Hypertension inhibition by Dubosiella newyorkensis via reducing pentosidine synthesis

Introduction

Hypertension is a major risk factor for stroke, coronary heart disease, and many other adverse medical conditions. Depending on whether identifiable causes are present, hypertension can be classified as primary or secondary hypertension. Primary hypertension, or essential hypertension, arises from defused medical conditions and is the result of complex interactions between genes and environmental factors, whereas secondary hypertension, or incident hypertension, is rooted in known medical conditions such as kidney disease and endocrine imbalance. Lifestyle management, especially diet change and salt intake reduction, are currently the most available and effective in treating hypertension due to the extremely complicated pathogenesis of hypertension, including inflammation, gut microbiome, genetic variations in salt sensitivity and other factors. Thus, understanding the detailed mechanisms underlying HSD and hypertension is an urgent and unmet medical need.

Dietary sodium reduction has been widely incorporated into national and international dietary recommendations intended to prevent chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The relationship between dietary habits and NCDs has been extensively recognized for a long time without the discovery of its underlying mechanisms. However, controversy remains regarding whether reduced salt intake lowers blood pressure and reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and mortality1,2. HSD could induce hypertension through multiple undiscovered mechanisms. However, the relationship between HSD, gut microbiota and endothelial dysfunction has aroused a lot of attention. Emerging data indicate a correlation between gut microbiota and CVDs, including salt-sensitive hypertension. Low sodium intake effectively reduced patients’ blood pressure and significantly increased the level of gut microbiota-related short-chain fatty acids in almost 150 untreatable patients3. With emerging evidence of its involvement in endothelial dysfunction and different CVDs, the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition holds therapeutic promise for treating them4. As research into HSD and CVDs progresses, ever more intestinal bacteria and metabolites have been found to play important roles in the development and prevention of hypertension5,6. This is consistent with our previous findings that gut microbiota are involved in the VK2-inhibited renin-angiotensin system in salt-induced hypertensive mice and that ATF4 regulates the balance of gut microbiota, which leads to endothelial dysfunction7. Data from gut microbiota can help us develop new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for salt-sensitive diseases5. The gut microbiota exhibit “salt response” properties in CVDs development. Yan et al.6 have demonstrated that gut microbiota could affect steroid hormone levels by applying fecal microbiota transplants to modulate blood pressure. In clinical practice, however, the gut microbiome’s long-term genetic stability should be considered in relation to dietary intake8,9. A clinical study found that gut microbiome composition is independent of dietary input due to the gut microbiome’s stability10. Consequently, there is no direct evidence that gut microbiota promote or prevent CVDs, due to the lack of preclinical studies in sterile hosts. Dubosiella is a genus of Firmicute in the family Erysipelotrichaceae. Dubosiella newyorkensis (NYU-BL-A4) is the only species of the genus Dubosiella and a newly identified gut symbiont bacterium that is thought to be implicated in obesity and other diseases11,12. In our previous study, we demonstrated that Dubosiella is highly responsive to HSD and vascular endothelial injury in C57BL/6J mice, and significantly affected HSD induction via fecal microbiota transplantation13.

In the present study, we hypothesized that HSD induces hypertension or endothelial injury through modulation of gut microbiota, especially the Dubosiella newyorkensis. We tended to explore the causality between HSD and endothelial dysfunction in conventional (Conv) and germ-free (GF) mice. Multiomics analysis has found Dubosiella newyorkensis was decreased in the development of HSD-induced hypertension in Conv mice. Dubosiella newyorkensis could protect blood pressure in HSD-induced Conv mice and verified in GF mice. Additionally, the molecular mechanisms of the potential HSD biomarker involved in its adaptive regulation of vascular physiology were ascertained via whole-genome sequencing of Dubosiella newyorkensis. The present study describes the gut microbiota as a new way to regulate HSD-induced Conv and GF mice.

Results

Ratio of plasma NO/ET-1 decreased hypertension by high-salt diet in mice

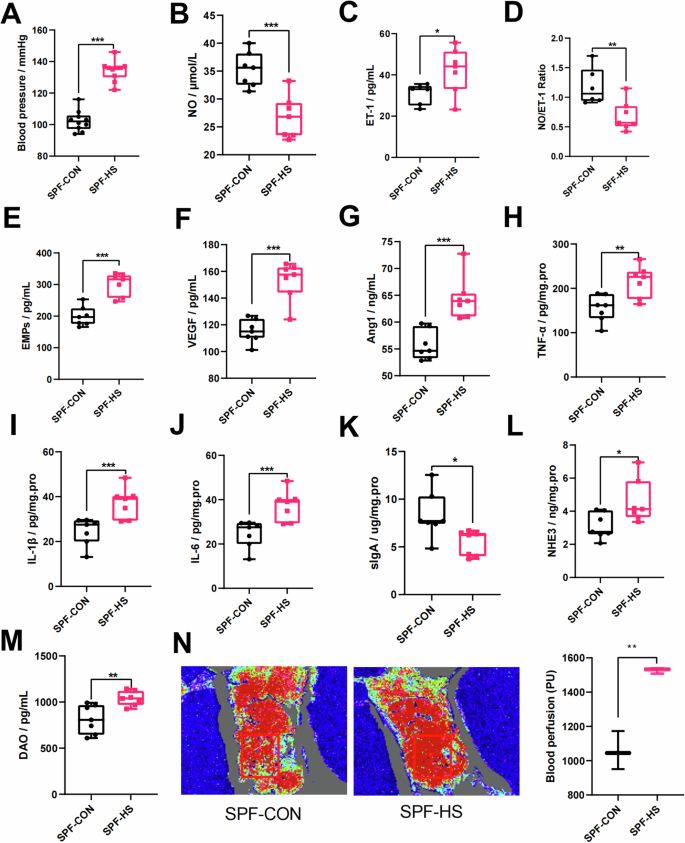

To verify the role of HSD in mediating hypertension, Conv mice were fed either normal or high-salt diets for 4 weeks. After HSD, we found significant blood pressure elevation in the Conv mice compared with the Con group (Fig. 1A). To further confirm the endothelial dysfunction in HSD-induced Conv mice, we also detected the vasoconstriction and vasodilation markers. The vasodilation marker NO was significantly decreased in Conv mice after HSD feeding, while the vasocontraction marker ET-1 was significantly elevated (Fig. 1B, C). Interestingly, NO/ET-1 was lower in Conv mice fed HSD after 4 weeks (Fig. 1D). The vascular endothelial activators, including EMPs, VEGF, and AngI, were also significantly increased in HSD-fed Conv mice (Fig. 1E–G). Together, these results suggested that HSD attenuates the changes in blood pressure through an endothelium-dependent dilation dysfunction manner.

A The changes in blood pressure (n = 10). B–D The changes in vasoconstriction and vasodilation-related factors, such as NO (B), ET-1 (C), and NO/ET-1 (D). E–G The changes in vascular endothelial active factors, such as EMPs (E), VEGF (F), and Ang1 (G). H–J The changes in immunity and inflammation-related factors, such as TNF-α (H), IL-1β (I), IL-6 (J), and sIgA (K). L–N The changes in the intestinal vascular barrier, such as NHE3 (L), DAO (M), and intestinal perfusion (N). The intestinal perfusion in the four groups (n = 3) was evaluated with laser speckle flowmetry, with red indicating high perfusion and high flux and blue indicating low perfusion and low flux. CON control group, HS high-salt diet group, NO nitric oxide, ET-1 endothelin-1, EMPs endothelial microparticles, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, AngI angiotensin I, IL-1β interleukin-1β, IL-6 interleukin-6, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α, sIgA secretory immunoglobulin A, DAO diamine oxidase, NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger type 3. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; ns, no statistical significance; n = 6–7.

Previous studies also indicated that HSD is associated with impaired intestinal mucosal immune function, intestinal inflammation, and intestinal permeability5,14. We then wonder whether HSD could induce endothelial dysfunction by manipulating inflammation. The results showed that HSD could induce significant elevation of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in Conv mice (Fig. 1H–J). We also found a significant decrease of sIgA in Conv mice after HSD fed (Fig. 1K). The intestinal permeability and salt absorption were also significantly increased in HSD-treated Conv mice by detecting the DAO and NHE3 levels (Fig. 1L, M). To investigate intestinal perfusion, the blood flow on the intestinal surface in Conv mice was measured. Figure 1N illustrates that the blood flow on the intestinal surface was increased in HSD-induced Conv mice. Taken together, these results demonstrated that HSD could induce endothelial dysfunction and hypertension through orchestrating intestinal function.

Metabolic profiles changed in hypertension

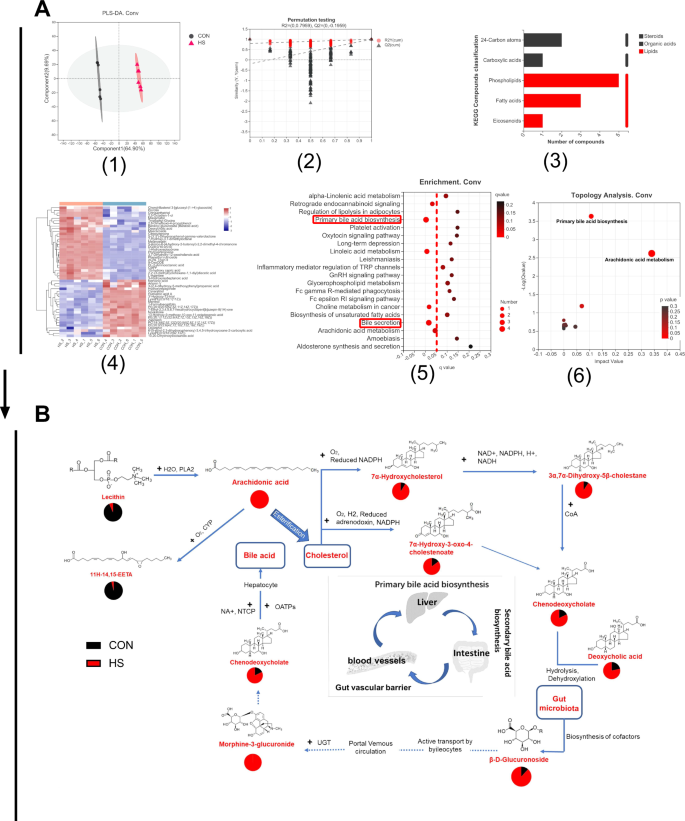

Serum metabolites are considered important components of gut microbiota15,16. Untargeted metabonomic was conducted to investigate the serum metabolites in HSD-induced Conv mice. The metabolite differences in Conv mice that were induced by HSD are shown in Fig. 2A. The PLS-DA plot shows a clear difference between Conv mice that were fed HSD and normal diet (Fig. 2A1), and the permutation testing of the PLS-DA analysis illustrates a robust and reliable metabolite difference (Fig. 2A2). The results indicate that HSD affects metabolites in Conv mice. Figure 2A3 demonstrates that the KEGG compound classification of the different metabolites mainly indicates phospholipids and fatty acids, showing that the metabolites were mainly concentrated in lipid metabolism. According to these findings, HSD could induce 283 different types of metabolites in the serum of Conv mice, with 169 of them being upregulated and 114 downregulated (Supplementary Table 3); the top 50 metabolites are shown in Fig. 2A4. The KEGG pathway of the differential metabolites is mainly enriched in primary bile acid biosynthesis and bile secretion (Fig. 2A5). Furthermore, the topology analysis of the differential metabolites mainly yielded primary bile acid biosynthesis and arachidonic acid metabolism compounds (Fig. 2A6). The results reveal the detailed metabolic pathway affected by HSD in Conv mice.

A Metabolite differences in conventional (Conv) mice induced by HSD (n = 6). A1 The PLS-DA plot. A2 Permutation testing of the PLS-DA analysis. A3 The KEGG compound classification. A4 The heatmap of metabolites. A5 The enrichment of metabolites. A6 The topology analysis. B The metabolic cycle pathway of the HSD in Conv mice based on KEGG mapping of Genome. Net: map00120 with a 4/21 ratio of metabolites annotated to the pathway, including chenodeoxycholate (C02528), 7alpha-hydroxycholesterol (C03594), 3alpha,7alpha-dihydroxy-5beta-cholestane (C05452), and 7alpha-hydroxy-3-oxo-4-cholestenoate (C17337) (q < 0.05); map0497 with a 4/21 ratio of metabolites annotated to the pathway, including beta-D-glucuronoside (C03033), deoxycholic acid (C04483), morphine-3-glucuronide (C16643), and chenodeoxycholate (C02528) (q < 0.05); map00590 with a 3/21 ratio of metabolites annotated to the pathway, including arachidonate (C00219), lecithin (C00157), and 11H-14,15-EETA (C14813) (q < 0.05). CON control group, HS high-salt diet group.

To further investigate the metabolic pattern of gut microbiota in HSD mice, the metabolites were mapped to metabolic pathways by GenomeNet software. In Conv mice, there were 21 differential metabolites (p < 0.05) in the metabolic pathways of HSD, and the main metabolic pathways include map00120, primary bile acid biosynthesis; map04976, bile secretion; and map00590, arachidonic acid metabolism (q < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 5). The metabolites mapped in the pathways showed that HSD mainly interfered with the primary bile acid synthesis pathway in Conv mice, specifically affecting the liver–intestinal circulation. Under the action of gut microbiota, HSD led to a significant decrease in lecithin and a significant increase in arachidonic acid production, which might be related to secretory phospholipase A2 (pla2g). In addition, arachidonic acid esterification induced abnormal cholesterol metabolism, thus affecting the production of primary bile acids (Fig. 2B). The gut microbiota is involved in the biosynthesis of secondary bile acids, which are transported into the peripheral circulation through ileal cells to further interfere with bile acid secretion and arachidonylation-related lipid metabolism (Fig. 2B).

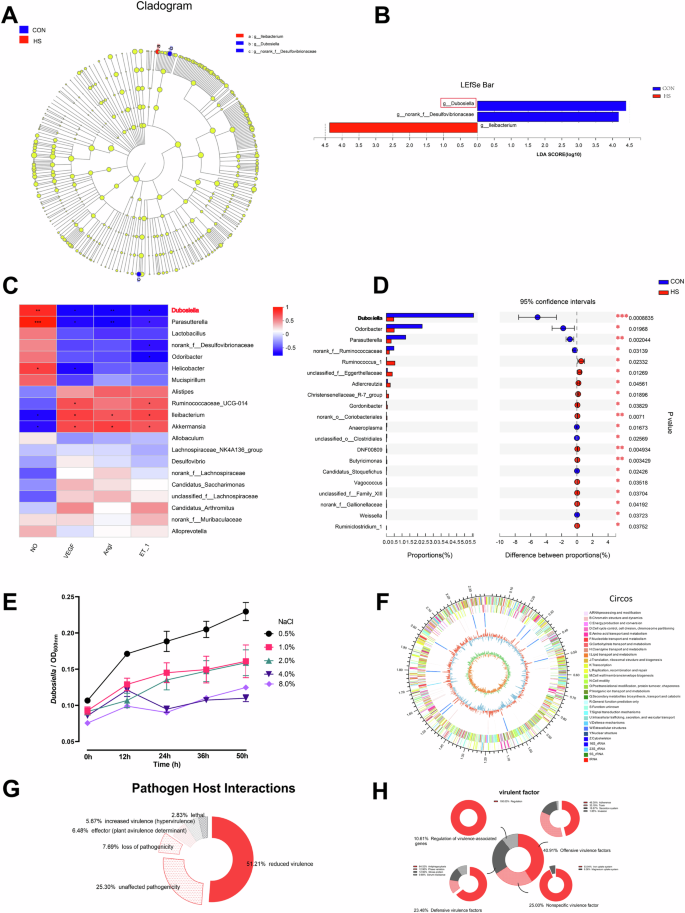

Potential probiotic Dubosiella is highly sensitive to salt in hypertension

Dubosiella is the dominant genus of bacteria in the feces samples from HSD-induced mice (Fig. 3A, B). Dubosiella was one of the three gut symbiotic bacterial genera that responded to HSD (Fig. 3B). Feeding HSD for 4 weeks could significantly reduce the colonization of Dubosiella in the gut (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). There is a significant correlation between the genera Parasutterella, Lactobacillus, Dubosiella, and Mucispirillum and all vascular endothelial factors including NO, VEGF, AngI, and ET-1 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3C). The result of FISH, involved 24 fecal samples obtained from patients with high blood pressure and healthy control, revealed that the relative ratio of Dubosiella was low expression in patients with high blood pressure compared with the healthy control (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Dubosiella newyorkensis, as the only species of the genus Dubosiella, was used to determine salt tolerance in vitro. The result was indicative of a strong NaCl concentration resistance that given 4.0% and 8.0% NaCl for 24 h, Dubosiella newyorkensis solution content evidently decreased (Fig. 3E). Then the whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of Dubosiella newyorkensis was performed with the Illumina Hiseq and PacBio methods. Based on the 16S rRNA sequence, the 19 strains closest to Dubosiella newyorkensis at the species level were selected, and the NJ (neighbor-joining) method was selected with MEGA 6.0 software to construct a phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. 2A1). Based on 31 house-keeping genes (dnag, FRR, INFC, Nusa, PGK, pyrG, RPLA, rplb, RPLC, RPLD, rple, rPLF, rplk, rpll, rplm, rpln, rplp, RPLS, rplt, RPMA, rpoB, rpsB, RPSC, rpse, rpsi, rpsj, rpsk, rpsm, RPSS, SmpB, and TSF), the 19 closest strains were again selected to construct a phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. 2A2). After Gram staining, observation under a transmission electron microscope (TEM) showed that Dubosiella newyorkensis is a rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium (Supplementary Fig. 1B). The GC_depth distribution map demonstrated no obvious GC bias in sequencing and most points were concentrated in a narrow range, indicating no pollution in the sample (Supplementary Fig. 2C). The total genome size was 2.26679706573 MBP, and the average gene length was 858.73 BP, G+C (%), as sequencing showed. The GC content of all scaffolds in each genome was 42.72%; the average GC content was 43.1%; the gene/genome percentage was 89.49%; the intergenic region length (BP) was 249,831; GC content in the intergenic region was 39.49%; the intergenic region percentage in the genome was 10.51; the NR (Non-Redundant Protein Database) was 2477; Swiss-Prot: 1581; Pfam: 1895; COG: 1954; GO: 1831; and KEGG: 1173 (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, 51.21% of the genes identified in the analysis of the pathogen–host interaction showed reduced virulence (Fig. 3G). The detailed virulence factor, based on the virulence factor database (VFDB), is shown in Fig. 3H. All these findings suggest the potential probiotic properties of Dubosiella newyorkensis which is highly sensitive to salt.

A, B LDA effect size (LEfSe) analysis between subsets of high-salt diet in conventional (Conv) mice, LDA = 4. C The correlation analysis of bacteria genus and vascular endothelial factors. D The changes in the relative abundance of Dubosiella after 4 weeks of high-salt diet treatment in Conv mice. E The salt tolerance test results of Dubosiella newyorkensis. F The whole Dubosiella newyorkensis genome. From the outer to the inner circle, each circle indicates information regarding the genome of the forward CDS, reverse CDS, forward COG function classification, reverse COG function classification, nomenclature and locations of predictive secondary metabolite clusters, and G+C content. The red sections indicate that the GC content of the region is higher than the average GC content of the whole genome. The higher the peak value, the greater the difference between the GC content and the average GC content. The blue sections indicate that the GC content of the region is lower than the average GC content of the whole genome. The higher the peak value, the greater the difference between the GC content and the average GC content and GC skew. G The analysis of pathogen–host interactions. H The analysis of virulence genes. Statistical significance was determined using t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; n = 6.

Supplementing Dubosiella newyorkensis prevents the rise of blood pressure in hypertensive mice

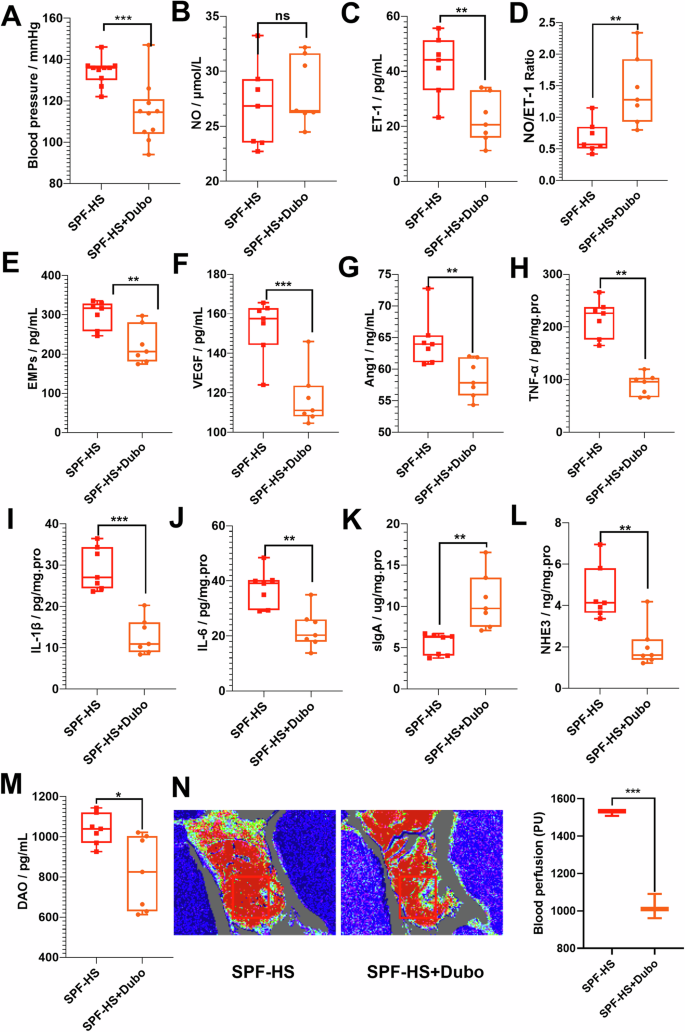

To explain the role of gut microbiota in the development of HSD-induced hypertension to verify the protective effects of Dubosiella newyorkensis against this process, Dubosiella newyorkensis was orally supplemented during the formation of HSD-induced hypertension. This study further verified that Dubosiella newyorkensis effectively inhibits the increase of blood pressure caused by HSD in Conv mice (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, increased NO and significantly decreased ET-1 were observed in HSD-induced Conv mice after supplementary Dubosiella newyorkensis (Fig. 4B, C). Moreover, imbalanced NO/ET-1 was still observed in HSD-induced Conv after supplementary Dubosiella newyorkensis (Fig. 4D). The results indicate that the imbalanced NO/ET-1 was the common mechanism in the effect of Dubosiella newyorkensis on HSD-induced Conv mice. Figure 4E–G indicated that EMPs, VEGF, and AngI were lower in HSD-induced Conv mice after supplementary Dubosiella newyorkensis (Fig. 4E–G). Decreased TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and increased sIgA were found in the HSD-induced Conv mice after supplementary NYU-BL-A4 (Fig. 4H–K). Decreased NHE3 and DAO were found in the HSD-induced Conv mice after supplementary Dubosiella newyorkensis (Fig. 4L, M). Figure 2N illustrates that the blood flow on the intestinal surface was decreased after supplementary Dubosiella newyorkensis in HSD-induced Conv mice. Gut microbiota can also be seen as a key factor in HSD-induced hypertension, Dubosiella newyorkensis could play an effective role in improving blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction.

A The changes in blood pressure (n = 10). B–D The changes in vasoconstriction and vasodilation-related factors, such as NO (B), ET-1 (C), and NO/ET-1 (D). E–G The changes in vascular endothelial active factors, such as EMPs (E), VEGF (F), and Ang1 (G). H–K The changes in immunity and inflammation-related factors, such as TNF-α (H), IL-1β (I), IL-6 (J), and sIgA (K). L–N The changes in the intestinal vascular barrier, such as NHE3 (L), DAO (M), and intestinal perfusion (N). The intestinal perfusion in the four groups (n = 3) was evaluated with laser speckle flowmetry, with red indicating high perfusion and high flux and blue indicating low perfusion and low flux. HS high-salt diet group, HS+Dubo high-salt diet with supplementary NYU-BL-A4 group, NO nitric oxide, ET-1 endothelin-1, EMPs endothelial microparticles, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, AngI angiotensin I, IL-1β interleukin-1β, IL-6 interleukin-6, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α, sIgA secretory immunoglobulin A, DAO diamine oxidase, NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger type 3. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; ns, no statistical significance; n = 6–7.

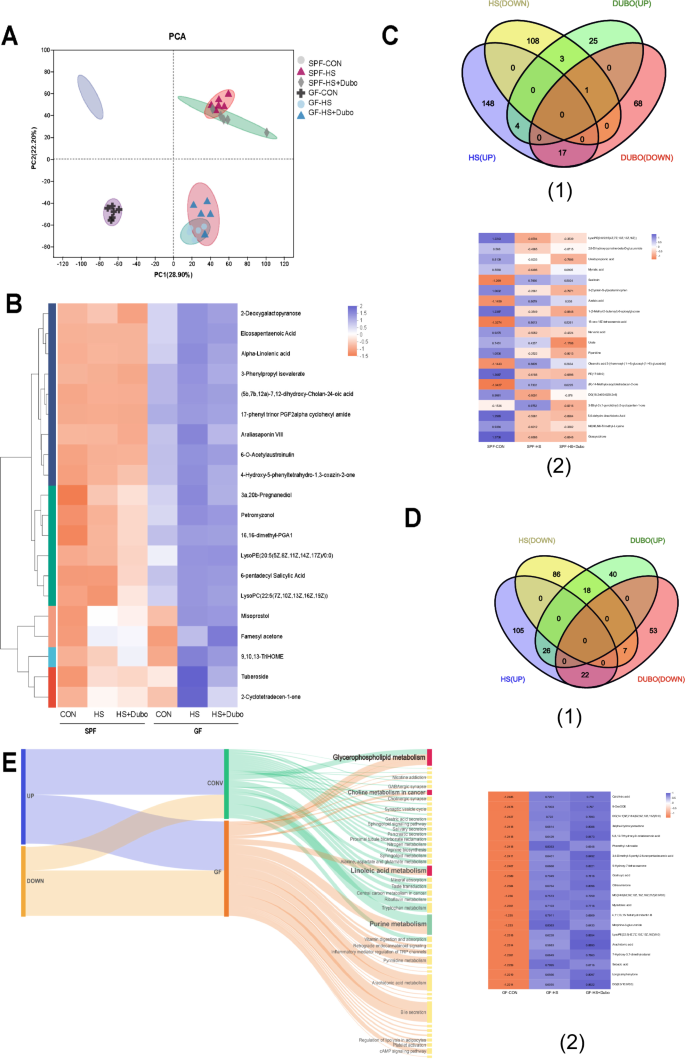

Pentosidine, production inhibited by Dubosiella newyorkensis, increases blood pressure in mice

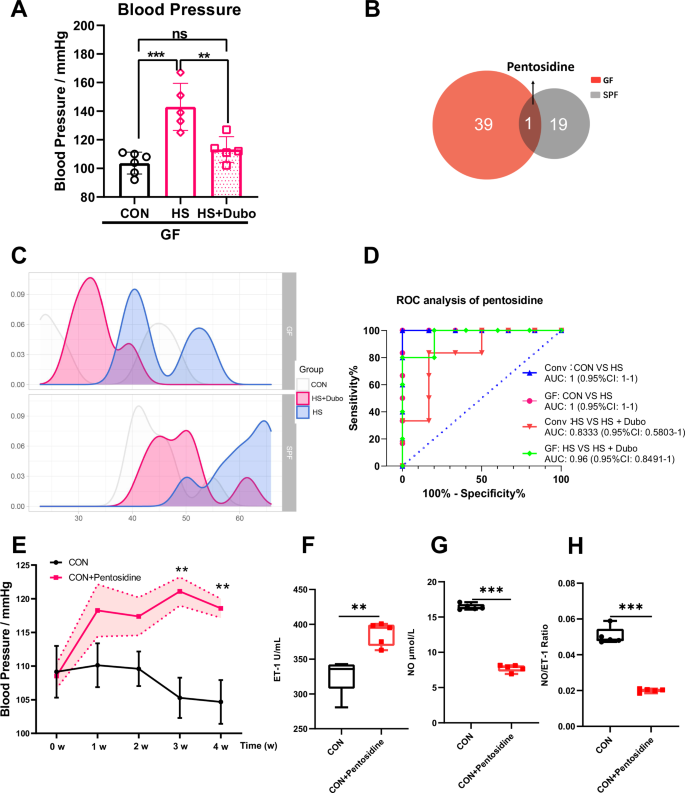

To verify the role of NYU-BL-A4 in HSD-induced hypertension, the animal experiment was repeated using GF mice. As shown in Fig. 5A, the blood pressure of GF mice was found to significantly increase after 4 weeks, while Dubosiella newyorkensis could inhibit the increased blood pressure after 4 weeks, the same as Conv mice. Untargeted metabonomics was carried out to investigate the serum metabolites after Dubosiella newyorkensis treated HSD-induced Conv and GF mice. Figure 6 illustrates the metabonomics analyses of Dubosiella newyorkensis in response to HSD in Conv and GF mice. The PCA clustering of metabolites between HSD intervention mice (HS) and normal diet mice (Non-HS) showed significant left-right separation both in Conv (SPF) mice and GF mice in Fig. 6A. In the right quadrant (mice with HSD), the intervention effect of Dubosiella newyorkensis on metabolites in mice is significant, which is manifested in the obvious separation of metabolite clustering (Fig. 6). A similar separation was observed in the metabolic profiling heatmap (Fig. 6). The Venn diagram shows that NYU-BL-A4 affected 120 differential metabolites in Conv mice with HSD, including 32 upregulated and 88 downregulated metabolites (Fig. 6C1, Supplementary Table 6). The metabolites affected by the HSD and Dubosiella newyorkensis intervention were combined, and 20 differential metabolites were found in Conv mice (Fig. 6C2). Meanwhile, there were 167 different metabolites in GF mice induced by HSD after co-intervention with Dubosiella newyorkensis, with 85 upregulated metabolites and 82 downregulated differential metabolites (Fig. 5D1, Supplementary Table 7). Following the same metabolite analysis steps as the Conv mice, 40 differential metabolites were identified in GF mice (Fig. 6D2). The metabolic pathways of the upregulated and downregulated metabolites were enriched. The HSD-induced differential metabolites in Conv and GF mice upregulated by Dubosiella newyorkensis were co-enriched in the pathways of glycerophospholipid metabolism, choline metabolism in cancer, and linoleic acid metabolism. In contrast, the downregulated metabolites were co-enriched in purine metabolism (Fig. 6E). Therefore, Dubosiella newyorkensis regulates the blood pressure of Conv and GF mice by upregulating glycerophospholipid metabolism, choline metabolism in cancer, and linoleic acid metabolism while downregulating purine metabolism.

A The changes in blood pressure of GF mice. B, C The common serum metabolite was screened using the Venn diagram and density curve. D ROC analysis of pentosidine in HSD-induced Conv and GF mice with supplementary NYU-BL-A4. E The changes in blood pressure with supplementary pentosidine. F, G, H The changes in vasoconstriction and vasodilation-related factors, such as NO, ET-1, and NO/ET-1. CON control group, HS high-salt diet group, HS+Dubo high-salt diet with supplementary NYU-BL-A4 group, CON+Pentosidine supplementary pentosidine group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA was used for multi-group comparison, and t-test was used for the two groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; ns, no statistical significance; n = 5–6.

A The PCA plot. B The heatmap of metabolites in Conv and GF mice. C1 The Venn diagram in Conv mice. C2 The heatmap of differential metabolites in Conv mice. D1 The Venn diagram in GF mice. D2 The heatmap of differential metabolites in GF mice. E Dubosiella newyorkensis (NYU-BL-A4) altered the common serum metabolic pathway in conventional (Conv) and germ-free (GF) mice fed a high-salt diet, and in the shared pathways, the upregulated pathways are marked in green and the downregulated pathways in red. HS high-salt diet, Dubo/DUBO, Dubosiella newyorkensis (NYU-BL-A4).

Pentosidine was the only common differential metabolite among the differential metabolites in Conv and GF mice (Fig. 5B). ELISA was performed to quantify the changes in serum pentosidine in Conv and GF mice. The density curve revealed changes in pentosidine in all groups, suggesting a rightward shift after HSD but a leftward shift after Dubosiella newyorkensis supplementation (Fig. 5C). These findings indicate that pentosidine might be a biomarker in mice with HSD and act as a target of Dubosiella newyorkensis. In addition, ROC analysis and quantitative analysis were conducted to confirm the significance of the relationship between pentosidine, HSD, and Dubosiella newyorkensis in Conv and GF mice. The area under the curve (AUC) was 1 (0.95% CI: 1–1) in Conv and GF mice induced with or without an HSD. In HSD with NYU-BL-A4 supplementation in Conv and GF mice, the AUC was 0.8333 (0.95% CI: 0.5803–1) and 0.96 (0.95% CI: 0.8491–1), respectively (Fig. 5D). Dubosiella newyorkensis effectively inhibited pentosidine in HSD-induced Conv and GF mice. The findings showed that HSD increased the serum metabolite pentosidine in Conv and GF mice, which was alleviated by Dubosiella newyorkensis. The experiment was repeated in GF mice and yielded consistent results, showing that Dubosiella newyorkensis alleviated serum metabolite pentosidine in HSD-induced GF mice as well.

The potential functional categories of gut symbiotic Dubosiella newyorkensis were investigated to identify its probiotic characteristics. Gene ontology (GO) showed the detailed biological process, cellular components, and molecular function (Supplementary Fig. 3A). The clusters of orthologous groups of proteins (COGs) showed that Dubosiella newyorkensis is mainly enriched in amino acid transport and metabolism (181 genes) and carbohydrate transport and metabolism (156 genes) (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the ortholog cluster of KEGG annotation showed that Dubosiella newyorkensis is mainly enriched in carbohydrate metabolism (185 genes) and amino acid metabolism (120 genes) (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Together, these findings suggest that Dubosiella newyorkensis is mainly enriched in carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism. The detailed KEGG pathway of carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3D. The gene count distributions of carbohydrate-active enzyme families showed that Dubosiella newyorkensis is mainly enriched in glycoside hydrolases (43.64%), glycosyltransferases (28.05%), carbohydrate esterases (23.17%), and auxiliary activities (2.44%) (Supplementary Fig. 3E). Therefore, Dubosiella newyorkensis may affect enzymatic saccharification. Finally, the pentosidine synthetic pathway related to the bacterial gene was constructed and shown in Supplementary Fig. 2F, indicating that Dubosiella newyorkensis may affect pentosidine synthesis. For further verification, C57BL/6J mice were intraperitoneally injected with the dilute pentosidine solution for 4 weeks. The results indicated that Dubosiella newyorkensis intervention into the metabolite pentosidine could limit vascular endothelial damage. From the third week, a significant increase in blood pressure was observed among the pentosidine-supplemented mice (Fig. 5E). Pentosidine significantly increased ET-1 in pentosidine-supplemented mice and decreased NO and NO/ET-1 (Fig. 5E–G). These data confirm that pentosidine is a specific biomarker in HSD-related hypertension and is inhibited by Dubosiella newyorkensis.

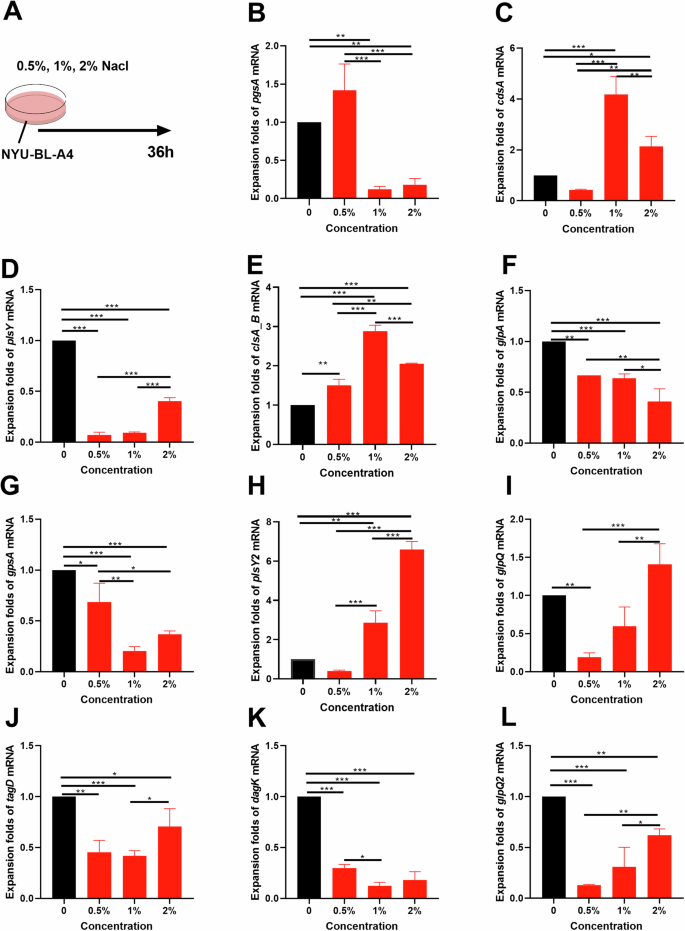

Dubosiella newyorkensis decreases blood pressure by modulating the synthesis of pentosidine in mice

To verify the role of Dubosiella newyorkensis in the development of HSD-induced hypertension to reveal the relationship with the previous metabolism pathways, Nacl was supplemented in vitro bacterial experiment (Fig. 7A). As validation, we selected one of the main metabolic pathways. Eleven differential genes enriched in the screened glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway were observed using RT-qPCR. The result indicated salt has a significant regulatory effect on the 11 genes. Compared to 0.5% salt, excessive salt decreased the mRNA levels of pgsA, gpsA and dagK of Dubosiella newyorkensis, while excessive salt increased the mRNA levels of cdsA, plsY, clsA_B, plsY2, glpQ, tagD and glpQ2 (Fig. 7B–L). Moreover, salt regulated the majority of genes in a concentration-dependent way. All these findings indicate that salt has a potential role in regulating previous metabolism pathways through differential genes enriched in the screened glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway in vitro bacterial experiment.

A Design of bacterial experiments. B–L The relative mRNA levels of the 11 differential genes in the glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; n = 3.

Discussion

As the pathogenesis and prevention of CVDs with vascular endothelial dysfunction are incompletely understood, the relationship between HSD and gut microbiota was investigated to improve scientific knowledge in this area. Multiple recent studies have reported a single strain of bacteria related to CVDs, such as Lactobacillus, Akkermansia muciniphila5, and others still being researched. To investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms of HSD-induced endothelial dysfunction and gut microbiota, Dubosiella newyorkensis, a gut symbiote that is highly responsive to HSD and vascular endothelial injury in mice, was used to intervene in HSD-induced Conv and verified by GF mice. HSD is a key environmental factor in the intestinal microenvironment. In this study, Dubosiella newyorkensis was found to improve vascular endothelial dysfunction and blood pressure induced by HSD. Dubosiella newyorkensis plays a prebiotic role in protecting against vascular endothelial injury, improving immune-inflammatory response, and protecting the intestinal vascular barrier, which depends on the gut microbiota (Fig. 4). Research suggests that Dubosiella newyorkensis is negatively correlated with blood lipid levels and is an important microbe for resisting food-induced obesity and reducing fat mass deposits17,18, and the increased abundance of Dubosiella is accompanied by the remission of diabetes and the effects of aging19. Recent research supports the idea that the administration of angiogenin 4, a vascular endothelial growth factor, increased the presence of Dubosiella20, which provides strong evidence for the correlation between Dubosiella newyorkensis and the vascular endothelium. However, this study somewhat reflects the complexity of Dubosiella newyorkensis’s action, which may be related to the regulation of the gut microbiome’s structure or metabolites, rather than a direct effect. Dubosiella newyorkensis only acts as an intestinal commensal bacterium and a biomarker of vascular endothelial injury in response to the HSD to verify the effect of gut microbiota on HSD. The effects of Dubosiella newyorkensis on blood pressure and vascular endothelial function are relatively independent, but those on vascular endothelial active factors, immune-inflammatory factors, and the intestinal vascular barrier depend on the host’s microbiome. Its medicinal value, efficacy, and pharmacological mechanisms should be studied further.

Vascular endothelial dysfunction is an initial step of macro- and micro-vasculature dysfunctions in CVD patients, and restoring endothelial function is a crucial target as endothelial dysfunction predicts CVD in situations such as coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, and hypertension21,22. A key mechanism underlying CVDs in vascular function is the endothelin (ET) system and endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF; NO)23,24. Other studies have found that HSD increases blood pressure and changes vascular endothelial dysfunction factors in Conv mice, in line with our current research results. Previous research has also suggested that gut microbiome disorder caused by HSD is one of the factors contributing to the pathogenesis of vascular endothelial dysfunction. A series of studies on the blood pressure increase in GF mice caused by the transplantation of fecal microbiota from hypertensive patients or mice induced by HSD directly support the idea that gut microbiota contributes to the pathogenesis of hypertension25,26. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates, for the first time, that GF mice with HSD also developed vascular endothelial dysfunction, such as NO/ET-1 imbalance and high blood pressure, indicating that the gut microbiota is only one of the underlying mechanisms of HSD-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction. Therefore, the gut microbiome cannot be described as a requirement for developing HSD-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction. Consequently, the gut microbiome is essential for vascular physical health. HSD is associated with impaired intestinal mucosal immune function, intestinal inflammation, and intestinal permeability5,14. Furthermore, vascular endothelial dysfunction is associated with increased bowel permeability, increased inflammation, and gut microbiome dysbiosis27,28,29. HSD leads to the production of abnormal metabolites by the gut microbiota and intestinal defense dysfunction. Our study also indicates that the gut microbiota plays an important role in maintaining the host vascular endothelial activating factor and intestinal vascular barrier health, but immune inflammation seems to be a factor induced by HSD independent of the gut microbiota. It means that the gut microbiota promotes the immune-inflammatory response induced by HSD, not by the main inducement. Recent studies have shown that high dietary salt intake is proinflammatory and contributes to chronic inflammatory conditions, in which imbalances in immune homeostasis are critical under the stress that a high-salt environment places on the intestine30. The endothelial active factors, immunity and inflammation-related factors, and intestinal vascular barrier were affected by HSD in Conv mice. Meanwhile, these changes were not observed in mice without gut microbiota. This study confirms the effects of HSD on intestinal mucosal immune function, intestinal inflammation, and intestinal permeability. Even HSD can still cause vascular endothelial dysfunction and the gut commensal bacteria (Dubosiella newyorkensis), in response to HSD, improved blood pressure and the NO/ET-1 balance in both Conv mice and GF mice. Therefore, the gut microbiota adaptively regulates the vascular endothelium dysfunction caused by HSD.

In this study, we integrated and analyzed the metabolic pattern of the HSD in Conv mice and GF mice to further study the adaptive regulation mechanism of the gut microbiota on the high blood pressure induced by HSD. LC-MS/MS metabolomics showed that HSD affected the intestine-liver-blood circulation, mainly by enriching the synthesis of primary bile acids, which are closely related to arachidonic acid. Metabolites are important components of the gut microbiota that are involved in CVD31. In recent years, many metabolites have been discovered, including short-chain fatty acids, trimethylamine oxide, and arachidonic acid, which are observed in HSD-related metabolites and contribute to CVD32,33. These metabolites also reportedly involved in hypertension. A recent clinical metabolomic study found that arachidonic acid metabolism is one of the main metabolic pathways of the ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) produced by primary bile acids to resist cholesterol production34. A recent clinical and preclinical study found that disordered bile acid metabolism can aggravate the damage to vascular endothelial function and morphology in four animal models of bile acid secretion disorders and patients with cholestasis35. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), especially arachidonic acid, modulate the gut microbiota and influence stem cell proliferation and differentiation, contributing to vascular endothelial growth factors36. The importance of arachidonic acid metabolism to the gut microbiota was also confirmed in a study on the mechanism of HSD-induced hypertension in rats6. However, sphingolipid metabolism seems to compensate for the lipid metabolism involving the gut microbiota. The lack of lipid metabolism of the gut microbiota results in the aberrant accumulation of harmful lipid metabolites in tissues. Sphingolipids are particularly impactful among harmful lipid metabolites as they elicit dyslipidemia and, ultimately, cell death that underlies nearly all metabolic disorders37. Therefore, although we found that the gut microbiota can adaptively regulate vascular endothelial function, severe gut microbiome disorder will inevitably increase the incidence of CVD adverse events that are related to hosting metabolic disorders.

In this study, 117 different gut microbe-dependent metabolites were identified in Conv and GF mice. These metabolites could be specific products of HSD metabolism by the gut microbiota. Simultaneously, this research reveals the serum metabolic profile (Supplementary Tables 1, 2) of HSD on Conv and GF mice, laying the groundwork for future research on the gut microbiota involved in salt metabolism in vivo. There were 120 differential metabolites in HSD-induced Conv mice supplemented with Dubosiella newyorkensis and 167 in GF mice. Moreover, this study explores the detailed metabonomics-related mechanisms and serum metabolic profile (Supplementary Tables 3, 4) of HSD-induced Conv and GF mice with supplementary Dubosiella newyorkensis. The differential metabolites in Conv and GF mice may be related to blood pressure. Interestingly, serum pentosidine was downregulated by Dubosiella newyorkensis in HSD-induced mice and was validated as a biomarker by ROC analysis and ELISA analysis. Additionally, the whole-genome sequencing indicated that Dubosiella newyorkensis has inhibitory effects on the synthesis of pentosidine. The potential mechanisms by which the gut microbiota and related metabolites regulate blood pressure are complex. This study confirms pentosidine as a specific biomarker involved in hypertension caused by HSD, which is inhibited by Dubosiella newyorkensis. Non-enzymatic reactions between extracellular proteins and glucose result in advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Pentosidine is a very sensitive marker for all AGEs, and it forms during normal aging but noticeably accelerates with the progression of chronic disease38. It is thought that increased serum pentosidine retention and formation contribute to CVD39. Pentosidine levels may be used as a biomarker for microvascular complications in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), acute ischemic stroke, and type-2 diabetes, among others39,40,41. Interestingly, the serum levels of pentosidine can be used as a diagnostic metabolic marker42,43. A study found that serum pentosidine levels were significantly higher in hypertensive patients and CAD patients compared to healthy elderly individuals43. At the molecular level, pentosidine was found to promote oxidative stress and endothelial cell dysfunction to indicate microvascular complications according to previous studies44,45. In this study, we confirmed that pentosidine is a specific biomarker in HSD-induced Conv and GF mice. Because of the shortage of GF mice during COVID-19 and the difficulty in carrying out, we only conducted validation in conv mice. Further verification in pentosidine-supplemented mice still revealed that pentosidine increased blood pressure in response to HSD in Conv mice. Moreover, genome sequencing of the gut symbiote Dubosiella newyorkensis was conducted, indicating that Dubosiella newyorkensis may inhibit pentosidine synthesis in HSD-induced mice. In addition, salt has a potential role in regulating previous metabolism pathways through differential genes enriched in the screened glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway in vitro bacterial experiment. The metabolism pathways may be the connecting bridge between pentosidine and Dubosiella newyorkensis. All these indicate that salt intake has profound effects on blood pressure by reducing the salt-sensitive gut bacteria, which provides new insight into HSD and gut microbiota in the development of hypertension in mice.

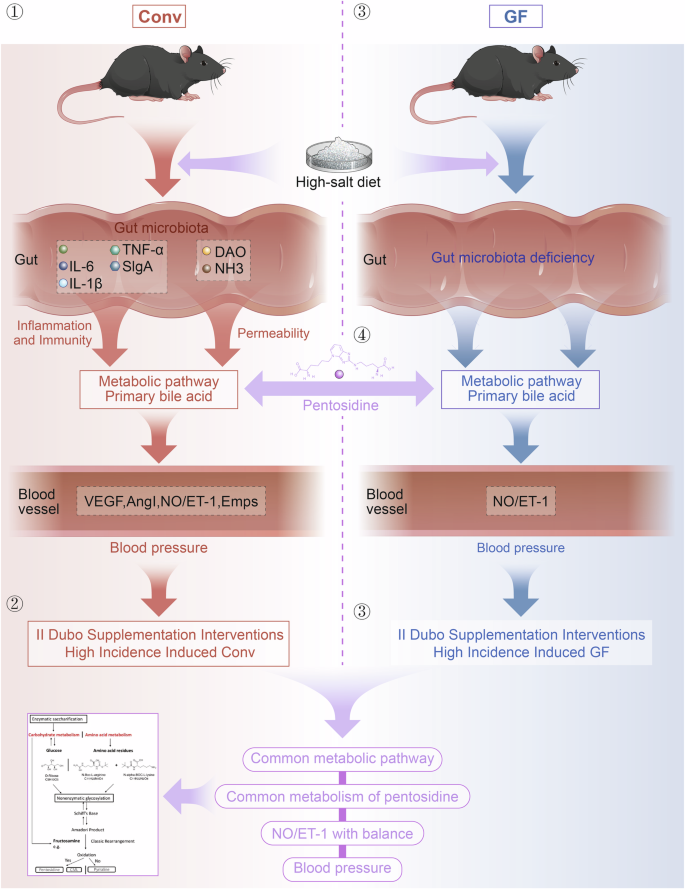

Currently, it is customary to study the pathogenesis and prevention of HSD-induced hypertension from gut microbiota, despite the complexity of the pathogenesis of hypertension and prevention. The pathogenetic role of intestinal bacteria in HSD-induced mice is extremely complex, and the gut barrier is critical for this interaction. This study describes the gut microbiota as a new way to regulate blood pressure in HSD-induced Conv and GF mice. Factually, HSD prominently reduced the abundance of Dubosiella newyorkensis and increased the level of the metabolite pentosidine in the serum, thereby regulating the balance of NO and ET-1, leading to endothelial dysfunction (Fig. 8). Our study indicates pentosidine may be not only a biomarker of HSD but also a target of Dubosiella newyorkensis in the development of HSD-related hypertension. The study provides a new target to resist HSD-related hypertension.

① HSD-induced increased blood pressure in conventional (Conv) mice and the gut symbiotic bacteria Dubosiella newyorkensis (NYU-BL-A4) was screened; ② Dubosiella newyorkensis (NYU-BL-A4) played an important role in HSD-induced mice; ③ The potential mechanism of action has been explored; ④ The primary metabolic route and important metabolites have been verified in vivo animal research and in vitro bacterial experiments. Dubo Dubosiella newyorkensis (NYU-BL-A4), NO nitric oxide, ET-1 endothelin-1, EMPs endothelial microparticles, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, AngI angiotensin I, IL-1β interleukin-1β, IL-6 interleukin-6, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α, sIgA secretory immunoglobulin A, DAO diamine oxidase, NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger type 3, Conv conventional, GF germ-free.

Methods

Preparation of animals and bacteria

All mice used in this study were C57BL/6J background. A total of 30 SPF mice and 18 GF mice (male, aged 6–8 weeks) were separately provided by Beijing huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and the Animal Experiment Oonaseptic animal research platform of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. All mice were kept in consistent environments at a temperature of 20–24 °C, 50% humidity, and an isochronous day/night cycle with day from 07:00–19:00 and night from 19:00–07:00. Animal experiments were approved and performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the animal experiment ethics committee of Jinan University and the animal experiment ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (the ethics numbers: IACUC-20200923-09 and 2021503-1). All procedures conformed to the guidelines from Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Isoflurane was used for euthanasia to avoid suffering given through a small animal ventilator.

The International Preservation Center provided Dubosiella newyorkensis (NYU-BL-A4, ATCC: TSD-64) to the Guangdong Institute of Microbiology, which cultivated and supplied it to us to ensure the quality of the strains. The lyophilized bacterial powder was dissolved in 0. 2–0. 3 ml of anaerobic sterile water and spread on a flat medium for anaerobic culture at 37 °C for 2–3 d in an anaerobic workstation. After the colony was visible on the plate, it was washed with anaerobic sterile water to remove the bacteria, subcultured into the liquid medium according to an inoculation ratio of 1:5, and the bacterial solution was transferred to the biochemical incubator at 37 °C for 48 h. The medium preparation is detailed in the Supplementary Material.

Animal grouping, design, and intervention

The conventional (Conv) mice were divided into three groups: the control group (CON), the HSD group (HS), and the HSD with supplementary NYU-BL-A4 group (HS+Dubo), each with 10 mice. Likewise, the GF mice were divided into the same groups as the Conv mice, with 6 mice in each group. In addition, 20 SPF C57BL/6J mice were randomly divided into a control group (CON) and a supplementary pentosidine group (CON+pentosidine).

All of the mice were given free access to food. The mice in the high-salt group were fed an 8% NaCl diet for 4 weeks, while the control group was fed a normal diet. The ingredients for the 8% NaCl diet are presented in Supplementary Material1. The NYU-BL-A4 bacterial solution was made into a 100 μl 108 (CFUs) /100 μl for 4 weeks, while the control group received the same amount of normal saline. The same dose of the NYU-BL-A4 bacterial solution was given to the GF mice once. To assess NYU-BL-A4 colonization in GF mice, feces were collected daily for 7 d after treatment and NYU-BL-A4 colonization was affirmed by Gram staining.

Screening of high-salt responsive symbiotic gut bacteria

The mice were used to screen for the high-salt responsive gut bacteria associated with endothelial dysfunction. Fecal samples were collected from Conv mice after 4 weeks of an HSD. The bacterial 16S rRNA gene was extracted from fecal samples, and its V3–V4 hypervariable regions were amplified and subjected to paired-end sequencing (2 × 300) on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). The 16S sequencing data was obtained from the NCBI SRA (Accession number: PRJNA660089), as well as the annotated genus information. Brain-heart infusions (BHI) of 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0%, 4.0%, and 8.0% NaCl medium, respectively, were used to culture the screened high-salt responsive bacteria (NYU-BL-A4) in anaerobic bottles. The cultural environment was kept at 37 °C for 30 min and 180 r/min. The bacterial culture medium was extracted at 0 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 50 h, respectively, and the OD was measured at a wavelength of 600 nm with a full wavelength reading microplate reader (Multiskan GO, Thermo Fisher, GER).

Clinical sample and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Fecal samples were obtained from 12 patients with high blood pressure and 12 healthy controls at the Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University (Wuxi, Jiangsu, China; Supplementary Material2). The fecal samples were gathered with informed consent according to the Institutional Review Board of Ethical Committee-approved protocol and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The collected fecal samples were prepared into bacterial solution, fixed at 4 °C for 24 h, and then prepared for smear experiments. In order to have enough bacteria extracted, fecal samples from two patients were mixed in equal amounts to form one sample. The slices were dripped with DAPI staining solution for re staining. Finally, the slices were observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope and images were collected. All bacteria show orange-red fluorescence signal, while Dubosiella shows a yellow fluorescence signal.

Blood pressure measurement

Due to the risk of jeopardizing the GF mice’s incomplete holobiont status, the preferred radiotelemetry method for monitoring rodent blood pressure was abandoned in this study46. As in our previous method13, Conv mice’s blood pressure was measured in weeks 0, 2, and 4 using a mouse tail non-invasive sphygmomanometer (Visitech Systems, BP-2000-M). To avoid polluting the sterile environment, the blood pressure of GF mice was measured in the fourth week, and all operations were performed on the sterile operation platform.

Intestinal surface microblood flow scan

Three mice from each group of Conv mice were randomly selected for intestinal perfusion testing. Isoflurane with 3% concentration was given through a small animal ventilator to anesthetize the animals for 1 min. After laparotomy, the blood flow across the intestinal surface was observed using the moorFLPI-2 blood flow imager (Moor Instruments, UK)47. There were approximately 20 cm between the scan head and the intestinal surface. One frame per second was set as the image acquisition rate with the normal resolution mode, and the blood flow was recorded for 25 s.

Blood and intestinal tissue collection

At the end of the study, isoflurane with 3% concentration was given through a small animal ventilator to anesthetize the animals. Blood was obtained from the eyeball, centrifuged, and the serum was stored for testing. Intestinal tissues were obtained from the small intestine, washed with normal saline, and stored for testing.

Quantitative detection of intestinal and vascular injury factors

The stored serum was used to test for nitric oxide (NO), endothelin-1 (ET-1), endothelial microparticles (EMPs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiotensin I (AngI) to estimate the function of vascular endothelial cells quantitatively through ELISA; The intestinal tissues were used to test for tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) to estimate intestinal inflammation, secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) for intestinal mucosal immune function, diamine oxidase (DAO) for intestinal permeability, and Na+/H+ exchanger type 3 (NHE3) for the intestinal absorption of salt. The ELISA kits were purchased from MEIMIAN (Yancheng, China).

Medium preparation

Solution A: 10 g pork and beef granules were ground and boiled with 500 ml distilled water for 20 min. Then the meat residue was filtered with four layers of gauze and supplemented with 500 ml of water for standby.

Solution B: casein peptone 10.0 g, yeast extract 5.0 g, K2HPO4 5.0 g, azurol solution (0.1% w/V) 0.5 ml, anhydrous glucose 4.0 g, cellobiose 1.0 g, maltose 1.0 g, soluble starch 1.0 g, cysteine hydrochloride 0.5 g, dissolved in 480 ml distilled water. Then, 10 ml of hemin solution and 10 ml of vitamin K1 solution were filtered and added after sterilization.

Hemin solution: dissolve 50 mg hemin in 1ml 1n sodium hydroxide solution and make up 100 ml with sterile water. Keep away from light at 4 °C.

Vitamin K1 solution: Add 20 ml of vitamin K1 solution into 20 ml of 95% ethanol and mix well. Keep away from light at 4 °C.

The solution A and B were mixed well and adjusted pH to 7. If solid medium is prepared, 2% agar powder shall be added. 121 °C 20 min high-pressure steam sterilization, ready for use.

The liquid culture medium shall be subpacked into an anaerobic bottle, boiled in a water bath in advance to drive away the dissolved oxygen in the liquid, filled with nitrogen for about 10 min, and then quickly added with rubber plug and gland, and sterilized with high-pressure steam at 121 °C for 20 min. After the solid medium is sterilized by high-pressure steam, the flat medium is made in the biosafety cabinet and transferred to the anaerobic workstation after solidification.

Gram staining

Under the aseptic operation conditions, a small number of samples were picked up with an inoculation ring, evenly coated on a clean slide, and heated on a flame to kill the bacteria and make them adhere and fix. The cover glass was then stained with ammonium oxalate crystal violet for 1 min and washed with tap water to remove the floating color. The cover glass was then mordanted with iodine potassium iodide solution for 1 min, and the excess solution was poured out. The cover glass was then decolorized with a neutral decolorizing agent such as ethanol (95%) or pyruvic acid for 30 s, the Gram-positive bacteria were not faded but turned purple, and the gram-negative bacteria were faded and turned colorless. When the cover glass was counterstained with saffron or sand yellow for 30 s, the gram-positive bacteria were still purple and the Gram-negative bacteria were red.

Serum metabolomics

UPLC-MS/MS analysis was conducted on the serum. The metabolites of every 6 samples were extracted, and quality control samples were prepared. The metabolites were then separated by chromatography using an ExionLCTMAD system (AB Sciex, USA) and ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 µm; Waters, Milford, USA). After the UPLC-TOF/MS analyses, the raw data were imported into Progenesis QI 2.3 (Nonlinear Dynamics, Waters, USA) for peak detection and alignment. VIP values greater than 1 and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Subsequently, a differential metabolite analysis was performed on the Majorbio Cloud Platform (https://cloud.majorbio.com). These methods are shown in detail in the Supplementary Material.

Genome sequencing of Dubosiella newyorkensis

The genomic DNA was extracted using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega) and sequenced with the PacBio RS II Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) and Illumina sequencing platforms. These processes were conducted according to the manufacturers’ instructions, and the resulting data were used for Bioinformatics analysis. Furthermore, all analyses (assembly, gene prediction, and annotation) were performed on the free Majorbio Cloud Platform. The PacBio and Illumina reads were then used to assemble the entire genome sequence.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis of Dubosiella newyorkensis

Bacterial quilt 1xPBS (pH = 7.2) was gently mixed, and the bacteria were fixed on the carrier net by 2% phosphotungstic acid negative staining method. After being dried by air, the microstructure of the bacteria was observed by transmission electron microscope (TEM).

Pentosidine intraperitoneal injection intervention

Pentosidine (15 mg) lyophilized powder was mixed with 280 μl PBS to prepare the stock solution. Each mouse was intraperitoneally injected with 0.2 ml of diluent pentosidine at a dose of 2 mg/Kg/d for 4 weeks.

Bioinformatics analysis

The bacterial 16S rRNA derived from the fecal samples of the Conv mice via paired-end sequencing were spliced into a sequence, and the target sequence was filtered for quality control. The filtered sequence was compared with the NCBI database and annotated genus information. The strategies of the high-salt responsive gut symbiotic bacteria screening and bioinformatics analysis were as follows: (1) The abundance Circos map was used to analyze the proportion of the dominant bacterial genus in each group (such as the control group and the HSD group) and the data analyses were conducted on the free Majorbio Cloud Platform; (2) LDA Effect Size (LEfSe) analysis was used to label the high-salt responsive genus bacteria (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy); (3) Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to calculate the correlation coefficient between the abundance of bacteria by genus and vascular endothelial factors to screen for key response bacteria. The R v3.1.3 was used to perform this analysis and the heatmap was exported with the “pheatmap” package of R v3.1.3 to reveal the synergy of bacteria by genus.

The UPLC-MS/MS metabolomics data were scaled via autoscaling, mean centering, and scaling to unit variance (UV), and then subjected to a multivariate statistical analysis of partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) for 7-fold cross-validation. KEGG compounds were classified according to the level of biological function that the metabolites were involved in. The dataset was scaled with the “pheatmap” package in R v3.3.2 to export the hierarchical cluster diagram of the relative quantitative values of metabolites. The methods are shown in detail in the Supplementary Material. The metabolic pattern of gut microbiota was based on the UPLC-MS/MS metabonomics KEGG enrichment and topology analysis. The metabolic set was enriched in the KEGG pathway. The hypergeometric distribution algorithm Relative-betweenness Centrality obtains the topology pathway of the metabolites in the metabolic set. The p-value was corrected with the BH method (FDR < 0.05), and significant enrichment was found in the pathway. The pathway enrichment and topology analyses were conducted on the free Majorbio Cloud Platform. Furthermore, using the KEGG pathway maps for metabolic pathways on GenomeNet (https://www.genome.jp/), the differential metabolites (p < 0.05) were mapped to the KEGG pathway with FDR < 0.05. The transformation process of compound metabolism in vivo was analyzed via differential metabolites’ compound KO annotation integration. The metabolites mapped to the KEGG pathway on Conv mice are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The metabolites mapped to the KEGG pathway on GF mice are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

PrimeScriptTM RT Master Mix (RR036A, Takara, Kyoto, Japan) was used to reverse-transcribe total RNA from NYU-BL-A4 into cDNA after it had been extracted using TRIzol in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. With the CFX ConnectTM Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) and Absolute Q-PCR SYBR Green Supermix (172-5124, Bio-Rad, Irvine, CA, USA), primers (Supplementary Table) were utilized for RT-qPCR.

Statistical analyses

The continuous data conform to the normal distribution and were expressed as the mean ± SEM. If the variance was homogeneous, one-way ANOVA was used for multi-group comparison, and the LSD test was used for multi-group pairwise comparison. If the variance was not homogeneous, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. The difference between the two groups was measured with an independent samples t-test with an inspection level of α = 0.05 and p < 0.05 indicating a significant difference. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0.

Responses