Humic acid-dependent respiratory growth of Methanosarcina acetivorans involves pyrroloquinoline quinone

Introduction

Humic substances, also called humus, constitute the highly transformed fraction of natural organic matter that is derived from the residues of dead organisms and their degradation products [1]. Humus is present across terrestrial and aquatic environments including soil, wetlands and marine environments, representing a significant carbon pool over a range of biospheres [1]. Humus has long considered to be inert to biodegradation because of heterogeneous structures and amorphous compositions [2]. However, humus displays versatile reactivities with a diverse suite of organic compounds and minerals through both biotic and abiotic processes. Specifically, microbial respiration by humus reduction is a ubiquitous process that significantly impacts organic matter decomposition and the biogeochemical cycling of key elements in natural environments [1, 3].

The study of microbial humus respiration began two decades ago, when Lovley and coworkers showed that electrobacteria, such as Geobacter metallireducens and Shewanella alga from soil and freshwater anoxic sediments reduced humus, conserving energy to support their growth [4]. Subsequently, they found that reduced humus could also serve as an electron shuttle for humus-reducing microorganisms to reduce other insoluble electron acceptors [5]. The quinone groups in humus are the primary electron-accepting moieties, as evidenced by the accumulation of semiquinones as the main radicals during this metabolism [6]. Outer-membrane multiheme c-type cytochromes (MHCs) of humus-reducing microorganisms have been reported to be involved in extracellular electron transfer [7]. The anaerobic redox cycling of humus in sedimentary environments can facilitate the abiotic reduction of less accessible electron acceptors, such as insoluble Fe or Mn oxides, which thereby influences their biogeochemical transformation and speciation [8]. In addition, the redox cycling of humus can enhance the organic matter oxidation rates in diverse biospheres and may potentially play a regulatory role in the emission of greenhouse gases such as CO2 and methane, making it ecologically important for climate change [9, 10].

Although humus is reduced by anaerobic microorganisms with diverse physiologies from the domain Bacteria, relatively little is known of the role humus plays in the physiology of anaerobes from the domain Archaea. Methane producing anaerobes (methanogens), belonging to the domain Archaea, may also conserve energy for growth by anaerobic respiration with humus. Since the discovery of methanogens, it has been assumed that energy conservation for growth is by a fermentative mechanism in which electrons derived from the oxidation of substrates are transferred to an endogenous electron acceptor, methyl-coenzyme M, reducing the methyl group to methane accompanied by the generation of proton and sodium gradients driving ATP synthesis [11]. However, recent investigations showed that the methanogen Methanosarcina acetivorans is capable of respiratory energy conservation and growth by reducing Fe3+ and humus analog anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) [12,13,14]. Unexpectedly, Fe3+-dependent respiration accompanied methanogenesis revealing simultaneous respiratory and fermentative mechanisms of energy conservation [12, 13]. Membrane-bound Rhodobacter nitrogen fixation (Rnf) and F420H2 dehydrogenase (Fpo) complexes are energy-conserving sites, creating the proton and sodium gradients, respectively, via mediating membrane-bound electron transport [15, 16]. Methanophenazine (MP), which is a membrane-bound electron carrier analogous to ubiquinone further contributes to the proton gradient by mediating the transfer of electrons to intracellular CoMS-SCoB via a membrane-bound heterodisulfide reductase (HdrDE) [16, 17]. A gene encoding a membrane multiheme c-type cytochrome (MmcA) that is a subunit of Rnf complex was shown to be necessary for the extracellular AQDS reduction [14]. Based on this, MmcA was predicted to mediate the extracellular Fe3+ respiration [12, 13].

Herein we report that a major fraction of humus, humic acid (HA) reduction enhanced the growth of M. acetivorans above that attributed to methanogenesis when utilizing the energy sources methanol or acetate, results documenting both respiratory and fermentative modes of energy conservation. The MmcA-deleted M. acetivorans was still capable of performing both modes of energy conservation, suggesting an alternative extracellular electron transfer pathway for HA reduction. Evidences were presented that suggest a role for pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ)-binding proteins in electron transport to HA. Finally, bioinformatics analyses demonstrated that homologs of the PQQ-binding proteins are widely distributed in methanogens, with the highest abundance observed in the genus Methanosarcina. The work provides novel insight into interactions between humus and methanogens inhabiting diverse anoxic environments.

Results

HA-dependent respiratory growth of M. acetivorans is independent of MmcA

Although M. acetivorans has been shown capable of respiratory growth with humus analog AQDS when methanogenesis from methanol is inhibited [14], unknown is respiratory growth with environmentally relevant HA and its effect on methanogenesis. Also unknown are the roles for HA in respiratory growth and methanogenesis with acetate, the primary methanogenic substrate in nature. Figure 1A, C shows that methanogenesis, gaged by monitoring methane production and carbon source utilization, was enhanced during the mid-log phase in HA-amended cultures compared to HA-null cultures with either methanol or acetate as a carbon source. Figure 1B, D shows that growth, gaged by monitoring protein, was enhanced at three sampling points from mid-log phase to stationary phase in HA-amended cultures compared to HA-null cultures with either methanol or acetate as the growth substrate. Prominent and abundant coccoid-shaped M. acetivorans cells that attached to HA were detected by scanning electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. S1). Analysis of the electrochemical properties of the added HA indicated an increase in electron donating capacity and a decrease in electron accepting capacity at the end of growth compared to the beginning, showing that HA was reduced during growth (Supplementary Fig. S2). These results show that both HA-dependent respiratory and methanogenesis-dependent fermentative energy conservation supported growth. Respiratory energy conservation was further supported by a 2- and 3-fold enhancement of ATP levels from mid-log phase to stationary phase in HA-amended cultures compared to HA-null cultures with either methanol or acetate as the growth substrate which reflected an enhanced energetic state dependent on electron transport (Fig. 1B, D).

Time-dependent methane production and carbon source utilization of methanol-grown M. acetivorans (A), acetate-grown M. acetivorans (C), and methanol-grown ∆hpt&∆hpt∆mmcA strains (E). Time-dependent accumulation of cellular protein and ATP of methanol-grown M. acetivorans (B), acetate-grown M. acetivorans (D), and methanol-grown ∆hpt&∆hpt∆mmcA strains (F).

HA-augmented growth was the same for an identically cultured mutant deleted for the gene encoding MmcA constructed from a parental strain deleted for the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase gene (∆hpt), results indicating MmcA is not essential for electron transfer to HA (Fig. 1E, F). The addition of HA to the culture of another Methanosarcina sp., M. barkeri that does not possess any homolog of MmcA, reproduced the phenotype observed for M. acetivorans (Supplementary Fig. S3). The combined results show that HA-dependent respiratory growth of the two Methanosarcina spp, is independent of MmcA.

Identification of cell surface PQQ-binding proteins upregulated in HA-respiring cells

To gain insights into how HA respiration stimulates methanogenesis and growth, we performed transcriptomic analyses of HA-respiring cells and nonrespiring cells. The differentially expressed genes were screened with univariate statistical significance (log2 (FC) > 1.0 or <1.0, and p < 0.05). Among the 4462 genes in M. acetivorans, a total of 79 and 340 genes were upregulated in HA-respiring cells compared to nonrespiring cells grown with methanol and acetate, respectively. Totals of 60 and 16 genes were downregulated in HA-respiring cells compared to nonrespiring cells grown with methanol and acetate, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, none of the genes involved in the methanogenesis and energy conservation, such as the genes encoding Fpo and Rnf complexes, were significantly regulated in HA-respiring cells (Supplementary Table S1).

A gene cluster (MA4284 to MA4315) was significantly upregulated in HA-respiring cells grown with both methanol and acetate (Fig. 2C). The gene cluster contains a total of 32 genes, 19 of which were obtained for RNA sequence reads. The remaining 13 genes were not obtained for transcript reads, consistent with the information of these genes in the NCBI database, i.e., these are pseudogenes missing a functional N- or C-terminus (Fig. 2A). A total of 17 expressed genes have conserved N-terminal signal peptide sequences, and the predicted encoding products of these genes in the NCBI database are cell surface proteins. Detailed domain architectures of the 19 expressed products are shown in Fig. 2B, and a brief overview is provided in Supplementary Table S2. A total of 11 expressed genes (e.g., MA4284, MA4290-91, MA4294, MA4297, MA4305, MA4309-10, MA4312, and MA4314-15) are annotated as PQQ-binding β-propeller repeat proteins, which are composed of multiple β-propeller repeats with corresponding numbers of PQQ as cofactors and thus are also called quinoproteins [18]. Three others (e.g., MA4285, MA4289, and MA4292) are annotated as leucine-rich repeat (LRR) proteins, which have multiple LRR domains that are frequently involved in the formation of protein–protein interactions at the cell surface [19]. Most PQQ-binding β-propeller repeat proteins and LRR proteins contain multiple polycystic kidney disease (PKD) domains that are usually found in the extracellular segments of archaeal surface-layer proteins with ambiguous functions [20]. Five (e.g., MA4291, MA4305, MA4309, MA4312, and MA4315) contain multiple parallel beta-helix repeats (PbH1) that behave as a stack of parallel beta strands. Proteins containing PbH1 most often are enzymes with polysaccharide substrates [21]. None of the above stated domains are conserved in another five genes, of which MA4293, MA4298, and MA4302 are annotated as hypothetical proteins, while MA4295 and MA4304 are annotated as a cobaltochelatase subunit and DUF4430 domain-containing protein, respectively.

A Arrangement of the gene cluster. The genes labeled with cross marks are pseudogenes in which the N- or C- terminus is disordered. B Domain architectures of the gene cluster analyzed by the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool. Red box in the N-terminus indicates signal peptides. Pink box indicates regions of low compositional complexity. PQQ indicates beta-propeller repeat domain with PQQ as a cofactor. PKD indicates polycystic kidney disease domain. PbH1 indicates parallel beta-helix repeat domain. LRR indicates leucine-rich repeat domain. CobN-Mg_chel indicates magnesium cobaltochelatase. DUF4430 indicates domain of unknown function 4430. C Heatmap analysis of the transcript abundances of the gene cluster from triplicate independent cultures presented as log2 (rpkm) values (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads). The differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. * indicates p < 0.05; ** indicates p < 0.01; *** indicates p < 0.005.

To further validate transcriptomic results, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was utilized to quantify the expression of several key genes encoding Fpo and Rnf complexes and the selected four genes (MA4284, MA4294, MA4305, and MA4310) annotated as PQQ-binding proteins. Transcripts of all the selected genes exhibited upregulation greater than 2-fold (log2(FC) > 1.0) in HA-respiring cells compared to nonrespiring cells. A comparison of differential transcript levels, as analyzed by transcriptome and RT-qPCR, indicated that transcriptomic analysis underestimated the upregulation of those key genes involved in energy conservation of M. acetivorans (Supplementary Table S3).

PQQ is present in the membrane fraction of M. acetivorans

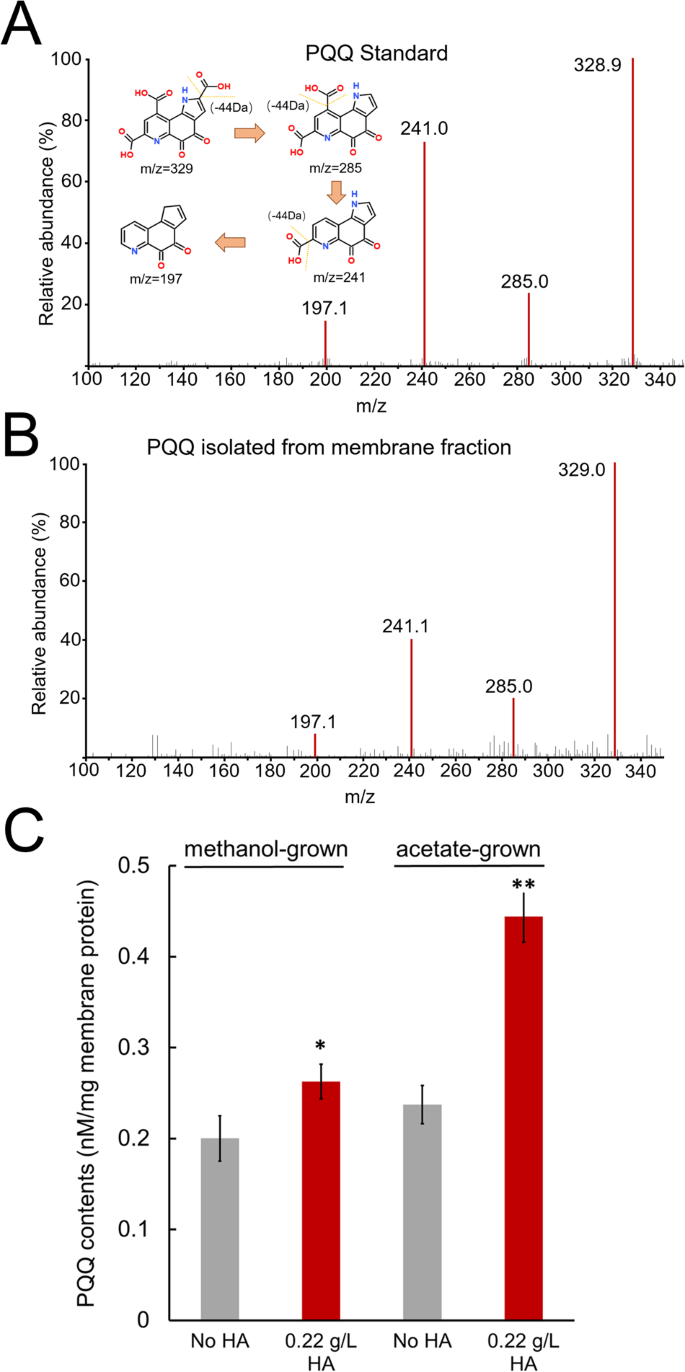

Those genes annotated as PQQ-binding proteins upregulated in HA-respiring cells are of interest because they may possess the redox cofactor PQQ that is a potential candidate for extracellular interaction with HA. Since PQQ has never been identified from the membrane fraction of Methanosarcina spp., we first tried to isolate PQQ based on a previously reported method [22, 23]. The isolated products from the methanol- or acetate-grown membrane fractions exhibited the same retention time in chromatography (Supplementary Fig. S5) and molecular ion peaks at m/z equal to 329, 285, 241 and 197 as the PQQ standard (Fig. 3A, B). According to previous reports [24, 25], the precursor ion of PQQ is m/z 329 [M-H]−, while the PQQ ions that were fragmented by different carboxyl groups are m/z 285 [M-H-CO2]−, m/z 241 [M-H-2CO2]−, and m/z 197 [M-H-3CO2]−. Our results clearly indicate that PQQ is present in the membrane fraction of M. acetivorans. We then quantified the relative PQQ abundances in the membrane fractions by normalizing the total peak areas of the four ions to the known concentration of the PQQ standard. PQQ abundances in the membrane fractions isolated from HA-respiring cells grown with methanol or acetate were significantly higher than those isolated from nonrespiring cells (p < 0.05 or 0.01) (Fig. 3C).

A LC–MS spectrum of standard PQQ. The inset shows the proposed fragmentation pattern of PQQ. B LC–MS spectrum of isolated PQQ from the methanol or acetate-grown membrane. C Quantification of isolated PQQ from the membranes separated from HA-respiring and nonrespiring cells. * and ** indicate significant differences between the control and HA treatments at p < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

Role of PQQ in the extracellular electron transport

Because there is no documented method to directly quantify HA reduction, we used ferrihydrite, a natural form of Fe3+, as an extracellular acceptor to quantify extracellular electron transfer from HA-respiring and nonrespiring resting cells. The resting cells were washed three times to remove residual HA. The initial rates of extracellular electron transfer catalyzed by HA-respiring resting cells were significantly faster than those catalyzed by nonrespiring resting cells as determined by quantifying the reduced amounts of Fe3+ within the first minute (p < 0.01 or p < 0.005) (Fig. 4A). The total reduced amounts of Fe3+ throughout the reaction catalyzed by HA-respiring resting cells were significantly higher than those catalyzed by nonrespiring resting cells (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01) (Fig. 4B). The addition of PQQ or 2-hydroxyphenazine (2-HP), an analog of membrane-bound MP, further significantly increased both the initial and total reduced amounts of Fe3+ (p < 0.005). Given that the amounts of Fe3+ reduction caused by PQQ or 2-HP alone were much lower than the increased amounts of Fe3+ reduction caused by addition of either to the resting cells, the results demonstrated a synergistic effect of PQQ or 2-HP and resting cells in the extracellular electron transport. In addition, the initial and total amounts of Fe3+ reduction catalyzed by the acetate-grown resting cells were significantly higher than those catalyzed by the methanol-grown resting cells under the same condition, which is consistent with the quantification of PQQ isolated from the two types of cells (Fig. 3C).

A Initial reduced rates of Fe3+, which were calculated by quantifying average reduced amounts of Fe3+ within the first minute for three independent assays. B Total reduced amounts of Fe3+, which were calculated by quantifying reduced amounts of Fe3+ throughout the reactions (3 min) for three independent assays. 2-HP and PQQ were used with 100 μM as indicated. * indicates p < 0.05; ** indicates p < 0.01; *** indicates p < 0.005.

PQQ-binding proteins are widely distributed in methanogens

A survey within the archaeal domain retrieved 2684 predicted PQQ-binding β-propeller repeat proteins. They are primarily clustered in Halobacteria (63.4%) and methanogens (20.7%). Of particularly interest, 42.0% of all PQQ-binding proteins were predicted in genus Methanosarcina among methanogens, although only a handful of species were identified in this genus (Fig. 5A). A further search for PQQ-binding proteins in a nonredundant protein database confirmed the finding that homologous are most abundant in the genus Methanosarcina among methanogens. For the MA4284 homologous that have multiple PQQ domains and PKD domains, 90.6% were present in the phylum Euryarchaeota, of which 62.6% are present in Methanosarcina (Fig. 5B). For the MA4290 homologous proteins that have only three PQQ domains, 53.4% were found in the phylum Euryarchaeota, of which 36.7% were present in Methanosarcina (Fig. 5C). The analysis for all the other PQQ-binding proteins were consistent with those for MA4284 and MA4290 (Supplementary Fig. S6). Taken together, these results clearly suggest the evolutionary enrichment of PQQ-binding homologous proteins in methanogens, particularly in Methanosarcina, possibly shedding light into humus respiration of Methanosarcina spp.

A PQQ-binding β-propeller repeat proteins; B Predicted MA4284 homologues; C Predicted MA4290 homologues. Percentage numbers indicate the relative abundances of targeted proteins among the retrieved proteins. Number on nodes indicated bootstrap values.

Discussion

Conventionally, methylotrophic and acetotrophic growth of methanogens is fermentative mode, in which the methyl group of methanol and carbonyl group of acetate are oxidized with electrons transferred to the endogenous electron-accepting methyl group, resulting in methane production [11]. Supplying an extracellular electron acceptor available to methanogens would intuitively inhibit methanogenic growth because electrons are shunted away from methanogenesis. Addition of the quinone-type artificial electron acceptor AQDS has been reported to inhibit the methanogenesis of M. acetivorans [14]. However, the addition of HA with quinone moieties yielded a completely different phenotype from that of AQDS, augmenting methanogenesis and growth. The phenotype of HA-amended culture was consistent with the previously reported Fe3+-dependent respiratory growth of M. acetivorans and M. mazei, which was proposed to supplement growth by fermentative methanogenesis [12, 13]. It was reported that Fe3+ respiration amended with acetate contributed to 36–46% of cellular growth [13]. We therefore calculated the percentages of humus respiration contributing to cell growth during methanogenesis using the growth parameters (Fig. 1). We followed the calculation steps as previously reported [13], which can be found in the Supplementary text. HA respiration contributed to 40.9% of cell growth during acetotrophic growth of M. acetivorans, similar to that of Fe3+ respiration, while HA respiration contributed to 51.4% of cell growth during methylotrophic growth of M. acetivorans. The augmentation of methanogenic growth by extracellular respiration could be explained by the previously reported pathways for methanogenesis and energy conservation in M. acetivorans. Electron transfers to extracellular acceptors have been shown to be able to couple with extra proton and sodium gradients across membrane generated by Fpo and Rnf complexes, respectively [26]. Acetate transport across cellular membrane in acetotrophic growth of M. acetivorans is facilitated by the AceP symporter dependent on proton gradient [16]. Methylotrophic growth of M. acetivorans is dependent on a sodium gradient to drive methyl transfer in the oxidative branch of the methanogenesis [27]. Thus, coupling of extracellular respiration with generation of the proton and sodium gradients could greatly promote utilization of the substrate acetate or methanol for methanogenesis, thereby augmenting the methanogenic growth. In addition, the result showing extracellular electron transport rate stimulated by 2-HP suggests that the membrane-bound MP is probably involved in extracellular respiration (Fig. 4). Given that the redox cycling of MP inevitably drives the generation of proton gradient for energy conservation [28], it is reasonable to speculate that the respiratory energy conserved at MP also contributes to the utilization of substrates for methanogenesis.

MHCs have been well documented to be involved in the extracellular electron transfer of electrobacteria, such as Shewanella and Geobacter [7]. For M. acetivorans, a seven-heme MHC called MmcA, was shown to be responsible for AQDS respiration [14]. However, deletion of the gene encoding MmcA did not disrupt the HA-dependent respiratory growth of M. acetivorans in this work. Considering that the phenotype of HA respiration was distinct from that of AQDS respiration, the extracellular electron transfer mechanism may also be different. Our hypothesis is supported by the result showing that M. barkeri, which is devoid of genes encoding MHCs, is also capable of HA-dependent growth as observed for M. acetivorans. Another study showed that deletion of the only gene encoding MHCs in M. mazei did not disrupt extracellular electron transfer [29]. From the above evidence, it can be found that MHCs are not an indispensable part of extracellular HA reduction in Methanosarcina spp.

Our studies identified previously unexplored PQQ-bind proteins that potential play a role in extracellular HA reduction. As the third type of redox prosthetic cofactor after pyridine nucleotides and flavins, PQQ is a noncovalently bound amino acid-derived quinone cofactor of quinoproteins, particularly for some bacterial cytoplasmic membrane-bound dehydrogenases [18, 30]. Electron transfer between the membrane-bound quinone pools (menaquinone or ubiquinone) and PQQ-containing dehydrogenases usually plays an essential role in bacterial energy-conserving respiration [31]. The extracellular electron transport assays suggest a previously unknown electron transfer from the membrane-bound quinone pool MP to PQQ-containing proteins in methanogens, contributing to an improved understanding of humus respiration. The redox potential of PQQ has been determined to be approximately +90 mV, which is likely to be influenced by its environment in the quinoproteins [32]. Given that the redox potential of MP (e.g., −165 mV) is much more negative than that of PQQ, electrons are likely to be transferred from MP to PQQ. Two previous studies have revealed clues that quinones may be involved in extracellular electron transfer in Methanosarcina spp. One study showed that the genes encoding PQQ-containing quinoproteins were significantly upregulated in M. barkeri cells grown via direct interspecies electron transfer [33], and a second study showed that humic-like compounds were secreted by M. barkeri to facilitate extracellular electron transfer [34]. Here, we first demonstrated that PQQ was indeed present in the membrane fraction of M. acetivorans, and the abundance of PQQ was higher in HA-respiring cells, which is consistent with the transcriptomic analysis. Two genes (e.g., MA3035 and MA4279) annotated as coenzyme PQQ synthesis protein E are present in the genomic DNA of M. acetivorans, which indicates that biosynthesis of PQQ in M. acetivorans is possible.

Ecological implications

The distribution analysis suggests that PQQ-binding homologous proteins are widely distributed in methanogens and most abundant in the genus Methanosarcina, which is one of two genera currently known to perform acetoclastic methanogenesis, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the one billion metric tons of methane produced annually in Earth’s anoxic environments [16]. The PQQ-binding proteins were found in all intensively investigated Methanosarcina spp., including M. acetivorans, M. barkeri, M. mazei, and M. thermophila (Fig. 5), which were isolated from biomass-rich marine or freshwater sediments, where they inevitably interact directly with humus. The HA-dependent respiratory growth involving PQQ extends current understanding of humus respiration in the context of methane dynamics across global sedimentary environments. In addition, the PQQ-binding proteins are also widely distributed in anaerobic methanotrophic archaea (ANME-2 clades), which perform anaerobic oxidation of methane anchored by extracellular reduction of electron acceptors [35]. Our study has sparked a strong interest in whether PQQ play a role in reducing methane emissions by mediating extracellular electron transfer of ANME, in which only MHCs are currently predicted to be involved.

Materials and methods

Organism and growth conditions

M. acetivorans C2A was purchased from the Japan Collection of Microorganisms (JCM, Japan). The strains for ∆hpt and ∆hpt∆mmcA of M. acetivorans were obtained from Dr. Lovley’s group [14]. All M. acetivorans strains were cultured under strict anoxic conditions with an atmosphere of N2/CO2 (80%/20%) in a high-salt medium, as previously reported [36]. M. barkeri was purchased from the German Collection of Microorganisms and cell cultures (DSMZ, German), and cultured under strict anoxic conditions with an atmosphere of N2/CO2 (80%/20%) in a DSMZ methanogenic medium 120 as previously reported [37]. Detailed composition for the high-salt medium and DSMZ medium 120 are described in Supplementary Table S4. Filtered methanol was used as a substrate with a final concentration of 125 mM, while autoclaved sodium acetate was used as a substrate with a final concentration of 90 mM. The 100 mL cultures were inoculated at ratios of 1:100 and 1:10 with methanol-grown and acetate-grown precultures, respectively, and incubated at 37 °C without shaking. HA was purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich (CAS No. 1415-93-6). The properties of the commercial HA have been shown to be similar to those of genuine HA [38]. A 2.2 g/L stock solution of HA was prepared by mixing with autoclaved dH2O followed by adjusting the pH to 7.2 with stirring. The stock HA was then transferred to a serum-stoppered vial and purged with 100% N2 to ensure anoxia. HA was added at the indicated concentrations to the medium using a syringe after thoroughly mixing the stock solution by stirring.

Analytical techniques for growth parameters

The production of methane, total cellular protein concentrations and SEM analyses were measured as previously reported [39]. The cellular ATP concentrations were measured using an ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime, China). The methanol concentrations were measured by a gas chromatograph (GC-2014, Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a DB-FFAP column (internal diameter, 0.32 mm; length, 30 m) and a flame ionization detector. The cultures collected at various time points were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 20 min to separate the medium from the cell pellet. The supernatant was collected, passed through a 0.22 µm filter and was then used in the assays. High-purity nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 3.77 mL/min. The run time was 10.44 min, and the detector temperature was 225 °C. The sodium acetate concentrations were determined by an HPLC system (LC-20A, Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a Hypersil GOLD aQ column and UV–VIS detector. The supernatant was passed through a 0.22 µm filter and acidified with 0.1 M H2SO4. The column temperature was 40 °C. (NH4)2PO4 was used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The run time was 8 min.

Transcriptomic analysis

Cells cultured in the mid-log phase in triplicate were collected by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and genomic DNA was removed using DNase I (TaKaRa). A high-quality RNA sample (OD260/280 = 1.8–2.2, OD260/230 ≥ 2.0, RIN ≥ 6.5, 23 S:16 S ≥ 1.0, >10 μg) was used to construct a sequencing library. RNA-seq strand-specific libraries were prepared following the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit from Illumina (San Diego, CA). Libraries were then size selected for cDNA target fragments of 200–300 bp on 2% Low Range Ultra Agarose followed by PCR amplification for 15 cycles. Paired-end libraries were sequenced by NovaSeq 6000 sequencing (Shanghai BIOZERON Co., Ltd.). The raw paired-end reads were trimmed and quality controlled by Trimmomatic with the required parameters. Clean reads were then separately aligned to the reference genome of M. acetivorans C2A (NC_003552.1) with orientation mode using Rockhopper software. To identify differentially expressed genes between humus-respiring and nonrespiring groups, the expression level for each transcript was calculated using the fragments per kilobase of read per million mapped reads (rpkm) method. The differentially expressed genes between two samples were selected using the following criteria: 1) the logarithmic fold change was greater than 2; 2) the false discovery rate should be less than 0.05.

Determination of PQQ isolated from the membrane fraction

Extraction of PQQ from the membrane was performed based on an amended isooctane extraction method [22, 23]. Lyophilized cell membranes were first prepared. The 100 mL cultures of M. acetivorans were grown with methanol and acetate, respectively, and harvested at exponential phase by centrifugation at 5000 × g and 4 °C for 20 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed twice using 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5 (Buffer A). Then, the cell pellet was resuspended in the Buffer A and sonicated at 100 w for 10 min. The unbroken cells and debris were eliminated by centrifugation at 4000 × g for 10 min. The membranes were obtained by centrifugation at 120,000 × g at 4 °C for 2 h and resuspended in Buffer A. The concentrations of the membrane proteins were determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China). The membrane fraction was then vacuum freeze-dried for PQQ extraction.

The lyophilized cell membranes were immediately resuspended in 20 mL of isooctane and extracted with continuous stirring at room temperature for 3 h. The supernatant was removed, after which fresh isooctane was added to the pellet for a second extraction overnight. After a third extraction for 24 h, the isooctane was discarded from the suspension, and the pellet was completely dried in a vacuum oven. The dried pellet was resuspended in 2 mL of methanol and passed through a 0.22 μm filter. The PQQ standard (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS No. 72909-34-3) was pretreated in the same manner. PQQ isolated from the membrane fraction and the PQQ standard were analyzed by LC–MS (Thermo UltiMate 3000 for HPLC and Thermo LCQ fleet for MS). A total of 5 μL of the sample was autoinjected into the HPLC system in which methanol and water were used as the mobile phases (v:v = 6:4) at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The column temperature was 40 °C, and the column eluent was sent to an ion trap mass spectrometer. Product ion scanning was conducted under electrospray ionization in a positive mode at 320 °C.

Electron transport assays

All electron transport assays were performed in serum-stopped glass vials with a 100% N2 atmosphere. The electron transport activity from the resting cells to ferrihydrite was assayed by monitoring the generation of Fe2+ that chelated with ferrozine, forming a magenta complex with a maximum absorbance at 562 nm. HA-respiring and nonrespiring cells of M. acetivorans were harvested during exponential phase by centrifugation at 5000 × g and 4 °C for 20 min. The cell pellets were thrice washed with Buffer A containing 200 mM NaCl (Buffer B) to acquire the resting cells. The standard reaction mixture (10 mL) contained 1.6 × 108/ml resting cells in Buffer B. 100 μM of 2-HP or PQQ were added as indicated. Ferrihydrite was added to start the reaction at a final concentration of 1.25 mM. A total of 50 μL of the reaction mixture was collected at various time points and reacted with 1.0 mM ferrozine solution for the absorbance assay.

Phylogenies analysis and distribution patterns of PQQ-binding proteins in Archaea

The representative species and 16S rRNA gene sequences were obtained from the GTDB R06-RS202 (Genome Taxonomy Database) and SILVA SSU 138.1 (high quality ribosomal RNA database). The phylogenetic trees of the 16S rDNA sequences were constructed by using the maximum likelihood method in MEGA 7.0. The sequences of the PQQ domain-containing proteins were downloaded from the SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool) database. The putative homologs were found by performing BLAST analysis from the nonredundant (NR) protein database. The proteins were clustered with USEARCH with a 95% similarity threshold to remove redundant proteins present in the protein databases. The cluster centroids and cluster members not from the same species of centroids were retained for further analysis.

Responses