Harnessing artificial intelligence to fill global shortfalls in biodiversity knowledge

Introduction

Biodiversity is essential for human well-being, yet is increasingly threatened. Biodiversity is also complex, scale-dependent, hard to measure and full of surprises. Unlike the relatively simple causal link between atmospheric greenhouse gas concentration and climate change, the biodiversity story is more nuanced. The grand challenge in ecology and conservation is to be able to answer the following crucial questions. How many species do we have on Earth? Which populations are declining? Which areas are essential to protect? When will tipping points be reached? How should we best meet the 2030 global biodiversity targets set out in the Kunming–Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF; https://www.cbd.int/gbf)1? Why do contemporary extinctions exceed background rates? Adequate answers to these and other questions are needed to capitalize on the current global momentum toward nature conservation.

Unfortunately, despite large volumes of data being collected, nearly all GBF targets and indicators are missing essential information, which is needed both to establish baselines and to monitor progress. Persistent biases dating from the 1980s have led to conservation efforts being focused repeatedly on the same taxa, which (counterintuitively) are not always those with the greatest levels of risk2. Overall, biodiversity is well described in only a small fraction of the world3 and existing data are biased toward common species and populated areas in the Northern Hemisphere4,5. Little is known for many species beyond their names and where they live. Information on how a particular species functions, how it speciated and how it interacts in communities is often absent, especially for species occurring in the ocean2. These knowledge deficits span taxonomy to species interactions and have been organized into seven defined shortfalls in global biodiversity knowledge6,7 that capture the breadth and complexity of biodiversity in measurable ways. Overcoming these shortfalls is essential for calculating essential biodiversity variables8, meeting all biodiversity-based GBF indicators and addressing the most pressing challenges to biodiversity, which range from obtaining detailed on-the-ground knowledge to understanding national trends.

Ecologists and conservation researchers need to harness the current unprecedented levels of interest and global coordination in biodiversity protection generated by the GBF alongside emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and, more specifically, data-driven machine learning (ML), that can handle diverse and rapidly expanding datasets. An open question is how we can best leverage these technologies. To date, the rapid rise of AI technologies and methods in ecology and evolution has been mostly focused on a small set of conservation topics (reviewed elsewhere9,10,11) and data-collection applications, such as bioacoustics12, camera traps13,14 satellite imagery and remote sensing15. Reviews of AI applications in biodiversity loss16 and AI methods for ecologists17 have already been published. The present Review considers how AI could address critical knowledge gaps in the broader fields of biodiversity science, which span spatial scales, genes, functions, phylogenies and species interactions. We note that owing to the extremely rapid development of AI, many of the publications cited in this Review are currently available only in non-peer-reviewed formats (conference proceedings or preprints).

In this Review, we delineate the current state of the seven biodiversity shortfalls7,18, discuss how they are being addressed with AI and identify where AI offers the greatest potential for bridging the remaining gaps (Fig. 1). Where AI methods have not yet been used to address all seven biodiversity shortfalls, we recommend avenues of investigation that map the needs of each shortfall to specific AI solutions and place each solution in the context of the required steps, from data imputation and analysis to conservation decisions. Finally, we provide a critical analysis of the realistic limitations of AI technologies; although the proliferation of foundation models (including molecular19, cellular20,21 and organismal22 models) coupled with generative AI holds promise for reducing all biodiversity shortfalls, AI is not the answer to every challenge.

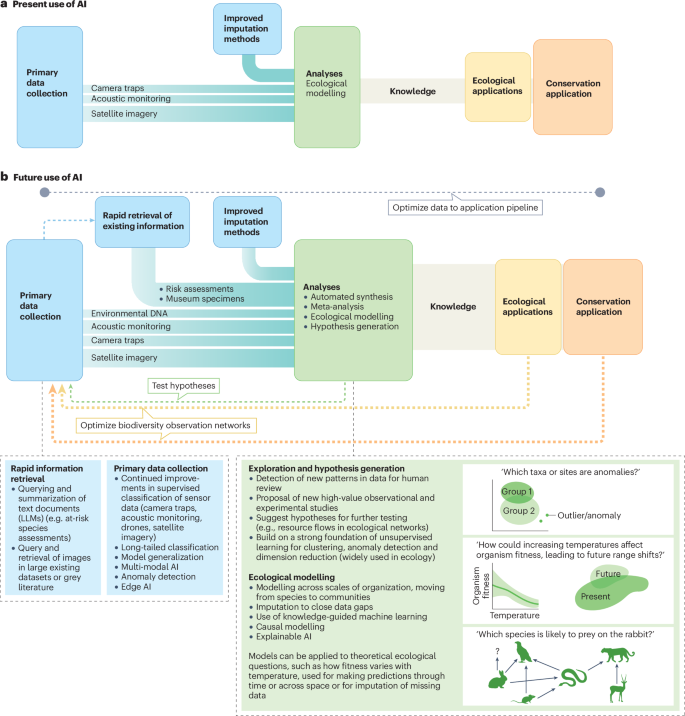

a, Artificial intelligence (AI) is widely implemented in the data–decision pipeline for conservation applications (those relating to species of conservation concern) but is less often integrated into the broader subfields of ecology. In consequence, most biodiversity shortfalls remain relatively unexplored. The increasing emphasis on satellite imagery and imputation methods, which generate large datasets and involve statistical modelling, is likely to drive further uses of AI. b, The future development of AI could help to fill knowledge gaps in several areas. These improvements generally apply across multiple biodiversity shortfalls, although some tasks benefit more than others from specific improvements. The size of the boxes and the width of the connecting lines represent the relative importance of the contributions of AI to the data-generation and conservation-application processes. LLM, large language model.

Taxonomic descriptions

The Linnaean shortfall refers to the gap between the number of species on Earth and the number that have been formally described7. This shortfall is arguably the most foundational, as nearly every field in ecology, evolution and conservation relies on naming and cataloguing species to assess biodiversity. Nothing can be done to understand a species that is not known to exist.

Challenges

The size of the Linnaean shortfall is unknown, because estimating the size of this gap relies on counting the number of species that have been described and estimating the number of non-described species, both of which involve uncertainty. Approximately 2 million extant species have been described23 of the estimated 8.7 million eukaryotic species thought to exist on Earth24, although estimates vary widely25. In general, the size of the Linnaean shortfall is thought to increase as the size of an organism and its complexity decreases26 and to vary geographically along with a variety of other traits7,27,28 (see the Wallacean shortfall). Despite the fundamental nature of the Linnaean shortfall and the currently heightened global risk of species extinction, the number of newly named species has not increased since the 2000s2. Indeed, taxonomy is a severely underfunded scientific discipline that is itself threatened with extinction29.

Past and future role of AI

AI has so far been used to mitigate the Linnaean shortfall in two major ways: to impute the estimated total number of taxa30 and to identify new taxa in existing datasets (Fig. 1). Automated identification of previously undescribed taxa is a very promising task for AI that might be accomplished through identification of new taxa in existing images22, DNA samples31 or acoustic recordings and leveraging of modalities (such as DNA or acoustic analysis) that can indicate the presence of taxa as yet unseen32.

Novel taxa have been identified in raw sensor data, including via DNA barcodes31,33 and citizen science images22,34. The image-classification models BioCLIP22 and BIOSCAN-CLIP31 are not designed to pinpoint new species, but can be used to label putative examples of new species by association with known template images or DNA sequences, respectively. WildCLIP focuses on the retrieval of images displaying certain attributes of an animal or its environment, which could be used to interrogate diverse datasets35. Although such approaches are currently in the early stages of implementation, they offer considerable potential for incorporating techniques from the ML subareas of open world classification and category discovery32, which involve the identification of new categories (such as species) in unlabelled datasets (such as image libraries) that could contain both previously known and as-yet-undescribed categories.

Looking ahead, AI tools might contribute to tasks designed specifically to enable species discovery. For example, once a new species is identified (either manually or via AI-assisted discovery methods32), AI vision–language models might be able to assist taxonomists in crafting a species description by picking out and describing its distinguishing features34,36,37. Such methods could draw upon interpretable AI techniques integrated with species-detection algorithms such as those used in BioCLIP or BIOSCAN-CLIP. Other algorithms might be used to recommend where, when and how to search for novel species: for example, approaches inspired by active learning could identify areas where there is high uncertainty in the diversity of certain taxa. This process results in an active learning feedback loop (Fig. 1), in which hypotheses proposed by both humans and algorithms are validated and the results are used to train further algorithms with improved performance. Such active learning processes are predicted to be instrumental in the design of future global monitoring networks38. Contributions from AI might, therefore, not only increase the rate of species discovery and description but also the effectiveness of current and future generations of taxonomists.

Estimates and patterns of abundance

The Prestonian shortfall refers to the lack of knowledge of the abundance of a species and its trends in both space and time. Aside from the fundamental importance of accurate estimates of species abundance to population biology and evolution, knowledge of abundance is also critical to defining a species’ conservation status and predicting its risk of extinction. However, addressing the Prestonian shortfall represents a considerable challenge because it involves counting (or estimating) the number of all individuals of a species present at a given point in space and time.

Challenges

From a data perspective, measuring the true abundance of a given population requires an exhaustive census of every individual of the relevant species present within a defined spatial and temporal window. This laborious exercise is very rarely completed even for relatively charismatic, easily detected and well studied taxa such as birds39 or large mammals. As a notable exception, the Center for Tropical Forest Science (CTFS) Forest Global Earth Observatory (GEO) has established forest plots specifically for measuring the true abundance of tropical tree species40. However, even for stationary and relatively well described tree species, conducting such censuses requires an enormous amount of effort.

A practical alternative to a complete census is to estimate both species abundance and its spatiotemporal trends from a statistically representative sample of individuals drawn from the entire population. The essential challenge of this approach is to accurately estimate the number of individuals that are present in the population but not sampled, which requires repeated sampling in either space or time. Two broad categories of population estimation model exist: marked, in which specific individuals are tagged or can otherwise be identified when re-sighted in repeated surveys; and unmarked, in which individuals are counted but cannot be identified as a specific (re-sighted) individual. The relative abundances of multiple species or trends in relative abundance among species might be sufficient for some applications and can often be inferred from count data alone18,39.

Notably, although the explosion in citizen science data and the availability of digitized museum specimens have made important contributions to documenting the presence of species across their ranges (as discussed in the section on the Wallacean shortfall), these unmarked data sources usually do not measure abundance directly and might be too sparse in space and time to support robust estimates of abundance.

Past and future role of AI

To date, AI-based analysis of sensor data (such as camera trap images and acoustic recordings) has been applied to mitigating the Prestonian shortfall by generating unmarked data for statistical abundance estimation41,42. For example, occupancy estimates derived from repeated sampling43 and time-to-detection models44 that are based on the automated classification of bird song produce species abundance estimates similar to those derived from traditional human surveys45. Automated classification can also be combined with grids of sensors, such as acoustic recorders, to produce high-resolution maps of sound sources that can be used to estimate the abundance of sound-producing species46,47.

AI is already reducing the Prestonian shortfall for many species by increasing the efficiency of human experts in identifying specific individuals in collected images, which facilitates the non-invasive marked estimation of species abundance48. This work started with the publication in 1990 of the first methods of re-identification based on computer vision49. Early attempts involved the use of statistical pattern recognition derived from low-level features and geometry14,50,51. Advances in person re-identification using deep learning52 have now been applied to images of animals of various species53,54,55 and have led to notable improvements in re-identification, particularly when high-quality, well focused images of single individuals taken by human experts were assessed.

AI methods that can identify individual organisms, not just their species identity, are poised to contribute even further to mitigating the Prestonian shortfall by enabling data obtained from passive sensors to be used in marked abundance models. However, much work remains to be done to increase the resilience of computer-vision-based re-identification to poor-quality images, for example those captured without a human photographer (such as in camera-trap data14,56). In addition, these methods could be expanded to include many more data modalities, such as video57,58,59, drone or unmanned aerial vehicle recordings60 and audio files61,62. AI applications for wildlife population monitoring (such as Wildbook; https://www.wildme.org/wildbook.html) would also benefit from progress on the ‘open-set challenge’, which involves not only identifying confidently that an individual has never before been seen63 but also recognizing and matching sightings of new individuals over time64. We anticipate that progress will also be made on the incorporation of experts into participatory and iterative human–AI systems to reduce the amount of expert input needed to derive abundance estimates65 and to improve resistance to category errors, such as assigning images of multiple individuals to a single identification or splitting images of a single individual into multiple identifications.

In the long term, considerable development work is needed to enable computer vision systems to efficiently recognize individuals without clear biometric markings and to recognize the same individual as their markings change over time. Such improvements might involve the recognition of specific individuals from their behaviour, gait or vocalizations, or the integration of additional modalities, such as hyperspectral imaging or environmental DNA (eDNA) analyses. Additional biological attributes and contextual information derived from mechanistic studies of species behaviours, such as social interactions, demographic status and territories, could also be integrated into re-identification systems. Additionally, interdisciplinary research on statistical estimates of abundance is needed, for example, to develop estimation methods that take into account the continuous-value confidence scores of AI models47 or make use of mixed-granularity species identification data, in which some sightings can be identified at the individual level, whereas others can only be confidently identified for a small subset of the population.

In contrast to the several decades of experience in the application of AI-based analytic methods to image databases, the application of these methods to acoustic61 and other data types collected in the field remains limited and emerging. Progress in computer vision could lead to the development of improved methods for the aerial census of large groups, which could build upon existing methods used to accurately count the number of individuals in crowds66,67. The growing availability of eDNA data, particularly those obtained using field-deployable sequencing technologies, offers another potential avenue for species abundance estimation. However, the conversion of eDNA concentrations into reliable abundance estimates remains challenging, owing to the presence of complex environmental factors that affect DNA persistence and detection68. AI approaches could make estimates derived from eDNA concentrations more robust by accounting for these environmental factors and by integrating eDNA data collected using other sensor types. Finally, we note that the AI-supported species abundance estimation methods described in this section have generally provided single snapshots in time. Additional progress towards the use of AI for forecasting time series and understanding drivers of population change, including through process-based and knowledge-guided ML models of population dynamics69,70, is expected to contribute further towards reducing this shortfall.

Biogeographic species distribution

The Wallacean shortfall refers to the lack of detailed information on the biogeographic distribution of species. The documentation of species distributions dates from the early 1800s and, as such, is one of the oldest endeavours in biodiversity science. Moreover, the Wallacean shortfall affects nearly every subfield of ecology, including understanding the effects of climate change on biodiversity and the reconstruction of historical speciation events. Accurate data on species biogeographic distributions is essential for conservation because range size is one of the best predictors of extinction risk71,72,73 and is one of the main criteria for assignment of at-risk status74. Knowledge of biogeographic species distributions is also essential for mapping species, biodiversity hotspots and ecosystem services. This information directly feeds several important biodiversity indicators, such as the Species Protection Index75.

Challenges

Addressing the Wallacean shortfall is relatively simple in principle, in that it can be filled by simple occurrence data, which are increasingly drawn from crowdsourced initiatives such as iNaturalist76. However, although the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF; https://www.gbif.org/) now contains over 3 billion records, these data are biased toward terrestrial areas2, certain taxa (especially popular birds), the Northern Hemisphere and locations within 1.0 km of roads77. Expert species-range maps derived from taxa-specific sources (including conservation guides and at-risk assessments) also provide distribution information for many taxa, but these often lack the granularity needed for use in conservation applications, such as the estimation of species–habitat relationships.

Past and future role of AI

One of the most promising ways in which AI can be used to fill the Wallacean shortfall is in the processing of incoming primary data collected from sensor arrays (Fig. 1). Technologies such as high-resolution satellite and aerial remote sensing in a wide range of spectra, stationary image capture, acoustic sensing and eDNA analysis are increasingly being used to provide species data for sparsely covered and/or inaccessible locations. These innovations are already resulting in surprising discoveries, such as new colonies of emperor penguins78 and advances such as the ability to monitor whales in remote locations79. Species occurrences can also be extracted from non-target acoustic recordings, images on crowd science platforms (such as iNaturalist) and social media posts80.

A second major and well integrated effort to fill the Wallacean shortfall has involved the use of species distribution models (SDMs) to impute missing data. SDMs used to predict a species’ spatial distribution from environmental or habitat data have rapidly adopted ML techniques such as boosted regression trees81. Modern SDMs are now beginning to incorporate more-powerful ML techniques that can handle complex interactions with multiple data types, such as remotely sensed land-cover classes and continuous local climate measurements82. AI-based statistical model integration is an even more powerful tool83 for the analysis of multimodal datasets that can handle multiple types of species occurrence data — for example, presence-only community science, presence–absence plot data and remote sensing imagery (Box 1). The development of standardized protocols and competitions such as GeoLifeCLEF (one of several challenges in ImageCLEF (https://www.imageclef.org/), the Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum (CLEF) cross language image retrival track)84 are extending the success of AI-assisted SDMs to other macroecological models used to predict biodiversity metrics, such as species richness85.

However, many challenges remain to be addressed to enable meaningful gains to be made in primary data collection and data synthesis. AI-assisted methods offer the potential to decrease known data gaps by targeting severely under-sampled areas (such as the deep ocean) and taxa (such as fungi) via active learning methods that optimize future data acquisition from in situ sensor networks and community scientists86,87. Extreme edge computational approaches increasingly move AI to the sensors themselves, in the form of smart camera traps and acoustic arrays that enable automated and adaptive data collection. Advanced techniques are also needed for spatial bias correction38,88, to improve models of undersampled species that are based on well sampled species89,90, and to model community assemblages and turnover91. The development of these methods requires cross-disciplinary collaborations of ecological statisticians and AI researchers92. Although multimodal datasets (for example, those that integrate camera trap and community science data) are already proving useful83, future work could address the computational challenges associated with the analysis of large remote-sensing datasets by making use of models that efficiently encode spatially varying data representations, which are useful for many downstream tasks93,94. Finally, where possible, the utility of AI methods for estimating spatial distributions of species should be rigorously quantified using best-in-class, expert-verified evaluation datasets. The creation of such ‘gold standard’ datasets is challenging but deserves attention from the biodiversity community95,96.

Abiotic tolerance and fundamental niche

The Hutchinsonian shortfall refers to a gap in understanding of the tolerance of a species to abiotic conditions, including temperature, precipitation, soil, water and terrain. This suite of abiotic tolerances is often referred to as the Grinnellian fundamental niche, which is considered to be the multidimensional environmental space in which a species can persist97,98. Knowledge of abiotic tolerances is particularly important in the context of climate change because rapidly changing abiotic conditions are driving mismatches between species occurrences and tolerances that pose a threat to conservation efforts. Mitigation of the Hutchinsonian shortfall could improve predictions of population trajectories and range shifts under climate change99.

Challenges

Information on species tolerances comes from two primary sources: physiological data derived from study of the organism and occurrence data from field observations. Physiological data collected about organisms in field or laboratory experimental settings can be used to generate models that generate performance curves for a given organism under different abiotic conditions. These data are challenging to obtain and exist only for a subset of species100. Additionally, such studies often fail to account for environmental factors that affect performance under field conditions and rarely capture intraspecific variations (see Raunkiaeran shortfall) or consider phenotypic plasticity101. Alternatively, occurrence data from field observations of an organism can be linked to data on prevalent abiotic conditions to characterize a species’ realized niche.

The differentiation of fundamental niches (the potential for toleration of extant conditions) from realized niches (environments where an organism is actually found) remains a challenge, given that biotic factors and dispersal capabilities also shape species distributions102. A further challenge is the lack of data on the abiotic environment, particularly at the fine spatial scales needed to precisely quantify the abiotic tolerances of organisms.

Past and future role of AI

AI is an obvious candidate for inferring an organism’s tolerances from field observations and occurrence data. Increasingly finer-resolution imagery from satellites (Box 1) and drones, thermal imaging data and precise light detection and ranging (LiDAR)-generated three-dimensional (3D) models of surface features can be the base ingredients for extracting a highly refined picture of species habitats or proxies that can be used to estimate such habitats. Although such raw data do not directly inform scientists about habitats, they can be used to extract the required information about phenology, soils and climate. Some sensors track organisms directly. Animal tracking, although particularly relevant to the Hutchinsonian shortfall, is also relevant to the Wallacean and other shortfalls.

Looking forward, alongside the advances in satellite-derived imagery used to identify habitat associations (Box 1), ground-to-space systems such as International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space (ICARUS) could greatly enhance our understanding of abiotic tolerances and detailed behavioural responses to abiotic conditions (reviewed elsewhere103). For plants, abiotic conditions could potentially be harvested from photographs (also discussed in relation to the Raunkiaeran shortfall). However, laboratory-based experimental work is needed to complement such observational data. AI could be helpful in building 3D models of wingbeats for birds using structured light and high-speed cameras104, other detailed animal tracking movements105,106 or scent-based molecule detection107 (which could be used to detect stress hormones in laboratory animals, for example). Looking to the future, the creation of accurate ‘digital twin’ ecological system models108,109,110 will require abiotic tolerance data derived from these AI methods as well as process-based AI approaches that combine abiotic tolerance information with additional observations to track and predict biodiversity change.

Functional trait variation

The Raunkiaeran shortfall highlights the lack of knowledge of both intraspecific and interspecific trait variations, the ecological functions arising from species traits, how these functions are influenced by interactions with other traits, and which traits act in tandem to provide specific ecosystem functions.

Challenges

Obtaining the true distributions of trait values within a given population requires a comprehensive assessment of every individual’s traits to be conducted within a specified time frame, which is logistically impossible. For that reason, researchers have largely focused on compiling species mean values derived from measurements of museum specimens or individuals in the field as well as extraction of trait data from guidebooks and the scientific literature. These efforts led to the development of large, publicly available trait databases111,112,113,114,115. Efforts over the past 15 years have focused on intraspecific trait variability112,116 and the potential for some traits (such as diet and foraging characteristics) to show substantial spatiotemporal variation even within an individual117. However, considerable taxonomic gaps remain; most trait databases focus on plants116 or tetrapods111,112,113,115 and only a handful include invertebrates114,118, fungi and microorganisms118,119, for which comprehensive taxonomic coverage is often lacking. Geographic coverage is also uneven; regions in the Global South and ecosystems such as tropical forests and deep oceans typically lack comprehensive trait data. Finally, our knowledge of traits often centres on easily measurable morphological characteristics, which are only sometimes clearly linked to ecological functions120,121. These factors limit our understanding of trait–environment relationships. Comprehensive data are urgently needed on behavioural, physiological and life-history traits, which are crucial for understanding species’ ecological roles and interactions.

Past and future role of AI

Current AI techniques to address the Raunkiaeran shortfall typically focus on extracting trait information from digitized museum specimens122 and images provided by citizen scientists through the burgeoning field of imageomics123. Most efforts have concentrated on easily measurable (often morphological) traits, but more-complex applications of AI are emerging. For example, in a study of birdwing butterflies, an AI model identified subtle differences in wing shape and colour — traits that are challenging for humans to discern124. Likewise, AI has detected colour differences between genotypes of the polymorphic wood tiger moth (Arctia plantaginis) that are typically invisible to the human eye and has analysed pattern signatures of the mimetic eggs of the common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus)125. ML techniques have also been used to impute missing trait data126 and to infer trait combinations that are responsible for species interactions. Computer vision algorithms that learn from image attributes127 could make important strides in addressing the Raunkiaeran shortfall (Box 1).

Several advances could be useful for quantifying ecosystem function. For example, the use of remotely sensed images to assess plant productivity could identify ecological interactions (as described for the Eltonian shortfall). The large strides made in using imagery to identify species and trait composition128 are expected to facilitate the detailed measurement of ecosystem processes such as nutrient cycling, decomposition and food-web energy dynamics.

Looking ahead, AI is likely to continue to make surprising discoveries related to traits that are undetectable by human senses and to further develop this knowledge by adding further data modalities and identifying connections among them. AI could be used to analyse high-resolution 3D scans of collected natural history specimens, such as skulls, pollen129 or fossil plants. Likewise, efforts are also advancing from 2D to 3D, static to video and visible-only to hyperspectral and other imaging techniques, which (for example) could capture the behaviour of flying insects around artificial light sources130. AI could also play an important part in discovering and connecting traits to function within a single context in which multiple species exist.

Evolutionary relationships

The Darwinian shortfall highlights gaps in our understanding of the tree of life and the evolution of lineages, species and traits7. A related but distinct gap is the shortfall in understanding of evolutionary relationships at the population level, which we refer to here as the genetic diversity shortfall (described in Box 2).

The evolutionary history of species is particularly relevant to the study of the evolution of species traits (see the Raunkiaeran shortfall) and species niches (see the Hutchinsonian shortfall). However, beyond its fundamental importance to evolutionary biology, knowledge of evolutionary relationships is also crucial for conservation policy and planning, given that programmes such as EDGE (Evolutionarily Distinct, Globally Endangered) prioritize the conservation of evolutionarily distinct species131.

Challenges

The tree of life has been extensively revised with the advent of molecular biology, initially through the comparison of DNA fragments and now through whole-genome sequencing. Despite considerable advances in these methodologies, the use of molecular techniques for building comprehensive phylogenies remains constrained by data availability7,132. As a result, only a few well known groups, such as birds, some plants and mammals, have comprehensive species-level phylogenies103,133 and many other clades (particularly highly diverse groups such as microorganisms, insects and fungi) lack comprehensive phylogenetic information. Limited data availability also hampers the estimation of time-calibrated phylogenies, which are crucial for the derivation of accurate evolutionary timelines. This process typically involves using the fossil record to set node age constraints, employing molecular clocks to estimate evolution rates and divergence times and using integrated models of fossil and phylogenetic data to concurrently estimate divergence times and diversification rates.

Past and future role of AI

All modern phylogenetic inference methods use computational (albeit mostly non-ML) algorithms134. However, several advances in AI have shown promise for improving the understanding of evolutionary relationships. For example, frequently used ML algorithms such as random forests (which combine the output of multiple decision trees to reach a single result) have been used to improve the accuracy and efficiency of phylogenetic inference135 and graph neural networks represent a potentially fruitful next step in this area. Moreover, guided by phylogeny and the increasing number of sequenced species, AI is starting to be used to extract trait information directly from images136,137,138 in studies of phenotype–genotype correlations139 (see the Raunkiaeran shortfall). AI-harvested information can also be used to study trait evolution. For instance, Phylo-NN140 integrates images with phylogenetic data in a hierarchical manner to generate imageomes (sequences of quantized feature vectors that capture evolutionary signals at varying ancestry levels). Other examples include phylogenetic Gaussian processes for reconstructing ancestral traits141, which provide detailed insights into evolutionary history and trait evolution across species.

Looking ahead, AI has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of evolutionary relationships. Advanced AI algorithms could accelerate phylogenetic reconstruction by leveraging parallel hardware and computational approximations that borrow core ideas from AI to address the combinatorial nature of phylogeny estimation. The power of modern AI methods to synthesize scientific knowledge, coupled with the increasing availability of sequenced genomes, could lead to the development of evolutionary foundation models similar to those emerging at the DNA sequence31,142, cell21, organism and species22 levels. Future applications of AI might also enable trait dendrograms to be inferred directly from images of organisms, potentially including 3D fossil images, to generate testable hypotheses about their evolutionary relationships. AI could also be used to analyse high-resolution 3D scans of collected natural history specimens143 to study trait evolution and reconstruct ancestral states. In acknowledgement of the receptiveness of the AI and/or ML communities to competitions and benchmarks, development of AI methods might be spurred by efforts to extend existing computational phylogenetic benchmarks to multimodal data for phylogeny inference. We note that such benchmarks must be carefully designed to ensure they are as representative as possible of the real-world challenge they pose. Other large-scale datasets such as Arboretum144, TreeOfLife-10M22 and BIOSCAN-5M145 already target the Linnaean shortfall by providing extensive multimodal biodiversity data. Similar phylogeny-focused datasets could challenge the AI community to address the Darwinian shortfall.

Species interactions

The Eltonian shortfall describes the gap in our knowledge of interspecies interactions (including competition, predation, herbivory, mutualism and parasitism) that are fundamental in shaping the ecological distribution and abundance of species. If such biotic interactions are not accounted for, predictions of (for example) population viability and species responses to disturbance are likely to be incorrect. An understanding of species interaction networks also enriches the understanding of ecosystem functioning and resilience to disturbance.

Challenges

The complexity of ecosystems and food webs makes it challenging to identify the presence and strength of pairwise interactions. Although some interactions (such as pollination and predation) involve direct contact between species, such events are often rare and difficult to observe. Other interactions remain invisible, such as competition for scarce resources. Species interactions are often not apparent until after the loss or removal of an individual species causes disruption that reverberates throughout ecosystems. Diet analysis of faecal or gut content — and, increasingly, DNA metabarcoding — has informed our understanding of the richness of trophic interactions (those that control energy flow through food webs via direct consumption of one species by another), although such methods remain costly and have low accuracy for some taxa146. In relation to species interactions at biogeographic scales, field data on species co-occurrence can inform joint SDMs89,147,148, although such correlative approaches can rarely tease apart the mechanistic interactions that underlie co-occurrence patterns149.

Past and future role of AI

The Eltonian shortfall represents one of the most critical data gaps and many exciting opportunities exist for the use of AI to mitigate this shortfall (Fig. 1). AI supports two broad ways to address the Eltonian shortfall: intelligent sensing in primary data collection and data imputation by interaction prediction.

AI is already being used for direct sensing of plant–pollinator150 and plant–pest interactions151 in collections of visual152,153 and acoustic154 data. These initiatives are partly motivated by smart agriculture (that is, the use of advanced technologies to improve agricultural productivity and sustainability). Exciting possibilities exist for using the soundtracks from recorded videos and images of non-focal species recorded in databases (such as iNaturalist) and social media posts to harvest species interactions from existing data. Similarly, large language models (LLMs) could generate summaries of existing detailed text descriptions from guidebooks, grey literature (produced at all levels of government, academia, business and industry outside commercial publishing channels) and conservation assessments. Predictive approaches are of great importance in data imputation because sampling of species interactions is much harder than sampling of species occurrence, even when supported by AI. Predictive tools could help to alleviate this data gap by providing both the basis for probabilistic analyses and effective guidance for additional observation efforts.

AI is now beginning to be used to adapt traditional models of species interactions based on plant–pollinator155,156,157, predator–prey158,159 and host–parasite160 networks by incorporating trait matching, eDNA161, species co-occurrence or even just network structures. Interactions can be predicted even in the absence of traits by extrapolating from partly known interaction networks162 or relying solely on co-occurrence163 using graph dimensionality reduction techniques to generate a small latent interaction space that captures the essential features of the meta-web and even allows some transferability across taxa164. Although these AI-assisted approaches remain limited by the need for more finely grained data sources (such as GPS tracking)165, they are key to the alleviation of data sparsity. Some studies have demonstrated advantages of ML approaches (specifically deep neural networks and random forests) over classic statistical techniques156 but much work remains to be done, particularly in addressing the mismatch between predictions of individual interactions and community properties166 and in developing process-based ML models that realistically constrain network predictions163.

In the long term, one of the obvious uses of AI will be to improve the analysis of ecological and other interaction networks, although such approaches are yet to be widely adopted. Graph neural networks167, a form of deep neural network that performs inference on network structures rather than tensors, seem to be particularly promising. Graph neural networks represent a natural way to learn (multilayer) representations from graphs and to deal with a number of network-related problems168 but have had slow uptake in ecology. Graph tokenization169, a process similar to text tokenization, offers an alternative to graph-based learning with conventional deep neural networks. Ultimately, although graphs are likely to be a natural match for AI-assisted analysis of interaction and species networks, the extent of the improvement gained for ecological networks remains to be seen170.

AI-assisted analysis of interaction and species networks has many potential applications, such as anticipation of extinction cascades. Once a metaweb has been characterized, algorithms can predict which extinctions and co-extinctions would have disproportionate effects on network structure171 (and, probably, on network function). Combined with Bayesian reasoning, this approach has delivered automated decision-making support that promises substantially improved conservation outcomes172 and could improve analyses of the effects of threats on food webs173. For example, the use of AI has led to considerable progress in understanding the patterns of historical mass extinctions by first inferring historical food webs from ecomorphological and phylogenetic traits and then evaluating their resilience174.

Summary and future directions

The potential contributions of AI to filling the seven global biodiversity shortfalls extend far beyond those completed so far (Table 1). We believe that AI is poised to have a major effect on the seven shortfalls in three broad areas: continued improvements in data collection and processing; new approaches to ecological inference and prediction; and collaborative research design and hypothesis generation (Fig. 2). The first two areas have already received attention in ecology and further advances and applications are clearly on the way. The third area remains in its infancy.

a, Important challenges relating to each shortfall are presented along with summaries of the associated scientific fields and examples of conservation applications, including proposed or accepted indicators for the Kunming–Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF): the Red List Index (RLI), the Living Planet Index, the Red List of Ecosystems, Evolutionarily Distinct, Globally Endangered Species (EDGE) and targets such as Target 3 of the GBF (protection of 30% of the land and sea by 2030, also known as 30 × 30). b, Connections between these shortfalls and applications of AI might provide the greatest potential for future advances beyond those already underway. The heights of the right-hand boxes indicate the relative potential for such gains.

The best established and most widespread applications of AI in filling biodiversity shortfalls relate to increasing the speed, scale and effectiveness of data collection and processing. To date, much of this work has centred on the use of automated sensors and ML methods, primarily from computer vision, to generate new records of species presence (that is, occurrence or abundance). These data are already helping to fill the Wallacean, Prestonian and Hutchinsonian shortfalls (Figs. 1 and 2; Box 1), mainly through their use in statistical models that relate species presence to abiotic conditions. Particularly promising are extensions of open-world classification and category discovery that could soon reinvigorate the naming of new species (that is, the Linnaean shortfall) via the automated discovery of taxonomic diversity. Below the species level, AI extensions to fine-scale features of organisms will help to fill the Raunkerian shortfall and the genetic diversity shortfall (Box 2). Finally, the generation of large-scale species co-occurrence data or even automated detection of direct species interactions, such as predation events or aggressive vocalizations, could further help to fill the Eltonian shortfall.

In the long term, the speed, scale and effectiveness of data processing must continue to improve as biodiversity datasets expand. A specific area for future growth is the application of emerging techniques for the detection and identification of rare events and anomalies. Addressing the challenges presented by hard-to-detect species, events and other kinds of unusual signal will help to fill all seven shortfalls. Another key role for AI that has largely gone unrealized in ecology is the ability of models to not only automate the detection, classification and analysis of data features that are already known to humans but also to discover novel features and patterns that had not previously been described or even imagined. Examples include traits that are not detectable by human senses, subtle features that distinguish individual organisms within a species from each other, and general patterns in community structure.

The assimilation capacity of AI also has untapped potential to gather and synthesize what we already know175,176. Large amounts of (often publicly funded) high-quality ecological data are present in at-risk species assessments, consultant findings and government reports176, many of which are available online and include more-detailed ecological information than is found in existing compiled datasets. Data-gathering and synthesis activities that could take many person-years could be done much more efficiently by using LLMs177 for the initial stages. AI-assisted data gathering could be especially helpful for meta-analyses, in which data and findings from hundreds or thousands of papers need to be compiled to answer key unresolved ecological and evolutionary questions178. Despite its speed and promise, AI-assisted data synthesis still requires careful checks at all stages of data compilation, analysis and interpretation (Box 3).

Progress has also been made towards using AI-based deep learning to perform inference and prediction tasks that have traditionally been the remit of statistical methods such as regression. These tasks are ubiquitous across ecology and are a natural fit for AI. As the use of AI-based methods continues to grow, improved models are expected to support more-accurate SDMs to assist with the Wallacean shortfall as well as forecasting of time series (which has particular relevance to the Prestonian shortfall), phylogenetic reconstructions and food webs. Particularly important advances could come from the growing use of knowledge-guided ML, explainable AI179 and causal inference180,181, which could go beyond simply describing biodiversity patterns to uncovering their underlying ecological mechanisms. Such approaches have begun to make important contributions in related disciplines182,183 but have not yet been widely applied to addressing biodiversity shortfalls. Other improvements in bioinformatics tools and methods are expected to help to fill the genetic diversity (Box 2) and Darwinian shortfalls. Across all shortfalls, targeting of geographically and taxonomically under-represented biodiversity should be a priority76.

A specific and critical need in ecological inference is to understand connections and interactions across biological scales, especially at the community level. In general, AI is well-suited to the analysis of high-dimensionality data and systems and could be potentially more effective than existing methods at uncovering patterns and processes, both static and dynamic, in large interacting biological systems. The ability to use large, multimodal datasets and collections of models, together with nascent AI methods for data integration and synthesis, to extend knowledge from the species level to the community level will be essential for filling the Eltonian shortfall as well as other shortfalls that are driven by multi-species interactions. This process has begun with the creation of ML versions of joint SDMs184, but moving from species to communities is expected to more accurately reflect ecological dynamics and provide more-direct links to ecosystem functions and services.

Finally, we propose that future generations of AI might fundamentally change the role of computers and computation in ecology and biodiversity research. At present, the contributions of AI remain restricted (like those of ecological models) to a largely top-down framework, in which a tool or model is used to conduct an analysis specified by a human scientist. The value and/or utility of AI in a particular context is determined by how well different tools or models accomplish these predetermined tasks. This framework contrasts with collaborative research partnerships, in which participants iteratively discuss, challenge and build on each other’s ideas to reach insights that could not have been reached by the individual participants alone. To date, such collaborations necessitate interactions between human colleagues.

We speculate that several potential avenues exist through which AI might begin to join human scientists as a collaborative research partner. For example, we see potential for the growth of AI-assisted methods that iteratively and adaptively optimize experimental sampling schemes, in concert with changing input from human researchers, which will feed into coordinated monitoring efforts such as those of Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network (GEO BON)38. The use of AI in non-ecology fields, such as computer-aided drug discovery185 and materials science186, has shown the potential for such models to propose candidate research directions for experimental follow-up. Parallel tasks within biodiversity science could include AI-generated proposals of the existence of undetected species, resource flows, interactions, historical events, or intervention strategies that could be verified with additional research effort. Perhaps the broadest indications of such potential currently lie in LLM chatbots, which can be used by researchers to help them to think through research ideas and directions.

These potential applications of AI are largely in their infancy and breakthroughs are likely to come from the broad integration of ML with expert knowledge and models derived from first principles187,188. The exploration of process-based or knowledge-guided ML models189 that combine new information with existing scientific knowledge will be particularly important to derive ecological knowledge from newly obtained data. For example, AI systems trained on the extensive past climate record and based on transformer architecture190 or graph neural networks191 have already contributed to climate modelling. Knowledge-guided ML69,70 offers a very promising future approach to this problem, in which the results of the AI model are constrained by boundary conditions dictated by physical knowledge of the climate system188,192 or phenological parameters188,192.

Realization of these additional benefits of AI requires communication between biodiversity scientists and AI practitioners. A first useful step in this direction would be a concerted effort to translate biodiversity needs into tractable problems that attract attention from the AI community. Each biodiversity shortfall requires the identification of ecological use-cases along with evaluation data and benchmarks similar to GeoCLEF and BirdCLEF (tracks within CLEF that test and evaluate cross-language information retrieval of topics with a geographic specification and the ability to automate the identification of bird species from song, respectively), which are not usually prepared by ecologists. Development of such use-cases is already in progress for the Wallacean shortfall95 and could be strategically set up for other biodiversity shortfalls. We stress that such collaborations also contribute to the AI community193 by providing complex case studies that include multimodal data, long-tailed distributions, domain generalization, causal inference and other challenges. A long-term solution will be to integrate ecology into computer-science training programmes so that students trained in both specialties can speak the same language, clearly communicate issues and collectively arrive at solutions. The potential benefits of such joint training extend to related fields that face similar issues, such as Earth systems or climate sciences.

Beyond its contributions to fundamental ecology, an AI-inclusive research agenda is expected to have large follow-on benefits for policy and decision-making. Although AI is already making contributions to conservation in terms of data collection and analysis, its future contributions to fundamental ecology could greatly improve our understanding of conservation problems. As an immediate example, filling the Eltonian shortfall would provide a more-complete representation of species interactions and food webs in conservation that would help to bridge the divide between biodiversity and ecosystem function172,173,194. More-complete ecological knowledge is also predicted to greatly increase our ability to assess and monitor global indicators of the rapidly approaching 2030 GBF targets. Improved flow-through of ecological knowledge (and conservation-informed ecological hypothesis generation) to implementation of conservation strategies (Fig. 1) could generate more opportunities to tailor analyses and scenarios to specific conservation questions from academia, government, non-governmental organizations and industry, thereby setting ecologists and conservationists on a direct path to data-informed solutions.

Responses