Incompletely closed HIV-1CH040 envelope glycoproteins resist broadly neutralizing antibodies while mediating efficient HIV-1 entry

Introduction

Infection with human immunodeficiency virus type I (HIV-1) leads to a gradual decrease in CD4 T cells and, without treatment, to an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in most infected individuals1. HIV-1 is most frequently transmitted to uninfected individuals during exposure to mucosal surfaces2. These sites are a selective bottleneck for successful transmissions and only a subset of HIV-1 strains can cross the mucosal barrier to establish a new infection. Studies of very early HIV-1 infections identified post-transmission early replicating viral strains, termed Transmitted/Founders (T/F)2,3,4. T/F strains are resistant to interferons α and β and typically express 1.9-fold higher levels of HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins (Envs) on their surface relative to other, chronic HIV-1 strains3. During viral replication, HIV-1 Envs interact with the cellular CD4 receptor and CXCR4/CCR5 coreceptor to facilitate viral entry5,6,7,8,9. Since they are the sole viral proteins on HIV-1 surface, HIV-1 Envs are the only target of antibodies that can neutralize viral infection10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

HIV-1 Envs are assembled as a trimer on HIV-1 surface with each of the 3 units composed of a surface gp120 subunit non-covalently associated with a transmembrane gp41 subunit, which anchors the Env trimer into the virion membrane17,18. The two glycoproteins in each unit work in concert within the trimeric context to mediate viral entry: gp120 mediates receptor binding and, subsequently, gp41 facilitates viral and cellular membrane fusion17,18,19,20,21,22. The two separate activities are coupled and regulated by the metastability of HIV-1 Envs23,24; binding to the CD4 and CCR5/CXCR4 receptors triggers large structural rearrangements in HIV-1 Envs that facilitate and lead to gp41-mediated membrane fusion19,25. Env transitions to a stable conformation release the energy that is stored in the metastable conformation and can be used to support HIV-1 entry24.

Broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) target highly conserved regions of HIV-1 Envs and neutralize a wide diversity of HIV-1 strains12,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. bnAbs are developed in a subset of people living with HIV (PLWH) after a long period of chronic HIV-1 infection35; they are typically enriched in somatic hypermutations and contain a long complementary region 3 (CDR3) of the heavy chain that allows bnAbs to penetrate the glycan shield and interact with underlying conserved Env residues36. Structural studies as well as binding and neutralization assays defined at least six sites of Env vulnerability that can be targeted by bnAbs: CD4-binding site (CD4bs), V1/V2 loop, V3-glycan, gp120–gp41 interface, gp41 fusion peptide, and the membrane-proximal external region (MPER) of gp4113,27,28,29. Some bnAbs can selectively neutralize specific Env conformations of primary HIV-1 strains23,37. Most CD4bs and V1/V2 bnAbs preferentially neutralize the closed Env conformation of primary HIV-1 strains, whereas bnAbs targeting the gp41 MPER neutralize more efficiently the open Env conformation23,38,39,40. Several bnAbs, including a few that target the V3-glycan, can recognize equally well closed and open Env conformations. However, glycan-targeting bnAbs are intrinsically less broad than those that target Env amino acids because of heterogeneous glycosylation patterns even within single cells. Ongoing and completed clinical trials have tested the effects of bnAb administration on HIV-1 treatment and prevention, including the first in-human VRC01-mediated prevention trial (AMP; HVTN 704)41, and provided important guidance to future development of bnAbs. Nevertheless, these studies also provide evidence for distinct mechanisms of HIV-1 resistance to bnAbs in vivo42,43,44,45.

HIV-1 can escape bnAb neutralization by introducing one or more changes in the amino acid sequence of HIV-1 Envs. Direct changes to the antibody epitope are frequent but highly conserved epitopes may not tolerate significant changes and, thus, changes that confer bnAb resistance are sometimes distant from the bnAb binding site, exerting allosteric effects to interfere with epitope access16,23,38. Envs changes could potentially affect both replication capability and bnAb neutralization efficacy. Some reports documented decreased replication fitness of changes that increased resistance to nAbs as well as identified growth-enhancing mutations46 but comprehensive knowledge about the relationship between these two properties is still lacking. Moreover, some primary HIV-1 strains, including T/Fs, exhibit pre-existing resistance to several bnAbs even without prior interactions with these bnAbs. This pattern of resistance could be related to multiple parameters, including the continuous development of both weakly neutralizing and strain-specific antibodies in PLWH, which could shape the evolution of HIV-1 intra-host quasispecies and exert pressure to adopt specific Env conformations. Moreover, the several studies have provided evidence for an overall drift of primary HIV-1 strains toward increased bnAb resistance over time47,48. Here we investigated the relationship between high bnAb-resistance of Envs of a T/F strain (CH040), which has been previously identified2, and efficient viral entry. We also studied how rationally-design engineered changes alter bnAb sensitivity and entry effciency compatibility. Simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) CH040 has been previously reported to mediate high level of replication in rhesus macaques49 and we further monitored the kinetics of SHIV CH040 spread in lymphocytes of pig-tailed macaques (PtMs).

Results and discussion

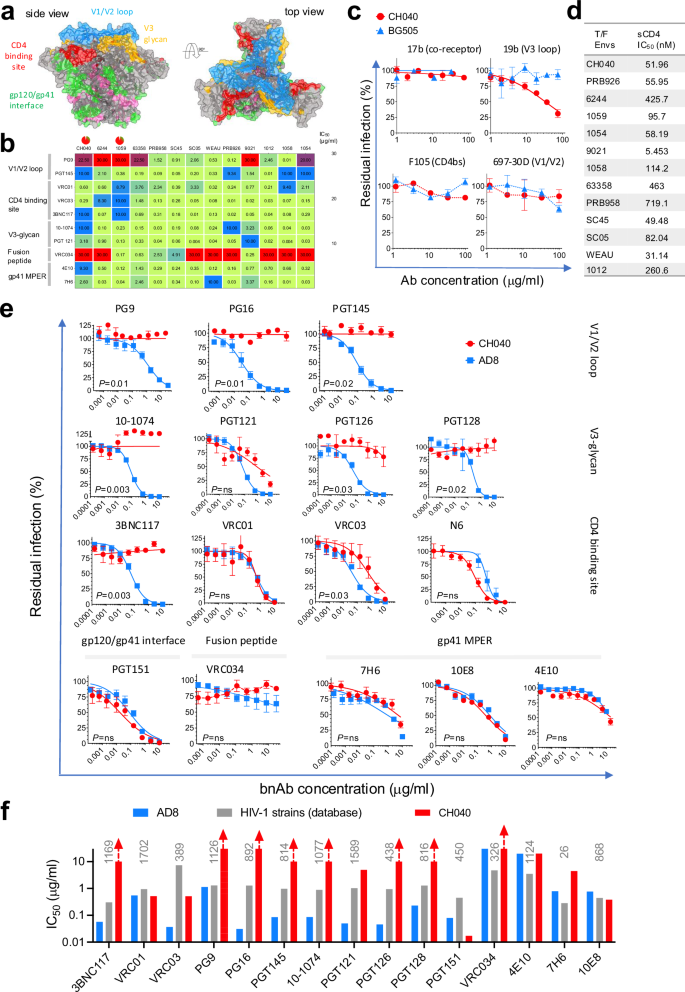

We have recently evaluated Env conformational flexibility and how in vivo evolution altered Env conformation and sensitivity to bnAbs50. We reported that Envs of most primary HIV-1 strains prefer to adopt a tightly closed Env conformation but Envs of some strains are incompletely closed based on exposure of their internal Env epitopes to antibodies24,50. Thus, incompletely closed Envs are weakly-moderately sensitive to antibodies that target internal Env epitopes, soluble CD4 (sCD4), and cold. During our previous screen of several published2 T/F Envs for their sensitivity to a small panel of different bnAbs we identified a unique profile of CH040 Envs50. In contrast to most HIV-1 Envs, CH040 Envs are incompletely closed and moderately sensitive to sCD4, cold and 19b antibody, which targets the V3 loop of gp120 – a region that is typically occluded in Envs of most primary HIV-1 strains (Fig.1)50. In addition, CH040 Envs are resistant to several bnAbs including PG9 and PGT145 (targeting the gp120 V1/V2 loop); 10-1074 and PGT121 (targeting the gp120 V3-glycan), 3BNC117 (targeting the CD4bs), VRC034 (targeting the gp120/gp41 interface); and 7H6, and 4E10 (targeting gp41 MPER). Here we expanded our original study and measured the sensitivity of viruses pseudotyped with CH040 Envs, and as a control with AD8 Envs, to a large panel of bnAbs (Fig. 1). We included in this panel bnAbs targeting the following Env vulnerability sites (Fig. 1): V1/V2 loop (PG9, PG16 and PGT145); V3-glycan (10-1074, PGT121, PGT126 and PGT128), CD4bs (3BNC117, VRC01, VRC03), gp120/gp41 interface (PGT151), gp41 fusion peptide (VRC034), and gp41 MPER (10E8, 7H6, and 4E10). We did not detect any significant effect of V1/V2 loop bnAbs on CH040 Env-mediated entry up to a concentration of 10 μg/ml. Similarly, CH040 pseudoviruses were highly resistant to neutralization effects of 10-1074 and PGT128 and showed only weak decrease in infectivity when tested against high concentrations of PGT121 and PGT126. CH040 sensitivity to the CD4bs bnAbs varied; 3BNC117 had no effect on HIV-1 entry but VRC01, VRC03, and N6 efficiently neutralized CH040 entry into target cells. The gp120-gp41 interface bnAb PGT151 efficiently neutralized CH040 pseudoviruses but VRC034, which target the fusion peptide and was reported to exhibit only limited breadth, was completely ineffective up to 30 μg/ml. All gp41 MPER bnAbs neutralized CH040 Env-mediated entry as efficient as they neutralized the control AD8 Env-mediated entry. To confirm high bnAb resistance of CH040 relative to the complete viral population, we compared the sensitivity of CH040 Envs to different bnAbs to the average sensitivity of other HIV-1 strains to these bnAbs using neutralization data that are available in the HIV-1 databases [Fig. 1f; between 26 and 1589 strains (HIResist; https://hiresist.umn.edu/)51 and (Los Alamos National Laboratory HIV-1 database; www.hiv.lanl.gov)52; Supplementary Data 1]. Average neutralization (geometric mean of IC50s) of diverse HIV-1 strains by 3BNC117 (CD4bs); PG9, PG16, and PGT145 (V1/V2 loop); 10-1074, and PGT126 (V3-glycan); and VRC034 (fusion peptide) ranged from 0.3 μg/ml for 3BNC117 to 4.7 μg/ml for VRC034 and was typically several orders of magnitude more potent than the neutralization of CH040 pseudoviruses, which was completely resistant up to 10 μg/ml concentrations of these bnAbs. CH040 pseudoviruses also showed higher resistance to PGT121 than the average of HIV-1 strains. In contrast, CH040 sensitivity to the other bnAbs tested was comparable to the average sensitivity of HIV-1 strains and CH040 was significantly more sensitive to PGT151 than the average of other HIV-1 strains.

We measured the sensitivity of viruses pseudotyped with HIV-1CH040 or, as control, HIV-1AD8 Envs to bnAbs targeting Env vulnerability sites. a Sites of HIV-1 Env vulnerability mapped on available cryo-EM structure (adapted from Jeffy et al. mBio 2024). Residues labeled in pink are part of the gp120-gp41 interface that are not targeted by bnAbs. b Sensitivity of different T/F Envs to bnAbs. c, d Sensitivity of CH040 Env-mediated entry to antibodies that recognize internal Env epitopes (c) and to sCD4 (d). Panels b–d were adapted from Parthasarathy et al. Nat Commun 2024. e Effects of increasing concentrations of different bnAbs on viral entry mediated by HIV-1CH040 or the control HIV-1AD8 Envs (some or the raw data used to make the plots were taken from experiments reported by Parthasarathy et al. Nat Commun 2024). f Comparison of the sensitivity of HIV-1CH040 Envs and the average sensitivity of between 26 and 1589 different Envs to different bnAbs. We calculated average sensitivity of different Envs using available data in HIV-1 databases [(HIResist; https://hiresist.umn.edu/) and (Los Alamos National Laboratory Pathogen Database; www.hiv.lanl.gov)]. Numbers in gray are the number of Envs used for each analysis (detailed data analysis is provided in Supplementary Data 1).

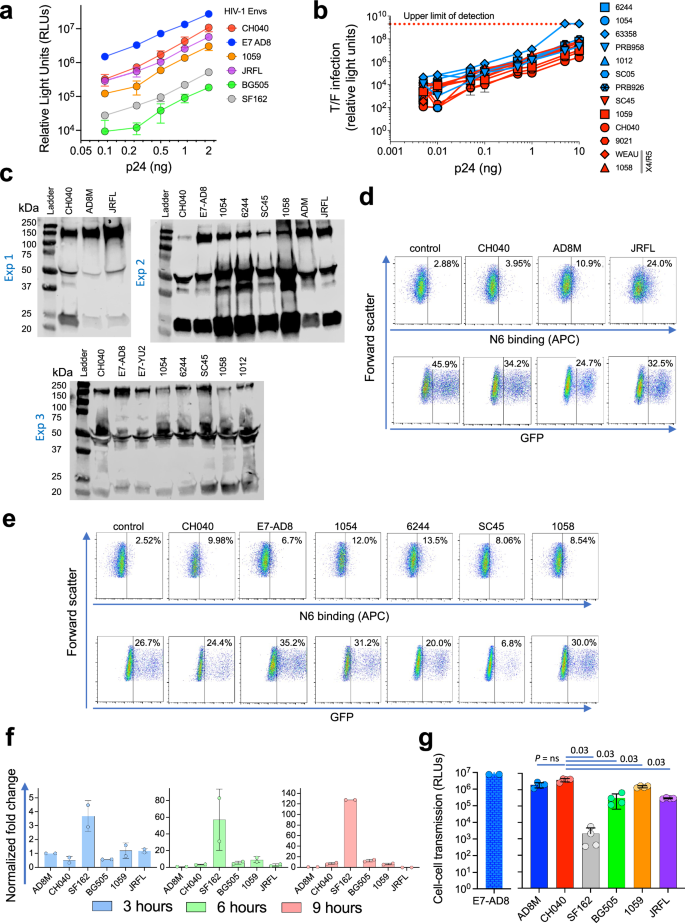

To study the effects of CH040 Env resistance to bnAbs on efficient HIV-1 entry we compared the infectivity of recombinant luciferase-expressing viruses that were pseudotyped with CH040 Envs or, as reference, Envs of other HIV-1 strains (Fig. 2). We tittered the different pseudoviruses on highly sensitive Cf2-Th/CD4+CCR5+ target cells using equal amounts of pseudoviruses based on p24 content of each virus preparation. Viruses pseudotyped with CH040 Envs exhibited comparable levels of infectivity to other primary and lab-adapted pseudoviruses (Fig. 2a). Of note, entry mediated by viruses pseudotyped with CH040 Env was as efficient as the entry of viruses pseudotyped with AD8M and JRFL Envs, which were expressed from codon-optimized env genes. Both Envs were originally isolated from tissues of PLWH (with HIV-1AD8 isolated after minimal passaged in monocytes-derived macrophages)53, exhibit robust infectivity, and have been used extensively in numerous studies. We also have recently shown that entry mediated by CH040 Envs was comparable to the entry mediated by 12 other T/F Envs (Fig. 2b)50. Moreover, CH040-mediated entry was more efficient than entry mediated by other primary Envs that were highly sensitive to most bnAbs, such as HIV-1BG505 Envs (Fig. 2a). Levels of CH040 Envs on pseudoviruses and on surface of transfected 293T cells (Fig. 2c, d) was lower than the level of AD8M and JRFL Envs, which were expressed from codon-optimized env genes, but comparable to the level other chronic and T/F Envs. We tested the ability of CH040 Envs to mediate cell-cell fusion using the well-established TZM-bl cells (Fig. 2f). In this system 293T are transiently co-expressing specific Envs and HIV-1 Tat, and they are then co-cultured with TZM-bl cells for 3–9 h. Efficient cell-cell fusion allows HIV-1 Tat to translocate from the 293T cells to the TZM-bl cells and activate firefly luciferase transcription from the viral LTR promoter that is already integrated into the genome of TZM-bl cells. Cell-cell fusion efficiency mediated by CH040 Envs was comparable to the cell-cell fusion of Envs of primary strains (AD8 and JRFL) and T/F (BG505 and 1059). Notably, cell-cell fusion mediated by the lab-adapted SF162 Envs was significantly higher than cell-cell fusion mediated by Envs of all other primary strains tested. In addition to the typical route of free-virus infection, HIV-1 can replicate by cell-cell transmission between cells. This mode/route of transmission is significantly more efficient than free-virus infection and has substantial implications for HIV-1 transmission, resistance to anti-retroviral drugs and escape from bnAbs42,54,55,56. We have recently developed an ultrasensitive assay to accurately measure HIV-1 cell-cell transmission56 and next used this system to measure transmission between T cells mediated by CH040 Envs and, for comparison, transmission mediated by other HIV-1 Envs (Fig. 2g). Cell-cell transmission mediated by CH040 Envs was comparable and even slightly more efficient than the cell-cell transmission mediated by Env of most other primary strains; in particular, CH040 (and other primary Envs)-mediated transmission was significantly more efficient than the cell-cell transmission mediated by SF162 Envs.

a Relationship between number of pseudovirus particles (assessed by amount of p24) and viral entry into Cf2-Th/CD4 + CCR5+ target cells mediated by viruses pseudotyped with HIV-1CH040 or indicated HIV-1 Envs. b Similar to (a) but for 13 T/F Envs, including CH040 Envs (adapted from Parthasarathy et al. Nat Commun 2024). c Western blot of viruses pseudotyoed with different HIV-1 Envs. ad8m env gene contains a codon optimized HIV-1AD8 gp120 sequence and a native gp41sequence; jrfl env gene was codon-optimized; e7-ad8 and e7-yu2 env genes contain a native sequence of ad8 / yu2 env with a C-terminal sequence of NL-43 gp41. All other Envs are expressed from native T/F env sequences. Blots of three independent experiments are shown. d–e Flow cytometric analysis of Env expression on the surface of 293T cells for the specified Envs. f Cell–cell fusion kinetics of different Envs during 3–9 h. g Cell–cell transmission mediated by viruses pseudotyped with HIV-1CH040 or indicated HIV-1 Envs. Results are representative (a–e) or average (f) of 2 independent experiments, each performed in at least two replicates. Results in panel (g) are the average of four technical replicates.

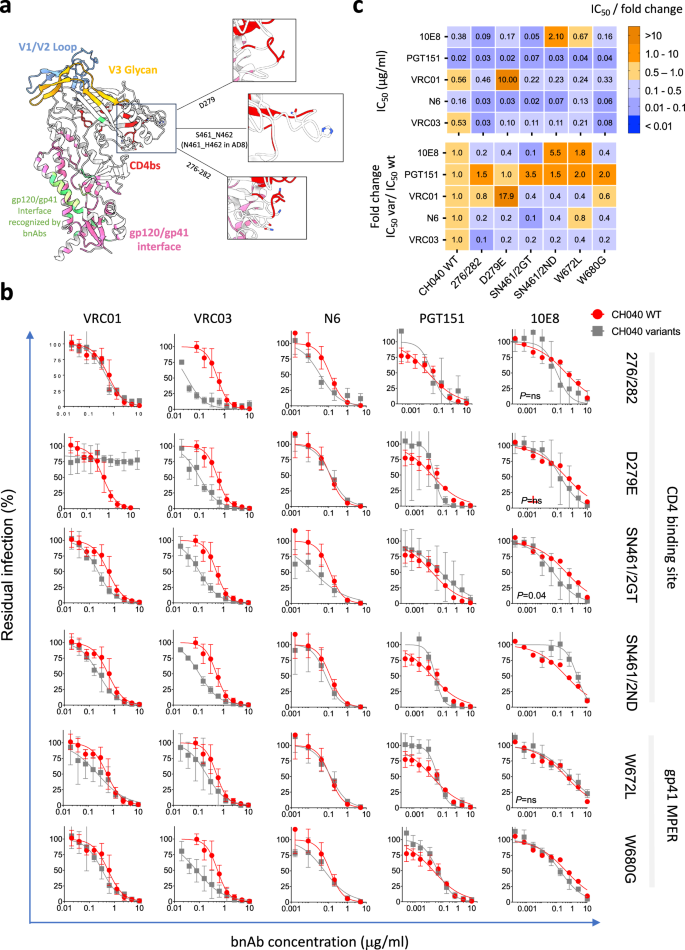

As viruses pseudotyped with CH040 Envs were still sensitive to several bnAbs (e.g., VRC01), we next rationally designed and introduced amino acid changes aimed to disrupt the epitopes of actively neutralizing bnAbs, and then tested the effects of these changes on bnAb sensitivity and viral entry compatibility. We first selected putative epitopes of the CD4bs bnAb since CH040 Envs were highly sensitive to VRC01, VRC03, and N6; we focused on Env residues 276-282 (loop D), and 461-462 (V5) that mapped to the C2 and V5 regions of gp120 (Fig. 3a) and have been shown to be important for CD4bs bnAb-Env interactions.18,27,31, We introduced changes in these residues that have been previously associated with resistance to CD4bs bnAbs, when sequences of sensitive and resistant Envs were compared27,52. In addition, we changed amino acids of the putative gp41 MPER epitopes as CH040 exhibited only moderate resistance to the MPER-targeting bnAb 7H6. Specifically, we introduced separately two changes in gp41: W672L and W680G; both changes were previously associated with the resistance of HIV-1X2088 Envs to the MPER-targeting bnAb 10E832.

a We mapped the amino acid changes introduced in gp120 CD4bs on an available cryo-EM structure of HIV-1AD8 Envs (protein data base (pdb) ID: 8FAD). b Sensitivity of the specified CH040 Env variants to bnAbs. The specific Env changes and their related domains are indicated on the right. c Top—summary matrix of IC50 calculated from the dose–response curves in panel (b); bottom – fold change in IC50 of CH040 Env variants compared to the IC50 of WT CH040 Envs. Color code is identical for the top and bottom matrixes of (c) and is shown on the right.

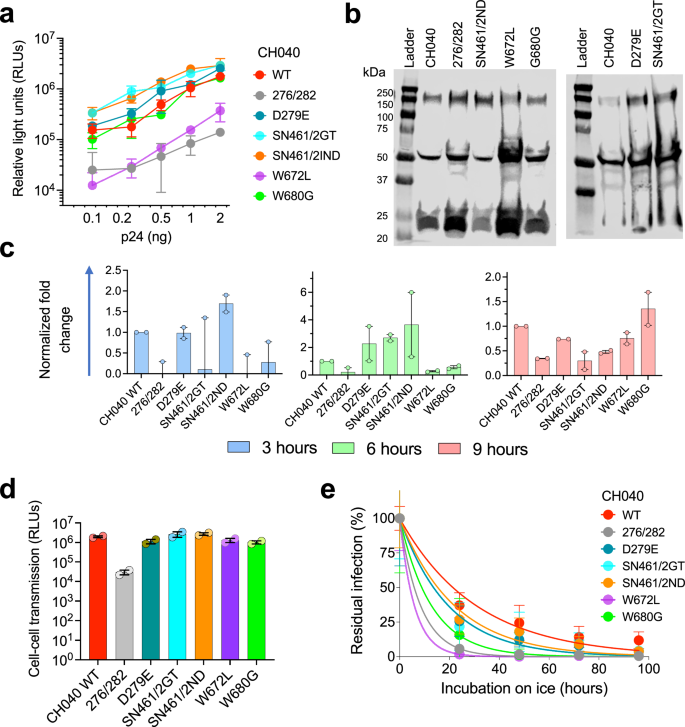

A single amino acid change N279E resulted in complete resistance to VRC01 but not to VRC03 or N6 and this change did not significantly alter viral sensitivity to gp41 MPER and PGT151 bnAbs. Overall, we observed only minimal effects of most engineered changes on the sensitivity to almost all tested bnAbs. Thus, this small group of changes did not appear to alter the recognition of highly conserved set of residues in the context of CH040 Envs by these bnAbs. Unexpectedly, we observed an increased sensitivity of some of these engineered CH040 Env variants to specific bnAbs (e.g., CH040 276/282 sensitivity to VRC01 and VRC03), suggesting that the original target epitope in CH040 WT may not be optimal. In addition, we observed an increased resistance phenotype of CH040 Envs carrying the double change S461N + N462D to 10E8 bnAb, which binds the gp41. Thus, as we have previously documented23,38,39, metastability of HIV-1 Env trimer can lead to allosteric effects when specific amino acids are changed and this, in turn, can alter bnAb sensitivity. We next studied the effect of disrupting the bnAb epitopes in the engineered variants of CH040 Envs on virus infectivity, cell–cell fusion, and cell–cell transmission (Fig. 4). Most changes were well tolerated and infectivity of 4 out of 6 CH040 Envs with engineered changes was comparable to the infectivity of WT CH040 Envs. Changes at position 672, which is close to the viral membrane, and simultaneous, multiple changes in the C2 region of gp120 (276/282) were more deleterious and resulted in an approximately one order magnitude reduction of viral infectivity. The two CH040 variants (carrying the W672L and 276/282 changes) also exhibited a delay in cell–cell fusion, although all tested Envs mediated a reasonable level of cell–cell fusion after 9 h of incubation (Fig. 4c). We next tested cell–cell transmission mediated by all CH040 variants. We detected an efficient cell-cell transmission, which was comparable to CH040 WT Envs, for all variants tested except for the 276/282 CH040 variant that was ~2 orders of magnitude less efficient than wild type. We and others have previously shown an association of hypersensitivity of HIV-1 Envs to cold and more open Env conformations (partially open or fully open), likely because of exposure of cold-sensitive Env elements during spontaneous sampling of downstream conformations39,57,58. To assess such potential changes, we measured Envs sensitivity to cold of all CH040 engineered variants and detected an increase in cold sensitivity of all variants. The W672L change in CH040 Envs resulted in extreme instability on ice, and it was almost completely inactivated after 20-h incubation. Other amino acid changes led to more tolerable phenotype but substantially higher sensitivity to cold relative to CH040 WT Envs. Some of these changes resulted in increased sensitivity to antibodies that recognize internal Env epitopes (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Relationship between number of pseudovirus particles (assessed by amount of p24) and viral entry into Cf2-Th/CD4 + CCR5+ target cells mediated by viruses pseudotyped with WT HIV-1CH040 or indicated engineered Env variants. b Western blot analysis of viruses pseudotyped with WT CH040 Envs or with CH040 Env variants. c–e Phenotypic characterization of CH040 Env variants. Cell–cell fusion (c), cell–cell transmission (d), and cold sensitivity (e) of viruses pseudotyped with WT HIV-1CH040 Envs or indicated engineered Env variants.

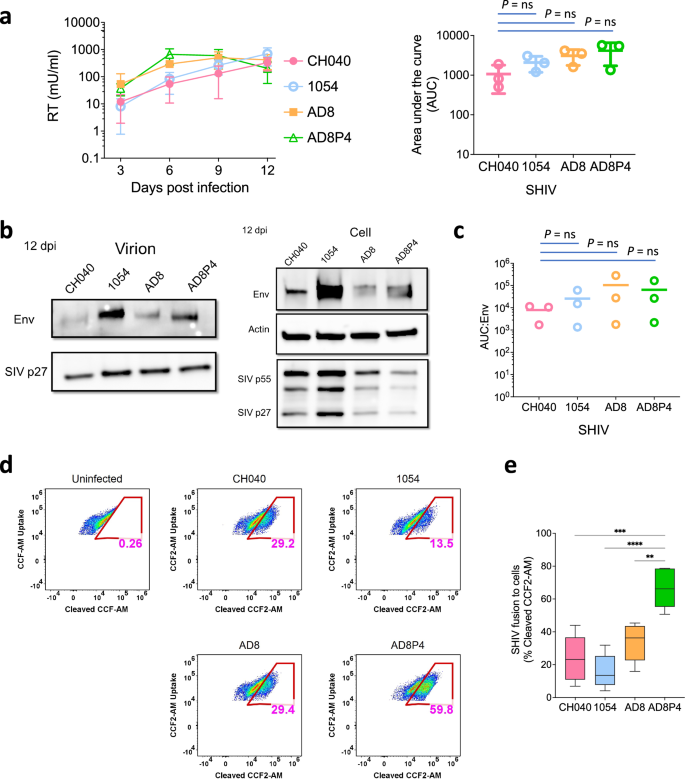

To study how CH040 Env function during multiple cycles of viral replication in target cells we used SHIVs encoding different Env variants and monitored their replication over time in PtM lymphocytes (Fig. 5). All four SHIVs: CH040, 1054, AD8, and AD8P4 (an AD8-derived clone isolated after 4 passages in rhesus macaques) have been previously tested in macaques and replicated to high levels49. Replication of the 4 SHIVs in PtM lymphocytes was robust and exhibited comparable levels after 9 days. However, AD8 and AD8P4 SHIVs exhibited faster kinetics of replication relative to 1054 and CH040 SHIVs, both carrying HIV-1 Envs isolated from T/Fs, during the first 6 days in culture. As a result, we identified an overall trend of higher replication of the AD8 and AD8P4 relative to the other SHIVs based on analysis of the area under the curve (AUC) during replication (Fig. 5a). Further evaluation of Env expression during the course of replication detected low levels of CH040 Envs on SHIV virions compared to the levels of 1054 Envs but CH040 Env expression was comparable to AD8 Env expression (Fig. 5b). We used the SHIV BlaM-Vpr assay to measure the ability of different SHIVs to mediate viral and target cell membrane fusion, which is an important step during viral entry (Fig. 5d–e). CH040 SHIV fusion activity was comparable to the fusion of AD8 SHIV and more efficient than the fusion activity of 1054 SHIV. Of note, the fusion activity of SHIV AD8P4, which was adapted in macaques, was substantially higher than all other SHIVs, suggesting that this activity was important for in vivo replication.

a Left, replication kinetics of indicated SHIVs in pig-tailed macaque (PtM) lymphocytes over a 12-day time course. Reverse transcriptase (RT) activity in viral supernatants is plotted against days post-infection. Right, area under the curve (AUC) for SHIV variants (indicated on the x-axis) calculated from the replication curves on the left. b Western blot analysis of virions (left) and whole cell extracts (right) harvested at twelve days post-infection from PtM lymphocytes infected with indicated SHIVs. Immunoblotting performed using anti-Env, anti-SIV p27, and anti-actin antibodies. c AUC for indicated SHIV variants normalized to per virion Env level (Env levels normalized to p27; Env:p27). Results (a, c) represent average ± sd of three independent experiments. d Representative flow cytometry plots indicating viral fusion (% of cells) detected by SHIV BlaM-Vpr assay. Fluorescence of uncleaved CCF2-AM uptake and cleaved CCF2-AM substrate was measured by Attune NxT flow cytometer using the VL1 and VL2 channels, respectively. Fusion activity of indicated SHIVs with PtM lymphocytes was measured as percentage of cells containing cleaved CCF-AM substrate. e Viral fusion (% of cells) for indicated SHIV variants (x-axis). Results represent average ± sd of five independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to assess statistically significant difference between the groups. ****p < 0.0001; ***p = 0.0002; **p = 0.0028.

Here we identified T/F Envs that are highly resistant to many different bnAbs without prior interactions with these bnAbs (pre-existing resistance). Several studies have documented a general drift in the viral population towards increased resistance to bnAbs47,48 and additional investigations point to specific examples27,46,59,60. Despite global resistance, CH040 Envs were still sensitive to 3 out of 4 (75%) of the CD4bs bnAbs tested, suggesting that maintenance of minimal CD4bs architecture was important for efficient viral entry. Even with high resistance phenotype, CH040 exhibited efficient entry, with high cell-cell transmission and cell-cell fusion activities. All entry activities were mediated by Envs with comparable expression levels as other Envs on cell/pseudovirus surfaces.

Engineering CH040 Env variants that contained amino acid changes in putative epitopes of bnAbs allowed us to evaluate the need of these amino acids for neutralization and the potential breadth of different bnAbs in the context of CH040 Env changes. Among the tested bnAbs, N6 and PGT151 exhibited the broadest neutralization activity. N6 CD4bs bnAb is one of the most promising bnAb currently tested in clinical trials and potently neutralizes 98% of HIV isolates in vitro27. We have recently evaluated the sensitivity of VRC01-resistant strains from the AMP trial to N6 and detected several T/F strains resistant to N650. Some of which were associated with incompletely closed Envs.

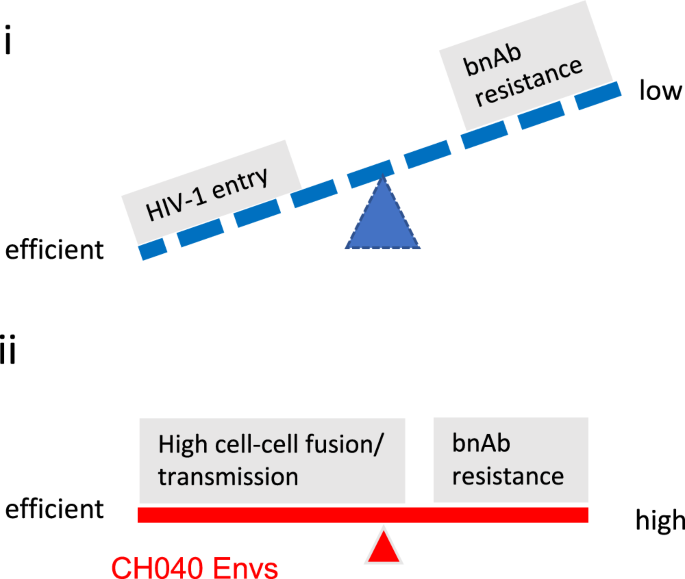

Our study has several limitations. We studied only one strain (CH040) and tested the effect of only a few changes. We also used the gold-standard pseudovirus preparations that utilize HIV-1 proteins of the NL-43 strain rather than molecular clones with the full-length native viral genomes. Nevertheless, our study highlights the potential ability of multi bnAb-resistant HIV-1 strains to replicate at high levels and these strains may be of public health concern. Our results suggest that CH040 Envs mediate viral replication at similar levels as Envs of other primary HIV-1 strains and can efficiently replicate in vitro. Previous studies documented efficient SHIV CH040 replication in vivo49. These insights add to our previous study50 that investigated in vivo evolution of CH040 in an infected individual and showed comparable (slightly higher) infectivity of CH040 evolving viruses based on consensus sequences of viruses from 10 time points, with a decrease in resistance of the evolving viruses to a subset of bnAbs. While our previous study50 evaluated Env conformational flexibility and how in vivo evolution altered Env conformation and sensitivity to bnAbs, in the current study we focused on assessing CH040 Envs and the relationship between bnAb resistance and efficient HIV-1 entry. Introducing a few additional changes that could potentially compromise the integrity of bnAb epitopes had no significant effects on entry compatibility of CH040 in most cases and some of these changes could increase bnAb sensitivity. In contrast to these changes in CH040 Envs, some changes in Env amino acid sequence could be detrimental61. By definition of broad, most HIV-1 strains are sensitive to bnAbs; however, our study suggests that at least in one HIV-1 strain (CH040) some of the pathways to move from sensitive to resistant phenotype do not necessarily decrease entry efficiency (Fig. 6). Together with high resistance to many bnAbs against different sites of Env vulnerability, CH040 Envs represent an enhanced challenge for the immune system and for HIV-1 vaccine development. Additional reported resistant HIV-1 strains include the clade C strains CAP8.6F, CAP255.16, and Du156.12 that show increased resistant profile to bnAbs targeting the CD4bs (VRC01), V2-glycan (PG9-like but not CAP256-VRC26-like epitopes) and MPER (4E10). In some cases, higher glycan density and longer V1, V2, and V4 loop lengths of gp120 were strongly associated with neutralization resistance; and there was no neutralization phenotype difference between pre-seroconversion and post-seroconversion HIV-1 strains62.

Many HIV-1 strains exhibit efficient entry and low bnAb-resistance (i); but some strains, such as CH040, can very efficiently enter target cells and still highly resist multiple bnAbs (ii).

Overall, our results suggest that efficient HIV-1 entry and resistance to multiple bnAbs may evolve independently. Thus, development of bnAb-resistance is not necessarily associated with viral fitness cost that affects entry. These insights highlight different aspects of HIV-1 strains of public health concern and provide additional considerations for the development of HIV-1 prevention and therapy strategies.

Methods

Cell lines

Cell line sources and maintenance have been previously described. 293T cell were purchased from the ATCC; TZM-bl and CEM CD4+ cells were obtained from the NIH HIV Reagent Program. Cf2-Th/CD4+CCR5+ cells were a kind gift from Joseph Sodroski (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute). SupT1.CCR5 (SupT1.R5) cells stably expressing the human CCR5 coreceptor were a kind gift from James Hoxie (University of Pennsylvania). All cell lines were tested negative for mycoplasma. 293T cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 100 units/mL of penicillin (all from Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific). Cf2-Th/CD4+CCR5+ cells were grown in the presence of 400 µg/ml G418 and 200 µg/ml hygromycin B selection antibiotics (both from Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific). CEM, SupT1.CCR5 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Immortalized pig-tailed macaque (PtM) CD4+ lymphocytes63 were cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1x Anti-anti (anti-microbial/anti-mycotic, Gibco), and 100 U/ml of interleukin-2 (Roche) (complete IMDM).

Site-directed mutagenesis

Plasmids expressing CH040 Env variants were generated according to Stratagene QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis (SDM) protocol using the CH040 Env-expressing plasmid (between 5–25 ng used as a template), PfuUltra II Fusion HotStart DNA polymerase (Agilent; catalog number: 600674), and the following primers:

CH040-D279E-F: 5′-gtaattagatcagtcaatttcagtgagaatgctaaaacaataatagtacaact-3′

CH040-D279E-R: 5′-agttgtactattattgttttagcattctcactgaaattgactgatctaattac-3′

CH040-S461N_N462D-F: 5′-caagagatggtggttacgagaacgacgagactgatgagatcttcag-3′

CH040-S461N_N462D-R: 5′-ctgaagatctcatcagtctcgtcgttctcgtaaccaccatctcttg-3′

CH040-S461G_N462T-F: 5′-caagagatggtggttacgagggcaccgagactgatgagatcttcag-3′

CH040-S461G_N462T-R: 5′-ctgaagatctcatcagtctcggtgccctcgtaaccaccatctcttg-3′

CH040-W672L-F: 5′-gataaatgggcaagtttgtggaatctgtttgacataacaaactggctgtg-3′

CH040-W672L-R: 5′-cacagccagtttgttatgtcaaacagattccacaaacttgcccatttatc-3′

CH040-W680G-F: 5′-gaattggtttgacataacaaactggctgggctatataaaaatattcataatgatagtagg-3′

CH040-W680G-R: 5′-cctactatcattatgaatatttttatatagcccagccagtttgttatgtcaaaccaattc-3′

CH040-276-DLN-TGN-282-F:

5′-gtttagcagaagaagaggtagtaattagatcagtcgatctcaatgacactggtaacacaataatagtacaactgaataaatctgtagaaat-3′

CH040-276-DLN-TGN-282-R:

5′-atttctacagatttattcagttgtactattattgtgttaccagtgtcattgagatcgactgatctaattactacctcttcttctgctaaac-3′

We incubated the SDM reaction products with DpnI (New England Biolabs) to enzymatically digest the template plasmid and transformed the products into XL10-Gold bacteria (Agilent; catalog number: 200315). DNA from positive colonies was sequenced to confirm the required mutation(s).

Production of single-round recombinant pseudoviruses

We produced recombinant luciferase-expressing pseudoviruses in 293T cells by transfection of 3 plasmids as we previously described15,64,65. After a 48-h incubation, pseudovirus-containing supernatant was collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 600–900 g at 4 °C. The amount of p24 in the supernatant was measured using the HIV-1 p24 antigen capture assay (Xpress Bio; catalog number: XB-1000) and the pseudoviruses were frozen in single-use aliquots at −80 °C.

Viral infection assay

Viral infection assay was performed as previously described66,67. Antibodies against HIV-1 Env were serially diluted in DMEM, and 30 μL of each tested concentration was dispensed into a single well (each concentration was tested in duplicate in each experiment) of a 96 well-white plate (Greiner Bio-One, NC). Pseudoviruses were thawed at 37 °C for 1.5 min and 30 μL were added to each well. After a brief incubation, 30 μL of 2.0 × 105 Cf2Th-CD4+/CCR5+ target cells/mL suspended in DMEM were added to each well. Pseudoviruses were typically pre-titered on the same target cells and volumes corresponding to ~1–3 million relative light units (2-s integration using Centro XS3 LB 960 luminometer) were used in all experiments. After 48-h incubation, the medium was aspirated, and the cells were lysed with 30 μL of Lysis Buffer; firefly luciferase activity was measured with 2-s integration time using a Centro XS3 LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, TN).

Flow cytometry

HEK 293T cells were co-transfected with the specified Env-expressing plasmids and a GFP-expressing plasmid (to evaluate transfection efficiency) using calcium phosphate. Cells were transfected in the presence of 25 μM chloroquine, and the medium was replaced after an overnight incubation. Seventy-two hours post-transfection the cells were washed with Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS; Millipore Sigma; catalog number D8537-500ML), detached with Accutase™ Cell Detachment Solution (BD Biosciences; catalog number 561527), and resuspended in 5%FBS/PBS blocking buffer [5% Fetal Bovine Serum (Gibco; catalog number A5209402) in PBS]. The cells were centrifuged at 100g for 5 min, resuspended in 5% FBS/PBS and 500,000 cells were incubated with 1 µg/ml N6 bnAb (NIH HIV Reagent Program) with shaking. After 30 min, the cells were washed, resuspended in 5%FBS/PBS and 1.3 µl of Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated donkey anti-human IgG (Jackson Immunolaboratories; catalog number 709-136-149; reconstituted according to manufacturer’s instructions) was added to each tube. The cells were incubated for 30 min with shaking, washed with 5% FBS/PBS, then washed with PBS and analyzed by BD Accuri C6 Plus flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10. Tubes were centrifuged at 4 °C and incubated at room temperature during all steps of the experiment.

Cell-cell fusion assay

Cell-cell fusion was measured as previously described with HIV-1 Tat as a transactivator and TZM-bl cells as reporter target cells66,68,69. In a 6-well plate, 5.0 × 105 293T cells were co-transfected with HIV-1 Env-expressing and HIV-1 Tat-expressing plasmids at a ratio of 1:6 using Effectene (Qiagen) and incubated for 48 h. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, 10,000 TZM-bl reporter cells/well were added to 96-well white plates (Greiner Bio-One, NC) and the plates were incubated overnight. After 24 h, the transfected 293T cells were detached using 5 mM EDTA/PBS, washed once, resuspended in fresh media and 10,000 cells were added to 96 plates containing the pre-incubated TZM-bl cells. Plates were incubated for 3, 6, and 9 h, and cells were then lysed; firefly luciferase activity was measured with 2-s integration time using a Centro XS3 LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, TN).

Cell-to-cell transmission assay

Cell-cell transmission was measured as previously described56. Briefly, 106 CEM CD4+ T cells were electroporated with 3 µg of the reporter plasmid pUCHR-EF1a-inNluc, 2 µg of the packaging plasmid pNL4-3ΔEnv, and 1 µg of the Env-expressing plasmid using Neon NxT Transfection System (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Electroporation was carried out using 100 µl tips and the Neon NxT was set to 1230 V and 40 ms × 1 pulse. Transfected cells were immediately mixed with 5 × 105 SupT1.CCR5 target cells in 1 ml of culture medium and washed twice to remove plasmid DNA from the medium before incubation. The cell mixture was divided into two replicas and incubated each one in 1 ml growth medium in a 12-well plate for 72 h. Cells from the plate were then transferred to 1.5 mL tubes, pelleted by centrifugation, and lysed in 50 µl of Promega Glo lysis buffer. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 2 min and transferred to a white 96-well plate. The level of infectivity was evaluated by the addition of 30 µl of NanoGlo Luciferase substrate (Promega) per well and measurement of nano luciferase activity using the Centro SX3 LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, TN).

Data analysis

Dose-response curves were generated by fitting the data to a four-parameter logistic equation using Prism 9 program (GraphPad, San Diego, CA), which calculated IC50 and SEM according to the fitted curves70,71,72. Dose-response curves of viral infectivity decay during cold exposure was fitted to one-phase exponential decay using Prism 9 Program.

SHIV production

Full-length proviral SHIV plasmids encoding CH040, 1054, AD8, and AD8P4 Env have been described previously49. Replication-competent SHIV stocks were generated as described previously73. The viral titer of SHIV stocks was determined by infecting TZM-bl cells (NIH AIDS Reagent program; catalog number 8129) and staining for β-galactosidase activity 48 h post-infection74.

Reverse transcriptase activity assay

RT activity assay was performed as described previously75. Briefly, 5 µl of viral supernatant, viral stock or RT standard was lysed in 5 µl of 2x lysis buffer (100 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 0.25% Triton X-100, 40% glycerol) in the presence of 4U RNaseOUT (Invitrogen) for 10 min at room temperature. Viral lysate was diluted 1:10 by adding 90 µl of nuclease-free water (Life Technologies). qRT-PCR reactions were prepared by mixing 9.6 µl of diluted viral lysate with 10.4 µl of reaction mix containing 10 µl of 2x Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher), 0.1 µl of 4U/µl RNaseOUT, 0.1 µl of 0.8 µg/µl MS2 RNA template (Roche), and 0.1 µl each of 100 µM forward 5′-TCCTGCTCAACTTCCTGTCGAG-3′ and reverse 5′-CACAGGTCAAACCTCCTAGGAATG-3′ primers. qRT-PCR was performed using a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). Viral titers were calculated from a standard curve generated using recombinant reverse transcriptase (MilliporeSigma; catalog no. 382129).

SHIV replication time course

Replication of SHIVs was assessed as described previously73. Briefly, 4 × 106 PtM lymphocytes were infected at a MOI of 0.02 by spinoculation at 1200 × g for 90 min at room temperature. After spinoculation, cells were washed four times with 1 ml of complete IMDM, re-suspended in 5 ml of complete IMDM and plated in one well of a 6-well plate. Every three days, two-third of the cultures were harvested and replenished with fresh, complete IMDM. Viral supernatants were collected from the harvested cultures by pelleting at 650 g for 5 min at room temperature. RT activity in viral supernatants was measured using the RT activity assay.

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell extracts were prepared by lysing the cells in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton-X, 150 mM NaCl, 1% deoxycholic acid, 2 mM PMSF). For virion incorporation, virus-containing supernatants from the infected cell cultures were centrifuged at 650g for 5 min at room temperature. Cell-free supernatant was filtered through 0.2 µm filter and then pelleted through a 25% sucrose cushion by ultracentrifugation for at 28,000 rpm for 90 min at 4 °C. Virus pellets were lysed in 70 μl of RIPA buffer for 10 min at room temperature. The concentration of SIV p27 in the viral lysates was determined by RT assay, and normalized amounts of lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted. Standard Western blotting procedures were used with the following antibodies: HIV-1 gp120 (NIH AIDS Reagent program; catalog number 288), SIV p27 (ABL; catalog number 4323), and β-Actin (Proteintech; catalog number 66009-1-Ig). Protein expression was quantified by measuring the band intensities of Env and p27 using ImageJ software. The ratio of Env to p27 band intensities was calculated to determine per virion Env level.

SHIV fusion assay

SHIV β-lactamase-Vpr (BlaM-Vpr) virus fusion assay was performed as described previously75. Briefly, SHIVs containing Blam-SIVmac239 Vpr fusion protein were generated by co-transfecting HEK293T cells with 4.5 μg of proviral SHIV plasmid and 1.5 µg of pcDNA3.1-Blam-SIVmac239 Vpr plasmid using Fugene 6 transfection reagent following manufacturer’s protocol. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, virus-containing supernatant was harvested, passed through a 0.2 μm sterile filter, concentrated ~10-fold using Amicon Ultracel 100 kDa filters (MilliporeSigma), aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. RT activity of viral stocks was measured using the RT activity assay. Hundred thousand (105) PtM lymphocytes in 100 µl of complete IMDM were infected with Blam-SIVmac239 Vpr-containing SHIVs equivalent to 500 mU of RT by spinoculation at 1200 g for 90 min followed by incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 h. Fusion-mediated SHIV entry was quantified by monitoring the conversion of fluorescent BlaM CCF2-AM substrate dye as described. After infection, cells were washed once with 300 µl of cold CO2-independent media (Gibco) without FBS and resuspended in 100 µl of CO2-independent media supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were incubated with CCF2-AM substrate (LiveBLAzer CCF2-AM Kit, Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol in the presence of 1.8 mM Probenecid (MilliporeSigma) for 2 h. Cells were washed three times with 300 µl of cold CO2-independent media without FBS, once with 1x PBS, fixed with 200 µl of 2% paraformaldehyde, washed once with 1x PBS, and resuspended in 400 µl of FACS buffer. The fluorescence of uncleaved and cleaved CCF2-AM substrate was measured on Attune NxT flow cytometer using the VL1 (for uncleaved CCF2-AM uptake) and VL2 (for cleaved CCF2-AM) channels. The data was acquired by gating 20,000 living cells and analyzed using FlowJo version 10.7.1.

Responses