Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is required for curcumin or resveratrol in exerting their metabolic beneficial effect in male mice

Introduction

Except for prescribed drugs and physical exercise, various dietary interventions were also shown to improve metabolic homeostasis [1, 2]. One type of dietary intervention is the change of dietary behaviors, such as nutritional restriction and intermittent fasting [3], while another type is the addition of chemical compounds from edible plants into the diet [4]. One category of those compounds is dietary polyphenols, with the curry compound curcumin and resveratrol, mostly found in red grapes, as two typical examples [1, 5]. Interestingly, previous observations made by our team and others have shown that both dietary polyphenol intervention and amino acid restriction target the hepatic hormone fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) [2, 3, 6, 7].

Members of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family interact with FGF receptors (FGFRs) including FGFR1, leading to complicated downstream signaling events. Due to the lack of a heparin binding domain, FGF21, FGF19 (FGF15 in rodents) and FGF23 can be released freely into the bloodstream, serving as endocrine hormones [8]. In addition to FGFRs, the obligatory co-receptor β-klotho (KLB) is also required for FGF21 to exert its metabolic functions [8]. It is generally accepted that plasma FGF21 is liver driven, although FGF21/Fgf21 mRNA expression can be detected in adipose tissues, pancreas, and elsewhere [8,9,10]. Various FGF21 analogues have been tested in pre-clinical and clinical trials for treating metabolic disorders including diabetes and fatty liver disorders [8]. The most promising effects of those “pre-drugs” are the attenuation of hyperlipidemia and the improvement of insulin sensitivity. Other investigators and our group have also reported that hepatic FGF21 expression can be regulated by glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), including both exenatide and liraglutide [11,12,13,14]. Utilizing a liver-specific Fgf21 knockout mouse model, we have demonstrated that hepatic FGF21 is required for liraglutide in improving energy homeostasis in male mice with obesogenic diet challenge, making hepatic FGF21 as a “central molecule” for both GLP-1R-based drugs and diet interventions [11]. Liraglutide treatment or curcumin intervention was also shown to attenuate high-fat-diet (HFD)-induced repression on Fgfr1, which encodes the FGF21 receptor FGFR1, or Klb, which encodes the obligatory co-receptor KLB [6, 11]. These regulatory events are commonly interpreted as the improvement of FGF21 sensitivity [6, 11].

Utilizing the hepatic FGF21 deficient mice, here we have asked a straightforward question: Whether FGF21 is also required for curcumin or resveratrol, two typical dietary polyphenols, in exerting their metabolic beneficial effects?

Materials and methods

The source of dietary polyphenols and the experimental diet

The curry compound curcumin was purchased from Organika Health Products (Richmond, BC, Canada; a 95% standardize curcumin extract) while resveratrol was purchased from Combi-Blocks (Catalog #: OR-1053, San Diego, CA, USA), as we have reported previously [5, 6]. Methods for curcumin and resveratrol intervention have been described in our previous studies [5, 6, 15,16,17,18]. Contents of experimental diets utilized in this study are shown in Supporting Table 1.

Animals and animal experimental design

Six-week-old wild type C57BL/6J mice, liver-specific Fgf21 knockout (lFgf21-/-) mice and the wild type littermate controls (Fgf21fl/fl) were utilized in this study. lFgf21-/- mice were generated by mating Fgf21loxP (Strain #: 022361, Jackson lab) with Alb-Cre mice (Strain #: 003574, Jackson lab) as we have reported previously [11] (Figure S1A). Mice were maintained at ambient room temperature and relative humidity of 50%, with free access to food and water under a 12 h light:12 h darkness cycle (n = 4–5 per cage). At the end of the experimental period, mice were fasted overnight before being euthanized with CO2 treatment followed by cervical dislocation. The animal experiments and protocol were approved by the University Health Network Animal Care Committee (AUP 2949.18) and were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care. For curcumin intervention, 6-week-old male mice were fed an high fat high fructose diet (60% HFD with 20% fructose, HFHF, n = 5) with or without curcumin (4 g/kg diet, n = 5) for 15 weeks, as we have reported previously [6]. For resveratrol intervention, 6-week-old male mice were fed on an LFD (n = 5 for C57BL/6J; n = 4 for Fgf21fl/fl), obesogenic diet (HFD [n = 5 for C57BL/6J] or HFHF diet [n = 5 for Fgf21fl/fl, and n = 6 for lFgf21-/-]) with or without resveratrol (0.5% of the diet [n = 5 for Fgf21fl/fl, and n = 6 for lFgf21-/-]) for indicated period of time [5]. Mice were randomly assigned to either receive or not receive dietary intervention. Based on our animal protocol, mouse with serious body weight loss or shown “sickness” symptoms will be excluded from the study. For the current study, no mice or data points were excluded.

The generation of Fgf21fl/fl and lFgf21-/- mice were verified by genotyping. For data presented in Figs. 1–2, male and female Fgf21fl/fl and lFgf21-/- littermates were fed with LFD. Metabolic tolerance tests were conducted at the week of 8th, 10th, 12nd and 15th for glucose tolerance test (GTT), pyruvate tolerance test (PTT), insulin tolerance test (ITT) and fat tolerance test (FTT), respectively. Prior to fat tolerance test (FTT), the blood triglyceride (TG) levels at random or fast state were assessed at the week of 14th. For data presented in Figs. 3–6, only male Fgf21fl/fl and lFgf21-/- littermates were examined.

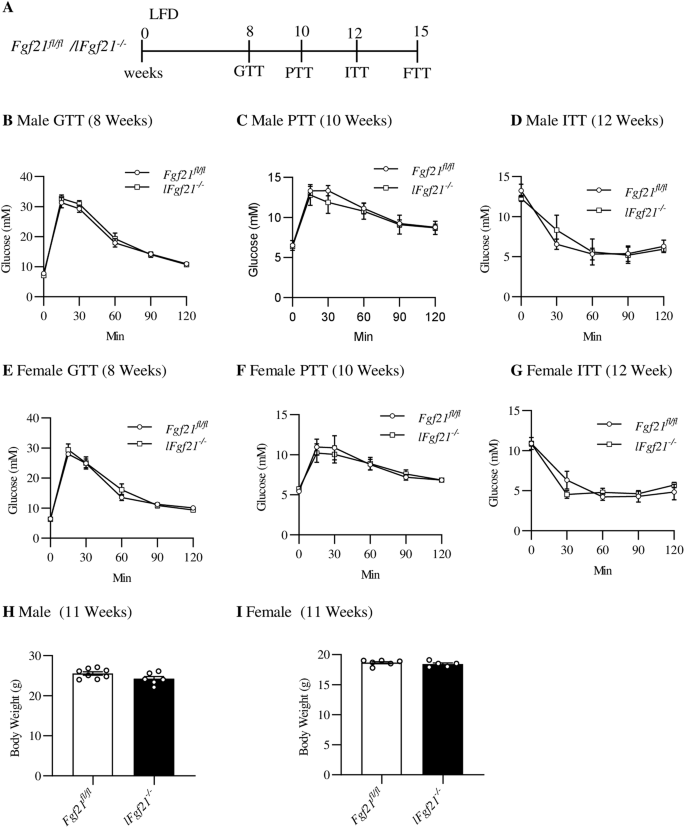

A Illustration of the animal experimental timeline. B–D Glucose level during tolerance test in adult male mice, Glucose tolerance test (GTT) at the age of 8 weeks (n = 6 for both Fgf21fl/fl and lFgf21-/-) (B). Pyruvate tolerance test (PTT) at the age of 10 weeks (n = 4) (C). Insulin tolerance test (ITT) at the age of 12 weeks (n = 4) (D). E–G Glucose level during GTT in adult female mice, GTT at the age of 8 weeks (n = 6 for Fgf21fl/fl, n = 5 for lFgf21-/-) (E). PTT at the age of 10 weeks (n = 3) (F). ITT at the age of 12 weeks (n = 3) (G). Body weight in both male (H) and female mice (I). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

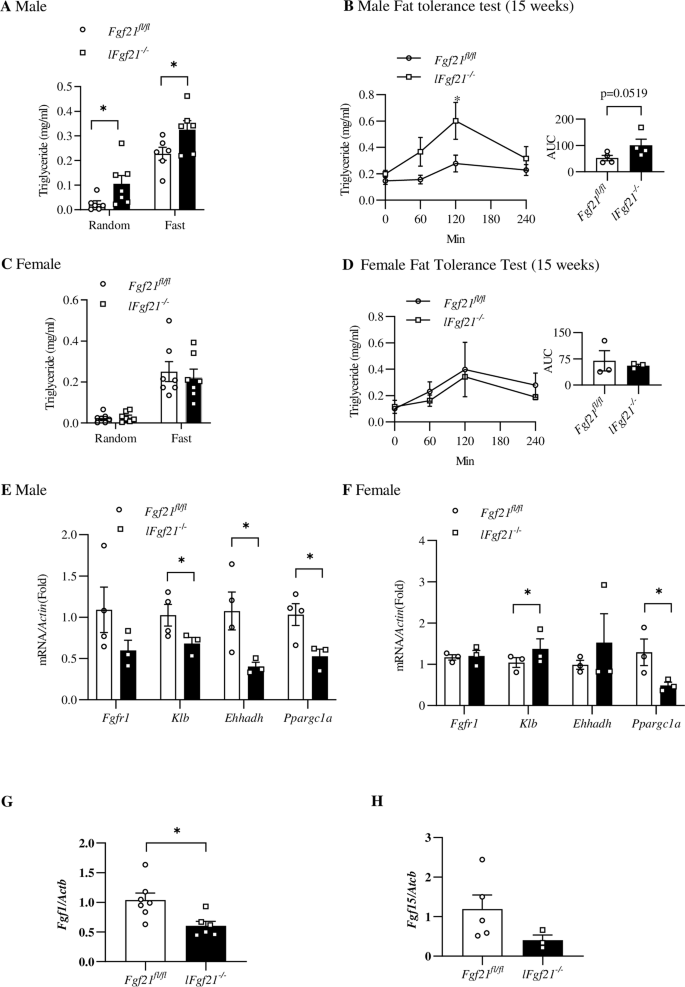

A Random and fasting serum TG levels in indicated adult (8 weeks) male mice (n = 6 for both groups). B Postprandial TG levels during fat tolerance test (FTT) in male mice at the age of 15 weeks (oral gavage 1% olive oil). C Random and fasting serum TG levels in adult female mice (n = 7 for both groups, 8 weeks). D Postprandial TG levels during FTT in female mice at the age of 15 weeks. Comparison of expression levels of hepatic genes that encode FGFR1 (Fgfr1) and KLB (Klb), as well as two FGF21 downstream effectors, peroxisomal L-bifunctional enzyme (Ehhadh) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (Ppargc1a) in male (E) and female mice (F). Fgf1 (G) and Fgf15 (H) expression levels in the liver of Fgf21fl/fl (n = 4–7) and lFgf21-/- (n = 3–6). mice. AUC, area under the curve. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

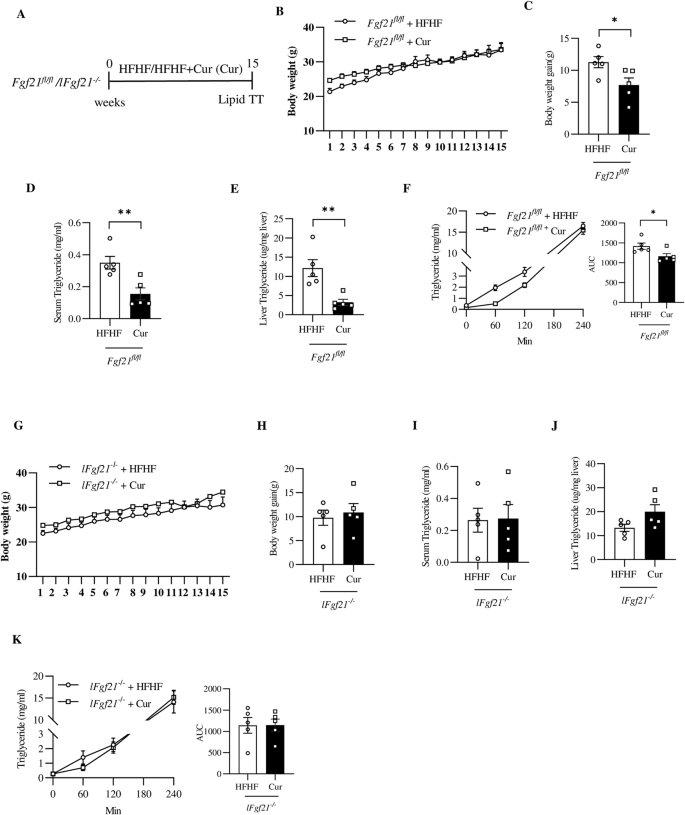

A Illustration of the animal experimental timeline. B Body weight of Fgf21fl/fl mice during the experimental period. C Body weight gain of Fgf21fl/fl at the end of the 15th week after overnight fasting. Serum (D) and hepatic (E) TG levels in Fgf21fl/fl mice. F FTT and AUC. Overnight fasted Fgf21fl/fl mice were (intraperitoneal, i.p) injected with 1 g/kg poloxamer 407 to block lipolysis. Blood samples were then collected from tail vein at indicated time for TG level measurement. G Body weight of lFgf21-/- mice during the experimental period. H Body weight gain of lFgf21-/- mice at the end of the 15th week after overnight fasting. I Serum TG level of lFgf21-/- mice. J Hepatic TG level in the lFgf21-/- mice. K FTT and AUC for overnight fasted lFgf21-/- mice. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5 each group). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

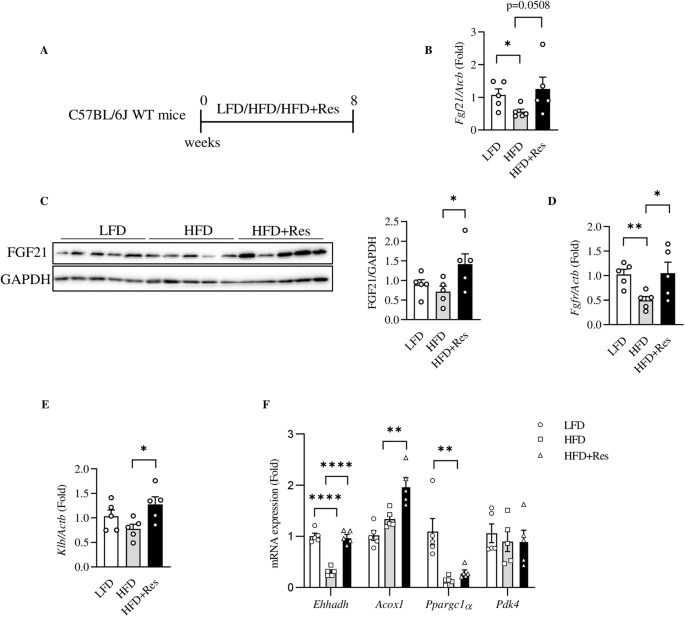

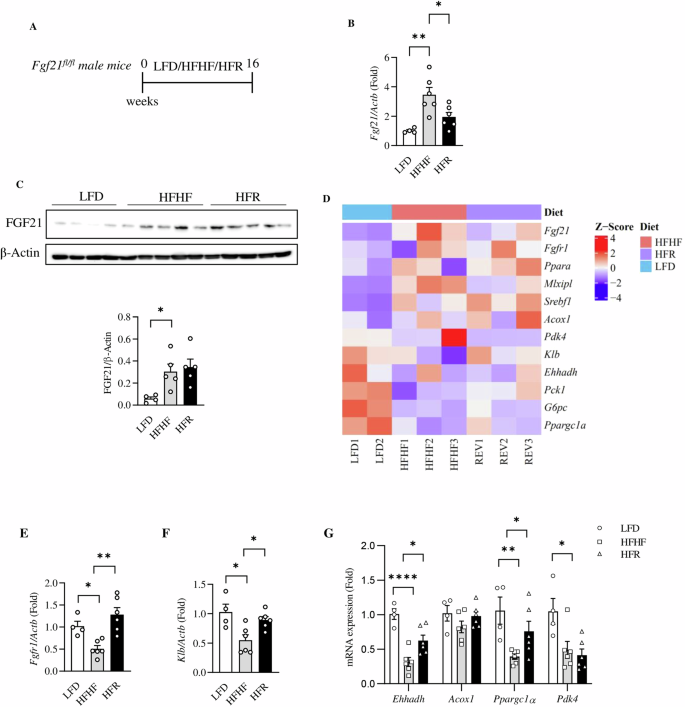

A Illustration of the animal experimental timeline in male C57BL/6J mice. B Hepatic Fgf21 level in indicated group of mice. C Hepatic FGF21 protein level. The right panel shows the densitometric analysis results. D, E Liver expression levels of Fgfr1 and Klb in indicated group of mice. F Liver expression levels of Ehhadh, Acox1, Ppargc1a and Pdk4 in indicated group of mice. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001.

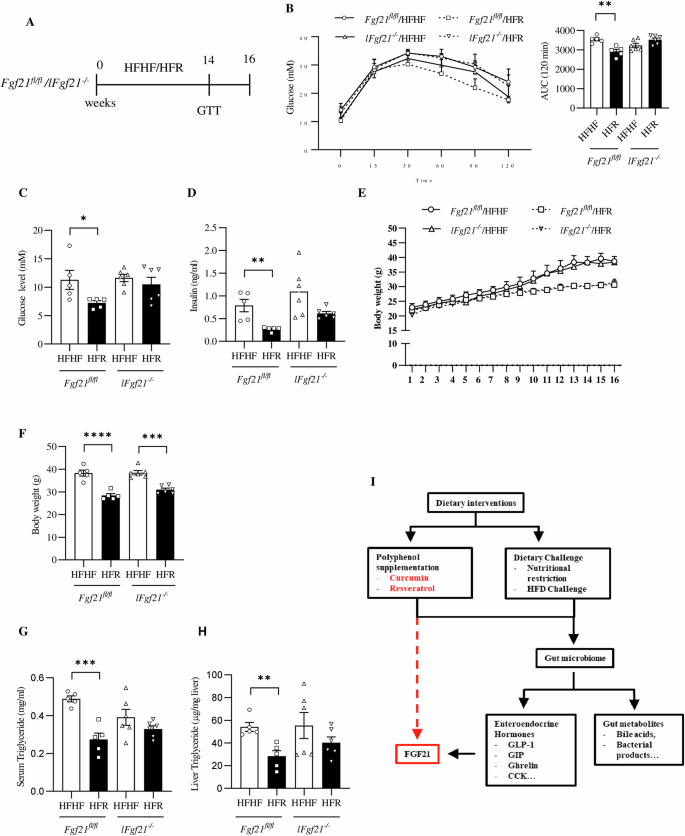

A Illustration of the animal experimental timeline in Fgf21fl/fl mice [n = 4 for LFD group, and n = 6 for HFHF and HFR groups]. B Hepatic Fgf21 level in indicated group of mice. C Hepatic FGF21 protein levels. The bottom panel shows the densitometric analysis results. D Heat map shows comparison of selected FGF21-related genes among mice fed with LFD, HFHF and HFR diet. E–G qRT-PCR assessment on hepatic expression of indicated genes in LFD (n = 4), HFHF (n = 6) and HFR (n = 6) mice. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001.

A Illustration of the animal experimental timeline. B Blood glucose level and AUC during glucose tolerance test of Fgf21fl/fl and lFgf21-/- mice. C Fasting glucose level at the end of the study. D Serum Insulin level. E Body weight during the experimental period. F Body weight gain at the end of the 16th week after overnight fasting. G Serum TG level of indicated group of mice. H Hepatic TG content of indicated group of mice. I Diagram shows our view that it is gut microbiome that mediates functions of dietary interventions, involving the hepatic hormone FGF21. Dietary intervention including dietary polyphenol supplementation or dietary behavioral changes alter gut microbiome composition and diversity. This in term triggers organ-organ crosstalk involving the gut-brain, gut-liver or other axis, with altered entero-endocrine hormone (GLP-1, GIP, and others) production and function, and altered levels of gut metabolites (bile acids and others), leading to the alteration on hepatic FGF21 production and sensitivity. Hence, without hepatic FGF21, dietary intervention cannot exert its metabolic beneficial effect. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5 for Fgf21fl/fl, and n = 6 for lFgf21-/-). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001.

Metabolic tolerance tests and TG measurement

Methods for GTT, PTT and ITT have been previously presented [19]. For intraperitoneal GTTs and PTTs, both male and female mice were fasted for 16 h prior to the intraperitoneal injection of glucose (2 g/kg body weight) or pyruvate (2 g/kg body weight). For ITTs, male and female mice were fasted for 4 h prior to the injection of insulin (0.5 U/kg body weight). Blood glucose levels were determined at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. We adopted the method by Gniuli et al. for conducting FTT [20]. Briefly, mice were fasted overnight prior to oral gavage of 1% olive oil of body weight. Blood was collected from tail vein at 0, 1, 2 and 4 h for TG measurement. To determine TG produced by the liver (lipid tolerance test), mice fasted overnight were injected intraperitoneally with poloxamer 407 (Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog #: P2443) to block lipolysis, and blood was collected from tail vein at indicated hours to measure TG levels [5].

qRT-PCR and western blotting

Methods for qRT-PCR and Western blotting have been described previously [5, 19], with oligo nucleotide primers and antibodies listed in Supporting Table 2 and Supporting Table 3, respectively.

RNAseq sample preparation and data analysis

Mice were subjected to a 16-week feeding with LFD, HFHF diet, or HFHF diet plus resveratrol (HFR). By the end of the experiment, mice liver tissues were collected for RNA isolation. Total RNA was harvested using RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) and further quantified and analyzed using Nanodrop spectrophotometer and Bioanalyzer. One microgram of total RNA was utilized and sent to Center of Applied Genomics (Sickkids Hospital, Canada) for sequencing library construction, as we have described previously [11]. Data processing and analyzing were conducted through a standardized pipeline called RNAseq IMmune Analysis Pipeline, per literature description [21]. Briefly, unprocessed FASTQ files containing raw data were downloaded and transferred. The RNAseq reads were aligned against the mm10 reference genome assembly (Genome Reference Consortium Mouse Build 38) obtained from the NCI Genome Data Commons (GDC) using STAR (version 2.4.2a). Quality control was performed on aligned BAM files using RSeQC and then expression levels were quantified using SALMON (V.0.14.0). After converting Ensemble IDs to mouse gene symbols (GRCm38.p6), the reads per gene were normalized and differentially expressed genes were analyzed with DESeq2 (V1.22.2). Raw data and processed data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (GSE241713).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Normality test was performed using Shapiro-Wilk test and for normally distributed data with similar variance, student’s unpaired one-tailed or two-tailed t test was performed. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post-hoc correction was applied for calculating the statistical significance. Statistical details are presented in the figure legends and n values means biological replicates in all experiments. In the current study, the sample size was based on previous studies that employed mice, no power analysis and blinding was performed. In all cases, p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Male but not female lFgf21

-/- mice on LFD feeding show impaired fat tolerance

We have generated lFgf21-/- mice and the littermate controls (Fgf21fl/fl) (C57BL/6J genetic background) for current study by mating Alb-Cre with Fgf21fl/fl, as illustrated in Fig. S1A. lFgf21-/- mouse liver showed barely detectable FGF21 (Fig. S1B–D), while FGF21 expression in both brown adipose tissue and hypothalamus were virtually unaffected (Fig. S1E, F).

Six-week-old male and female lFgf21-/- mice and the control Fgf21fl/fl mice were fed with LFD for 12 weeks, while three metabolic tolerance tests (GTT, ITT, and PTT) were conducted at indicated time for all mice (Fig. 1A). On LFD feeding, male and female lFgf21-/- mice exhibited comparable glucose, pyruvate, and insulin tolerance when compared with age and sex-matched control littermates Fgf21fl/fl mice (Fig. 1B–G). There were no appreciable differences on body weight with hepatic FGF21 knockout in both sexes (Fig. 1H, I).

The above mice were then fed with LFD for an additional 3-week period (Fig. 1A), followed by collecting random blood samples and conducting FTT. Mice were then fasted overnight before they were sacrificed for tissue sample collections. As shown, male lFgf21-/- mice exhibited elevated random and fasting plasma TG levels, along with a trend toward impaired fat tolerance (p = 0.0519 for the area under the curve of the FTT) when compared with corresponding littermate controls (Fig. 2A, B). Such defects were not observed in female lFgf21-/- mice (Fig. 2C, D). We then assessed the expression of a battery of hepatic genes that are related to the FGF21 cellular signaling. Expression levels of genes encoding FGFR1 (Fgfr1) showed a trend toward reduction; while those encoding KLB (Klb) and two FGF21 downstream mediators (Ehhadh, which encodes enoyl-CoA hydratase and 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase; and Ppargc1a, which encodes PPARG coactivator 1 alpha) were significantly attenuated in male lFgf21-/- mice (Fig. 2E). In female lFgf21-/- mice, only Ppargc1a level was reduced. Interestingly, unlike male lFgf21-/-, Klb expression was significantly elevated in female lFgf21-/- mice, potentially due to an unidentified sex-dependent compensatory mechanism (Fig. 2F). We also assessed expressions of liver Fgf1 and gut (ileum) Fgf15, asking whether hepatic FGF21 deficiency results in elevated Fgf1 or Fgf15 expression for compensation. No such compensatory elevation was observed in lFgf21-/- mice (Fig. 2G, H). Together, we conclude that male but not female lFgf21-/- mice showed impaired lipid homeostasis in the absence of obesogenic dietary challenge, associated with reduced hepatic expression of Fgfr1, Klb, and Ehhadh. Our following investigations were then performed on male mice only.

Curcumin intervention improves lipid homeostasis in control but not lFgf21

-/- mice with the obesogenic dietary challenge

We reported previously that in HFD-challenged male mice, curcumin or anthocyanin intervention regulated hepatic FGF21 production and improved FGF21 sensitivity in hepatocytes [6, 22]. Curcumin intervention stimulated hepatic FGF21 expression in mice on LFD feeding and attenuated HFD-induced hepatic FGF21 over-expression and FGF21 resistance [6]. Here we aim to determine whether hepatic FGF21 is required for curcumin in exerting its major metabolic beneficial effect, especially lipid homeostatic effect in mice on obesogenic dietary challenge. As shown, male lFgf21-/- mice or the control littermate Fgf21fl/fl mice were fed with HFHF diet without or with curcumin intervention for 15 weeks (Fig. 3A). In control littermates, curcumin intervention moderately attenuated HFHF diet-induced body weight gain (Fig. 3B, C), reduced fasting serum and hepatic TG contents (Fig. 3D-E), and improved lipid tolerance (Fig. 3F). Curcumin intervention also reduced hepatic expression of ChREBP, as well as expression of genes that encode ChREBP (Mlxipl) and fatty acid synthase (Fasn) (Fig. S2A, B). In lFgf21-/- mice, none of the above regulatory effects of dietary curcumin intervention were observable (Fig. 3G–K and Fig. S2C, D). We hence conclude that liver FGF21 is required for curcumin intervention in exerting its metabolic beneficial effect, especially the improvement of lipid homeostasis.

In obesogenic diet-challenged male mice, resveratrol intervention also regulates hepatic FGF21

In 2014, Li and colleagues reported that resveratrol treatment increased the transcriptional activity of FGF21 promoter [7]. We hence ask whether in vivo resveratrol intervention in wild type mice with an obesogenic dietary challenge affects hepatic FGF21 expression, FGF21 sensitivity, or FGF21 mediated cellular signaling events. Here we conducted such assessments in two different sets of mice. In the first set, wild type C57BL/6J mice were fed with LFD, HFD, or HFD with resveratrol intervention (HFD+Res) for 8 weeks (Fig. 4A). In such experimental settings, hepatic Fgf21 expression was reduced by HFD feeding, and the reduction was reversed by resveratrol intervention (Fig. 4B). Hepatic FGF21 protein expression was not significantly affected by HFD while concomitant resveratrol intervention exhibited a stimulatory effect on hepatic FGF21 expression (Fig. 4C). Importantly, resveratrol intervention increased the expression of Fgfr1, which was reduced by HFD challenge (Fig. 4D). Klb level was not significantly affected by 8-week HFD challenge, while resveratrol intervention exhibited a stimulatory effect on hepatic Klb expression (Fig. 4E). Among the four downstream effectors of FGF21 we have assessed, expression of Ehhadh was inhibited by HFD and the inhibition was effectively reversed by concomitant resveratrol intervention. Acox1 (encodes Acyl-CoA Oxidase 1) expression was not affected by HFD challenge while resveratrol intervention elevated its expression level. HFD challenge significantly reduced expression of Ppargc1a, while resveratrol intervention generated no appreciable reversing effect in the current experimental settings. Finally, hepatic Pdk4 (which encodes pyruvate dehydrogenase lipoamide kinase isozyme 4) level was not affected by HFD challenge or resveratrol intervention in our current experimental settings (Fig. 4F). The above observations suggest that like curcumin intervention reported previously by our team and by others [6, 23, 24], resveratrol intervention also targets hepatic FGF21 or its downstream signaling events.

Fructose consumption is known to up-regulated hepatic FGF21 expression, associated with the development of insulin resistance [25]. In the second set of mice, we challenged Fgf21fl/fl mice with HFHF diet without or with resveratrol intervention (HFR) for an extended period, as indicated in Fig. 5A. As shown, 16-week HFHF-diet challenge significantly increased hepatic Fgf21 levels, while resveratrol intervention attenuated the elevation effectively (Fig. 5B). At FGF21 protein level, elevation was observed in mice with HFHF challenge, without or with 16-week resveratrol intervention (Fig. 5C).

We then collected liver tissues from those mice for RNAseq analysis. As anticipated (Fig. 5D, Fig. S3, and Supporting Table 4), HFHF-diet challenge increased hepatic expression of Fgf21 but reduced the expression of Klb, while those effects were reciprocally reversed by 16-week dietary resveratrol intervention. The attenuation effect of HFHF-diet and reversible effect of resveratrol intervention was also observed on certain downstream effectors of FGF21 signaling, which were then further verified by qRT-PCR analyses (Fig. 5E–G). As shown in Fig. S3, HFHF diet feeding most significantly repressed expression of genes including Eif4ebp3 (which encodes eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 3) and Zbtb16 (which encodes zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 16), and those genes were also significantly restored by resveratrol intervention. Exact metabolic functions of these two genes remain to be further explored. Additional information on the effect of HFHF diet challenge and resveratrol intervention on hepatic gene expression are presented in Figs. S4 and S5.

Dietary resveratrol intervention improves glucose tolerance and reduces serum and hepatic TG levels in HFHF challenged control but not lFgf21

-/- mice

We then directly compared the effect of resveratrol intervention in Fgf21fl/fl mice and lFgf21-/- mice with HFHF diet challenge (Fig. 6A). As shown, glucose tolerance was improved by resveratrol intervention in the control littermate Fgf21fl/fl mice but not in lFgf21-/- mice (Fig. 6B). Dietary resveratrol intervention also attenuated HFHF diet-induced fasting hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in Fgf21fl/fl mice but not in lFgf21-/- mice (Fig. 6C, D). Interestingly, in both Fgf21fl/fl and lFgf21-/- mice, 16-week dietary resveratrol intervention attenuated HFHF-diet induced body weight gain (Fig. 6E, F) and fat accumulation (Fig. S6), although the degree of the attenuation in Fgf21fl/fl mice appeared much stronger than that in lFgf21-/- mice (Fig. 6E, F and Fig. S6A–C). In addition, in both Fgf21fl/fl and lFgf21-/- mice, we observed that resveratrol intervention reduced Fgf21 expression in epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT) (Fig. S6D, E). We have also examined plasma FGF21 level in Fgf21fl/fl mice. As shown, resveratrol intervention attenuated plasma FGF21 level (Fig. S6F). Nevertheless, in Fgf21fl/fl but not lFgf21-/- mice, resveratrol intervention attenuated HFHF diet-induced elevation on serum as well as hepatic TG levels (Fig. 6G, H). Thus, although hepatic FGF21 is required for resveratrol intervention in exerting its metabolic beneficial effect on improving energy homeostasis, the body weight lowering effect of dietary resveratrol intervention does not completely rely on hepatic FGF21. Whether this involves FGF21 expressed in adipose tissues or elsewhere deserves further investigations.

Discussion

Although native FGF21 and a few FGF21 analogues were shown to bring metabolic and other beneficial effects in various diseases models [8, 26, 27], individuals with obesity show elevated hepatic and plasma FGF21 levels, suggesting that obesity represents an FGF21 resistance state [8, 28, 29]. We and others have reported that dietary intervention with curcumin or anthocyanin, or other dietary polyphenols, regulate plasma and hepatic FGF21 levels, as well as FGF21 sensitivity [6, 17, 22, 23]. Other edible plant compounds, such betaine, were also shown to regulate hepatic FGF21 [30]. Importantly, in mice on LFD feeding, dietary curcumin or anthocyanin intervention stimulated hepatic FGF21 level; while in mice on HFD, the intervention attenuates HFD-induced FGF21 over-expression, associated with the reversal on HFD-induced repression on Fgfr1 or Klb expression [6, 22, 24]. These regulatory events are commonly interpreted as the improvement of FGF21 sensitivity [6, 31].

We show here that on LFD feeding, male but not female lFgf21-/- mice exhibited a moderate impairment on fat tolerance, associated with a trend of reduced expression of Fgfr1, and significant attenuation on expression of genes including Klb, Ehhadh, and Ppargc1a. Interestingly, female lFgf21-/- mice exhibited elevated Klb expression compared to the littermate controls; whereas such effect was absent in male mice; suggesting the existence of a sex-dependent adaptive response. Previously, we and others have also shown that female hormone estradiol (E2) increased FGF21 production [28, 32]. How can female hormones including E2 compensate the lack of hepatic FGF21 on lipid homeostasis in the absence of obesogenic dietary challenge remains to be further investigated. In the absence of an obesogenic dietary challenge, extra-hepatic FGF21, including those generated in adipose tissues, brain, and elsewhere, might be sufficient for female mice in maintaining metabolic homeostasis. Nevertheless, we presented here our comprehensive observations in HFD-challenged mice on hepatic FGF21 regulation with resveratrol intervention and then further expanded our investigation with HFHF diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance mouse model, show that resveratrol intervention reversed the repression of HFHF-diet on expression of Fgfr1 and Klb, as well as genes that encode FGF21 effectors. We further underpinned Fgf21 gene expression in extra-hepatic organs including BAT and eWAT and determined that resveratrol intervention repressed Fgf21 expression in both HFHF-challenged lFgf21-/- and its littermate controls. Adipose tissue FGF21 signaling has been determined to regulate browning in adaptive thermogenesis and our own investigation also showed that dietary curcumin intervention increased thermogenic capacity [15, 33, 34]. Whether resveratrol intervention-mediated FGF21 signaling also contribute to adaptive thermogenesis and whether FGF21 serves as an autocrine or paracrine to exert its effects require further investigation. Importantly, we demonstrated here that hepatic FGF21 is required for either curcumin or resveratrol intervention in exerting their metabolic beneficial effect in the obesogenic diet challenged mouse models, although the body weight lowering effect of resveratrol or curcumin intervention may only partially rely on hepatic FGF21. In a previous investigation, we also noticed that hepatic FGF21 is not absolutely required for the GLP-1RA liraglutide in lowering the body weight in mice with HFD challenge [11].

How can hepatic FGF21 mediate metabolic beneficial effect of both nutrient restriction [3, 35] and dietary polyphenol interventions [6, 22, 24]? Why hepatic FGF21 is required for both the GLP-1R agonists (including liraglutide, semaglutide and exenatide) and various dietary interventions [2]? The diabetes drug metformin, which is also a chemical isolated from plant, was shown to induce GLP-1 secretion, and such function contributes to the actions of metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes [36]. As metformin has been shown to exert its function via “reshaping” gut microbiome, it remains to be determined whether gut microbiome is involved in regulating gut GLP-1 production or secretion [37]. A recent study by Martin and colleagues showed that in the absence of gut microbiome, FGF21 adaptive pathway is desensitized in response to dietary protein restriction [38]. We are aware of the fundamental role of gut microbiome in health and diseases for decades, and a few recent studies have demonstrated that beneficial effects of resveratrol intervention are strongly associated with alterations in gut microbiome [39,40,41]. Targeting gut microbiome or intestinal signaling cascades, including the gut hormone GLP-1, the intestinal Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) or Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) medicated bile acid signaling cascades, are also shared with the diabetes drug metformin, other phytomedicine including red ginseng extracts, theabrownin isolated from Pu-erh tea, blueberry and cranberry anthocyanin extracts [37, 42,43,44,45]. Prior to reporting our current investigation, we have reported very recently that resveratrol intervention target gut microbiome, leading to the attenuation of gut bile acid/FXR signaling and chylomicron secretion, and improved lipid homeostasis [5]. It is plausible to suggest that gut microbiome mediates functions of the two categories of dietary interventions (Fig. 6I), with the participation of gut metabolites and gut produced hormones, including GLP-1 and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), as well as gut/brain axis, gut/liver axis, or other axis that links gut and other peripheral organs, as we have reviewed recently [2].

Hepatic FGF21 is required for curcumin or resveratrol in exerting their major metabolic beneficial effects. The existence of common targets, such as FGF21, for GLP-1RAs and various types of dietary interventions, makes us to recognize the link between these two categories of “medicines”, between these two lines of biomedical research, brings us a novel angle in understanding and further investigation of metabolic disease treatment and prevention, with prescribed drugs and various phytomedicine.

Responses