Health inequalities in hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in the United Kingdom: a scoping review

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a deadly cancer in the UK despite advancements in curative therapies [1]. Due to the growing burden of chronic liver disease (CLD) in the general population, HCC is becoming one of the fastest growing causes of cancer mortality [2, 3]. Concern around this evolving public health problem has stimulated national efforts to improve standards of surveillance and management of HCC [4,5,6,7]. Social determinants and health inequalities are closely linked to the development of CLD, this extends to complications of chronic inflammation and fibrosis such as HCC [8, 9]. The World Health Organization [10]) defines health inequalities as differences in health status or in the distribution of health resources between different population groups, arising from the social conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. In CLD, there is a multi-layered interaction between the aetiological causes and access to the appropriate healthcare [11]. This combines with geographical variations in socio-economic deprivation, provision of liver services and burden of disease, which all contribute to inequitable clinical outcomes [12,13,14]. The seminal Marmot Review [15] asserts that reducing health inequalities is a matter of fairness and social justice, and must focus on reducing the social gradient in health. A better understanding of how health inequalities interact with HCC outcomes for the UK population is urgently needed to inform future research and improvements to liver disease care pathways. Thus, striving for improved and equitable access to curative treatment for patients in line with the NHS Long Term Plan and Core20PLUS5 initiative [16, 17]. A scoping review was chosen to map this emergent body of literature and identify knowledge gaps [18]. The aim is to determine the extent of research undertaken, how well subgroups and regions have been represented, the methodologies used and whether they are sufficient in characterising health inequalities and their impact on outcomes across the HCC care continuum.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted in line with the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) standards, and extension for scoping reviews [19, 20]. A comprehensive database search included MedLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and Cochrane Library to identify studies published from inception until September 2023 (when the search was conducted). A search strategy using Boolean logic and MeSH terms was developed to identify studies which focused on a population of HCC or primary liver cancer (PLC); and explored the phenomenon of interest, the impact of health inequalities on outcomes including surveillance, diagnosis, treatment, and survival. To ensure inclusivity, the search strategy was not narrowed for study type or design, therefore formal use of the PICOS or SPIDER criteria was not required [21]. No limits on time, language or type of article facilitated inclusive evidence mapping. After identification and removal of duplicates, records underwent title and abstract screening, full text for reports were then assessed for eligibility. Subsequently, citation searching was performed on all included studies to identify further relevant reports. No automation tools were used. Peer-reviewed original articles were eligible for inclusion if they involved the UK population, defined as studies where the study population included individuals from the UK, even if the population also included individuals from other countries (e.g., in meta-analyses). Articles which focused on liver disease more broadly and abstracts were excluded. An R package and Shiny app was used to produce a PRISMA 2020 compliant flow diagram [22]. Study design, cohort, setting, period, dimensions of HCC care, axes of health inequality, key findings and implications were recorded and organised in a literature matrix table to facilitate data charting and synthesis. Critical appraisal was performed for all included articles with key limitations recorded in implications in the table and an appraisal of the evidence included in the discussion. The full search strategy and eligibility criteria are included in the supplementary material.

Results

The results section has been presented in terms of the study selection and relevant design parameters, followed by the axes of health inequality identified and their impact on clinical outcomes across the HCC care continuum.

Study selection

This scoping review identified 1264 records, after removal of duplicates 704 records underwent title and abstract screening. The predominant reason for screening fail was unsuitability, as per the eligibility criteria. A single report was not retrievable to assess. Subsequently, 50 full reports were assessed for eligibility and 16 new studies, and 3 reports of new studies were included (Fig. 1).

Demonstrating the flow of sources through the different phases of identification, screening, and inclusion. Reasons for report exclusion after full-text assessment are included. 19 original articles were included in this scoping review. PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, UK United Kingdom, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma.

Study design parameters

The new studies (Table 1) predominantly adopted a retrospective cohort design or nationwide population-based analysis; single studies used comparative retrospective and prospective cohorts, a prospective longitudinal design, and projected future disease burden using an age-period-cohort model respectively. Cohorts of new PLC or HCC cases were obtained through regional hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) multi-disciplinary meeting (MDM) outcomes or from national cancer registries with linked hospital episode statistics (HES) and mortality data. A single study utilised a large primary care database [12]. The methods for identifying cohorts of patients with CLD active in HCC surveillance included screening patient records for “cirrhosis”, interrogating radiology ultrasound requests and using the Hepatitis C Research UK database linked with national cancer registry data. One study generated a cohort listed for or in receipt of liver transplantation from a national registry [23]. The setting varied from single-centre to wider regions covered by a tertiary Hepatology service, to national registries and population-based data. In the latter, different combinations of nations within the UK were represented. The period across studies included data from 1968 to 2021. The study characteristics, dimensions of HCC care, axes of health inequality, key findings, and implications of new studies are presented in Table 1.

The reports of new studies (Table 2) were all systematic reviews with meta-analysis of surveillance utilisation across studies internationally, and all included a single UK retrospective cohort study [24] within the synthesis. These were therefore deemed relevant to the UK population. However, it should be noted the included studies were predominantly conducted in the USA, with fewer studies from Europe and Asia. Included studies were predominantly retrospective or prospective cohort design, with a single randomised-control trial. Cohorts were mostly of cirrhosis, but non-cirrhotic chronic hepatitis B (HBV) was also represented. Study periods spanned from 1985 to 2020. Similarly, the characteristics, dimensions of HCC care, axes of health inequality, key findings, and implications of the reports of new studies are presented in Table 2.

Axes of Health Inequality in HCC

The findings are presented as ‘axes of health inequality’, this term has been used to refer to the dimensions of individual identity, status and social position that influence health outcomes. These axes help to identify the marginalised groups that are affected by health inequalities. This concept is closely related to ‘social determinants of health’, which refers to the wider societal conditions that also shape and sustain unequal health outcomes. There are references to the wider literature where appropriate for context.

Age

There is an inverse relationship as HCC incidence increases with age but access to curative treatment diminishes [13]. Older adults are also more likely to be diagnosed with HCC through emergency presentation and in late stages, with associated reduced survival [12, 13]. In cirrhosis with cured chronic hepatitis C (HCV), increasing age may be associated with better surveillance adherence despite potential reducing benefit [25]. Across the cancer care continuum more broadly, clinical outcomes for older adults are often inferior. Treatment is complicated by the need to adapt to baseline health and performance status, which can vary widely. Higher rates of socio-economic deprivation with advancing age and barriers to accessing care, further compound health inequalities [26].

Sex

Higher incidence and mortality in males has been observed longitudinally across the UK [1, 12, 27,28,29,30,31]. This reflects global patterns of disease [32], and is largely explained by clustering of risk factors in men and differences in sex hormones [33]. In addition, hepatic iron levels are a co-factor in fibrosis progression and the relative iron deficiency observed in menstruating women appears protective, although this advantage is lost post-menopause [34].

Ethnicity

Asian and Black Caribbean ethnic minority groups are disproportionately affected with higher incidence and mortality [28, 29, 31], this is largely explained by higher viral hepatitis incidence in migrants from endemic countries but genetic differences probably have a role [35]. However, there is also a growing burden of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) across diverse ethnicities worldwide [36]. In terms of the patient journey, higher rates of emergency presentation and late stage diagnosis, and reduced access to curative treatment are observed for ethnic minority groups in the UK [12]. This may be partly due to higher rates of socio-economic deprivation [37] and greater barriers to accessing services such as cancer screening [38].

Socioeconomic status

Local socioeconomic deprivation levels are strong predictors of inequalities in health [39] and deprivation has now been linked to liver cancer mortality in the UK [40]. Ranked indices of deprivation have been used as a proxy for income level or socioeconomic status. Increasing deprivation is associated with a higher incidence of HCC and late-stage diagnosis through symptomatic routes [12, 13, 27, 29]. Variations in the HCC disease burden have been observed with higher rates in Greater Manchester and London [13], which are presumed due to a combination of higher deprivation and ethnically diverse urban populations. However, deprivation in rural communities is also well established. The highest incidence and mortality affects men in Scotland [1], which could reflect increased exposure to risk factors such as drug and alcohol use [41]. These associations tell only part of the story, the wider societal context is clearly highly relevant but has not been captured by the evidence included in this review.

Lifestyle factors and aetiology

An epidemic of lifestyle related liver disease and subsequent HCC is being driven by behaviours including high alcohol consumption, eating low quality diets, and limited physical inactivity [42, 43]. There is conflicting evidence on surveillance adherence across different CLD aetiologies [44], but particularly poor adherence has been observed in cirrhosis with cured HCV [25]. There is a concern that MASLD is underrepresented in surveillance due to a large burden of undetected disease in the community, despite being associated with developing HCC in the absence of cirrhosis [45]. In addition, ultrasound inadequacy is a growing challenge with the increasing prevalence of people living with obesity [46], and data is awaited on the use of abbreviated MRI as an alternative. Alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD) appears associated with reduced access to treatment [14], which could represent the intersection between ongoing alcohol use and systemic inequities experienced by this group.

Access to healthcare services

The geographical provision of Hepatology services across the UK is inequitable. Higher uptake of surveillance appears associated with attending Level 3 Hepatology centres [25]. In contrast, increasing travel time is associated with increased death after listing and reduced likelihood of liver transplantation or recovery [23]; it remains debated where would be the optimum site for an additional UK transplant centre to mitigate this effect. London appears to be an outlier with better access to curative treatment and improved survival [14]. This may be due to improved access to Level 3 centres and a relatively younger population with a greater viral hepatitis predominance. The barriers faced by marginalised groups in accessing HCC care pathways remain underexplored and poorly understood.

Impact on outcomes across the HCC care continuum

The impact of the identified axes of health inequality on outcomes has been presented across the HCC care continuum, from surveillance and diagnosis to treatment and survival. Findings pertinent to the UK population and healthcare system are explored in the context of the wider literature, including research performed in different healthcare systems and cultures.

Surveillance

Surveillance appears poorly targeted, inefficient, and inequitable [24, 25, 47]. This reflects a lack of resources and infrastructure nationally despite evidence demonstrating its effectiveness in improving access to curative treatment and reducing mortality [48, 49]. Poor adherence is undoubtedly undermining these benefits, but there is a lack of good quality data and monitoring in the UK [50, 51]. A limited number of single-centre retrospective studies have reported 19–76% adherence to bi-annual surveillance [24, 25, 47], and appears particularly patchy in people with cirrhosis and cured HCV, 9% across all follow-up [25]. This aligns with meta-analyses reporting 24–52% adherence across studies internationally [52,53,54]. However, the definition of adherence is heterogenous and measurement often fraught with methodological limitations; the quality of data is low and comprehensive subgroup analyses are missing.

A combination of provider factors, such as doubting effectiveness and inappropriate requesting of tests [24, 47, 50, 51], health system factors including limited capacity and complex pathways [55], and patient factors such as non-attendance and related barriers [47, 56] contribute to poor adherence with surveillance standards. Patient-reported barriers and attitudes have not been explored in a UK population but there are emerging learnings on barriers to cancer screening more widely for underserved and marginalised groups, which could be applied [38]. There can be significant misconceptions, such as surveillance not being necessary in the absence of symptoms or after normal tests [52]. Understanding of the importance of timely surveillance is likely suboptimal and requires improved patient communications [50, 51, 55]. In the USA, a strong predictor of continued surveillance is having multiple visits with a liver specialist, and there appears to be an inverse relationship between ultrasound lead time (difference between the dates it was ordered and subsequently performed) and adherence [57].

In the UK, a radiology-led automatic recall system was trialled with no benefit [24]. More widely, other interventions have been explored including focused patient education [58], and interventional surveillance programmes which employ automatic recall, mail outreach/reminders and pathway navigators [52, 53]. All demonstrate potential to improve adherence. Further efforts to design and evaluate interventional surveillance programmes are required.

Diagnosis

HCC incidence is growing in the UK [1, 27, 28, 30] and projected to have the highest average annual increase of all cancers over the next 15 years [2]. A large proportion of cases are diagnosed outside of surveillance (60%) [44], the exact reasons are unknown and require further investigation. However, there is a growing burden of undetected CLD in the general population, which requires co-ordinated efforts to improve screening and diagnosis [43]. Symptomatic presentation of HCC is common via emergency (35.6%), GP referral (31.1%) and two-week wait (11.5%) pathways [13], which are associated with a more advanced stage at diagnosis [12]. The Covid-19 pandemic had a negative impact with higher rates of emergency presentation and larger tumour diameter [59]. One study reported an early detection rate of 25.6% for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage 0-A [44]. However, there is a lack of available national data on cancer stage, liver function and performance status at diagnosis [14].

The reporting method for imaging remains largely unstandardised across UK centres [50], despite the development of tools such as LI-RADS [60, 61] which could help standardise our approach to management [4]. Liver biopsy and histopathological assessment is increasingly required to verify diagnosis in favour of reliance on radiological evidence [28]. This shift may improve access to clinical trials, experimental treatment options and personalised therapy, an area which has been lacking compared to other cancers [62].

Treatment and survival

According to a single study with data encompassing 2001–2007, access to curative treatment (ablation, resection, transplantation) appears limited (24.4%), with the majority of patients receiving no treatment at all (58.4%), and only a small proportion undergoing transplantation at any stage (5.5%) [14]. Therapeutic advances such as loco-regional and systemic therapies over the last couple of decades have resulted in only modest improvements and 5-year survival remains low (18.3%) [1]. Intersecting axes of inequality including increasing age and deprivation, ARLD, and black Caribbean and Asian ethnic groups are associated with reduced access to treatment and survival [12,13,14]. However, rates of treatment utilisation across subgroups and reasons for non-utilisation have not been established in the UK. In addition, stage-specific survival data are not available from HES or cancer registries due to a lack of granularity. Within cancer more widely, increased travel time is associated with more advanced stage at diagnosis, inappropriate treatment and reduced survival [63]. HCC treatment is centralised at specialist centres, therefore travel time may have a significant role in treatment and outcomes and needs further exploration.

Discussion

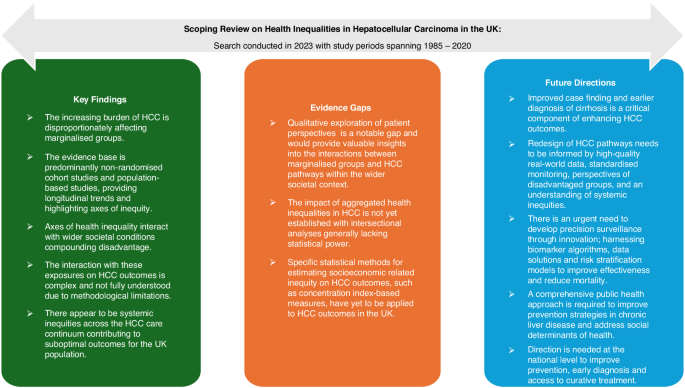

The discussion provides a synthesis of key findings, appraises the evidence – including its strengths and limitations – and outlines future directions with implications for practice, policy and research, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

A diagram presenting the key findings, evidence gaps and future directions identified. HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, UK United Kingdom.

Summary of key findings

This is the first scoping review to characterise axes of health inequality in HCC and their impact across the care continuum in the UK. The incidence and mortality of HCC are increasing and disproportionally affecting marginalised groups who remain underserved by the current healthcare system, presenting a major public health concern. The relationship between exposures and outcomes is complex. There is an interplay between individual axes of health inequality and wider societal conditions, compounded by the increasing burden of liver disease and systemic inequities in HCC care pathways. The fairness of health inequalities is nuanced, acknowledging the distinction of causal variables into ‘circumstances’ beyond individual responsibility (e.g. biological sex and socioeconomic status) and ‘efforts’ for which individuals are responsible (e.g. lifestyle factors) [64]. Regardless, the axes of inequality at play here appear to have a considerable impact with low adherence to HCC surveillance standards, late-stage HCC diagnosis, limited access to curative treatment, and low survival rates common outcomes faced by individuals. Outcomes in the UK are suboptimal in comparison to other leading healthcare systems such as Japan [65]. The axes of health inequality identified in this review have highlighted marginalised groups that experience disproportionately poor HCC outcomes. These findings have underscored the need for targeted consultation and consideration of these groups when redesigning care pathways.

Appraisal of the evidence

The evidence base is largely comprised of non-randomised cohort studies and observational epidemiological data. This has traditionally been considered a lower quality of evidence. However, it provides an appropriate lens to understand longitudinal trends and identify axes of health inequality in HCC. Several studies have attempted to explore the impact of aggregated axes of health inequality on outcomes through multivariate regression modelling [12, 13, 25, 44, 47]. However, their statistical power was generally insufficient to effectively demonstrate these intersectionalities. Statistical methods for estimating socioeconomic related inequality in health, such as concentration index based measures, have yet to be applied to HCC outcomes in the UK [66]. Qualitative studies exploring patient perspectives are a notable gap at present and would provide valuable insights into the factors that influence interactions between marginalised groups and HCC care pathways within their broader societal context. Furthermore, the meta-analyses on surveillance utilisation predominantly consider studies of non-UK populations, highlighting the paucity of UK data [52,53,54]. Therefore, differences in ethnic diversity, liver disease aetiology, and healthcare systems (such as a health-insurance model), reduce the transferability of these findings. A scoping review was adopted to map evidence and identify gaps for future research rather than answer a specific question related to HCC care. Therefore, assessing the risk of bias and certainty of evidence were not required.

Future directions

Improved case finding and earlier diagnosis of cirrhosis in the general population is a critical component of enhancing HCC outcomes. Further research is needed to evaluate the performance of current HCC surveillance and treatment pathways. High-quality data and standardised monitoring are needed to generate real-world evidence that can guide resource allocation to underserved regions and patient groups. Current surveillance strategies fail to account for individual HCC risk or competing outcomes, such as liver decompensation and death. A key priority is to develop robust, risk-based models that enable precision surveillance, enhance cost-effectiveness and reduce mortality [67]. Emerging surveillance tools such as GAAD/GALAD [68,69,70] and risk stratification models [71,72,73] move us in the right direction by incorporating age, sex and novel biomarkers within their algorithms. However, significant statistical and clinical challenges remain, and these models require external validation in the UK population before translation into routine practice [74]. To improve HCC care pathways, future efforts must prioritise incorporating the patient perspective and ensuring equitable access across underserved groups. From a policy and practice perspective, a comprehensive public health approach is critical to developing effective prevention strategies for CLD. Organisation and leadership at the national level are required to redesign HCC care pathways, reduce systemic inequities, and meet the urgent need for earlier diagnosis and more equitable access to curative treatments.

Responses