Haploinsufficiency of miR-143 and miR-145 reveal targetable dependencies in resistant del(5q) myelodysplastic neoplasm

Introduction

Myelodysplastic neoplasms (MDS) are clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis that lead to bone marrow failure or progression to AML [1,2,3]. MDS is characterized by multiple cytogenetic and molecular defects, which result in an extremely heterogeneous phenotype, making design of molecular-targeted therapies a challenge [4].

Interstitial deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5 is a common genetic aberration seen in MDS [5]. MDS with isolated del(5q) is characterized by macrocytic anemia and hypolobated megakaryocytes [6, 7]. The immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide (LEN) has shown great efficacy in del(5q) MDS patients, leading to improved blood counts and survival [8, 9]. However, 30% to 40% of del(5q) MDS patients are refractory to LEN in the first-line setting, and at least half of primary responders become resistant within two years [8, 10].

LEN functions by Cereblon-mediated CK1α degradation, the protein product of the CSNK1A1 gene [11]. CSNK1A1 is located on the CDR of del(5q) MDS which makes del(5q) cells particularly sensitive to further degradation of the protein by LEN. We and others have shown that LEN-resistance is most frequently associated with loss-of-function mutations in TP53, and we have provided direct evidence that TP53 and RUNX1 mutations inhibit LEN-induced cell death in the context of CSNK1A1 haploinsufficiency [12, 13]. Mutation of either of these two genes inhibits differentiation of del(5q) MDS cells into megakaryocytes, which is required for LEN-induced death of del(5q) cells [13]. miR-143 and miR-145, both located within the CDR, have reduced expression in del(5q) MDS [14, 15]. Deficiency of miR-145 leads to activation of the TGFβ and TIRAP pathways [15,16,17]. However, most experiments have been conducted in mouse models and very little is known about how miR-143/miR-145 haploinsufficiency affects human hematopoiesis.

We hypothesized that haploinsufficiency and subsequent derepression of miR-143/miR-145 targets may support the clonal expansion seen in del(5q) MDS [18, 19]. As miR-143 and miR-145 are transcribed as a single primary miRNA transcript and both of these miRNAs have been characterized as tumor suppressor genes in solid tumors [20], we examined the role of combined haploinsufficiency of these miRNAs in primary human CD34+ cells. In this study, we show that depletion of these two miRNAs results in clonal expansion of human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPC), and that targeting pathways activated by miR-143/miR-145 haploinsufficiency reveals a CK1α-independent vulnerability of del(5q) MDS that remains even when these cells are resistant to LEN. Specifically, we show that IGF-1R signaling is activated with deficiency of miR-143/miR-145 and pharmacologic inhibition of IGF-1R signaling is able to target del(5q) myeloid cells that are resistant to LEN. In addition, we demonstrate that LEN-resistant del(5q) myeloid cells are sensitive to inhibition of pathways regulated by IGF-1R including the Abl and MAPK signaling pathways, providing potential novel therapeutic approaches for del(5q) MDS.

Material and methods

Cell lines, human cord blood cells and patient MDS cells

The leukemic cell lines KG1a, KG1, UT7, K562, U937, and THP1 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The MDS-L cell line, was provided by K. Tohyama (Kawasaki Medical School, Okayama, Japan).

Lentiviral production and transduction

The miR-143/miR-145 decoy was generated by cloning tandem repeats of sequences complementary to miR-143 (MIMAT0000435) and miR-145 (MIMAT0000437) into the 3’UTR of GFP in the lentiviral vector pLL3.7. Mature miRNAs were expressed using the pCCL.PPT.MNDU3.PGK.GFP lentiviral vector [16]. ShRNA (MISSION shRNA, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) were expressed from pLKO.1. VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviral particles (5–10 × 109/ml) were used to transduce purified cord blood CD34+ cells or MDS-L cells as previously described [16].

qRT-PCR

For experiments done with primary human cells, miRNA expression was assayed as previously described [13, 16]. For experiments done with cell lines, miRNA expression was assayed using TaqMan assays with U47 snoRNA as a reference gene, per manufacturer’s directions (assays #002249 (miR-143-3p), #002278 (miR-145-5p), and #001223 (U47), Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Gene expression was analyzed using SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, cat #4368708, Waltham, MA, USA).

Biotin-based RNA pulldown assay

Biotin-based pulldown assays were carried out as previously described (see Supplementary Methods for details) [21, 22].

Luciferase assay

The Dual-Luciferase assay kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, US). Wildtype (WT) and miR-143/miR-145 binding site-mutated IGF-1R 3’-UTR (135 bp) were cloned downstream of a luciferase reporter in the pSGG vector. Reporter constructs along with either vectors overexpressing the miRNAs or empty vector were transfected into HEK293 cells. Luciferase activity was assessed 48 h post-transfection according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunoblotting

Protein lysates were obtained by lysing cells in cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% SDS), in the presence of PMSF, sodium orthovanadate, protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich USA). Immunoblots used the following antibodies: IGF-1R (sc-772; Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), GAPDH (G8795; Sigma-Aldrich).

Growth, survival, and proliferation assays

The IGF-1R small molecule inhibitor BMS-536924 (cat #S1012), Lenalidomide (cat #S1029), Imatinib (cat #S2475), Trametinib (cat #S2673), Temsirolimus (cat #S1044) and Everolimus (cat #sS1120) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA) and resuspended in DMSO. Doses for Imatinib, Trametinib, Temsirolimus and Everolimus were calculated to be similar to serum drug concentrations in patients receiving drug for cancer-related indications [23,24,25,26,27]. MDS-L cell expansion in liquid culture was determined based on manual Trypan blue counts. Annexin V (BD Biosciences, Frank Lakes, NJ, USA) and propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) staining was performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. For BrdU assays, cells were pulsed with 10 mM BrdU for 1.5 h at 37 °C, and then fixed/stained with anti-BrdU antibody according to manufacturer’s instructions (FITC or APC BrdU Flow kit; BD Biosciences USA).

Colony-forming cell (CFC) assays

Clonogenic assays were performed by plating 0.5–1 × 103 /ml human CD34+ HSPC or MDS-L cells in MethoCult H4434 (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada); colonies were scored after 10-14 days. CFC assays colonies were scored as erythroid, myeloid or mixed erythroid-myeloid by morphological criteria; for replating assays, cells were scraped into PBS, then washed and replated into fresh methylcellulose.

Xenotransplantation

All transplants were performed on sublethally irradiated (315 cGy, 137Cs) 8-12-week-old female immunodeficient mice. CD34+ HSPC xenotransplantation was performed by intrafemoral injection of 1–2 ×105 CD34+ cells into NOD/SCID-IL2Rγ (NSG) mice, while MDS-L cells (106) were injected into the tail vein of NOD/Rag1/IL2Rγ (NRG) mice producing human IL-3, GM-CSF, and SCF (NRG-3GS). In vivo delivery of the IGF-1R small molecule inhibitor was performed as previously described [28]. BMS-536924 was dissolved in DMSO (10 mM) and further diluted in 10% solutol (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, US). Animals were injected intraperitoneally with BMS-536924 (40 mg/kg) 3 times weekly starting at 2 weeks post-transplant.

Flow cytometry

Human cell engraftment was monitored by flow cytometry on a FACS Calibur, LSRFortessa or AriaII cell sorter (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) (see Supplementary Methods for details).

IPA and GSEA analysis

Predicted targets of mir-143 and miR-145 from TargetScan (Version 6.2; http://targetscan.org) [29] were subjected to pathway annotation analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software (QIAGEN Bioinformatics)[30]. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was used to analyze published MDS gene expression data for MIR143 and MIR145 expression using the continuous phenotype label method [31, 32].

Sequencing analysis

A target hybridization capture library was constructed and subjected to Illumina sequencing as per routine clinical protocol. The target space includes all recurrently mutated myeloid genes. The generated libraries were aligned against GRCh37 with variants called on samtools mpileup (version 0.1.18) [33], using VarScan2 (version 2.3.6) [34], ONCOCNV (version 6.6) [35], and GenomonSV (version 0.5.0) packages. Variants were manually curated as per ACMG guidelines.

Statistical analysis

All statistics were calculated in Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Results are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was determined using Welch’s t test for unpaired data, with multiple testing correction (Holm-Sidak method) when appropriate. Data from paired samples were compared using the ratio t test. The log-rank (Cox test) was used to compare differences between survival curves. P values below 0.05 and FDR values below 0.25 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Depletion of miR-143 and miR-145 supports clonal expansion of human HSPC

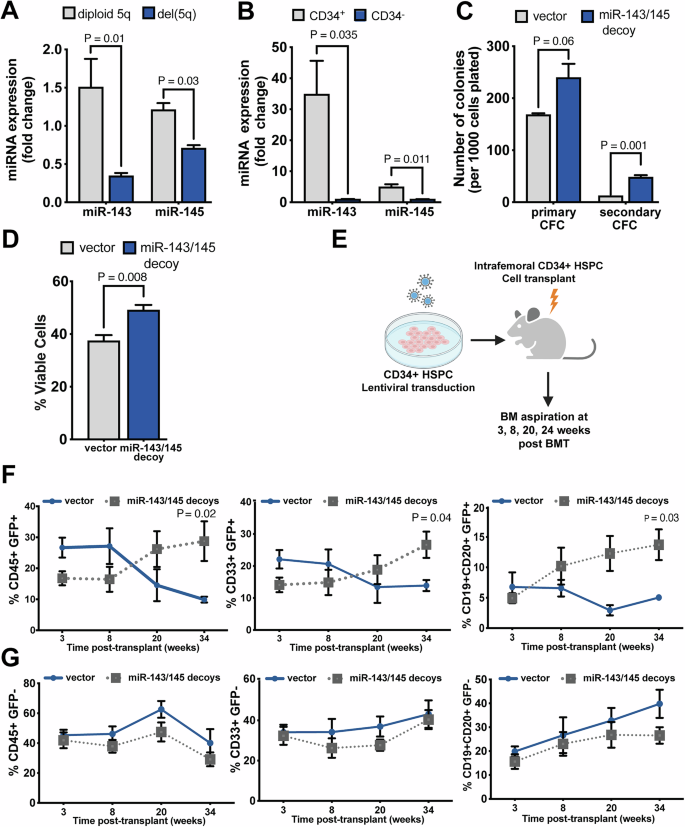

To examine the role of miR-143 and miR-145 in human cells, we first confirmed that their expression was lower in CD34+ cells from del(5q) MDS patient marrow compared to MDS marrow diploid at chromosome 5q, as previously reported [15] (Fig. 1A). Expression of both miRNAs was higher in the CD34+ stem/progenitor cell fraction compared to the more differentiated CD34– cells, suggesting a role for miR-143 and miR-145 in HSPC (Fig. 1B). To model miR-143/miR-145 depletion in human HSPC, we knocked down miRNA expression using lentiviral decoy constructs in CD34+ HSPCs (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). In functional assays for hematopoietic progenitor activity, the miR-143/miR-145 decoy-transduced cells produced more colonies than vector-transduced cells in both primary and serial replating progenitor assays (Fig. 1C). The effect on colony formation was seen in the more-primitive erythroid (BFU-E) with a trend towards an increase in the primitive mix (CFU-GEMM) colonies (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Immunophenotyping of miR-143/miR-145 decoy-transduced CD34+ cells was consistent with the above findings with an increase in total viable decoy-transduced CD34+ cells and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors compared to the control (Supplementary Fig. 1D). Interestingly, there was also an increase in the multipotent progenitor (MPP) fraction. The decoy-transduced cell cultures had enhanced viability, as estimated by Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining (Fig. 1D). Thus, depletion of miR-143 and miR-145 enhances viability of CD34+ HSPC, increases absolute numbers of MPP, and promotes clonogenic potential in vitro.

A Expression of miR-143 and miR-145 measured by qRT-PCR in CD34+ cells from MDS samples with del(5q) or diploid at chromosome 5q (n = 8). B Expression of miR-143 and miR-145 measured by qRT-PCR in CD34+ and CD34− cells isolated from the same cord blood specimens (n = 3). C Primary and secondary CFC assays performed on CD34+ HSPC transduced with miRNA decoys or vector control (n = 3). D Proportion of viable cells at 48 h post-transduction with either miRNA decoys or vector control, as determined by negativity for Annexin V and propidium iodide following in vitro culture of CD34+ HSPC (n = 4). E Schematic of experimental design. CD34+ HSPC transduced with either miR-143/miR-145 decoy or control vectors were injected into sublethally-irradiated NSG mice. At the indicated time points post-transplant, engraftment was measured by flow cytometry of bone marrow aspirates (vector control, n = 3; miR-decoy, n = 6). F, G Engraftment of total human blood cells (human CD45+), myeloid cells (hCD45+CD33+) and lymphoid cells (hCD45+CD19+CD20+) was measured in the G GFP+ (transduced), and the H GFP− (untransduced) fractions.

To determine the impact of miR-143 and miR-145 depletion on hematopoiesis in vivo, we injected CD34+ HSPC, two days post-lentiviral transduction with either the decoy or control vectors, into the femurs of sublethally-irradiated NSG mice. Human lymphomyeloid reconstitution in the marrow of recipient mice was monitored by serial marrow aspiration at weeks 3, 8, 20 and 34 post-transplant (Fig. 1E). Between 8 and 34 weeks post-transplant, decoy-transduced cell populations showed increased marrow chimerism compared to vector-transduced cells (Fig. 1F). This growth advantage included both myeloid and lymphoid GFP+ populations (Fig. 1F), consistent with an increase in MPP. In contrast, the proportions of myeloid and lymphoid cells in the non-transduced (GFP−) human cell compartment in the same mice was similar between the two groups of transplants (Fig. 1G), consistent with miRNA depletion providing a cell intrinsic competitive advantage in vivo. These findings support a role for haploinsufficiency of miR-143 and miR-145 in the clonal expansion of malignant cells in del(5q) MDS.

miR-143 and miR-145 target IGF-1R in human hematopoietic progenitor cells

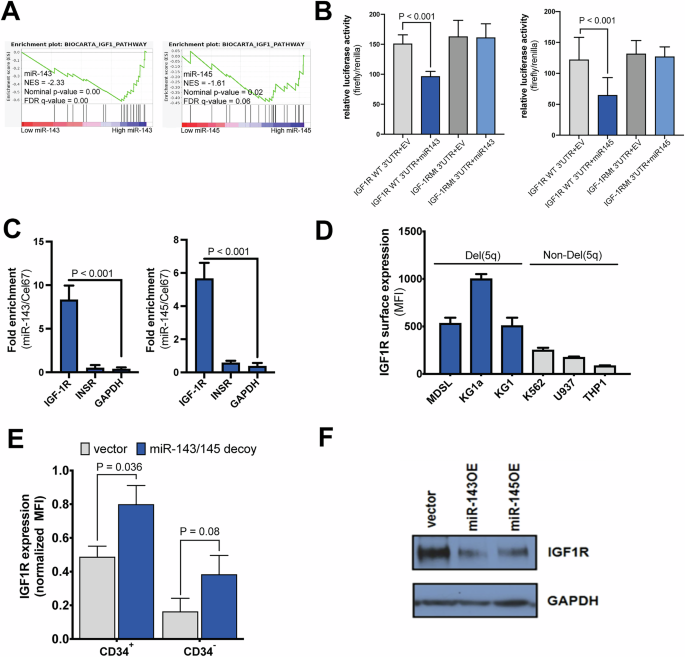

We have previously determined which pathways are targeted by both miRNAs using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) [30] on the non-redundant set of predicted targets of miR-143 and miR-145 [16]. Here we used gene expression data from a previously-published cohort of MDS patients [36], ranked samples on the basis of either the expression of miR-143 or the expression of miR-145, and performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [31] to determine which BIOCARTA pathways were differentially upregulated with low expression of miR-143 and miR-145 (Supplementary Table 1). The IGF-1 signaling pathway was the only pathway common to both analyses (Fig. 2A). In addition, the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) was predicted to be a target of both miR-143 and miR-145 based on the miRNA-target prediction algorithm, TargetScan (Supplementary Table 2) [37].

A GSEA enrichment plots for the IGF1 pathway based on either miR-143 or miR-145 expression. Descriptive statistics from GSEA are shown: NES normalized enrichment score; NOM p-value, nominal p-value; FDR, false discovery rate. B Luciferase activity of cells transfected with either WT or mutated IGF-1R 3’UTR along with miR-143 or miR-145 (n = 3). C qRT-PCR following miR-143 or miR-145 pulldown in MDS-L cells after transfection with Biotin-miR-143 or Biotin-miR-145 (n = 8). D Cell surface expression of IGF-1R using flow cytometry of myeloid cell lines with del(5q) or diploid at chromosome 5q (performed in triplicate for each cell line). E Normalized total IGF-1R expression in CD34+ and CD34– cord blood cells transduced with miR-143/miR-145 decoy or control vector (n = 6). F Western blot for IGF-1R and GAPDH as a loading control in the del(5q) cell line MDS-L following lentiviral expression of miR-143 (miR-143OE), miR-145 (miR-145OE), or a vector containing a non-targeting sequence.

To validate the predicted interaction between miR-143/miR-145 and the 3’-UTR of IGF-1R mRNA, we performed luciferase assays using the wildtype (WT) or mutated IGF-1R 3’UTR containing mutations in the predicted binding sites, cloned downstream of a luciferase reporter. Overexpression of miR-143 or miR-145 markedly reduced luciferase activity in cells with the WT IGF-1R 3’UTR but not the mutated IGF-1R 3’UTR (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, an miRNA pulldown assay demonstrated that biotinylated miR-143 and miR-145 transfected into del(5q) MDS-L cells directly bound to IGF-1R mRNA, but not to insulin receptor (INSR) mRNA, confirming the specificity of the interaction (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). In addition, surface expression of IGF-1R was higher in del(5q) myeloid cell lines compared to myeloid cell lines diploid for chromosome 5q (Fig. 2D). To confirm that the miR-143/145-IGF-1R interaction is functionally relevant in primary hematopoietic cells, we transduced CD34+ HSPC with control or miRNA-decoy vectors. Surface IGF-1R expression was increased in miRNA-decoy cells, particularly in the CD34+ HSPC fraction compared to the differentiated CD34– cells (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, MDS-L cells transduced with the miR-143/145 decoy showed elevated responses to IGF1 as determined by phosphorylation of IGF-1R, AKT and MAPK (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Stimulation of primary CD34+ cells with IGF-1 (10 ng/mL) resulted in increased total colonies in serial CFC assays (Supplementary Fig. 2D, E), as seen with miR143/145 depletion.

Conversely, overexpression of each of the miRNAs in the MDS-L del(5q) cell line led to decreased protein expression of IGF-1R (Fig. 2F). MDS-L cells overexpressing either miRNA had reduced colony formation in CFC assays, as well as reduced proliferation and a trend towards reduced viability (Supplementary Fig. 3). These data suggest that miR-143 and miR-145 regulate cell progenitor activity and cell proliferation in primitive human hematopoietic cells through the regulation of IGF-1R expression.

IGF-1R inhibition reduces progenitor activity of miR-143/miR-145-haplodeficient del(5q) cells

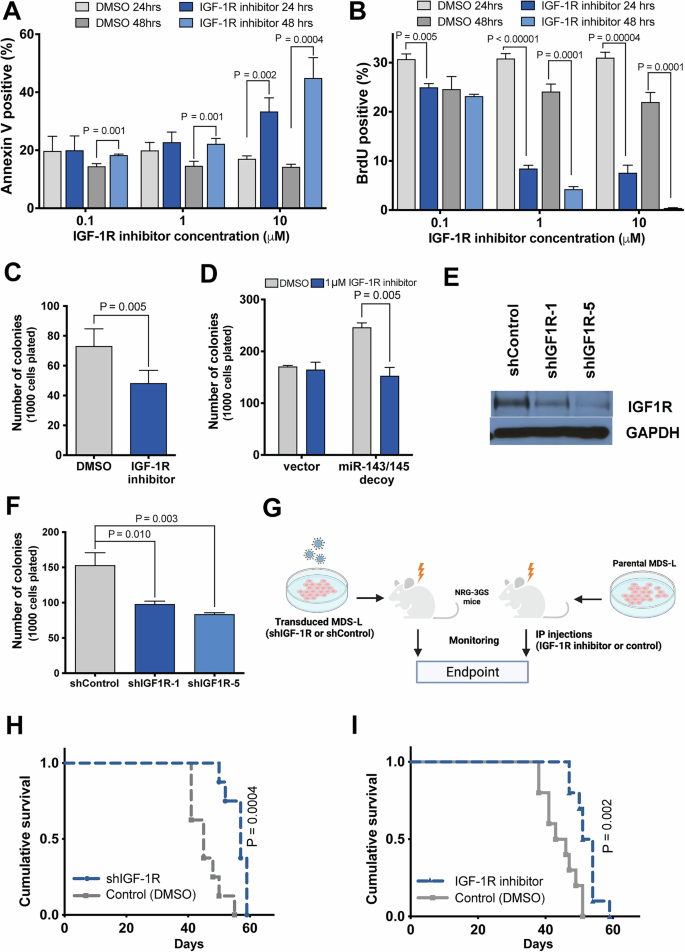

To determine which effects of miR-143/miR-145 deficiency are mediated by IGF-1R, we first asked whether specific inhibition of IGF-1R signaling in del(5q) MDS-L cells could abrogate cell expansion in vitro. To address this, we treated MDS-L cells with a small molecule IGF-1R inhibitor, BMS-536924, at various concentrations. At all tested doses of the inhibitor, there was a significant increase in cell death by 48 h of treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4A, Fig. 3A). Proliferation was also significantly reduced, in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). Cells treated with inhibitor appeared to mainly target cycling cells as cells were less likely to be in S-phase with more cells in G0/G1 of the cell cycle compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 4B). At the highest dose, cells were virtually eliminated following 3 days of treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5). Consistent with the above, MDS-L cells pre-treated with an intermediate concentration (1 μM) of IGF-1R inhibitor for 48 h had reduced output in CFC assays (Fig. 3C).

A Effect of IGF-1R inhibition on MDS-L cell survival, as measured by Annexin V staining (n = 4). B Effect of IGF-1R inhibition on MDS-L cell proliferation, as measured by BrdU incorporation (n = 4). C Colony forming activity of MDS-L cells treated with IGF-1R inhibitor or vehicle (DMSO) (n = 4). D Progenitor activity, as measured by CFC assay, of CD34+ HSPC depleted of miR-143/miR-145 using a decoy vector or control vector, and treated with IGF-1R inhibitor (BMS-536924, 1 μM) or vehicle (DMSO) (n = 3). E Western blot for IGF-1R, and GAPDH as a loading control, in shIGF-1R-transduced or shControl-transduced MDS-L cells. F Colony-forming activity of shIGF-1R-transduced MDS-L cells in semisolid medium (n = 6). G Schematic of experimental design. On the left, NRG-3GS mice were sublethally irradiated, then transplanted with MDS-L cells transduced with either shIGF-1R or shControl. On the right, NRG-3GS mice were sublethally irradiated, then transplanted with parental MDS-L cells that were allowed to engraft for 2 weeks prior to beginning intraperitoneal injections with either inhibitor (BMS-536924, 40 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle (2.5% DMSO:10% Solutol v/v) three times a week. H Survival curves of mice engrafted with MDS-L cells transduced with shIGF-1R or control vector (n = 8). I Survival curves of mice treated with IGF-1R inhibitor or vehicle (control n = 9; IGFR1 inhibitor n = 10).

To extend this result to primary cells, CD34+ HSPC were transduced with either miRNA-decoy or control vector, treated with BMS-536924 (1 μM) and subjected to CFC assays. As observed previously, miRNA-decoy-transduced cells had increased colony output (Figs. 2E and 3D). However, IGF-1R inhibition reduced colony formation only in decoy-transduced cells, but had no effect on vector-transduced cells (Fig. 3D), potentially implicating a differential effect in del(5q) MDS cells compared to normal cells. Next, we used a complementary genetic approach, by targeting IGF-1R through lentiviral-delivered shRNA to reduce its expression in the del(5q) MDS-L cell line. Knockdown of IGF-1R resulted in reduced IGF-1R protein expression compared to the control shRNA-transduced cells (Fig. 3E). Cells transduced with shIGF-1R had reduced colony formation in clonogenic assays compared to controls (Fig. 3F). Together, these studies suggest that pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of IGF-1R signaling reduces cell expansion observed with loss of miR-143 and miR-145, consistent with the hypothesis that derepression of IGF-1R is functionally relevant in human del(5q) MDS.

To determine whether targeting IGF-1R would prolong survival in mice xenografted with human del(5q) MDS-L cells, we used a xenograft model in which NRG-3GS immunodeficient mice expressing three human growth factors were transplanted with MDS-L cells. To determine the specific effect of IGF-1R depletion in this model, we transplanted MDS-L cells transduced with shIGF-1R or shControl into NRG-3GS mice. Depletion of IGF-1R resulted in significantly prolonged survival of xenografted mice compared to the controls (median survival 57 days vs. 45 days, P = 0.0004) (Fig. 3H). To confirm that pharmacological inhibition of IGF-1R would have the same effect, we xenografted parental MDS-L cells into NRG-3GS mice, and injected engrafted mice intraperitoneally with BMS-536924 (40 mg/kg) 3 times weekly starting at 2 weeks post-transplant. As with IGF-1R knockdown, chemical inhibition of IGF-1R resulted in significant improvement in median survival, compared to controls (52 days vs 44 days, P = 0.0016) (Fig. 3I). Thus, either genetic knockdown or pharmacologic inhibition of IGF-1R inhibits the expansion of del(5q) MDS-L cells in a preclinical model of haploinsufficiency for miR-143 and miR-145.

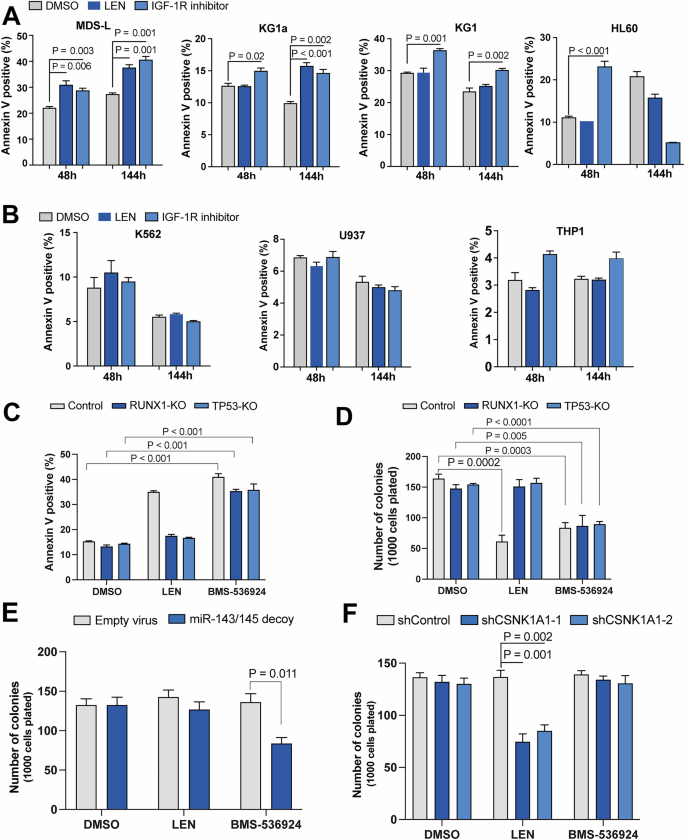

IGF-1R inhibition bypasses LEN resistance in del(5q) MDS cells

Given that a significant proportion of del(5q) MDS patients do not respond to LEN or become resistant over time, we attempted to determine whether IGF-1R might be a relevant target in LEN-resistant del(5q) cells. To address this, we examined the efficacy of IGF-1R inhibitor, BMS-536924, along with LEN on four del(5q) and three non-del(5q) myeloid cell lines by measuring apoptosis and proliferation. Targeting IGF-1R reduced the viability of all del(5q) cell lines (Fig. 4A), including those known to be resistant to LEN (KG1, HL60) [38]. HL60 cells were mostly eliminated prior to the 144 h time point with remaining cells likely resistant to IGF-1R inhibitor. In contrast, survival of non-del(5q) cell lines was not affected by the addition of BMS-536924 (Fig. 4B). We further assessed the effect of BMS-536924 on three del(5q) MDS patient samples, and found that inhibition of IGF-1R signaling suppressed colony formation in these primary MDS patient samples (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Apoptosis was measured by Annexin V labeling, at 48 and 144 h of culture in the presence of vehicle (DMSO), LEN (1 μM) or IGF-1R inhibitor (BMS-536924, 1 μM) in del(5q) cells (A) and diploid chromosome 5q cells (B). C LEN-resistant MDS-L cells that were knocked out (KO) for TP53 or RUNX1 along with WT MDS-L cells were treated with LEN (1 μM) or IGF-1R inhibitor (BMS-536924, 1 μM) and apoptosis was measured by Annexin V staining. D Colony forming activity of LEN-resistant MDS-L cells following treatment with LEN (1 μM) or IGF-1R inhibitor (BMS-536924, 1 μM). E Colony output of OCI-AML3 cells (diploid for chromosome 5q) transduced with miR-143/miR-145 decoy was measured in the presence of LEN (1 μM) or IGF1-R inhibitor(BMS-536924, 1 μM). F Clonogenic activity of OCI-AML3 cells transduced with shCSNK1A1 constructs was examined in the presence of LEN (1 μM) or IGF-1R inhibitor (BMS-536924, 1 μM).

We have previously shown that loss of function mutations in TP53 or RUNX1 cause LEN resistance [13]. To further assess the efficacy of IGF-1R inhibition in the context of LEN resistance we used CRISPR/Cas9 MDS-L cells targeted for TP53 or RUNX1 that are resistant to LEN [13]. Despite LEN resistance, BMS-536924 caused significant cell death and reduced the clonogenic output of TP53- or RUNX1-targeted MDS-L cells (Fig. 4C, D). CSNK1A1 haploinsufficiency is required for LEN-induced cell death in del(5q) MDS cells [11]. As miR-143/miR-145 function is likely independent of CSNK1A1, we sought to determine if IGF-1R inhibition is effective via a pathway that is distinct from LEN by using the OCI-AML3 cell line that expresses diploid copies of CSNK1A1, miR-143 and miR-145. The OCI-AML3 cell line was transduced with the miR-143/miR-145 decoy construct or empty vector, or shRNAs against CSNK1A1 or a control shRNA, and colony output of these cells was measured in the presence of either LEN, BMS-536924, or vehicle (Supplementary Fig. 7). miR-143/miR-145 decoy-transduced cells had decreased clonogenic output with BMS-536924 treatment while LEN had no effect (Fig. 4E). In contrast, cells transduced with shCSNK1A1, had reduced colony number with LEN treatment but BMS-536924 had no effect (Fig. 4F). These results verify that IGF-1R inhibition acts via a mechanism distinct from LEN/CK1α to suppress del(5q) MDS cells.

Del(5q) MDS cells targeting TP53 or RUNX1 are sensitive to Abl or MAPK inhibitors

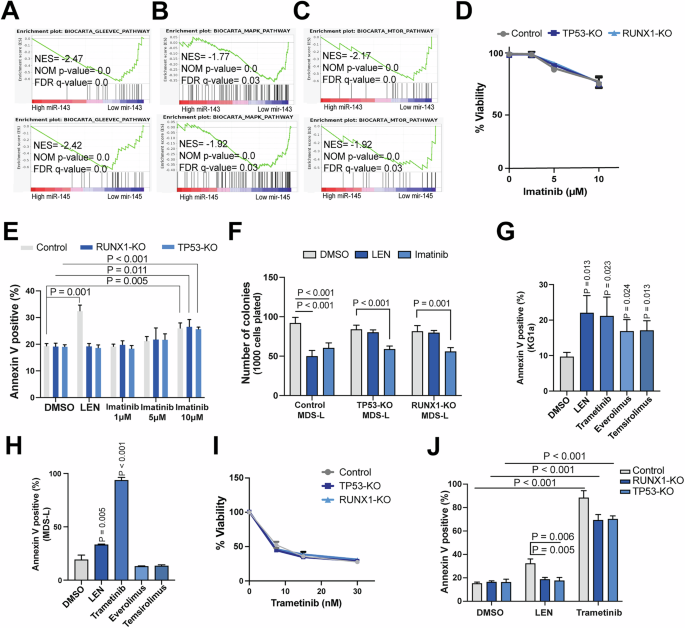

IGF-1R is frequently overexpressed in different cancers, but results of clinical trials with IGF-1 or IGF-1R have not shown convincing efficacy, resulting in the lack of further development of these compounds [39,40,41]. We thus sought to determine whether targeting IGF-1R-related pathways also exposed vulnerabilities in del(5q) MDS cells. Abl is involved in autoregulation of IGF-1R activity [42, 43]. Interestingly, our GSEA analysis showed the BIOCARTA_GLEEVEC geneset, containing genes involved in Abl signaling, to be the top differentially upregulated pathway in MDS patients with low miR-143 or miR-145 (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 5A). We also examined whether other pathways downstream of IGF-1R were differentially upregulated with miR-143 and miR-145 haploinsufficiency. We performed GSEA analysis on previously published RNA expression data of MDS samples [36], and showed the BIOCARTA_MAPK and BIOCARTA_MTOR pathways to both be significantly activated in patients with low expression of either miR-143 or miR-145 (Fig. 5B, C). In contrast, the PI3K/Akt pathway was not activated with low expression of miR-143/miR-145 (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results suggest that the Abl, MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways may provide a potential therapeutic target for LEN-resistant del(5q) MDS.

GSEA enrichment plots based on miR-143 or miR-145 expression for the BIOCARTA_GLEEVEC (A), BIOCARTA_MAPK (B), and BIOCARTA_MTOR (C) pathways in MDS patient CD34+ bone marrow cells. D Imatinib dose-response curves for LEN-resistant and WT MDS-L cells following treatment for 48 h, as measured by AlamarBlue assay. E Proportion of apoptotic cells as measured by Annexin V staining for LEN-resistant and WT MDS-L cells following 144 h treatment with imatinib, LEN or vehicle (DMSO). F Colony output of LEN-resistant and WT MDS-L cells in the presence of imatinib (10 μM), LEN (1 μM) or vehicle (DMSO). Effect of inhibitors of pathways downstream of IGF-1R including everolimus (mTOR inhibitor, 0.1 μM), temsirolimus (mTOR inhibitor, 0.5 μM) and trametinib (MEK1/2 inhibitor, 0.03 μM) or LEN (1 μM) or vehicle (DMSO), on del(5q) cell lines: KG1a cells (G) and MDS-L (H). I Trametinib dose-response curves for LEN-resistant and WT MDS-L cells following treatment for 48 h, as measured by AlamarBlue assay. J Proportion of apoptotic cells as measured by Annexin V staining for LEN-resistant and WT MDS-L cells following 144 h treatment with trametinib (0.03 μM), LEN (1 μM) or vehicle (DMSO).

Given that Abl, MAPK and MTOR signaling pathways were differentially upregulated with low expression of miR-143/miR-145, we sought to determine the dependency of del(5q) cells on these pathways. The Abl inhibitor, imatinib, reduced the viability and colony output of LEN-resistant MDS-L cells (Fig. 5D–F). Additionally, we assessed the effect of FDA approved inhibitors of MAPK and MTOR signaling pathways. Trametinib (MEK1/2 inhibitor), everolimus and temsirolimus (mTOR inhibitors) reduced the viability of del(5q) KG1a cells significantly (Fig. 5G), but only trametinib induced significant cell death in MDS-L cells (Fig. 5H). As trametinib was the only effective inhibitor in both del(5q) cell lines, we evaluated the sensitivity of LEN-resistant MDS-L cells to this inhibitor. Trametinib treatment resulted in reduced viability of LEN-resistant MDS-L cells, similar to wild-type control cells, in cells deficient for either TP53 or RUNX1 (Fig. 5I, J).

LEN-resistant del(5q) MDS patients cells are sensitive to inhibition of Abl or MAPK pathways

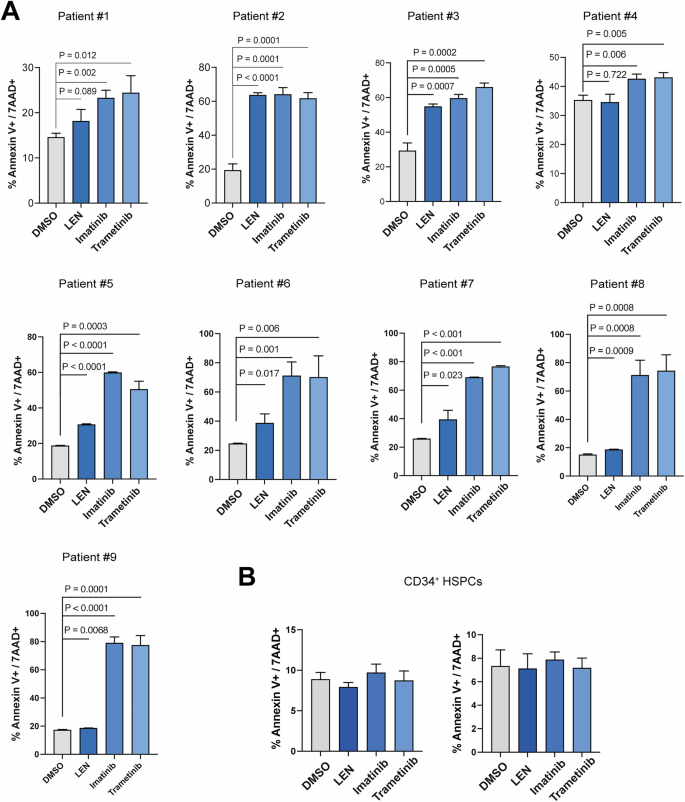

To further validate our findings, we assessed the efficacy of trametinib on ex vivo cultured cells from del(5q) MDS patients that were either sensitive or resistant to LEN. Mutational analysis on these nine del(5q) MDS patient samples identified pathogenic variants of TP53 in one sample (Supplementary Table 3). All samples regardless of their sensitivity to LEN were sensitive to both imatinib and trametinib (Fig. 6A), while CD34+ HSPC were not sensitive to the tested inhibitors (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that targeting Abl or MAPK signaling pathways holds therapeutic promise for LEN-resistant del(5q) MDS patients.

Viability of bone marrow cells from del(5q) MDS patients (A), or normal CD34+ HSPC (B), following treatment with Imatinib (10 μM), Trametinib (0.015 μM), LEN (1 μM), or vehicle (DMSO) for 48 h, as measured by Annexin V/7AAD staining.

Discussion

We and others have previously shown that the del(5q) MDS phenotype is partially mediated by miRNA haploinsufficiency in mouse models [14,15,16]. Here, we identify activation of the IGF-1R pathway as a consequence of depletion of miR-143 and miR-145 in human hematopoietic cells. We confirmed that IGF-1R is a direct target of both miR-143 and miR-145 using luciferase and RNA pulldown assays. With three lines of evidence – IGF-1R knockdown by shRNA, IGF-1R depletion by overexpression of miR-143 and/or miR-145, and chemical inhibition of IGF-1R we demonstrate that targeting IGF-1R results in reduced viability, proliferation and colony output. In complementary experiments, we show both in vitro and in vivo that depletion of miR-143 and miR-145 results in derepression of IGF-1R signaling and clonal expansion, and further that inhibition of IGF-1R rescues the phenotype of miRNA depletion in functional assays. We further provide evidence that IGF-1R inhibition is able to bypass LEN-resistance. Importantly, our data identify two FDA-approved drugs that interact with the IGF-1R signaling pathway, namely Abl kinase AND MEK inhibitors, that could be repurposed for LEN-resistant del(5q) MDS.

IGF-1 signaling has been reported to play a role in growth and self-renewal of both hematopoietic and embryonic stem cells. IGF-1 signaling also contributes to progression of several cancers including AML and MDS [39, 44, 45], and bone marrow cells of some MDS patients overexpress IGF-1R compared to normal bone marrow cells [44]. Although various IGF1/IGF-1R inhibitors have undergone clinical trials in solid tumors, these trials did not examine potential biomarkers to identify susceptible cases, and this may have been the reason for the failure of these trials [41, 46].

The IGF-1 signaling pathway involves a complex network that is regulated at multiple levels. In particular, Abl and IGF-1R are involved in an autocrine signaling loop [42, 43]. GSEA analysis revealed that genes of the Abl signaling pathway (BIOCARTA_GLEEVEC) are activated with deficiency of miR-143 and miR-145. Signals secondary to IGF-1R signaling are also activated in many cancers including acute lymphoblastic leukemia, breast and prostate cancers, and act to promote tumor cell viability and proliferation [46,47,48,49]. Our analysis demonstrated that MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways which act downstream of IGF-1R are activated in MDS samples with low expression of miR-143 and miR-145. Importantly, we show that LEN-resistant del(5q) cells are sensitive to either imatinib or trametinib, FDA-approved inhibitors of Abl and MAPK pathways, respectively. In contrast, mTOR inhibitors while effective in one del(5q) cell line, were not able to kill a second del(5q) cell line. Activation of the MAPK pathway is documented to be involved in progression and drug resistance of many cancers including AML and MDS, which has encouraged preclinical and clinical trials [50,51,52,53,54,55]. Here we show that both imatinib and trametinib are able to reduce the viability of LEN resistant MDS-L cells and primary MDS samples.

Interestingly, LEN resistance is most frequently secondary to mutations in TP53 and RUNX1 [13] which are challenging to target. Given the limited success of recent trials targeting TP53 [56, 57], therapies focusing on alternative approaches may offer promising strategies to overcome resistance. That inhibition of IGF1R, Abl or MEK is able to kill MDS cells harboring these mutations is of great interest. Findings from this manuscript suggest that miR-143/145 loss activates the IGF1R pathway in del(5q) MDS, and this activation leads to critical survival signals in this disease. MAPK acts a survival signal downstream of IGF1R, as has been reported in other instances [58]. In the case of del(5q) MDS, IGF1R/Abl/MEK signaling appears to be a key cell survival strategy regardless of additional mutations that may be present. Our findings suggest that inhibiting this pathway exposes a vulnerability of del(5q) MDS cells rather than specific targeting of TP53 or RUNX1 mutations. As such, targeting other dependencies in the context of TP53 or RUNX1 mutations may be a viable alternate strategy in these difficult to treat myeloid malignancies.

Haploinsufficiency of CSKN1A1 in MDS cells with del(5q) renders these cells sensitive to LEN [11, 13]. We demonstrated that sensitivity of del(5q) MDS cells to inhibition of IGF-1R, MAPK and Abl signaling are dependent on haploinsufficiency of miR-143/miR-145 and independent of CSNK1A1 haploinsufficiency, implicating a novel parallel dependency in del(5q) MDS cells. Our findings suggest that targeting Abl and MAPK signaling pathways by repurposing FDA-approved drugs may be a novel therapeutic option for LEN-resistant MDS.

Overall, our findings suggest two distinct, coexisting vulnerabilities in del(5q) MDS, both of which target haploinsufficiency of genes within the CDR of del(5q). Haploinsufficiency of CSKN1A1 in MDS cells with del(5q) renders these cells sensitive to lenalidomide. In contrast sensitivity to IGF-1R inhibition in del(5q) MDS cells is secondary to haploinsufficiency of miR-143 and miR-145. Our finding that lenalidomide-resistant del(5q) MDS cell lines are sensitive to IGF-1R, ABL or MEK inhibition provides alternative approaches, through a coexisting but independent vulnerability, for therapeutic trials in del(5q) MDS patients who are resistant to lenalidomide.

Responses