Hybrid magnon-phonon crystals

Introduction

An artificial periodic structure, or artificial lattice, is a powerful tool to modulate the coupling between different degrees of freedom. For example, the electrons in the Moiré superlattices of overlapped two layers with a specific arrangement of points can form superconducting1 or quantum anomalous Hall states2,3. Designed lattices enhance the light-matter coupling4, enabling strong nonlinear effects4,5 and controllable laser emission with high efficiency6,7. One may use artificial lattices to tune the coupling through several strategies. Firstly, a periodic structure induces coherent scattering on a wave, creating a designed band dispersion and wave function. The coupling between two waves, related to their band dispersion and wavefunction, is thus naturally controlled by the designed artificial lattices, even if the coupling strength is still uniform. Meanwhile, the periodic structure may directly control the local coupling strength, inducing a periodical (non-uniform) interaction landscape, e.g., the periodic interlayer coupling in the Moiré superlattices8,9. Such non-uniform coupling strength can induce more sophisticated states, like those with entangled spins and valleys in the twisted bilayer graphene.

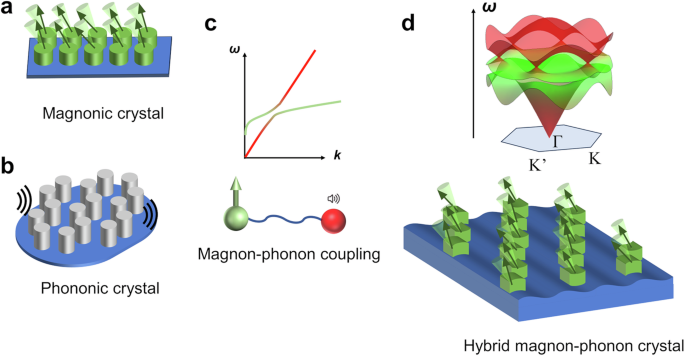

While the ability of artificial lattices to tune the coupling is mainly demonstrated in electronic and photonic coupling systems, the general principles should apply to various artificial lattices with coupled degrees of freedom. In spintronics, spin waves formed by the collective motion of the spin degree of freedom are tuned in artificial lattices, known as magnonic crystals (Fig. 1a). While spin waves in uniform magnetic materials10 show abundant tunablility via magnetic field11,12 and ferroelectricity13, the magnonic crystals can additionally obtain a significantly different spectrum, such as tunable band gaps14,15,16,17,18,19. Modern nano-techniques enable magnonic crystals with a lattice size in sub-μm scale, leading to the application in various devices processing information20,21,22, especially at GHz frequency. At the same frequency range and characteristic size scale, another significant artificial lattice is the phononic crystal (Fig. 1b) based on surface acoustic wave (SAW). Various physical phenomena, including Klein tunnelling23 and topological edge states24,25 have been observed in phononic crystals. In phononic crystals with sub-μm scale lattice size, the phononic valley Hall effect and phononic valley Hall edge states at GHz frequency are also demonstrated26,27,28,29.

a Schematic of a magnonic crystal made of periodically patterned magnetic materials. b Schematic of a phononic crystal, where periodical scatter centers tune the transport of the acoustic waves. c Magnon-phonon coupling and the resulting magnon-phonon hybrid spectra. An avoid-crossing point can appear when both frequencies and wavevectors meet. d Concept of a hybrid magnon-phonon crystal, including the periodic acoustic scatter centers made of magnetic materials in the real space (lower panel) and the magnon-phonon hybrid band structure in the reciprocal space (upper panel).

Magnons and phonons inherently couple due to the magnetoelastic interactions, which generally exist in magnetic materials (Fig. 1c). SAW can, therefore, excite ferromagnetic resonance30 and spin pumping31, and the time-reversal symmetry breaking due to magnons can induce nonreciprocal-transmission-of phonons32,33,34,35,36. In the magnon-phonon band structure, when the magnon band and the phonon band meet with the same wavevector and frequency, magnon-phonon coupling hybridizes the two waves, opening a gap, showing an anticrossing in the spectra37,38. Due to the distinct symmetry properties of the magnetoelastic interaction, this gap opening can be associated with Berry curvature39, enabling topological magnon-phonon hybrid excitations40 and even chiral edge states40,41.

Gathering the functionality of magnonic crystals, phononic crystals, and magnon-phonon coupling, as well as borrowing the successful concepts in the electronic and photonic coupling in artificial lattices, the combination of magnonic and phononic crystals may provide various emergent phenomena and benefit both the fields of phononic and magnonic crystals. Here we define a hybrid magnon-phonon crystal as an artificial lattice that exhibits a phononic and/or magnonic band structure and possesses magnon-phonon coupling. A typical example is shown in Fig. 1d where periodic acoustic scattering centers are made of magnetic materials. In this perspective, we will introduce some recent progress in the relevant fields, to show that the artificial lattice is a powerful tool to modulate the magnon-phonon coupling and discuss the possible structures of a hybrid magnon-phonon crystal. We then discuss future topics to be explored based on the physical properties of the hybrid magnon-phonon crystals, combined with possible experimental characterizing techniques and potential applications.

Recent progress on magnon-phonon coupling in artificial lattices

The simplest combination of the magnonic and phononic crystals is integrating the band gaps of the two excitations. In 2012, V. L. Zhang et al. reported the coexistence of the magnonic and phononic gaps in a linear periodic array of Fe and permalloy using the Brillouin spectroscopy42. However, the magnon-phonon interaction was deliberately avoided in this study to separate the magnonic and phononic excitations.

The recent progress in magnon-phonon coupling shows abundant intriguing phenomena and possibilities43,44. Coupling the circular polarization of the Rayleigh SAW to the right-handed magnetization precession creates nonreciprocal SAW transmission, i.e., the forward and backward SAWs have different attenuation because they carry opposite circular polarization and excite magnetic resonance with different efficiency. Various approaches can achieve such nonreciprocity, including the shear strains35, magneto-rotation coupling33, Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction36,45, and synthetic antiferromagnetism34,46. Nonreciprocity can be understood as the magnetic control of the SAWs. In turn, acoustic control of the magnetization direction was reported via phonon-spin angular momentum transfer47,48. This SAW-induced spin torque can also be detected electrically49. Meanwhile, the SAW-based devices have also been extended to detect the magnon-phonon coupling in Van der Waals antiferromagnets50, achieve on-chip strong magnon-phonon coupling in room temperature38, assist magnetic domain wall motion51, create52 and manipulate53 skyrmions. Thus, instead of separating the magnonic and phononic excitations, combining the magnon-phonon coupling43,44 with the artificial lattice may be more competitive in bringing about new opportunities.

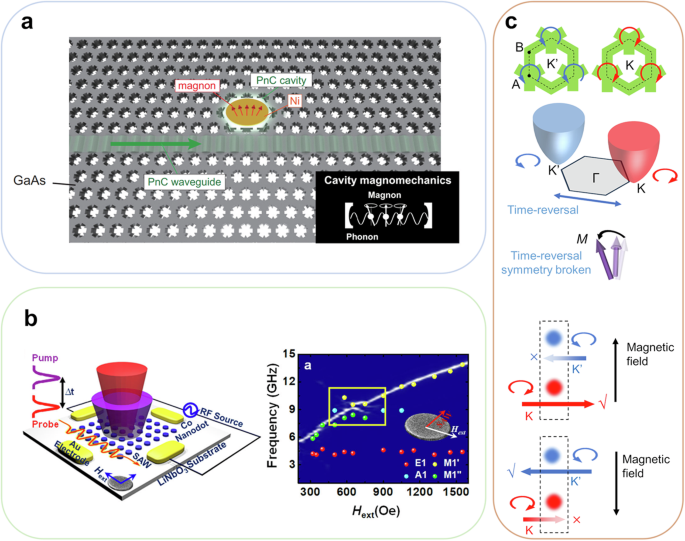

A first example is the engineering of a phononic crystal for tuning the magnon-phonon coupling. The strong demand for high-quality cavities in magnon-phonon coupling triggers an approach to manipulating magnons employing a defect in a phononic crystal known as a high-quality acoustic cavity54,55,56. Hatanaka et al. studied the cavity magnomechanics using phonons confined in a defect within a snow-flake-shaped phononic crystal57 (Fig. 2a). Their optical interferometry experiments demonstrate that the phononic crystal cavity allows the spatial confinement of phonon energy, as well as the generation of different modes, with different strain distribution across the cavity. Precise manipulation of magnetoelastic interactions is then achieved by selectively tuning the phononic crystal resonance modes and controlling the external magnetic fields and changes in magnetization direction (angle). Hence, phononic crystals can precisely manipulate the magnons through phonon confinement, which has potential applications in signal processing.

a Engineering a phononic crystal for the magnon-phonon coupling. In the defect of a snow-flake-shaped phononic crystal, phononic energy is confined, and the cavity phonon mode can be selected. A magnetic Ni island is placed inside the cavity, allowing the magnon-phonon coupling. Copied from57 with permission of American Physical Society. b Engineering a magnonic crystal for the magnon-phonon coupling. The time-resolved magneto-optical Kerr effect detects coherent magnon-phonon-magnon coupling within a two-dimensional artificial magneto-elastic crystal. Anticrossing shows the strong coupling between a Kittel-type magnon mode and a non-Kittel magnetoelastic mode driven by SAW. Edited from58 (open access). c Combining the phononic and magnonic crystal for new functionality with the magnon-phonon coupling. The phononic crystal has K and K’ valleys as time reversal pairs with opposite chirality, and the magnons break the time-reversal symmetry so that selective control of the valley phonon transport is allowed: an upward magnetic field enables the transport of the K valley phonons. It blocks the K’ valley phonons, and a downward magnetic field behaves oppositely.

As phononic crystals can tune the magnon-phonon coupling, it is natural to look at the opposite approach, i.e., to tune the coupling via engineering a magnonic crystal. Another recent work by Majumder et al. explores the hybridization of phonons with magnonic crystals58. A coherent magnon-phonon coupling within a two-dimensional artificial magneto-elastic crystal is observed by the time-resolved magneto-optical Kerr effect technique (Fig. 2b). Central to their discovery is the formation of binary magnon polarons, arising from the coherent coupling between two distinct Kittel-type magnon modes and a non-Kittel magnetoelastic mode, with the latter driven by SAW. The strongest coupling is achieved through the matched frequencies and wavevectors of the three modes, leading to a perfect phase match. Notably, the strong coupling exhibited significant anisotropy due to the spatial asymmetry of the arrays, with the coupling strength and the consequent formation of binary magnon-polarons being highly dependent on the direction of the SAW relative to the axes of the nanomagnets. The precise design and manipulation introduce strong coupling at room temperature, showcasing a novel method for controlling magnonic and phononic interactions.

Now, we turn to a more dramatic phenomenon combining the two types of crystals and the properties of the magnetoelastic interaction. As shown in Fig. 2c, in hexagonal phononic crystals, one can introduce asymmetric A site and B site in a unit cell (the dash line hexagon). In the reciprocal space, inequivalent high-symmetry points K and K’ are in the first Brillion zone. The band structures at these k points are known as valleys, like electronic valleys in the hexagonal graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides. Phonon modes at the K and K’ points in the Brillion zone are called K and K’ valley phonons, labeled in red and blue bands, respectively.

The K and K’ valleys are degenerated as they are time-reversal pairs, i.e., they have the same frequency and different k vectors. While magnons are introduced in the same lattice, the time-reversal symmetry can be broken. Hence, a valley-selective phonon-magnon scattering was achieved (Fig. 2c). With an upward magnetic field, phonons in the K valley can pass through the lattice more efficiently. On the contrary, phonons in the K’ valley get more scattering from the magnons. The situation reverses when the magnetic field is reversed, as the phonons in the K’ valley will now pass more efficiently59.

The selective interaction between magnons and phonons is achieved by introducing local circular polarization in the phonon modes with broken spatial inversion symmetry. The asymmetric A and B sites lead to opposite local circular polarization at the A site for the K and the K’ valley phonons. Experimentally this is achieved by patterning inversion-symmetry broken lattice using e-beam lithography, and exciting the phonon modes at the corresponding frequency, i.e., matching the wavelength of the applied acoustic wave and the lattice size59. As magnons are always right-handed, they can only couple to right-handed phonons (K’ valley) when the magnetization is upward and to left-handed phonons (K valley) when the magnetization is downward. Such helicity mismatch effect in the magnon-phonon coupling is an important tool for nonreciprocal SAW devices32. A similar interaction is also observed in a Van-der Waals antiferromagnet at low temperature60. Through this effect, magnons can serve as a tool to manipulate the transport of the valley phonons.

Perspectives on hybrid magnon-phonon crystals

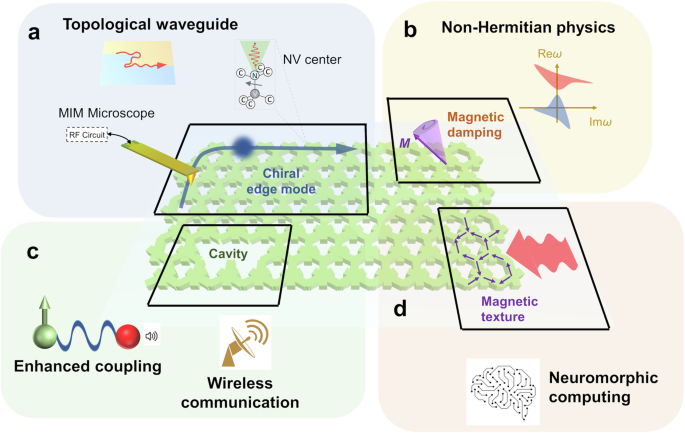

The hybrid magnon-phonon crystals thus enrich the toolbar to modulate the magnon-phonon coupling, as well as providing new opportunities for the magnonic and phononic crystals (Fig. 3). Due to relatively sizeable magnetic damping, magnons usually have a short propagation length, limiting the scale of the magnonic crystals. However, phonons provide a much longer lifetime and propagation length, so magnon-phonon coupling enables magnon-phonon polarons to propagate long distance61. Hence, a hybrid magnon-phonon crystal can combine the advantage of the long-life phonons and the time-reversal symmetry-breaking nature of the magnons59 and may open the avenue for more intriguing states. Since the magnetoelastic interaction can give a magnon-phonon hybrid band structure finite Berry curvature, leading to a Chern insulator-like state with topological edge transport40, a properly designed hybrid magnon-phonon crystal may also own chiral edge states (Fig. 3a). Note that the traditional measurement of ports transmission or reflection via a Vector Network Analyzer may not be sufficient to conclude the chiral edge states directly. Instead, technologies that can locally detect the strain of the phononic crystal or dynamic magnetization state on the device surface are needed, such as characterizing strain through transmission-mode microwave impedance microscopy (TMIM)27 or applying optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) to characterize the stray field emitted by the magnonic crystal through the quantum sensor NV-center62,63. Developing the tunable topological edge transport in the hybrid magnon-phonon crystals will advance the waveguides in wave-based computing.

a Designing band structures with nonzero Chern number with the magnetoelastic interaction may enable topological chiral edge modes, which can be detected by a MIM microscope or a N.V. center and help develop tunable waveguides. b The imaginary frequency induced by the magnetic damping provides opportunities for non-Hermitian physics. c Defect-induced cavity can enhance magnon-phonon coupling, benefiting coherent information processing and the magnetoelectric antennas for wireless communication. d Spin-ice-type magnetic textures in artificial lattices interacting with SAWs may be used for neuromorphic reservoir computing.

While the magnetic damping limits the magnon lifetime and is usually unfavorable, the resulting loss makes the magnon-phonon hybrid system inherently non-Hermitian64,65. As shown in Fig. 3b, considering the magnetic damping, the imaginary frequency can emerge in the magnon-phonon hybrid band structures. By engineering the hybrid band structures and creating finite areas in the real- and imaginary-frequencies spectra, the non-Hermitian skin effect can be achieved66,67,68. The surface nature of the SAW can also lead to non-Hermicity69. Hence, the hybrid magnon-phonon crystals may also provide a platform for exploring the non-Hermitian physics70.

The phononic crystals can tune the strain components and their distributions57,59. The recently reported strong magnon-phonon coupling38 emphasizes the crucial role of strain components in reaching the strong-coupling regime. Furthermore, the defect in a phononic crystal acts as a cavity54,55,56 that can confine the energy of the acoustic mode (Fig. 3c). Such confinement effect can be achieved or enhanced through engineered flat bands, e.g., by creating moiré patterns71. Hence, we can expect that through engineering the lattice symmetry and band structure, making cavities with stronger confinement ability, a hybrid magnon-phonon crystal can contribute to further enhancing the magnon-phonon coupling strength, and tuning nonlinear effects4,5. The improved coupling can benefit coherent information processing and the miniaturization of magnetoelectric antennas for wireless communication72,73,74.

Another possible direction for hybrid magnon-phonon crystals is the combination with spin textures. It is known that artificial magnetic lattices can host rich ground states, known as artificial spin ice, due to the dipolar interaction75. The magnetic textures lead to rich spin wave fingerprints76,77. The complexity of magnetic textures is a widely used resource for neuromorphic computing called reservoir computing78,79. As the SAWs have shown the ability to probe spin waves and manipulate magnetizations47,80, and the periodic artificial magnetic lattice can also tune the SAW spectra as a phononic crystal, combining SAW with artificial spin ice may create more opportunities for spin-ice-based reservoir computing (Fig. 3d).

We finally briefly introduce the simulation techniques for hybrid magnon-phonon crystals. For GHz on-chip acoustic devices, which mainly use the SAW-based phonons, the acoustic dynamic is described by the elastic equation59 and widely solved via the finite element method with the multi-physics simulation software COMSOL. In COMSOL simulation81, one can design a complete unit cell, including a piezoelectric substrate and a lattice pattern. The “Floquet periodicity” boundary condition is then applied to obtain the band structure (eigenfrequency) of the unit cell lattice and the excited eigenmodes. This approach allows the design and analysis of the lattices with different symmetries. One may not apply periodic boundary conditions for the cavity but use the transmission line model82. The entire pattern of the cavity can be placed between the on-chip input and output to explore the response of the cavity pattern. One can use the same modeling but modify the applied physics module to include the magnon bands. For the micromagnetic module, the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation should include an effective field induced by magnetoelastic coupling, and the equation of motion for the mechanical module should include the magnetoelastic coupling83.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the general principles to tune the coupling between two degree-of-freedoms via artificial lattices can apply to the hybrid magnon-phonon crystals. It is then allowed to harvest the property of magnon-phonon coupling, the time-reversal symmetry-breaking nature of magnons, and the long lifetime of phonons in an integrated system. By benefiting from the advanced spectral measurement and local characterization techniques, the hybrid magnon-phonon crystals can provide novel opportunities for topological edge transports in tunable on-chip waveguides. The rich properties, including the imaginary frequency due to the magnetic damping, cavity effect of the defects in a lattice, the artificial spin ice-type magnetic textures, enable the hybrid magnon-phonon crystal as a potential platform for non-Hermitian physics, magnetoelectric antennas, reservoir computing, etc. Hence, we look forward to further advancement in this area by exploring the above possibilities.

Responses