Harmonizing cross-cultural and transdiagnostic assessment of social cognition by expert panel consensus

Introduction

Social-cognitive deficits and biases are common among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders1,2,3,4,5. These difficulties are related to various negative functional outcomes such as poorer community functioning, underdeveloped social skills, and less effective social problem-solving6. Recently, two important expert reviews supported a key role of social cognition in the assessment and treatment of psychosis. First, the consensus statement from a group of world leading researchers and clinicians identified social cognition as one of the domains that is crucial for precise clinical characterization and treatment planning for individuals with schizophrenia7. In addition, the schizophrenia section of the European Psychiatric Association also recently formulated a guidance paper with recommendations for optimal assessment of, among others, social cognition8. In their paper, they recommend assessment of social cognition mainly for the characterization of patients, as well as for personalized treatment planning.

Despite these calls for the routine assessment of social cognition, measurement continues to be a significant challenge, particularly regarding which constructs to consider and how to best measure them9. Many social cognition tasks were originally developed in the context of autism spectrum disorder research (involving false beliefs and verbal/visual mentalizing tasks) but subsequent research has demonstrated that these tasks show poor psychometric properties and/or construct validity in adult populations (e.g.,10,11). Likewise, assessments derived from social neuroscience studies in healthy adults have also shown relatively weak psychometric properties in schizophrenia12. Most notably, the Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation project (SCOPE13,14), a NIMH-funded, multi-round study focusing on the identification of sound social cognitive measures for use in clinical trials of schizophrenia, identified just three measures with sufficient psychometric properties that could be recommended for further use: the Hinting Task15, the Penn Emotion Recognition Task (ER-40)16, and the Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (BLERT)17.

While the SCOPE recommended tasks have been heavily used in the United States and United Kingdom, two of them show limited utility for large-scale international trials. The Hinting Task, for example, is a verbal task strongly influenced by social norms and knowledge, with vignettes that may not be applicable across cultures18. The BLERT utilizes low-quality videos of a single white male depicting various emotions that may not accurately represent diverse cultural contexts, particularly in light of the well-established other-race effect, which is also evident among individuals with schizophrenia and which may contribute to poorer performance in non-white individuals19. As these examples demonstrate, the role of culture in social cognitive performance is well established20, and thus individuals may appear to have more impaired social cognitive functioning when tasks are not matched to culture. Although SCOPE did not consider cross-cultural applicability in its evaluation criteria, the results underscore both the paucity of high-quality social cognitive tasks as well as the broad lack of tasks that can be used cross-culturally. The need for culturally sensitive social cognitive assessments has long been emphasized8,21,22, and the unavailability of such tasks renders harmonization efforts impossible.

In addition, interest in understanding social cognitive impairments is not limited to schizophrenia spectrum illnesses. Social cognition is adversely affected in numerous psychiatric (e.g., bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa), neurological (e.g., traumatic brain injury, stroke, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease), and neurodevelopmental conditions (e.g., Autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)23,24. By and large, these impairments are of moderate to large effect sizes and in many cases exceed the magnitude of other cognitive impairments that are also seen in these conditions. As such, experts are increasingly calling for the incorporation of social cognitive assessment into clinical practice and note that patterns of social cognitive impairment may inform differential diagnosis (e.g., parsing frontotemporal dementia from primary psychiatric disorder) and disease progression25. Harmonization efforts such as these require measures that can be utilized transdiagnostically, in which task psychometric properties remain similar across different clinical groups and meaningful comparisons between clinical groups can be made. Successful identification of such tasks would facilitate efforts to examine the possibility of shared vs. distinct etiologies of social cognitive impairments across disorders and to identify disorder specific difficulties that would inform clinical decisions and treatment planning.

To address these measurement limitations and challenges within social cognitive research, a group of experts was convened to form the Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) Social Cognition Research Harmonization Group (RHG). The goals of the RHG were twofold: (1) conduct a wide-ranging expert survey to gather nominations for tasks of social cognition that may be well-suited to cross-cultural and transdiagnostic use among adults, and (2) use the Delphi Method within our RHG to identify a consensus set of social cognitive measures from these nominations for use in future data collection. Although cross-cultural and transdiagnostic applicability are separate concepts and usually examined individually, the current study sought to leverage the expertise of the field and the RHG to advance social cognitive assessment on both fronts. In doing so, it was also hoped that some tasks would be identified as suitable for both cross-cultural and transdiagnosic use, which could provide an immediate foundation for collaborative projects. This paper reports the outcomes of these efforts.

Results

Expert survey

Fifty-two tasks were nominated for cross-cultural use, and 77 tasks were nominated for transdiagnostic use. Forty-seven tasks were nominated as potentially suitable for use pending further development. Many tasks were nominated across uses, resulting in a total of 81 unique tasks across all categories. These tasks are listed alphabetically in Table 1.

Delphi Round 1

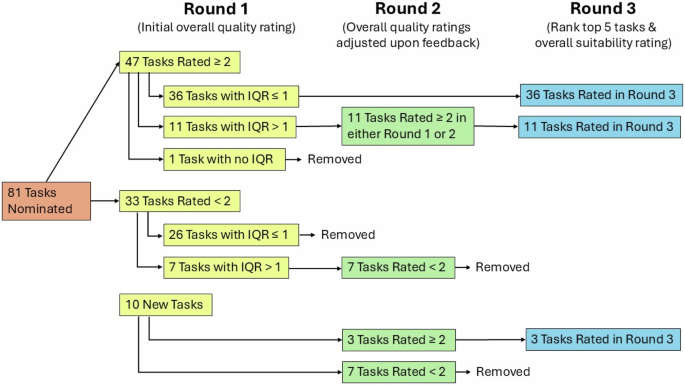

Twenty-one members of the RHG provided complete ratings for each of the 81 tasks. Forty-seven tasks received mean ratings ≥2 (adequate or better). Eleven of these tasks had an IQR > 1 and were included in Round 2. The remaining 36 tasks receiving consensus ratings of ≥2 were retained for further evaluation in Round 3. Thirty-three tasks scored in the inadequate range, and of these, 26 had consensus average ratings of <2 (i.e., average score of <2 and IQR of ≤1) and were therefore removed from further consideration. The remaining 7 were carried forward to Round 2. IQR could not be calculated for one task due to the lack of non-zero scores, and this task was also omitted from further consideration. Average Round 1 ratings and IQR values for each task are provided in Table 1.

During this round, 10 additional tasks were also nominated, resulting in 28 tasks that still required consensus ratings and a total of 64 tasks remaining under consideration. New tasks are listed at the bottom of Table 1, and a flow chart of the complete rating process is depicted in Fig. 1.

Flow Chart of the Delphi Rating Process.

Delphi Round 2

Seventeen members of the RHG provided complete ratings. Consensus was reached for 16 of the original tasks and 8 of the additional tasks, resulting in 4 tasks for which consensus was not reached. In either Round 1 or 2, 50 tasks received ratings of ≥2 indicating “adequate” or better quality, and these tasks advanced to Round 3. Tasks that failed to achieve a rating of 2 or more in either Round 1 or 2 were dropped from consideration (n = 14). Average ratings and IQR values from Round 2 are presented in Table 1.

Delphi Round 3

For this round, tasks were categorized according to social cognitive domain, and tasks assessing multiple domains (e.g., OSCARS) were listed within each applicable domain. This process resulted in 23 tasks for emotion processing, 6 for social perception, 17 for mental state attribution, 4 for attributional style/bias, and 6 for empathy.

Eighteen members of the RHG provided task rankings and ratings for suitability of use. Within each domain, a top tier of tasks emerged as the most consistently selected, and all were rated as having “good” or better suitability for use. The top six ranked tasks for cross-cultural use are listed in Table 2, and the top six ranked tasks for transdiagnostic use are listed in Table 3. Average suitability ratings for these tasks are also presented in the corresponding tables. Information for the remaining emotion processing and mental state attribution tasks are provided in Supplementary Tables 3, 4.

Discussion

The current study utilized an expert survey and Delphi consensus process to identify social cognitive tasks that may be appropriate for cross-cultural and/or transdiagnostic use. Within the domain of emotion processing, the ER-40 ranked as the top task for both cross-cultural and transdiagnostic use. This task shows 40 static images of individual’s faces and asks participants to label the emotion shown from the following choices: happy, sad, anger, fear, no emotion. The ER-40 uses age, gender, and ethnically diverse stimuli and has minimal verbal demand, which likely contributed to its high ranking.

Far fewer tasks assessing social perception were available; however, the OSCARS emerged as the most promising for cross-cultural use and the second most promising for transdiagnostic use. The OSCARS can be used as a self- and/or informant-report assessment and asks how much difficulty someone has decoding verbal cues. While an early study indicated that informant reports showed stronger convergent and external validity than self-reports26, a more recent, larger study suggests equivalent validity between the two modalities27. The interview-based format provides the option to combine across sources of information, including self- and informant-report or multiple informants, and may provide a more sensitive indicator of real-world change than performance-based tasks, thus potentially serving as a valuable coprimary measure for clinical trials28. Translation of this task is likely necessary for cross-cultural use; however, the general, non-performance based assessment approach may make it widely applicable and more easily adaptable to other cultures.

Several tasks evaluating mental state attribution were nominated, with both the SAT-MC and TASIT being ranked highest for cross-cultural use and the TASIT ranked highest for transdiagnostic use. The SAT-MC shows short animations of geometrical shapes enacting a social drama, and participants answer multiple choice questions about the actions and intentions of the shapes. The minimal verbal and memory demands of this task make it highly feasible for both uses, and it is noteworthy that it has one of the highest suitability ratings of all tasks for cross-cultural use. The TASIT involves short videos of everyday social interactions involving two or more people and evaluates the ability to detect lies and sarcasm in these interactions. The videos include English-speaking actors with Australian accents, which may somewhat limit its cross-cultural applicability; however, this should not impede transdiagnostic use, and an abbreviated format and some translations are available (e.g.,29,30).

For attributional style/bias, the AIHQ received the highest rankings for both uses. This task presents hypothetical, negative situations with ambiguous causes and asks participants why the scenario occurred. Participants also rate whether the other person acted intentionally, how angry it would make them feel, and how much they would blame the other person. Finally, they are asked how they would respond to the situation. The high ranking of this task for cross-cultural use is somewhat surprising given the high dependence on verbal language; however, the situations used are likely to be considered negative and ambiguous across most cultures, which may explain its high ranking. Further, only four tasks were nominated in this category, and the modest suitability ranking for cross-cultural use, as compared to transdiagnostic use, likely reflects some hesitancy regarding the task.

Finally, within the domain of empathy, the QCAE was highly ranked for both uses. This self-report scale asks participants to rate how much statements pertaining to cognitive and affective empathy pertain to them. Importantly, despite being ranked highly, suitability ratings for this task were modest, again suggesting that while it is a “good” task, additional development would be needed for optimal use.

Overall, there was considerable overlap in the top ranked tasks within each domain for cross-cultural and transdiagnostic use. This may be due to the somewhat limited number of generally “good” tasks from which to choose or to the possibility that the same characteristics make a task appealing for either transdiagnostic or cross-cultural use (e.g., sound basic psychometrics like validity and reliability). Nevertheless, there were a few instances, for example the Hinting Task, in which a task was ranked highly for one use and not another. Thus, we suggest care when selecting tasks for each potential use.

Additionally, while these measures, and others, exhibited potential and were rated relatively favorably, no task emerged as ideally suited for the intended use. Of tasks considered in Round 3, suitability ratings were primarily in the “good” range, with no tasks scoring in the highest range, and from Rounds 1 and 2, almost half of the tasks received ratings in the inadequate range. This may be because very few social cognitive tasks have been specifically designed with cross-cultural considerations in mind. As excellently reviewed by Bourdage and colleagues31 who focused on tasks appropriate for Global South communities, there is a considerable lack of multicultural assessment tools, and attempts to modify existing tasks have been primarily of low quality. Further, many existing modifications have been conducted with a single culture in mind (i.e., translating a measure to be used in a specific location) rather than with the goal of making a truly cross-cultural tool that could be readily used across several cultures.

It is also noteworthy that several tasks scoring below adequate in Round 1 or 2 still ranked highly in Round 3. This phenomenon was most common for domains with fewer nominated tasks and may reflect a lack of viable options. Alternatively, this may also indicate a willingness to use less than ideal tasks, either out of necessity as just mentioned, or because of easy availability and increased familiarity. The RMET is a good example of this. It is among the most widely used and translated social cognitive tasks32 and received the overall highest rating of suitability for cross-cultural use. However, translation does not guarantee cultural appropriateness, and recent years have seen a sharp increase in concern regarding its validity11 and growing evidence of cultural bias33,34,35. As such, we encourage critical evaluation of existing measures and thoughtful consideration of measurement when designing studies.

We also encourage continued development of novel tasks that are proactively designed to be used cross-culturally. Sensitive cultural adaptation of any cognitive measure is difficult and requires due process, in which researchers need to pay close attention to concept equivalence across cultures. For example, results from previous studies on functional capacity and interview-based measures of cognitive impairment showed that these adaptations usually require substantial edits and that the content of the tasks needed to be adapted36. Thus, applying these same principles to social cognitive tasks, that often use complex and nuanced social stimuli, is an even greater challenge but one that should not be neglected (see refs. 37,38 for suggested guidelines). It also bears noting that work of this type is resource intensive, and that limited funding has previously been cited as a primary barrier31. We therefore encourage investment on the part of funding agencies and foundations.

In addition to the general challenge of developing and validating culturally sensitive tasks, another important element will be to ensure measurement invariance across adaptations. Most social cognitive measure validation studies analyze only basic psychometric properties, such as internal consistency or concurrent and criterion validity. Relatively few studies have applied advanced statistical modeling to estimate measurement properties (see ref. 39 for an exception). It may therefore be helpful to use archival data to test whether some widely used measures are invariant across cultures and to consider measurement invariance in future validation efforts.

Moving forward, it may also be fruitful to emphasize continued development of paradigms rather than specific tasks. For example, the basic structure of the TASIT or the Hinting task, in which participants must interpret interactions between characters, is quintessential to social cognition and could be retained while the specific stimuli or scoring criteria could be adapted to apply more broadly to multiple cultures. A recently developed multiracial version of the RMET also provides a good example of this idea. Here, Kim and colleagues retained the structure of the RMET but updated the stimuli and answer choices to produce a more inclusive version of the task that may mitigate some of the bias introduced by only using white, European faces. Future work may also benefit by adapting novel paradigms from social and experimental psychology. Social cognitive research in the general population has been moving from static paradigms based on the perception and interpretation of social stimuli to more active, dynamic paradigms40 such as dyadic interactions (e.g., 41) that may allow for the assessment of social cognitive processes, like emotion recognition, in real time and in more naturalistic ways. These paradigms have substantial technical and analytical demands but might bring novel insights about the nature of social cognitive difficulties observed across clinical conditions.

As our study represents a consensus-based effort to identify cross-cultural and transdiagnostic social cognitive assessments, some limitations require consideration. First, our RHG included individuals with varying expertise including early career individuals, industry representatives, and individuals with lived experience. While this significantly increased the diversity of perspectives in the RHG, these forms of expertise were not equally represented within the RHG and not all members were as familiar with the breadth of existing social cognitive assessments, which could have skewed our results toward tasks that are more widely used and therefore more familiar. Services users were also underrepresented in the expert survey and RHG, which prevented us from broadly capturing their viewpoints. Accessibility of social cognitive tasks, particularly for service users, should be prioritized in future consensus-based work. Second, just over 25% of the experts invited to the initial survey responded. These experts represented a wide range of countries, but the majority were from North America and Europe and expertise in schizophrenia was most common. Broader representation may have yielded a different set of tasks for consideration by the RHG. Likewise, our RHG lacked representation from Spanish- and Arabic-speaking countries as well as African countries, which account for significant portions of the global population. Future work should strive for broader representation, and when possible, consider multiple languages, including indigenous languages. Third, the data generated here may be viewed as being primarily schizophrenia-focused. Expertise in schizophrenia was disproportionally represented compared to other specific disorders (e.g., autism); however, over half of the experts who responded to the initial survey (53%) identified as having primary expertise in areas other than schizophrenia. Similarly, of the 22 academic and clinical RHG members, 40% worked in populations other than schizophrenia. Thus, we believe this work is still widely applicable and relevant to fields outside psychosis but acknowledge that the results of the Delphi Process may reflect perspectives more heavily weighted by schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Finally, we focused on assessments that are appropriate for adults. Additional work will be needed to identify the most suitable assessments for children and adolescents.

Conclusion

Harmonization of social cognitive research has been significantly limited by a lack of cross-culturally and transdiagnostically valid assessment tools. Results of the global expert survey and subsequent consensus process reported here underscore the relative dearth of suitable measures but do identify a small selection of assessments that appear to be appropriate for current use. These tasks should be explicitly evaluated in cross-cultural and transdiagnostic studies. Additional efforts should also be made to continue adapting existing measures and to develop novel measures that can be used in each of these capacities. Notwithstanding these issues, the tasks identified here represent multiple social cognitive domains beyond the traditionally considered core processes of mental state attribution and emotion processing. In addition to guiding future research, identification of these tasks may provide a much needed springboard for increasing assessment of social cognition in clinical practice, where it remains under-utilized42.

Methods

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of Texas at Dallas (IRB-23-177).

Expert survey for task nomination

Survey content was drafted by the conveners of the RHG (AP, MH, and TZ) and then further refined and augmented with input from RHG-members. The final survey consisted of two primary parts: (1) Background information; and (2) Task nominations for future use. For part 2, respondents were prompted to nominate social cognition tasks that they believed were suitable for: (a) International and/or cross-cultural studies; and/or (b) Transdiagnostic studies. In a separate question, this section also allowed respondents to nominate tasks that may not currently be suitable for either of the intended uses but that may show promise with continued adaptation and further development (see Supplementary Table 1). A final portion of the survey queried current use of social cognitive assessments and perceived measurement-related barriers within social cognitive research, the results of which will be reported elsewhere. A copy of the survey is available in Supplementary Materials.

In parallel, the definition of “expert” was formulated first by the conveners and then edited via group discussion with the RHG.

The term “expert” for academic researchers was defined as follows:

-

research experience (either academic or industry) in the field of psychology, psychiatry, social neuroscience, or an allied discipline for at least 4 years and currently active in one of those fields, AND at least 2 peer-reviewed publications on social cognition, of which at least 1 is as first, second, or senior author, and of which at least 1 has been published in the last 5 years.

-

for researchers from non-English speaking countries, articles written in languages other than English qualified if they were published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Non-academic expertise (e.g., clinicians, students, industry team members, or service users) was defined as:

-

hands-on experience with, or intricate knowledge of, at least 2 social cognition paradigms.

The online survey was implemented in REDCap43 (hosted at The University of Texas at Dallas) for data collection and management, and subsequently distributed via emailed invitations through the RHG-members’ familiarity with experts, as well as supplementary literature searches by graduate students. All RHG members qualified as experts according to the definitions above and were therefore encouraged to complete the survey as well. The estimated duration time for filling out the survey was 10 min. Data for the expert survey were collected between late October 2022—early January 2023.

In total, 381 experts were invited to participate anonymously via an emailed survey-link and asked to share the link with other potential experts meeting the criteria. Ninety-eight experts residing in 25 countries across five continents responded to the invitation and provided digital consent. 50% of respondents identified as men, and age was normally distributed (range: 20–70+; mode = 40–44 y). Most experts (70%) identified professionally as professor/lecturer (any level), 36% as researcher, 18% as a clinician, and 6% as service user/other. Schizophrenia/psychosis or high-risk for psychosis was checked by 46% of experts as their main study population of interest, followed by general population (13%), and autism, bipolar disorder and neurodegenerative disease (all 7%). For additional detail on respondent characteristics, see Supplementary Table 2.

The Delphi methodology

The Delphi method is a structured communication technique used to achieve consensus among a group of experts by soliciting their opinions through an iterative series of questionnaires and providing them with controlled feedback44. The method is based on the concept of collective wisdom, which assumes that the combined opinion of multiple people is closer to the truth than a single individual’s perspective45. To obtain consensus, group members complete a series of online, anonymous questionnaires from which results are aggregated in a systematic manner and then presented back to the larger group. This process of responding and receiving/incorporating feedback (i.e., a “round”) is repeated until group consensus is reached. New information can be introduced at any point or during any round, and ensuring anonymity is thought to reduce undue influence from any (especially more influential) group members and the pressure to conform. This process has previously been used in psychological assessment research (e.g., 46), including studies focused on cross-cultural assessment47 and one study that sought to identify social cognitive assessments for use in Japanese individuals with schizophrenia48. The Delphi portion of this study consisted of 3 consecutive rounds of online questionnaires, further outlined below.

Delphi expert panel selection

Panels with 10 to 50 members are recommended for Delphi studies49. As such, the original RHG membership, comprised of 13 international members of the Schizophrenia International Research Society, as well as two service users and two industry representatives (note: one of the industry partners was unable to continue their participation due to time constraints leaving only one industry representative in the final RHG.), was expanded to include experts from clinical specializations other than schizophrenia/psychosis based on RHG member recommendations. Clinical fields of expertise included: autism, bipolar disorder, neurodegenerative disorders, pediatrics and acquired brain injury. The final group of 26 experts consisted of residents from: USA (8), the Netherlands (4), United Kingdom (3), Australia (2), Canada (2), South Korea (2), China (1), France (1), Italy (1) Slovakia (1), and India (1). Members of the RHG were diverse in gender, race, ethnicity, and career stage (see Table 4).

Delphi procedure and data analysis

After the expert survey was completed, task nominations were collated and used to build a database containing a description of each task as well as a summary of the currently available psychometric data for that task. To the extent possible, information pertaining to reliability (e.g., test-retest reliability, internal consistency), validity (e.g., convergent and discriminant [including consideration of overlap with cognitive performance assessments], criterion, distribution of scores, sensitivity to group differences), practicality of administration, and tolerability (e.g., pleasantness or unpleasantness of completing the task) was included. This database was distributed to RHG members at each round to aid their evaluations.

For each nominated task the overarching goal was to reach a consensus score and establish its utility for cross-cultural and transdiagnostic research. At the beginning of each round, relevant information (i.e., the database) and/or feedback from the previous round was provided to allow the experts to modify their opinions with the aim of reaching group consensus. All tasks were rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0–4: 0=not possible to rate or insufficient information, 1 = inadequate, 2 = adequate, 3 = good, 4 = excellent. Our operationalization of consensus was an interquartile range (IQR) ≤ 1. For a four- to five-point Likert scale, an IQR of 1 or less is considered a high level of consensus50,51. Ratings were conducted anonymously while unique user IDs of participants were collected to monitor variation in expert responsiveness across all three rounds. As noted above, off-line and new information could be suggested at any point and/or during any round. After each round, the tasks for which consensus was not achieved moved into the subsequent round for re-rating. Data collection for round 1 started in May 2023 and round 3 was finalized in January 2024.

Round 1

Eighty-one different social cognition tasks were nominated in the expert survey and included in Round 1. The objective of the first round was to rate the overall quality of each nominated task based on the three considerations listed below:

-

1.

Does the task really measure social cognition, and does it tap into at least one social cognitive domain?

-

2.

Is the task generally a “good” task given what you know about its psychometric properties?

-

3.

Is this task relatively easy to administer and take or it is too onerous (e.g., burdensome) to be useful?

Individual scores of 0 (“not possible to rate or insufficient information”) were excluded before calculating the mean and IQR for each task. To maintain high responsivity, it was deemed necessary to limit the number of included tasks for subsequent rating rounds. Thus, tasks receiving a consensus average score of less than 2, indicating a rating of less than “adequate” were omitted from further consideration.

Round 2

Eighteen tasks that did not reach consensus in Round 1 were rated once more in a similar manner as for Round 1. These tasks were presented along with information on the average panel rating, each expert’s own previous rating (observable with the unique, anonymous user ID for each participant), and an overview of comments that were offered by experts in support of their ratings in the first round. In addition, 10 newly suggested tasks from round 1 were included to collect an initial rating. As only two old tasks and two newly suggested tasks did not reach a consensus score after Round 2, it was determined ad hoc not to request our RHG members for an additional rating for these tasks.

Round 3

After the consensus procedure, the goal of the third round was to identify the best tasks for cross-cultural and transdiagnostic use. Before this final round, tasks were categorized according to social cognitive domain by the conveners, after independent classification and a consensus meeting. The domains adhered to the four domains distilled from the SCOPE study52: emotion processing, social perception, theory of mind/mental state attribution, and attributional style/bias. A fifth domain was added specifically for empathy tasks, which were not included in the SCOPE study. Tasks assessing multiple domains were included in each applicable domain.

In Round 3, RHG members were then asked to identify and rank their top 5 tasks within each social cognitive domain and provide a rating of the overall suitability of that task for the intended use (1 = poor, 3 = fair, 5 = good, 7 = very good, 9 = superb). This was first requested for cross-cultural use and then for transdiagnostic use. To identify top tasks, mean rank was reverse coded so that higher scores indicated better tasks and then weighted by the number of times a task was selected within its social cognitive domain (e.g., (mean rank × number of times the task was selected)/18 raters). Thus, a task with a mean rank of 3.0 based on 10 rankings would have a weighted rank of 1.67 and would be preferred to a task with mean rank of 5.0 (the highest possible) based on just two rankings, which would have a weighted rank of 0.55.

Responses