Hedgehog signaling directs cell differentiation and plays a critical role in tendon enthesis healing

Introduction

Effective attachment between tendon and bone is achieved via a specialized mineralized fibrocartilage tissue called the enthesis1,2. This functionally graded tissue is necessary for the effective transfer of force between tendon and bone tissues with vastly different mechanical properties. Unfortunately, this complex tissue is not regenerated after injury, presenting a difficult clinical challenge. For example, rotator cuff tears affect over half of the population over the age of 65 and failure rates after surgical repair of rotator cuff tears are unacceptably high, ranging from 20% in younger patients with small tears to 94% in older patients with massive tears2,3. Current treatments and repair methods do not regenerate the unique tissue architecture of the native supraspinatus tendon enthesis. At the root of this clinical problem is a scar-mediated healing response that does not recapitulate the developmental program for enthesis formation. Therefore, identification of cellular and molecular factors that drive the supraspinatus enthesis development and homeostasis is needed to motivate development of better therapeutic strategies for enthesis regeneration.

Hedgehog (Hh) signaling is one of a handful of critical signaling pathways that govern organ patterning, musculoskeletal tissue morphogenesis, and pathology-related remodeling4,5,6. In the canonical Hh signaling cascade, Hh ligands bind to the suppressor Patched 1 (Ptch1), which results in the activation of the transducer Smoothened (Smo). Smo triggers a downstream signaling cascade that includes activating or de-repressing transcription factors such as the GLI-Kruppel family members Gli1, Gli2, and Gli36,7. Hh signaling is necessary for the supraspinatus enthesis formation and Gli1 marks an enthesis stem cell population2,5,6,8,9,10. Gli1-lineage cells populate and establish the mature enthesis and deletion of Smo at the enthesis results in mineralization and biomechanical defects5,6,8,11,12. Gli1-lineage cells contribute to better healing in models of neonatal injury and in adult cell transplantation studies8,9. Furthermore, Hh signaling is activated during the healing processes after rotator cuff repair or ACL reconstruction13,14. Pharmacologic upregulation of the Hh signaling pathway at the injured enthesis increases fibrocartilage formation, mineralization, and mechanical properties, but disrupted Hh signaling via Smo deletion in tendon and enthesis leads to impaired healing responses of the injured enthesis, reflected by decreased cellularity, reduced extracellular matrix deposition, and mineralization9,15. This prior evidence motivates Hh signaling as a therapeutic target for enthesis regeneration. However, activation of Hh signaling may also lead to negative side effects such as fibrosis and heterotopic ossification. The available evidence shows that perivascular Gli1+ progenitors in the injured kidney, lung, liver, and heart serve as a major cell origin of myofibroblasts and give rise to undesired fibrotic tissues16. Gli1-lineage cells are also involved in endochondral heterotopic ossification of muscles and upregulation of Hh signaling leads to heterotopic ossification in tendon via enhancing cell chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation17,18. Therefore, there remains a gap in knowledge regarding the cellular mechanisms and the necessity and sufficiency of Hh signaling for enthesis healing.

In this study, we explored intercellular communication between enthesis Gli1-lineage cell clusters, as identified by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis. We found strong cell-cell interactions among Gli1-lineage cells mediated by signaling pathways such as Mk (midline), SPP1 (secreted phosphoprotein 1), FGF (fibroblast growth factor), EGF (epidermal growth factor), and PTH (parathyroid hormone) ligand-receptor pairs; these pathways have been reported to regulate chondrogenesis and osteogenesis19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Motivated by these results, we then evaluated the role of Hh signaling during enthesis healing via experiments of activating and deleting the Hh target genes in enthesis Gli1-expressing stem cells and their progeny. We found that activation of Hh target genes enhanced enthesis healing by promoting fibrocartilage deposition and then mineralization, demonstrating that Hh signaling is sufficient to drive enthesis formation. We also found that the removal of Smo to inactivate Hh target genes dramatically impaired enthesis healing, demonstrating that the Hh signaling is necessary for enthesis formation. Analysis of cell-cell communication and immunohistochemistry implied that improved healing is driven by Hh-directed enthesis cell differentiation.

Results

Gli1-lineage cells have strong internal cell-cell interactions during enthesis development

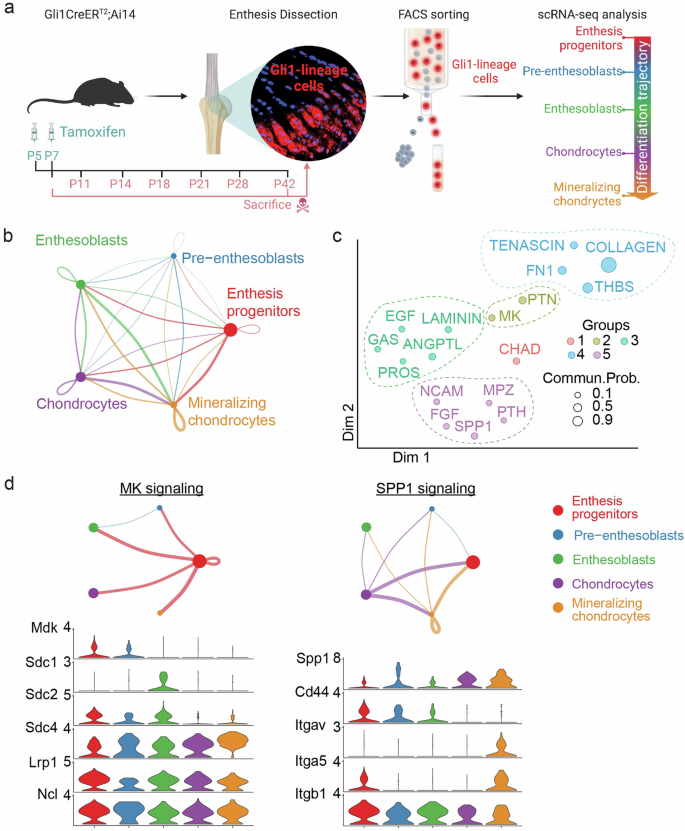

In a prior study, Gli1-lineage cells (i.e., cells that were Hh responsive) of supraspinatus tendon entheses were collected from Gli1CreERT2;Ai14 reporter mice, sacrificed at different postnatal time points (P7, P11, P14, P18, P21, P28, P42) (Fig. 1a)8. Cells were then processed for scRNA-seq analysis to delineate their differentiation path and cell-cell communication patterns. Gli1-lineage cells across postnatal time points were clustered into 5 cell subpopulations, based on their transcriptomic signatures. Clusters defined cellular differentiation states, from enthesis progenitors, to pre-enthesoblasts, enthesoblasts, chondrocytes, and finally to mineralizing chondrocytes (Fig. 1a)8. This analysis also revealed the differentiation trajectory of Gli1-lineage cells and validated the stemness of Gli1-lineage progenitors using in vivo and in vitro approaches. These cells differentiated and settled into a spatial gradient of cell phenotypes to build a functionally graded enthesis1,2. The carefully orchestrated spatial organization of the enthesis suggests that the different enthesis cell types derived from Gli1-lineage cells might interact with each other to form the enthesis. Therefore, we further analyzed our recently published single-cell transcriptomic data8 using CellChat to infer intercellular communication between the 5 cell subpopulations derived from Gli1-lineage cells6,7,8,26. Strong interactions, reflected by the thickness of the line widths connecting cells (Fig. 1b), were found between subpopulations of Gli1-lineage cells (e.g., enthesoblasts and mineralizing chondrocytes, enthesis progenitors and mineralizing chondrocytes). The strong communication between enthesis Gli1-lineage cell types suggested that cell differentiation might be regulated by Hh signaling and that several ligand-receptor pairs potentially regulated the formation of the enthesis cell phenotype spatial gradient. Clustering the communication networks revealed several functional groups, including matrix deposition, bone-regulated growth factors, chondrocyte function, and osteoblast function (Fig. 1c). MK (midkine), SPP1 (secreted phosphoprotein 1), and PTN (pleiotrophin) signaling networks were identified to mediate osteoblast activity and mineralization (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Fig. 1). Enthesis progenitors were inferred as the major senders of MK and PTN signaling. FGF and EGF growth factor signaling networks were also found to potentially contribute to enthesis mineralization, consistent with the observation of mineralizing chondrocytes as the major senders of FGF and EGF signaling networks. Interestingly, prior work has shown that Hh and PTH signaling networks form a growth-restraining feedback loop to regulate chondrocyte differentiation in the growth plate during endochondral ossification8. Considering that the enthesis is often described as an “arrested growth plate”6, the PTH signaling network was also identified in Gli1-lineage cells, with their subpopulation of chondrocytes as the major senders. This indicates that Hh and PTH signaling networks might interact similarly to the growth plate for controlling enthesis maturation and mineralization, warranting further evaluation in future studies. We also identified a novel signaling network, GAS (growth arrest-specific genes), for which enthesis progenitors were identified as the receivers from enthesoblasts and chondrocytes. Although the role of GAS has not been explored during enthesis development, prior literature suggests that mature enthesis cells might use this signaling as feedback to mediate progenitor differentiation9.

a scRNA-seq experimental design (created with BioRender.com). b Ligand-receptor interactions among Gli1-lineage cell subpopulations (the thickness of the line indicates the strength of the interaction). c Signaling pathways grouped based on their functional similarity. Each dot with an associated color indicates a communication network of one signaling pathway. The dot size represents the overall communication probability. d Inferred signaling networks and highest expression of their ligands for different cell subpopulations.

Activation of Hh target genes during postnatal development causes abnormal structure, composition, and mechanical function of the enthesis

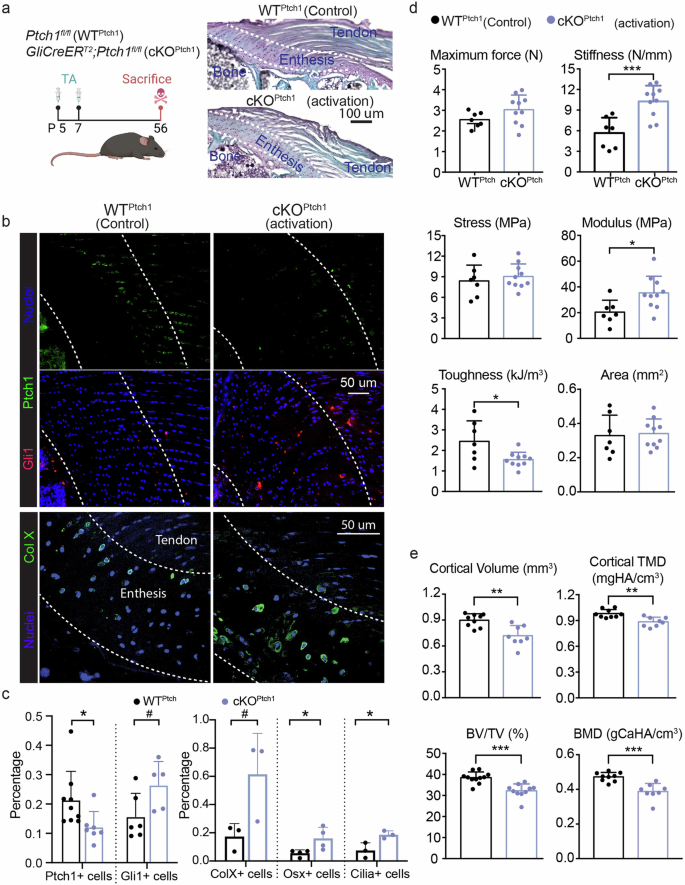

To determine how activation of Hh target genes in the postnatal supraspinatus enthesis affects enthesis formation and mineralization, we induced activation of Hh target genes in Gli1+ cells (i.e., enthesis progenitors) at postnatal day 5 (P5) by deleting Patched1 (Ptch1), which works as the suppressor of Hh signaling (GliCreERT2; Ptch1fl/fl mice, cKOPtch1, Fig. 2a). We confirmed the efficiency of activation of Hh target genes caused by Ptch1 deletion using immunohistochemistry. Due to the small size, mineral content, and paucity of cells in enthesis tissues, it is challenging to isolate enough enthesis Gli1-lineage cells for gene expression analysis and validation of deletion efficiency. Furthermore, previous experience indicated that qPCR examination of the entire tendon enthesis would mask the effects of Ptch1 deletion since the mouse model only targeted the very small population of Gli1+ stem cells5. Therefore, immunohistochemistry was performed to determine knockout efficiency across the supraspinatus enthesis using commercially-available antibodies for Ptch1 and Gli1 with the validated specificity and quality. Ptch1 deletion caused a 48% decrease in Ptch1 expression compared to wildtype (WTPtch1) mice (Fig. 2b, c). Consistent with this, Ptch1 deletion caused a 73% increase in Gli1 expression compared to WTPtch1 mice.

a Experimental design and representative histological images of Ptch1 wildtype (WTPtch1, Ptch1fl/fl or Ptch1fl/wt mice) and cKOPtch1 (GliCreERT2;Ptch1fl/fl mice) entheses (created with BioRender.com). b Representative confocal micrographs of tendon entheses (the regions between the dash lines), showing expression of Ptch1, Gli1, and collagen X (Col X). c Percentage of cells with Ptch1, Gli1, Col X, osterix (Osx), and cilia, normalized by the total number of enthesis cells evaluated from the confocal micrographs above. d Biomechanical properties (e.g., cross-section area, maximum force, stress, stiffness, modulus, and toughness) of WTPtch1 and cKOPtch1 entheses. e Cortical and trabecular bone qualities of humeral head. BV/TV, the ratio of bone volume to tissue volume; TMD/BMD, tissue/bone mineral density. Male and female mice from at least three independent litters were used and a two-tailed t-test was used to compare genotypes (0.05 <#p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) Data points represent biologic replicates..

Entheses with misaligned cells were observed in GliCreERT2;Ptch1fl/fl (cKOPtch1) mice (Fig. 2a). Activation of Hh target genes resulted in higher numbers of enthesis cells expressing collagen X (a hypertrophic chondrocyte marker), Osx (an osteoblast-specific transcription factor), and primary cilia (a Hh regulator) (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. 2). These results indicate that activation of Hh signaling in the enthesis promoted chondrogenesis and osteogenesis. Compared to WTPtch1 mice, entheses of Ptch1 conditional mutant had higher stiffness and modulus, but lower toughness (Fig. 2d). This mechanical behavior is consistent with increased mineralization in the enthesis fibrocartilage, which is expected to produce a stiffer but more brittle tissue. In contrast, the morphology of the bone in the cKOPtch1 humeral head underlying enthesis, including cortical volume, cortical bone density, trabecular bone volume, and trabecular bone density, were significantly lower than those of WTPtch1 mice (Fig. 2e). Since Gli1-expressing cells exist in both the periosteum and the growth plate, activation of Hh target genes may have led to aberrant remodeling of the humeral head of Ptch1 mutants20,27.

Activation of Hh target genes improves enthesis healing

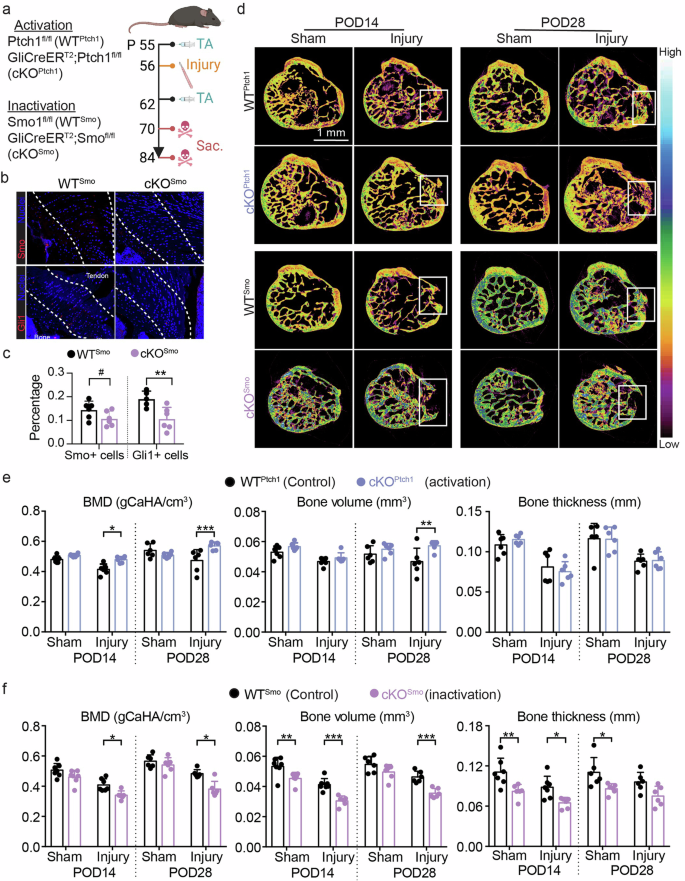

Enthesis injuries were created in adolescent mice following our previously established methods8,9. To determine the role of Hh signaling on enthesis healing, we developed transgenic mice with inducible activation and deletion of Hh target gene, respectively. Hh signaling was controlled in Gli1+ (i.e., Hh-responsive, enthesis resident) cells, allowing for the exploration of a putative cell-autonomous mechanism of regulation of Hh signaling in healing entheses (Fig. 3a). Since Gli1 is an effector of Hh signaling and Ptch1 a repressor of Hh signaling, tamoxifen injection induced Cre recombination in cKOPtch1 entheses and activated Hh target genes. Similarly, since Smo is a transducer of Hh signaling, tamoxifen injection induced Cre recombination in GliCreERT2; Smofl/fl (cKOSmo) entheses and inactivated Hh signaling. In both cases, only Hh-responsive cells were affected, allowing us to evaluate the targeted manipulation of endogenous progenitors for tissue healing. Lineage-tracing using Gli1CreERT2; Ai14 reporter mice demonstrated Gli1-lineage cells across the enthesis (Supplementary Fig. 3). Of note, the original postnatal enthesis Gli1+ stem cells, which differentiate to build the mineralized fibrocartilage of the mature enthesis, do not participate in the healing process9. Thus, we did not include a lineage-tracing experiment in our knockout mouse models to examine the contribution of Gli1-lineage cells. Tamoxifen-induced Ptch1 deletion in cKOPtch1 mice successfully activated Hh target genes by increasing Gli1 expression, as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2b, c). Similarly, tamoxifen-induced Smo deletion in cKOSmo mice successfully inactivated Hh target genes by decreasing Gli1 expression (Fig. 3c). Approximately 69% and 52% of cKOSmo enthesis cells expressed Smo and Gli1, respectively, compared to wildtype (Fig. 3c). Since the literature and our published data demonstrate that a mature, compositionally graded enthesis is formed by 8 weeks postnatally28,29,30 and the location of Gli1-positive cells is not expected to change significantly after 8 weeks5,9, we decided to use 8-week old knockout mice for evaluating impacts of Hh signaling on enthesis healing. However, it would be valuable to evaluate the regulation of Hh signaling on healing entheses of mice older than 12 weeks.

a Experimental design (created with BioRender.com). b Immunofluorescence staining of intact enthesis tissues from P84 Smo wildtype (WTSmo, Smofl/fl or Smofl/wt) and cKOSmo (GliCreERT2; Smofl/fl) mice with tamoxifen injected at P56. The regions between the two white lines indicate the entheses, used for the following quantification. (c) Quantification of Smo and Gli1 expression in enthesis tissues. d Representative μCT sections of injured entheses from Ptch1 wildtype (WTPtch1, Ptch1fl/fl or Ptch1fl/wt), cKOPtch1 (GliCreERT2; Ptch1fl/fl), Smo wildtype (WTSmo, Smofl/fl or Smofl/wt), and cKOSmo (Gli1CreERT2; Smofl/fl) mice at both post-operative day 14 (POD14) and POD28. The white boxes highlighted the injured enthesis regions used for measuring mineralization. e Mineralization of injured enthesis regions from WTPtch1 and cKOPtch1 quantified from the μCT data in (c). f Mineralization of injured enthesis regions from WTSmo and cKOSmo quantified from the μCT data in (c). The white rectangles in the μCT images identify the injured regions; The color bar shows mineral density for the lowest to highest. For C, cKOSmo was compared to WTSmo using two-tailed t-tests. For E-F, ANOVAs were performed for the factors genotype and time followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests when appropriate. 0.05 < #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Male and female mice from at least three independent litters were used. Data points represent biological replicates.

Mineralization was evaluated in healing entheses using µCT imaging and morphometric analysis. Based on representative images, more tissue with higher density filled the injured regions in the entheses of Ptch1 mutants (cKOPtch1) at both post-operative day 14 (POD14) and POD28 compared to WT and Smo mutants (cKOSmo) (Fig. 3d). Compared to WTPtch1 controls, activation of Hh target genes caused significantly increased mineral density, volume of mineralized tissues, and thickness of mineralized tissues in injured enthesis regions (Fig. 3e). In contrast to WT controls, loss of Smo caused significantly decreased mineral density and volume of mineralized tissues (Fig. 3f). These data demonstrate that Hh signaling of enthesis cells regulates mineralization of healing entheses.

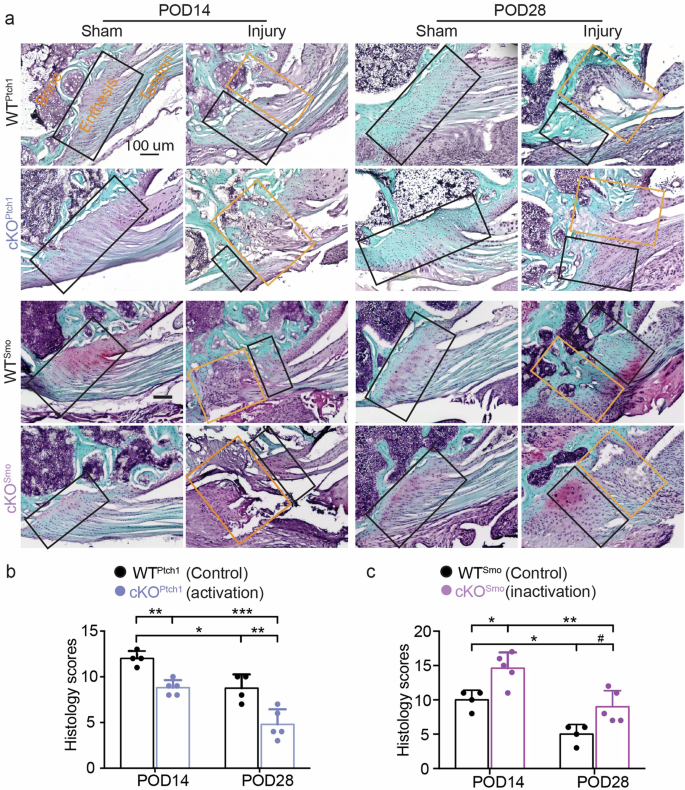

Enthesis fibrocartilage remodeling during healing was examined by analyzing Safranin O-stained histologic sections. At POD14, cKOPtch1 entheses had more fibrocartilage-like matrix (stained red) filling the injured region, with more cells, compared to WTPtch1 entheses, which had little to no matrix filling the injured region (Fig. 4a). At POD28, WTPtch1 healing entheses had increased cellularity, with disorganized immature matric filling the injured region, compared to cKOPtch1 entheses at this timepoint with fibrocartilage forming at the injured enthesis and bone-like matrix (stained blue) in the region adjacent to the injury. Consistent with our previous findings9, deletion of Hh target genes in cKOSmo entheses impaired fibrocartilage formation and resulted in lower cellularity at the healing entheses at POD14. injured entheses from Smo mutants at POD28 also showed remarkably disconnected bone-enthesis interfaces and disorganized collagen fibers. Enthesis healing was also evaluated using standardized grading criteria that considered fibrocartilage deposition, cell infiltration, enthesis integrity, and underlying bone formation8. The histology score demonstrates healing outcomes, with intact healthy enthesis defined as a score of ‘0’. In all cases, the healing enthesis at POD14 had a higher histology score than the corresponding entheses at POD28, demonstrating the progression of healing with time (Fig. 4b, c). Ptch1 mutants showed significantly lower histology scores than their WT littermates, as reflected by more organized fibrocartilage-like matrix filling the injured gap and greater mineralized tissues underlying enthesis. In contrast, Smo mutants showed significantly higher histology scores. These results support that Hh signaling is necessary for structural and composition remodeling of the injured entheses.

a Representative histological images of injured entheses from WTPtch1, cKOPtch1, WTSmo, and cKOSmo mice at both POD14 and POD28. (b) Histological scoring of injured entheses from WTPtch1 and cKOPtch1 evaluated from the images in (a). c Histological scoring of injured entheses from WTSmo and cKOSmo evaluated from the images in (a). The yellow and black rectangles in the histological images show injured and intact enthesis regions, respectively; the injured regions highlighted by the yellow boxes were used for histology scoring. ANOVAs were performed for the factors genotype and time followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests when appropriate (0.05 < #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Male and female mice from at least three independent litters were used. Data points represent biological replicates.

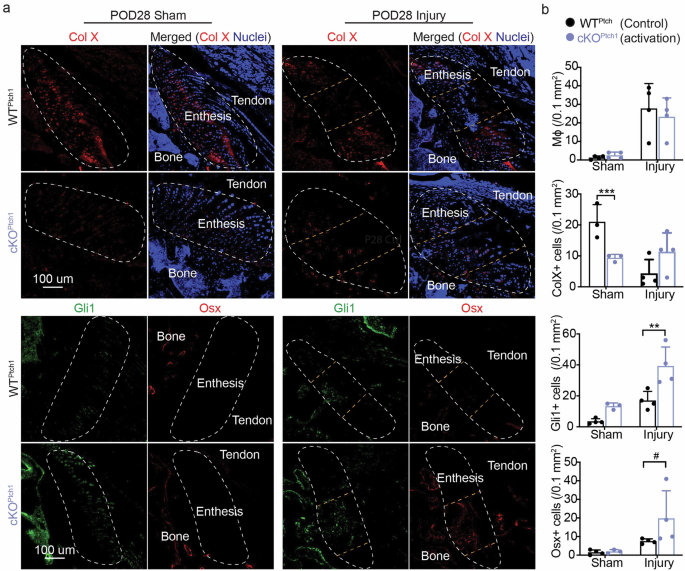

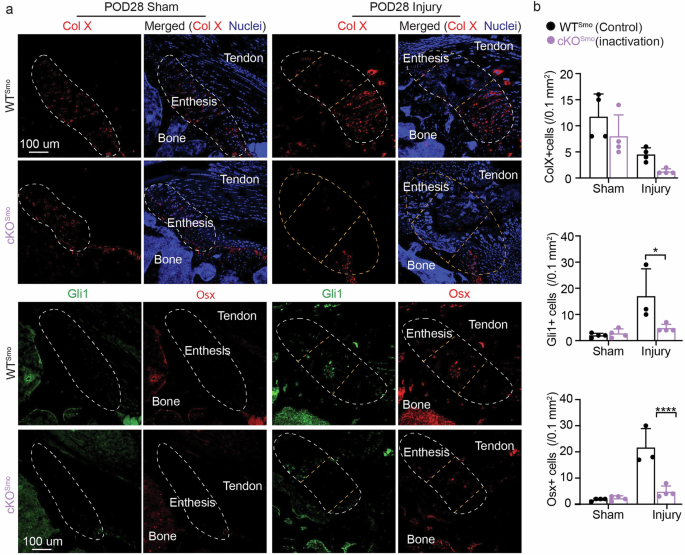

Hh signaling regulates cellular phenotypes during enthesis healing

To further determine how Hh signaling contributes to better healing, the cellular phenotypes at the healing entheses were examined. Immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate infiltration of macrophages (marked by F4/80, Supplementary Fig. 4) and the presence of hypertrophic chondrocytes (marked by collagen X, Col X) and cell types related with osteogenesis (marked by osterix, Osx) (Figs. 5–6, and Supplementary Fig. 5). Since the enthesis is adjacent to a bony layer, Osx expression during enthesis healing is more likely to indicate osteogenesis and bone formation than fibrocartilage deposition. Macrophage numbers were similar in WT, cKOSmo (inhibited Hh target genes), and cKOPtch1 (activated Hh target genes) mice, implying that improved enthesis healing after activation of Hh signaling was not driven by the macrophage-dominated immune response after injury (Figs. 5, 6, and Supplementary Fig. 4). As expected, Gli1+ cell numbers were increased in healing entheses of Ptch1 mutants (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 5) and decreased in healing entheses of Smo mutants (Fig. 6). Similarly, when examining osteogenesis, osterix expression slightly increased in healing entheses of Ptch1 mutants (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 5) and substantially decreased in healing entheses of Smo mutants (Fig. 6). Collagen X expression was decreased in uninjured Ptch1 mutants (Fig. 5b). There were few differences in collagen X expression due to Hh signaling in healing entheses. Since Gli1-expressing cells have been demonstrated to have stem cell features5,6,8,16,27,31, these results indicate that activation of Hh signaling in enthesis Gli1-lineage cells could promote their chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation to enhance enthesis healing. Consistent with our previous results demonstrating that delivery of Gli1+ cells can enhance enthesis healing8, activation of Hh target genes promoted fibrocartilage formation and mineralization and improved enthesis healing. Of note, functional analysis has not been conducted to demonstrate improvement of mechanical properties after activation of Hh signaling. However, improved enthesis mechanical function after modulating Hh signaling by delivering Hh agonist and Hh-responsive cells in previous studies implies that targeting Hh signaling could be an effective approach for enthesis regeneration8,15.

a Representative confocal micrographs of immunolabeled collagen X (Col X as a hypertrophic chondrocyte marker), Osterix (Osx as an osteoblast marker), and Gli1 (Hh activation) in injured entheses from WTPtch1 and cKOPtch1 mice. b Quantitative analyses of the fluorescent intensities of P4/80 (macrophage marker, at POD14), Col X, Gli1, and Osx in (a). The regions circled by white lines show enthesis and the regions between two yellow lines highlight injured entheses. Male and female mice from at least three independent litters were used and a two-tailed t-test was used to compare genotypes (0.05 < #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Data points represent biological replicates.

a Representative confocal micrographs of immunolabeled by Col X, Osx, and Gli1 in injured entheses from WTSmo and cKOSmo mice. b Quantitative analyses of the fluorescent intensities of Col X, Gli1 and Osx in (a). The regions circled by white lines show enthesis and the regions between two yellow lines highlight injured entheses. Male and female mice from at least three independent litters were used and a two-tailed t-test was used to compare genotypes (0.05 < #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Data points represent biological replicates.

Discussion

An essential role for Hh signaling in enthesis formation and mineralization has been previously demonstrated5,8. A unique population of Hh-responsive Gli1+ stem cells differentiates to produce a spatial gradient in cell phenotypes that builds enthesis; ablation of these cells or knockout of the Hh signaling transducer Smo leads to substantial defects in enthesis mineralization, proteoglycan deposition, and biomechanical function. The current study demonstrated through genetically activation and inactivation of Hh target genes that Hh signaling is also necessary for enthesis healing by promoting fibrocartilage deposition and mineralization8,15. Notably, inactivation and activation of Hh target genes were achieved through deletion of the Hh signaling components Smo and Ptch1, respectively, in mature entheses of only Gli1+ (i.e., Hh-responsive) cells. Therefore, Hh signaling could modulate enthesis healing by promoting fibrocartilage deposition and mineralization. More cells expressing chondrogenic and/or osteogenic markers infiltrated the injured enthesis after activation of Hh target genes, suggesting that Hh signaling promotes cell differentiation toward the phenotypes required to rebuild the enthesis. This presumption is also supported by our previous studies, which demonstrated in vitro clonogenicity and multipotency of enthesis Gli1-expressing cells8. Furthermore, ligand-receptor crosstalk analysis inferred potential communication among subgroups of differentiated Hh-lineage cells, which requires further study to validate.

Components of the Hh signaling pathway, e.g., Ihh, Ptch1, Smo, and Gli1, are upregulated at the injured tendon and ligament entheses at both the gene and protein levels6,9,13,17, indicating that the pathway is activated by enthesis injury. In the current study, we targeted the injury-activated Hh-responsive cells at the rotator cuff enthesis using the Cre-Lox system, resulting in autonomous constitutive inhibition or activation of Hh signaling in these cells. Improved healing was seen in entheses where the activity of Hh signaling was upregulated in injury-activated Hh-responsive (Gli1+) cells, implying that this cell population is a key contributor to healing and can be stimulated via a cell-autonomous mechanism.

Activation of Hh signaling is critical for the development of many tissues and marks enthesis progenitor cells. Consistent with the wealth of knowledge about the function of Hh signaling in organ development and fibrosis, the results reported in the current study show that Hh signaling at the enthesis may specify and maintain cell stemness and mediate cell differentiation in response to injury16,32. Our previous and current findings demonstrate that enthesis injury activates Hh signaling, as reflected by the accumulation of Gli1-expressing and Gli1-lineage cells at the injury site9. Additionally, Gli1-expressing cells in the injured enthesis of Ptch1 mutants expressed the chondrogenic marker collagen X and the osteogenic marker osterix, suggesting that Hh-responsive cells have the differentiation capacity to become chondrocytes and osteoblasts during healing. In several musculoskeletal tissues, including meniscus, bone, and muscle, Gli1-lineage cells have been identified as mesenchymal progenitors and give rise to mature stromal cells27,33,34. Manipulation of Hh signaling by activation of Hh target genes, Gli1+ cell transplantation, or Hh agonist treatment demonstrates that injury activates this pathway and expansion and differentiation of Hh-responsive cells can improve enthesis healing17,27,34.

Cell-cell communication analysis of scRNA-seq data of enthesis development provided insight into cell-cell interactions among Gli1-expressing cells and their progeny. This analysis implicated crosstalk between Hh signaling and other signaling pathways that regulate chondrogenesis and osteogenesis at the enthesis. Although Gli1-expressing cells have been suggested to be tissue stem cells in our current study and in previous work5,8, it remains unclear what molecular factors mediate Gli1 stem/progenitor cells differentiating into the cell types required for building and maintaining the functionally graded tendon enthesis. The current study revealed that mineralizing chondrocytes communicated with, for instance, enthesoblasts and enthesis progenitors via FGF signaling and EGF signaling. Fgf2 expression has been demonstrated in chondrocytes and osteoblasts in adult stages and FGF signaling is found to maintain the undifferentiating and proliferative states of mesenchymal progenitor cells via inhibiting Sox9 expression23,35. EGF signaling has also been shown to preserve bone marrow stem cells and enhance their proliferation and inhibit osteoblast differentiation21,22. A similar regulatory mechanism via FGF and EGF signaling might also exist at the tendon enthesis to facilitate cell specification during development and healing. MK ligand-receptor interaction was reported here between enthesis progenitors and other Gli1-lineage progeny, suggesting a possible role of enthesis progenitors in increasing proliferation and differentiation of osteogenic and chondrogenic cells19,24. SPP1 signaling, responsible for producing osteopontin and important for mineralizing matrix, was recognized to mediate the interaction among the subpopulations of Gli1-lineage cells. The crosstalk between Hh signaling and PTH signaling has also been well appreciated to control the decision of chondrocytes to exit proliferation through a feedback loop during growth plate development20. The enthesis, often described as an “arrested growth plate”, also had cell-cell communication governed by PTH signaling6.

Hh signaling mediated differentiation of cells during enthesis development. Activation of Hh target genes showed enhanced enthesis material and structure properties, likely due to elevated chondrogenesis, including increased collagen X expression, and increased osteogenesis, including increased osterix expression. However, the quality of humeral head bone from Ptch1 mutants during development was also affected, with smaller cortical and trabecular bone volume and bone mineral density. The discrepancy in effects of Ptch1 deletion on the enthesis compared to the bone during development may be explained by the different mineralization processes of the two tissues: enthesis mineralization occurs through endochondral ossification which is arrested, with Gli1-lineage cells maintained; humeral head mineralization occurs through endochondral ossification followed by bone remodeling, with Gli1-lineage cells replaced by osteoblasts and osteocytes5.

There were several limitations to our study. First, due to the relatively shallow sequencing depth of the sequencing technique we used, expression of genes related to Hh signaling (such as Ihh, Shh, Smo, Ptch1, Gli1/2/3) was relatively low compared to some common marker genes (such as Scx, Sox9, Col I, Col II), which challenges the identification of the role of Hh signaling within enthesis cells. Second, we did not perform functional in vivo gait analysis in our transgenic mouse models. Therefore, we cannot state with certainty that the loading patterns were the same in all mouse models. However, qualitative observations did not reveal any apparent differences in mouse movements. Third, we did not examine the role of inflammatory responses in our transgenic mouse models. Immune cells have important roles in modulating tendon and enthesis responses to injury, often promoting impaired or fibrotic tissue formation36. Although similar numbers of macrophages between the entheses of injured WT, Smo mutants, and Ptch1 mutants were found, resident T cells and myeloid cells identified in the enthesis in the literature are potentially involved in the healing responses of our models29,37. We did not incorporate a Cre reporter strain in our transgenic mouse models, since our previous reports comprehensively demonstrated the location and distribution of Gli1-lineage cells in immature and mature healthy and injured mouse entheses5,9; these prior results provided sufficient evidence to identify the cell population targeted in our study. Additionally, the knockout efficiency of Smo and Ptch1 was not validated transcriptionally due to the small enthesis size and low cell density, but our immunostaining data showed correspondingly changed protein expression of Smo, Ptch1, and Gli1.

In summary, we used experiments of activation and inactivation of Hh target genes to evaluate the necessity of Hh signaling in Gli1-lineage cells for enthesis repair. The results support the premise that Hh signaling is an attractive therapeutic target for enthesis repair, especially with the ongoing efforts that have produced several small molecules that activate Hh signaling. Translational work needs to be conducted to build standardized protocols and evaluate treatment efficacy in big animal models.

Methods

Mouse models and study design

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with animal protocols approved by the Columbia University and Mount Sinai Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee. All animal study reports adhere to the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of in vivo Experiments).

C57BL/6 J mice (strain 000664), Gli1CreERT2 mice (Gli1tm3(cre/ERT2)alj/J; strain 007913), Ai14 mice (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J; strain 007914), Ptch1fl/fl mice (B6;129T2-Ptch1tm1Bjw/WreyJ; strain 030494), and Smofl/fl mice (Smotm2Amc/J; strain 004526) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. For scRNA-seq analysis of Gli1-lineage mice at different postnatal time points, Gli1CreERT2; and Ai14 mice were generated by crossing Gli1CreERT2 mice with Ai14 mice. Tamoxifen was dissolved in corn oil and these mice received 100 mg/kg body weight tamoxifen at postnatal day 5 (P5) and P7. For inactivation of Hh target genes, Gli1CreERT2; Smofl/fl mice were generated by crossing Gli1CreERT2 mice with Smofl/fl mice. These mice received tamoxifen at P56 on the surgical day and seven days after surgery to evaluate the role of Hh signaling during enthesis healing. For activation of Hh target genes, Gli1CreERT2; Ptch1fl/fl mice were generated by crossing Gli1CreERT2 mice with Ptch1fl/fl mice. These mice received tamoxifen on P5 and P7 and were sacrificed at P56 to evaluate the role of Hh signaling on enthesis development. To evaluate healing responses of the entheses of activating Hh target genes, Gli1CreERT2; Ptch1fl/fl mice received tamoxifen on the surgery day and seven days after the surgery to examine the contribution of Hh signaling to enthesis healing. All mice were maintained and handled according to approved animal protocols. All the mice were euthanized by isoflurane inhalation before outcome measurement. For each assay, both male and female mice from at least three independent litters were randomized for use. Analysis of microcomputed tomography, histology, and immunohistology were conducted by blinded researchers regarding sample genotype and treatment. All data points presented in plots represent biologic replicates.

Single cell RNA sequencing analysis

Gli1-lineage Cells from tendon entheses of Gli1CreERT2; Ai14 were isolated and prepared for scRNA-seq analyses8. After injecting with tamoxifen at P5 and P7, supraspinatus tendon entheses from Gli1CreERT2; Ai14 mice were harvested at P7, P11, P18, P21, P28, and P42, digested, filtered, and stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI8. Live Gli1-lineage cells with red fluorescence and without DAPI staining were sorted into 96-well plates, prefilled with lysis buffer for 3’-End scRNA-Seq. Following standard scRNA-seq protocols, gene expression matrix was generated, filtered, quality-controlled, integrated, clustered by representative marker genes, and visualized using the R package Seurat8. Gli1-lineage enthesis cells were extracted and integrated for cell-cell communication analysis using the CellChat tool kit7. The final analysis using scRNA-seq, shown in Fig. 1,2 was performed on samples from a recently published dataset GSE1509957.

Enthesis injury

Enthesis injury protocols were adapted from our previous study8,9. After injection with buprenorphine SR followed by isoflurane anesthesia, the upper limbs of P56 Gli1CreERT2; Smofl/fl and Gli1CreERT2; Ptch1fl/fl mice (n = 6–8 with equal females and males for each post-operative time point) were used. A small incision was made at the deltoid to visualize the humeral head and the supraspinatus tendon enthesis. A 28G needle was used to punch a hole in the middle of the enthesis in one shoulder. For the sham control, no injury was created at the supraspinatus enthesis of the other shoulder. The deltoid was repaired using 5–0 Prolene suture over the humerus and the skin was closed. Mice were euthanized at post-operative day 14 and 28.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Mouse supraspinatus tendon-bone samples were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and decalcified in buffered versenate for 21 days. The decalcified samples were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, sectioned into 6-μm-thick sections, and stained safranin O following production protocols8,9,38. All histology images were acquired on a Zeiss Axiovert microscope. The histology scoring was performed according to our previous studies8. The scoring system evaluated cellularity, cell morphology, cell orientation, collagen alignment, insertion continuity and maturity, and bone quality underlying the enthesis, based on the published approach22.

For immunohistochemistry, 2 mg/ml hyaluronidase was prepared in PBS to digest 10-μm-thick sections for 1 h and the digested sections were blocked with 15% goat serum. Primary antibodies (1:50–1:500 dilution), including Smo (LS-A2666-50, LSBio), Ptch1 (ab51983, Abcam), Gli1 (ab49314, Abcam), F4/80 (14-4801-82, eBioscience), collagen X (ab58632, Abcam), osterix (sc-393060, Santa Cruz), and acetylated tubulin (marker for primary cilia, T7451, MilliporeSigma) was freshly prepared in PBS and used to incubate sections at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with corresponding secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were washed three times by PBS and finally mounted in antifade mountant with DAPI (p36931, Invitrogen). Sections were imaged on a Nikon Ti Eclipse inverted microscope with a 60x oil or 20x objective for visualizing primary cilia and other components. Cilia was quantified by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The entire enthesis region for two sections per sample was evaluated and averaged. At least 100 cells from each section were considered and the percentage of ciliated cells and cells expressing corresponding protein were normalized by the total cell number. Image stacks were projected maximally to display as immunofluorescent micrographs. For evaluating deletion efficiency, a more focused region of the enthesis was examined, corresponding to results from lineage tracing experiments. Specifically, lineage-tracing results from the current study (Supplementary Fig. 3) and our prior report5 demonstrated that Gli1-lineage cells are concentrated in the unmineralized portion of the enthesis. Therefore, this region, corresponding to relatively round cells located near the tendon was analyzed for deletion efficiency.

Microcomputed tomography (μCT)

Bone morphometry analysis was performed on supraspinatus tendon-humeral bone samples. Samples were scanned at an energy of 55 kilovolt peaks, an intensity of 145 μA, and a standard resolution of 5 μm (Bruker Skyscan 1272). The method to quantify bone morphometry was described and shown previously22. Briefly, images were reconstructed and the humeral head bone was rotated to visualize the injured enthesis in the coronal plane. The region of interest used for bone morphometry analysis was defined in the transverse plane, taken as a cuboid (the projection of the white squares in Fig. 3d) with a fixed dimension, ranging from the beginning to the end of the injured region on the coronal plane. A segmentation algorithm (CTAn, Bruker) was performed to measure bone volume, bone thickness, and bone mineral density of the region of interest8,38.

Statistical analysis

All results are shown as mean±SD. All data points in plots represent biologic replicates. Two-tailed unpaired t-tests were used to compare cKOPtch1 to WTPtch1 (Prism, GraphPad). For injury groups, ANOVAs were performed for the factors genotype and time followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests when appropriate. Statistical parameters such as sample numbers and statistical significance are included in the figure legends. P < 0.05 was considered significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant).

Responses