Impact of genotypic variability of measles virus T-cell epitopes on vaccine-induced T-cell immunity

Introduction

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease that remains a major cause of childhood morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries1. Most acute measles deaths are caused by secondary infections due to the immune suppression that develops after measles virus (MeV) infection2,3. This immune suppression occurs because MeV depletes memory cells of the immune system, leading to “immune amnesia”4,5,6,7. On the other hand, and often referred to as the “measles paradox,” MeV evokes strong humoral and cellular immune responses that mediate lifelong immunity to measles after natural infection1,8. Routine measles vaccination is the key public health strategy to reduce global measles deaths. Live-attenuated measles vaccines are safe and effective and have prevented more deaths than any other vaccine in use today9.

CD4+ T cells are key players in directing antiviral immune memory. CD4+ T cells can help B cells to generate strong and long-lived neutralizing antibody responses. Neutralizing antibodies are essential to prevent MeV infection and have been identified as a correlate of protection10,11,12. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells provide help to generate MeV-specific CD8+ T cells needed to clear infected cells13,14,15. The importance of cellular immunity is evident by development of progressive disease after MeV infection in individuals with severe deficiencies in the cellular immune compartment16,17. Despite the importance of cellular responses in measles, these have been less well studied than humoral responses18,19. Identification of T-cell epitopes facilitates the surveillance of cellular immune responses following natural MeV infection and vaccination. Investigation of the relative contribution of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the longevity and the function of the MeV-specific T cells will help to better understand their role in protection from measles. Moreover, epitope mapping allows screening for nonsynonymous mutations in T-cell epitope regions of wild-type (WT) viruses that may disrupt the cross-reactive potential of vaccine-induced T cells to circulating viruses.

Even though measles vaccination is highly effective (97% for two doses20), breakthrough cases of measles can appear, which occur when a person gets measles despite having received the vaccine. This indicates that MeV, in certain circumstances, can escape from vaccine-induced immunity. MeV infection in vaccinated individuals mainly seems to occur after intense and/or prolonged exposure to an infected individual, such as in a medical or family setting21,22,23,24. Fortunately, measles vaccination still limits the risk of complicated measles in these breakthrough cases25. Virus transmission from breakthrough infections is also possible, although this is rare. The low transmission rate from breakthrough cases may be explained by the elevated levels and rapid production of neutralizing antibodies, whereby the general mild manifestation of MeV infection in vaccinees may further limit virus shedding and effective transmission25. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that prevalent genotypes are better adapted to humans26,27. In particular, it is thought that an intermediary level of vaccination coverage may provide an environment more prone to adaptive mutations in MeV to escape immunity. In line with this hypothesis, studies have suggested that circulating MeVs with genotypes B3, D4, D8, or H1 exhibit antigenic variations that may affect vaccine effectiveness through reduced recognition by neutralizing antibodies27,28,29,30,31,32.

While T-cell epitopes, which are processed intracellularly, may face less immune pressure to mutate compared to antibody epitopes displayed on virus surface antigens, changes in T-cell epitope regions, irrespective of their origin, could still impact the effectiveness of vaccine-induced T-cell immunity. Previously, we identified 59 CD8+ T-cell epitope regions, eluted from different common HLA class I molecules of cell lines infected with the vaccine-MeV strain33. By comparison of a set of WT-MeV genomes, higher nonsynonymous than silent mutation rates were detected in various of these CD8+ T-cell epitope regions. These mutations may help circulating viruses to escape from CD8+ T cells induced by vaccination. The present study aimed to identify CD4+ T-cell epitopes in the six structural MeV proteins, i.e. fusion glycoprotein (F protein), attachment glycoprotein hemagglutinin (H protein), the matrix protein (M protein), the nucleoprotein (N protein), the large polymerase protein (L protein), and the phosphoprotein (P protein), as well as the nonstructural C protein of the vaccine-MeV strain. A bioinformatics-guided approach was applied to select MeV peptides with a high probability to bind to and to be naturally presented by multiple common HLA-DR, -DP, and -DQ alleles for population-wide epitope coverage34,35. This was shown to be a successful approach for the identification of broad-coverage SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-specific T-cell epitopes, and resulted in the detection of several mutations leading to loss of T-cell cross-reactivity to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants36,37. Here, we identified universal helper epitope candidates of vaccine-MeV that we analyzed for their T-cell responsiveness. Subsequently, we screened for the occurrence of genomic variations in the predicted HLA-II-binding core sequence of the confirmed epitopes in a large set of WT-MeVs. For this purpose, all complete genome MeV sequences obtained from GenBank of the 4 relevant genotypes (B3, D4, D8, and H1), based on a recent global update of the measles molecular epidemiology38,39, were included. In addition, we studied whether T-cell responses against two novel epitopes of MeV were affected by mutations commonly found in circulating MeVs of B3 and D8 genotypes.

Results

CD4+ T-cell epitope prediction

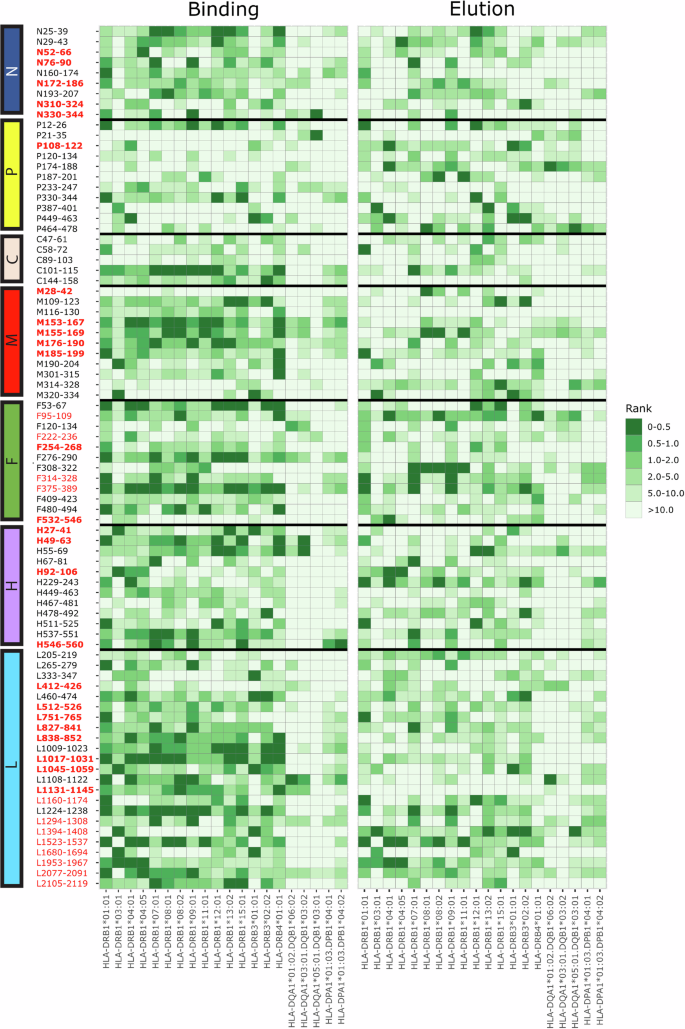

An immunoinformatics approach was used to predict 15-mer peptide sequences from seven proteins of MeV (Edmonston vaccine strain) likely to be naturally presented and to bind to at least six of 20 common human leukocyte antigen class II (HLA-II) molecules. This yielded 83 universal CD4+ helper T-cell epitope candidates, including nine putative epitopes of N protein, 11 of P protein, five of C protein, 11 of M protein, 12 of F protein, 12 of H protein, and 23 of L protein (Fig. 1). Synthetic versions of the 83 MeV vaccine strain putative epitope sequences, and variants thereof, were prepared for use in functional T-cell assays.

Heatmap depicting the 83 selected helper epitope candidates of MeV (Edmonston) with the best T-cell immunogenicity scores for 20 different common HLA-DR, DP, and DQ alleles indicated below. The green color scale indicates differences in predicted HLA-II binding affinity scores (left panel) or elution scores (right panel) to the various HLA-II alleles indicated below. Peptides with lower rank scores of 0–0.5% (dark green) represent the best-predicted T-cell epitopes. On the left side, identified universal CD4+ T-cell epitope candidates (all 15-mers) are indicated as the location of the first and last amino acid position of the corresponding MeV proteins (nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), C protein (C), matrix protein (M), fusion protein (F), hemagglutinin (H), and large protein (L)). Epitopes that were later confirmed as functional T-cell epitopes are shown in red font. The novel-confirmed epitopes that were not previously described as CD4+ T-cell epitopes are indicated in (red and) bold.

Identification of functional CD4+ T-cell epitopes

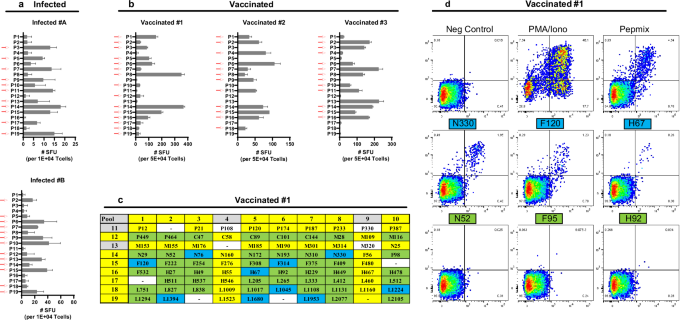

Next, we investigated if these 83 MeV-specific CD4+ T-cell epitope candidates were recognized by memory T cells. For this purpose, polyclonal T-cell lines were generated from PBMCs of recently MMR-vaccinated subjects (n = 3) or convalescent natural measles cases (n = 2) by stimulation with inactivated vaccine-MeV. MeV-specific T-cell responsiveness was pre-screened using a two-dimensional (2D)-matrix peptide pool stimulation approach, whereby responses of T-cell lines to the peptide pools, covering the full set of candidate epitopes, were measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, each of the peptides identified from the positive-tested 2D-matrix peptide pools were tested individually by stimulation of the MeV-specific T-cell lines. Peptide-specific T-cell responses were measured using a flow cytometry panel by combining assessment of activation-induced marker (CD154) and intracellular cytokine (IFN-ɣ) expression in the CD4+ T-cell population (Fig. 2b, d). Thirty-seven CD4+ T-cell epitopes of vaccine-MeV were confirmed, i.e., epitopes from N (n = 8; 89% of the candidate epitopes of N), P (n = 8; 73% of the candidate P epitopes), C (n = 1; 20%), M (n = 4; 36%), F (n = 5; 42%), H (n = 5; 42%), and L protein (n = 6; 26%) (Table 1). The T-cell lines derived from three recently vaccinated young adults and T-cell lines from two convalescent adults responded against 29 and 18 different vaccine-MeV epitopes, respectively. Ten of these epitopes were mutually recognized by T-cell lines obtained from vaccinees and from convalescent cases. Of the 37 functional CD4+ T-cell epitopes of MeV that we identify in this study, 25 appear to be novel, not archived in the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB)40, while 12 epitopes (including all 8 epitopes of N protein) contain HLA-II-binding core sequences that have been previously described. Two of our novel CD4+ T-cell epitopes appear to be included in the IEDB as functional MeV CD8+ T-cell epitopes, but not as CD4+ T-cell epitopes (Table 1).

Polyclonal MeV-specific T-cell lines obtained from two convalescent measles cases and three vaccinated subjects were stimulated with 19 various peptide pools (1 µM/peptide) in a two-dimensional peptide matrix. T-cell responses were measured by IFN-ɣ ELISPOT assay. MeV-specific T-cell frequencies are depicted in box plots and shown as means ± SD of triplicates. a T-cell frequencies of two convalescent donors (#A, #B) are presented as a spot-forming unit (SFU) per 1 × 104 cells in the left panel. b T-cell frequencies of three recently measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccinated donors (#1, #2, #3) are presented as SFU/ 5 × 104 cells in the lower panel. c Peptide pools that show a “positive” T-cell response from a representative vaccinated donor (#1) are indicated in yellow boxes. Peptides that are present in two “positive-tested peptide pools” are indicated in green boxes. Responsiveness of the T-cell lines to individual epitope candidates, selected as peptides present in two “positive-tested peptide pools”, were tested by flow cytometry for expression of intracytoplasmic IFN-ɣ and CD154 activation marker (“positive-confirmed” individual epitopes are indicated in blue boxes). d Representative flow cytometry plots of expression of IFN-ɣ (Y-axis) and CD154 (X-axis) of gated CD4+ T cells of T-cell line (donor #1) after 6 h stimulation with medium/0.3% DMSO (negative control), PMA/ionomycin (positive control), peptide mix (containing all 83 candidate epitopes), and six representative individual peptides from positive-tested pools. Individual peptides (all 15-mers) are indicated as the location of the first amino acid position of the corresponding MeV proteins (nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), C protein (C), matrix protein (M), fusion protein (F), hemagglutinin (H), and large protein (L)).

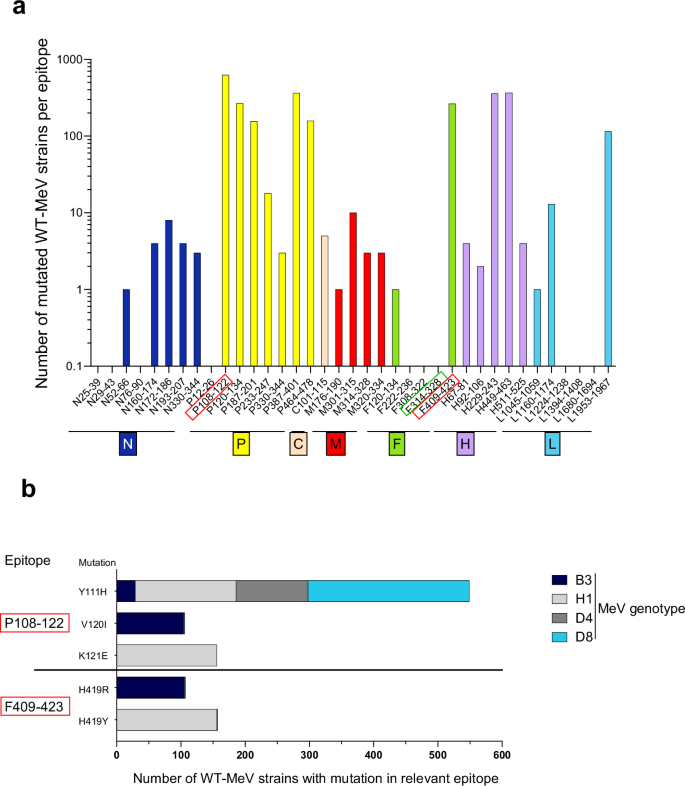

Screening of epitope sequences for nonsynonymous substitutions in WT-MeVs and sites of positive selection

Nonsynonymous mutations in T-cell epitope regions of wild-type (WT)-MeVs may lead to a diminished recognition and function of vaccine-induced T cells. In an effort to identify nonsynonymous mutations that could potentially affect vaccine-induced T-cell functionality, we compared predicted HLA-II-binding core sequences of the confirmed epitopes with corresponding amino acid sequences of globally circulating MeV strains. For this purpose, complete genome sequences of 628 WT-MeVs of the major B3, D4, D8, and H1 genotypes were selected from GenBank. In 27 out of the 37 (73%) of the predicted HLA-II-binding core sequences of the confirmed T-cell epitopes of vaccine-MeV, at least one amino acid substitution in one or more WT-MeVs were found. We have detected WT-MeV mutations in five out of the eight (5/8) confirmed CD4+ T-cell epitopes of N protein, 7/8 epitopes of P protein, 1/1 epitope of C protein, 4/4 epitopes of M protein, 2/5 epitopes of F protein, 5/5 epitopes of H protein, and 3/6 epitopes of L protein (sixth column of Table 1, Fig. 3a). Several T-cell epitopes showed to have nonsynonymous mutations in the genomes of more than 100 different WT-MeVs (Fig. 3a and Table 1). The number of observed sequence variants in WT-MeVs varied from 1 to 8 per T-cell epitope with the Edmonston vaccine-MeV as a reference strain.

a Number of the 628 screened wild-type measles viruses (WT-MeVs) having nonsynonymous mutation(s) (Y-axis) are presented per confirmed T-cell epitope (predicted HLA-II-binding core sequence) (X-axis). Peptides (15-mers) are indicated as the location of the first and last amino acid position of the corresponding MeV protein (nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), C protein (C), matrix protein (M), fusion protein (F), hemagglutinin (H), and large protein (L)). b Two T-cell epitopes (i.e., phosphoprotein (P108-122) and fusion protein (F409-423) (a, b indicated in red box) were selected for further study as they showed to have nonsynonymous mutations (Y111H, V120I, K121E and H419R, H419Y) in many WT-MeVs of the B3 (dark blue), H1 (light gray), D4 (dark gray), and/or D8 genotype (turquoise bars). The conserved T-cell epitope (F314-328) was selected as a control for further study on the impact of the mutations on T-cell responsiveness (a, green box).

In an attempt to detect specific sites under positive pressure, we conducted selection pressure analysis on 628 WT-MeV sequences from GenBank, focusing on coding positions of MeV proteins. Using FEL (fixed effects likelihood) analysis41, we calculated nonsynonymous mutation rates (dN) and the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions (dN/dS) and detected individual sites subject to diversifying selection in epitope regions (Supplementary Fig. 1). This analysis revealed that three codon positions within MeV T-cell epitopes were classified as diversifying (with p value <0.100 for evidence of positive selection), i.e., P120 within P108–122 epitope, F419 within F409–423, and H520 within H511–525 epitope, while P111 within P108–122 epitope was approaching statistical significance (p = 0.102) for evidence of diversifying positive selection. In predicted HLA-II-binding core sequences of the P108–122 and F409-423 epitopes, multiple mutations were frequently found in WT-MeV genome sequences (Fig. 3b), including in genomes of the only two genotypes, B3 and D8, that have been detected since 202139. We selected these two epitopes to investigate whether nonsynonymous mutations that are classified as diversifying selection and are commonly found in WT-MeVs, including in recently circulating genotypes B3 and D8, affect the functional T-cell response.

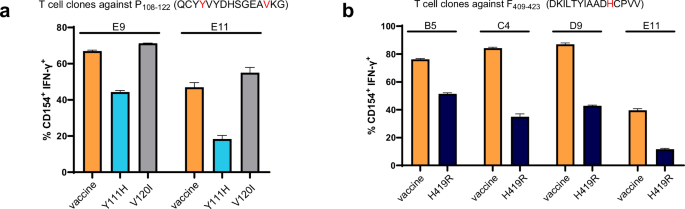

Impact of mutations in epitopes on the functional CD4+ T-cell response

We succeeded in isolating and expanding CD4+ T-cell clones against the original T-cell epitopes of vaccine-MeV, P108–122 and F409–423. Both selected epitope regions show mutation(s) in many of the circulating MeVs of genotypes B3 and/or D8. In addition, as a control, a CD4+ T-cell clone against a conserved T-cell epitope (F314–328), showing no mutations in any of the WT-MeV strains, was generated. After stimulation with the original P108–122 or F409–423 vaccine-MeV epitopes, the corresponding T-cell clones obtained from vaccinees reacted strongly by upregulation of CD154+/IFN-ɣ+ expression. In contrast, the T-cell clones showed significantly lower percentages of CD154+/IFN-ɣ+ cells upon stimulation with specific peptide variants containing mutations, P108–122 (Y111H) or F409-423 (H419R), commonly found in respectively D8 or B3 WT-MeVs (Table 2 and Fig. 4a, b). The mutation, V120I, in P108–122 epitope did not negatively influence the responsiveness of the P108–122-specific T-cell clone, but showed an equivocal to possibly slightly higher response (Fig. 4a).

a Two vaccine-MeV epitope-specific T-cell clones (E9/E11) against P108-122 were tested for their reactivity upon stimulation with antigen-presenting cells (APC) pulsed with the original vaccine epitope (orange) and to peptide variants with wild-type mutations, Y111H (turquoise) or V120I (gray) by measuring the percentage of cells expressing both the activation marker CD154 and intracellular IFN-ɣ. b The percentage of cells expressing both the activation marker CD154 and intracellular IFN-ɣ of four F409-423-epitope-specific T-cell clones (B5/C4/D9/E11) was measured upon stimulation with APC pulsed with original vaccine epitope (orange) and peptide variant with wild-type mutation, H419R (dark blue). All data (in triplicate) are shown as means ± SD. On the Y-axis, the percentage of CD154+ /IFN-γ+ T cells of total T cells is presented. T-cell response was measured at Effector (T-cell): Target (APC) (E:T) ratio of 1:1. All measured T-cell responses (CD154/IFN-ɣ) against the various peptide variants are statistically significantly different from the responses against vaccine-MeV peptides (unpaired T-test (b) or one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons (a), p ≤ 0.01).

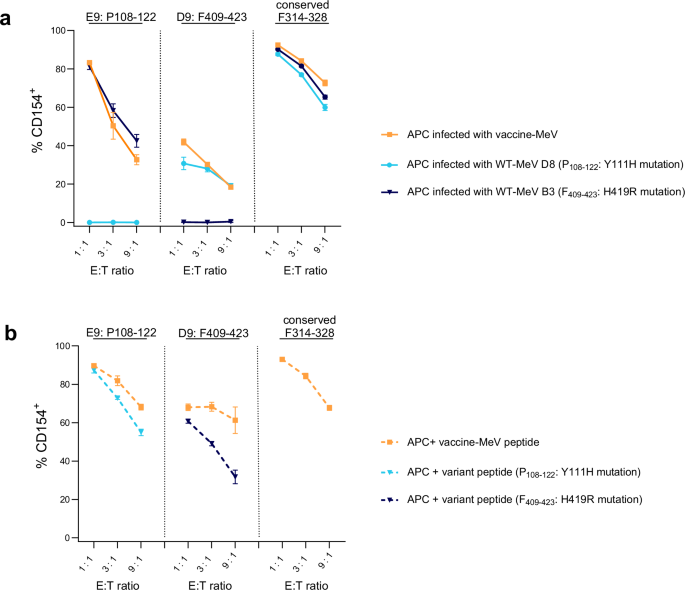

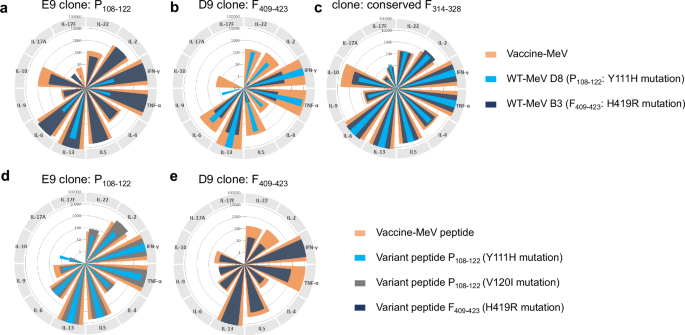

To further study the impact of the mutations on the T-cell clone’s recognition of circulating viruses, we selected a D8 MeV isolate (MVi/Zwolle.NLD/22.19[D8]) and B3 MeV isolate (MVi/Gelderland.NLD/45.22[B3]) carrying the relevant mutations, P108–122 (Y111H) or F409–423 (H419R), respectively. Interestingly, none of the P108–122 and F409–423 epitope-specific CD4+ T-cell clones reacted towards antigen-presenting cells (APCs) infected with the selected D8 and B3 circulating MeV strains having the mutation in the relevant epitope, while they did respond strongly to APCs infected with live vaccine-MeV or the WT-MeV strain without the relevant mutation (Fig. 5a). The CD4+ T-cell clone specific for the conserved T-cell epitope (F314–328) was, as expected, reactive to vaccine-MeV as well as to both WT-MeV isolates. Although the T-cell clones completely failed to respond with CD154 upregulation to the APCs infected with the relevant mutated viruses (Fig. 5a), they did respond, albeit with a moderately lower percentage of responding T cells, to APCs pulsed with the variant peptides (Fig. 5b). We next examined the impact of the mutations in WT virus isolates and variant peptides on cytokine secretion by the T-cell clones. This revealed that the T-cell clones produced clearly lower levels of cytokines upon stimulation with APCs infected with the WT-MeV carrying the relevant mutation as compared with the vaccine-MeV strain (Fig. 6a). The T-cell clones released slightly lower amounts of cytokines, especially IL-2, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-22, upon stimulation with the variant peptides compared to the original vaccine peptides (Fig. 6b). Upon stimulation with the vaccine-MeV antigens, both Th1 cytokines (IL-2, IFN- γ, and TNF-α) and Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) were produced, while some T-cell clones also made considerable amounts of IL-6, IL-10 and IL-22, and to a lesser extent IL-9. None of the T-cell clones produced IL-17(A or F) above the limit of detection (Fig. 6).

a MeV epitope-specific T-cell clones against phosphoprotein (P108-122; representative clone E9), fusion protein (F409-423; representative clone D9), or against the conserved F314-328 epitope were tested for their capacity to upregulate CD154 expression upon stimulation with antigen-presenting cells (APC) infected with vaccine-measles (MeV) strain (orange line) versus infected with wild-type (WT-)MeV of B3 (dark blue line) or D8 (turquoise line) genotype. b MeV epitope-specific T-cell clones were tested for their capacity to upregulate CD154 expression upon stimulation with APC pulsed with peptides of P108-122, F409-423, F314-328 derived from vaccine-MeV (orange dotted line) versus the corresponding variant peptides with relevant WT mutation (P: Y111H (turquoise dotted line) or F: H419R (dark blue dotted lines). All data (in triplicate) were shown as means ± SD. On the Y-axis, the percentage of CD154+ T cells of total T cells is presented. T-cell response was measured at various Effector (T-cell) : Target (APC) (E:T) ratios as presented on the X-axis.

a Cytokine secretion (IL-2, IFN- γ, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-17(A or F), IL-22) by representative P108-122-epitope-specific T-cell clone (E9) was measured upon stimulation with antigen-presenting cells (APC) infected with vaccine-MeV strain (orange) versus infected with wild-type (WT-)MeV of B3 (dark blue) or D8 (turquoise) genotype. b Cytokines produced by F409-423-epitope-specific T-cell clone (D9) was also measured upon stimulation with APC infected with vaccine-MeV strain (orange) versus infected with WT-MeV of B3 (dark blue) or D8 (turquoise) genotype. c Cytokines produced by control T-cell clone against the conserved vaccine-MeV F314-328 epitope upon stimulation with APC infected with vaccine-MeV strain (orange) versus infected with WT-MeV of B3 (dark blue) or D8 (turquoise) genotype. d Cytokine secretion by P108-122-epitope-specific T-cell clone (E9) was also measured upon stimulation with APC pulsed with vaccine-measles virus (MeV) peptide of phosphoprotein (P108-122) (orange), the corresponding peptide variants with the V120I (dark blue), or Y111H (turquoise) mutation. e Cytokines produced by a representative F409-423-epitope-specific T-cell clone (D9) was measured upon stimulation with APC pulsed with vaccine-measles virus (MeV) peptide of fusion protein (F409-423) (orange) or the corresponding peptide variant with H419R mutation (dark blue). T-cell response was measured at Effector (T-cell) : Target (APC) (E:T) ratio of 1:1.

Summarizing, MeV-specific T-cell clones not only showed reduced activation by decreased expression of the CD154, but they also produced considerably lower amounts of cytokines upon stimulation with WT viruses carrying mutations in the specific epitope regions.

Discussion

We identified 37 functional CD4+ T-cell epitopes of vaccine-MeV, including epitopes in the N (n = 8), P (n = 8), C (n = 1), M (n = 4), F (n = 5), H (n = 5), and L protein (n = 6), 25 of these epitopes had not been described before. In 73% of the predicted HLA-II-binding core sequences of these epitopes, nonsynonymous mutations were detected in one or more wild-type (WT) MeVs of genotypes B3, D4, D8, or H1 retrieved from Genbank. We show that several of these mutated epitopes are no longer recognized by CD4+ T-cells induced by measles vaccination.

Mutation frequencies in RNA viruses are typically high, and also for MeV a high spontaneous mutation rate has been estimated42. However, genetic variation and antigenic drift are significantly constrained in MeV43. The fact that MeV infection confers lifelong immunity may contribute to its limited evolutionary rate by reducing the risk of genetic drift, as reinfections are rare in naturally immune subjects. Live-attenuated MeV (MeV) vaccines, widely used from the 1970s, are largely derived from or closely related to the Edmonston strain (genotype A)44. Over a period of more than five decades, these vaccines have remained highly effective in protecting against measles20. However, MeV breakthrough infections can occur in vaccinated individuals, although these are usually associated with lower viral loads and milder disease. The number of breakthrough cases tends to rise as vaccination coverage increases25. A faster antibody decay due to the absence of natural boosting may be an explanation for this.

However, there have been reported cases of measles with pre-exposure neutralizing antibody titers to the vaccine strain above the protective threshold. This has led to arguments that genetic and antigenic variation may contribute to reduced vaccine effectiveness or even lead to the escape of certain strains from vaccine-induced immunity32,45,46. In recent years, measles genotypes B3 and D8 are the only globally circulating genotypes, and both have been linked to outbreaks in highly vaccinated populations. This raises the question of whether immune escape could be involved45. At least one study showed in sera from vaccinated children reduced neutralizing capacity against genotype B3 compared to circulating strains, D4 and H1, as well as the vaccine strain32.

Apart from reduced antibody neutralization due to genetic changes in the measles virus, mutations in B or T-cell epitope regions may also affect vaccine-induced immunity. Data from studies with other viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, hepatitis C virus, and influenza virus, suggest that viral escape from CD4+ T-cell immunity could occur36,37,47,48,49. In our study, we focused on newly discovered CD4+ T-cell epitopes of the measles vaccine virus to explore the occurrence of antigenic sequence variation in circulating WT strains. CD4+ T cells are key players in immunological memory to MeV by promoting B cells to produce antibodies, enhancing effector CD8+ T-cell responses, and to contribute to the maintenance of functional memory T-cell pools required for long-lived protection50,51,52. However, relatively little is known about the CD4+ T-cell response against MeV53. The identification of 37, including 25 novel, CD4+ T-cell epitopes in our study may help to decipher the functional CD4+ T-cell response to MeV induced by natural infection or vaccination. Moreover, naturally occurring MeV mutations in T-cell epitope regions may affect vaccine-induced T-cell functionality to WT-MeV. Here we reveal that 73% of the 37 confirmed CD4+ T-cell epitopes in our study showed ≥ 1 nonsynonymous substitution(s) in sequences of WT-MeVs with genotypes B3, D8, or H1.

We remarkably often found nonsynonymous substitutions in CD4+ T-cell epitope regions of the P protein, followed by epitope regions of H protein. For one P protein epitope (P108–122), even eight different genetic peptide variants were found among the 628 WT-MeV genome sequences. In contrast, CD4+ T-cell epitopes of the N protein hardly showed any mutations in WT-MeVs (Fig. 3). Based on real-time tracking of MeV evolution, relatively high genetic diversity of coding regions of MeVs is observed in N protein, V/P protein, and H protein, whereas lowest diversity is found in L protein, F protein, and M protein54. This is consistent with our findings, except for the low frequency of mutations that we found in N protein epitopes. Nevertheless, this can be explained by the fact that all of our confirmed CD4+ T-cell epitopes are located in the N-terminal part of N protein (location N25–344), while the high genetic diversity of N protein starts from amino acid position 406 and beyond (N406–525). One might argue that especially mutations of the T-cell epitopes of F and H proteins, which are target proteins for MeV-specific neutralizing antibodies, might reduce neutralization responses to MeV. CD4+ T cells targeting these epitopes, which are efficiently presented by F and H protein-specific B cells through B cell receptor-mediated uptake, can directly assist the production of virus-neutralizing antibodies through CD154 co-stimulation and/or cytokine secretion. We found mutations in only two out of the five confirmed T-cell epitopes of F protein and in all five epitopes of H protein. In one epitope of F protein, and in two epitopes of H protein mutations in more than 250 WT-MeV strains were found. However, CD4+ T cells that target other MeV proteins can also aid in producing virus-neutralizing antibodies. F or H protein-specific B cells can engulf whole viral particles. This allows them to display other viral proteins on HLA class II molecules to their matching CD4+ T cells. This interaction may also activate F or H protein-specific B cells leading to antibody production through co-stimulation and cytokine release. Therefore, probably also mutations in CD4+ T-cell epitopes of other MeV proteins than F and H proteins can negatively impact (virus-neutralizing) antibody responses.

We hypothesized that mutations in epitope regions of WT-MeVs, may negatively impact the functional responsiveness of vaccine-induced T cells to these WT viruses. To test this hypothesis, we generated CD4+ T-cell clones against two original T-cell epitopes from vaccine-MeV, namely P108-122 and F409-423. These two epitopes have mutation(s) in many WT-MeVs of currently circulating genotypes B3 and/or D8, and amino acid sites (P111, P120, F419) within these two epitope regions were suggested to be under diversifying positive selective pressure in our FEL analysis. Here we show that T-cell clones specific to one of these two vaccine-MeV epitopes were completely nonresponsive to WT-MeV strains having mutations in the predicted core sequences of these epitopes. Using various peptide variants, an impaired response of the vaccine-specific T-cell clones directed against P108–122 and F409–423 epitopes could be attributed to the P: Y111H, and the F: H419R mutation commonly found in WT-MeVs (Table 2). However, despite the reduced response against certain peptide variants, a clear T-cell reactivity was still evident that was completely lacking against the WT virus isolates. This indicates that the mutations in the WT viruses probably lead to disruption in the processing and presentation of the relevant epitopes by antigen-presenting cells. Mutations in T-cell epitopes can affect HLA binding and presentation, processing, and/or T-cell receptor (TCR) recognition. Additionally, if a mutation causes the TCR face of the epitope to resemble those in the human proteome, it may lead to a loss of immunogenicity due to tolerance55. Circulating MeVs can apparently carry mutations that result in loss of recognition by vaccine-induced T cells. This does not necessarily mean that these mutations were driven by evasion of existing cell-mediated immunity. The mutations could also result from other aspects of improved fitness of the virus, such as increased transmission or replication efficiency. Previously, we found that also the majority of CD8+ T-cell epitope regions of circulating MeVs had genomic variations, with amino acid substitutions (dN) occurring at a higher rate than silent nucleotide substitutions (dS)33. Interestingly, in that study, P111, as the first codon of an HLA-I eluted CD8+ T-cell epitope (P111–121), was also noted to be subject to mutational variation. This cytotoxic T-cell epitope was found to be one of the most abundant HLA-A3-restricted epitopes, which was also presented in the context of HLA-A11. Therefore, this P:Y111H mutation might also affect the response to this particular CD8+ T-cell epitope.

The advantage of our method of epitope mapping using polyclonal T-cell lines generated by whole virus antigenic stimulation, rather than using synthetic peptides, is that it allows T cells to recognize real viral structures generated by proteolysis and presented by HLA class II molecules on antigen-presenting cells. A caveat of this study is that T-cell lines were derived from only five individuals, which means that not all relevant HLA class II alleles may have been represented. Hence, apart from the 37 confirmed epitopes, additional functional T-cell epitopes could exist among the set of 83 predicted universal helper epitope candidates of this study.

In summary, measles vaccination is highly effective in preventing disease. However, it is important to monitor measles cases in vaccinated individuals to understand their potential susceptibility after intense and/or prolonged exposure to an infected person and to assess the risks for those vaccinated long ago. In the present study, we discovered novel functional T-cell epitopes in measles vaccine virus proteins that are associated with sequence variations in circulating WT-MeV strains. We show here that mutations in these T-cell epitope regions can affect functional T-cell responses to WT-MeV. Due to the great diversity of the T-cell repertoire, a limited number of mutations may ultimately have a modest impact on the entire memory T-cell response. However, the impact may be greater if mutations occur in multiple immunodominant epitopes. Overall, mutations in T-cell epitope regions found in MeV genotypes circulating in countries with high vaccination rates may confer a selective advantage by escaping vaccine-induced T-cell immunity. Host-adaptive mutations may contribute to an increased incidence of breakthrough infections. Understanding the interplay between vaccine-induced immunity, WT-MeV strains, and mutational escape is vital for effective measles control programs. Therefore, apart from vaccination, which remains crucial for preventing measles, efforts to improve (molecular) surveillance are essential to maintain progress in measles elimination.

Methods

Clinical samples

Blood samples used in this study were collected from three young adults (18–20 years) 28 days ± 1 day after a third measles-mumps-rubella (MMR-3) vaccination, and from two adults (25–50 years) at 3–12 months after natural infection with MeV B3 genotype. The recently vaccinated subjects were participating in a Dutch intervention study whereby young adults received an MMR-356, and the subjects with natural measles infection were participating in a Dutch observational longitudinal study (ImmF@ct)57. The studies were approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committees United (MEC-U; EudraCT 2016-001104-36/ICTRP: NTR5911) and the Ethical Review Board METC UMC Utrecht (International Clinical Trial Registry Platform (ICTRP): NL9775), respectively. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All trial-related activities were conducted according to Good Clinical Practice, which included the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Within 24 h after blood sampling, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from heparinized blood samples by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep, Progen, Heidelberg, Germany) and cryopreserved at −135 °C until use.

In silico prediction of CD4 + T-cell epitope candidates

The amino acid sequences of the following MeV proteins of the Edmonston vaccine strain were used: N protein (UniProtKB: P04851), P protein (P03422; including the part that is identical to V protein, i.e., amino acid sequence 1 to 231), (nonstructural) C protein (P03424), M protein (P06942), F protein (P69353), H protein (P08362), L protein (P12576). The following 20 common HLA-II types were selected for HLA Class II motif prediction (based on a previously described panel35, and our previous studies36,37): HLA-DRB1*0101, 0301, 0401, 0405, 0701, 0801, 0802, 0901, 1101, 1201, 1302, and 1501; HLA-DRB3*0101 and 0202; HLA-DRB4*0101; HLA-DQA1*0501/HLA-DQB1*0301; HLA-DQA1*0301/HLA-DQB1*0302; HLA-DQA1*0102/HLA-DQB1*0602; HLA-DPA1*0103/HLA-DPB1*0401; HLA-DPA1*0103/HLA-DPB1*0402. NetMHCIIpan-4.0 (accessed: 09 March 2023)34 was used to predict the binding affinity as well as the likelihood to be naturally presented via the selected 20 different HLA-II alleles. As input, all possible 15-mer peptides spanning the whole protein sequences were used. For this purpose, both the % rank score of the binding affinity prediction (BA data) and the % rank score of the likelihood of a peptide to be naturally presented (EL data) for each of the selected HLA-II alleles were considered. The % rank scores normalizes prediction score by comparing to prediction of a set of 100,000 random natural peptides34. Criteria for peptide selection were likely to be naturally presented or to bind to at least six of 20 common human leukocyte antigen class II (HLA-II) molecules with a % rank score <2.00 for BA or EL data of at least one HLA-II allele, plus % rank score of BA or EL data between 2.01 and 10.00 for at least five different HLA-II alleles. Subsequently, the cumulative predicted HLA-II-binding core sequence of each of the best-predicted 15-mer epitope candidates were determined by taking the two amino acid positions closest the N-terminus and C-terminus, respectively, considering all core sequences of the 20 HLA-II alleles as revealed by NetMHCIIpan-4.0.

MeV amino acid sequence alignment and variability analysis

Whole MeV genome sequences from 628 globally circulating MeVs with the common genotypes, i.e., B3 (n = 105), D4 (n = 112), D8 (n = 253), and H1 (n = 158)38 available on GenBank were downloaded on June 26, 2023. MeV sequence of the Edmonston strain, GenBank accession ID AB046218.1, was used as a representative for measles vaccine strains. Sequences were aligned using the MAFFT (multiple alignment using fast Fourier transform) online service58. Aligned nucleotide sequences of MeV genomes were subsequently translated to amino acid sequences using MEGA7 for each gene separately59. Variation between amino acid sequences of the cumulative predicted HLA-II-binding core sequences of MeV CD4+ T-cell epitopes and corresponding deduced amino acid sequences in circulating MeV strains was analyzed in BioEdit version 7.2.560. For a limited number of MeV strains in the analysis, nucleotide sequence data with sufficient accuracy was not available for all locations of the complete MeV genome. These viruses were still included in the analysis, provided that the full sequence of the epitope was available. In addition, fixed effects likelihood (FEL) analysis was performed to identify sites that may have experienced pervasive diversifying or purifying selection41,61. The nonsynonymous rates (dN) and the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions (dN/dS) were individually tested for each site. Values of dN/dS significantly above 1 are unlikely to occur without at least some of the mutations being advantageous, and indicates diversifying positive selection.

Peptides and two-dimensional matrix design for peptide pools

MeV protein-derived peptide sequences (15-mers) selected by the in silico prediction algorithm were synthesized (JPT, Berlin, Germany) (Table 1). In addition, one customized peptide mix was made containing all 83 selected epitope candidates (“pepmix”) (JPT, Berlin, Germany). All single peptides and “pepmix” were resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to 10 mM and 300 µM/peptide, respectively. Single peptides were either pooled into 19 peptide pools, each containing 8–10 peptides according to a two-dimensional (2D-)matrix design (Fig. 2c) and diluted in PBS to a stock concentration of 100 µM/peptide (PBS/10% DMSO), or diluted per single peptide in PBS to a stock concentration of 1 mM/peptide (PBS/10% DMSO). Single peptides and “pepmix” were subsequently diluted with culture medium (2% HS/AIM-V) to a working concentration of 50 µM (PBS/0.5% and 16.7% DMSO, respectively)

An additional set of selected peptide variants was ordered. Sequences of these peptide variants were based on functionally confirmed functional CD4+ T-cell epitopes with amino acid substitutions in the predicted HLA-II-binding core sequence representing the mutations found in commonly circulating strains (Table 2). The peptide variants were also resuspended in DMSO, and then diluted with PBS and culture medium to a stock concentration of 50 µM (PBS/0.5% DMSO).

The final DMSO concentration of the various peptide formulations for T-cell stimulation was maximal 0.3% equal to the negative DMSO control.

Generation and inactivation of MeV Stocks

Plaque-purified MeV (Edmonston B vaccine strain)33 and MeV isolates of genotype B3 MVi/Gelderland.NLD/45.22[B3] and genotype D8 (MVi/Zwolle.NLD/22.19[D8]) were collected from measles patients from the Netherlands. Obtained measles virus sequences are available in GenBank, respectively, accession numbers PQ287420 and PQ287421. Viruses were propagated in Vero cells (vaccine-MeV) or Vero/hSLAM cells (WT-MeV)62 in DMEM containing 2% FCS. MeV virus was harvested at peak cytopathic effect, and centrifuged (800×g). Virus stocks were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use. Inactivated vaccine-MeV was prepared by exposing the virus to ultraviolet-C irradiation (UVC) (254 nm, 2 min at 1000 mJ/cm2) (UVC 500, Hoefer). Sequences of relevant epitope regions in vaccine- and WT-MeV were verified by an amplicon-based sequencing protocol on the MinION platform.

Generation of MeV-specific T-cell lines

In order to generate T-cell lines from subjects recently immunized with or exposed to MeV, frozen PBMCs of three vaccinated subjects and two convalescent measles cases were thawed and cultured for two weeks at 2 × 105 PBMCs/well in 96-well round-bottom plates containing T-cell culture medium. Ultraviolet-C (UVC)-inactivated MeV (at the same concentration as at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for live virus) and recombinant human (r)IL-2 (1 ng/mL, 130–097–743, Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) was added to T-cell medium consisting of AIM-V medium (12055–083, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 2% human AB serum (H6914, Sigma, Kawasaki, Kanagawa). If necessary, wells were split on days 4, 7, and 11, and fresh culture medium supplemented with rIL-2 (final concentration: 1 ng/mL) was added. If there were enough cells on days 13–14, T cells were stimulated with the various peptide pools for testing by ELISPOT as described below, and the remaining (unstimulated) cells were cryopreserved at −135 °C (≥1.5 × 106 per vial). If there were not enough cells on days 13–14, a second round of expansion of the T-cell lines was performed in 96-well plates by aspecific stimulation of 1 × 104 T cells per well with 1 × 105 gamma-irradiated (2000 rad) allogeneic PBMCs from three different donors as “feeder cells” in culture medium supplemented with 1 µg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA, Sigma) and 5 ng/mL rIL-2. Ten to 14 days later, T cells were harvested for testing by ELISPOT, and remaining (unstimulated) cells were cryopreserved at −135 °C until use.

Generation of epitope-specific T-cell clones

Epitope-specific T-cell clones were generated from MeV-specific T-cell lines obtained from two vaccinated subjects that responded to epitopes harboring mutations in the predicted HLA-II-binding core sequence commonly found in circulating genotypes B3 and D8 (Table 2). In addition, as a positive control, a T-cell clone was generated to a conserved MeV epitope that did not show any mutations in the predicted HLA-II-binding core sequence of any of the circulating MeV strains. For this purpose, selected T-cell lines were thawed, and seeded at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well. Cells were cultured for 6 h in a T-cell culture medium containing the relevant MeV peptides (1 µM), 2 µM monensin was added after 1 h of culture, and anti-CD154 (1:100, clone 24–31; BioLegend) was added for the last 4 h of culture. After each of the peptide stimulations, CD4+/CD154+ positive cells were sorted with the FACS Melody cell sorter (BD) at 1 cell/well in round-bottom 96-well plates. T-cell clones were stimulated with 1 × 105 feeder cells/well consisting of gamma-irradiated (2000 rad) allogeneic PBMCs from three different donors in culture medium supplemented with 1 µg/mL PHA and 5 ng/mL rIL-2.

IFN-ɣ ELISPOT to identify peptide pools containing functional T-cell epitopes

T-cell lines were tested for their reactivity to the 19 different peptide 2D-matrix pools (Fig. 2c) in an IFN-ɣ ELISPOT. Multiscreen filtration ELISPOT plates (Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA), Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), MSIPS4510) were prewetted with 35% ethanol for ≤1 min and washed with sterile water. Plates were coated overnight (4 °C) with 5 μg/mL antihuman IFN-ɣ antibodies (1-D1K, Mabtech, Stockholm, Sweden), washed with PBS, and then blocked for at least 30 min with AIM-V medium with 2% human AB serum. T-cell lines were plated at 1 or 5 × 104 cells/well (dependent on available total cell amounts), and incubated for 20 h in presence of the measles peptides, i.e., pepmix or with the peptide pools of the 2D-matrix model (1 μM/peptide). Cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in 100 μL AIM-V supplemented with 2% human AB serum. DMSO and PHA (1 µg/mL; Sigma) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Subsequently, plates were washed and incubated for 1 h with 1 μg/mL antihuman IFN-ɣ-detection biotinylated antibody (7-B6–1, Mabtech) in PBS-0.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Plates were washed and incubated with Streptavidin–poly–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Mabtech) in PBS-0.5% FBS for 1 h. After washing, plates were developed with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Mabtech). Spots were analyzed with CTL software. The number of spots from negative DMSO controls was subtracted from total spot numbers induced by antigen-specific stimulation; more than five spots, after background subtraction, were considered to indicate a positive result.

T-cell stimulation for flow-based T-cell assay and cytokine release assay

T-cell lines were thawed and plated at 18,000–50,000 cells/well. T cells were stimulated for 6 h with “pepmix” (containing all 83 epitope candidates), with individual peptides from the “positive-tested 2D-matrix peptide pools” (each at 1 μM/peptide) or as a negative control with culture medium containing 0.3% DMSO. To assess the responsiveness of the T-cell clones against live MeV or against individual (variant) peptides, Epstein–Barr virus-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (BLCL) were used as antigen-presenting cells (APC). Autologous BLCL were generated from PBMCs as previously described63. BLCL were either infected with live vaccine-MeV or B3 or D8 wild-type (WT) MeV (all at MOI of 0.5) for 48 h or pulsed with the relevant measles (variant) peptides for 2 h (at 1 μM/peptide) or as negative control with culture medium containing 0.3% DMSO. Infected BLCL were subsequently stained for H protein expression by flow cytometry to estimate the percentage of MeV-infected cells as described below. The BLCL cells that were infected with the vaccine-MeV strain were mixed with uninfected BLCL cells to achieve a similar percentage of H protein-positive (i.e., MeV-infected) antigen-presenting cells as for BLCL infected with the WT-MeV strains. Subsequently, infected or MeV peptide-pulsed or negative control (medium containing 0.3% DMSO) BLCL cells were harvested prior to co-culture with T cells. CD4+ T-cell clones were seeded at 25–50,000 cells/well in triplicate in a 96-well plate (for flow cytometry analysis). T-cell clones were stimulated with (variant) peptide-pulsed BLCL or various numbers of the relevant MeV-infected BLCL to obtain E:T ratios of 1:1, 3:1, or 9:1. Cells were harvested after 6 h of co-culture for flow cytometry-based T-cell analysis.

CD4+ T-cell clones were seeded at 25–50,000 cells/well in monoplo in 96-well plates (for cytokine release testing), because there were not enough cells available for triplicates. T-cell clones were stimulated with BLCL pulsed (variant) peptides or with MeV-infected BLCL at an E:T ratio of 1:1. Supernatants were collected after 24 h for cytokine release assay.

Flow cytometry-based assay to determine the percentage of MeV-infected antigen-presenting cells

Infected BLCLs were stained for expression of H protein (with unconjugated in-house mouse anti MV-hemagglutinin monoclonal antibody 28-10-8 and secondary goat anti-mouse Ig FITC (BD, 349031)) to be able to estimate the percentage of MeV-infected autologous EBV-LCL cells as antigen-presenting cells.

Flow cytometry-based T-cell assays

To assess MeV-specific T cells, during the last 5 h of T-cell line or clone stimulation, a mixture of brefeldin A (1 µg/ml) and monensin (2 µM) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was added. Cells were stained for antihuman CD3 (clone HIT3A; BioLegend), CD4 (clone SK3), CD8 (clone RPAT8), and CD56 (clone NCAM) (all BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NY, USA). After fixation and permeabilization, using FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), cells were stained intracellularly for antihuman, CD154 (clone 24–31; Biolegend), and cytokines: IFN-ɣ (clone 4S.B3; BD Bioscience), IL-2 (clone MQ1–17H12; Thermo Fisher), or TNF-α (clone Mab11; Thermo Fisher). Cells were acquired on a FACS Symphony A3 analyzer (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo (V10, Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). Depending on total cell yield per T-cell line, 16,000 to >100,000 events were acquired that included 3400–27,000 CD4+ T cells. For epitope identification, a positive T-cell response to peptide stimulation was defined as: (1) after subtraction of background of negative control (culture medium/0.3% DMSO), at least 0.1% of CD4+ T cells were CD154+/IFN-ɣ+ double positive, while the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IFN-ɣ+ signal was ≥1500, (2) additionally, either at least 0.1% of CD4+ T cells were IFN-ɣ+ after relevant background subtraction for this cell fraction, or at least 0.1% of CD4+ T cells were CD154+ after corresponding background subtraction.

Cytokine release assay

Cytokine release of epitope-specific T-cell clones was measured after 24 h of MeV-specific stimulation. For this purpose, cell-free culture supernatant was collected in triplicate to quantify levels of IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-17(A or F), IL-22 in a multiplex bead-based assay (LEGENDplex Human Th cytokine panel (12-plex), 741028; BioLegend) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and using FACSCanto II (BD).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in Prism (version 9.3.1; GraphPad Software). All T-cell data were shown as means ± standard deviation (SD). T-cell responses against the various MeV peptide variants of WT-MeVs were compared with vaccine-MeV counterparts by unpaired T-test or one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Responses