How central banks address climate and transition risks

The policy problem

Decarbonization and climate change entail risks for the global economy. Fossil fuel investments face stranded asset risks, that is, lost profits due to early retirement, as the global economy decarbonizes. Stranded asset risks threaten financial stability. Similarly, exposure to climate hazards contributes to financial instability. Clean energy investments, meanwhile, come with technology and market risks that—left unmitigated—result in lower climate mitigation. Over the last decade, central banks have taken on a role in examining and managing transition and physical climate risks. Yet the response from central banks has not been uniform: some have adopted measures of varying type and stringency; others have not taken any actions.

The findings

We find limited evidence that economic risks related to climate and energy are associated with central bank behaviour. While physical risks are associated with central bank actions to some extent, stranded asset risks and clean energy investment risks are not. Instead, central bank actions to manage risks are significantly and positively associated with domestic climate politics, including climate policy stringency and public concern with climate change. Our results thus suggest a risk mitigation gap between the magnitude of transition risks and central bank actions, and that central banks may not be entirely autonomous risk managers but responsive to political demands, reinforcing, instead of correcting for, lagging decarbonization policy. Our analysis is exploratory. Future research needs to move beyond cross-sectional to time series analysis, investigate the underlying mechanisms, and study the broader regulatory system for climate risk, including financial supervisors and private sector institutions.

The study

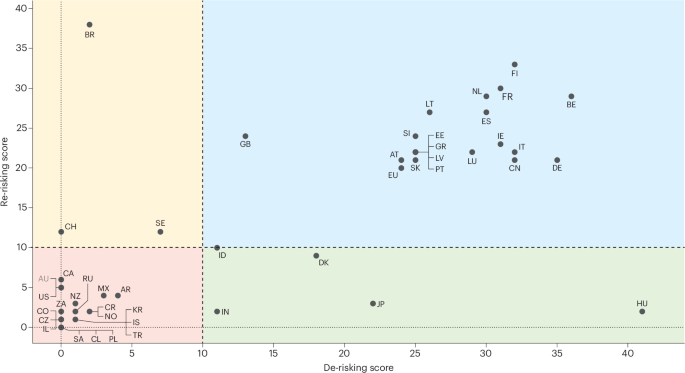

We provide a comprehensive, systematic study of central bank management of climate risks. We introduce an original dataset on climate risk management actions by central banks across 47 OECD and G20 countries and develop a classification system to identify actions that re-risk brown investments and de-risk green investments (Fig. 1). Re-risking refers to embedding transition risks and physical climate risks into financial risk management practices to ensure financial stability, whereas de-risking means reducing the risk of clean energy investments, that is, the technology, market, and policy risks of new clean energy technologies, to facilitate decarbonization. We use a simple linear regression model to test whether re-risking and de-risking scores are associated with economic risk factors (the size of the oil and gas sector and the financial sector as well as exposure to climate hazards) or political factors (climate policy stringency and public concern with climate change).

This graph plots each country’s calculated re-risking and de-risking scores. Re-risking refers to central bank actions that manage stranded asset risks and physical climate risks, while de-risking refers to actions targeting clean energy investment risks. Scores higher than 10 indicate that the country engages in substantial activity in that policy group, while scores 10 or lower indicate marginal efforts. The two-digit ISO country codes indicate country names. There is substantial variation in the extent to which countries re-risk and de-risk. The blue quadrant shows countries with high re-risking and de-risking scores. These are mostly member states of the European Central Bank, the UK, and China. The red quadrant includes countries with relatively less activity in both re-risking and de-risking scores, such as the United States, South Korea, Costa Rica, South Africa, and Russia. Countries in the yellow quadrant engage in more re-risking than de-risking (Brazil, Switzerland, Sweden). Last, countries in the green quadrant engage primarily in de-risking (Hungary, Denmark, Japan, India, Indonesia). Figure adapted from Shears, E. et al. Nat. Energy https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-025-01724-w (2025); Springer Nature Ltd.

Responses