Increasing polymyxin resistance in clinical carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in China between 2000 and 2023

Introduction

The widespread dissemination of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) poses an increasing threat to human health. To date, carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) has become the most common species of CRE. As one of the few remaining antibiotic classes that exhibit bactericidal activity against CRKP, polymyxins have been increasingly used as the last resort option for treatment of CRKP infections, despite the fact that these drugs exhibit nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity1. However, emergence of polymyxin-resistant bacteria has been recorded, presumably as a result of overuse of polymyxins. The China Antimicrobial Surveillance Network (CHINET, https://www.chinets.com/) revealed that the colistin resistance rate in 16,125 CRKP strains collected in China in 2023 was 11.8%. According to a systematic review covering isolates collected from 58 nations during the period 1987 through 2020, the overall prevalence of colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae worldwide was about 11.64%, among which a rate of 10.17%, 16.16%, and 18.67% was recorded in Asia, Europe and America, respectively2. Resistance to polymyxins has been reported worldwide, especially in CRKP strains collected from clinical settings3. Various studies have identified colistin-resistant and carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae as an independent risk factor which is closely associated with adverse outcomes and high mortality in hospitalized patients4,5; hence the increasing prevalence of such strains represents a growing public health threat.

Structural modification of lipopolysaccharide as a result of mutations in the two-component system-encoding genes (phoP/phoQ and pmrA/pmrB), the mgrB gene (a strong negative regulator of phoP/phoQ), and genes that encode efflux pumps and lipid A biosynthesis functions are the major mechanisms mediating expression of colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae3. The plasmid-mediated mobile colistin resistance gene (mcr) and its variants are also known to play an important role in the transmission of colistin resistance6, thereby further aggravating the situation. A recent study shows that high-level polymyxin resistance in CRKP isolates is predominantly attributed to lipid A modifications as a result of mutational changes in the chromosome, especially disruption of the mgrB gene caused by insertional elements7, among which members of the IS5 family members are the most commonly identified in polymyxin resistant CRKP strains8,9.

The increasing prevalence of clinical polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains warrants further study of their epidemiological features and molecular mechanisms that underlie resistance formation. In this study, we retrospectively identify 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates from 4455 non-repetitive clinical CRKP collected from 18 Chinese provinces during the period 2000–2023. The prevalence of polymyxin-resistant isolates among the clinical CRKP strains collected in different years is determined. Molecular and genetic analysis of these strains show that clonal dissemination of polymyxin-resistant CRKP is frequently observed in hospitals in China, and that chromosomal mutations are the predominant mechanisms of polymyxin resistance in these polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains. Importantly, our data also shows that a high proportion of polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains carry a hypervirulence-encoding plasmid and simultaneously exhibit multidrug resistance and hypervirulence.

Methods

Bacterial collection

A total of 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates were identified among 4455 non-duplicated CRKP strains collected from 18 provinces in China during the period 2000–2023 (Supplementary Data 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Species identification was determined by performing MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker, Germany). The prevalence rate of polymyxin-resistant CRKP was determined; the 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated by using the Poisson distribution formula.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The susceptibility of polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates to 15 commonly used antibiotics (including amikacin, aztreonam, cefepime, cefmetazole, cefoperazone-sulbactam, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftazidime-avibactam, ciprofloxacin, ertapenem, meropenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, polymyxin B and tigecycline (Sigma-Aldrich, USA)) was determined using broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines10. Susceptibility of the test strains to tigecycline and polymyxin B was interpreted according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility testing (EUCAST) (http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/) breakpoints and results for other antibiotics were interpreted according to the CLSI guidelines. E. coli ATCC 25922 was utilized as a quality control.

Whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Genomic DNA of polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates was extracted by using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, USA) and then sequenced by the Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina, CA) by adopting a 2*150 bp paired-end sequencing strategy. Raw reads were trimmed with Trimmomatic v0.38 to remove low quality sequences11. Sequence assembly was conducted by SPAdes Genome Assembler v3.11.112, after which the assembled sequences were annotated with RAST13. In addition, Kleborate v2.0.4 was applied to identify the sequence types (STs), KL types, virulence genes and resistance genes14,15. The core-SNP alignment of test strains was generated by Snippy v4.6, with assembled genome sequence of strain 14-109 as a reference16. The alignment was then utilized to infer a phylogenetic tree using RAxML v8.2.1217. The phylogenetic tree was then visualized and annotated by iTOL v418. Pairwise single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) distances were determined by snp-dists v0.8. To screen for virulence plasmids, genome sequences of the test strains were compared to a reference plasmid pLVPK19 using the BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG) v0.95.2220.

Identification of mutations in polymyxin resistance-associated genes in K. pneumoniae

Mutations in polymyxin resistance-associated genes such as the two-component system-encoding genes phoPQ, pmrAB and crrAB and the corresponding negative regulator gene mgrB were identified by alignment against the genome of K. pneumoniae strains NTUH-K2044 (accession: NC_012731.1) and MGH78578 (accession: NC_009648.1). Insertion sequences in the mgrB gene were identified by ISfinder21. Mobile colistin-resistance genes (mcr-1 to mcr-10) were identified by genome comparison22,23,24.

Mucoviscosity and quantification of capsule production

Mucoviscosity was determined by the sedimentation method25. Briefly, overnight culture in Luria Bertani (LB) broth was incubated to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 in fresh LB broth and grown at 37 °C. Upon 6 h’ incubation, bacterial culture was normalized to an OD600 of 1.0 and centrifuged for 5 min at 1000*g. Supernatant was carefully collected without disturbing the pellet for OD600 determination.

Uronic acid production was determined as previously described25. In brief, 500 µL bacterial culture (normalized to an OD600 of 1.0) used in the mucoviscosity assay was added to 100 µL 1% Zwittergent 3–14 in 100 mM citric acid, followed by incubation for 20 min at 50 °C. The mixture was centrifuged at 13,000*g for 5 min and 300 µL supernatant was added to 1.2 mL absolute ethanol, followed by incubation at 4 °C for 20 min and centrifugation for 5 min. The precipitate was dried and resuspended with 200 µL distilled water, followed by mixing with 1.2 mL 12.5 mM sodium tetraborate in sulfuric acid and incubation for 5 min at 100 °C, immediately incubating on ice for 10 min. Next, 20 µL 0.15% 3-phenylphenol in 0.5% NaOH was added to the mixture. Following incubation at room temperature for 5 min, the absorbance at 520 nm was measured. The content of uronic acid was determined according to a standard calibration curve depicting the relationship between content of glucuronic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and optical density. Results were presented as mean and standard deviation of four independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t test.

Mouse sepsis model

Male NIH mice (~20 g, 4 week) were purchased from Guangdong Center for Experimental Animals (Guangzhou, China) and allowed for food and water throughout the study. To reduce biological variability, only male mice were used in the infection model. NIH mice randomly assigned into each group (n = 5) were infected intravenously with 5.0*106 CFU of K. pneumoniae strain. Survival of mice was recorded for 144 h post infection. ST11 CR-hvKP strain HvKP4 and ST11 CRKP strain FJ8 were included as hypervirulence and low virulence control strains26. All experimental protocols followed the standard operating procedures of the Biosafety Level 2 animal facility and animal experiments were approved by Animal Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Statistics and reproducibility

Results in mucoviscosity assay and uronic acid production were presented as mean and standard deviation of four independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired Student’s t test by GraphPad Prism 8.0. Animal experiments were conducted twice to confirm the consistency of the data. The 95% confidence interval was calculated by using the Poisson distribution formula.

Ethics statement

Ethical permission of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2023-0611). Animal infection tests were approved by Animal Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Prevalence of polymyxin-resistant CRKP in China during the period 2000–2023

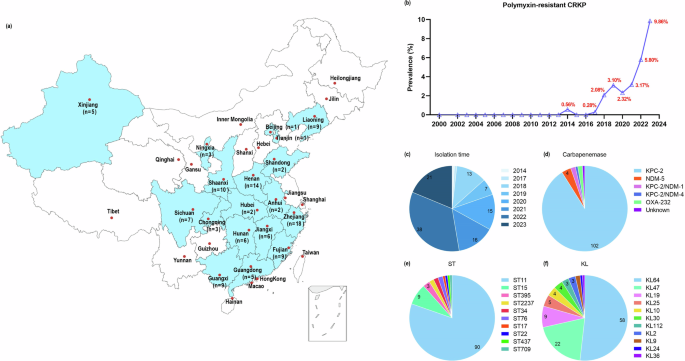

A total of 4455 non-duplicated clinical CRKP strains were collected from hospitals located in various provinces in China during the period 2000–2023, among which 112 isolates were found to be polymyxin B resistant, accounting for 2.51% (112/4455) of the test strains. Polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates were not detected before 2014; thereafter, the prevalence of polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates varied between different years during the period 2014–2023 but apparently exhibited an increasing trend (Table 1, Fig. 1b). The detection rates of polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates fluctuated between 0.56% (1/179, 95% CI 0.10–3.10%) and 0.28% (1/354, 95% CI 0.05–1.58%) during 2014 and 2017, then dramatically increased to 2.08% (13/625, 95% CI 1.22–3.53%) in 2018 and remained at a relatively high level (3.17%, 16/505, 95% CI 1.96–5.09%) until 2021, followed by further increase to a rate of 5.80% (38/655, 95% CI 4.25–7.86%) in 2022 and 9.86% (21/213, 95% CI 6.54–14.60%) in 2023 (Table 1, Fig. 1b, c). Among the 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates, Zhejiang province contributed the largest number of isolates (n = 18) among the provinces participated in the surveillance, followed by Henan (n = 14), Shaanxi (n = 10), Fujian (n = 9), Guangxi (n = 9) and Liaoning (n = 9) (Fig. 1a).

a The map depicted the relative prevalence of 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates among different provinces in China. The map was created based on a map from d-maps.com (https://d-maps.com/index.php?lang=en), which was free for use. b Changes in prevalence rate of polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates during the period 2000 to 2023. The four pie charts showed the isolation time (c), different types of carbapenemases expressed by the test strains (d), and prevalence the ST type (e) and KL type (f) of the 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates tested in this study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and antimicrobial resistance genes in polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains

Antimicrobial susceptibility test results showed that all the polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates exhibited multidrug resistance phenotypes. In addition to resistance to polymyxin B and meropenem, all the test strains were found to be resistant to ertapenem, cefepime, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, piperacillin-tazobactam and cefoperazone-sulbactam. In addition, they also exhibited a high rate of resistance to aztreonam, ciprofloxacin and amikacin, with 99.11% (111/112), 96.43% (108/112) and 71.43% (80/112) of the strains exhibiting resistance to these three drugs respectively. However, most of the isolates remained susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam (92.86%, 104/112) and tigecycline (90.18%, 101/112) (Table 2).

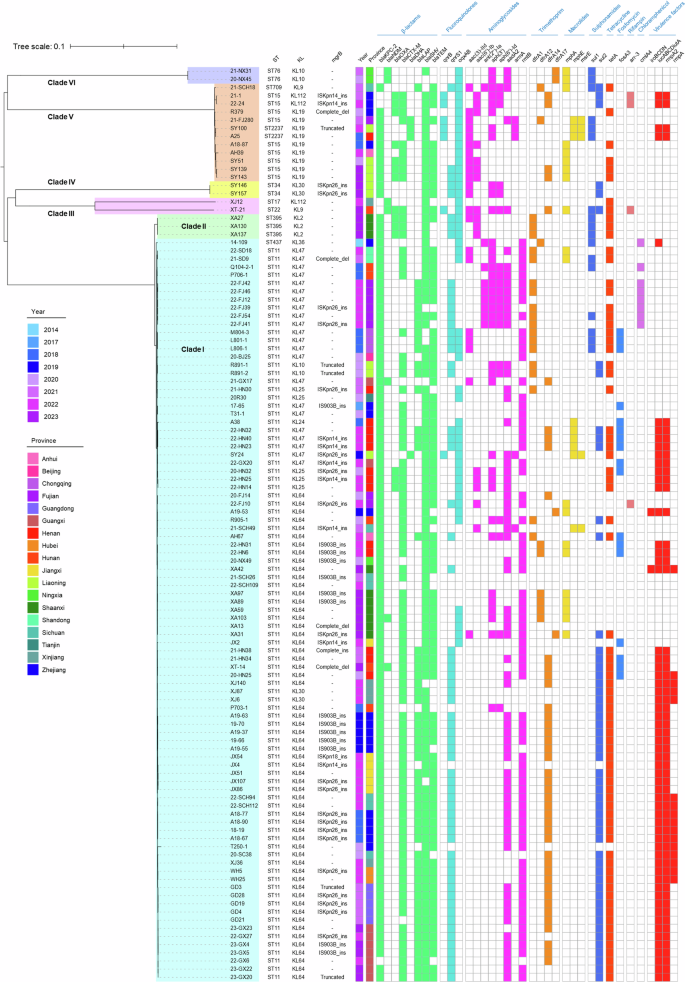

Among the 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates, carbapenem resistance was predominantly mediated by the blaKPC-2 gene (102/112). The remaining 10 strains included nine isolates that produced other carbapenemases including NDM-5 (n = 4), KPC-2 and NDM-1 (n = 2), KPC-2 and NDM-4 (n = 1), and OXA-232 (n = 2), and one isolate that did not produce any known carbapenemases (Fig. 1d). In addition to carbapenemase genes, polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates also carried multiple (3–20) antimicrobial resistance genes, including genes that encode extended spectrum β-lactamases (blaTEM, n = 89; blaCTX-M, n = 88; blaSHV, n = 104; blaLAP, n = 55; and blaOXA, n = 14), fluoroquinolone resistance genes (qnrS1, n = 63; qnrB, n = 7; and oqxAB, n = 48), aminoglycoside resistance genes (rmtB, n = 72; aadA2, n = 66; aph(3’), n = 37; aac(3)-IId, n = 21; aph(6’)-Id, n = 20; and aac(6’)-Ib, n = 16), trimethoprim resistance genes (dfrA14, n = 43; dfrA1, n = 18; and dfrA12, n = 9), macrolide resistance genes (mphA, n = 20; mphE, n = 9; and msrE, n = 5), sulfonamide resistance genes (sul1, n = 17; and sul2, n = 53), tetracycline resistance gene (tet(A), n = 74) and fosfomycin resistance gene (fosA3, n = 17) (Fig. 2). However, the mobile colistin resistance gene mcr was not detectable in these polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains. On the other hand, the mobile tigecycline resistance genes such as tet(X) and tmexCD-toprJ could not be detected in the 11 tigecycline-resistant isolates.

Phylogenetic tree of 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates collected from 18 provinces in China during the period 2014 to 2023. Three columns on the left depicted the ST, KL type and the mgrB gene mutations detectable in these isolates, respectively. The first two columns of the heatmap depict the collection time and origin of these isolates, followed by the antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors they harbored were depicted. Colored cells in each column represent the presence of a particular resistance gene or virulence factor as labeled at the top.

Molecular mechanisms that underlie expression of polymyxin resistance in CRKP strains

We next screened for genetic mutations in two-component system genes (pmrAB, phoPQ and crrAB) and the mgrB gene that are known to play a role in development of polymyxin resistance in K. pneumoniae. Mutations in the mgrB gene were the most frequently identified (52.68%, 59/112) in these polymyxin-resistant isolates, followed by pmrAB (6.25%, 7/112) and phoPQ (5.36%, 6/112) (Table 3). Moreover, the mgrB gene, which is regarded as the most important polymyxin resistance-associated gene, was frequently disrupted by specific insertion sequences (74.58%, 44/59), namely ISKpn26 (45.45%, 20/44), IS903B (31.82%, 14/44), ISKpn14 (20.45%, 9/44) and ISKpn18 (2.27%, 1/44). Other mutations in the mgrB gene included those which caused disruption of the open reading frame (n = 7), complete deletion (n = 5), as well as stop codon (K3*, n = 2) and missense mutations (C39G, n = 1).

Missense mutations in genes that encode two-component systems were also observed, including those which caused the G53C (n = 1) and G53V (n = 1) amino acid substitutions in the pmrA gene, the T157P (n = 3) and S85R (n = 2) changes in the pmrB gene, the E82K (n = 1) and Y98C (n = 1) substitutions in phoP, and the L62P (n = 2) and L247P (n = 2) substitutions in phoQ. Mutations that result in the A246T change in the pmrB gene and those which cause the E57G substitution in the pmrA gene were identified in 11 and one isolates, respectively; however, these mutations were reported to be not related to polymyxin resistance27,28. On the other hand, this study identified several mutations in the polymyxin resistance-related genes that have not been reported previously, including those associated with the L19P change in mgrB, the A37T change in pmrA, the T240M and P95Q substitutions in pmrB, the D191G substitution in phoP, and the I109T change in the phoQ gene. The underlying mechanism by which these mutations contributed to development of polymyxin resistance remained unclear and required further investigation.

Diversity of STs and phylogenetic relationship of the polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains

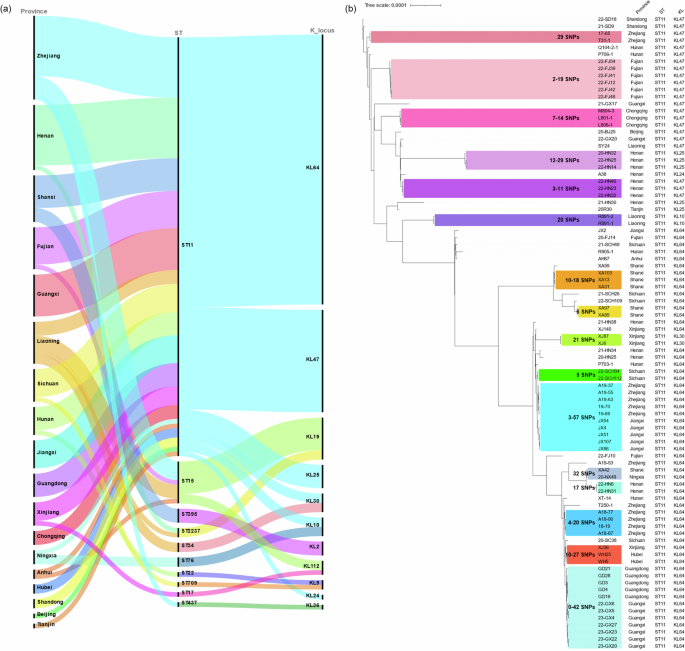

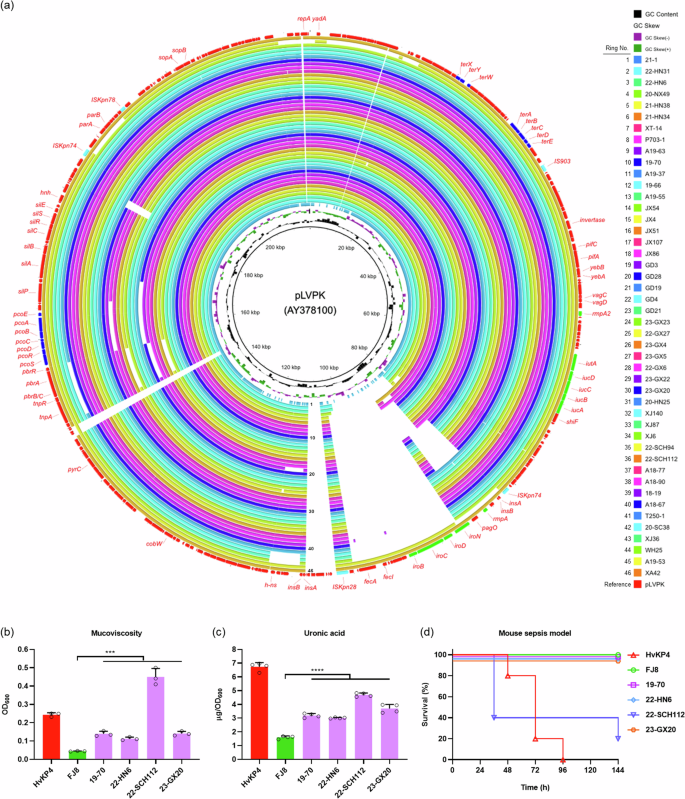

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) results revealed that the 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains belonged to 10 different STs. The most prevalent ST was ST11 (80.36%, 90/112), followed by ST15 (8.04%, 9/112) and ST395 (2.68%, 3/112) (Figs. 1e and 3a). These polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates belonged to 11 different KL types based on the structure of the capsular locus, among which the most prevalent KL type was KL64 (51.79%, 58/112), followed by KL47 (19.64%, 22/112), KL19 (8.04%, 9/112) and KL25 (4.46%, 5/112) (Figs. 1f and 3a). ST11 is considered as the most prevalent ST type among the CRKP strains in China29,30, which can be further assigned into several capsule types, with K64 and K47 being the two main types26,31. A total of 6 different KL types, including KL64 (58/90), KL47 (22/90), KL25 (5/90), KL30 (2/90), KL10 (2/90) and KL24 (1/90), were identified among the 90 ST11 polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains (Figs. 2 and 3a). A recent investigation further demonstrated that the ST11 clone in China was associated with KL64 and KL47, and suggested that dissemination of ST11 sub-lineages drove the transmission of carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (CR-hvKP) in China32. Among the 58 ST11-KL64 isolates documented in this study, 16 were found to carry genes that encode the virulence factor aerobactin (iucABCDiutA) and the regulators of the mucoid phenotypes (rmpA and rmpA2). Another 30 isolates were found to carry the virulence genes iucABCDiutA and rmpA2, two isolates were found to carry the iroBCDN genes which encode the virulence determinant salmochelin. Among the 22 ST11 KL47 polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains, however, only six were found to carry the virulence genes iucABCDiutA and rmpA2. Genome sequences of the polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains were also subjected to screening of virulence plasmids, using plasmid pLVPK as a reference, with results showing that these strains harbored a total of 46 pLVPK-like virulence plasmids (Fig. 4a), among which 43 pLVPK-like virulence plasmids were recovered from ST11 KL64 type strains. These plasmids were found to exhibit close genetic relationship to each other; apart from the plasmids recovered from strains XA42 and A19-53, most of the plasmids were found to lack a ~17 kb genetic structure harboring the iroBCDN genes when compared to the reference plasmid pLVPK. The mucoviscosity, production of uronic acid and virulence potential in mouse sepsis model were determined as previously reported33 in four randomly selected pLVPK-like virulence plasmid carrying polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates, with HvKP4 and FJ8 being used as hypervirulence and low virulence controls26. Results showed that all four polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates carrying pLVPK-like virulence plasmid exhibited significantly increased mucoviscosity (Fig. 4b) and uronic acid production (Fig. 4c) when compared to that of FJ8, while virulence potential of these strains depicted in a mouse sepsis model varied (Fig. 4d), in which 22-SCH112 exhibited hypervirulence and other three exhibited low virulence. Consistent with previous report that polymyxin resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates could render them less virulent34, our data also showed that some of these polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates carrying pLVPK-like virulence plasmid remained hypervirulent, which could have an important clinical impact.

a Sankey plot showing the degree of association between the provinces from which the polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains were recovered, and the STs and KL types of such strains. Width of the line was proportional to the number of isolates. b Phylogenetic analysis of 90 ST11 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates. Strains covered by the same color on the phylogenetic tree represent the clonal transmission cluster with close SNPs distance. The three columns on the right depicted the origin, ST and KL type of ST11 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates, respectively.

a Alignment of virulence plasmids recovered from 46 polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates with the reference plasmid pLVPK (AY378100) using BRIG. pLVPK is in the outermost circle; virulence genes are highlighted in green, mobile elements are highlighted in light blue; genes that encode resistance to tellurate and copper are highlighted in dark blue. The structures of the 46 pLVPK-like virulence plasmids are depicted as circular maps; the names of the strains from which plasmids shown in the innermost to outermost circles were recovered are listed in the order of top to bottom on the right. b Mucoviscosity (***, P19-70 = 0.0003, P22-HN6 = 0.0002, P22-SCH112 = 0.0001, P23-GX20 = 0.0002, n = 3 biologically independent experiments), c Uronic acid production (****, P19-70 < 0.0001, P22-HN6 < 0.0001, P22-SCH112 < 0.0001, P23-GX20 < 0.0001, n = 4 biologically independent experiments.) Results were presented as mean and standard deviation of four independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t test by GraphPad Prism 8.0. d Virulence potential of polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates carrying pLVPK-like virulence plasmid. Mice (n = 5 biologically independent animals) were intravenously infected with 5.0*106 CFU of each K. pneumoniae isolate. Source data was provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Phylogenetic analysis based on the core genome SNPs of the 112 polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains showed that they could be clustered into six main clades, with Clade I being the predominant cluster (Fig. 2). Clade I was found to comprise 91 (81.25%, 91/112) polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains, including 90 ST11 and 1 ST437 isolates. Clade II consisted of three isolates that belonged to the ST395 type. Clade III consisted of two isolates of the ST17 and ST22 type. Clades IV and VI contained two isolates each of ST34 and ST76, respectively. Clade V consisted of 12 (10.71%, 12/112) isolates that belonged to ST15 (n = 10) and ST2237 (n = 2), respectively. Phylogenetic analysis was further performed to depict the genetic relatedness of the 90 ST11 isolates in clade I. Here, clonal transmission was defined as a pairwise SNPs distance of ≤45 between isolates of K. pneumoniae as proposed recently35. The results of phylogenetic analysis showed that clonal transmission of polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains frequently occurred in the same hospital (Fig. 3b). For example, clonal spread of such isolates was observed in hospitals located in 12 provinces, namely Zhejiang, Fujian, Chongqing, Henan, Liaoning, Shanxi, Xinjiang, Sichuan, Jiangxi, Hubei, Guangdong and Guangxi, involving a variety of SNPs. Further evidence of clonal dissemination of strains among hospitals located in different provinces include the discovery that strains XA42 from Shaanxi and 20-NX49 from Ningxia only varied by 32 SNPs; likewise, strains XJ36 from Xinjiang and WH25, WH5 from Hubei varied by 10-27 SNPs; five isolates from Zhejiang and five isolates from Jiangxi varied by 3–57 SNPs; and five isolates from Guangdong and seven isolates from Guangxi varied by 0-42 SNPs (Fig. 3b). These data suggest that polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains can be disseminated to neighboring provinces.

Discussion

Polymyxins have become the last-resort antibiotics used in treatment of CRKP infections. However, K. pneumoniae strains resistant to both carbapenem and polymyxin have been increasingly reported, and the molecular mechanisms that mediate expression of phenotypic multidrug resistance have been subjected to surveillance36,37. The polymyxin resistance rate in CRKP isolates accounted for 2.51% of all test strains in this study. This rate is regarded as being significantly higher than that of a multicenter investigation, which reported a colistin resistance rate of 1.98% among clinical CRKP strains collected from 28 hospitals in China in 2018 and 201938. This is because our study included strains collected during the period 2003 through 2013, a period in which all CRKP strains did not exhibit polymyxin resistance. It should be noted that the prevalence of polymyxin resistance in clinical CRKP reached 9.86% in 2023 in our study, which was quite close to that reported in the CHINET surveillance in 2023 (11.8%).

Inactivation of gene mgrB was considered the main mechanism that underlies the onset of polymyxin resistance in K. pneumoniae3,39. Genetic determinants associated with colistin resistance were identified for 216 colistin-resistant CRKP strains in a previous study, among which 81.9% were found to harbor chromosomal mutations in the mgrB gene, including disruptions by insertion sequences, deletions, premature stop codons and mutational frameshifts6. The predominant mechanism that mediates development of polymyxin resistance in this study was via genetic modulation of the mgrB gene, which was found to occur in 52.68% (59/112) of the test isolates, with insertion by IS elements such as ISKpn26 (33.90%, 20/59), IS903B (23.73%, 14/59) and ISKpn14 (15.25%, 9/59) being the key mutational event. ISKpn26, a member of the IS5 family, was the most common insertion element detectable in the mgrB gene in polymyxin resistant CRKP strains in this study. This finding is consistent with those reported in Italy9 and Switzerland40, in which IS5-like elements were mainly involved in insertion of the mgrB gene in polymyxin resistant CRKP strains. Our data are also consistent with the finding that the ISKpn26 element was commonly detected in the mgrB gene in such strains in Taiwan41 and Greece42. Genetic disruption of mgrB by the ISKpn18 element was first reported in Zhejiang province in China in 201843 but rarely reported elsewhere. In this study, polymyxin resistance mediated by ISKpn18 insertion in the mgrB gene was identified in an ST11 KL64 CRKP isolate (JX54) collected from Jiangxi province, which was a neighboring province of Zhejiang province, indicating that such strains are highly transmissible. Genetic alternations in the mgrB lead to upregulation of expression of the PhoPQ and PmrAB two-component systems, consequently conferring polymyxin resistance44. These mgrB-mediated polymyxin resistance mechanisms may enhance the ability of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae strains to cause infections in human; such strains therefore represent a growing threat to human health. Mutations in the mgrB gene that result in formation of a stop codon at K3*45 and the C39G46 substitution were reported in K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae isolates, respectively, both of which were collected from human clinical specimen. Mutations associated with the G53C39 and G53V47 changes in pmrA, the T157P48 and S85R39 substitutions in pmrB, and the L247P38 change in phoQ were found to cause 16 to 64-fold increase in the minimal inhibitory concentrations of colistin in clinical CRKP strains. Since the plasmid-mediated mobile colistin resistance gene mcr-1 was first reported in 201649, ten different mcr derivatives have been identified6. To date, Escherichia coli remains the dominant bacterial host of mcr genes, and identification of mcr genes in K. pneumoniae was uncommon50,51,52. In this study, plasmid-borne mcr genes were not detectable in these polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains, suggesting that polymyxin resistance in these strains is mainly attributed to chromosomal mutations.

As the most prevalent multidrug-resistant lineage in Asia53, ST11 CRKP was first observed to become a hypervirulent strain in China26, after which an increasing number of CRKP isolates which harbored multiple virulence factors and exhibited the ability to cause fatal nosocomial outbreaks have been reported worldwide26,54,55,56,57,58,59. In this study, over half (55/90) of the polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates that belonged to the ST11 lineage carried multiple virulence genes; 45 such strains were found to harbor a pLVPK-like virulence plasmid which is functionally related to that carried by notorious hypervirulent CRKP (CR-hvKP). CR-hvKP has recently been reported in many countries around the world, such strains are known to cause infections of higher mortality rate than CRKP strains60. Worryingly, polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates that express a hypervirulence phenotype are expected to cause life-threatening infections with exceptionally high mortality rate. The possibility that polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains are particularly efficient in acquiring the virulence genes and the hypervirulence-encoding plasmid needs to be investigated.

In conclusion, this study showed that the polymyxin resistance rate in CRKP strains collected from 18 Chinese provinces increased sharply from the year 2014 onwards. Inactivation of the MgrB protein was the main mechanism that mediate expression of the polymyxin resistance phenotype in these CRKP strains, whereas prevalence of plasmid-borne mcr genes in polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains was extremely low. Our study also highlighted the role of the IS elements, particularly ISKpn26, ISKpn14 and IS903B, in causing genetic alternations of the mgrB gene in polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that clonal spread of polymyxin-resistant CRKP isolates was a common event in the same hospital or even between hospitals located in different provinces. Worryingly, these polymyxin-resistant CRKP strains were often resistant to most commonly used drugs, leaving them only susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam and tigecycline. The emergence of polymyxin-resistant CRKP foreshadows an unprecedented crisis as these strains are resistant to almost all the last-resort antimicrobial agents. Continuous surveillance of polymyxin-resistant CRKP is necessary to prevent the further dissemination of these deadly pathogens in clinical settings in China.

Responses