Horizontal metaproteomics and CAZymes analysis of lignocellulolytic microbial consortia selectively enriched from cow rumen and termite gut

Introduction

Lignocellulose (LC) is the major component of plant cell walls and the

primary source of renewable carbon on Earth available for a sustainable production

of biofuels and commodity chemicals. However, biomass bioconversion is very

challenging due to LC recalcitrance [1].

Therefore, to improve the economic feasibility of biomass biorefining, more

effective strategies are required to break down LC.

In natural ecosystems, LC decomposition is performed by complex

microbial communities producing large enzyme arsenals. These communities includes

the ones involved in the composting processes [2, 3], cellulose and

leaf-litter decomposition in soils [4,5,6], and the digestive systems of herbivores [7] and termites [8, 9]. In the case of

herbivores, LC decomposition is the result of the symbiosis between the animal host

and its digestive microbiome, the latter providing short-chain volatile fatty acids

(VFA) and microbial proteins to the host. Therefore, to improve the economic

feasibility of biomass biorefining, one strategy is to develop Nature-inspired

solutions by harnessing the power of naturally occurring LC-degrading microbiomes.

However, the challenge is to deploy such microbial ecosystems in controlled

bioreactor environments.

LC deconstruction is a complex process that marshals a large diversity

of enzymes rarely produced by a single microbial species [10]. The process involves carbohydrate-active

enzymes (CAZymes) that break down, modify or assemble glycans [11]. CAZymes are classified into 5 main

categories, namely glycoside hydrolases (GH), glycosyltransferases (GT),

carbohydrate esterases (CE), polysaccharide lyases (PL) and auxiliary activities

(AA), and their appended non-catalytic carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM)

[11]. Other non-catalytic protein

domains include cohesins (COH), dockerins (DOC) and S-layer homology (SLH) domains.

These are often appended to CAZymes and provide the means to incorporate cellulosome

complexes that link enzymes to the cell surfaces [12]. Microorganisms present in LC degrading environments such as

the digestive tract of termites or cow rumen provide vast reservoirs of CAZymes,

which are sources of new potent lignocellulolytic enzymes for biomass deconstruction

[13].

To better understand the biological mechanisms that underpin LC

degradation, meta-omics technologies are being used to investigate how microbial and

enzymatic synergies contribute to LC deconstruction [14]. 16 S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics

have provided information on both the taxonomic and metabolic potential of various

lignocellulolytic microbial communities [7, 10, 15]. Moreover, they have shed light on the

synergies between the members of these communities [2, 4, 16]. However, these approaches do not inform on

the actual metabolic activities of community members, nor do they provide details of

the effective role of genes in ecosystem functioning. For this, metaproteomics is a

precious tool since it provides information on the entire protein component of

microbial communities, links proteins to specific microbial taxa and correlates

their presence with metabolic activity [17]. This powerful approach thus provides useful information on

metabolic networks and symbiotic microbial interactions.

Previous metaproteomics studies on rumen ecosystems have shown that the

most abundant proteins are affiliated to Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota), Firmicutes

(Bacillota) and Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota) [18], where LC degradation is associated with high redundancy of

key enzyme activities. Regarding the termite gut microbiome, metaproteomics of

Nasutitermes corniger showed that among 197

identified proteins with known functions, 48 proteins are directly related to glycan

hydrolysis [19]. However, due to the

high complexity of these natural ecosystems and the limited number of proteins

detected, these metaproteomic studies neither revealed the specific roles of

individual microbial taxa, nor the temporal dynamics of proteins involved in LC

breakdown.

To gain insight into how lignocellulolytic ecosystems function,

selective ecosystem enrichment is often used to reduce microbial complexity and hone

community functions for use in bioprocesses [20,21,22,23].

However, most previous metaproteomic studies performed on simplified ecosystems only

revealed a small number of proteins [23,24,25,26,27]. They

also fail to fully capture the temporal dynamics of microbial species and CAZymes,

although one previous study has provided insight into the protein expression

dynamics of a subset of enzymes [28].

To further elucidate the mechanisms employed by microbial consortia to decompose LC,

it is thus vital to fully capture the temporal dynamics of all active species and

expressed proteins. Using LC as the sole carbon source, we postulate that

inoculum-specific microbial species can be maintained, although we expect that

time-dependent enzyme profiles to vary depending as a function of substrate

modifications occurring during the degradation process. Nevertheless, we also expect

all enzyme profiles will display genericity, regardless of the source of the

inoculum.

In previous studies, we reported the selective enrichment of two

anaerobic lignocellulolytic microbial consortia derived from cow rumen (RWS) and

from the termite gut microbiome of Nasutitermes

ephratae (TWS) [20,

21]. These naturally-occurring

anaerobic microbiomes present significant and contrasting levels of diversity, and

display great potential for LC degradation [7, 8, 13]. The enrichment of these microbiomes by a

sequential batch reactor process, using wheat straw as sole carbon source, resulted

in consortia displaying high LC-degradation activity and good ability to produce

carboxylates (mainly VFAs with acetate, butyrate and propionate as main products).

These products are valuable chemicals for producing bioplastics and liquid biofuels

[29, 30]. The kinetic characteristics of these enriched consortia were

determined by measuring LC-degradation rate, xylanase activity and carboxylate

production. Herein, we expand on previous work, performing shotgun metaproteomic

analysis over the reaction period of wheat straw hydrolysis by RWS and TWS

consortia.

Materials and methods

Lignocellulose degradation by RWS and TWS microbial consortia

The kinetic behaviors of the enriched lignocellulolytic microbial

consortia derived from cow rumen (RWS) and termite gut (TWS), summarized in

Table 1 and Figure S1, have been described previously

[20, 21]. For each consortium, two identical

anaerobic bioreactors were carried out, using a mineral medium containing wheat

straw as the sole carbon source (20 g.L−1).

Bioreactors were operated for 15 days at 35 °C under stirring (400 rpm) and pH

control (6.15), as detailed in Supplementary

Material and Methods.

The temporal dynamics of species and expressed proteins in RWS and

TWS along LC degradation were assessed by 16 S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun

metaproteomics performed on four time points for each bioreactor. Time point

selection was based on wheat straw degradation, VFA production and xylanase

activity profiles (Table 1). The first

point (T1) corresponds to an early phase where xylanase activity and

lignocellulose degradation are low. Time points 2 and 3 (T2 and T3) correspond

with the start and end of maximal xylanase activity and peak lignocellulose

degradation rate. The fourth time point (T4) captures the final phase, when

wheat straw degradation, VFA production and xylanase activity stagnate.

Microbial diversity analysis

Total DNA/RNA were extracted from the pellet fraction of 1.5 mL

samples (13,000 x g, 5 min, 4 °C) using the

PowerMicrobiome isolation kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. After DNA purification (AllPrep DNA/RNA MiniKit,

Qiagen), the hypervariable V3-V4 region of the 16 S rRNA gene was amplified by

Illumina MiSeq sequencing (GenoToul Genomics and Transcriptomics platform,

Toulouse, France) using the conditions and primers previously described

[31]. Sequencing data was

analyzed using Find Rapidly OTUs with Galaxy solution (FROGS) pipeline

[32], as detailed

in Supplementary Information. R

CRAN software (v4.0.0) was used for further analysis. Diversity metrics were

obtained using R’s Phyloseq package v1.32.0 [33]. Sequencing data were deposited to the Sequence Read

Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA729464.

Metaproteomics analysis

Protein extraction, peptides digestion and mass spectrometry

analysis

Protein extraction was carried out on 3 technical replicates

per sample (3 mL), using a phenol buffer following the procedure for complex

sediment samples [34] and

separated by SDS-PAGE. After trypsin proteolysis (Promega, Fitchburg, WI,

USA) and purification of peptides (ZipTips, C18, Merck, Millipore,

Billerica, MA, USA), the dried samples were stored at −20 °C.

Mass spectrometry (MS) was performed on a Q Exactive HF MS

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a TriVersa NanoMate

(Advion, Ltd., Harlow, UK) source in liquid chromatography chip coupling

mode. Peptide separation settings were as in procedures previously described

[35]. MS data have been

deposited into the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the proteomics identification (PRIDE) partner repository

[36]. Peptide

identification was performed with the Thermo Proteome Discoverer software

(v1.4; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using Sequest HT against

bacterial sequences only (plant and eukaryotic sequences excluded) of

Uniprot-TrEMBL database (release date of 6th

April 2016) [37]. Peptide

identification considered a false discovery rate (FDR) below 1% calculated

by Percolator [38], a minimum

length of six amino acids, and a peptide rank of one. Protein matches were

only accepted if they were identified by a minimum of one unique peptide and

a high confidence. “Protein Groups” (hereafter referred to as proteins) were

form with strict parsimony and using the highest scoring protein in the

group as the confident master candidate protein. The detailed protocol is

included in Supplementary Material and

Methods.

Protein abundance, taxonomic and functional annotations

PROPHANE pipeline (www.prophane.de) [39] was used

for protein identification and taxonomic annotation using, respectively, the

highest sequence similarity to the UniProtKB/TrEMBL database and BlastP

considering Bacteria proteins only. Fungal proteins were not included as no

anaerobic fungi were detected by qPCR in RWS (data not shown) and no fungi

are present in the gut of higher termites [40]. Functional predictions of cluster of orthologous

groups proteins (COGs) and Pfam (Protein families) domains were obtained

with, respectively, RPS-BLAST algorithm and the COG collection (release

22.03.2003) [41], considering

the first hit for each protein (e-value ≤ 0.01), and the Hidden Markov Model

profiles with HMMER3 algorithm, considering the first hit for each protein

(gathering cut-off) [42]. Only

identified proteins were retained for further analysis. For each sample,

PROPHANE estimated protein abundance based on the normalized spectral

abundance factor (NSAF) [43].

Replicate-to-replicate variation was assessed by Pearson correlation

analysis using the cor R function, accepting a minimum value of 0.7.

Proteins present in only one technical replicate were discarded; remaining

proteins were expressed as mean values. Computational assignment of protein

functions were carefully checked, completed, and manually curated.

CAZymes annotation

The identified proteins were assigned to CAZyme families

following the day-to-day updates procedure of the CAZy database (accessed

March 30, 2018) as described previously [44, 45].

Briefly, protein sequences were compared to the full-length sequence of

previously annotated proteins, stored internally in the CAZy database, using

BlastP (version 2.3.0 + ). All remaining sequences with no hit were compared

with BlastP to a library of individual modules (catalytic or ancillary) and

a HMMER3 search against a collection of hidden Markov models based on each

CAZy family [45]. Presence of

signal peptides in CAZymes was predicted by SignalP 6.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-6.0/).

Data analysis and visualization

Hierarchical clustering (Ward method with Euclidean distance)

was used to group the samples with dist

and hclust R functions. Plots were

constructed using ggplot2 package v3.3.2. Relative abundances of bacterial

OTUs or proteins were aggregated at a target taxonomic level for stacked bar

plot representation. Low abundance taxa (<1% Phylum and <2%

Genus level), were gathered as “Other”. A unique protein affiliated to

Chitinispirillum, was excluded from

the analysis.

Statistical significance of differences was determined using

Wilcoxon tests with Benjamini-Hochberg p-value correction for pairwise

comparisons [46]. For

multivariate analysis, centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation of variables

[47] was performed to take

into account the compositional properties of our data. A correction factor

equivalent to 70% of the lowest value of each variable was applied to

eliminate zero values observed in the dataset [48, 49]. Microbial species and CAZymes that best discriminate

consortia and incubation time were investigated by principal component

analysis (PCA) and identified by multivariate integrative partial least

squares discriminant analysis (MINT-PLS-DA) performed with factoextra v1.0.7

and mixOmics v6.12.2 packages [50, 51].

Discriminant factors were validated with permutational multivariate analysis

of variance (PERMANOVA), using R’s vegan package v2.5–6 to test the

statistical significant differences [52].

Results

Data overview

16 S rRNA gene sequencing of the lignocellulolytic consortia RWS

and TWS generated 800,329 high quality reads (Supp. data 1); rarefying of samples to 15,000 sequences

captured most of the microbial diversity (Fig. S2). Metaproteomic analysis yielded a total of 10,342

proteins (Supp. data 1), with high

similarity between technical replicates (Pearson correlation >0.7;

Table S1) and similar coverage,

with an average of 2,792 proteins per sample (Table S2). 33.7% of total proteins were identified in both RWS and

TWS consortia (proteins with same accession numbers), while 35.4% and 30.9% of

proteins were specific to RWS and TWS, respectively. Hierarchical clustering of

overall proteins of RWS and TWS revealed consortia-specific profiles

(Fig. S3), evolving as a function

of LC degradation.

Taxonomic and functional profiles of RWS and TWS throughout wheat straw

degradation

Taxonomy deduced from 16 S rRNA gene sequencing data showed that

TWS displayed a lower richness and Shannon diversity index. However, the Shannon

diversity estimated from metaproteomics data [53] were very close for both consortia (Table S2). Indeed, a similar taxonomic composition

for the two consortia was revealed by the taxonomic affiliation derived from

both approaches, with a dominance of Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota)(>

60%), Firmicutes (Bacillota) (about 20%) and Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota)

(about 10%) phyla (Fig. S4). A minor

fraction of both communities belonged to Spirochaetes, while Fibrobacteres

(Bacillota) was exclusively found in RWS.

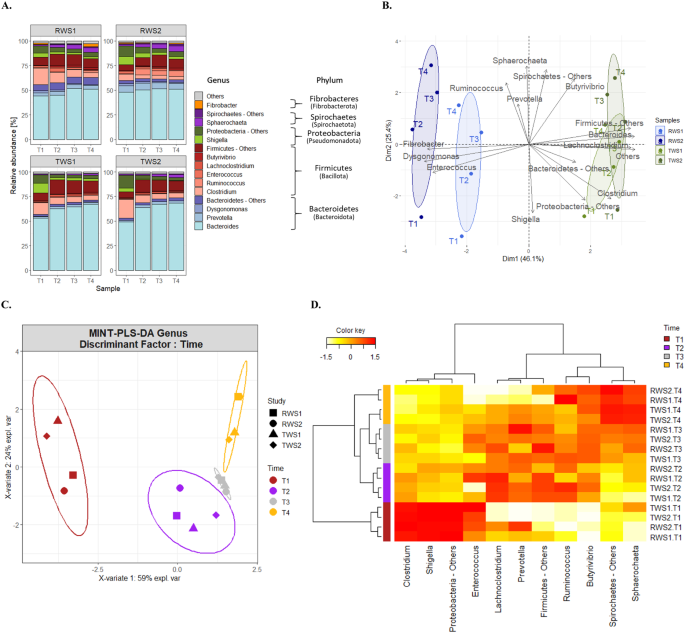

Affiliation of proteins at the genus level revealed that the active

populations, contributing most to protein production, belonged to Bacteroides in all samples of both consortia

(Fig. 1A), these remaining abundant

throughout the experiment. In second place was Clostridium, but its abundance decreased over time. Multivariate

PCA analysis of the abundance of all taxa-affiliated proteins, clearly

differentiated RWS and TWS communities (Fig. 1B). This difference was confirmed by a Wilcoxon test

(Fig. S5) showing a higher

abundance of proteins belonging to Dysgonomomas,

Fibrobacter and Enterococcus

in RWS while TWS showed a stronger abundance of proteins affiliated to Clostridium, Lachnoclostridium and Bacteroides, and to minor genera belonging to

Firmicutes-Others and Proteobacteria-Others. The temporal dynamics of the main

taxa of both consortia was evidenced by MINT-PLS-DA analysis, using the

incubation time as the discriminant factor. This revealed three clusters formed

by T1, T2/T3 and T4 samples (Fig. 1C).

T1 samples showed higher abundance of proteins affiliated to Clostridium, Shigella,

Enterococcus and Proteobacteria-Others (Fig. 1D) whose abundances decreased with incubation

time. Samples T2/T3 showed higher abundances of proteins affiliated to Lachnoclostridium, Prevotella and Firmicutes-Others while in samples T4, proteins

affiliated to Sphaerochaeta and Spirochaetes

showed higher abundance, which increased over the incubation period. Proteins

affiliated to Ruminococcus and Butyrivibrio were also abundant in T4 samples, but

also in T2 and T3 samples. PERMANOVA analysis (Table S3) confirmed that inoculum source (R-squared value 0.6214)

and incubation time (R-squared value 0.2022) were the key factors explaining the

protein-taxonomic composition and dynamics for both consortia.

dynamics.

A Taxonomic community

composition at genus level deduced from the identified proteins

(metaproteomics data) for RWS (top graphs) and TWS (bottom

graphs) (1 and 2 indicate the biological duplicates). Relative

abundance of proteins based on NSAFs (normalized spectral

abundance factors) was aggregated at the genus level for stacked

bar plot representation. The group “Others” gather phyla with

relative abundance less than 1% in the dataset. Within major

phyla, the group “Others” gathers genera with relative abundance

less than 2% in the dataset or unclassified genera. Proteins

belonging to the same bacterial phylum were represented with the

same color palette: Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota) (blue),

Firmicutes (Bacillota) (red); Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota)

(green), Spirochaetes (Spirochaetota) (purple),

Fibrobacteres (Fibrobacterota) (orange). B Impact of the inoculum origin evidenced by

Principal components analysis (PCA) ordination; PCA component 1

and 2 explained respectively 46% and 25.4% of the total variance

and C. Impact of the incubation

time in the community dynamic of RWS and TWS metaproteomes,

assessed by Multivariate Integrative Partial Least Square

Discriminant Analysis (MINT-PLS-DA) based on the abundance of

taxa deduced from proteins (genus level, CLR-transformed data).

MINT-PLS-DA component 1 and 2 explained 59% and 24% of the total

variance. Ellipses at 95% confidence. D Clustered Image Map (CIM) represented the most

discriminant genera of the different sampling times for RWS and

TWS. CIM was built using the genera contributing the most to the

two first MINT-PLS-DA dimensions. Hierarchical clustering was

derived using the Euclidean distance and Ward methodology.

Genera are represented in columns and samples in rows. The boxes

on the left highlights the clusters discriminating the sampling

points (yellow, gray, purple and dark-red). The abundance of

proteins affiliated to each genus is indicated by the

white-to-red color gradient (increasing values).

The status of lignocellulose-related functions of RWS and TWS,

revealed by COGs prediction from the protein dataset, revealed that the cellular

function “metabolism” was highly represented (about 45%) (Fig. S6A), with a strong representation of the

subrole “carbohydrate transport and metabolism” (about 15%), irrespective of the

sampling time and consortia. Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota) made the greatest

contribution to proteins involved in this function (Fig. S6B), while Firmicutes (Bacillota) and

Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota) provided a lesser contribution to this function.

Nevertheless, the normalization of proteins abundance at the phylum level,

revealed that the specific COG profile of Firmicutes (Bacillota) and

Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota) members was particularly focused on the

“carbohydrate transport and metabolism” function (Fig. S6C), whereas Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota)

species were involved in a wider range of functions.

Carbohydrate-active enzymes in RWS and TWS consortia

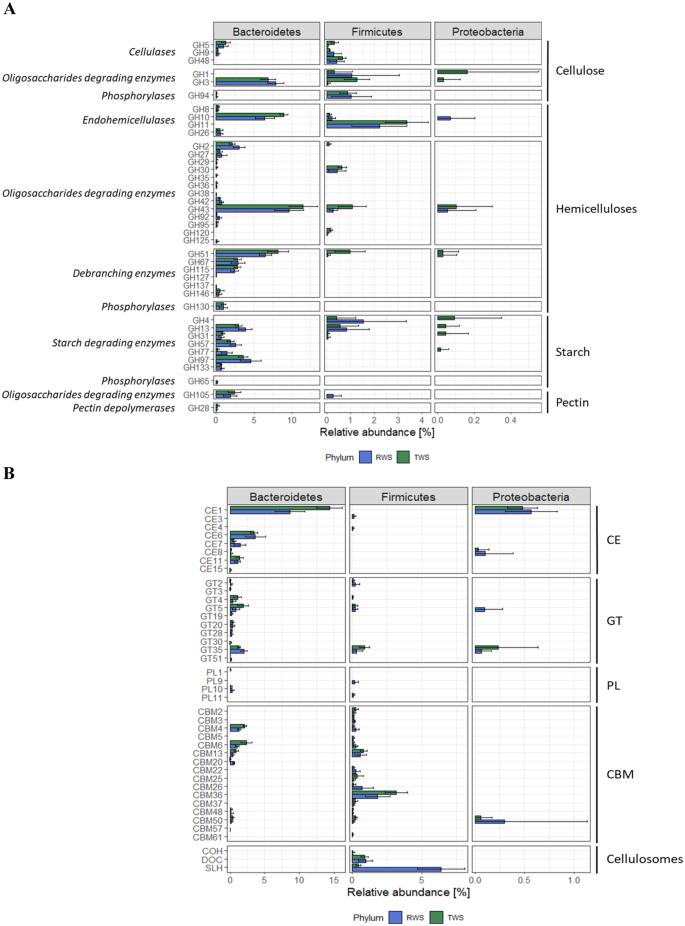

RWS and TWS expressed a large diversity of CAZymes involved in

plant cell wall degradation, with 423 proteins containing at least one CAZyme

domain (Supp. data 2). In silico prediction of signal peptides showed 222

CAZymes with a signal peptide (Supplementary data 1). 174 CAZymes (41%), distributed in 69 families, where

common to both consortia (Fig. S7A),

accounting for about 80% of the CAZymes abundance while 127 and 122 proteins and

15 and 10 CAZy families were exclusively found in RWS or TWS, respectively. Most

of these proteins contained GH domains, representing more than 70% of the CAZyme

domains detected, followed by CE domains (12–20%), CBMs

(9.5–12.5%), GT domains (5–8%) and PL domains (about 2%). These

CAZyme domains showed a higher average abundance in TWS than in RWS

(Fig. S7B). The main purveyor of

CAZymes in both consortia were Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota) members, producing

236 proteins corresponding to about 80% of the CAZyme abundance

(Fig. S7C) followed by Firmicutes

(Bacillota) (138 proteins, average 15%) while Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota)

expressed a minor fraction of them (24 proteins, <1.5%).

The most highly represented CAZymes are typically active on

hemicellulose and mainly affiliated to Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota)

(Fig. 2A), except those classified

GH11. These proteins are putative hemicellulases with endo-β−1,4-xylanase (GH8,

GH10, GH11) and β-mannanase (GH26) activities (Supplementary data 2). Hemicellulose-oligosaccharide-degrading

enzymes, with mainly β-xylosidase or α-L-arabinofuranosidase functions (GH43),

and hemicellulose-debranching enzymes with α-L-arabinofuranosidase (GH51) and

xylan α−1,2-glucuronidase (GH67, GH115) activities were also abundant.

Cellulose-degrading enzymes were mainly annotated as β-glucosidases (GH3) of

Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota) origin, while those with endoglucanase activity

mainly belonged to Firmicutes (Bacillota)(GH5, GH9, GH48) (Fig. 2A). Some of these proteins, were appended to

CBMs or cellulosome (COH and DOC) domains. Among the most prevalent proteins in

both consortia were Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota)- and Firmicutes (Bacillota)-

affiliated proteins related to starch degradation and including α-galactosidase,

1,4-α-glucan branching enzyme, α-glucosidase and α-amylase activities. According

to our data, Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota) were only minor CAZymes

contributors, being mostly sources of acetyl-xylan esterase activity (CE1;

Fig. 2B). Non-catalytic carbohydrate

binding modules (CBM), SLH, COH and DOC (i.e., cellulosome components) were mainly Firmicutes (Bacillota)

origin (Fig. 2B).

RWS and TWS.

A Relative abundance of

glycoside hydrolases (GH) in Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota),

Firmicutes (Bacillota) and Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota) phyla

of RWS and TWS metaproteomes. Abundances were normalized to

total CAZymes expression. Only GH targeting cellulose,

hemicelluloses, starch and pectin fractions are showed. Error

bars represent the standard deviation. B Relative abundance of carbohydrate esterases

(CE), glycosyl transferases (GT), polysaccharide lyases (PL),

carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM) and cellulosomes domains

(S-layer homology (SLH), dockerins (DOC), cohesins (COH))

present in Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota), Firmicutes (Bacillota)

and Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota) phyla in RWS and TWS

metaproteomes. Abundances were normalized to total CAZymes

expression. Error bars represent the standard

deviation.

CAZymes involved in lignocellulose degradation

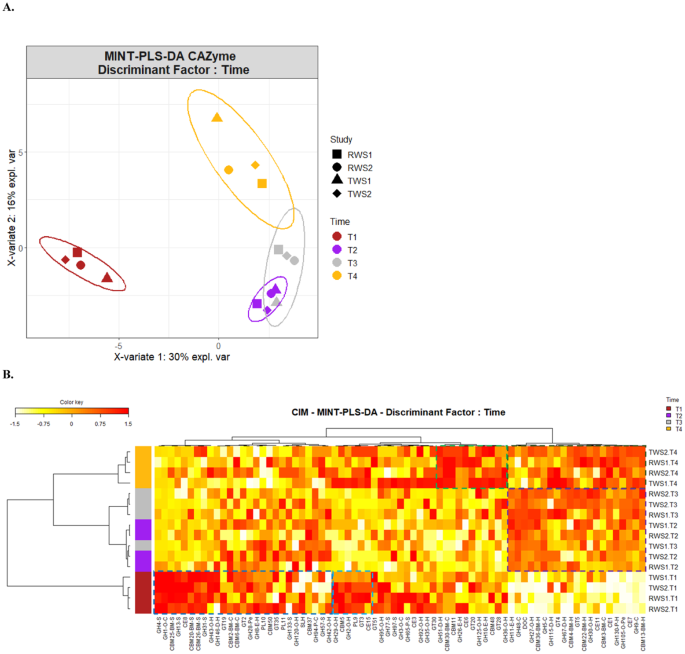

Multivariate statistical analyses were used to investigate how both

the inoculum origin and progression of LC degradation influenced the expressed

CAZyme profile. The PCA clearly separated RWS and TWS samples in function of the

inoculum (Fig. S8A, first component)

while the initial time points (T1) were clearly separated from the others

(Fig. S8B, second component).

PERMANOVA analysis (Table S4)

confirmed that the inoculum source and incubation time (R-square values of 0.253

and 0.284, respectively) were the key parameters determining the CAZyme

expression profiles. The importance of incubation time was confirmed by

Multigroup Supervised Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (MINT-PLS-DA),

using the incubation time as the discriminant factor. This analysis separated

the initial point (T1) from the subsequent sampling points (T2/T3) and from the

final point (T4) (Fig. 3A). T1 samples

(Fig. 3B, dark blue box) clustered

CAZymes with oligosaccharide-degrading activities linked to cellulose (GH1) and

hemicelluloses (GH43), pectin methylesterase (CE8), and α-glucan degradation

(GH4, GH13, GH31); they also included starch-specific CBMs (CBM20, CBM25,

CBM26). Other CAZymes with hemicellulose-oligosaccharide degradation (GH2 and

GH29) or polysaccharide lyase (PL9) activities, were also found in T1 samples

(Fig. 3B, light-blue box). However,

this enzyme cluster was also present (at a lower abundance) at the end of the

incubation period (T4). The cluster formed by the sampling points T2 and T3

(Fig. 3B, purple box), where most of

the LC degradation occurred, was characterized by high abundance of

endoglucanases (GH5, GH9 and GH48) and a large panel of hemicellulolytic

CAZymes, including endo-hemicellulases (GH11), deacetylating (CE1, CE11) and

debranching (GH67, GH115) enzymes and enzymes active on

hemicellulose-oligosaccharides (GH30, GH27). CAZymes related to

pectin-oligosaccharide degradation (GH105) were also found, as well as xylan- or

amorphous cellulose-specific CBMs (CBM3, CBM4, CBM13, CBM22, CBM36), dockerins

typical of cellulosome structures, and glucosyl/galactosyltransferases (GT4,

GT5). This cluster of CAZymes was also highly abundant at the latter stage of LC

degradation (T4; Fig. 3B, dark-green

box) along with a range of enzymes including endo-hemicellulases (GH10) and

xylan deacetylating (CE6) or hemicellulose-oligosaccharides degrading enzymes

(GH36, GH125) (Fig.3B, light-green box).

CBMs specific for cellulose (CBM30), hemicellulose (CBM11) and starch (CBM48),

and starch phosphorylases (GT20, GT28) completing this cluster. Similar results

were observed when the analysis was performed for CAZymes with predicted signal

peptide only (Fig. S9).

metaproteomes.

A Impact of the

incubation time in the CAZyme dynamics of RWS and TWS

metaproteomes, assessed by Multivariate Integrative Partial

Least Square Discriminant Analysis (MINT-PLS-DA) based on CAZyme

abundances (family level, CLR-transformed data). MINT-PLS-DA

component 1 and 2 explained 30% and 16% of the total variance.

Ellipses at 95% confidence. B

Clustered Image Map (CIM) represented the most discriminant

CAZyme families of the different sampling times in RWS and TWS.

CIM was built using the main CAZyme families explaining the

first two MINT-PLS-DA dimensions. Hierarchical clustering

(Euclidean distance and Ward method) represents CAZymes in

columns and samples (T1–T4) in rows. The boxes on the

left highlights the clusters discriminating the sampling points

(yellow, gray, purple and dark-red). The abundance of CAZy

families is indicated by the white-to-red color gradient

(increasing values).

Enzymes related to volatile fatty acid production in RWS and TWS

consortia

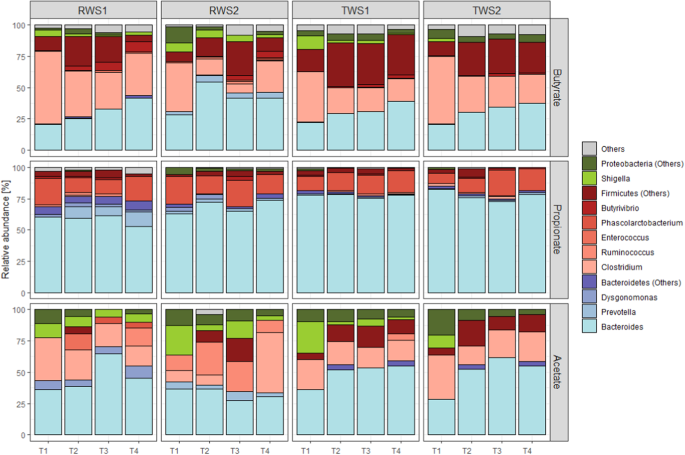

Lignocellulose degradation by RWS and TWS, like in other microbial

consortia, is associated with VFA production [40, 54]. RWS and

TWS produced mainly acetate, propionate and butyrate with a higher proportion of

the latter in TWS (Table 1; average

molar ratio of acetate:propionate:butyrate of 59:23:18 for RWS and 47:20:33 for

TWS). Based on previous COG assignments [16, 55,

56], metaproteomic data

revealed that the key enzymes involved in VFA biosynthesis constituted

2.8 ± 0.4% and 3.5 ± 0.2% of total protein abundance in RWS and TWS,

respectively. According to the higher butyrate production measured in TWS,

proteins related to butyrate biosynthesis (219 proteins) were more abundant in

this consortium (Figure S8). In both

consortia, this function was associated with a large variety of enzymes (numbers

of proteins indicated in parenthesis): acetyl/propionyl CoA carboxylase (3),

butyrate kinase (7), 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (26), enoyl-CoA hydratase

(17), acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (52), alcohol dehydrogenases YqhD (8) and

class IV (67), short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase (38) and Zn-dependent alcohol

dehydrogenase (1). Most of them were affiliated to Firmicutes (Bacillota) (138

proteins) and Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota) (23 proteins), but with abundance

levels similar for both phyla (Fig. 4).

At the initial phase of incubation (T1), Clostridium species were the major contributors of butyrate

biosynthesis enzymes in both consortia (67 proteins, about 30% abundance), but

subsequently the abundance of proteins affiliated to Bacteroides (16 proteins) increased, with higher levels of

expression being reached in the latter phase of biomass bioconversion.

VFAs production.

Relative abundance and phylogenetic origin of bacterial

enzymes involved in butyrate, propionate and acetate production

in the metaproteomes of RWS and TWS (1 and 2 indicate the

biological duplicates). Taxonomic affiliation of proteins at the

genus level. Proteins belonging to the same bacterial phylum

were represented with the same color palette: Bacteroidetes

(Bacteroidota) (blue), Firmicutes (Bacillota)(red) and

Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota) (green). For butyrate

biosynthesis: COG4770 (acetyl/propionyl-CoA carboxylase),

COG3426 (butyrate kinase), COG1250 (3-hydroxyacyl-CoA

dehydrogenase), COG1024 (enoyl-CoA hydratase), COG0183

(acetyl/butyryl-CoA acetyltransferase), COG1979 (alcohol

dehydrogenase YqhD), COG1454 (alcohol dehydrogenase, class IV),

COG1028 (short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase), COG1064

(Zn-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase). For propionate

biosynthesis: COG4799/0777 (acetyl/propionyl-CoA carboxylase),

COG2185/COG1884 (methylmalonyl-CoA mutase), COG0346

(methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase). For acetate production: COG1012

(NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase), COG0282 (acetate

kinase).

Propionate production was similar in both consortia

(Table 1) and appeared to be

associated with the presence of 66 propionate biosynthesis-related proteins with

three main functions: acetyl/propionyl-CoA carboxylase (34 proteins),

methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (23 proteins) and epimerase (9 proteins), revealing

that propionate was formed via the succinate pathway in both consortia. These

proteins were mainly affiliated to Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota), particularly to

Bacteroides (37 from 66 proteins)

(Fig. 4), while in Firmicutes

(Bacillota), Phascolarctobacterium was the

main contributor to this activity, providing about 20% of the relevant

enzymes.

Surprisingly, for both consortia and irrespective of the sampling

time, proteins involved in acetate biosynthesis were the least abundant among

the VFA-biosynthesis enzymes (61 proteins accounting for about 0.3% of the total

protein abundance; Fig. S10). The

presence of acetate kinases (26 proteins), phosphate acetyltransferases (22

proteins), and aldehyde dehydrogenases (13 proteins), expressed by all phyla

(Fig. 4), suggests that acetate

production in the consortia occurrs via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway. Seven of

these proteins affiliated to Bacteroides

formed the most abundant group, representing 39.3% and 49.3% of enzymes involved

in acetate biosynthesis in RWS and TWS metaproteomes, respectively, while those

belonging to Clostridium accounted for about

20% (Fig. 4). A low abundance of

proteins involved in carboxylate biosynthesis and belonging to Proteobacteria

(Pseudomonadota) was also detected, in particular for acetate and butyrate

production, at early stages of incubation.

Discussion

To gain new knowledge pertaining to LC-degradation process mediated by

microbial consortia, we studied two lignocellulolytic consortia, RWS and TWS,

derived from the complex microbiomes of the cow rumen and termite gut, respectively.

Compared to previous investigations, metaproteomic analysis of these consortia

enabled the detection of a high number of non-redundant proteins (10,342)

[23, 25, 28, 57], providing a complete repertoire of enzymes

involved in LC degradation and VFA production.

Although RWS and TWS are derived from contrasting parental microbiomes,

the taxonomic community composition deduced from 16 S rRNA gene sequencing and

metaproteomic data showed that the active communities of both consortia were rather

similar. They displayed a prevalence of Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota)- and Firmicutes

(Bacillota)-affiliated proteins, with the genera Bacteroides and Clostridium being

the main representatives of these phyla, respectively. This similarity is probably

the result of the selective pressure exerted by the wheat straw substrate during the

enrichment process, as reported in previous studies [58,59,60].

Bacteroides and Clostridium are key players in LC degradation in the digestive

microbiomes of herbivores, where they break down complex carbohydrates particularly

cellulose, xylan and starch [61,

62]. 16 S rRNA and metaproteomic

data confirmed that the most abundant genera were also the major source of plant

cell wall degrading enzymes in RWS and TWS consortia, in agreement with previous

observations [18]. This nevertheless

contrasts with previous metatranscriptomics studies on the termite gut [63] and studies performed on enriched microbial

consortium able to degrade rice and wheat straw [27], sugar cane bagasse [23] and a corn-stover degrading consortium [28]. Our findings reveal that the relationship

between the abundance of microbial phyla and their functional impact on the

community activity is not a simple one, and highlights the importance of

metaproteomics to assign functional roles to different phyla.

The metabolic functions of RWS and TWS, assessed by COG analysis,

revealed that proteins related to “translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis”,

“carbohydrate transport and metabolism” and “energy production and conversion” were

dominant in both communities, as reported in previous studies [16, 28, 57]. These COG

functions were expressed by the three main phyla found in RWS and TWS, Bacteroidetes

(Bacteroidota), Firmicutes (Bacillota) and Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota), but

phylum-normalized data showed that protein expression by the two latter was strongly

directed towards carbohydrate metabolisms, while the former (the major phylum

Bacteroidetes – Bacteroidota) was associated with larger spectrum of

functions.

A large diversity of CAZymes related to LC degradation, including

cellulases, hemicellulases and CBMs were detected in RWS and TWS metaproteomes. They

belong to 94 families, illustrating the relative richness of these consortia when

compared to the whole CAZy database (n = 472).

CAZymes in RWS and TWS accounted for about 4% of total proteins expressed. Although

most previous studies report the number of non-redundant CAZymes, rather than their

abundance [16, 18, 28], the abundance reported here is comparable to that measured

(3.5% and 5.9%) for other lignocellulolytic consortia [27]. This implies that dedicating less than 5%

of their expressed proteins to LC degradation, RWS and TWS achieved high

(>45% in our study) biomass degradation levels.

Taxonomic affiliation of CAZymes revealed that LC degradation by RWS

and TWS results from the combined action of proteins affiliated to Bacteroidetes

(Bacteroidota), the main purveyors of CAZymes, followed by Firmicutes (Bacillota). A

closer inspection revealed that the Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota) members mainly

produce hemicellulose-debranching and oligosaccharide-degrading enzymes as well as

enzymes involved in starch degradation. In contrast, Firmicutes (Bacillota) members

produced enzymes specific for β-glucan and β-xylan (cellulases and hemicellulases).

This differential expression of CAZymes offers interesting prospects for engineering

synergy. Moreover, it earmarks these two phyla as the key players in wheat straw

degradation. It is noteworthy that other studies do not systematically identify

these phyla as the dominant purveyors of CAZymes, particularly when considering the

termite gut microbiome [64]. To

rationalize this observation, we suggest that our results are the consequence of the

combined contributions of the original microbial consortium and the specific process

conditions employed [23, 26,27,28]. The

substrate, the enrichment process and the availability of oxygen all determine the

relative development of obligate aerobes, facultative aerobes and strict

anaerobes.

Although RWS and TWS consortia displayed taxonomic similarities, only a

third of proteins were common to both consortia. Multivariate analysis highlighted

the taxa and proteins linked to the parental inoculum source. Indeed, some features

can be attributed to the initial cow rumen and termite gut microbiome. For example,

the larger diversity of CAZymes and the ruminococcal and clostridial cellulosome

components characteristic of RWS are also characteristic of the cow microbiome

[65, 66]. Similarly, the high abundance of GH10, GH43, CE1 and

especially GH11, typical of TWS, is also a feature of termite gut microbiome

[67, 68].

Despite differences between RWS and TWS, multi-group MINT-PLS-DA

supervised analysis highlighted in both consortia Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota)- and

Firmicutes (Bacillota)-affiliated enzymes, particularly ones produced by Bacteroides, Clostridium and Enterococcus genera, were marshalled. According to annotation, these

enzymes target the minor starch fraction and holocellulose-derived oligosaccharides,

meaning that the aforementioned genera forage ready available resources and in doing

so facilitate further breakdown of holocellulose polymers. Similarly, in both

consortia the occurrence of Lachnoclostridium,

Prevotella and Other-Firmicute members was

associated with the principal LC biomass degradation phase, which was also related

with an increase in the abundance of CAZy families related to cellulose hydrolysis,

deacetylation and cleavage of hemicelluloses and pectin depolymerization. In

addition, during the last incubation stage, several CAZymes hydrolyzing and

deconstructing hemicellulose and hemicellulose-oligosaccharides also increased, as

well as various CBMs binding cellulose, hemicellulose and starch. Therefore, further

biochemical characterization of these enzymes could be of interest to elucidate

their specific role in LC-biomass degradation, in particular to identify enzymes

able to degrade the most recalcitrant components.

Concerning VFA biosynthesis, our data showed that acetate biosynthesis

was the result of Wood-Ljungdahl pathway in both our consortia, and highlighted the

major role of acetogenic bacteria belonging to Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota) and

Firmicutes (Bacillota) phyla. Propionate production in RWS and TWS mostly resulted

from the succinate pathway as evidenced by the detection of methylmalonyl CoA

mutases and epimerases [69], with

Bacteroides and Phascolarctobacterium species as the key propionate producers. This

is consistent with previous data that showed that the succinate pathway is the main

route reported for rumen [70]. Butyrate

biosynthesis resulted either from the conversion of butyryl-CoA into butyrate, using

butyrate kinase (synthesizes butyryl-phosphate) and phosphotransbutyrylase, or the

transfer of coenzyme A (catalyzed by butyryl-CoA:acetate-CoA transferase) between

acetate and butyrate. Although both routes are exploited by Firmicutes (Bacillota)

species, the second one was strongly enhanced in both consortia. This observation is

consistent with previous studies on the cow rumen and human gut microbiota that

revealed that Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota) are responsible for the majority of

acetate and propionate production, while butyrate biosynthesis is mainly handled by

Firmicutes (Bacillota) species [16,

71]. LC-hydrolysis remains the

limiting step and thus VFA-biosynthesis cannot be used to improve LC conversion into

VFA, but could be of interest to drive VFA production towards specific products

(e.g. butyrate).

A remarkable finding in this work is that no lignin-specific enzymes

(CAZyme AA class) were found, suggesting that ligninolysis did not occur under the

anaerobic culture conditions used. This concurs with previous lignin measurements

performed on RWS and TWS [20,

21]. Nevertheless, the fact that no

lignin-degrading enzymes were evidenced does not imply that these were absent,

because shotgun metaproteomics procures an incomplete image of expressed proteins.

Ultimately, to assert that no lignin degradation had occurred in our experiments, it

would be necessary to perform a thorough physicochemical and structural analysis of

the substrate before and after microbial treatment.

The CAZy classification database has been growing at a fast rate in

recent years, with new sequences being added daily and new families being regularly

defined. A comparison of the collection of GHs detected in our study with those

detected in previous omics studies (metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics,

metagenomics) performed on bovine rumen and termite-gut microbiomes

(Table S5 [65, 72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79])

revealed that this study unmasked greater diversity of cell wall degrading CAZymes.

Moreover, the comparison revealed that our study captured most CAZy families

degrading the plant cell wall, whereas the previous studies were less successful in

this regard. To a large extent, the greater coverage of GH families in our study can

be correlated with the growth of the CAZy database and its date of access

[11] and ongoing improvements to

the experimental techniques and bioinformatics pipelines used. However, we believe

it is also attributable to the fact that RWS and TWS are enriched consortia whose

functions are highly adapted for the degradation of raw lignocellulosic biomass.

Undoubtedly, future studies benefitting from further progress in metaproteomics and

the further expansion of the CAZy database will surpass our study. Hopefully, these

will provide an even deeper understanding of lignocellulolytic functions in

microbial ecosystems and provide the means to identify proteins that are currently

unclassified. Furthermore, our data showed that RWS and TWS consortia represent

excellent simplified models to study the mechanisms governing the complex

lignocellulose degradation process and to better understand and exploit multispecies

lignocellulolytic enzyme systems for biotechnological applications.

Responses