Hand kinematics, high-density sEMG comprising forearm and far-field potentials for motion intent recognition

Background & Summary

Surface electromyography (sEMG) signal of the underlying muscle contains neural control information, and has gained momentum for the development of human-machine interaction (HMI)1,2,3. The recognition of human motion intention using sEMG provides intuitive control commands for the HMI scenarios, such as advanced prosthetic hands4,5, exoskeletons6,7, and virtual or augmented reality8,9. For decades, the sEMG-based movement intent recognition have focused on analysing forearm muscles during discrete and specific hand movement patterns. However, the myoelectric control performance is susceptible to uncontrolled circumstances in daily life10,11,12,13,14, let alone to proportionally manipulate multiple degrees of freedoms (DoFs) equipped with modern dexterous prostheses.

Theoretically, motor neurons innervate motor unit via the neuromuscular junction, and sEMG signal is the indirect reflection of motor unit action potentials15. The measurement of high density sEMG (HD-sEMG) allows to decompose the discharge characteristics of motor neurons, which is promising to improve the robustness of myoelectric control16,17,18,19. Additionally, the researches on sEMG based gesture recognition were mostly limited to upper forearm muscles, in the clear case of prosthetics usage20,21,22,23. Nevertheless, much more than rehabilitation technology, the development of myoelectric interfaces as consumer electronics has attracted increasing attention in the past few years24,25,26,27. The motion intent recognition interface using wrist sEMG signal is more socially accepted by the general consumers28.

A few studies have proven that the wrist sEMG signals are feasible to recognize motor intention, and more than 75% recognition accuracy was achieved to predict hand gestures in offline even real-time manners29,30,31. Moreover, far-field potentials were extracted from HD wrist sEMG using blind source separation method and were verified to classify individual and combined finger motions32. Due to the highly crosstalk contaminated wrist sEMG signals recorded over the convergence of multiple muscle tendons, the relatively poor myoelectric control performance is yet to be improved by sophisticated machine learning techniques. To transfer the prior knowledge of forearm-based myoelectric gesture recognition to wrist-worn neural interface, it is of great significance to investigate the firing characteristics of motor neurons within forearm (near-field) and wrist (far-field) muscles synchronically. Therefore, recording databases comprising HD-sEMG of forearm-wrist muscles and hand kinematics is imperative to develop novel algorithms and methods for researchers. However, acquiring reliable datasets including both forearm and wrist HD-sEMG signals is cumbersome that may limit research progress.

Currently, there are several existing databases for sEMG signals recorded from the wrist or forearm, such as SEEDS33, GrabMyo34, KIN-MUS UJI35, CapgMyo36 and Hyser37. All these databases are very useful for gesture recognition research without time-consuming data collection procedure. Despite these efforts, dataset on the integrated forearm-wrist HD-sEMG and hand kinematics is still missing. A comparison of the aforementioned datasets and our HD sEMG signals of Forearm-Wrist and hand KINematics (HD-FW KIN) is presented in Table 1. Beyond the conventional sEMG acquisition configuration, the record of HD-sEMG allows the decomposition of the neural drive into the form of motor unit action potential trains (MUAPt). Moreover, the wrist HD-sEMG is promising to open up the opportunity of exploring far-field potentials for wrist-worn neural interface.

To fill in the gaps in publicly available databases, this study presents an open-access HD-FW KIN dataset using the state-of-the-art experimental setup. The proposed HD-FW KIN comprises 448-channels HD-sEMG data of forearm and wrist captured from 21 healthy participants performing multiple trials of 20 different hand gestures including individual finger movements, combined finger movements, wrist movements, and finger static press. Moreover, the kinematics of the finger movements is simultaneously recorded through a data-glove, and two levels of finger static press force are also synchronously measured together with HD-sEMG by a custom-made platform. We believe that the hand kinematics and finger force data are important for the development proportional control in addition to the classical pattern recognition method. The presented HD-FW KIN dataset would be helpful to promote the research of hand motion recognition, hypotheses testing, algorithms validation for many scientific domains, including but not limited to prosthetics, rehabilitation, wearable device, and human-computer interaction.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-one healthy subjects (19 males and 2 females) aged 21-35 years (26.47 ± 3.71 years) participated in the study. All participants were right-handed without neuromuscular disorders. Their forearm length ranged from 23-30.5 cm (25.47 ± 2.29 cm), forearm circumference ranged from 23-29 cm (25.87 ± 2.00 cm), and wrist circumference ranged from 14.5-18 cm (16.79 ± 0.93 cm). The participants were recruited from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University via WeChat platform with social multimedia application, advertising the experimental goal and procedure. All the interested respondent candidates were given a full description of detailed information about the experiment, such as methods, purpose and protocol, to ensure that the participants were well-informed. Before the experiment, the participants had read and signed the informed consents including data sharing. To anonymise participant information, the participants were itemized as subject_01-subject_21 in the database. The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Approval No.: E20230257I) and the experiments were in accordance with Helsinki Declaration.

Setup for data acquisition

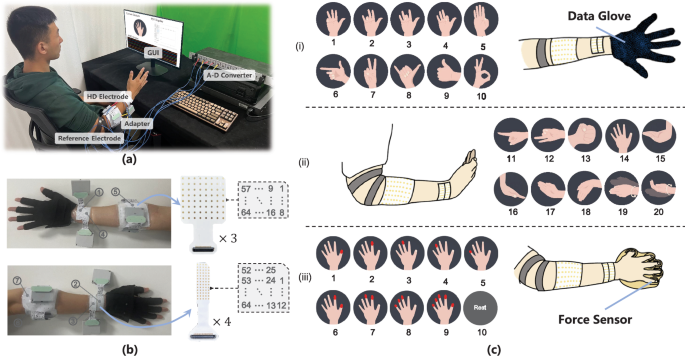

The experimental setup was arranged for simultaneous forearm-wrist HD sEMG and hand kinematics recording during muscular activities, as well as synchronous measurement of HD sEMG and finger forces. Specially, the HD sEMG signals were recorded in monopolar mode using a RHD Recording System (Intan Technologies, California, United States) designed for electrophysiology data acquisition (Fig. 1(a)). The HD sEMG signals were sampled at 2000 Hz with 16-bit resolution.

Experimental setup of data collection: (a) subjects were seated comfortably in front of a graphical user interface (GUI) on the computer screen, and the subjects performed experiment procedures according to the visual feedback of GUI; (b) electrodes placement for concurrent recording of HD-sEMG signals at the wrist and forearm, and hand kinematics were synchronously collected by data-glove; (c) designated hand motions in the datasets, in subgraph (i) and (ii), they are: 1-little finger flexion, 2-ring finger flexion, 3-middle finger flexion, 4-index finger flexion, 5-thumb flexion, 6-middle-ring-little finger flexion, 7-thumb-ring-little finger flexion, 8-index-middle-ring finger flexion, 9-four finger flexion, 10-thumb and index flexion, 11-index finger point, 12-thumb-index-middle finger flexion, 13-hand close, 14-hand open, 15-wrist flexion, 16-wrist extension, 17-radial deviation, 18-ulnar deviation, 19-pronation, 20-supination, respectively; the dynamic finger movements of gestures 1-13 were recorded by data-glove; in subgraph (iii), they are fingers flexion with specific pressure on force sensors: 1-thumb pressing, 2-index finger pressing, 3-middle finger pressing, 4-ring finger pressing, 5-little finger pressing, 6-thumb and index pressing, 7-index and middle pressing, 8-middle-ring-little finger pressing, 9-all finger pressing, and 10-rest, respectively.

Three 8 × 8 HD sEMG electrode arrays (192 channels in total; GR10MM0808, OT Bioelettronica, Italy) with a 10 mm inter-electrode distance were attached on the muscles around forearm (Fig. 1(b)), and the distance of electrode to the elbow olecranon was set as one-third of the forearm length. Additionally, the wrist HD sEMG were collected using four 5 × 13 electrode grids (64 channels with 4 mm distance, 256 channels in total; GR04MM1305, OT Bioelettronica, Italy), and the electrodes surrounded the circumference of the wrist adjacent to the head of ulna, with two grids attached on the anterior part and the other two grids on the posterior part of wrist. The ground electrode and reference electrode were placed around the olecranon separately (Fig. 1(a)). Before electrode attachment, the skin surface was cleaned with alcohol and the electrodes were treated by conductive gel to ensure contact stability and signal quality.

Hand kinematics were captured by a 5DT Data Glove 14 Ultra (5DT Inc. USA), and the sampling frequency was set at 200 Hz which is far more than the movement frequency of fingers. The angles recorded by each channel of the data glove are: 1-Angle of metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of thumb, 2-Angle of interphalangeal joint of thumb, 3-Angle between thumb and index finger, 4-Angle of MCP joint of index finger, 5-Angle of proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint of index finger, 6-Angle between index finger and middle finger, 7-Angle of MCP joint of middle finger, 8-Angle of PIP joint of middle finger, 9-Angle between middle finger and ring finger, 10-Angle of MCP joint of ring finger, 11-Angle of PIP joint of ring finger, 12-Angle between ring finger and little finger, 13-Angle of MCP joint of little finger, 14-Angle of PIP joint of little finger. Moreover, the isometric press forces of the five fingers were recorded using a custom-made force measurement device (RFP 602, Runeskee Co.Ltd, China) with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz. The synchronization between HD sEMG and hand kinematics (data glove or isometric finger force) was controlled via a TTL trigger to corresponding devices.

Experimental protocol

The experiment consisted of two sessions to acquire the forearm-wrist HD sEMG data along with hand kinematics and finger force, respectively. In experimental session one, participants were seated with their right forearm toward the ground in a resting position. At the beginning of the experiment, the data-glove was calibrated for each subject. The data-glove signal of each finger was normalized to 0-1 corresponding to full extension and flexion. Thereafter, subjects were instructed to perform 20 hand and wrist gestures at a normal effort level, following by a visual instruction presented on the computer screen in front of the subjects. These frequently used gestures in daily activities were shown in Fig. 1(c), they were: 1-little finger flexion, 2-ring finger flexion, 3-middle finger flexion, 4-index finger flexion, 5-thumb flexion, 6-middle-ring-little finger flexion, 7-thumb-ring-little finger flexion, 8-index-middle-ring finger flexion, 9-four finger flexion, 10-thumb and index flexion, 11-index finger point, 12-thumb-index-middle finger flexion, 13-hand close, 14-hand open, 15-wrist flexion, 16-wrist extension, 17-radial deviation, 18-ulnar deviation, 19-forearm pronation, 20-forearm supination. Data acquisition started with two dynamic flexion and extension repetitions followed by one 5-second isometric contraction. The period of one dynamic contraction was set as 2 seconds, flexing to target gestures (1 s) and returning to initial position (1 s). Note that the dynamic data of gestures 14-20 were unable to be collected by data-glove, thus only steady state maintenance data were acquired. The static isometric contraction data of gestures 14-20 were also valuable for gesture recognition research. One continuous data collection of 21 gestures (including a 5-second rest) was defined as a trial, and six trials were performed for each gesture. A 2-minutes resting period was provided between adjacent trials to prevent the impact of muscle fatigue. Eventually, a total of 156 dynamic contractions (6 trials × 2 repetitions × 13 gestures) and 126 isometric contractions (6 trials × 21 gestures) were recorded from each subject in this session.

The second session was designed to synchronously collect forearm-wrist HD sEMG signals and isometric finger flexion forces. Subjects sat on a chair with their right hand placed on a platform with comfortable and effortless position, and each finger was placed on top of corresponding force sensor. Prior to this experimental session, the maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) level of each individual finger for each subject was calibrated. The visual feedback of their finger press force values was displayed on a front computer screen (Fig. 1(a)). Subsequently, subjects were asked to maintain 5-second steady finger press at designated MVC for each individual finger and combined fingers as the following sequence: 1-thumb pressing, 2-index finger pressing, 3-middle finger pressing, 4-ring finger pressing, 5-little finger pressing, 6-thumb and index pressing, 7-index and middle pressing, 8-middle-ring-little finger pressing, 9-all finger pressing, and 10-rest, as shown in Fig. 1(c)–(iii). A 5-second resting was arranged after each steady finger press. Each individual finger and combined fingers pressing was performed for 6 trials at 20% and 40% MVC, respectively (12 trials in total). There was a 2-minutes relaxing between each trial to avoid muscle fatigue.

Data processing

A 50 Hz notch filter was applied to eliminate the powerline noise that might decrease the signal quality of recorded HD sEMG, hand kinematics and finger force. The HD-sEMG signal was undergone high-pass filtering at 0.13 Hz to remove DC components and low-pass filtering at 1kHz to eliminate high-frequency noise, while preserving the remaining signal for user-customized filtering. Furthermore, we provide a well-designed filter bank to facilitate user-friendly filtering. This approach allows users to conveniently process the signal according to their specific needs. Our goal is to offer users flexibility in signal processing to meet diverse research and application requirements. We believe that this data processing method provides users with more options and convenience, enabling them to effectively utilize HD-sEMG signals for research and practical applications.

Data Records

The data produced during the described experiment and methods are freely accessible and can be downloaded from38, which is a general-purpose repository that makes research outputs available in a shareable and discoverable manner. The database consists of forearm and wrist muscle activities of 21 able-bodied subjects while performing 21 hand gestures (including REST), and 9 individual or combined finger flexion under two force levels (20% MVC and 40% MVC). The HD-sEMG array contains 448 channels, each one representing a recording site. The first 256 channels belong to wrist HD-sEMG array, the remaining ones belong to forearm HD-sEMG array. The finger pressing force array contains 5 rows, each one representing a recording finger pressing force, in turn: 1-thumb, 2-index, 3-middle, 4-ring, 5-pinky. The data-glove array includes the normalized signals from 14 digital joints sensors. The sampling frequencies of the sEMG, the pressing force and the data-glove signals are set as 2000 Hz, 1000 Hz and 200 Hz, respectively. The format and content of the released repositories are described as follows.

The proposed repository includes three folders, as outlined in Table 2. The first folder contains data for experimental session one, which includes 21 participants, with a total of 12 (6 repetitions, and 2 types of movement including hand gesture and wrist movement) files in WFDB format (.dat and .hea file extension) for each participant. The second folder contains data for experimental session two, which includes 21 participants, with a total of 24 (6 repetitions, 2 types of movement with different MVC level, and 2 data source signals including sEMG and finger press force) files in WFDB format for each participant. The third folder contains data for experimental session one, which includes 10 participants, with a total of 12 (6 repetitions, and 2 data source signals including sEMG and angles of finger joints) files in WFDB format for each participant.

Technical Validation

The motivation of this HD-FW KIN dataset is to investigate the hand motion intention recognition via sEMG signals from wrist other than forearm. In order to extract the discharge characteristics of motor neurons, high density configuration is adopted to record sEMG signals. This section concentrates on ascertaining the quality and usability of acquired signals according to offline analyses. A brief analysis is performed to ensure the synchronization of the recorded HD sEMG, finger kinematics data, as well as finger pressing force. Furthermore, other demonstrations including gesture classification, hand kinematics prediction and finger flexion force analysis, are provided to verify the potential applications of the datasets.

Synchronisation of multiple signals

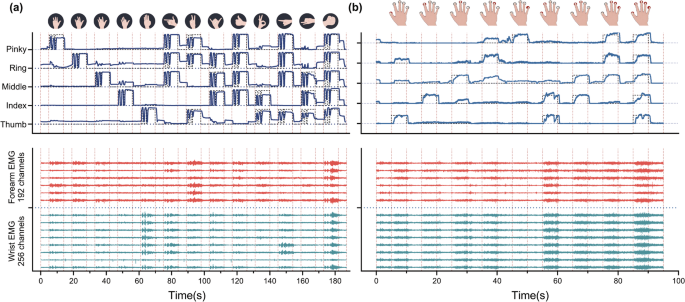

The synchronization of multiple signals including HD sEMG, hand kinematics and finger flexion force was validated to ensure reliable coupling analysis for further study. An example of the synchronization between the HD forearm-wrist sEMG and data-glove across a session of hand movements from a typical subject was shown in Fig. 2(a), and the data were from representative channels of HD forearm-wrist sEMG and the inner sensor of all five fingers integrated in data-glove. Figure 2(b) illustrated the synchronization between the finger pressing force and HD forearm-wrist sEMG during the finger flexion under 20% MVC.

Synchronisation among multiple signals: (a) illustration of synchronisation between the inner sensor of all five fingers (data-glove) and representative channels of HD forearm-wrist sEMG during an experimental trial of hand movements; (b) example of synchronisation between finger flexion force under 20% MVC and HD sEMG. The target motion curves and target force curves were represented by dotted lines. The representative channel 1, 33, 65, 97, 129, 161, 193, 225 were located at wrist, and the channel 257, 289, 321, 353, 385, 417 were placed over forearm.

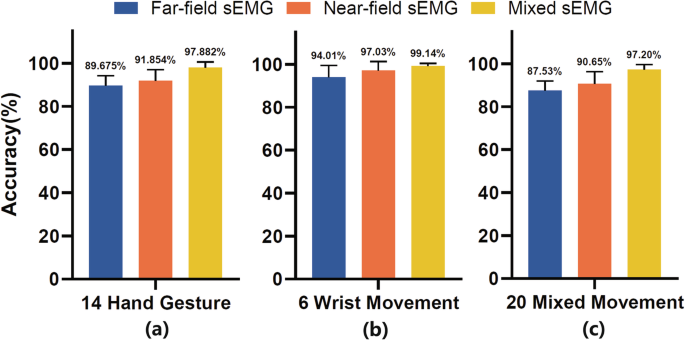

Gesture classification

To validate the performance of gesture classification for the datasets, we designed a set of paradigms to explore the impact of the gesture type and acquisition location of signal on the accuracy of gesture classification. The gesture movements were classified into two categories, namely hand gestures (motion 1-14, Fig. 1(c)) and wrist gestures (motion 15–20). There were a total three sets of data, the hand gesture dataset (14 motions), the wrist gesture dataset (6 motions), combination gesture dataset (20 motions). Moreover, the acquisition locations were also classified into two categories, namely wrist (far-field) HD-sEMG and forearm (near-field) HD-sEMG. With regards to acquisition location, there were three scenarios, namely, the far-field HD-sEMG, the near-field HD-sEMG and the mixed HD-sEMG.

To avoid dimensional disaster and reduce computational complexity, sixteen representative channels were selected with equispaced intervals from far-field and near-field HD-sEMG signals, respectively. The representative far-field and near-field sEMG signals were segmented into a series sliding windows. The window length and step length were set as 200 ms and 100 ms, respectively. Four-dimensional time-domain (TD) feature vectors11 were calculated from these sliding windows, namely, mean absolute value (MAV), waveform length (WL), zero crossing (ZC) and slope sign change (SSC). Subsequently, we employed a leave one out cross-validation strategy. Five of the six trials feature vectors were used to train the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) model, and the model was then tested on the last trial. The same procedure was repeated until all the trials had been used as testing trial. The classification accuracy was used for performance evaluation. The average accuracy of gesture classification was represented in Fig. 3, which was comparable to that of state-of-the-art reports31,32.

The classification accuracy of various HD-sEMG location datasets and gesture movements: (a) hand gestures; (b) wrist movements; (c) combined hand and wrist movements. Sixteen representative channels were respectively selected with equispaced intervals from far-field (channel 1, 17, 33, 49, 65, 81, 97, 113, 129, 145, 161, 177, 193, 209, 225, 241) and near-field (channel 257, 269, 281, 293, 305, 317, 329, 341, 353, 365, 377, 389, 401, 413, 425, 437) HD-sEMG signals to reduce computational complexity.

Hand kinematics prediction

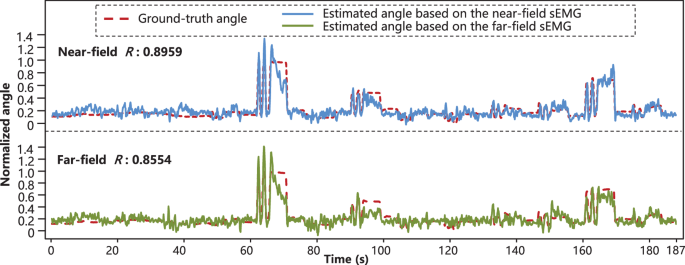

The paradigm of the hand kinematics dataset was complex, which seemed to be beyond the research scenario of existing works. Therefore, to verify the effectiveness of the recorded data, we applied more than one widely-used methods to the single case. Specifically, the root-mean-square (RMS) based method and the motor unit (MU) based method were adopted. The RMS-based method predicted hand kinematics based on the time-domain features and multi-linear regression (MLR) model. Firstly, the RMS were calculated for each channel of filtered HD-sEMG to obtain the feature vector. The calculation window length and step length were set to 300 ms (600 contiguous samples) and 100 ms (200 contiguous samples), respectively. Then, the MLR model of each finger was built by training data and evaluated by test data. During the evaluation process, the predicted hand kinematics were backward shifted by 200 ms (2 contiguous windows) because of the electromechanical delay on human physiological39.

The difference between the MU-based method and the RMS-based method was the feature vector that was input into the MLR model. Firstly, the HD-sEMG was decomposed to obtain the motor unit spike trains (MUSTs). To improve the number of decoded MUs, segment-wise convolutional kernel compensation (swCKC) method40 was adopted. The segmentation criteria of the swCKC is that each 9-second motion state and the 2.5-second motion state before and after it are taken as a segment. The MUSTs of test data were calculated by the separation parameters that were obtained on training data. Then, the firing rate (FR) of each MUST, which was the designed feature vector, was calculated within the sliding window whose parameters were the same as that of RMS-based method.

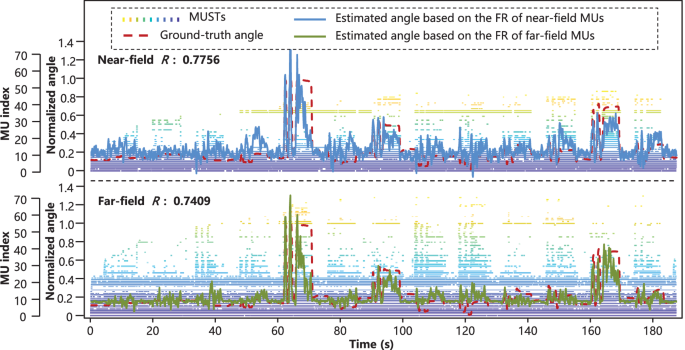

To observe the performance difference of different sensor location in hand kinematics prediction, all the methods were applied to the far-field and near-field sEMG signals. Figures 4 and 5 showed the ground-truth angle trajectory and estimated angle trajectory of the RMS-based method and the MU-based method, respectively. The R values (Pearson correlation coefficient41) of the RMS-based method on the near-field and far-field were 0.8959 and 0.8554, and those of the MU-based method on the near-field and far-field were 0.7756 and 0.7409, respectively. It was found that both explosive-state and steady-state could be effectively tracked. The performance of these methods on the far-field was only slightly inferior to that of near-field. The potential reason for the inferior performance of the MU-based method was as follow. The swCKC method was proposed for the scenario where the characteristic of the decoded MUs was invariant and the recruitment of new MUs would not occur40. However, the duration of a single trial was quite long, which increased the chances of MUAP change and some others42. Therefore, the separation parameters obtained from training data might become invalid on test data.

Ground-truth angle trajectories and estimated angle trajectories based on the RMS-based method (subject 3, proximal joint of the thumb finger, 4th trial was used as testing data and other trials were training data). The Pearson correlation coefficients of the near-field (forearm) and far-field (wrist) were 0.8959 and 0.8554, respectively.

MUSTs, ground-truth angle trajectories, and estimated angle trajectories based on the MU-based method (subject 3, proximal joint of the thumb finger, 4th trial was used as testing data and other trials were training data). The Pearson correlation coefficients of the near-field (forearm) and far-field (wrist) were 0.7756 and 0.7409, respectively.

Finger force analysis via motor neuron discharges

EMG-Force Regression

To verify the effectiveness of the force dataset, we adopted the MLR method to predict the force of each finger, which also provided the benchmark for future works. In addition, the MLR models were respectively established for the far-field and near-field, which aimed to study the performance difference of different sensor location in EMG-force regression. The establishment of the force regression model of a single field for a single MVC level contained the following steps. Firstly, the four-dimensional TD features11 were extracted from each sEMG channel. The calculation window length and step length were set as 300 ms and 100 ms, respectively. Secondly, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to reduce the dimensionality of the feature vector to 50. Thirdly, the MLR model of each finger, whose input was the dimension-reduced feature vector and output was the predicted force, was trained based on the least square method. Root mean square error (RMSE) between the estimated force and the ground-truth force for each test trial was used for performance evaluation. Considering the electromechanical delay on human physiological, the predicted force was backward shifted by 200 ms (2 contiguous windows) during the evaluation process. Similar to gesture classification, the leave one out cross-validation strategy was employed.

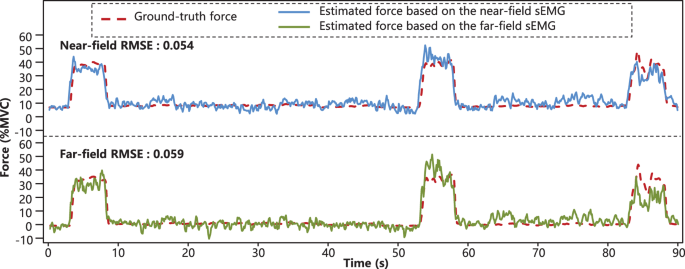

The summary RMSE results of the EMG-force regression of each subject were presented in Table 3. The average RMSE values of near-field across all the subjects were 6.25% MVC in 20% MVC situation and 11.09% MVC in 40% MVC situation, and those of far-field were 6.46% MVC in 20% MVC situation and 11.56% in 40% MVC situation. Considering that the normalization step was not involved in the calculation of RMSE, the accuracy of EMG-force regression in 20% MVC and that in 40% MVC situation were similar and both acceptable. Meanwhile, there was not much performance difference in force regression between the MLR model based on far-field and near-field sEMG. Additionally, representative time series of the ground-truth force and corresponding force trajectories estimated by the MLR models of different fields were shown in Fig. 6.

Exemplary ground-truth force and estimated force trajectories (subject 1, thumb finger, 2nd trial, 40% MVC). The corresponding RMSE values of the near-field and the far-field were 5.46% MVC and 5.92% MVC, respectively.

EMG Decomposition

Estimating discharge patterns of motor units by sEMG decomposition had shown promising perspectives in neurophysiologic investigations and HMI43. Thus, the proposed dataset was also verified from the perspective of neural activity identification, where the source data were the one DoF part (Fig. 1(c)-(iii), finger pressing 1–5) of the finger force dataset. The sEMG decomposition was performed on each electrode, and then the decoding results belonging to the far-field and the near-field were merged separately, which aimed to study the performance difference of different field signal in sEMG decomposition. In this work, the sEMG of a single electrode was decoded by the convolution kernel compensation (CKC) method44. All the decoded MUs of a single electrode were strictly filtered by the following four rules: the coefficient of variation of inter-spike interval45 should be less than 0.45; the average discharging rate should be less than 35 Hz; the pulse-to-noise ratio46 should be larger than 25 dB; the number of spikes should be larger than five times the number of motion seconds. During merging the filtered MUs that belonged to the same field, the ratio of agreement41 between each MUST was calculated to avoid repetition and the threshold was set to 0.3.

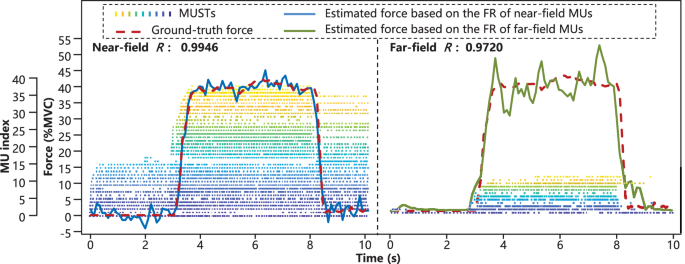

The decomposition results were analyzed from two aspects: one was the total number of MUs, another was the consistence between the ground-truth force and the fitted force based on MUSTs. The fitted force was obtained as follows. Firstly, the firing rate (FR) of each MUST was calculated in each 250 ms window and filtered by an 8-order 10 Hz low-pass Butterworth filter. The slide length between each calculation window was 100 ms. Then, all the processed FRs from one trial were linearly fitted to the ground-truth force, where the optimal fitting parameters were obtained by the least square method. The consistence was evaluated by the Pearson correlation coefficient (R).

The sEMG decomposition results of each subject across all the fingers and trials were outlined in Table 4. In 20% MVC situation, the total average number of decoded MUs and grand average R of near-field were 27.69 and 0.90, while those of far-field were 14.25 and 0.78. In 40% MVC situation, the above values of near-field were 25.31 and 0.90, and those of far-field were 12.70 and 0.79, respectively. Generally, both the number of decoded MUs and the consistence between the ground-truth force and fitted force were acceptable. Compared with far-field, more muscle fibers and neural activities could be identified on near-field, which might be the reason why the fitted force based on near-field produced better accuracy. The number of decoded MUs decreased as the force level increased, which was consistent with existing studies45,46 and might be due to the increased complexity of sEMG caused by the recruitment of extra MUs. In addition, representative time series of the ground-truth and corresponding fitted forces based on MUSTs that were decoded from the sEMG of different fields were presented in Fig. 7.

Exemplary MUSTs, ground-truth force and fitted finger force based on MUSTs. The exemplary data were from subject 1 (thumb finger, 2nd trial, 40% MVC). The corresponding Pearson correlation coefficients of the near-field and far-field were 0.9946 and 0.9720, respectively.

Usage Notes

The proposed HD-FW KIN datasets have great potential usages in the field of naturally controlled prosthetic hands and human-computer interaction of consumer electronics, according to the recognition of human intention. Since our datasets contain 448-channels high-density sEMG signals, it is feasible to observe neural drive from the perspective of MU as well as to develop sophisticated MU decomposition algorithms by using our data. Beyond traditional machine learning and pattern classification methods, our datasets allow for the exploration of proportional control with regard to the continuous angles of fingers, benefitting from the hand kinematics recorded by data-glove.

By including the HD sEMG signals for individual finger and combined multi-finger flexion under different force levels, HD-FW KIN dataset also allows for the advancing research of muscle synergies and unsupervised recognition of multi-finger motions intention. It is important to note that we encourage the usage of HD wrist sEMG to incorporate prior knowledge from the forearm sEMG, since consumer electronics on the wrist are more comfortable and unobtrusive, putting aside the rehabilitation settings. The limitation of this dataset is the absence of dynamic data of wrist movement (gestures 15-20), because the kinematics data were unable to be collected by data-glove. Since the original data has not been processed by known digital filters, the experimental data can also be used to measure the performance of detection digital filters and the noise robustness of algorithms, among other non-conventional usage. However, it is worth noting that when conducting routine electromyographic signal applications, the data should be filtered first.

Responses