Harvesting resilience: adapting the EU agricultural system to global challenges

Introduction

The most recent reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 2023–2027, the global COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine have re-centered the priorities of the EU’s agriculture and food security agenda. The evidence of climate change and extreme weather events compels a focus on environmental and biodiversity issues, which considerably affect agricultural production while also being significantly caused by it1. Climate and environmental concerns were already a priority in the CAP 2023-2027 and in the objectives of the European Green Deal. However, the current geopolitical landscape reinforced political discussions that emphasize the imperative for a resilient EU agricultural system that is capable of upholding food security for its population (in terms of affordability and nutrition) and contributing to the global one, improving its production efficiency while diminishing reliance on volatile global markets2.

In policy debates, the different approaches to EU agriculture have often been presented as dichotomies, such as ‘commodities versus ecosystem services’, ‘intensive versus extensive’, ‘economic versus environmental performance’ or ‘food versus fuel’3. However, the future of EU agriculture must encompass all these elements without them being mutually exclusive. To address the new challenges and to reconcile a shared vision for EU agriculture among different societal groups, the European Commission has conducted a strategic dialog with a representative group of stakeholders (more information on the strategic dialog can be found here https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/cap-overview/main-initiatives-strategic-dialogue-future-eu-agriculture_en).

EU farmers face a multitude of contrasting challenges and demands, including more frequent extreme weather events, changing crop seasonal patterns, shortages of inputs, long and vertically competitive supply chains, power disparities along the food supply chain actors, relatively high production costs and high commodity price variability, regulations to implement environmental principles and practices, complex business and administrative management, societal demand for food security and safety, and changing dietary patterns4.

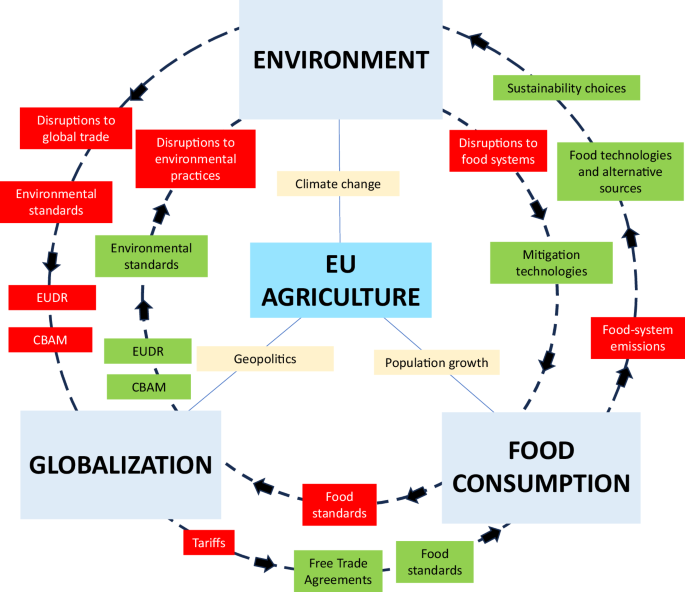

This paper analyses the main factors affecting the future resilience and adaptability of the EU agricultural system2,5; by identifying three categories of challenges and their intricate interplay (see Fig. 1): (i) the nexus of climate change, agricultural production, and environmental sustainability, (ii) food consumption patterns, and (iii) globalization dynamics. There are drivers of change that may be beyond the immediate control of decision-makers (e.g. a single government) in the short-term, particularly if tackled in isolation and outside a global coalition. These drivers notably include climate change, global population growth, and the geopolitical dynamics. Technological advancements are a mediator, facilitating adaptation to climate change and resource scarcity. Other factors are at the intersection between the three challenges. Mitigation technologies, for instance, will support fulfilling the EU food demand despite disruptions to the agricultural system induced by climate change, while consumer-driven sustainability choices, along with advancements in food technologies and alternative food sources, will help to reduce the environmental footprint of food consumption. At the interface between environmental and globalization challenges, environmental standards and EU policies such as the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) can reduce the environmental impact of trade, but at the same time they can introduce new standards that elevate transaction costs. Therefore, in Fig. 1, they appear twice, both as positive and negative dynamics, depending on the trajectory of the relationship between environmental and globalization challenges. Climate change is likely to create increasing disruptions to global trade, especially via shipping, while disruptions to input supply due to geopolitical tensions can affect EU farmers’ production methods, influencing the adoption of agro-ecological practices. Finally, in the interface between globalization and consumption, trade is a potential adaptation mechanism to reduce food security vulnerabilities resulting from climate change through improved resource allocation. Free trade agreements (FTAs) can help lower food prices for consumers, while supply chain disruptions due to geopolitical tensions and tariffs can lead to higher food prices and price volatility. Food standards can have positive effects on consumption by differentiating food quality, but at the same time, they can reduce trade and increase prices by acting as non-tariff barriers to trade6. In the following sections, we explore the interactions between these elements in greater detail, aiming to derive a possible trajectory for the future EU agricultural system.

Light blue boxes are factors affecting EU agriculture; yellow boxes are the drivers of change; green boxes indicate a positive relationship; red boxes a negative relationship. The figure is the authors’ own elaboration based on 2 and 5.

A three challenges system

Adapting agricultural production to climate change and environmental sustainability

EU agriculture faces a complex global challenge at the nexus of climate change, production dynamics, and environmental sustainability. Climate change escalates the risks for agricultural productivity and food security. At the global level, severe climate change without adaptation can reduce crop yields from 7% to 23%3,7. In addition to changing average temperature and precipitation patterns, an increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events like droughts, heatwaves, and floods significantly amplify risks to EU agricultural production8,9. Moreover, EU agricultural production is also affected by concurrent and combined hazards from climate change, such as outbreaks of invasive alien species and newly adapted pests and diseases10,11.

The impacts of climate change on the EU are heterogeneous, showing a north-south divide and a progressive northward shift in agro-climatic zones1,12. This shift might generally benefit northern European regions through higher temperatures, prolonged growing seasons, and potentially higher yields. Conversely, southern EU regions, especially in the Mediterranean, are to experience decreased crop suitability and are seriously threatened by desertification13,14,15. Moreover, despite elevated CO2 levels may favor the productivity of some crops such as wheat and rice, the response in plant biomass production may be limited or offset by factors such as nutrients and water availability, and extreme events7,16.

For EU livestock production, climate change directly affects animal health and reproduction, but it also influences the quantity and quality of feed and water17,18. This may require potential increases in the purchase of additional feed (including imports), thereby leading to higher input costs for farmers and eventually to higher dependency from imports and international market variability. In addition, heat exposure, in combination with extreme humidity levels, is among the most challenging extreme weather conditions for EU dairy production, resulting in increased cow mortality rates, reduced milk quantity, and lower protein content19.

The whole picture is further complicated by the fact that agricultural activities themselves contribute to climate change through greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and can contribute to broader environmental degradation. Globally, the agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) sector accounts for 22% of net global GHG emissions1. In a broader context, food-system emissions represent about 34% of total GHG emissions20. Therefore, effective mitigation strategies are not only necessary for reducing the production risks of climate change but also to reduce emissions and promote carbon sequestration in the EU21,22.

Technological and management measures and practices are central for addressing climate change adaptation and mitigation in the EU agricultural sector. Some of these measures and practices are already available to EU farmers, enabling them to cope with moderate climatic events, such as drought-tolerant crop varieties, water management23,24, ecological intensification practices (e.g. increasing crop diversity, adding fertility crops in rotations and organic matter), and changes in livestock feed ration or use of ventilation systems19. However, these measures may prove insufficient during extreme climatic changes, and more advanced technologies are needed to enhance mitigation in the EU. Precision and data-driven technologies offer the potential for real-time, site-specific decision-making, leveraging tools like artificial intelligence (AI), the internet of things (IoT), sensors, drones, robotics, and cloud computing. These technologies can contribute to the development of farmers’ decision support software or digital agronomy services platforms25. New Genomic Techniques (NGTs) hold promise in accelerating the development of improved crop varieties, reducing the timeline from several years to a few months with traits that can support mitigation, increased yields, or reduced natural resources use. However, while technically NGTs allow a much faster development of new varieties, regulations might significantly delay their integration into EU markets for farmers’ use. The yet uncertain EU regulatory approach to NGTs have limited seed breeding companies from investing in these technologies26. Moreover, the EU approval process for marketing and cultivation remains protracted, ranging from 8 to 12 years, depending on the crop’s characteristics, environmental impact, and safety for human and animal consumption27.

The EU adaptation to emerging invasive plants, pests and diseases might also find its own challenges. In recent years, the registration of many plant protection products has expired and not been renewed due to their harmful effects on biodiversity and non-target organisms28. This is the case of neonicotinoid and organophosphate insecticides, non-selective herbicides, and broad-spectrum fungicides (e.g. mancozeb, thiram, and propineb). While their removal from the EU market has environmental benefits, viable alternatives are not yet available to EU farmers. International agro-chemical companies are investing in the development of biocontrol agents and biostimulants. New product launches are expected over the next decade, but for EU farmers to be able to use them, the EU regulatory landscape should evolve accordingly 29.

Evolving consumption and food security

Population growth puts pressure on global food demand, but in the EU, it is the changing age structure of the population that especially influences eating behaviors and household food preferences30. There exists considerable heterogeneity in consumer preferences across EU Member States, due to cultural, geographical, and historical factors, with diets constantly evolving. Consumers in northwestern countries actively advocate for a more sustainable agri-food system and view reduced meat consumption as an integral part of a healthy diet. Conversely, these attitudes are less common in the Eastern and Southern EU regions31. Overall, drivers of change, such as changing lifestyles, health and environmental awareness, evolving eating habits, and the search for new culinary experiences, will generate new business opportunities, but also challenges for both producers and consumers4.

Health and ethical considerations (e.g. animal welfare), along with the environmental footprint of sustained animal production, are partially driving dietary shifts from animal to plant-based food in the EU30. The global market for plant-based protein products is projected to grow by 8% between 2024 to 203032. A global shift towards more plant-based diets has the potential to reduce land use for agriculture by up to 75%33. Moreover, an increased uptake of plant-based diets is associated with better health, enhanced air quality, reduced premature mortality, and substantial reductions in GHG and ammonia emissions34.

The increasing demand for plant-based products observed over recent years signals a gradual yet persistent shift from omnivorous to ‘flexitarian’ diets, i.e. a growing substitution of animal products with plant-based alternatives. Flexitarians, about 30% of EU consumers in 20212, outnumber vegans and vegetarians (a combined 7% of consumers, based on selected EU countries) and thus are more likely to drive the increased demand for plant-based foods than a complete dietary shift towards veganism2. The EU populations of all livestock species have declined over the decade 2013-2023, with goats experiencing the sharpest decline of 15%, followed by sheep (9%), pigs (6%) and bovines (5%)35. A further reduction of the EU livestock population and production is expected to continue also in the medium term, due to the lower demand for animal products, in combination with stricter environmental regulations and more efficient feed conversion ratios (which are likely to be improved via genetics and better-targeted feeding systems)2. However, there are substitution effects between different meat types. For instance, red meat intake (particularly beef and pork), associated with higher social and environmental concerns, is likely to be replaced by poultry meat2.

To address sustainability and animal welfare concerns of EU consumers, new companies and start-ups are exploring synthetic food production methods through biotechnological processes (e.g. cell cultured meat, precision fermentation). Research shows that food produced via biotechnologies can substantially reduce GHG emissions and alleviate land use pressures, but consumer acceptance and willingness to pay for these products are limited36.

Beyond sustainability concerns, EU consumers increasingly demand high-quality, nutritious food. This trend is driving the supply of functional and fortified products, especially in the dairy sector, moving along with demographic changes (e.g. aging populations, athletes, pregnant women)2.

The globalized food system: interdependencies and risks

Addressing the EU’s needs of food affordability and nutrition will require not only increased productivity but also a well-functioning trade system. Globalization presents three main challenges to EU agriculture: (i) maintaining competitiveness amidst increasingly interconnected global markets; (ii) contributing to global food security in a changing geopolitical landscape; and (iii) fostering resilience in anticipation of potential EU enlargement with competitive agrifood producers.

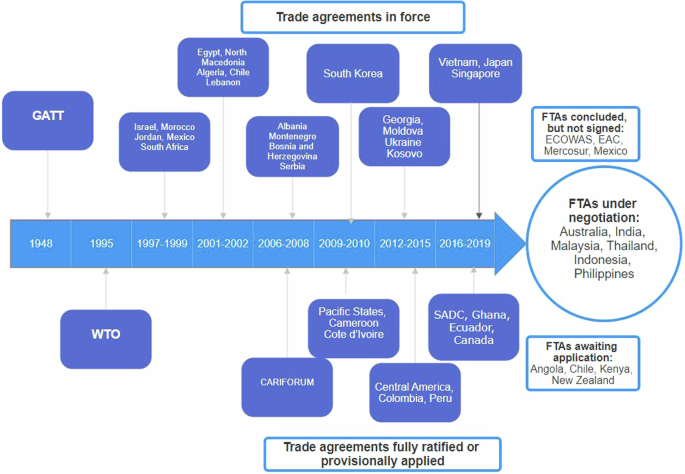

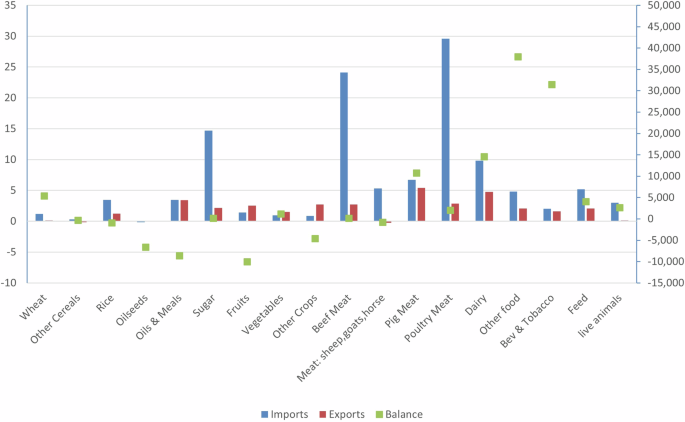

Within the EU, the Single Market facilitates diverse supply chains from various agro- and pedo-climatic zones across Europe, safeguarding the food security of the EU population, contributing to global food security and mitigating risks associated with regional production disruptions37. In 2022, extra-EU trade in agricultural products accounted for approximately 8% of the extra-EU’s overall trade (EUROSTAT figures available here), with net exports of commodities such as wheat, dairy and pig meat to many import-dependent developing countries, alongside high value food products (e.g. wine and cheese with geographical indication). The EU is one of the main driving forces of global openness and integration, and the importance of trade in agricultural products is reflected in its numerous bilateral and multilateral trade agreements signed or under negotiations (see Fig. 2). Further growth opportunities are pursued through an ambitious EU agenda of bilateral trade liberalisation, with ongoing negotiations with Australia, India, Indonesia, Mercosur, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, among others (see Fig. 3). Dairy products, pig meat and processed agricultural products, including wine and beverages, will be those sectors benefitting the most from these agreements. However, other commodities, such as beef, poultry meat, sheep meat, sugar, and rice, show the highest sensitivity to trade liberalisation, potentially leading to increased imports37. This will be particularly the case if an FTA with some of the most competitive partners like Mercosur is eventually ratified. However, the majority of currently available empirical studies on future EU FTAs do not yet assess the full impacts of policies such as the European Green Deal and the EUDR, not accounting for the short run economic costs and the expected environmental and social benefits of these policies.

The figure is the authors’ own elaboration based on https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/negotiations-and-agreements_en.

Simulations include EU FTAs with Australia, Chile, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mercosur, Mexico, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand. Trade balance is calculated as the difference between the value of exports and the value of imports. Exports and imports are measured as percentage change (left axis) while change in trade balance in million Euros (right axis) after FTAs awaiting application, concluded but not signed and under negotiation entered into force. The figure is the authors’ own elaboration based on 37.

While the EU is largely self-sufficient in agricultural products, it is dependent on import markets for key agricultural inputs such as feeds and fertilizers38. The EU livestock sector is historically dependent on imports of soybeans from Argentina, Brazil and the United States for protein-rich feed. In addition, recent events have highlighted vulnerabilities in the supply chain of mineral fertilizers whose production is concentrated in a few countries, including Russia and Belarus. Fertiliser prices are closely linked to energy prices, as especially natural gas is the main input to produce mineral nitrogen fertilizer. In 2021, various factors, such as import sanctions on Belarus and Russia, economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, soaring energy prices (which led some fertilizer companies reducing their production), rising fertilizer demand and sudden policies restricting fertilizer exports (e.g. in China), led to a rapid escalation in fertilizer prices39. This prompted challenges for farmers, with many being forced to reduce fertilizer use, resulting in adverse effects on crop yields. To reduce import dependency, the EU has developed an “Open Strategic Autonomy”40 which facilitates free trade, more diversified global value chains, and promotes the domestic production of strategic raw materials or commodities (e.g. protein crops) to reduce the EU’s reliance on imports.

Finally, the landscape of EU agricultural production, international trade, and contribution to the global agri-food market could undergo a significant change with the 2023 Enlargement Package to Moldova, Georgia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and particularly Ukraine41. Ukraine, with its 41.3 million hectares of agricultural land (which is almost twice the agricultural land of Spain), of which 68% are the highly fertile black soils (chornozem), presents substantial opportunities and challenges. The enlargement would require certain adjustments to existing policies, including the EU’s CAP, as experienced in previous enlargements.

The interplay between environment, consumption, trade and policies

The trajectory of the EU agricultural landscape in the coming years largely depends on the sustainable interplay of the outlined climate change, environmental, consumption and trade dynamics.

Consumption choices, especially those geared towards sustainability, can have a strong influence on climate change mitigation in the EU agricultural sector21,42. Estimates suggest that a global shift in dietary habits from animal towards alternative protein sources could contribute up to 20% of the mitigation needed to avoid exceeding 2 °C global warming above pre-industrial levels4. Other estimates suggest that a global shift to cultured meat and microbial proteins by 2050 could save 83% of the current agricultural land, 53% of phosphorous demand and reduce the annual agriculture emissions by 52%. However, these shifts could require 33% of the global green energy supply and exceed the primary production capacities of critical materials (e.g. tellurium)43. Moreover, well-established food cultures pose acceptance challenges for dietary shifts among EU consumers30. On the production side, EU farmers could shift to substitutes for soybean feed which convert more efficiently low-value by-products into biomass, such as algae. However, the current production scale of algae-based feed is not yet capable to meet the large EU demand for protein feed44,45.

Estimates suggest that achieving both the Zero Hunger and the Paris Agreement targets simultaneously requires a 28% increase in average global agricultural productivity in a sustainable way, which is more than three times the growth rate observed during 2010-202046. However, the number of EU agricultural workers and the availability of skilled labor is declining in the EU, potentially leading to lower harvests and output quality47. While robotics and AI technologies offer potential for labor savings, upskilling the existing workforce is needed to operate them effectively. Additionally, farmers’ willingness to adopt AI is constrained by concerns of losing control over management decisions, cybersecurity risks, and data sharing also present challenges48. Furthermore, the energy-intensive nature of the new technologies will require increased energy production and investments in energy storage solutions, such as batteries, to enable extended operation times in fields. The climate change impact of robotics and AI can be reduced by powering them with renewable energy sources49.

Climate change and global trade have both direct and indirect connections. Extreme weather events can provoke disruptions in global trade in various locations or damage crucial infrastructures necessary for trade50. For example, droughts in 2023 disrupted shipping on major inland waterways in the EU and North America, impacting commodity transportation along the Rhine and Mississippi rivers, as well as through the Panama Canal. This led to elevated transportation costs, affecting EU producers and consumers50. Moreover, current trade systems generally focus on market value and economic efficiency, disregarding environmental externalities not reflected in market prices51. International trade, especially exports to Europe and China, is estimated to be responsible for 29% to 39% of deforestation-related emissions52. Conversely, trade can also optimize production by allocating it to more efficient regions, thereby conserving water and land resources53. Socially, while EU consumers benefit from food imports in a predictable and geographically uniform way thanks to lower food prices, income losses disproportionately affect EU farmers in regions highly exposed to competitive international trade54. Therefore, trade policies can complement but cannot replace efforts for local adaption measures and management strategies to improve yields and to reduce the yield gap across EU regions.

Recognizing these dynamics, the EU is implementing initiatives to improve the environmental sustainability of trade. The new EUDR, effective from January 2025, will impede imports of goods produced on deforested lands resulting from agricultural expansion. Initially, the EUDR will apply to soybean, wood, cocoa, palm oil, coffee, cattle rubber and their derivatives (e.g. leather, chocolate, tyres, furniture) with future updates of this list. While environmental benefits are expected from reducing emissions caused by EU consumption, the EUDR will have also potential global trade effects such as a reduction of the number of importers to the EU and higher prices, especially for soybean. Other initiatives are focusing on the social sustainability of trade, such as the European Parliament and Council proposal for a regulation on ‘prohibiting products made with forced labor on the EU market’, which, if enforced, can impact imports of beef, cotton, rice, palm oil, coffee, sugarcane and coffee55,56. In addition, from 2026, the EU’s CBAM aims to impose a carbon price on the emissions generated during the production of certain carbon-intensive goods that are entering the EU and have a significant risk of carbon leakage, among others including fertilizers. The CBAM will be linked to the EU Emissions Trading System, intending to make the carbon price of imports equivalent to the carbon price of domestic production.

Geopolitical tensions and global security threats have effects on trade and production, potentially affecting the sustainability of EU agriculture. The Russian war on Ukraine had immediate effects on EU and global agricultural markets, disrupting trade routes, e.g. the Black Sea, and forcing logistical reconfigurations. The recent attacks on cargo ships in the Red Sea by Houthi rebels have reduced trade volumes in the Suez Canal by about 40%, forcing exporters from all over the Mediterranean region to consider more lengthy and costly shipping routes to Asian countries50. The cumulative effect of these events induced higher volatility in production costs, especially for energy and fertilizers, and difficulties in accessing input supplies, thereby complicating production decisions, especially regarding complying with the Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions (GAEC) standards, conditional for receiving direct payments from the CAP. Consequently, temporary derogations were granted for some of these standards, with possible delays in the environmental stewardship of agricultural land. An unstable global geopolitical landscape could also have long-term effects for sustainability. The recently adopted Nature Restoration Law by the European Parliament in February 2024 sets a target for the EU to restore at least 20% of its land and sea area by 2030, including agricultural ecosystems. However, the law allows for a suspension of its measure in agricultural ecosystems in an unforeseeable, exceptional and unprovoked event outside the control of the EU, with severe consequences for the availability of land required to secure sufficient agricultural production for the EU food security57.

Policy implications of EU agricultural transformation

The adaptation of the EU agricultural system to the challenges discussed will largely depend on the EU regulatory responses to enhance the resilience of the EU agricultural sector, to promote the needed technological developments to foster its resilience, and on how the CAP will evolve in the next programming period to cope with these challenges. Both regulatory measures and the CAP will need to reconcile the dichotomic expectations for the future EU agriculture, simultaneously addressing societal demands for a sustainable agri-food system with minimal environmental footprints, and meeting the legitimate concerns of farmers and other stakeholders regarding fair global competition and access to technological advancements. For instance, despite ongoing considerations of enhancing its strategic autonomy, the EU’s demand for protein crops will likely continue to surpass domestic supplies. While societal demand for sustainability can be addressed by regulations such as the EUDR and stringent reductions in the use of agrochemicals threatening biodiversity, resolving the current regulatory uncertainties on NGTs and facilitating the dissemination of new-generation active ingredients through appropriate regulations can enhance farmers’ competitiveness, while ensuring that major exporters comply with EU standards to facilitate the import of their products into the EU market.

On the production side, a major concern among EU farmers is the growing administrative burden set by sustainability regulations and conditionality requirements58. A simplification of bureaucratic procedures is important to foster EU farmers’ acceptance of EU policymaking. Without acceptance of EU agricultural policies by farmers, there will be no policy driven adaption of the EU agricultural system. On the consumption side, EU policymakers and regulations will need to enhance the synergies between fostering the development of new and more sustainable production technologies with the willingness of EU consumers to shift to more sustainable diets.

Finally, the EU will need to uphold its pivotal role on the international stage, within multilateral and bilateral negotiations, to keep international trade of agri-food products open and fair. The EU should also deploy diplomatic actions to help maintaining open markets and avoid third countries to implement beggar-thy-neighbor policies, such as export restrictions or bans. In fact, these policies could exacerbate price volatility and negatively affect global food security59. Simultaneously, given that modern EU trade agreements already integrate rules on trade and sustainable development, their further development and enforcement should support the EU’s active role in reconciling economic with environmental and social sustainability objectives.

Responses