Hypothalamic neuronal-glial crosstalk in metabolic disease

Introduction

Obesity is currently the largest growing global epidemic1 and is a leading risk factor for type 2 diabetes (T2D)2,3, cardiovascular disease3,4,5, liver disease6,7, hypertension2,3,5,8, stroke5,9,10 and cancer11,12. By 2035, it is predicted that there will be more people worldwide living with obesity than without13. Obesity, therefore, presents itself as a leading global health burden. Beyond the pathophysiological consequences of obesity and its co-morbidities, the obesity burden imparts immense strain on the economy and world healthcare system. In 2020 alone, the cost of treating obesity-related disorders alone exceeded >$1.96 trillion (USD)13. The exponential growth in incidence and clinical burden coupled with the unsustainable economic burden places the discovery of effective therapeutics for the treatment of obesity as a leading global health challenge.

How did we get to this point? The aetiology of obesity is complex, and the contributing factors are poorly understood. The average daily caloric intake in the United States has increased by 18% from 3400 to 4000 kilocalories (kcal) between 1909 and 201914, which far exceeds the average total daily energy expenditure for a non-obese adult (~2400 kcal/day)15. Diet composition has also varied over time, and with the growing prevalence of processed foods, the availability and consumption of dietary fats has been steadily increasing14. These dietary changes are further compounded by a shift towards a more sedentary life- and workstyle, factors that were further inflated by stay-at-home orders during the COVID-19 pandemic16. In the simplest sense, obesity arises due to disparities in energy balance, whereby energy intake exceeds energy expended by the body. As such, for weight loss to occur in obesity, energy intake must be surpassed by energy expenditure, through either dietary restriction and/or increased exercise. Whilst inherently simplistic, clinical interventions have resoundingly failed capacity to promote the remission of obesity over the long term, with most patients regaining the majority of lost weight, irrespective of the rate at which that weight is lost17,18. This reductive clinical perspective discounts the vast complexities of how the body coordinates, defends and alters metabolism, which goes well beyond simply energy in vs. out.

There is a well-established functional connection between the brain and the body in the orchestration of whole-body metabolism. Hormones produced in peripheral tissues are released into the circulation in response to metabolic cues, where they travel into the central nervous system (CNS) to regulate cellular circuitry governing energy balance. The majority of current literature in this field focuses on the action of these hormones on neurons within the brain, with particular focus on subsets of neurons within a brain region called the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC)19,20. In addition to the neuronal correlates of metabolism, it is becoming clear that non-neuronal cells of the CNS, known as glia, are functionally integrated into the physiological regulation of metabolism and the pathogenesis of metabolic disease.

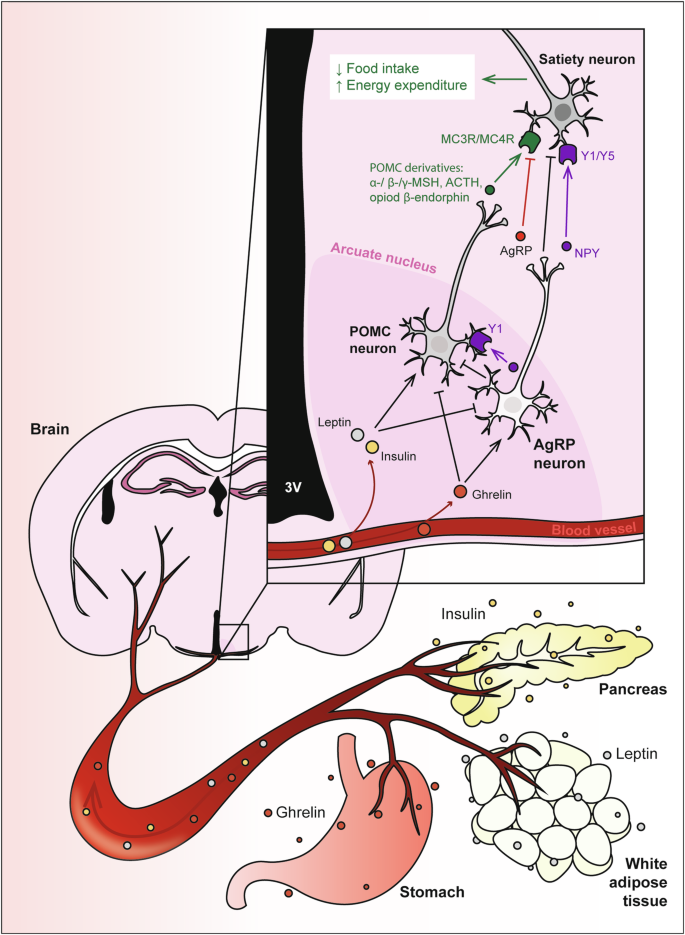

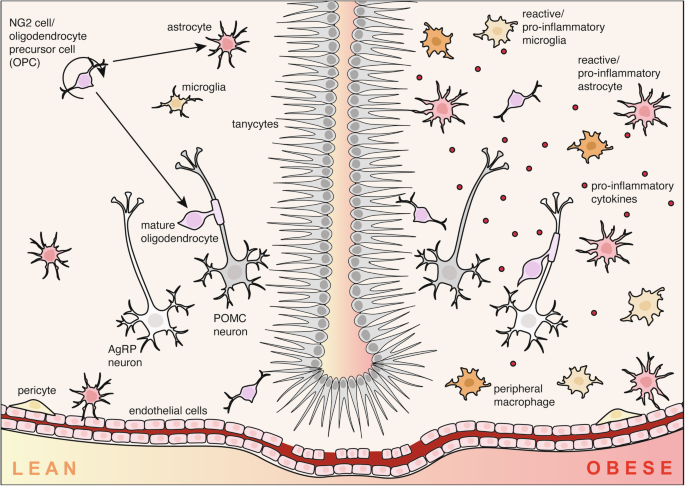

In this review, we will summarise the neuroendocrine axis of the ARC, focusing on key metabolic hormones and how they regulate whole-body metabolism (Fig. 1). We will explore the evidence supporting the roles of both neurons and various glial cells in driving metabolic disease (Fig. 2). We finally argue that glial cells possess untapped potential as regulators of the hypothalamic microenvironment and are therefore significant candidates for therapeutic targeting in the treatment of metabolic disease.

Hormones released from the stomach (ghrelin), white adipose tissue (leptin) and pancreas (insulin) are released into the bloodstream and circulate to the brain to activate proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. Activation of these neurons regulates food intake, energy expenditure and glucose metabolism. Insulin and leptin have anorexigenic effects by inhibiting AgRP neurons and activating POMC neurons, to promote secretion of POMC-derived melanocortins, which then bind to MC3R/MC4R on secondary neurons to reduce food intake and increase energy expenditure. Conversely, orexigenic ghrelin inhibits POMC neurons, and activates AgRP neurons to secrete appetite-stimulating peptides including AgRP, a MC3R/MC4R antagonist. AgRP neurons also release the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and neuropeptide Y (NPY), which binds to Y1 and Y5 receptors, to inhibit POMC neurons and downstream satiety neurons.

In the hypothalamus of lean mice (left), glial cells including astrocytes, microglia, nerve-glial antigen 2 (NG2)/oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), pericytes and tanycytes facilitate healthy physiological function by regulating metabolic hormone transport and neuronal function. In contrast, the obese brain is characterised by hypothalamic inflammation, driven by a phenomenon called reactive gliosis. Hypothalamic astrocytes and microglia proliferate and adopt pro-inflammatory phenotypes which can lead to dysfunction of agouti-related peptide (AgRP) and proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons.

The neuroendocrine axis of metabolism

The regulation of appetite involves a complex neuroendocrine axis, where key signalling hormones, such as insulin, leptin, and ghrelin play pivotal roles. Originating from peripheral tissues, these hormones are synthesised and released into the bloodstream, exerting their effects on various tissues, notably the brain, to modulate hunger, satiety, whole body metabolism and glycaemic control (Fig. 1).

Ghrelin is an appetite-stimulating hormone predominantly produced by X/A-like cells of the oxyntic gland in the stomach in response to fasting21. Secreted ghrelin travels via the bloodstream to signal to the brain via the ghrelin receptor, also known as growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR), to stimulate feeding behaviour22,23. Peripheral administration of ghrelin significantly increases food intake in both lean mice24, and humans25.

Leptin is a satiety-stimulating hormone produced by adipocytes in white adipose tissue26, encoded by the Ob gene27,28. One of the major transgenic mouse models of obesity is the ob/ob model, in which mice homozygous for a mutation in the leptin gene are severely obese, hyperglycaemic and hyperlipidemic29. The ob/ob model is largely phenocopied by db/db mice, which have a mutation in the leptin receptor gene29,30. Systemic leptin injection promotes satiety, resulting in decreased food intake and body weight in lean mice27 and humans31.

Insulin was first identified from pancreas extract, and was found to lower blood sugar in dogs32. Produced by β-cells in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas, this hormone is released postprandially in response to rises in blood glucose. Insulin signalling is necessary for life. Insulin-deficient mice are viable at birth, but are runted compared to wildtype controls and quickly develop diabetes and die within 48 hours33.

Efficient signalling of metabolic hormones in the brain is necessary for the body to appropriately respond to changing energy needs throughout the day and lifetime. When these chronic imbalances occur, metabolic disease can arise. Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is caused by autoimmune responses against pancreatic β-cells, causing insulin deficiency and hypoinsulinaemia34. Conversely, T2D arises not due to a lack of insulin secretion, but rather, the inability of insulin to efficiently signal to maintain glucose homoeostasis. This phenomenon is termed insulin resistance. Functional insulin resistance can be simulated in a laboratory setting by genetically deleting the insulin receptor, preventing the activation of downstream pathways. At birth, insulin receptor knockout mice are indistinguishable from their littermate controls35, however, once they commence feeding, they shortly develop hyperglycaemia and hyperketonaemia, indicating impaired fuel metabolism36, similar to insulin-deficient mice33. Like ligand-deficient animals, insulin receptor-deficient mice will also die within the first few days of life from these complications35,36.

Insulin resistance occurs not only in peripheral tissues but also the brain37. Insulin signalling in the brain initiates glucose uptake in peripheral tissues such as adipose tissue and skeletal muscle cells, as well as decreased glucose production in the liver38. Neuron-specific deletion of the insulin receptor, in essence, producing neuronal insulin resistance, results in marked obesity, featuring hyperinsulinaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia39, demonstrating that disrupted insulin signalling to the brain is a key driver of metabolic disease. For a more detailed review of insulin signalling in the brain, see40. In addition to insulin resistance, the obese brain also presents with both leptin41,42,43 and ghrelin resistance24. Neuronal deletion of the leptin receptor results in obesity and hyperglycaemia44. Functionally, leptin resistance prevents satiety, causing mice to overconsume calories compared to controls41. In obesity, leptin receptor-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation is reduced, despite high fasting serum leptin levels41. Human clinical studies have found that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leptin levels are also positively correlated with BMI, but the ability of leptin to be taken up into the CSF from the blood is reduced in obesity45,46. This impaired transport has been observed prior to central leptin resistance in animals47 A similar phenomenon occurs for ghrelin signalling, where despite effectiveness in lean mice, peripheral administration of ghrelin fails to increase food intake in obese mice24. Metabolic hormone resistance, particularly in the brain, is, therefore, a key driver of disease, and occurs in the ARC.

The arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC) and its key neuronal subpopulations

The ARC is a subregion of the hypothalamus involved in coordinating feeding behaviour and energy expenditure. Metabolically relevant neuronal correlates within the ARC develop during the first two postnatal weeks, during which neurons form projections to secondary regions including the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMH), paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH), medial preoptic nucleus (MPN), lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) and anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV)48,49,50.

Neuronal subpopulations in the ARC consolidate hormonal, neuronal and nutrient signals from the periphery to regulate energy balance and glucose homoeostasis via the melanocortin system. The melanocortin hormones include: α-, β- and γ-melanocyte stimulating hormones (α-, β- and γ-MSH), adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH) and β-endorphin), which are all derived from the precursor pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC)51. Upon cleavage and secretion, melanocortins from POMC neurons in the ARC bind to melanocortin 3 and 4 receptors (MC3R and MC4R, respectively) on downstream signalling neurons in the PVH to induce satiety52. As such, agonists against MC3R and MC4R can significantly reduce feeding53. POMC signalling is indispensable for satiety, as POMC-null mice develop pronounced obesity54. Similarly, genetic deletion of MC4R also results in obesity, hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycaemia55. Deletion of MC3R has less profound effects, with minor weight gain and no changes in food intake, serum insulin or blood glucose levels56. Rather, they display reduced activity and ability to oxidise fatty acids when placed on a high fat diet56, suggesting that MC4 binding has stronger implications on whole body metabolism than MC3. In humans, gain-of-function mutations in the MC4R gene are protective against obesity, whereas people with loss-of function-variants have a higher propensity for high BMI, T2D and coronary heart disease57

POMC neuron activity is modulated by hormonal cues. Leptin activates POMC neurons58, stimulating satiety by simultaneously depolarising the POMC neurons and reducing GABA-mediated inhibitory post-synaptic currents59. Although mice that have the leptin receptor conditionally deleted from POMC neurons display significantly higher body weight and adiposity60, surprisingly, leptin-mediated POMC signalling has not been shown to regulate food intake60,61. Rather, it appears that leptin regulates body weight though POMC neurons by suppressing hepatic glucose production61 and potentially by increasing energy expenditure, although the latter point has not been consistently shown60,61. Intracerebroventricular (ICV) insulin infusion does not produce robust effects on food intake or body weight62,63. However, combined leptin and insulin infusion into the ARC promotes synergistic actions on adipose tissue thermogenesis, increasing energy expenditure to promote weight loss and improved glycaemic control63.

The downstream efferent connections of POMC neurons are functionally opposed by a subpopulation of neurons expressing agouti-related peptide (AgRP). AgRP and POMC neurons hold combatant actions on feeding behaviour, whereby AgRP neurons are considered orexigenic (appetite-stimulating), in contrast to anorexigenic (satiety-stimulating) POMC neurons. AgRP neurons regulate food intake by inhibiting electrophysiological signalling in POMC neurons64, therefore inducing hunger. They do this by releasing neuropeptides AgRP and neuropeptide Y (NPY), as well as the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)59,65. AgRP is a potent MC3R/MC4R antagonist66, inhibiting the satiety-inducing action of POMC neurons by competing with the MC3/MC4 receptors. Instead of competing with the melanocortins, NPY binds to cognate receptors NPY receptors 1-6 (Y1-6) to induce hunger, such that NPY-infusion into the brain induces a dose-dependent feeding response67. NPY and its receptors are widely expressed in the body, but it is Y168 and Y569,70 that have been associated with food intake regulation. Pharmacological antagonism of the Y1 receptor dampens NPY-induced feeding68. Furthermore, inhibition of the Y5 receptor via antisense oligodeoxynucleotides significantly decreases food intake70. Both Y1 and Y5 are expressed in the PVH, where POMC neuron projections are located, as well as the ARC71. Somewhat counterintuitively, ghrelin-stimulated AgRP neuron signalling is quickly inhibited upon sensory detection of food72, and it is the release of NPY that is necessary to drive sustained feeding behaviour73. Secreted NPY from AgRP neurons can also bind to Y1 receptors on POMC neurons, inducing potassium ion efflux, hyperpolarising the neuron into a state of inhibition64. Whilst most AgRP neurons co-express NPY, and are often referred to interchangeably, there are also AgRP-negative/NPY-positive neurons, which specifically project to POMC neurons in the ARC to promote feeding in both negative energy states (i.e. fasting) as well as positive energy states (i.e. diet induced obesity)74.

ARC neurons are sensitive to the fluctuations of hormonal changes and respond to dynamic metabolic cues. AgRP neurons are activated by ghrelin to increase food intake75. Ghrelin-mediated AgRP and NPY secretion is impaired in obesity, suggesting that ghrelin resistance is in part due to impaired AgRP/NPY neuron function24. Conversely, they are inhibited by leptin58 and hyperpolarised by insulin76. Insulin-mediated AgRP signalling regulates energy expenditure, whereby insulin signalling in AgRP neurons increases energy expenditure as a feature of white adipose tissue browning77. AgRP signalling drives feeding in adult mice, such that overexpression of the peptide leads to obesity, hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycaemia78. This has been shown in a biphasic manner via Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADD)-mediated activation of AgRP neurons, which drives feeding behaviour, and vice versa, by inhibitory DREADDs to reduce food intake79. Diphtheria toxin-mediated AgRP neuron ablation in adult mice obliterates food-seeking and consumption behaviour, leading to starvation80,81, although this is not entirely dependent on melanocortin signalling82. Interestingly, when AgRP ablation occurs in neonate mice, the effect is not seen, as other mechanisms are able to compensate during development83. Similarly, developmental AgRP-deficiency, with and without NPY-deficiency does not affect food intake or body weight84. In a similar fashion, developmental deletion of AgRP leptin receptor only results in a mild overweight phenotype when compared to db/db mice85, whereas CRISPR-Cas9-deletion of leptin receptor in adult mice causes extreme weight gain86. This had led the field to believe that there is a key developmental window during which the AgRP circuitry is defined, and that there is a level of plasticity that can occur to ensure metabolic homoeostasis post-development. The capacity for neuroplasticity speaks to the importance of these neurons’ ability to sufficiently respond to hormonal cues. But how do these circulating hormones access their target neurons in the ARC and how do the surrounding glia mediate these responses?

The blood brain barrier (BBB) and tanycytes

To enter the CNS, circulating hormones and metabolites must first pass the blood brain barrier (BBB). The BBB is a key feature of the neuroendocrine axis as it restricts the movement of substances from the circulation into the CNS87. The BBB is comprised of a network of cells referred to as the neurovascular unit, which comprises blood vessel endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes. Together, these cells restrict substrate movement between the blood and the brain parenchyma, to protect the hormonal and immune privilege of the CNS and maintain homoeostasis. In most regions of the brain, BBB integrity is maintained by the formation of tight junctions between the membranes of vasculature endothelia88. Tight junction proteins include the claudin family members (occludins, claudins and junctional adhesion molecules), which localise to the plasma membrane to seal together neighbouring cells, supported by intracellular structural proteins such as zonula occludens (ZO) proteins88,89. Surrounding the vessel walls are pericytes, which control blood flow by regulating vessel diameter90. Pericyte function has been suggested to influence energy homeostasis, as knockout of a commonly used pericyte marker, platelet derived growth factor receptor beta, increases energy expenditure, abrogating weight gain on a HFD91. Pericyte-specific deletion of the leptin receptor also impairs leptin action in the medial basal hypothalamus, resulting in increased food intake and fat mass92. Astrocytes (to be discussed in isolation later in this review), in addition to their role as a supporting cell for neurons, contact vessels by extending processes to form end-feet93, allowing them to regulate both the endothelia and neurons. Formation of the neurovascular unit is partly-dependent on pericytes, as aquaporin 4, a marker of astrocyte endfeet, fails to localise to vasculature when pericytes are not present90. Unlike most of the CNS, select regions of the brain including the hypothalamus have unique access to circulating factors due to the absence of a traditional BBB. Substances can enter the ARC by one of two means, either directly through the CSF at the ventricular wall of the ARC, or via the fenestrated/porous capillaries in the circumventricular organ of the third ventricle, the median eminence (ME). In addition to the traditional neurovascular unit, BBB-mediated entry into the hypothalamus is also regulated by specialised ependymal cells called tanycytes.

Tanycytes are found lining circumventricular organs throughout the brain, including the ME, and the walls of the third ventricle neighbouring the ARC94. Tanycytes have a bipolar morphology, with their cell body apex at the CSF-face of the ventricles, and long tail-like processes pointing inwards to the parenchyma. Like vasculature endothelial cells, tanycytes maintain the BBB by forming tight junctions at their apical side, forming what some call the CSF-hypothalamus barrier. Tanycytes themselves are subject to regional differences, as the strength of tanycytic tight junctions is not consistent throughout the entirety of the hypothalamus95. Along the wall of the third ventricle, ARC tanycytes lack claudin-1 and have disorganised structure compared to the ME, allowing substances such as Evan’s blue dye to more-freely enter the ARC via the CSF when intracerebroventricularly injected95.

A key function of tanycytes in the ARC and ME is to facilitate the transport of metabolic hormones into the hypothalamus. In the fasted state, tanycytes release vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) to increase endothelial cell permeability, as shown by increases in MECA-32, a marker of fenestrated vessels, allowing for increased access of metabolic hormones into the ME and the ventromedial ARC96. Tanycytes internalise ghrelin from the CSF via clathrin-mediated endocytosis97 in a GHSR-independent manner98 to allow access to the ARC parenchyma. Tanycytes have been also been reported to transport leptin into the hypothalamus via clathrin-mediated transport in an ERK-dependent manner99,100. Microdialysis experiments have shown that when leptin receptor-mediated tanycytic transport is impaired, leptin levels in the interstitial space fail to rise following IP leptin injection100. Tanycytic leptin transport has recently been reported to depend on a subpopulation of tanycytes on the floor of the third ventricle, although the exact reason for this has yet to be determined101. But this is not the only method through which leptin can enter the hypothalamus parenchyma. In addition to tanycyte expression, others have reported leptin receptor deletion on endothelial cells results in increased reward-based feeding behaviour102 and obesity103. Interestingly, other groups have not been able to identify leptin receptor-expressing tanycytes92,104,105. Rather, expression of the receptor has been proposed to be limited to neurons (within the ARC) and pericytes (outside the ARC)92. These differences in reports may be result of varying techniques, but also transgenic mouse lines used. There is less controversy over tanycytic transport of other hormones. Tanycytes express the insulin receptor and allow the hormone’s entry into the ARC, such that deletion from tanycytes results in insulin resistance106. In this study, tanycyte-specific deletion of the insulin receptor impaired the ability of AgRP neurons to respond to hormonal and food cues. The excitatory action of ghrelin on AgRP neurons was also significantly dampened106, which is a hallmark of obesity24. Assessment of the transcriptome of insulin receptor-deficient and HFD tanycytes identified mitochondrial protein localisation as a common deficit in both groups, highlighting mitochondrial stress as an important factor in disease progression106. In addition to hormonal transport, tanycytes uptake and metabolise glucose, to then shuttle lactate to POMC neurons to provide direct metabolic support107.

Recent work has shown that ARC tanycytes are key players in hypothalamic neurocircuitry. Tanycytes are activated by neuronal projections from the parabrachial nucleus, to reduce feeding in response to heat exposure108. In turn, they can also signal to hypothalamic neuron populations to trigger neuronal firing109. Optogenetic stimulation of tanycytes in the third ventricle causes ATP release, which can then depolarise both POMC and NPY neurons109. Despite acting on these two functionally opposing neuronal populations, this tanycyte activation results in acute hyperphagia, which the authors suggest is due to heterogeneity in the POMC population, with 25% of POMC neurons also expressing the Agrp gene110, adding further complexity to hypothalamic circuitry. Beyond their role in trafficking metabolic hormones, tanycytes in the ME can act as a neurogenic pool111. Blocking neurogenesis in this area attenuates weight gain and increases energy expenditure, suggesting that neurogenesis from tanycyte progenitors may occur in obesity111. Cells of the BBB and particularly tanycytes are therefore active players in regulating the neuroendocrine axis.

Appropriate maintenance of the BBB and CSF-hypothalamus barrier is key to maintaining homoeostasis and physiological function. Drops in blood glucose during fasting transiently increase ME BBB permeability96. This is coupled with the restructuring of tight junction proteins ZO-1 and claudin-1, which is then reversed upon refeeding96. In metabolic disease, plasticity of BBB function is lost, as obesity is predominantly associated with altered BBB permeability. Leptin receptor-deficient db/db mice on standard chow diet also have a leaky BBB112. BBB capillaries from animals fed a HFD downregulate occludin and claudins -5 and -12, increasing CNS permeability to fluorescent tracers compared to chow controls113. This phenomenon has also been seen in human cohorts114,115. Type 2 diabetic patients present with increased BBB permeability, indicated by increased gadolinium signal intensity during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) compared to healthy controls114. Overweight and obese women also present with increases in CSF:serum albumin ratio, which is suggestive of BBB permeability as albumin is normally excluded from the CSF by a functional BBB115. The effects of metabolic disease on BBB function can even be transgenerational. Maternal obesity impairs BBB function in offspring, as BBB disruption and tracer leakage into the ARC has been observed in neonatal mice born to obese dams116,117. Pups with obese mothers are also significantly heavier at weaning, and glucose intolerant compared to offspring of lean mothers117. This offspring effect can be reversed upon exposure to breastmilk from lean mothers, highlighting the influence of diet on BBB permeability117. Interestingly, despite this increased BBB leakiness, obese mice display impaired ability of leptin to enter the ARC via tanycytes99, indicating that there is more at play than simply BBB permeability, influencing the neuroendocrine axis.

Hypothalamic microinflammation and reactive gliosis

While it is well-established that hormonal and neuronal dysfunction of the neuroendocrine axis drives metabolic disease, exactly how or why this occurs is unclear. Emerging evidence suggests that inflammation is a major contributor to disease pathogenesis. Obesity is associated with inflammation in adipose tissue118, and increased levels of serum interleukin-(IL)5, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)119. Adipocytes in the adipose tissue of obese patients are often surrounded by “crown-like structures” of infiltrating macrophages and upregulation of activated macrophage markers CD68 and TNFα120. Interestingly, obesity-mediated upregulation of inflammatory factors in the CNS occurs prior to any increases in peripheral sites such as the adipose tissue or liver121, suggesting that metabolic disease progression may follow a “brain then body” course of events, and that preventing inflammation in the brain may be a means of preventing metabolic disease. Neuroinflammation of the CNS is well established to occur following traumatic brain injury, stroke, infection and neurodegenerative diseases122,123. There is now a growing body of work linking inflammation specifically within the hypothalamus – sometimes referred to as microinflammation—with the development of obesity.

The term “microinflammation” refers to the localised, low-grade inflammation observed in the hypothalamus during aging and metabolic disease development (reviewed in124,125). Feeding rodents a HFD significantly increases mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL6, IL1β and TNFα in the hypothalamus42,121,126,127,128. In particular, HFD consumption activates the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signalling pathway, which is necessary for weight gain, as HFD-fed rats that are also TLR4-deficient have blunted weight gain compared to controls42. TLR4 is a pattern recognition receptor that recognises lipopolysaccharide (LPS), typically released by gram-negative bacteria. ICV infusion of TLR4 antibody significantly decreases IL6, IL1β and TNFα gene expression in the hypothalamus and reduces body weight42, showing that TLR4-mediated neuroinflammation, particularly within the hypothalamus, promotes obesity. In addition to LPS, TLR4 is also activated by saturated fatty acids129,130, activating the pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathway. Compared to other tissues such as the liver, muscle, adipose tissue and kidneys, the NF-κB-activating protein IKKβ is highly enriched in the hypothalamus, but its activity is suppressed131. Upon feeding, the pathway is activated, resulting in inflammation, insulin and leptin resistance and weight gain131. Inhibiting NF-κB signalling by deleting IKKβ significantly rescues these metabolic phenotypes131. However, it is not neurons that are driving this TLR4-mediated neuroinflammation, as neurons, particularly AgRP and POMC neurons, do not express TLR442. Rather, this phenomenon appears to be orchestrated by non-neuronal glial cells.

Glial cells include astrocytes, microglia and oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Activation of non-neuronal CNS-resident glial cells, particularly microglia and astrocytes, is a phenomenon commonly referred to as “reactive gliosis”. Seminal work by Thaler et al. in 2012 observed reactive gliosis in rodent models of obesity via immunohistochemistry, showing increased hypothalamic glia cell numbers and size, and increased glial cell marker gene expression121. Surprisingly, elevated Gfap and Emri mRNA levels, markers of astrocytes and mature microglia, respectively, were increased after just one day of HFD feeding121. Obesity-induced reactive gliosis can be reversed once mice are returned to a standard chow diet after at least 4 weeks, evident by reduced GFAP intensity and microglial activation132. Newly-generated cells in the obese hypothalamus, identified by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labelling, are predominantly microglia, with few GFAP/BrdU double-positive cells133. This implies that while hypothalamic microglia undergo cell proliferation during HFD-feeding, it is likely that existing astrocytes from other brain regions are recruited to the area, perhaps by chemokine signalling. Pharmacologically blocking cell proliferation in HFD mice has been shown to prevent this microglia and astrocyte accumulation and resultant neuroinflammation, indicated by decreased cell numbers and soma size133. Blocking reactive gliosis also rescues the whole body HFD phenotype by lowering plasma IL1β and TNFα levels, reducing fat mass gain, and restoring leptin sensitivity133, further highlighting reactive gliosis as a major contributor to metabolic disease.

Clinical assessment of reactive gliosis in humans can be inferred based on MRI134. Increased MRI T2 relaxation time in the medial basal hypothalamus has been used as a surrogate marker for reactive gliosis in both mice135 and humans121,136, and is significantly correlated with fat mass132 and glucose intolerance137. Another study also correlated T2 relaxation time with BMI, fasting insulin levels and homoeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) score136.

Obesity-induced neuroinflammation also poses a risk of cognitive decline138 as chronic exposure to obesogenic diets affects the neuronal wiring within the brain. Obesity has been shown to decrease synaptic inputs onto both POMC and AgRP/NPY neurons, affecting inhibitory synapses on POMC neurons, and stimulatory synapses on NPY neurons139. Long-term HFD feeding (8 months) in mice eventually results in POMC neuron loss (approximately 25% reduction), highlighting the danger of long-term hypothalamic gliosis on physiologically crucial neuronal circuits121.

Whilst obesity is an established major risk factor for cardiovascular and liver diseases, emerging evidence suggests that obesity exacerbates neurological diseases by potentiating neuroinflammation, partly due to the presence of a leaky BBB. BBB disruption is a feature of neurological diseases including stroke140, multiple sclerosis (MS)141 and epilepsy142, all of which can involve peripheral macrophage and T lymphocyte infiltration in their pathogenesis. In addition to neuroinflammation, obesity-induced BBB leakiness has recently been shown to prime the CNS for subsequent infiltration of peripheral immune cells and parenchymal cell activation, resulting in worsened outcomes in models of MS143. In another study, the authors found that peripheral IL1β-mediated peripheral macrophage infiltration and CNS-resident macrophage activation can be dampened by closure of a leaky BBB, suggesting that chemokine release from the CNS is a potential mechanism through which obesity-mediated disease can be exacerbated by infiltrating macrophages from the periphery112.

As discussed above, hypothalamic microinflammation is strongly driven by reactive gliosis. The field of metabolic neuroscience has been largely focused on the action of POMC and AgRP/NPY neurons, but it is evident that glial cells are a significant contributor to the neuroendocrine landscape, yet the roles of these cells to the regulation of metabolism or their pathogenic contribution to metabolic disease have yet to be fully explored.

Astrocytes

Both astrocytes and oligodendroglia are derived from the neural stem cell lineage and originate from neurogenic zones such as the subventricular zone neighbouring the lateral ventricles144,145, and the subgranular zone in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus146. As the most abundant glial cell type in the CNS, astrocytes act as the major support network for neurons to maintain homoeostasis and function. Like other glia, one major role of astrocytes is to maintain synapses and promoting synaptogenesis and synaptic plasticity147. In addition to shaping neuronal connectivity, astrocytes regulate neuronal firing by recycling neurotransmitters at the synaptic cleft. Excitatory glutamate and inhibitory GABA are taken up by glutamate transporters on astrocyte endfeet, to be converted into glutamine via glutamine synthetase, which is exclusively expressed by astrocytes148. After this, the glutamine can be delivered back to the neurons for reuse149. In obesity, astrocyte-mediated glutamate clearance via glutamate transporter 1 (Glt-1) in the orbitofrontal cortex fails, resulting in impaired synaptic plasticity150. Appropriate synapse maintenance of hypothalamic neurons is necessary for metabolic health, as neuronal synapse formation onto POMC and AgRP neurons is predictive of obesity vulnerability, with decreased synapse numbers in obesity139. Astrocyte deletion of the leptin receptor impairs synaptic plasticity of these circuits, resulting in blunted actions of leptin and ghrelin on food intake, enhancing hyperphagia151.

In addition to maintaining synaptic function, astrocytes also provide metabolic support for neurons. They form gap junctions between themselves to form an astrocytic network for intercellular communication and transportation of metabolites. As part of the neurovascular unit, it is extremely rare (<1%) for astrocytes in various regions of the brain, including the hypothalamus, to be without contacts with blood vessels93. Thus, there is a strong connection between the vasculature and astrocytes, putting them in a privileged position to be the first responders to circulating metabolites and hormonal signals. Even short-term exposure to high sugar, high fat diet for as little as five days can induce transcriptomic and topographical changes in ARC astrocytes152.

Astrocytes act as an energy source to neurons by taking up glucose from blood vessels for glycolysis, to produce lactate, which enters the neuron via the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1). For glucose uptake, astrocytes are one of two cell types in the CNS (the other being endothelial cells) which express glucose transporter 1 (Glut1)153, particularly surrounding blood vessels and at the synapse154. As astrocytic Glut1 transports glucose from the endothelial cells of the vasculature via passive diffusion, astrocytes act as intrinsic energy sensors connecting the brain and the periphery. This, however, is impaired in metabolic disease. Hypothalamic Glut1 expression is reduced in models of T2D, resulting in decreased CNS glucose sensitivity to hyperglycaemia155. This ability to sense hypothalamic glucose levels is rescued by astrocyte-specific overexpression of Glut1, showing the importance of astrocytes in maintaining glucose homoeostasis155.

Astrocytes can further control energy balance by responding to hormonal signals. Astrocytes indirectly sense peripheral glucose levels by responding to insulin signalling, which in turn regulates CNS glucose uptake156. In response to increased leptin levels in obesity, astrocytes in the medial basal hypothalamus increase VEGF-A release to potentiate angiogenesis, leading to increased vascularisation, promoting hypertension157. VEGF-A has been shown to decrease occludin and claudin-5 expression on cultured endothelial cells, and GFAP-driven deletion of VEGF-A prevents infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the CNS158, showing the ability of astrocytes to influence BBB permeability. As discussed earlier, a similar effect occurs during fasting, when ME tanycytes promote capillary fenestration and BBB permeability via VEGF-A96. Astrocytes also respond to neuronal function in the context of metabolism. In response to ghrelin-mediated GABA release by AgRP neurons, neighbouring ARC astrocytes increase GFAP expression and contacts onto neurons, and become depolarised. These astrocytes, now activated, will then release prostaglandin E2 to then further activate the AgRP neurons, creating a feed-forward loop of activation159.

As mentioned in previous sections, obesity is associated with increased inflammation leading to reactive gliosis. In other fields of neuroscience, such as neurodegeneration, reactive astrocytes are often subcategorised into “A1”/pro-inflammatory/”neurotoxic” or “A2”/anti-inflammatory/”neuroprotective” phenotypes160. A1 cells are incapable of performing typically homoeostatic astrocytic functions, such as promoting synaptogenesis, phagocytosis and neuronal survival160. In obesity, hypothalamic astrocytes also acquire a pro-inflammatory phenotype, showcased by morphological changes such as increased GFAP expression139, cell number161, cell size and arborization, as well as upregulation of pro-inflammatory markers161. Hypothalamic astrocytes in the obese brain also display increased Ca2+ signalling162. In such an activated state, astrocytes have the potential to drive feeding behaviour, as chemogenetic activation of astrocytes using DREADDs can reversibly increase food intake by activating AgRP neurons163. But what triggers astrocytes to take on this pro-inflammatory phenotype and neuron-activating actions? As discussed earlier, dietary triggers such as saturated fatty acids can activate the TLR4 pathway 42, which can then induce astrocyte IL6 and TNFα expression164. Preventing astrogliosis via GFAP promoter-driven Myd88 deletion ameliorates food intake, weight gain and leptin insensitivity161. Similarly, blocking IKKβ in astrocytes decreases food intake and increases energy expenditure in mice on a HFD for 6 weeks165. In the short term, however, inhibition of astrocyte activation by inhibiting NF-κB signalling has been shown to exacerbate hyperphagia in the first 24 hours of HFD feeding166, suggesting that acute astrogliosis in response to dietary cues is a homoeostatic process intended to dampen feeding, which eventually goes awry in long term obesity.

Together, these data show how astrocytes provide more than just metabolic support to neurons, and can actively, although indirectly, control energy balance and feeding behaviour.

Microglia

Accounting for approximately 7% of non-neuronal cells in the brain167, microglia are a unique class of long-lived, self-renewing macrophages168 specifically found in the CNS169. Microglia are also notoriously hard to distinguish from blood-derived macrophages, as the two cell-types co-express commonly used immunohistochemical markers such as ionised calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) and fractalkine receptor (Cx3Cr1). Unlike blood macrophages, which originate from progenitors in the bone-marrow, microglial cells are derived from the embryonic yolk sac and enter the brain parenchyma between embryonic day (E)8.5 and E9.5169, after which they undergo clonal expansion in spatial niches across the developing brain170. During development, microglia across the brain are largely heterogeneous, although gain a more homogenous expression profile in adulthood171. After an initial spike in proliferation, microglia numbers plateau after the third postnatal week, microglial numbers reach relatively stable numbers into adulthood168. While microglial numbers in the hypothalamus are relatively stable between postnatal days (P)5 and P20, they undergo significant changes in cell morphology over time172. Between P9 and P15, these hypothalamic microglia are required to shape AgRP neuron circuitry, as microglial depletion over this period increases AgRP neuron number and leptin sensitivity, and increases intake of both their mother’s milk and solid food172. In this study, the authors limited their investigation to neonates, so the long-term consequences of postnatal microglial depletion on AgRP neurons have yet to be elucidated.

The aforementioned postnatal boom in microglial numbers coincides with key developmental a key neurodevelopmental window, during which synaptic connections are forming and axons are beginning to be myelinated. Both processes are regulated in part by microglia. Microglia have been shown to shape the postnatal brain by pruning synaptic spines to fine-turn neuronal connections173,174, modulate oligodendroglia numbers175, and regulate myelin formation/maintenance176,177. One of the mechanisms through which microglia can shape the developing as well as adult brain is by engulfing cells and other cellular components via phagocytosis. Obesity appears to dysregulate normal microglial phagocytic function, as microglia in HFD mice appear to over-engulf synaptic spines, contributing to obesity-related cognitive decline178. Recent work investigating prostaglandin signalling in microglia has shown that deletion of the prostaglandin receptor EP4 in microglia is protective against weight gain. The authors reported reduced microglial phagocytic activity, sparing POMC neuron projections in the PVH which are typically lost in obesity179.

Amongst obesity researchers, female rodents are known to be less susceptible to HFD-induced weight gain. This has been shown to be, in part, due to sex differences in microglial response, whereby male mice downregulate Cx3Cr1 expression on a HFD, compared to females which upregulate the receptor180. Cx3Cr1-deficiency in females increased weight gain, and ICV infusion of fractalkine (Cx3Cl1) into males limited weight gain on a HFD180. Fractalkine signalling in microglia is known to regulate neuroinflammation181, further highlighting the influence of gliosis on obesity neuropathology.

In their quiescent/resting state, adult microglia take on a ramified morphology, with long, thin processes, which they use to survey their environment for incoming stimuli182. Inspired by the M1 and M2 activation states of peripheral monocytes, microglia (like astrocytes) are often categorised into either M1 or M2 phenotypes, with the former representing a more pro-inflammatory state, and the latter being more anti-inflammatory183. However, as time goes on, the field is steadily moving away from binary classifications such as M1/M2184. For this review, we will use the more general terms “pro-inflammatory” and “anti-inflammatory”, recognising that this too is an unideal compromise to address a spectrum of complex cell biology. Pro-inflammatory microglia are typically identified by their amoeboid morphology, with short and thick processes, increased cytosolic area, and upregulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and inflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL1β and IL6185. On the other hand, anti-inflammatory microglia are smaller in size, with thinner processes, and express markers such as Arginase-1 (Arg1), TGFb, IL14, IL10 and IL13185. Between P5 and P20, hypothalamic microglia undergo a shift from more amoeboid to ramified phenotype, suggesting a developmental switch from pro- to anti-inflammatory state172. The reason for this has yet to be explored, but a similar “M1 to M2” switch is observed prior to remyelination186, suggesting that changes in microglial phenotype are prerequisites for various cellular processes.

It is well established that pro-inflammatory microglia/macrophage numbers in the hypothalamus are increased in obesity121,133,187. HFD feeding significantly upregulates activated microglia/macrophage marker genes Cd68 and Emri, with Emri expression in particular correlating with fat mass gain121. Microglial inflammation is necessary for obesity, as both microglial depletion and microglial-deletion of inflammatory signalling via IKKβ in adult mice, attenuates food intake and weight gain on a HFD188. Microglia also appear to be necessary to recruit peripheral blood-derived macrophages to infiltrate the ARC during HFD-feeding188. But what triggers microglia to adopt this inflammatory phenotype in response to HFD? Contrary to a previously mentioned study164, there is evidence that dietary exposure to saturated fatty acids first activates microglia, not astrocytes, resulting in microglial proliferation and upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL1β and CCl2), and neuronal stress187. This is in line with other work showing that classically-activated “M1” microglia are necessary to induce astrocytes to adopt the neurotoxic A1 phenotype160, highlighting the interconnected nature of glial cell function. Furthermore, LPS-mediated changes to ARC neuron firing are also driven by TLR4-expressing microglia189, further identifying microglia as major drivers of microinflammation in the hypothalamus. Rather counterintuitively, whilst microglial inflammation is associated with weight gain, inhibiting such inflammation has recently been found to impair glucose tolerance in both standard and HFD-fed animals190. The authors found that microglial activation can actually elicit beneficial effects by through TNFα release, which acts on POMC neurons to increase insulin production190.

These data show that not only do microglia influence the formation of hypothalamic neuronal connections during development, but they can also shape the microenvironment and directly signal to neurons to influence the course of metabolic disease.

Oligodendroglia

The term “reactive gliosis” usually refers to only astrocytes and microglia. As a consequence, the role of oligodendrocyte lineage cells in obesity-induced microinflammation remains relatively unexplored. The oligodendrocyte lineage is made up of proliferative oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) and mature oligodendrocytes. In the literature, OPCs are sometimes referred to as “NG2-glia”, given their expression of nerve-glial antigen 2 (NG2), also known as chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4). In this review, the terms “OPC” and “NG2 cell” will be used interchangeably. OPCs colonise the developing brain in distinct waves throughout embryogenesis, at E11.5 and E15, and then postnatally191. Typically, OPCs are thought to act as reserve precursor cells, to be differentiated into mature oligodendrocytes upon demyelinating events. However, emerging data has revealed that OPCs can also adopt immune function in response to injury, including upregulation of major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I) in toxin-mediated models of demyelination192 and interferon response-related endogenous retroviruses in response to traumatic brain injury193. In comparison to other neurological diseases, research investigating the involvement of NG2 cells in metabolic disease is limited. NG2-null mice display impaired thermogenesis and increased weight gain, however this is likely due to NG2-deficiency in adipocytes, as constitutive NG2 deletion in CNS-resident OPCs actually presents with leaner mice194. Of the little research that has been done investigating the role of OPCs in the obese brain, one study in particular has shown that they are necessary for leptin sensitivity195. In this study, genetic and chemical ablation of NG2-positive OPCs in adult mice causes spontaneous weight gain and increased adiposity, due in part to induced leptin insensitivity in ARC neurons195. The authors found that NG2 cells are required to maintain the leptin receptor-expressing ME dendrites, originating from ARC neurons195. This is one of the very few studies interrogating the role of hypothalamic OPCs in driving metabolic dysfunction. More work is required to fully understand the involvement of OPCs/NG2 cells in metabolic disease development, particularly in characterising their response to diet-induced obesity.

Provided transcription factors including Sox10 and myelin regulatory factor (Myrf), OPCs/NG2 cells will differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes196,197. The major function of oligodendrocytes is to produce myelin, the lipid-rich layer that wraps around axons, providing both physical and electric support198. The presence of compact myelin internodes clusters ion channels to the Nodes of Ranvier, allowing for saltatory conductance and efficient action potential firing. Like astrocytes, oligodendrocytes also provide metabolic support to neurons through the myelin sheath by shuttling lactate and pyruvate to the axon. Oligodendrocytes sense neuronal activity via glutamate binding to N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors at the paranode199, which stimulates the cell to uptake glucose and deliver glycolysis products to the axon via MCT1200,201. Oligodendrocyte loss and subsequent demyelination is a hallmark of diseases such as MS and traumatic brain injury, however the involvement of oligodendrocytes and myelin in obesity has yet to be fully explored. MRI studies have shown a negative correlation between obesity and myelin content202,203. This is not necessarily surprising, as both obesity and demyelinating diseases are accompanied/caused by neuroinflammation. Whether this reflects actual myelin loss or other myelin pathology in humans remains to be interrogated. In mice, HFD feeding can disrupt hypothalamic myelin, as obese mice sometimes present with pathological myelin whorls and mitochondrial fragmentation204.

Oligodendrocytes in most regions of the brain, including the ARC, are long-lived205,206, but ME myelin is turned over at surprisingly high rates, even in adulthood207. While the ARC is predominantly devoid of myelin and mature oligodendrocytes, the dorsal, ventricle-facing side of the ME contains relatively high numbers of oligodendroglia208. In this region, oligodendrocyte production has been found to be nutritionally regulated. A recent study has found that refeeding after fasting promotes ME OPC differentiation, and increased mTOR signalling in newly differentiated and mature oligodendrocytes208. ME oligodendrocytes are also sensitive to diet, as HFD reduces oligodendrocyte turnover and results in hypermyelination207. On the other hand, negative energy balance during calorie deficit stalls oligodendrocyte production, resulting in a hypomyelinated phenotype207. Evident from these experiments, energy status can influence oligodendrogenesis and myelination. But in turn, oligodendrocyte production can also influence food intake and energy expenditure. Blocking oligodendrocyte differentiation reduces food intake and ambulatory activity, mimicking an energy-deficient state. In addition, it also reduces Npy and AgRP gene expression, but impairs exogenous leptin signalling207. This nutrient-dependent plasticity is microglia-dependent, as microglial depletion impairs oligodendrocyte production and myelination in a similar manner207. One way in which microglia can facilitate oligodendrocyte differentiation in demyelinating disease is by phagocytosing myelin debris209. Furthermore, during development, microglia are known to regulate OPC numbers by phagocytosing excess cells175. In a previously mentioned study172, the authors performed RNA-sequencing on hypothalamus tissue of microglia-depleted mice, and detected downregulation of genes related to myelination and oligodendrocyte development. While this may not be relevant to ARC myelination, as the ARC is essentially devoid of myelin172,208, this does not rule out the involvement of microglia in maintaining the myelin content of other regions such as the ME, or relevant ARC projections in the PVH. As is the case for their precursor cells, oligodendrocyte biology is significantly under-researched compared to tanycytes, astrocytes and microglia in the context of metabolic homoeostasis, and requires further investigation.

As the field looks beyond just AgRP and POMC neurons in interrogating how feeding behaviour, whole-body metabolism and glycaemic control are regulated, now is the time to continue unravelling the intrinsic and supportive functionality of the glia that surround these neuronal populations. This review has collected evidence demonstrating how glia respond to dietary and endocrine signals to modulate the hypothalamic microenvironment (Table 1). Glial cells present themselves as a promising drug target for the treatment of metabolic disease, as dampening reactive gliosis, and subsequently hypothalamic microinflammation, can promote significant improvements on food intake and energy homoeostasis. Pharmacologically targeting neurons is restricted by the limited number of known molecular targets available. However, by expanding our scope to glial cells, we open ourselves up to a plethora of potential therapeutic targets. Taking a “regulate the regulators” approach may be therapeutically insightful and integral to preventing the neuronal dysfunction that perpetuates obesogenic behaviours. Simplistic approaches such as glial cell depletion have their obvious drawbacks, as microglia, astrocytes and oligodendroglia all have their purposes in maintaining CNS health. Rather, inhibiting glia-specific pathways may be a more practical avenue to investigate. As our understanding of reactive gliosis within the ARC is mechanistically immature, it is crucial to better understand the molecular pathways through which glia interact with neurons, and each other, during metabolic disease development.

Responses