Impacts of poroelastic spheres

Introduction

In an elastic collision, kinetic energy is transformed into stored elastic energy, which is then transformed to kinetic energy again. However, collisions are imperfectly elastic, and energy dissipation due to different mechanisms occurs. Here, we study such energy dissipation in bouncing spheres: our objective is to unravel the intricate interplay of different energy dissipation forms in the particular case of wet poroelastic spheres, specifically liquid-filled foam balls and hydrogel spheres. Bouncing of hydrogel balls have been first studied in 2003 by Tanaka1,2 who revealed that hydrogel spheres can undergo strong deformations upon impact without cracking and measured a strong variation of the coefficient of restitution with the impact velocity: Part of the initial kinetic energy is dissipated during the deformation. He also measured the reaction force of a deformed hydrogel sphere and showed that it deviates from Hertz’s law for strong deformations. Later, Waitukaitis et al.3 studied the bouncing of hydrogel spheres upon a hot surface and measured restitution coefficients, which can be higher than unity. They explained these measurements by the coupling between the elastic deformation and the Leidenfrost effect coming from the evaporation of the water film covering the hydrogel. As the hydrogel is filled with water and is permeable, the evaporated water film is regenerated between each bounce and remains present for multiple rebounds above the hot surface. Conversely, impacts of filled open-cell foam balls have not yet been studied to our knowledge. However, deformations of foam materials have been studied previously under different conditions due to their applications in shock absorbers. In 1966, Gent and Rush4 first proposed a theoretical description of the energy loss of a filled foam material under mechanical oscillatory deformation. They revealed that the liquid flow plays a major role in the energy loss as it is being forced to go in and out of the foam during a cyclic deformation. Later, Hilyard5 studied impacts on a liquid-filled foam material and, in particular, the contribution of the fluid flow on the impact behavior. As the impact velocity increases, Hilyard observed an increase followed by a decrease in the ratio between the dissipated and stored energy within the elastic, liquid-filled foam. More recently, another study of the contribution of the fluid flow in porous material has been proposed by ref. 6. In this experimental work, they also studied the contribution of the fluid to the elastic response of a liquid-filled foam cylinder under a slow compressive strain rate. They showed that in the elastic regime, the liquid flows through the porous material and induces an additional pressure, which follows Darcy’s law. However, the energy dissipation due to the internal flow of the viscous fluid within the porous medium has not yet been investigated. In the experiments we report here, we study the impacts of fluid-filled poroelastic spheres and find good agreement with Hertz contact theory for small deformations of the sphere upon impact on a solid surface: the elastic energy stored during the impact is not affected by the presence of the internal fluid. Still, the restitution coefficient strongly depends on the impact velocity. This allows the use of a simple approach in which porous flow within the sphere is driven by the gradients in elastic pressure predicted by Hertz’s theory, allowing to calculate analytically the effect of the poroelasticity on the restitution coefficient of the spheres impacting solid substrates. This theory is then compared to experiments, and very good agreement is found.

In 1881, Heinrich Hertz published his pioneering work7,8 on the contact of two elastic ellipsoids. He gave an analytical expression for the force on a deformed elastic sphere in contact with a rigid surface (see Supplementary Note 1 for more details). In elastic collisions, the initial kinetic energy (({E}_{{{rm{k,0}}}} sim m{{V}_{0}}^{2})) is entirely restored as kinetic energy in the rebound (({E}_{{{rm{k,r}}}} sim m{{V}_{{{rm{R}}}}}^{2})). This is so if there is no dissipation of energy during the impact, giving rise to a restitution coefficient e = 1. The coefficient of restitution e is defined as the ratio between the rebound and the impact velocities VR and V0, respectively. We prefer to focus on the square of the coefficient of restitution, which corresponds to the relative kinetic energy left after the impact.

In reality, collisions are inelastic, and a fraction of the incident energy is dissipated (Ek,r = Ek,0 − Ed) during impact9,10, so that e2 < 1. The kinetic energy of a dry ball impacting a surface can be dissipated through different mechanisms, including plastic deformation9,11,12,13, frictional contacts due to the surface roughness10, propagation of elastic waves14,15, and adhesive forces16. The ratio between the energy dissipated from the solid phase and the kinetic energy before the impact, denoted ({alpha }_{{{rm{dry}}}}=frac{{E}_{{{rm{d,dry}}}}}{{E}_{{{rm{k,0}}}}}), is not investigated here but is taken into account by defining eref as follows :

When a liquid film covers the surface of the ball, additional dissipative effects are involved in the bouncing behavior.

In 1997, Johnson, Kendall, and Roberts17 modified the Hertz theory by incorporating the effect of adhesion. This is known as the JKR theory and is of interest for understanding aggregation problems or pull-off forces between two bodies. When the substrate and/or the ball’s surface is wet, the presence of a liquid film between the ball and the substrate affects the rebound of the ball as energy is required to overcome capillary forces during separation of the ball from the substrate. An expression for the role of the capillary adhesion force between two spheres has been proposed by ref.18. This expression involves an adhesion force proportional to cos(θ), with θ being the contact angle of the liquid bridge in contact with the surface. During the approach phase, we can assume that the contact angle is around 90° as the liquid film spreads over the surface, so the capillary force mainly plays a role during the rebound phase. Therefore, the energy cost needed to separate the ball from the surface is equivalent to the energy needed to create two new liquid-air interfaces is ({E}_{gamma } sim gamma {{D}_{max }}^{2}) 17, where γ is the surface tension of the liquid-air interface and ({D}_{max }) is the maximum contact diameter of the ball with the substrate. If we assume that adhesion forces only affect the rebound phase and that ({D}_{max }) can be estimated using the Hertz model, the coefficient of restitution e is found from the equation of energy conservation after taking into account the energetic contribution of the capillary adhesion:

In Eq. (3), R and m are respectively the radius and the mass of the ball and (k=16sqrt{R}{E}_{0}/15left(1-{nu }^{2}right)) is a constant that depends on the elastic modulus E0 and the Poisson ratio ν of the ball. For convenience, we rewrite Eq. (3) as:

Below we shall call Eq. (4) the “capillary adhesion” dissipation model. Details of the model are given in Supplementary Note 2.

During the contact of the wet ball with the surface, the thin liquid film formed between the surface and the ball is squeezed, resulting in additional viscous losses. This situation is known as an elastohydrodynamic collision19,20,21,22,23. Based on lubrication theory, Davis et al.23 proposed a simple model to account for the dissipation in the viscous film. They showed that the rebound of the sphere depends on the Stokes number St = mV0/(6πηR2), where η is the viscosity of the liquid film, and that no rebound occurs below a critical Stokes number Stc. They found that e is given by

The critical Stokes number Stc is defined as ({{{rm{St}}}}_{{{rm{c}}}}=frac{{x}_{0}}{{x}_{{{rm{r}}}}}) with x0, the initial film thickness, and xr, the minimum distance between the solid sphere and the surface during the contact, which depends on the liquid film properties (thickness, viscosity) and the elastic properties of the ball19. Details of the model are given in Supplementary Note 3. We shall henceforth call Eq. (5) the “viscous film” dissipation model. For convenience, we rewrite it as:

The total effect of capillary adhesion plus viscous film dissipation is obtained by combining Eqs. (4) and (6).

The impacts of wet spheres have been studied previously17,18,19,23,24,25, and different mechanisms have been proposed to explain the bouncing behavior of such spheres. In addition to previously well-studied dissipation mechanisms such as capillary adhesion11,25 and thin-film viscous dissipation19,23, we propose a new model for the dissipation due to the coupling between the porous ball’s deformation and internal flow within the poro-elastic material.

The third dissipation model we shall consider is a “poroelastic” model. If the ball is porous and fluid-filled, its deformation during impact will induce pressure gradients that drive internal porous flow, producing additional viscous dissipation26,27,28. The derivation of this model is given below in the Results section. As we shall show, poroelastic dissipation is important and even dominant in some cases.

Results

Rebound Experiment

Our experiments make use of different balls, some of which are porous and can be filled with liquids of different viscosities. As a dry reference, we use so-called “bouncy balls”, commercial rubber balls with restitution coefficients close to unity. We use two different types of wet balls. The first are hydrogel spheres, which are composed of a water-swollen polymer network and which also have high restitution coefficients. Hydrogels are materials that have generated much recent interest for applications ranging from agriculture (water storage in the soil) to the biomedical field29,30, where materials that can undergo strong deformations without cracking are needed31. Second, we use commercial foam balls made of polyurethane. Such balls deform readily upon impact, making them good candidates for investigating impacts of soft porous balls. Compared to hydrogels, our foam balls are larger and sponge-like, allowing them to be filled with liquids of different viscosities. The solid surface used is a 1.5 cm thick transparent polycarbonate plate.

To quantify the elastic deformation of the three types of balls during impact, we measured the contact diameter as a function of time using a fast camera placed below the transparent solid surface (see Supplementary Note 5). To compare these data with the predictions of the Hertz model, we need to know the effective elastic modulus E* = E0/(1 − ν2), where E0 is Young’s modulus and ν is Poisson’s ratio. We measured this modulus by placing the balls under compression in a rheometer (Supplementary Note 1). We found E* = 2 MPa for the rubber ball, 45 kPa for the hydrogel, and 130 kPa for the foam balls independent of the filling liquid. In Supplementary Note 1, we demonstrate that the elastic deformation during impact of all three types of balls is well described by the Hertz contact model. Note that in our experiments, we use relatively low impact velocities so that the deformation of the balls is small and can be described by the Hertz model. For higher impact velocities, the deformation of the soft hydrogel balls or the foam balls becomes too important, and the Hertz contact theory breaks down1,2. In this large deformation regime, the coefficient of restitution shows a strong decrease for both the hydrogel and the foam balls (see Supplementary Note 4); this effect has been previously studied for hydrogel spheres1,2.

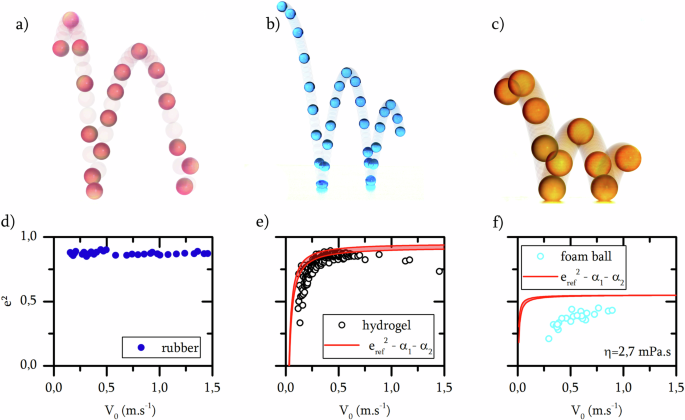

In Fig. 1, the rebound of our three different balls (rubber, hydrogel, and foam) is illustrated as a series of superimposed snapshots. The rubber ball rebounds almost to its initial height, the fluid-filled foam ball rebounds to only about half its initial height after the first bounce, and the hydrogel ball is intermediate.

Bouncing of (a) a rubber ball (R = 21 mm, frame rate 50 fps), (b) a hydrogel ball (R = 7 mm, 280 fps), and (c) a dry foam ball (R = 34 mm, 500 fps). Each panel is a superposition of images recorded with a fast camera. Some of these images are highlighted to illustrate the trajectory. d Coefficient of restitution of the rubber ball (dark blue dots). e Coefficient of restitution of the hydrogel ball (black circles) compared with the model of Eq. (7) with 6 < Stc < 10 and 0.92 < eref < 0.97. f Coefficient of restitution of a foam ball filled with water-glycerol mixture I (cyan circles), compared with the model of Eq. (7) with eref = 0.55 corresponding to the dry case and 6 < Stc < 10. Liquid properties are given in Supplementary Note 7. Stc is the critical Stokes number and eref the reference coefficient of restitution.

Figure 1d–f show how the coefficient of restitution e2 varies as a function of the impact velocity V0 for our three types of balls. For rubber balls, e2 is independent of V0 (Fig. 1d). However, e2 varies strongly as a function of V0 for the other two types of balls. For hydrogel balls, e2 increases rapidly with increasing V0 up to 0.9 m s−1 and then decreases slowly thereafter (Fig. 1e). For the foam balls saturated with a water-glycerol mixture, e2 is a monotonically increasing function of V0 (Fig. 1e) in the range of velocities used in this study. For higher impact velocities, the assumption of the Hertz model of small deformations of the sphere is no longer valid2,32. In this study, we only consider small impact velocities: the indentation of the sphere h remains small compared to the radius of the ball h/R < < 1 so that the bouncing behavior is well captured by the Hertz model.

It may seem counterintuitive that increasing the impact speed of the ball results in higher restitution. The coefficient of restitution is defined as the ratio ({e}^{2}=frac{{E}_{{{rm{k}}}}-{E}_{{{rm{d}}}}}{{E}_{{{rm{k}}}}}). The absolute value of energy dissipated from capillary adhesion and viscous dissipation in the liquid film Ed increases with the velocity, but the relative dissipated energy (frac{{E}_{{{rm{d}}}}}{{E}_{{{rm{k,0}}}}}) decreases with the impact velocity. The observed variation of the coefficient of restitution for the hydrogel balls can be explained reasonably well by a combination of the capillary adhesion and viscous film dissipation models. The resulting prediction of e2 is indicated by the narrow red regions in (Fig. 1e). Because eref and Stc are not known for the hydrogel spheres, we used ranges of values 0.92 < eref < 0.975 and 6 < Stc < 10. The interval of Stc is chosen based on the assumptions of the maximum and minimum liquid film thickness. The maximum liquid thickness is chosen as x0 = 1 mm, and the minimum thickness is given by the roughness of the surface, which is of the order of 10−6 m33. Although we only consider two mechanisms of energy dissipation, the result of Eq. (7) gives the good trend of the variation of e2 for a large range of velocities.

For the saturated foam ball, the combination of capillary adhesion and viscous film dissipation does not explain the observed restitution coefficients, assuming eref to be that of a dry foam ball (see below) and 6 < Stc < 10. We propose that our observations for foam balls require a third dissipation mechanism associated with porous flow inside the fluid-saturated ball, which has much larger pores than the hydrogel spheres. In the next subsection, we present a new model for this poroelastic dissipation mechanism.

Poroelastic dissipation

The theory of poroelasticity has a long history going back to the work of K. Terzaghi26 and M. Biot27. In this theory, the deformation of the solid elastic matrix is influenced by gradients of interstitial fluid pressure, and the fluid pressure itself evolves with time. The physics of this situation gives rise to a complicated initial/boundary-value problem that would have to be solved numerically. However, in the experiments we report here on deforming poroelastic spheres, we find remarkable agreement with the loading curves and maximum contact diameter predicted by Hertz contact theory. This suggests that we try a simpler approach in which porous flow within the sphere is driven by the gradients in elastic pressure predicted by Hertz’s theory.

The flow in a porous medium is described by Darcy’s law,

where u is the pore-scale percolation velocity, κ is the permeability (m2), η is the fluid viscosity (Pa.s), ϕ is the porosity, and ∇ P is the hydraulic pressure gradient (Pa.m−1). The effective flux of fluid through the medium (volume of fluid per unit surface area per unit time) is the product ϕu. During impact, deformation of the ball around the contact area gives rise to a pressure gradient that drives porous flow. The pressure scales as the Hertzian contact force FHertz divided by the contact area of radius r, or P ~ FHertz/r2. Let δ be the height of the portion of the ball above the contact area in which the pressure gradient is applied (see Supplementary Note 1). We can then rewrite Eq. (8) as

From Hertz contact theory, we have

where (D=3left(1-{nu }^{2}right)/4E), E is Young’s modulus, h is the deformation of the poroelastic ball, and ν is the Poisson’s ratio. Replacing in Eq. (9) the Hertz force and the contact radius and assuming δ ~ h, we have

From ref. 34, the rate of viscous dissipation per unit volume is :

The volume Ω over which the dissipation occurs scales as

From Eqs. (12) and (13), the total rate of viscous dissipation inside the sphere is:

The total dissipation rate over the contact time tc (which includes both the compression and rebound phases) is

ΔE can be estimated as

where we have used the scales for ({h}_{max }) and tc from Hertz contact theory8 and (k=4sqrt{R}/5D). Quantity B is the unknown constant of proportionality.

For convenience and later use, we define a characteristic velocity Vc as

The coefficient of restitution is then

Note that ({alpha }_{{{rm{Poro}}}}propto {V}_{0}^{-7/5}), this is consistent with an increase of the coefficient of restitution with increasing V0. Then, we write the full expression of the coefficient of restitution of wet poroelastic balls, which includes the three different dissipative mechanisms (capillary adhesion, viscous dissipation in the liquid film, and viscous dissipation within the poroelastic material):

Comparison with experiments

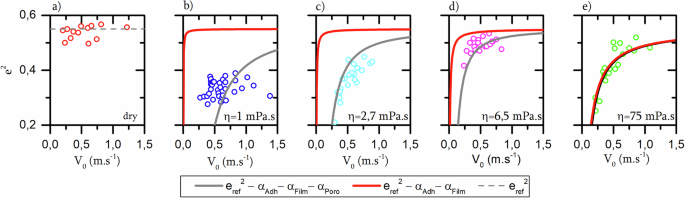

We performed experiments with foam balls saturated with different viscous fluids. Figure 2 shows the measured restitution coefficients e2 as functions of the impact velocity V0 for the different cases. For a dry ball, e2 ≈ 0.55 is nearly constant (Fig. 2a). For balls saturated with water, e2 ≈ 0.3 is also nearly constant, but the data show considerable scatter (Fig. 2b). For balls saturated with water-glycerol mixtures, e2 increases with V0, especially for water-glycerol I (Fig. 2c, d). Finally, for a ball saturated with viscous oil e2 increases strongly with V0. (Fig. 2e).

Foam balls saturated with: a air (red circles), b water (blue circles), c water-glycerol mixture I (cyan circles), d water-glycerol mixture II (pink circles) and e rapeseed oil (green circles). The dry reference restitution coefficient (dotted gray line in a) is ({e}_{{{rm{ref}}}}^{2}=0.55). Also shown in (b–e) are the predictions (red lines) using the Eq. (7) combining the capillary adhesion and viscous film dissipation model with a critical Stokes number Stc = 3.2. Finally, the grey line in (b–e) shows the prediction of the solution of Eq. (19) with a fitting parameter B = 0.05 and Stc = 3.2. The other parameters used in the models are given in Supplementary Note 7.

Also shown in Fig. 2 are the predictions of the viscous film dissipation model (red lines) and the solution of Eq. (19) (gray lines). Calculation of the porous flow model predictions requires an estimate of the permeability, which we determined to be κ ≈ 70 × 10−12 m2 (see Supplementary Note 6). Using this value, we find reasonable agreement with the observed variation of e2 versus impact velocity for balls saturated with water and water-glycerol mixtures (Fig. 2b–d). However, a curious result is found for a ball saturated with rapeseed oil, whose viscosity is sufficiently high that viscous film dissipation alone can explain the measurements (Fig. 2e). Using Stc as the only adjustable parameter, we find that Stc = 3.2 gives the best fit for this case. Because porous flow dissipation diminishes with increasing viscosity, its contribution is too small to cause any observable effect in this case. A partial comparison between the different dissipation mechanisms is shown in the Supplementary Note 3.

The dominance of porous flow dissipation for water- and water/glycerol-saturated foam balls allows us to simplify the presentation of the experimental results for these cases. Figure 3 shows the experimentally determined restitution coefficients plotted against the ratio V0/Vc, where Vc is the characteristic velocity scale given by Eq. (17). Within error due to experimental scatter, the data collapse onto a single master curve. The agreement between our model and the experimental results for fluids of different viscosities, as well as the rescaling of the data onto a master curve, confirm the importance of internal poroelastic flows in dissipating energy due to impacts.

Foam balls saturated with water (blue circles), water-glycerol mixture I (cyan circles), and water-glycerol mixture II (pink circle) rescaled on a single curve using the critical impact velocity Vc given in Eq. (17). The black line is the solution of Eq. (18).

Returning to the case of hydrogel balls, we note that poroelastic dissipation is too small to explain the data. It has already been shown that the permeability of a hydrogel is on the order of κ ~ 10−16 m2 or smaller35,36,37. For such low permeabilities, the contribution of viscous dissipation in the pores is negligible. For low-permeability and very viscous fluids, porous balls simply act as elastic materials.

Conclusion

We have examined the impact behavior of different soft solids on rigid surfaces, including solid rubber balls, hydrogel balls, and dry or liquid-saturated foam balls. While the deformation of such soft solids during impact is well described by Hertz contact theory, their rebound behavior can only be explained by invoking a variety of dissipation mechanisms. For each type of soft solid, we measured the restitution coefficient e2 as a function of the impact velocity V0. For the rubber and dry foam balls, e2 is independent of the impact velocity but less than unity, indicating the presence of “dry” dissipation mechanisms that are beyond the scope of our work. The situation is more complicated for the “wet” cases of hydrogel balls and fluid-saturated foam balls. For these cases, e2 is an increasing function of V0, meaning that more rapidly impacting balls rebound more efficiently. We identified three possible dissipation mechanisms that may explain this behavior: capillary adhesion, dissipation in the viscous film between the ball and the substrate, and internal poroelastic dissipation.

We propose a new model for poroelastic dissipation: this model combines the Hertz model with Darcy’s law and gives rise to a solution for e2, which increases with the impact velocity. We found that the dissipative term is proportional to (frac{kappa }{eta }): a permeable material will let the liquid flow easily through it, which leads to strong dissipation. On the other hand, a high viscosity of the fluid will allow less flow, and almost no energy is dissipated. In contrast with fluid-saturated foam balls, the rebound systematics of hydrogel balls can best be explained by a combination of capillary adhesion and viscous film dissipation, with only a minor contribution from poroelastic dissipation. We believe that this is due to the very low permeability of hydrogel balls, which is 4–5 orders of magnitude smaller than that of the foam balls used. Because the rate of poroelastic dissipation is proportional to the permeability, this contribution to the dissipation can be expected to be small for hydrogel balls compared to the foam balls. The rate of poroelastic dissipation is also inversely proportional to the fluid viscosity, which explains why this dissipation mechanism appears to be negligible for foam balls saturated with viscous rapeseed oil.

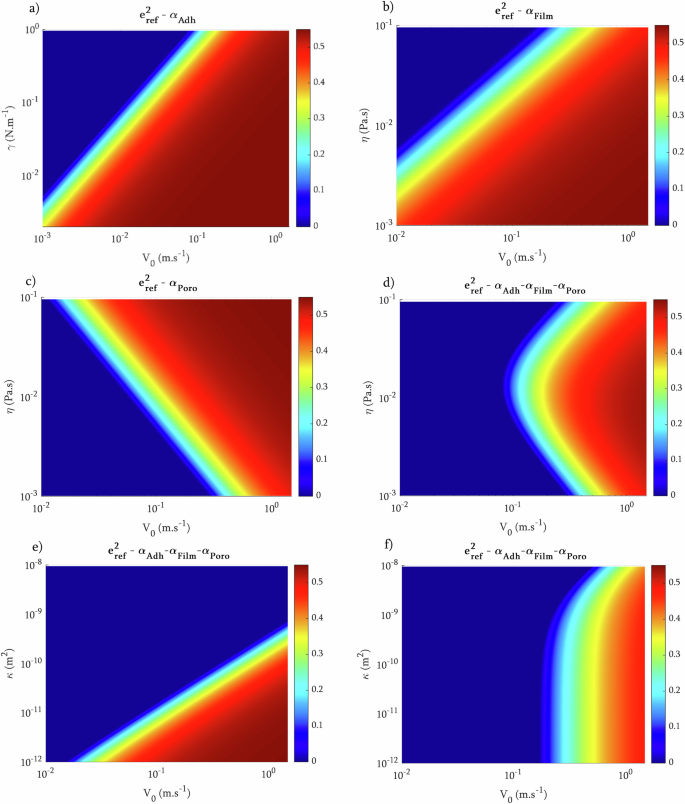

The importance of the three different dissipative mechanisms is illustrated in Fig. 4. We first estimate in Fig. 4a the energy loss due to capillary adhesion, which is found to be effective only for very small velocities and high interfacial tensions. Figure 4b, c show, respectively, the energy loss due to the presence of a viscous film and the poroelastic dissipation as a function of the viscosity of the internal fluid and the velocity. These color maps show that the effect of the viscous film can be observed strongly for the low velocity end and that this effect becomes stronger and effective at even higher velocities as the viscosity of the fluid increases. On the other hand, the dissipation due to the porosity of the material is effective for small viscosities, for which the effect is strong even at higher velocities but decreases as the viscosity increases. The effect for high viscosities is important only at the low-velocity end. We show in Fig. 4d the sum of the different dissipative terms to illustrate the total energy loss for a porous wet ball impacting a dry surface. The most important contributions turn out to be porous dissipation at low viscosities and dissipation due to the presence of a viscous liquid film at high viscosities. To further illustrate the role of the different parameters in setting the restitution coefficient, we plot in Fig. 4e, f the sum of the three dissipation mechanisms in the permeability-velocity space for two different viscosities. For the small viscosity, the effect is more important and is effective for a large velocity range for high values of the permeability. For the larger viscosity, the effect is important mostly for small velocities.

a Solution of dissipation from capillary adhesion (Eq. (3)). b Solution of viscous dissipation in the liquid film (Eq. (5)). c Solution of viscous dissipation within the porous sphere (Eq. (18)). d Solution of the sum of the three dissipative terms. The surface tension is taken as that of pure water γ = 72 mN m−1. The free parameter is fixed as B = 0.05 and the critical Stokes number as Stc = 3.2. Solution of the sum of the three dissipative terms depending on the permeability of the foam ball and for two different viscosities η = 1 mPa.s (e) and η = 100 mPa.s (f). The surface tension γ, the critical Stokes number Stc, and the free parameter B are γ = 72 mN m−1, B = 0.05, and Stc = 3.2.

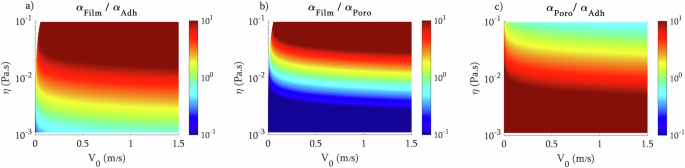

To better illustrate the relative importance of each dissipative term, we show in Fig. 5 colormaps of ratios of the different dissipative terms. Figure 5a shows that dissipation in the viscous film becomes dominant with respect to the adhesion as the viscosity increases. Figure 5b shows that poroelasticity dominates at the lower viscosity end with respect to the film dissipation, which takes over only at high enough viscosities. The poroelastic dissipation is, however, generally larger than dissipation due to capillary adhesion except at sufficiently high viscosities. Our model is, however, only valid for small deformations and cannot explain the decrease of e2 with increasing V0 for hydrogel balls when V0 > 1 m s−1 (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Note 4).

a (frac{{alpha }_{{{rm{Film}}}}}{{alpha }_{{{rm{Adh}}}}}), (b) (frac{{alpha }_{{{rm{Film}}}}}{{alpha }_{{{rm{Poro}}}}}), and (c) (frac{{alpha }_{{{rm{Poro}}}}}{{alpha }_{{{rm{Adh}}}}}). The two parameters are set as B = 0.05 and Stc = 3.2. Surface tension is fixed as γ = 72 mN m−1, and physical properties of the porous foam ball are given in Supplementary Note 7.

Overall, this study provides insights into the complexity of impacts of liquid-filled soft solids, highlighting the importance of the presence of liquid within the porous structure of the solids in dissipating impact energy. This last dissipation mechanism and the closed theoretical expression for its effect on the restitution coefficient open the way to designing and engineering a new generation of shock absorbers, cushions, and armor. An example of such an application is Dawson et al.38 study of an open-cell foam impregnated with a shear-thickening non-Newtonian fluid.

Methods

Experimental measurements of the foam and hydrogel balls

The spheres used in the experiments are made of either rubber, hydrogel, or foam (see Supplementary Note 5). The rubber balls were bought from Intertoys and are made of synthetic rubber. Hydrogel balls are originally small dry beads of polymer (polyacrylamide) bought from Educational Innovations (GM 710). These dry beads are immersed in a solution of salty water (pure Milli-Q Water with a concentration of 0.6 g L−1 of NaCl) and left to swell for 24 h. During this time, they reach an average diameter of D0 ≈ 15 mm with a liquid volume fraction of ϕ = 0.98 and a constant mass of ~m = 2.8 g. The foam balls used are commercial tennis foam balls purchased from Intersport (Ref: Pro Touch 412174 6TP) and are made of polyurethane. The foam balls have a diameter D0 = 68 mm and exhibit sponge-like behavior: Water or other liquids can be absorbed and released under pressure.

The mechanical responses of the rubber, hydrogel, and foam balls were measured using a rheometer in compression mode.

All rubber, foam and hydrogel ball properties are reported in Supplementary Note 7. The properties of the liquids used to saturate the foam balls in the experiments are also given in Supplementary Note 7.

Before each experiment, we measured the mass of the saturated ball. The mass of the filled foam ball before each experiment is kept constant at ~m ≈ 122 ± 2 g. Once the mass is determined, the ball is dropped by hand from a certain height and bounces multiple times. The experimental setup is shown in Supplementary Note 5.

When the hydrogel ball is removed from the water, it is fully covered with a thin film of water. Before being dropped, the excess water is removed with a clean paper tissue. However, due to the porous nature of the gel, a thin film of water remains on the surface of the ball. The hydrogel ball is then dropped by hand from different heights. Two high-speed cameras (Phantom V641) are used simultaneously to capture the impact from the bottom and the side. The surface used is a 1.5 cm thick transparent polycarbonate plate. This plate was solidly fixed on top of a granite table, leaving a space between the table and the plate where a mirror was inserted at 45° to visualize the impact from below. Camera frame rates range from 2000 to 10,000 fps for the side views and from 70,000 to 80,000 fps for the bottom view. After each impact, the hydrogel ball is immediately put back into water to prevent evaporation.

The foam ball is first entirely immersed by hand in a pool of liquid and compressed manually to expel the air trapped inside. Different liquids are used to fill the ball: water, water-glycerol mixtures, and rapeseed oil. After the pressure is released, liquid is sucked into the ball. Once the ball is back to its spherical form, it is removed from the liquid pool and is cleaned using tissues to remove the excess liquid present on its surface.

Responses