose tissue, and visceral adipose tissue were −29 ~ 150 HU, −190 ~ −30 HU, and −150 ~ −50 HU, respectively. The skeletal muscle index (SMI) was calculated by dividing the L3 muscle area by height in square (m2). The diagnosis of visceral obesity was defined by VFA > 100 cm2 for both sexes [33]. Moreover, visceral adiposity was determined according to our previous report, that is, VSR > 1.47 for males and VSR > 1.29 for females [34].

Malnutrition screening and assessment

The diagnosis of malnutrition was established conforming to the 2-step manner GLIM criteria. The first step indicated a Royal Free Hospital‐Nutritional Prioritizing Tool (RFH-NPT) ≥ 1 to identify the subjects at malnutrition risk. Regarding RFH-NPT, this analytic metric has been recommended by the International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism [35, 36]. One study showed that the RFH-NPT independently predicted clinical deterioration and transplant-free survival in patients with chronic liver disease [37]. Another investigation implicated that the RFH-NPT was one of the most accurate screening tools in detecting malnutrition in cirrhosis, whilst other six tools exhibited insufficient performance [38]. Taken account of this recommendation which has been further confirmed by us and others, thus we selected the RFH-NRT in current study for stratifying nutritional status in cirrhosis [37, 39]. Next, malnutrition was determined when one of the three phenotypic criteria was fulfilled since patients with decompensated cirrhosis were inclined to dramatical disease burden meeting the etiologic criterion [40]. In detail, non-volitional weight loss was defined by >5% or >10% weight loss within or over 6 months; low BMI value was defined as <18.5 kg/m2 or <20 kg/m2 among subjects with age <70 years or ≥70 years; decreased muscle mass was in agreement with our previously outcome-based SMI thresholds to evaluate sarcopenia [34].

Statistical analysis

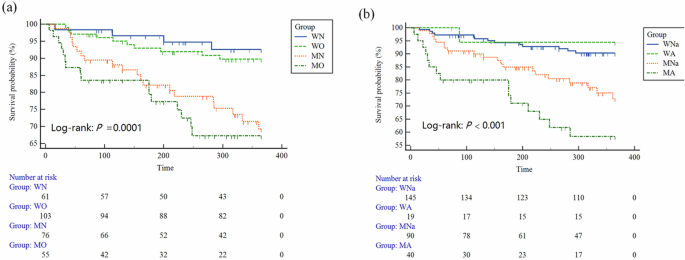

The study population was categorized into four groups in terms of their visceral obesity and nutritional status: well-nourished non-visceral obesity group (WN), well-nourished visceral obesity group (WO), malnourished non-visceral obesity group (MN) and malnourished visceral obesity group (MO). Furthermore, another four groups by applying VSR were constructed as follows: well-nourished non-visceral adiposity group (WNa), well-nourished visceral adiposity group (WA), malnourished non-visceral adiposity group (MNa) and malnourished visceral adiposity group (MA) group. The descriptive data were presented as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and simple frequencies (proportions, %) for categorical variables. Multiple comparisons among continuous data were conducted by applying Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test. The Fisher’s exact test or Chi-squared test was used for comparisons regarding categorical data. Univariate and Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess risk factors associated with 1-year all-cause mortality among inpatients. The entry criterion was P < 0.05 in the univariate model. We included MELD-Na, NLR, the presence of ascites, albumin and stratified groups by GLIM-defined malnutrition and CT-demarcated visceral obesity/adiposity, but excluded WBC, creatinine, CTP score, alcoholic etiology, total bilirubin, PT-INR and BMI to avoid collinearity with the aforementioned variables. The selection of MELD-Na relied on its advantageous over the CTP score, in particular, on the basis of objective variables rather than subjective assessment of clinical manifestations (i.e., HE and ascites) [41]. The Kaplan–Meier curves concerning 1‐year all‐cause mortality were performed to demonstrate survival status and compared with log-rank test. Statistical significance was suggestive of a 2-sided P < 0.05. SPSS 23.0 (IBM) and MedCalc 20.0.3 (MedCalc) were used.

Results

Totally, 295 inpatients with cirrhosis were recruited, and the sex predominance was female (51.5%). The median CTP and MELD-Na score were 8 and 7.6 points, respectively. Cirrhosis-associated complications comprised ascites in 176 patients (59.7%), HE in 21 patients (7.1%) and infection in 38 patients (12.9%). Regarding comorbidities, the presence of hypertension, CHD, and T2DM was observed in 86, 22, and 66 patients, respectively. Nutritional risk screening with the RFH-NPT identified 202 (68.5%) subjects. Following diagnostic criteria, 131 (44.4%) and 158 (53.6%) patients were identified as exhibiting malnutrition and visceral obesity, respectively. Regarding sex discrepancies, 53.1% of males and 36.2% of females were identified as malnourished, while 61.5% of males and 46.1% of females as visceral obesity. In this regard, the numbers of patients in WN, WO, MN, and MO groups were 61 (20.7%), 103 (34.9%), 76 (25.8%), and 55 (18.6%), respectively.

The baseline clinical and biochemical features can be found in Table 1. There were significant differences concerning sex, age, CTP score, MELD-Na score, NLR, total bilirubin, albumin, creatinine, sodium, WBC, SMI, BMI, the presence of hypertension, ascites, infection and cirrhosis etiologies. However, no significant differences were observed regarding PT-INR, ALT, AST, LDL-C, platelet, hemoglobin, CHD, T2DM, GEV and HE. Notably, patients in the MO group were inclined to be male (P < 0.001), and had highest CTP score (P < 0.001), MELD-Na score (P < 0.001), highest levels of total bilirubin (P = 0.047), NLR (P < 0.001), creatinine (P = 0.003), WBC (P < 0.001), lowest levels of albumin (P = 0.001), sodium (P < 0.001), BMI (P < 0.001), and experienced most prevalent hypertension (P < 0.001), ascites (P < 0.001), and infection (P = 0.015).

During the follow-up period, a total of 50 deaths has been recorded, and the reasons can be attributed to organ failure in 28, infection in 11, HE in 4, massive bleeding in 3, cardiovascular disease in 2 and cerebrovascular disease in 2 subjects. The survival rates in the WN, WO, MN, and MO groups were 94.3%, 90.3%, 73.7%, and 70.9%, respectively. Figure 1a illustrated the Kaplan–Meier curves in terms of nutritional and visceral obesity status among patients hospitalized for acute decompensation (log-rank test: P = 0.0001). In the univariate Cox regression analysis, MO was associated with 461% higher risk of death compared with MN (Table S1). However, in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, HE, GEV, MELD-Na, and albumin were independently associated with 1-year all-cause mortality, while MO dropping out of the model (Table 2).

a The groups were stratified in terms of nutritional and visceral obesity status. b The groups were stratified in terms of nutritional and visceral adiposity status. WN well-nourished non-visceral obesity group, WO well-nourished visceral obesity group, MN malnourished nonvisceral obesity group, MO malnourished visceral obesity group, WNa well-nourished non-visceral adiposity group, WA well-nourished visceral adiposity group, MNa malnourished non-visceral adiposity group, MA malnourished visceral adiposity.

Intriguingly, emerging evidence has highlighted that the distribution of adipose tissues rather than their volumes represented a closer relationship with disease severity [11, 42]. Therefore, we further performed in-depth investigation by using VSR to identify individuals with concurrent malnutrition and visceral adiposity in the same cohort. As a result, a total of 294 were left for final analysis (one patient were excluded due to inaccessible subcutaneous adiposity tissue area). Accordingly, the baseline features of another four groups designated as WNa (145, 49.2%), WA (19, 6.4%), MNa (90, 30.5%), and MA (40, 13.6%) were demonstrated in Table 3. Patients in the MA group were prone to be male (P < 0.001), and had highest CTP score (P < 0.001), MELD-Na score (P < 0.001), highest levels of NLR (P = 0.003), total bilirubin (P < 0.001), creatinine (P = 0.002), WBC (P = 0.020), lowest levels of albumin (P = 0.001), sodium (P < 0.001), SMI (P < 0.001), BMI (P < 0.001), and experienced most prevalent ascites (P < 0.001) and infection (P = 0.031). Figure 1b also demonstrated the Kaplan–Meier curves in terms of nutritional and visceral adiposity status (log-rank test: P < 0.001). The survival rates in the WNa, WA, MNa, and MA groups were 91.0%, 94.7%, 77.8%, and 62.5%, respectively. In the univariate Cox regression analysis, MA was associated with 450% higher risk of death compared with WNa (Table S2). Moreover, in the multivariate Cox regression analysis (Table 4), MA was independently associated with 1-year all-cause mortality (hazard ratio: 2.48, 95% confidence interval: 1.06, 5.79, P = 0.036).

Discussion

In this study, we elaborate on the predictive value of coexisting malnutrition and excessive accumulation of abdominal adipose tissue on long-term prognosis among inpatients with decompensated cirrhosis. Our preliminary results implicated that VSR-defined visceral adiposity rather than VFA-defined visceral obesity was independently associated with 1-year all-cause mortality in the context of cirrhosis. Moreover, patients with cirrhosis in the MA group exhibited the worst survival status compared with those in other three groups. Taken together, it is imperative to delicately manage the nutritional status and provide personalized treatment for this vulnerable subgroup with the purpose of improving prognosis.

The prevalence of malnutrition among cirrhosis is of great variation due to heterogenous target populations and mixed screening/assessing tools which give rise to challenges surrounding comparisons between different studies. To offset aforesaid barriers, the GLIM criteria have been advocated to harmonize diagnosis across multiple healthcare settings, pathophysiological entities and geographic areas [17]. More recently, the relationship between GLIM-defined malnutrition and a variety of dire health consequences has been verified in the field of hepatology [14, 15, 43, 44]. In current study, malnourished patients accounted for more than two-fifths of participants enrolled (44.4%), which highlighted the clinical importance to evaluate nutritional conditions, taking into account cirrhosis as a predisposing state to nutrients imbalance (excess or deficiency) [45].

Another issue warranted further in-depth exploration is the combined effect of malnutrition and abdominal adipose tissue accumulation. Actually, the overlap between malnutrition and obesity/adiposity appears to be underestimated in clinical practice, therefore, limited data has clarified their synergistic impact [26]. This is similar to another unique phenotype, known as sarcopenic obesity in the circumstance of fat mass masking underpinning muscle depletion [46]. Malnutrition may serve as both a cause and a consequence of obesity, indicative of an abnormal pathophysiological state triggered by inadequate, unbalanced, or excessive macronutrients/micronutrients assimilation [47, 48]. In this obesity background, malnutrition can result from a wider availability of cheap nutrient-deficiency foods, responsible for a positive energy balance and micronutrients deficiency. In addition, massive adipose tissue can sequester vitamins instigating subsequently their decreased concentrations in the circulation. For instance, vitamin D deficiency has been linked to the risk of abdominal obesity in adults [49]. Neito et al. reported that blood levels of vitamin D, zinc, and other micronutrients were decreased in patients with decompensated cirrhosis [50]. In this regard, we herein found that there was 18.6% and 13.6% of patients categorized into the MO and MA group, respectively. Of note, the proportions of MO or MA are likely to grow since cirrhosis attributable to NAFLD continues to increase, raising intensive attention and specific concern to this subgroup [1].

The synergic impact of abdominal adipose tissue accumulation and malnutrition in cirrhosis is multifactorial and complicated. Referring to survival status analysis, Kaplan–Meier curves showed that the survival rate was lowest in the group experiencing concomitant malnutrition and obesity/adiposity regardless of categories in terms of VFA or VSR. However, MA remained its independently predictive role for long-term mortality while MO dropped out of the multivariate Cox regression model. Actually, emerging evidence has proved that the distribution of abdominal adipose tissue exhibits more intimate correlation with underlying disease severity. For instance, one study recruiting patients with cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation revealed that higher VSR was an independent predictor of histologic VAT inflammation, and the authors verified the effectiveness of CT-quantified VSR as a prognostic marker for dire outcomes [42]. Moreover, fat deposit in visceral sites may lead to insulin resistance and persistent chronic inflammation [51, 52]. The existing literature has clarified that both inflammatory milieu and insulin resistance are predisposing factors with contributory role to the progression of malnutrition and visceral adiposity [47, 53]. Collectively, the coexistence of malnutrition and visceral adiposity may pinpoint a more aggressively dysmetabolic imbalance in the context of cirrhosis.

The worse prognosis of patients in the MA group means more delicate management as well as personalized treatment should be provided. Some academic institutional consensus have recommended a reduced caloric intake of 20–25 kcal/kg/day but increased protein intake up to 2.5 g/kg in patients with cirrhosis and obesity [54, 55]. This hypocaloric diet may be accompanied with weight loss, but other concerns regarding decreases in lean mass and bone mineral density can not be underestimated [56]. Notably, significant weight loss can give rise to ascites, potentially HE and sarcopenia in decompensated cirrhosis, thus tailored strategy to ensure a slow weight loss and sufficient protein intake is of utmost importance [57]. A cluster of pragmatic actions for patients with cirrhosis and visceral adiposity has been proposed: empowerment of patients, prescription of nutritional support and exercise (aerobic and resistance training) even for decompensated subjects by adapting to their health conditions [58].

This study has several limitations. First, the applicability of VSR to determine visceral obesity is controversial. This metric would be equivalent in subject with large or small amounts of visceral adipose tissue and subcutaneous adipose tissue at the same time, resulting in misclassification of patients [59]. Second, we assumed that all patients with cirrhosis at decompensating stage met the etiologic criterion pertinent to disease burden which may overestimate the prevalence of malnutrition. Last, the relative small size of patients with malnutrition and visceral adiposity may underpower the comparison among different groups, although statistical significance already existed with this sample size.

In conclusion, this study elaborated on a synergically negative impact of coexisting malnutrition and VSR-defined visceral adiposity, that was a double burden, on long-term mortality among hospital inpatients. It is imperative to delicately manage the nutritional status and provide personalized treatment in this vulnerable subgroup with the purpose of improving prognosis.

Responses