iDC-targeting PfCSP mRNA vaccine confers superior protection against Plasmodium compared to conventional mRNA

Introduction

Prevention of malaria is currently a global health priority, with half of the world’s population living in at-risk areas and inflicting a staggering 249 million clinical cases and 608,000 deaths in 2022 alone and, by some estimates, resulted in over 150 million deaths since the 1890s1,2. The first WHO authorized malaria vaccine, RTS, S, reduces clinical malaria by ~30% over a four year period3 and is beginning to be made available in some African countries. R21, an RTS, S-related malaria vaccine with similar short-term efficacy was also recently authorized by the WHO4,5.

Early studies on Plasmodium spp. sporozoites showed that immunization with irradiated sporozoites provided sterile protection in mice6,7, monkeys8, and humans9,10,11,12,13. Notably, protection was temporally correlated with antibody titers against circumsporozoite protein (CSP)14, and most of the neutralizing antibodies targeted CSP15. CSP is among the most highly expressed sporozoite proteins16,17 and has a critical functional role in invasion of human hepatocytes18,19 and parasite development within mosquito salivary glands20. Furthermore, monoclonal antibodies against CSP prevent hepatocyte invasion by Plasmodium spp21,22,23. and antibodies induced by immunization with CSP may provide sterile protection when reaching high anti-CSP titers5,24. CSP expression is confined to the sporozoite stage. Sporozoites are deposited in the skin during a mosquito bite before finding their way through the blood to infect the hepatocyte after which the parasite is immune to inhibition by anti-CSP antibodies25. Therefore, CSP targeting vaccines must generate a robust immune response capable of neutralizing all sporozoites in a time frame on the order of minutes. For these reasons, conventional approaches to CSP vaccines have been unable to generate the robust immune responses necessary for consistent human protection.

In the last decade, scientific advances in nucleic acid vaccines have been applied to preclinical testing of novel malaria vaccines, including DNA vaccines26, self-amplifying RNA replicon constructs27 and lipid nanoparticle (LNP) encapsulated mRNA formulations28,29. Unlike protein subunit vaccines, RNA vaccines induce both strong B and T cell responses, critical for sterile immunity30,31,32,33. They are also strong inducers of T follicular helper cell responses, associated with long-lasting malaria immunity34. Vaccine designs that enhance dendritic cell targeting and activation offer enticing mechanisms for enhancing antibody titers35,36. Recent efforts fusing target antigens to cytokines, such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor37, macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha38, and macrophage inflammatory protein 3 alpha (MIP3α) have successfully enhanced vaccine-induced immune responses39. MIP3α, also known as chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20), binds to CCR6 expressed on immature dendritic cells40 and acts as a strong chemotactic agent of dendritic cells41,42,43. Co-expression of MIP3α with a target antigen, may enhance the immune response to melanoma tumors44,45, colon adenocarcinoma44, and HIV46. Importantly, fusion with MIP3α were required to elicit efficient antigen uptake, processing and presentation via both MHC I and MHC II pathways47,48, responses that elicit greater protection by attracting immune cells to the site of immunization and subsequently targeting the antigen to CCR6 on surface of immature dendritic cells. Recently, a DNA vaccine encoding CSP fused to MIP3α provided greater protection in mice than CSP alone26. Similarly, a protein subunit vaccine using CSP fused to MIP3α conferred superior protection against Plasmodium spp. in mice49 and generated higher anti-CSP antibody titers in nonhuman primates than CSP alone39. However, low protein expression and concerns over potential insertional mutagenesis have so far hindered development of other DNA vaccines for human use50. In this study, we sought to combine novel advances in RNA vaccines, lipid nanoparticles, and dendritic cell targeting to create a pre-erythrocytic malaria vaccine that elicits strong cellular and humoral responses targeting CSP.

Methods

Production of mRNA-LNP formulations

A codon optimized 3D7 PfCSP sequence (NCBI Reference Sequence: XM_001351086.1) coding for amino acids 22-374 was used in this study. The human tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) signal sequence was fused to the N-terminus of the PfCSP construct51. The tPA signal sequence and human MIP3α gene were fused to N-terminus of PfCSP to create a chemokine fusion construct. A C-terminus myc tag was added to both constructs to help detect the expressed protein. The DNA sequence was synthesized and cloned into a RNA production plasmid as previously described52. Capped, m1ψ-5’-triphosphate RNA with a 101-nucleotide poly(A) tail was synthesized and encapsulated in LNP as described52. RNA was purified using cellulose purification as previously described53. Purity was confirmed via gel electrophoresis, and transcripts were stored at −20 °C until encapsulation in LNP. LNP encapsulation of mRNA was done by rapidly mixing an acidic aqueous solution of cellulose purified mRNA with an ethanolic mixture of cationic lipid, cholesterol, polyethylene glycol-lipid, and phosphatidylcholine (Acuitas Therapeutics) as described54,55. The ionizable lipid and LNP composition are described in US patent US10,221,127. All LNP were characterized at Acuitas Therapeutics (Vancouver, BC, Canada). The mean hydrodynamic diameter of mRNA-LNPs was ~80 nm with a polydispersity index of <0.1 and an encapsulation efficiency of ~95%. Gel electrophoresis with a 2.5% formaldehyde gel was utilized to confirm the purity of both mRNA-LNP formulations. Finally, LNP-encapsulated mRNA was stored at a concentration of 1 mg/ml until further use.

Peptide synthesis

The NANP6 peptides used in this study were synthesized by LifeTein (South Plainfield, NJ). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to assess purity and demonstrated the NANP6 peptides were over 95% pure.

Protein expression and purification

A E.coli codon optimized full length PfCSP vaccine sequence was cloned into a pET47b vector and isolated by 6x His tag purification on an IMAC column as previously described48.

Western blot

HEK293T cells (Human Embryonic Kidney cells) were grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2 using DMEM media with 10% FBS and 1 mg/ml of penicillin and streptomycin. HEK 293 T cells were plated at a seeding density of 200,000 cells/well in a 6 well tissue culture treated plate (Avantor). Plates were kept at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until the culture reached ~60% confluency (24–48 h). The cells were transfected with 2 µg/well of either the CSP mRNA-LNP formulation or the MIP3α-CSP mRNA-LNP formulation and returned to the 37 °C and 5% CO2 incubator. After 48 h, protein from cell lysates and culture supernatants were run under reducing conditions on a 4–12% Bis-tris SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Protein expression was determined by probing the blot with mouse anti-myc or anti-CSP (nAb 2A10) primary antibody (1:1000, Genscript) in blocking buffer and detected using goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) + HRP (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technologies). Membranes were developed with SuperSignal chemiluminescence reagent (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and viewed under a UV transilluminator (Syngene G Box).

Immunofluorescence assay (IFA)

HEK 293 T cells were plated at a seeding density of 200,000 cells/well, topped with sterile coverslips (12 mm × 12 mm), and grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 48 h. Once 60% confluency was reached, cells were transfected with 2 μg/well of the CSP mRNA-LNP formulation, 2 μg/well of the MIP3α-CSP mRNA-LNP formulation, or sterile PBS as a non-transfected control and returned to the 37 °C and 5% CO2 incubator. After 48 h, each well was fixed for 30 min at RT with 2.5% formaldehyde & 0.05% glutaraldehyde in PBS, washed 3x with 2 ml PBS, and then blocked with 2% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at RT. Protein was detected using mouse anti-myc antibody (1:1000, Genscript) in blocking buffer for 1 h followed by goat-anti mouse Alex Fluor 588 antibody (1:500, Thermofischer Scientific). Images were captured using a LEICA DMi8 microscope as a z stack, deconvolved with LAS X.

Ethics statement

All animal procedures followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol (MO22H289). Mice were housed at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health animal facility were conditions are maintained at 40–60% relative humidity and 68–79 F, with at least ten room air changes per hour and a 14/10-h light/dark cycle. No animals or data points were excluded from analyses.

Animals, antigen dose, and immunizations

Six to seven-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were used in vaccination studies and were randomly assigned to different vaccination groups. Sample sizes were based on previous published data55,56 for testing CSP-targeting vaccines that would permit differentiating between groups. Female mice were used in this study as they are more susceptible to liver infection than male mice56, providing a stringent model to compare efficacy between two vaccines while keeping the number of animals used in the study to what is required to test our hypothesis. Following vaccinations, mice groups were blinded to the researcher prior to in vivo evaluations and un-blinded at the end of study. The order of vaccinations and challenge were randomized to avoid any confounders. Mice were anesthetized under isoflurane prior to vaccinations and IVIS imaging. Terminal bleeds and spleen collection were performed following euthanasia by CO2. Toe pinch was used to determine sufficiency followed by cervical dislocation to ensure proper euthanasia. For small volume blood collection from tail snip and parasite challenge studies, mice were held in a restrainer and placed gently back in the respective cages after these minor procedures and monitored for at least 48 h. All protocols used in animal studies were approved by Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC), under protocol MO22H289.

Standard dose: Groups of mice (n = 5/group) received 10 µg of rCSP, LNP-CSP mRNA or LNP-Mip3α-CSP mRNA diluted in 50 µl sterile 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) intramuscularly three times at 2-week intervals. Sera was collected prior to subsequent immunizations or parasite challenge for analysis.

Dose de-escalation and delayed 2nd boost: Mice (n = 7/group) received 25 µg, 15 µg and 5 µg of LNP-CSP mRNA or LNP-Mip3α-CSP mRNA diluted in 50 µl sterile 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) intramuscularly at 0, 2 and 6-week intervals respectively. Sera was collected prior to subsequent immunizations or parasite challenge for analysis.

Sporozoite challenge

Transgenic P. berghei (Pb) sporozoites expressing P. falciparum (Pf) CSP and luciferase (PbPfCSP-luc) were used in this study56. Vaccine induced protection was assessed by challenging immunized mice with 3000 PbPfCSP-luc sporozoites two weeks after the last immunization. Forty hours after the challenge, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μL of D-luciferin (30 mg/mL, PerkinElmer), anesthetized with isoflurane, and imaged on an IVIS® Spectrum in vivo Imaging System (Perkin Elmer). Bioluminescence measurements of mice abdomens were taken and normalized to those of unvaccinated mice challenged with PbPfCSP-luc sporozoites.

ELISAs

ELISAs were performed as described57 with the following modifications. Immulon 4HBX flat bottom 96-well plates (Thermofisher Scientific) were coated with either rCSP (0.5 µg/ml) or NANP6 peptide (2 µg/ml) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 2% milk in PBS for 2 h at room temperature (RT). Serum was serially diluted and added to the plates for 2 h at RT. Following washing with 1xPBS + 0.1% Tween20, goat anti-mouse HRP secondary antibody (1:2000, Cell Signaling, 7076S) was added for 2 h, washed and developed with (BioFx TMB, Surmodics) for 10 min. The reaction was stopped with (BioFx 450 nm Liquid Nova-Stop Solution, Surmodics). Plates were read at 450 nm using a BMG Fluro star omega plate reader, and end point titers were then calculated.

IgG isotyping

IgG1 and IgG2c isotyping was performed for CSP and MIP3α-CSP groups only from experiment 2. IgG isotypes were calculated using the above ELISA protocol albeit with the following modifications. For the IgG1 study, a starting 1:2000 primary dilution of sera was used and a 1:2000 dilution of the secondary antibody goat anti-mouse IgG1 was used (Invitrogen, PA1-74421). For the IgG2c study, a starting 1:2000 primary dilution of sera was used and a 1:500 dilution of the secondary antibody goat anti-mouse IgG2c was used (Invitrogen, PA1-29288).

Avidity assay

Duplicate plates were coated with either rCSP or the NANP6 peptide at 0.5 μg/ml and 2 μg/ml respectively. Serially diluted sera from each mouse were applied to wells for 2 h at RT. After washing the excess primary antibody, 100 µl of 1x PBS was added to one plate while the other received 100 µl of 5 M urea (the chaotropic agent) in PBS. Both plates were then incubated for 30 min at RT. The plates were then washed 3x with 0.1% Tween20 in PBS before addition of the secondary antibody (1:2000 HRP goat anti-mouse (Cell Signaling, #7076S) or 1:250 HRP goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen, #32430). Avidity indices were calculated using the following equation ((Titer, dilution OD = 1 in 5 M urea)/(Titer, dilution OD = 1 in PBS)*100).

Lymphocyte isolation

Under sterile conditions, mouse spleens were harvested and placed in 1x PBS on ice. Spleens were ground gently with a pestle over a 70 μM mesh filter into 50 mL conical tubes and immediately centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was fully resuspended using 1 mL ACK lysis buffer (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD) and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 3–4 min. To stop cell lysis, cells were diluted with 20–30 mL of cold 1x PBS and were then pelleted at 300 g for 10 min 4 °C. After another resuspension in 10 mL cold 1x PBS and centrifugation under the same conditions, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 4 mL freezing medium (90% FBS, 10% DMSO). Each pellet was then aliquoted into 4 tubes for cryostorage using isopropanol cooling containers (Mr. Frosty, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Tubes were stored at −80 °C for at least 4 h and then moved to −150 °C.

Intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry

Cryopreserved cells were recovered by thawing briefly in a water bath at 37 °C and then diluted slowly to 10 mL with warm complete media (RPMI, 10%FBS, 1x antibiotics, 20 mM HEPES, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% L-glutamine). Cells were spun for 7 min at 250 g and RT and then resuspended in a smaller volume of warm media to obtain a final concentration of 5 × 105–5 × 106 viable cells/well in 200 μL complete media. The cells were then rested in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 4–8 h. Samples were stimulated in duplicate wells with 1 μg of purified recombinant CSP identical to the vaccine sequence at 37 °C for 16 h. Pools of groups were stimulated for 16 h with HA peptide (JHMI Synthesis and Sequencing Facility) for the negative control or for 4 h with Cell Activation Cocktail with Brefeldin A (Biolegend) for the positive control. During the final 4 h, cells were incubated with Brefeldin-A and costimulatory antibodies anti-CD28 and anti-CD49d (Biolegend Cat. Nos 420601, 102116, and 103629). After stimulation, cells were transferred to a 96-well V-bottom plate. After centrifugation at 300 g for 5 min at RT, cells were washed with 150μL FACS buffer (0.5% Bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 1x sterile PBS) and pelleted again. Cells were stained with 100 μL/well Live/Dead (L/D) stain (1:1000 dilution in 1x sterile PBS) for 30 min at RT in the dark (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit, ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 150 μL FACS buffer and washed. Following the L/D stain, 50 μL 2% Fc block (TruStain FcX, Biolegend Cat. No 101320) were added to each well and incubated in the dark for 15 min on ice. After centrifugation, cells were stained in the dark for 20 min with an anti-mouse monoclonal-antibody (mAb) cocktail (50 μL per well, diluted in FACS buffer), including 1:500 FITC conjugated anti-CD4 (Biolegend Cat. No 100405), 1:200 PercPCy5.5 conjugated anti-CD3 (Biolegend Cat. No 100217), and 1:200 Alexa Fluor 700 conjugated anti-CD8 (Biolegend Cat. No. 155022). After centrifuging and resuspending in 50μL Fixation buffer (Cyto-Fast Fix/Perm Buffer Set, Biolegend, Cat No 426803), cells were then incubated in the dark at 4 °C overnight. For intracellular cytokine staining, intracellular anti-mouse mAb cocktail (50μL per well, diluted in 1x Cyto-Fast Perm buffer) was used to stain the cells in the dark at RT for 20 min. The cocktail includes 1:500 PECy7-conjugated anti-TNFα (Biolegend Cat. No. 506323), 1:100 PE conjugated anti-IL2 (Biolegend Cat No. 503808),1:100 APC-conjugated anti-IFNγ (Biolegend Cat. No. 505809). 100μL Cyto-Fast Perm buffer was added to each well for centrifugation at 400 g at RT for 5 min. Cells were then washed with FACS buffer and resuspended with 150 μL 1xPBS and read on the AttuneTM NxT flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Flow data were analyzed using Flow Jo software (FlowJo 10.8.1, LLC Ashland, OR). Gates were formed using negative stimulation and Full-minus-one staining controls. Averages of the duplicate wells are presented.

Statistics

For T cell assays, cytokine data was analyzed using ordinary one-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Correlation analyses of T cell assays utilized Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Differences in antibody titers were compared using two-tailed unpaired t tests (for comparison of 2 groups) and ordinary one-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (for comparison of 3 groups). In both challenge studies, luminescence values between groups were compared using ordinary one-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Percent inhibition between groups was compared using two-tailed unpaired t tests and calculated relative to naïve, sporozoite challenged mice. Prism 10 software was used for analysis, and data was maintained in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Characterization of CSP and MIP3α-CSP mRNA vaccines

PfCSP (amino acids 22-374) and a second construct with a N-terminal MIP3α tag were synthesized and encapsulated in LNP (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1). LNP-encapsulated CSP and MIP3α-CSP mRNA were stored at −80 °C and assessed on a 2.5% formaldehyde agarose gel, confirming the presence of a single band of the expected size (Supplementary Fig. 2A) and demonstrating the stability of the mRNA in the LNP formulation. Next, HEK293T cells were transfected with CSP and MIP3α-CSP LNP to assess protein synthesis. Culture supernatant and cell lysates were collected 48 h post-transfection and assayed by Western Blot using anti-CSP or anti-myc antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 2B, C). Immunofluorescence microscopy (IFA) using anti-myc antibodies also confirmed robust expression of both proteins with strong signal observed within the transfected HEK293T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Mock transfected cells were used as negative control (Supplementary Fig. 2D).

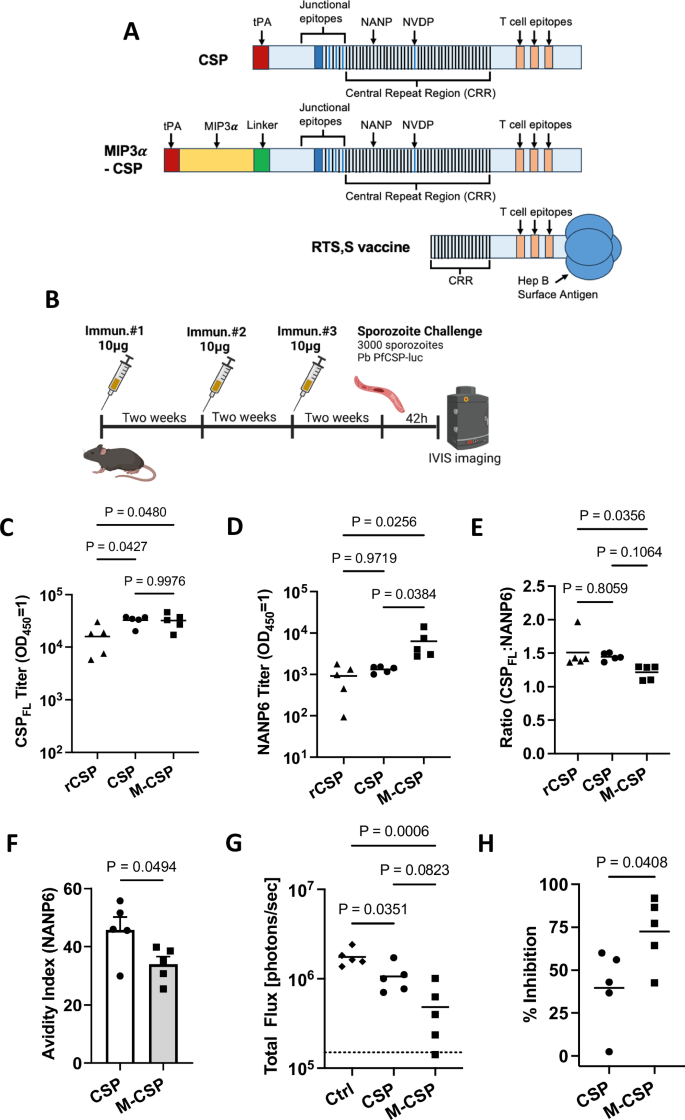

A Design of CSP and MIP3α-CSP constructs. Representations of protein sequences for full length CSP, the MIP3α -CSP construct, and the CSP construct used in the approved RTS,S vaccine are shown. Both CSP and MIP3α-CSP sequences contain the CSP C-terminal domain containing important T cell epitopes, CSP junctional region, and central repeat region of CSP with 1/4/38 copies of NPDP/NVDP/NANP respectively. For comparison, the RTS,S construct contains 0/0/19 copies of NPDP/NVDP/NANP respectively. In the MIP3α-CSP construct, the human MIP3α gene was fused to the N-terminus of 3D7 PfCSP gene via a 14 amino acid linker sequence. The tPA signal sequence is located at the N terminus of the MIP3α gene in this construct. B C57BL/6J mice (n = 5/grp) were immunized 3x at two-week intervals with 10ug MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA or CSP LNP-mRNA. Two weeks after the 3rd immunization, vaccinated and naïve mice were challenged with 3000 Pb PfCSP-luc intravenously delivered sporozoites. Forty-two h after infection, parasite liver loads, measured by luminescence, were captured. Full length recombinant CSP specific (C) and NANP6 peptide specific (D) antibody titers in mouse serum are shown. Endpoint titers (OD450 = 1) were used to quantify antibody titers for both groups. Data points are individual mice (n = 5) performed in duplicate, with horizontal lines representing mean values. Ordinary one-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons were performed to compare differences between groups. E Log 10 titer ratio of anti-full length CSP antibodies to anti-NANP6 antibodies are shown, with horizontal lines representing mean values. An ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons was performed to compare differences between groups. F NANP6 specific avidity indices are shown for antibodies from CSP and MIP3α-CSP groups. Dots represent avidity indices of individual mice. The avidity index was calculated using the following equation ((OD 1 titer in chaotropic agent)/(OD 1 titer in PBS)*100). A two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to determine p values. Bars represent mean ± SEM. G Luminescence values for each mouse in naïve, CSP and MIP3α-CSP groups were calculated in photons/sec, with horizontal lines representing group means. An ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons was performed to compare differences between groups. H Percent inhibition of liver infection was calculated relative to naïve, sporozoite challenged mice. Data is shown for individual animals, with horizontal lines representing mean values. A two-tailed unpaired t test was used to compare groups.

LNP containing MIP3α-CSP mRNA induce significantly higher anti-NANP6 antibody titers compared to CSP mRNA and recombinant CSP

The objective of this study was to test the potential for immune augmenting by chemokine fused antigen in the form of an mRNA. The impact of linking a chemokine to promote immature dendritic cell targeting on vaccine immunogenicity was evaluated by immunizing C57Bl/6J mice with the two mRNA-LNP formulations (10 μg/mouse) 3x at two-week intervals. This dose of mRNA was selected because a previous study using the same dose showed partial protection against liver infection28. Therefore, this dose may allow for a qualitative assessment between the two mRNA groups. A third group of mice was immunized with 10 μg of recombinant full length CSP protein (rCSPFL)48, formulated in Addavax adjuvant (Fig. 1B), only serving as a positive control to detect anti-CSP antibodies and excluded from further analysis. Humoral responses against rCSPFL and NANP6 peptide (six repeats of NANP) were evaluated by ELISAs in serum collected 2 weeks after the third immunization. Antibody titers against CSPFL were significantly higher in both mRNA vaccines compared to mice that received rCSPFL/Addavax, but no difference was observed between CSP and MIP3α-CSP mRNA groups (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA vaccinated mice had significantly higher anti-NANP6 peptide antibody titers compared to both rCSPFL and CSP LNP-mRNA vaccinated mice (Fig. 1D). Additionally, the proportion of NANP6 specific antibodies was significantly higher in the MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA group than the rCSPFL group but nearly identical between the rCSPFL and CSP LNP-mRNA groups (Fig. 1E). Next, we tested the strength of antibody binding to NANP6 peptide using an avidity ELISA. Interestingly, despite higher levels of overall anti-NANP6 antibodies, MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA vaccinated mice had a significantly lower avidity index than CSP LNP-mRNA vaccinated mice (Fig. 1F).

iDC targeting enhances protection against Plasmodium liver stage infection

We used P. berghei (Pb) sporozoites expressing PfCSP in place of PbCSP and luciferase (Pb PfCSP-luc) to assess the ability of anti-CSP antibodies to prevent sporozoite infection of hepatocytes58. Mice previously immunized 3x with 10 μg of either MIP3α-CSP or CSP mRNA were challenged intravenously two weeks after the third immunization with 3000 Pb PfCSP-luc sporozoites (Fig. 1B). Naïve mice were used as infection controls. No sterile protection was observed in both groups as expected from the mRNA dose used, allowing a comparison of vaccine efficacy between the groups. Both CSP and MIP3α-CSP mRNA immunized mice had an overall reduced liver stage burden relative to unvaccinated controls (39.6% and 72.5% respectively) (Fig. 1G and Supplementary Fig. 1E). Importantly, protection from liver infection was significantly greater in mice immunized with iDC-targeting MIP3α-CSP mRNA compared to CSP mRNA (Fig. 1H).

Dose de-escalation and delayed boosting enhances cellular and humoral responses induced by MIP3α-CSP mRNA

Previous studies with CSP mRNA showed greater antibody titers using a higher mRNA dose28. Similarly, delayed fractional dose boosting has also been shown to enhance antibody titer and protection from liver infection28 Therefore, we tested if dose de-escalation combined with a delayed boost may improve vaccine responses. C57Bl/6J mice were vaccinated with 25 μg, 15 μg and 5 μg of either MIP3α-CSP or CSP mRNA in LNP administered at 0, 2, and 6-week intervals (Fig. 2A). Typically, splenic cellular responses are measured in mice immunized in parallel to mice used for challenge studies. Here, we sought to determine the cellular and humoral immune responses from the animals with defined outcomes following challenge. We took advantage of the luciferase expressing parasites allowing for a definitive quantitation of protection outcomes within 42 h of challenge. Splenocytes from control, CSP, and MIP3α-CSP mRNA-LNP vaccinated mice were harvested immediately following IVIS imaging. CD4 + T cells play an important role as helpers to promote B cell antibody production and LNP vaccines have been shown to promote strong activation of CD4 + T cell responses59. CD8 + T cells also play a critical role in the prevention of liver stage infection30,31,32,33. Therefore, we measured the level and proportion of IFNγ, TNFα and IL2 expressing CD4+ and CD8 + T cells by flow cytometry following stimulation with rCSPFL (Supplementary Fig. 3A–D).

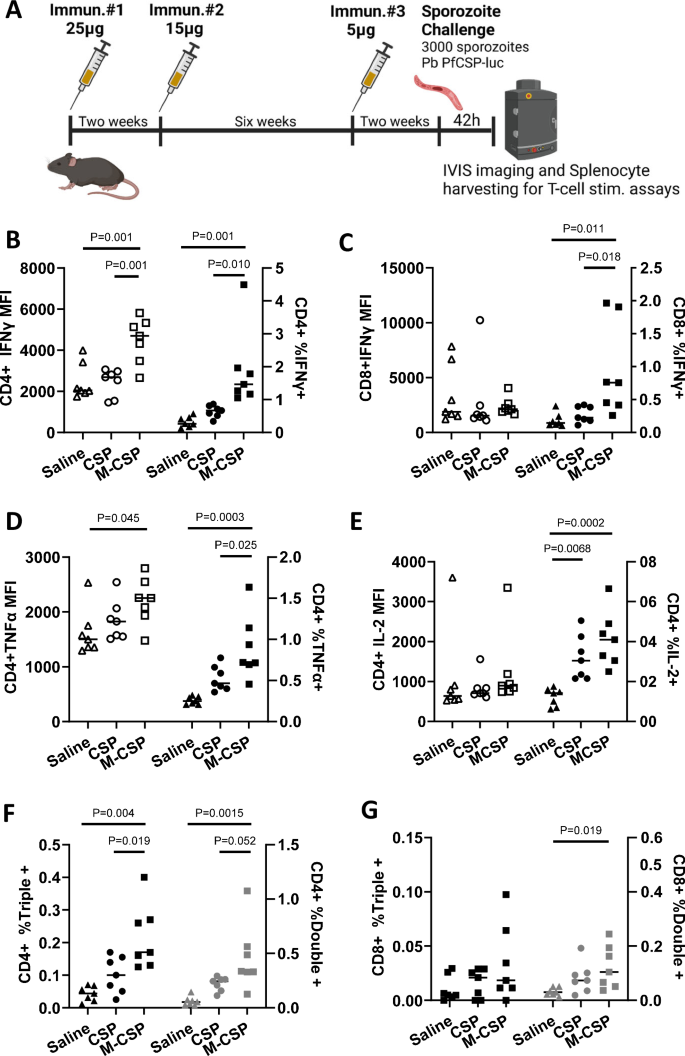

A C57BL/6J mice (n = 7/grp) were immunized 3x with 25 μg, 15 μg, and finally 5 μg of MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA or CSP LNP-mRNA. In this delayed dosing experiment, the 2nd and 3rd immunizations occurred 2 and 8 weeks after the first immunization respectively. Splenocytes were harvested from each mouse 42 h after challenge for usage in T cell stimulation assays. Cells were stained, run on flow cytometry, and gated for CD4+ (B) or CD8+ (C) T cells. Median fluorescence intensities of CD4 + IFNγ + (B) and CD8 + IFNγ + (C) T cells are shown (left). The percentage of IFN-γ+ cells among CD4+ cells (B) and CD8+ cells (C) are also shown (right). Horizontal lines indicate group means. Ordinary one-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons were performed to compare differences between groups. D, E Cells were stained, run on flow cytometry, and gated for CD4 + T cells. Median fluorescence intensities of CD4 + TNFα + cells (D) and CD4 + IL2+ cells (E) are shown (left). The percentage of TNFα + (D) or IL2+ cells (E) among CD4+ cells are also shown (right). Horizontal lines indicate group means. Ordinary one-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons were performed to compare differences between groups. F, G The percentage of CD4+ or CD8+ (G) T cells that were IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-2 triple positive (left axis) or IFNγ, TNFα double positive are shown (right axis). Horizontal lines indicate group means. Ordinary one-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons were performed to compare differences between groups.

While the percentage of CD4 + T cells expressing IFNγ, TNFα, or IL2 increased in both mRNA groups relative to control sporozoite challenged mice, the percentage of CD4 + T cells expressing IFNγ, TNFα was significantly higher in the MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA group than the CSP LNP-mRNA group (Fig. 2B, D). The percentage of IL2 expressing CD4 + T cells were also higher in MIP3α-CSP group though not statistically significant (2E). Furthermore, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD4 + T cells expressing IFNγ or TNFα were significantly higher than control mice in the MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA group but not CSP LNP-mRNA group (Fig. 2B, D). In the case of CD8 + T cells, MIP3α-CSP mRNA enhanced the proportion of cells expressing IFNγ relative to both the control and CSP mRNA groups (Fig. 2C). The role of polyfunctional antigen-specific T cells that express multiple cytokines have been shown to be associated with higher effector function compared to monofunctional T cells and correlate strongly with antibody titers60,61,62,63,64,65. Polyfunctional CD4 + T cells that secrete multiple cytokines have been observed in children following both RTS, S vaccination and P. falciparum infection66,67. Interestingly, mice immunized with iDC-targeting MIP3α-CSP had a significantly higher proportion of CD4 + T cells expressing two or all three cytokines (IFNγ, TNFα, IL2) compared to both control and CSP mRNA groups (Fig. 2F). Likewise compared to control mice, a higher proportion of double positive CD8 + T cells was seen in the MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA group but not the CSP LNP-mRNA group (Fig. 2G).

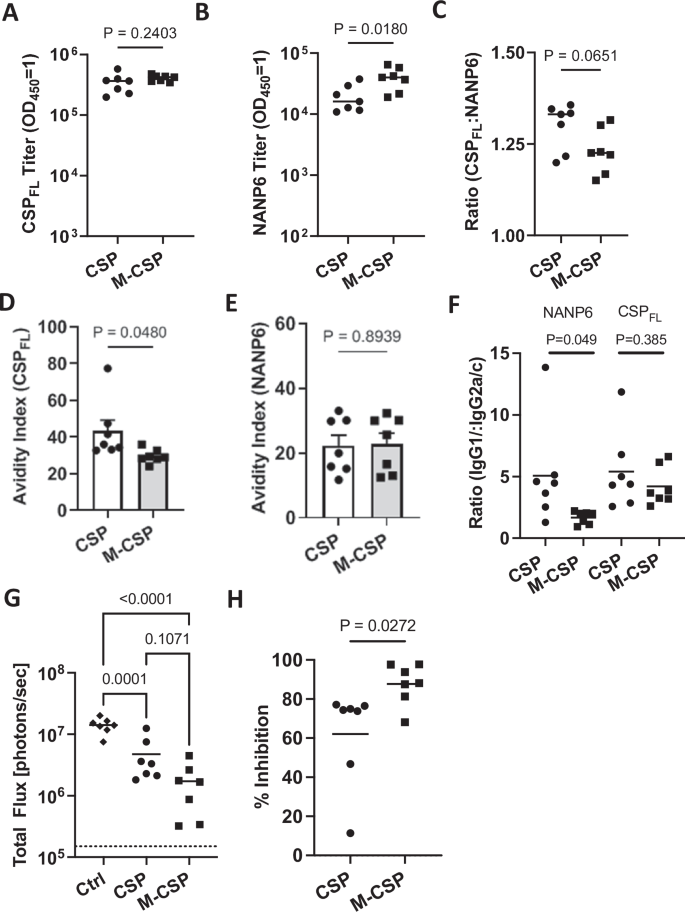

Next, we assessed humoral responses in the serum of immunized mice. While no difference in antibody titers to rCSPFL was observed between the groups (Fig. 3A), once again MIP3α-CSP immunized mice had significantly higher anti-NANP6 antibody compared to mice receiving CSP mRNA (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the proportion of NANP6 antibodies, though not significantly different, tended to be higher on average in the MIP3α-CSP mRNA group, (Fig. 3C). Avidity of antibodies induced by MIP3α-CSP was lower against rCSPFL but were similar against NANP6 compared to animals receiving CSP mRNA (Fig. 3D, E). Furthermore, while both groups showed similar IgG1:IgG2a/c ratios against rCSPFL, NANP6 specific IgG1:IgG2a/c ratios of antibodies induced by MIP3α-CSP were more balanced compared to those induced by CSP (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, we also observed a trend of increasing NANP6 titers between dose de-escalation delayed boost and standard dose groups (M-CSPdel > M-CSPstd > CSPdel > CSPstd), though not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 4G, H). The percentage of CD4 + T cells expressing IFNγ correlated significantly with NANP6 titers (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Similarly, the percentage of triple positive (IFNγ, TNFα and IL2) CD4 + T cells also tended to positively correlate with NANP6 antibody titers (Supplementary Fig. 4B), while CSPFL titer also correlated to a lesser extent (Supplementary Fig. 4E, F). This suggests a strong link between cellular and humoral responses induced by the mRNA-LNP vaccines and the immune potentiating effects of MIP3α.

A Full length recombinant CSP antibody titer in mice sera. B NANP6 peptide-specific antibody titer in mouse sera. Endpoint titers (OD450 = 1) were used to quantify antibody titers for both groups. Data points are individual mice (n = 7) performed in duplicate, with horizontal lines representing mean values. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed to compare differences between groups. C Log 10 titer ratio of anti-full length CSP antibodies to anti-NANP6 antibodies are shown, with horizontal lines representing mean values. A two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to compare differences between groups. Data is shown as mean ± SEM with individual points representing individual mice performed in duplicate. Full length recombinant CSP specific (D) and NANP6 peptide specific (E) avidity indices are shown for antibodies from CSP and MIP3α-CSP vaccinated mice. Dots represent avidity indices of individual mice performed in duplicate. The avidity index was calculated using the following equation ((OD 1 titer in chaotropic agent)/(OD 1 titer in PBS)*100). Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed to determine p values. Bars represent mean ± SEM. F The IgG1/IgG2c ratio of CSPFL specific and NANP6 specific antibodies in CSP and MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA vaccinated groups are shown. P values were calculated using two-tailed unpaired t tests. Dots represent the ratio of antibody isotypes of individual mice performed in duplicate, and horizontal bars represent mean values of each group. G Luminescence values for each mouse in naïve, CSP and MIP3α-CSP groups were calculated in photons/sec, with horizontal lines representing group means. An ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons was performed to compare differences between groups. H Percent inhibition of liver infection was calculated relative to naïve, sporozoite challenged mice. Data is again shown for individual animals, with horizontal lines representing mean values. A two-tailed unpaired t test was used to compare groups.

iDC-targeting MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA vaccine confers greater protection than CSP LNP-mRNA vaccine against liver infection in dose de-escalation, delayed-boosting regimen

The effect of dose de-escalation and delayed boosting of vaccines to protect mice against Pb PfCSP-luc sporozoite challenge was evaluated two weeks after the second boost (Fig. 2A). Sporozoite infection of the liver showed a trend towards enhanced protection of mice in both the groups compared to the first study (CSP mRNA: 62% vs 39.6% and MIP3α-CSP: 88% vs 72.5%) 42 h after challenge (Figs. 1H, 3H and Supplementary Fig. 4I). Importantly, once again mice immunized with the iDC-targeting MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA vaccine were significantly better protected from liver infection compared to mice immunized with the CSP LNP-mRNA vaccine. Like NANP6 titer, we observed a trend of increasing inhibition of liver infection in mice following mRNA dose de-escalation and delayed boost, M-CSPdel > M-CSPstd > CSPdel > CSPstd (Supplementary Fig. 4I).

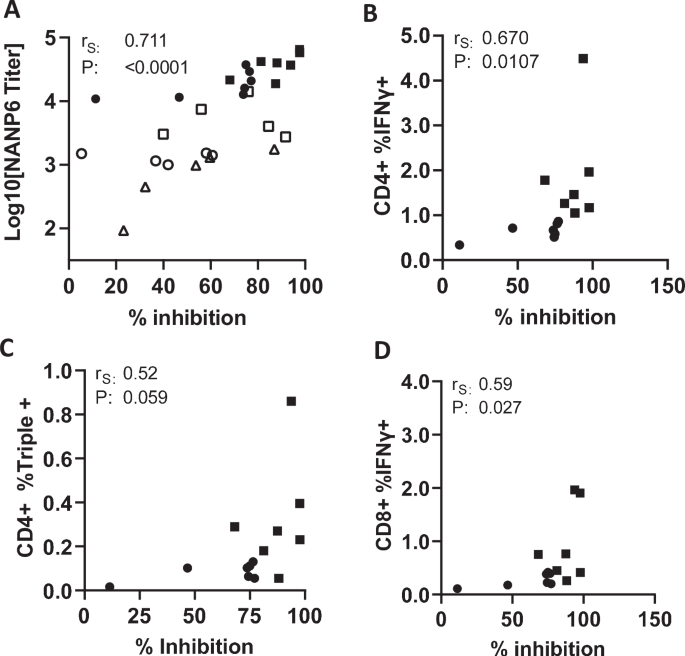

Correlates of vaccine induced protection

Recent studies demonstrate that antibody titers against the repeat (NANP) region of P. falciparum CSP correlate with protection in mice67,68,69,70,71,72 and protection from clinical malaria in humans5. In addition, protection from clinical malaria following RTS,S vaccine administration was associated with the presence of polyfunctional CD4 + T cells66. Therefore, we sought to examine possible correlations between cellular, humoral responses and protection from liver infection in these mice. This was possible with mice used in the second study since cellular and humoral responses were assessed following IVIS quantitation of liver burden in the corresponding mice. As expected, anti-NANP6 antibody titers correlated positively with anti-CSPFL antibody titers (Supplementary Fig. 4C). Importantly, NANP6 antibody titer strongly correlated with protection from liver infection (Fig. 4A), while CSPFL titer also correlated to a lesser extent (Supplementary Fig. 4D). Similarly, the percentage of CD4 + IFNγ + , CD4 + triple positive (IFNγ, TNFα and IL2), and CD8 + IFNγ + T cells each positively correlated with reduction in parasite liver burden (Fig. 4B–D).

A Relationship between log10 NANP6 peptide antibody titers (y-axis) and % inhibition of liver stage parasitemia relative to naïve, sporozoite challenged mice (x-axis). Unfilled and filled symbols represent single mice from challenge studies 1 and 2 (standard regimen and delayed, dose de-escalation regimen) respectively. Squares represent mice from the MIP3α-CSP LNP-mRNA vaccinated group, circles represent mice from the CSP LNP-mRNA vaccinated group, and triangles represent mice from the rCSPFL vaccinated group. P values were calculated using Spearman’s ranked correlation coefficient. Relationship between inhibition of liver stage parasitemia (x-axis) and the percentage of IFNγ + cells among CD4+ cells (B), the percentage of IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-2 triple positive cells among CD4+ cells (C), and the percentage of IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-2 triple positive CD8+ cells (D). Circles represent mice from the CSP vaccinated group, and squares represent mice from the MIP3α-CSP vaccinated group. P values were calculated using Spearman’s ranked correlation coefficient.

Discussion

Despite progress in malaria vaccine development, highlighted by the WHO approval of RTS,S and R21, significant work remains in producing a highly effective vaccine against P. falciparum25,73. Rapidly spreading resistance to frontline antimalarials74, a recent rebound in worldwide malaria-related deaths1, and population growth in P. falciparum endemic countries all intensify the urgency for a highly effective malaria vaccine75. While targeting the antigen CSP, both the most abundant sporozoite protein16,17 and a functionally critical antigen for hepatocyte invasion18,19, remains a useful strategy, application of contemporary advances in technology are needed for developing more effective vaccines. The recent success of LNP-encapsulated mRNA vaccine platforms, offers a novel, highly immunogenic59, and potentially durable34 strategy for vaccines against malaria. Indeed, full length PfCSP mRNA-LNP vaccines induce protective immunity in preclinical rodent models28. Novel, chemokine fusion vaccines offer a promising mechanism to enhance immunogenicity and have likewise recently been applied to malaria vaccines with encouraging results26,39,48. In this study, we tested whether immature dendritic cell targeting may further enhance vaccine efficacy. iDC targeting was achieved by using MIP3α, an 8kD (~70 amino acid) chemokine that binds to CCR6 resulting in their activation76. MIP3α fusion proteins have been shown to promote efficient uptake, processing and presentation of antigens through both MHC I and MHC II pathways46,47. Furthermore, protective immunity induced by chemokine fused antigens were mediated through targeting of iDCs46. Here, we engineered a mRNA construct coding for a MIP3α-PfCSP fusion antigen encapsulated within LNP and compared its efficacy against a standard PfCSP mRNA.

Transfection of HEK293T cells confirmed expression of both MIP3α-CSP and CSP proteins by microscopy and western blot analysis. Immunization with the MIP3α-CSP mRNA vaccine resulted in significantly higher antibody titers against the NANP repeat epitope of PfCSP compared to conventional CSP mRNA. We also observed an increase in the proportion of anti-NANP antibodies relative to full length CSP. Greater NANP responses have been associated with an increase in protection from liver stage parasitemia5,68,69. This enhanced humoral response specifically against the functionally critical NANP repeat region of CSP is a promising indicator of the MIP3α-CSP vaccine’s ability to elicit potent antibody-mediated immunity against sporozoites.

Mice immunized with MIP3α-CSP mRNA showed a significantly reduced liver stage parasite burden compared to those vaccinated with conventional CSP mRNA (73% and 40% respectively) in a standard three dose immunization regimen given in two-week intervals. Delayed dosing combined with dose de-escalation also elicited greater inhibition in mice receiving MIP3α-CSP mRNA and CSP mRNA, with the MIP3α-CSP mRNA again demonstrating higher levels of inhibition (88% and 62% respectively). However, it should be noted that none of the mice were sterile protected. This was expected as the mRNA dose used was not optimized for sterile protection but rather to allow a comparison of the two antigens, MIP3α-CSP and CSP. Interestingly, though not statistically significant, there was a trend towards higher median NANP6 titer and liver stage inhibition in the dose de-escalation, delayed boosted group relative to mice receiving standard dose (3 immunizations, two-week intervals). Future studies will be needed to optimize vaccine dose, regimen to achieve durable humoral responses required for sterile protection. Antibodies in the MIP3α-CSP group vs. CSP had relatively lower avidity for CSP. In passive transfer studies, higher avidity anti-CSP antibodies confer greater protection68,69. While antibody avidity to CSP and NANP may still be an important factor in protection, the greater relative and absolute numbers of antibodies to NANP in the MIP3α-CSP mRNA vaccinated mice in this study may have compensated for the reduced avidity of such antibodies. These findings suggest that the iDC-targeted vaccine formulation enhances protective immunity against malaria infection, potentially by promoting more robust and effective immune responses against the CSP protein on the sporozoite surface, thereby preventing hepatocyte invasion.

Fusion of the MIP3α cytokine to CSP also resulted in significantly greater TNFα, and IFNγ responses in CD4 + T cells. The proportion of CD4 + T cells producing TNFα, IL2, and IFNγ was 2-3x greater in the MIP3α-CSP vs. CSP vaccinated mice. Furthermore, with respect to IFNγ and TNFα, not only were the proportions of T cells that produced each cytokine increased in the MIP3α-CSP group, but also the splenocyte populations produced more of each cytokine, thereby amplifying cytokine effects. Interestingly, the proportion of polyfunctional CD4 + T cells was also increased following vaccination with the MIP3α-CSP mRNA vaccine. Polyfunctional T cells have an outsized role in vaccine efficacy with IL2, TNFα, and IFNγ showing synergism in their abilities to drive immune responses77. Activated dendritic cells are highly associated with polyfunctional CD4 + T cell responses to malaria78. We speculate that the iDC-targeting ability of the MIP3α-CSP mRNA elicits more polyfunctional CD4+ cells and T cell help, resulting in greater humoral responses.

The observed correlations between immune responses and protection from liver infection provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying CSP vaccine-induced immunity to malaria. Both polyfunctional CD4 + T cells and anti-NANP6 antibody titers correlated with protection, emphasizing the critical role of NANP-targeting antibodies and CD4 + T cells in preventing liver infection. Similar iDC-targeting approaches to potentiate T cell help may be utilized for other malaria vaccine candidates in a multi-stage mRNA vaccine against P. falciparum.

Responses