Haemaphysalis longicornis subolesin controls the infection and transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus

Introduction

Ticks naturally carry and transmit various arboviruses1. These viruses can cause severe human diseases, including encephalitis, thrombocytopenia, hemorrhagic fever, and meningitis, which inflict tens of thousands of infections and cause a large number of deaths worldwide2. Unfortunately, most tick-borne viral diseases lack effective vaccines or therapeutics.

Typically, ticks incidentally feed on virus-infected hosts or co-feed with virus-infected ticks on naïve hosts and acquire infectious viruses from the hosts3,4,5. Subsequently, these viruses invade the tick gut cells and disseminate throughout the hemocoel to infect the hemolymph, fat body, and salivary glands6. Successful infection of the salivary glands allows viral transmission by infected ticks to the naïve host or co-fed ticks during the next blood feeding.

The skin, the interface of virus-host-tick interactions, is the first vertebrate organ that the virus encounters during its journey from the tick salivary glands to the host’s body7. Proinflammatory environments were created, and immune cells were recruited at virus-infected tick feeding loci, providing a vehicle for transmission between infected and uninfected co-feeding ticks that is independent of patent viremia8,9. Currently, co-feeding transmission has been observed for most tick-borne viruses10.

The use of chemicals is the primary method of controlling ticks and tick-borne diseases. With the emergence of chemical resistance in ticks11, targeting key molecules involved in tick blood feeding or tick-borne disease transmission is regarded as a novel control measure12,13. A series of molecules, including subolesin (SUB), have been identified as anti-tick vaccine candidates. SUB is a promising candidate for anti-tick vaccines14. SUB, the ortholog of other invertebrate and vertebrate akirins, plays essential roles in blood feeding, development, reproduction and immunity in ticks15. In Haemaphysalis longicornis, silencing of SUB by RNAi or immunization of animals with recombinant SUB impaired tick blood feeding13,16. In Rhipicephalus microplus, RNAi-mediated knockdown of SUB inhibited the infection of Anaplasma marginale and Babesia bigemina17. However, the roles of SUB in tick-borne virus infection and transmission remain poorly understood.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) caused by the SFTS virus (SFTSV) is an emerging tick-borne disease with a mortality rate of up to 30% in Asia18,19. SFTSV is a newly recognized member of the Phlebovirus genus in the family of bunyaviruses, primarily transmitted by H. longicornis20,21,22. In our previous studies, infected ticks were generated by experimental injection, and SFTSV transmission occurred when the infected ticks fed on vertebrate hosts23. Here, the effect of SUB on SFTSV infection was investigated using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), and the possible underlying mechanism was explored using RNA-seq. Furthermore, the role of SUB in viral transmission was evaluated using gene knockdown and active immunization. Our results characterized the role of SUB in SFTSV infection and transmission and may be useful for the development of novel strategies for tick-borne disease control.

Results

SUB depletion attenuates SFTSV replication in the salivary glands of unfed ticks

To explore the effect of SUB on SFTSV infection, dsRNA-mediated SUB depletion was conducted by injecting dsRNA of SUB into unfed females of H. longicornis (Fig. 1A). The relative mRNA expression and viral load were measured using qPCR analysis. The results showed that the relative levels of SUB and SFTSV RNA in the females injected with dsSUB decreased by 85.7% and 81.3%, respectively, compared with the females injected with dsEGFP (Fig. 1B).

A Schematic representation of the study design. The SUB gene was silenced by dsRNA in H. longicornis. Ticks were intrahemocoelically injected with dsEGFP served as a control. After 6 days, dsRNA-treated ticks were intrahemocoelically infected with SFTSV. After rearing 6 days, the whole body, gut and salivary glands were collected for further experiments. The relative levels of SUB transcript and SFTSV RNA after SUB knockdown were measured in the whole body (n = 18 per group) (B), gut (n = 20 per group) (C) and salivary glands (n = 20 per group) (D) using qPCR analysis. E Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) showing the variation in SFTSV amounts in salivary glands of H. longicornis after SUB knockdown (Scale bars, 25 μm). Nucleoprotein (NP) of SFTSV was observed using anti-NP polyclonal antibodies and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (blue). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. Each point represents a single tick sample. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-tests in the left panel of (C) and Mann–Whitney tests in the others. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.005.

The relative SUB levels in the gut and salivary glands from the SUB-depletion group decreased by more than 50% (Fig. 1C, D). However, SFTSV RNA levels decreased only in the salivary glands, not in the guts, in the SUB-depletion groups. The inhibition of SFTSV infection in the salivary glands was also supported by immunofluorescence with an NP polyclonal antibody (Fig. 1E). These results demonstrate that SUB depletion attenuates SFTSV replication in the salivary glands of unfed female ticks.

SUB specifically modulates the expression of an array of genes involved in protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum

To explore how SUB affects SFTSV infection in the salivary glands, gene expression profiles were compared between the infected tissues pretreated with dsSUB and dsEGFP through RNA sequencing. Venn diagram analysis revealed that 98 genes were exclusively regulated in the salivary glands (55 upregulated and 43 downregulated) after SUB depletion. Six genes, including SUB, were downregulated in both the gut and the salivary glands (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 2). RNA-seq analysis of the salivary glands was further validated with qPCR using six selected differently expressed genes (coefficient = 0.954, p = 0.0031) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The 365 bp SUB dsRNA was identified to have 15 predicted double-stranded 22-nt siRNAs (Supplementary Table 3), which did not target any genes besides SUB among the differently expressed genes in the salivary glands. The pathway, protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum, was significantly enriched in genes that were exclusively regulated in the salivary glands (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that no OTE was predicted in the 365 bp SUB dsRNA and SUB plays a role in regulating tick protein modification exclusively in the salivary glands.

A Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in the infected tissues pretreated with dsSUB versus dsEGFP. Red upward triangles indicate significantly upregulated genes and green upward triangles indicate significantly downregulated genes in dsSUB-treated tissues. B Scatterplot showing the KEGG pathways of the genes specifically regulated in the infected salivary glands after SUB knockdown. Significantly enriched pathways are indicated in red.

SUB knockdown impaired SFTSV transmission

The observation of significantly reduced viral load in tick salivary glands upon pretreatment with dsSUB prompted us to determine whether SUB knockdown affects SFTSV transmission to vertebrate hosts and co-infestation nymphs during blood feeding. Six days post-dsSUB injection and another 6 days post-SFTSV infection, two infected females were co-fed with an uninfected male on each mouse (Fig. 3A). After 2 days, ten uninfected nymphs were joined. The viral burden was analyzed in mouse skin and nymphs after blood feeding. qPCR analysis revealed that upon co-feeding with infected females pretreated with dsSUB, a significantly decreased viral load (122-fold) was observed in engorged nymphs compared with the control group (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the viral load exhibited a 189-fold reduction in mouse skin from the dsSUB group compared with that in the dsEGFP group (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that SUB knockdown impairs of SFTSV transmission.

A Schematic representation of the study design. H. longicornis ticks were intrahemocoelically injected with 1 μg/500 nL dsSUB or dsEGFP as negative controls. Six days later, the ticks were intrahemocoelically injected with SFTSV (7.25 × 103 FFU) and maintained for 6 days to allow virus infection. Subsequently, KM mice were bitten by SFTSV-infected females (each mouse was bitten by two infected females and one uninfected male) in a feeding chamber. After 2 days, ten uninfected nymphs were placed in the chamber. Engorged nymphs and mouse skin were collected and subjected to determine the viral burden by qPCR analysis. The relative levels of SFTSV RNA in engorged nymphs (n = 21 for engorged nymphs co-fed with dsEGFP-treated females; n = 16 for engorged nymphs co-fed with dsSUB-treated females) (B) and skin (n = 5 per group) (C) bitten by infected females. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney tests in (B) and Student’s t-tests in (C). *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.005.

Suppression of SUB represses tick feeding

SUB is an anti-tick vaccine candidate. To assess its effects on the feeding activity and survival of ticks in the presence of SFTSV infection, the survival and engorged rates of females and nymphs were statistically analyzed. The survival and engorged rates were significantly affected after SUB knockdown in infected females. The survival rate decreased to 20% in females in the dsSUB group compared with that in the dsEGFP group (Fig. 4A). The average engorged rates were 10% and 80% in females in the dsSUB and dsEGPF groups, respectively (Fig. 4B). However, the survival and engorged rates were not significantly different between nymphs co-fed with females from the dsSUB and dsEGFP groups (Fig. 4C, D). These results demonstrate that SUB knockdown impairs tick feeding and decreases survival.

A Average survival rate of females per mouse. B Average engorgement rate of females per mouse. C Average survival rate of nymphs per mouse. D Average engorgement rate of nymphs per mouse. n = 5 mice per group. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-tests in (A) and Mann–Whitney tests in (B–D). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01; n.s. not significant.

Effect of SUB depletion on the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines and the monocyte markers at the skin interface during SFTSV transmission

The skin, the interface of virus-host-tick interactions, plays an important role in tick-borne pathogen transmission, especially in co-feeding transmission. The expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines at the skin interface during SFTSV transmission after SUB knockdown was investigated using qPCR analysis. The majority of genes were not significantly regulated in the skin bitten by SUB-knockdown female ticks compared with control ticks. However, the chemokine C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2) was significantly downregulated in the skin of the dsSUB groups compared with that in the dsEGFP group (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. 2).

The expressions of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (A), as well as the inflammatory monocyte markers (B), were analyzed in the skin bitten by SUB-knockdown female ticks compared with control ticks using qPCR analysis. TLR4 Toll-like receptor 4, TRAF6 TNF receptor-associated factor 6, IFNGR2 interferon gamma receptor 2, TREM1 triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1, CCR3 C-C motif chemokine receptor 3, CCL2 chemokine C-C motif ligand 2. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney tests for CCL2 and Student’s t-tests for the others (n = 5 per group). **p < 0.01; n.s. not significant.

CCL2 is capable of recruiting inflammatory monocytes to the site of infection in mice24. To assess the change in inflammatory monocyte counts at the skin interface during SFTSV transmission after SUB knockdown, the relative mRNA levels of the monocyte markers (CD11b, CD115 and Ly6C) were determined by qPCR analysis. The average mRNA levels of the three markers were all decreased in the skin bitten by SUB-knockdown female ticks compared with control ticks, and the differences in CD11b and Ly6C reached statistical significance (Fig. 5B).

Active immunization with SUB reduces the acquisition of SFTSV by naïve nymphs in co-feeding model

To evaluate the antibody levels of SUB in sera samples from immunized mice at 0, 14, 28, 42, and 56 d, indirect ELISA and Western blot experiments were performed (Fig. 6A). Purified recombinant SUB protein migrated as approximately 30-kDa single bands on SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 3A) and was confirmed by mass spectrometry. After the first booster, the signals for coated SUB protein at OD450 nm were significantly higher in the SUB-immunized group and increased with increasing booster doses. After the third booster dose, the average OD450 nm reached 3.2 in the SUB-immunized group, whereas in the control group, the mean value was 0.2 (Fig. 6B). The Western blot results further showed that antibodies produced in the SUB-immunized group could react with the SUB protein band, while no reaction was observed using sera from the control group (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

A Schematic representation of the study design. KM mice were injected with recombinant SUB or PBS as a control and boosted three times at 2-week intervals. Two weeks after the last immunization, infected females were added to the feeding chamber along with one uninfected male. After 2 days, ten uninfected nymphs were added to the feeding chamber. B Antibody responses of immunized mice (n = 8 per group) measured using indirect ELISA. Each point represents the average OD450 nm in each group. The relative levels of SFTSV RNA in engorged nymphs (n = 40 for engorged nymphs fed on SUB-immunized mouse; n = 43 for engorged nymphs fed on the control mouse) (C) and skin (n = 7 for the control group (One sample was excluded because the GAPDH transcript could not be detected by qPCR); n = 8 for the SUB-immunized group) (D) bitten by infected females. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-tests for the data at 14 days, 42 days and 56 days in (B) and Mann–Whitney tests for the others. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.005; n.s. not significant.

To observe the effect of antibodies against SUB on the transmission of SFTSV, the SFTSV levels of nymphs co-fed with infected females were determined through qPCR analysis. The results suggested that the SFTSV levels of nymphs co-fed with infected females on mice immunized with SUB were decreased by 11.2 times compared with that on the control mice (Fig. 6C). qPCR analysis revealed that the skin from immunized mouse bitten by infected females had a lower average viral load than that from the control mice (Fig. 6D). However, this change was not statistically significant. These results suggest that immunization with SUB can interfere with SFTSV transmission between infected and uninfected ticks co-feeding on mice.

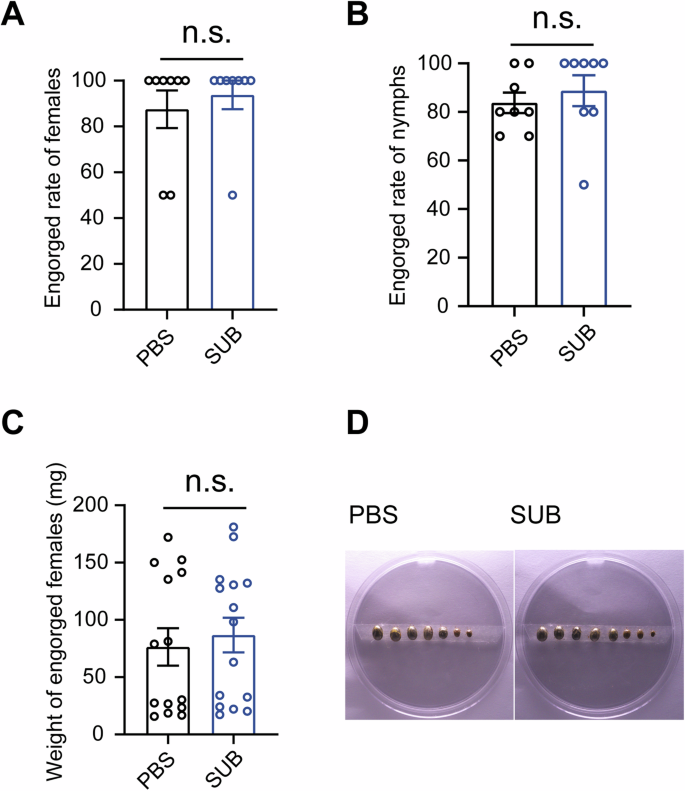

Active immunization with SUB has no effects on tick engorgement during SFTSV transmission

The observation of decreased tick survival and engorgement after SUB depletion prompted us to investigate whether antibodies targeting SUB affect tick survival and engorgement. In the experiment, we noted that no ticks died, and the engorge rate of females fed on SUB-immunized mice was comparable to that of females fed on control mice (Fig. 7A). Similar results were observed for nymphs (Fig. 7B). Moreover, there was no significant difference in the average weight of engorged females between the experimental and control groups (Fig. 7C). The images of the collected females also supported that SUB immunization had no effect on female blood feeding (Fig. 7D). Taken together, these results suggest that SUB immunization has no effects on tick engorgement during SFTSV transmission.

Effects of SUB immunization on female (A) and nymph (B) engorgement (n = 8 per group), engorged female weights (n = 14 for engorged females fed on SUB-immunized mouse; n = 15 for engorged females fed on the control mouse) (C) and photographs of females (D). Photographs are representative of two independent experiments. Other results were pooled from two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney tests. n.s. not significant.

Discussion

The emergence of an anti-tick vaccine targeting arthropod-protective antigens is a novel advancement in vaccinology. A series of anti-tick vaccine candidates, including SUB, have been demonstrated to reduce the transmission of tick-borne pathogens. Previous studies have suggested that SUB vaccination can reduce the transmission of B. burdoferi, A. marginale, A. phagocytophilum, and B. bigemina but not TBEV17,25,26. Our results suggested that targeting SUB affects the transmission of SFTSV in the co-feeding transmission mode.

As a tick-protective antigen, the effect of SUB knockdown in ticks on pathogen infection has been explored for many tick-borne pathogens, including bacteria and parasites. For example, the infection levels of Anaplasma marginale, A. pahocytophilum, and E. canis decreased in SUB-silenced ticks compared with those in control ticks in D. variailis27,28. In contrast, F. tualrensis infection level increased after SUB knockdown. In R. microplus, the infection of A. marginale and B. bigemina dramatically decreased after SUB knockdown17. In this study, we further showed that the infection level of tick-borne virus SFTSV decreased after SUB silencing in the salivary glands of H. longicornis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which the effects of SUB knockdown on tick-borne viral infection have been assessed, which further advances our knowledge of the role of SUB in tick-borne pathogen infection. Therefore, tick SUB targeting by dsRNA interferes with infection by pathogens, including bacteria, parasites, and viruses.

Despite the important role of SUB in regulating pathogenic infections, the possible mechanisms remain unexplored. In this study, transcriptome analysis revealed that protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum was significantly enriched after SUB knockdown in infected salivary glands of H. longicornis. A previous study has reported that unfolded protein response in protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum participates in SFTSV infection in the human HEK-293 cell line29. These results imply that SFTSV infection may be regulated by a similar mechanism in ticks and mammalian hosts and that SUB controls SFTSV infection depending on the mechanism. The detailed mechanism underlying the inhibition of SFTSV infection after SUB knockdown needs to be elucidated.

Many studies have shown a correlation between arbovirus transmission from infected to uninfected co-feeding ticks and infection at the skin site where tick feeding occurred in co-feeding transmission, which is independent of viremia30. The cutaneous host responses to virus-infected tick feeding are more inflammatory9,31. Infectious viruses are produced by migratory monocytes/macrophages8,30,31. Our study showed a decrease in CCL2 levels following SUB knockdown. CCL2 recruits monocytes and macrophages for inflammation at the skin site32,33. Several scenarios can be envisioned where SUB knockdown could impair SFTSV transmission from infected ticks to the skin and co-fed uninfected ticks. First, the lower level of viral replication in the salivary glands results in a reduction in the viral load in SFTSV transmission. Second, SUB knockdown decreases CCL2 at the skin site, which leads to a reduction in the number of monocytes for the production of infectious viruses (Fig. 5). Third, SUB knockdown impairs blood feeding, which impairs SFTSV transmission. With any or all of these hypotheses, SUB knockdown seems to be an effective approach to hinder the transmission of SFTSV.

Most tick-borne viruses can be transmitted by co-feeding transmission10, which supports a higher rate of viral transmission than viremic transmission in some studies3. Our results further support the idea that SFTSV can also be transmitted by co-feeding transmission. In the transmission mode, we found that vaccination with recombinant SUB protein significantly reduced SFTSV transmission from infected ticks to co-fed uninfected ticks. SUB vaccine reduced the transmission of bacteria and parasites17,25. However, SUB vaccine did not affect TBEV transmission in co-feeding transmission mode26. The difference between SFTSV and TBEV may be because they belong to different families. Mice bitten by ticks infected with SFTSV can survive, but those bitten by ticks infected with TBEV may not. This may also be caused by the different methods, such as different immunization times and the times uninfected nymphs were added to the chamber. Moreover, immunization with SUB did not affect tick infestation during SFTSV transmission. Virus-vector-host interactions with other arbovirus, such as Zika virus, dengue virus, and Orthotospovirus, can modulate the host environment to facilitate vector-feeding behavior and viral transmission34,35. Therefore, we hypothesized that SFTSV infection and transmission counteract the effects of SUB vaccination, which needs to be verified in further studies.

Taken together, for the first time, we demonstrated that H. longicornis SUB is important for SFTSV infection and transmission. H. longicornis SUB knockdown could decrease SFTSV infection in tick salivary glands, transmission from ticks to vertebrate hosts, and transmission from infected ticks to co-fed uninfected ticks. Active immunization of H. longicornis SUB impaired SFTSV transmission from infected ticks to co-fed uninfected ticks. These findings improve our understanding of the role of SUB in the infection and transmission of tick-borne pathogens and offer a viable strategy for developing vaccines for SFTSV control.

Methods

Ticks, mice, and viruses

The colony of H. longicornis was raised in our laboratory as previously described36,37. Male KM mice, aged 6 weeks, were obtained from Changsha Tianqin Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (SPF, SCXK [Xiang] 2019–0014) and were subjected to a 5-day adaptation feeding period prior to the experiment. SFTSV Wuhan strain (GenBank accession numbers: S, KU361341.1; M, KU361342.1; L, KU361343.1) was used in this study38.

Gene silencing and viral infection in H. longicornis

A 365 bp dsRNA of SUB was synthesized using a T7 RiboMAXTM Express RNAi System kit (Promega, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. EGFP was used to produce the EGFP dsRNA for the control group. The primers used for dsRNA production are listed in Supplementary Table 1. One microgram of dsRNA was injected into the hemocoel of H. longicornis females using a microinjector (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, CA, USA). After 6 days, the injected ticks were inoculated intrahemocoelically with SFTSV (7.25 × 103 FFU), as previously described23,37. The ticks Infected ticks were collected for sampling or subjected to feed on KM mice for further investigation.

Expression and purification in recombinant subolesin in Escherichia coli

The open reading frame of SUB was synthesized and inserted into the pET28a (+) vector. The recombinant SUB protein was induced in E. coli grown in LB medium as previously described39. E. coli cells were collected by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 10 min, resuspended in Tri-HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 8.0), and sonicated for 20 min. All the following procedures were performed at 4 °C. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, the precipitates containing recombinant protein were resuspended in Tri-HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 8.0), and then incubated for 30 min. The above procedure was repeated three times, and the standstill times were 20, 10 and 10 min. After centrifugation and resuspension, Tri-HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 8.0) containing 8 M urea was added to dissolve proteins. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation and used for further analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR analyses of gene expression and viral burden

Total RNA samples were prepared from the gut, salivary glands, and whole body of H. longicornis as well as KM mouse skin. The cDNA of each sample was synthesized using HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). qPCR reactions were performed using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). Translation elongation factor EF-1 alpha (ELF1A) was used as an internal control for tick samples, while glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the internal control for mouse samples. The relative gene expression levels and viral burden were calculated using the ΔΔCT method. The primers used for qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Indirect fluorescence assay

After cleaning with 75% ethanol and sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the ticks were dissected and the salivary glands were collected. The salivary glands were washed in fresh cold sterile PBS and embedded in NEG 50TM medium (Thermo Scientific Richard-Allan Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The medium-embedded block was then cut into 5 μm sections using a cryomicrotome CryoStar NX5 (Thermo Scientific Richard-Allan Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Tissue sections were placed onto positively charged microscope slides and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 1 h. After removing the paraformaldehyde, the tissue sections were pretreated with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h and then washed with PBST three times. The samples were then incubated with anti-nucleoprotein (NP) polyclonal antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing three times with PBST, Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) were added. After incubation and washing, slides were added with ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI and covered with a glass coverslip. The fluorescence was observed using a Nikon ECLIPSE Ni microscope.

Transcriptomic analysis of genes regulated by SUB

Total RNA was extracted from the salivary glands or the guts of ten ticks from each group, and mRNA was purified. cDNA libraries were constructed and sequenced using the BGI DNBSEQ platform (BGI, Shenzhen, China). Fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (FPKM) were used to calculate the normalized gene expression value. The DEseq2 package (version 1.40.2) in R (version 4.3.1) was used to conduct differential gene expression analysis. The genes were considered as differentially expressed with a Q-value < 0.05 and |Fold Change| > 2. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of genes that are differentially expressed only in the salivary glands was performed using phyper function in R (version 4.3.1). The top 10 enriched pathways were plotted using ggplot2 package (version 3.5.1) in R (version 4.3.1).

Prediction of off-target effects (OTE)

The prediction of OTE was performed using the previously described method with modifications40,41. Briefly, OligoWalk (version 1.0) was employed to identify suitable siRNAs that could be generated from the cleavage of a 365 bp dsRNA derived from SUB42. Default parameters were used, and a length threshold of 22 nt was set because the siRNAs produced by H. longicornis are 22 nt in length43. The significantly up- and downregulated genes in the salivary glands were subjected to be screened against all the predicted sense and antisense siRNAs using RNAhybrid (version 2.1.2)44. From positions 1 to 16, there is complete base pairing, with the restriction that only one internal loop and/or bulge is allowed from positions 17 to 22.

Co-feeding transmission model

Two infected females and one uninfected male were placed in a feeding chamber on the back of the mouse. Each mouse was randomly assigned to a cage position. After 2 days, ten uninfected nymphs were placed in the feeding chamber. The survival and engorgement rates of females and nymphs were recorded. Mouse skins and almost half of the engorged nymphs (random selected) were collected and used to evaluate the viral burden.

Immunization of mice with SUB to assess influence of SUB antibodies on viral transmission

Four mice received an initial immunization of recombinant SUB (60 μg) or PBS in complete Freunds’ adjuvant. They were subsequently boosted three times at 2-week intervals with recombinant SUB (30 μg) or PBS in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. Before each immunization and after 2 weeks from the final boost, serum samples were collected and evaluated through ELISA and/or Western blot using HRP labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). The immunized mice were subjected to evaluated influence of SUB antibodies on viral transmission using the co-feeding transmission model with infected females (6 days after SFTSV infection) as described above. The experiment was performed twice independently.

Ethics statements

All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the China Laboratory Animal Nursing and Use Regulations and with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Hainan Medical University. The ARRIVE guidelines were followed (Supplementary Note 1). Before collecting skin tissue, KM mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg). At the end of the experiment, all mice were euthanized through inhalation of isoflurane (1–4%), and cervical dislocation was then used to ensure death.

Statistical analysis

Animals were allocated to each group randomly. The sample size was chosen to provide sufficient power to compare control and treatment group. Data analysis and graph preparation were conducted with GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.2). Unpaired Student’s t-tests or Mann–Whitney tests were used for statistical analysis and were contingent on the data distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test). If the data fails to meet the assumption of normality, the Mann–Whitney test will be performed; otherwise, the unpaired Student’s t-test will be used. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Details of the statistical analysis of the transcriptome data are described in the corresponding methods.

Responses