Indoor positioning systems provide insight into emergency department systems enabling proposal of designs to improve workflow

Introduction

Emergency department (ED) crowding has become a major public health issue in many countries worldwide1. Crowding can be defined as a market failure when the demand for emergency care outstrips the availability of physical and human resources. Its consequences for patient outcomes, including delayed treatment, longer triage time, extended length of stay, and increased mortality, have been well documented2,3. ED crowding is closely related to market failures at other levels of the healthcare system, such as difficulties accessing primary care. Interventions designed to reduce the demand for emergency care by increasing access to primary care have been found to be effective at reducing unnecessary ED visits4,5. Another way to alleviate ED crowding is to address production capacities directly to meet the demand for emergency care. However, while one might think that simply expanding emergency units would solve this problem, a study showed that increasing ED bed capacity did not reduce the percentage of patients left without being seen and even had unintended consequences on boarding hours6. Therefore, one needs to identify how physical and human resources are used in the production of emergency care to determine which resources need to be increased or to find an alternative organization of production to optimize the use of existing resources.

In recent years, indoor positioning systems (IPSs) based on radio frequency signals have been widely developed for tracking objects and/or people due to their high precision7. IPS operates in a similar way to GPS and uses the principle of triangularization to determine the location of an object or person. The signals from GPS satellites are easily degraded by buildings, making this technology inappropriate for indoor environments. Instead, IPS based on radio frequency signals uses anchors placed directly inside the building. Radio frequency signals can be divided into continuous waves (e.g., Wi-Fi, radio frequency identification (RFID)) and pulse ultrawide band (UWB). Continuous wave IPS has been found to provide accuracy up to one meter, while UWB IPS can achieve centimeter-level accuracy owing to its high temporal resolution8. In this study, we experimented with an IPS based on UWB to track the activity of healthcare professionals during their shifts in an ED. We aim to explore how quasi-real-time data collected by the IPS could provide a better understanding of the organization and production of emergency care. Specifically, we investigate which information can be derived from IPS data to assess how healthcare professionals allocate their time and transit within the ED.

In the literature, many applications of IPSs for asset tracking in hospitals have shown potential for inventory and commodity management9,10. Beyond the aim of easily locating medical equipment in real time, a few studies have tested the use of passive RFID for object-based activity recognition, especially in the context of trauma resuscitation, where a list of objects can be defined as related to a given activity11,12. From the patient perspective, IPSs are also widely used for detecting falls in the elderly, in order to provide them timely treatment, as well as being used as a navigation tool for patients in healthcare facilities13,14. However, the use of IPS to directly track the motion of healthcare professionals in hospitals is still in an experimental phase. One study developed a Wi-Fi-based tracking system for task-phase recognition and task-progress estimation of assistant nurses15. The requirement is that the nature of the activities, their start and end points, and the different phases are known in advance through a task management system. The tracking system is subsequently used as a monitoring tool to detect in which phase of activity an assistant nurse is, as well as the estimated time remaining to complete the task. Another study used an RFID tracking system to measure clinician–patient contact and investigated its correlation with ED crowding16. Focusing on attending physicians, they found a positive correlation between the number of encounters per visit and ED crowding, suggesting a fragmentation of care activities when crowding increased. IPSs have also been studied as contact tracing tools among physicians, as a way to automatically detect and notify individuals who have had close contact with an infected person17,18.

The uniqueness of our study lies, in part, in the combination of IPS data with patient discharge data. Through IPS data, we delve into healthcare professionals’ time allocation and movement patterns over a long period of observation. This enables us to investigate the impact of ED crowding on the production of care by observing time allocations and walking distances at various occupancy levels. The method employed in this study provides new insights and offers an alternative to shadowing techniques to assess how the production of emergency care is organized. These results were obtained through experimentation with a UWB tracking system for healthcare professionals at the scale of an entire ED. While a few studies have experimented with IPSs based on continuous-wave radio frequency signals, to our knowledge, this is the first study of a UWB IPS designed to track the activity of ED healthcare professionals.

Our results indicate that the proportion of time spent on care-related activities ranges from 26% to 39% for doctors. In contrast, this share reaches approximately half of the time for triage nurses and intensive care unit nurses. The burden of non-care-related activities largely arises from time spent on administrative duties and transit. For doctors, the share of non-care-related activities is positively correlated with the occupancy level. The hourly distance walked by nurses (except triage nurses) increases with occupancy, while for doctors, the walking distance remains unchanged regardless of patient load. Moreover, IPS data allow walking distance to be related to the surface of activity. For example, doctors, who have the second-lowest accumulated walking distance, exhibit the highest ratio of distance walked relative to their surface of activity compared to other healthcare professional categories.

Methods

Data

An IPS based on UWB using multiple anchors and 27 tags (i.e., sensors) was tested at the emergency department of Le Corbusier Hospital in Firminy, France. The experiment took place from March 7th to April 21st 2022. During the study period, each medical staff member who provided informed consent to participate in the study wore a tag during their shifts to collect timestamped data on their location within the ED. The data were collected in quasi-real time, as records were collected 5 times per second. Each record included the location within the ED (i.e., coordinates) and a timestamp. More information on the specification of the IPS can be found in Supplementary Method 1, using the key criteria for evaluating an IPS proposed by Wichmann et al.19. Although tag users were anonymized, a label describing the type of medical staff, classified into eight subcategories, was associated with each tag. Among the 27 tags, six were associated with assistant nurses, two with triage nurses, two with intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, three with waiting room nurses, three with short-stay unit (SSU) nurses, two with managers, and nine with doctors and on duty doctors (see Supplementary Method 2 for a description of the labels). The study received approval in France from ethical committee of Le Corbusier Hospital, Firminy. Consent for participation in the study was done via personal invitation to health care professionals.

While IPS based on radio frequency signals benefits from high accuracy, noise is often observed in locations due to the complexity of the indoor environment8,20. Exploiting the large amount of data recorded in quasi-real time, we employed a smoothing algorithm consisting of aggregating the data into 10-second time windows to reduce noise (see Supplementary Method 2 for a description of the cleaning procedure).

To gather information on patient loads, we extracted the summary attendance to emergencies of every patient admitted to the ED during the study period. Patient flows and patient loads were computed based on the arrival and exit date and time.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects developed in the Declaration of Helsinki by the World Medical Association (WMA). The study received approval in France from ethical committee of Le Corbusier Hospital, Firminy. Consent for participation in the study was done via personal invitation to health care professionals in the emergency department of Le Corbusier hospital, Firminy, France.

Tag user label recognition algorithm – Supervised machine learning

Based on IPS data, we developed an algorithm capable of predicting the type (i.e., label) of healthcare professionals wearing the tag based on their movement and time spent in different areas of the ED. This algorithm could be particularly useful for multi-type workers, such as nurses who may switch multiple times among triage, ICU, waiting room, and SSU activities. Switches are not always scheduled and can be the result of exceptional circumstances such as sick leave or unexpected ICU admissions. First, the data were grouped into sequences of observations. A sequence was defined as all successive observations from the same tag, with a gap to the next record of less than 30 min. Then, we created a hexagonal grid over the entire ED floor plan to discretize the ED into a multitude of subareas (i.e., regular hexagons). Various hexagon sizes were tested, ranging from a diameter of 1 m to 3.5 m. For each sequence, we computed the proportion of time spent in each hexagon, which was used as a predictive feature. Finally, we employed a random forest classifier algorithm to predict our multiclass target variable (i.e., the type of healthcare professional) based on the predictive features. The model was implemented using the Python library scikit-learn. To reduce the risk of overfitting, we randomly split our sample into training and testing samples. Note that the split was performed while stratifying by the classes of the target variable to ensure that each class was preserved in both the training and testing samples. We tested various specifications of the model by varying the hyperparameters, the number of features selected based on their importance score (i.e., Gini coefficient), and the size of the hexagons when creating the grid.

Analysis of medical staff time allocation

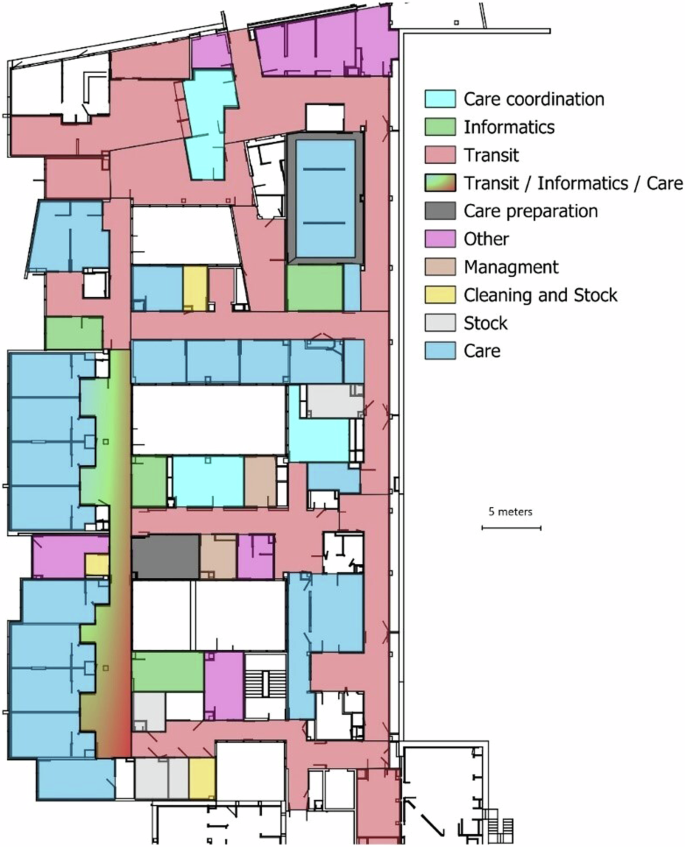

Exploiting timestamped locations, we investigated how healthcare professionals allocate their time during their shifts in the ED. We collaborated with a panel of medical experts to discretize the ED plane into subareas, associating specific activities with each subarea (Fig. 1). The activities included care coordination, informatics, transit, care preparation, management, stock, care, cleaning and stock, and other. Care coordination involves the triage nurse office, the welcome desk, and a meeting room used for communication during shift changes from day workers to night workers. Informatics includes three rooms equipped with computers used for administrative tasks. Cleaning and stock relate to storage rooms with access to a sink for cleaning medical equipment. Care includes the critical care unit, treatment rooms, and medical imaging unit. Additionally, a mixed area has been designated Transit/Informatics/Care, representing a large corridor in the short-stay hospitalization unit where minor care can be administered and administrative tasks are carried out on mobile computers. Based on this classification of activities, we first calculated the proportion of time allocated to each activity for each type of medical staff separately.

The following categories of activities are considered: care, care preparation, care coordination, transit, informatics, mixed area of transit/informatics/care, and other.

Second, activities were categorized into care-related activities and other activities based on two definitions, namely, the lower and upper bounds. This categorization aimed to emphasize the proportion of time dedicated to care. In the lower bound, care-related activities included care, care coordination, and care preparation. In the upper bound, the mixed area of transit/informatics/care was also included.

Finally, we investigated whether healthcare professionals’ time allocation could be impacted by ED crowding. To that end, we estimated a fractional multinomial logit model of the time allocation proportions on patient loads, categories of healthcare professionals, and interaction terms between the two21. This type of model, estimated by quasi-maximum likelihood, is an extension of the traditional multinomial logit model, allowing the dependent variable to be composed of fractions summing to one. To facilitate the estimation procedure, we considered the following categories of activities: lower bound care-related activities (including care, care preparation, and care coordination); transit; informatics; mixed area of transit/informatics/care; and others (including stock, cleaning and stock, management, and other). To account for potential correlations among observations from the same tag, standard errors were adjusted for tag clusters, allowing for intracluster error correlation.

Analysis of walking distance

We used data on tag locations to calculate the hourly walking distance (in meters) by computing the Euclidean distance between points of the same tag and aggregating the resulting data per hour. Considering planar coordinates, the Euclidian distance (i.e., as the crow flies) between two locations with coordinates (({{{{rm{x}}}}}_{1},{{{{rm{y}}}}}_{1})) and (({{{{rm{x}}}}}_{2},,{{{{rm{y}}}}}_{2})) is given with the following formula: ({{{rm{distance}}}}=sqrt{{left({{{{rm{x}}}}}_{2}-{{{{rm{x}}}}}_{1}right)}^{2}+{left({{{{rm{y}}}}}_{2}-{{{{rm{y}}}}}_{1}right)}^{2}}.) We first described the distributions of the hourly walking distance by healthcare professional category.

In the second step, we investigated the correlation between healthcare professionals’ hourly walking distance and patient loads. We estimated a pooled ordinary least squares regression of the hourly walking distance on a set of predictors22. The explanatory variables included hourly patient load, dummy variables for the healthcare professional’s category, and interaction terms between patient load and healthcare professional’s category. To account for potential correlations among observations of the same tag, standard errors are adjusted for tag clusters, allowing intracluster error correlation. Based on the parameter estimates of the model, we conducted a set of predictions to substantiate the variation in walking distance according to patient load.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Tag user label recognition algorithm

During the study period, a total of 16,413,096 timestamped indoor coordinates, grouped into 315 sequences, were recorded by the 28 tags. Among them, all types of medical staff were well represented, except triage nurses, who had a low participation rate (see Supplementary Table 1). The average duration of a sequence was 12.09 h, corresponding to the duration of a shift for most medical staff. Table 1 displays the performance of the random forest classification algorithm according to the size of the hexagonal grid and the feature selection procedure. The target variable is the type of medical staff (e.g., doctor, assistant nurse, triage nurse), and the predictive feature is the proportion of time spent in each hexagon of the grid. The best-performing specification of the model used a hexagonal grid with hexagons with a diameter of 1.75 m, and the 51 most important features were selected based on their impurity score (i.e., Gini coefficient). With this specification, one can predict the type of medical staff with an accuracy of 96.2% based on the patterns in their movements within the ED. To further illustrate the performance of the best-performing algorithm, the confusion matrix is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Time allocation and patterns of healthcare professional movements within the ED

Table 2 provides an overview of how healthcare professionals allocated their time during their shifts at the ED. On average, doctors and on-duty doctors spent 26% and 33%, respectively, of their time in care-related activities under the lower bound definition, compared to 39% under the upper bound definition. Waiting room nurses and SSU nurses allocated one-third to two-thirds of their time to care-related activities, in the lower and upper bounds, respectively. Interestingly, the range between the lower bound and the upper bound varied substantially among healthcare professional types, primarily due to the proportion of time spent in the mixed area of transit/informatics/care. For example, the share of time spent in care-related activities did not vary much between the bounds for triage nurses and ICU nurses, with almost half of their time dedicated to care-related activities. In contrast, the share of time spent in care-related activities varied from 26% to 57% for assistant nurses.

See Supplementary Fig. 1 for information about the proportions of time dedicated to all subcategories of activities. Overall, the burden of non-care-related activities is largely induced by administrative duties and transit. This is especially relevant for doctors and on-duty doctors, who spend approximately one-third of their time in transit and a quarter of their time on administrative duties.

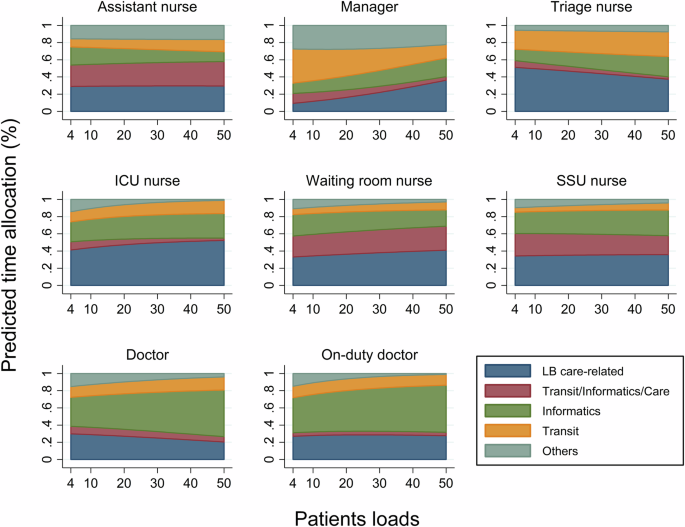

Finally, the results of the fractional multinomial logit model investigating the impact of patient loads on time allocations are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Based on the parameter estimates of the model, we conducted a set of predictions regarding healthcare professionals’ allocation of time, conditional on patient load (Fig. 2). We considered patient loads ranging from the minimum to the maximum values observed in the data (e.g., from 4 to 50 patients).

The following categories of activities are considered: lower bound (LB) care-related activities (including care, care preparation, and care coordination); transit; informatics; mixed area of transit/informatics/care; and others (including stock, cleaning and stock, management, and other). Patients loads refers to the hourly number of patients in the emergency department. Types of medical staff are classified into assistant nurses, triage nurses, intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, waiting room nurses, short-stay unit (SSU) nurses, managers, doctors and on duty doctors.

For assistant nurses, the time spent on care-related activities (including care, care preparation, and care coordination) and other activities (including stock, cleaning and stock, management, and other) was generally invariant to patient load. However, they reduced their time spent in informatics areas (by a maximum of 11 percentage points (pp)) and allocated more time to transit and the mixed area of transit/informatics/care as the patient load increased. For triage nurses, higher patient loads decreased the proportion of time spent in care-related areas (by a maximum of 15 pp) and in the mixed area (by a maximum of 6 pp), leading to more time in transit, informatics, and other areas. Interestingly, for ICU and waiting room nurses, the time spent in care-related areas increased with ED crowding, by a maximum of 13 pp and 9 pp, respectively. This increase was accompanied by reduced time spent in informatics and other activities for waiting room nurses and reduced time in mixed areas and other activities for ICU nurses. The time allocation for SSU nurses was rather homogeneous, regardless of patient load, except for a slight shift in time from the mixed area to the informatics area when crowding increased. Finally, the burden of administrative duties substantially increased along with patient load for doctors and on-duty doctors, by a maximum of 22 pp and 16 pp, respectively. On-duty doctors counterbalanced the increased time in informatics by reducing their time in other activities (by a maximum of 16%). Note that they counterbalanced it such that there was no significant reduction in care-related activities. For doctors, however, this led to a reduction in time spent on other activities of a maximum of 13%, as well as a reduction in care-related activities of a maximum of 10%.

Correlation between walking distance and ED crowding

We observed wide variations in hourly walking distances in the data across and among each type of healthcare professional (Supplementary Fig. 2). Similarly, wide variations were observed in patient incoming flows and patient loads in the ED, showing clear hourly seasonality (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4).

The results from the pooled ordinary least squares regression confirmed that, conditional on patient load, there were significant differences in walking distances across types of healthcare professionals (Table 3). Specifically, assistant nurses (modality in reference), ICU nurses (p = 0.543), waiting room nurses (p = 0.087) and SSU nurses (p = 0.324) had, on average, comparable hourly walking distances, whereas the hourly walking distance was significantly greater for triage nurses (p = 0.005) and lower for doctors (p < 0.001), on-duty doctors (p < 0.001) and managers (p < 0.001). Regarding the impact of patient loads on hourly walking distances, we found a heterogeneous effect across different types of healthcare professionals. Thus, we conducted a Wald test for each category of medical staff, testing the linear constraint that the sum of the coefficients for patient load and the interaction term were significantly different from zero23. The results indicated a positive, significant, and homogenous impact of patient load on walking distance for assistant nurses (p < 0.001), ICU nurses (p < 0.001), waiting room nurses (p < 0.001), and SSU nurses (p = 0.0011). However, we could not reject the null hypothesis for doctors (p = 0.1131), on-duty doctors (p = 0.1171), or triage nurses (p = 0.6228), meaning that the hourly walking distance was independent of patient load.

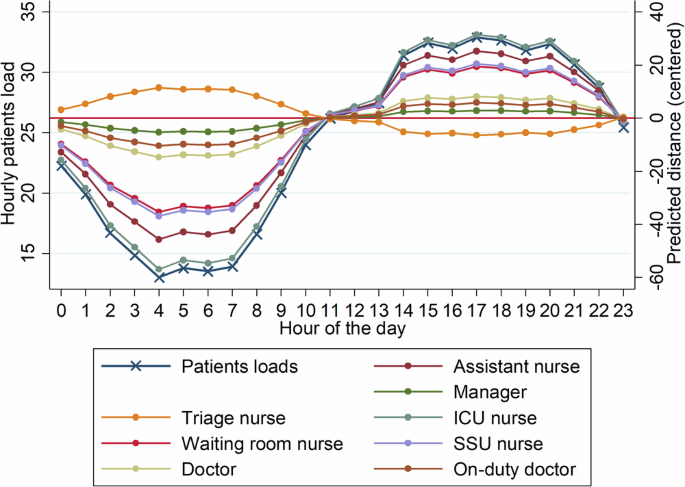

Based on the parameter estimates of the model, we predicted the walking distance during a fictive day, for which we simulated the hourly patient load by taking its average value over the study period (Fig. 3). To highlight the variations in walking distance, the predicted hourly distances were centered on their mean for each healthcare professional category. The predicted hourly walking distances for assistant nurses, ICU nurses, waiting room nurses, and SSU nurses deviated substantially below the mean in the early morning (i.e., when patient loads were the lowest) and above the mean in the afternoon. To gauge the magnitude of the variations, the highest predicted distances (i.e., at 5 PM) were 23%, 29%, 16%, and 18% greater than the lowest distances (i.e., at 4 AM) for assistant nurses, ICU nurses, waiting room nurses and SSU nurses, respectively.

Patients loads refers to the hourly number of patients in the emergency department. Predicted hourly distances are centered on their mean for each healthcare professional category. Types of medical staff are classified into assistant nurses, triage nurses, intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, waiting room nurses, short-stay unit (SSU) nurses, managers, doctors and on duty doctors.

In addition, we explored the size of the area where healthcare professionals operate, referred to as the surface of activity. First, we computed the cumulative time spent in each hexagon of a hexagonal grid over the ED plane. The surface of activity for a sequence of observations was defined as the surface area of the most frequently visited hexagons, where an individual spent 95% of their time. We excluded the less representative hexagons to exclude from the surface of activity areas where individuals might have been only once during their shift. Table 4 displays the average surface of activity for each medical staff category. Interestingly, on average, 95% of a doctor’s activity occurred in an area of 77 m², while an assistant nurse’s activity covered 254 m². These varying sizes of surfaces of activity could provide a first explanation for the substantial differences in hourly walking distance.

We predicted the accumulated distance over an entire shift and computed the ratio of the predicted accumulated distance over the shift divided to the surface of activity (Table 4). This ratio provides insight into the degree of repeated movement or repeated trips, as it represents the average walking distance per square meter of the surface of activity. Interestingly, compared with those in other healthcare professional categories, doctors who were found to have the second-lowest accumulated walking distance had the highest ratio of distance walked relative to their surface of activity.

Discussion

In this study, we experimented with an IPS based on UWB to track healthcare professionals’ activities during their shifts in the ED of a public hospital. We explored and analyzed the large amount of data recorded in quasi-real-time and investigate how tracking systems could provide a better understanding of the process of emergency care production.

The results show the potential of IPS to quantify how healthcare professionals allocate their time during their shifts. A striking result is that the proportion of time spent on care-related activities ranges between 26% and 39% for doctors and between 33% and 39% for on-duty doctors. In contrast, this share reaches approximately half of the time for triage nurses and ICU nurses and ranges between one-third and two-thirds for waiting room nurses and SSU nurses. The burden of non-care-related activities appears to be largely induced by the time spent on administrative duties and transit. As an illustration, doctors and on-duty doctors, on average, dedicate approximately one-third of their time to transit and a quarter of their time to administrative duties. For these two healthcare professional categories, we also found that the burden of administrative tasks increases as ED crowding increases.

These findings highlight significant opportunities for improvement through targeted optimization. To reduce time spent on administrative work and transit, some potential solutions include the integration of user-friendly technology and automated data entry systems, optimizing facility layouts, improving patient and workflow management, redistributing tasks, and providing staff with training in time management and efficiency. Implementing these strategies could substantially reduce non-care-related activities, allowing healthcare professionals to devote more time to patient care. Moreover, recent advances in large language models (LLMs) and natural language processing (NLP) offer a promising tool for further reducing the time spent on documentation by automatically summarizing clinical notes, medications, and other forms of patient data. However, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare also raises important ethical considerations that must be carefully addressed24,25.

Several studies have investigated medical staff time allocation, mostly through the use of qualitative research methods such as shadowing techniques. The principle of shadowing is that the researcher acts as an observer while individuals perform their usual activities26. A German study relied on shadowing to measure the time allocation of interns and surgeons in a general hospital, recruiting 35 participant observations27. They found that an average of 25% of time was spent in direct contact with patients, while the remaining time was mostly allocated to administrative duties and coordination with nursing staff. A Norwegian study also employed shadowing to investigate physicians’ time allocation in the context of the production of emergency care, with a focus on drug-related tasks28. The authors’ main finding was that physicians spent the majority of their time gathering information, communicating and documenting, whereas drug-related tasks accounted for 17% of their time. Another study employed shadowing to investigate physician time allocation in two EDs29. They found documentation to be the most time-consuming activity for both physicians and nurses and substantiated that nurses spent significantly more time on therapeutics than physicians did. The strength of shadowing techniques is the ability to observe activities that could otherwise be difficult to measure quantitatively. However, there is a risk of observer bias and the Hawthorne effect30,31. Observer bias occurs when prior beliefs of the researcher influence what they perceive during the observation phase. The Hawthorne effect occurs when participants alter their behavior in response to their awareness of being observed32. In contrast, IPS has the advantage of being less invasive than shadowing, allowing the recording of information on critical care without disturbing the process. IPS also offers the opportunity to obtain real-time information and to track the activity of an individual over a long period. This approach, for example, allowed us to investigate how different levels of ED crowding affect the results.

In the literature, a few studies have experimented with the use of IPS to track healthcare professional activity. A recent study proposed a context-free localization approach to visualize and analyze IPS data by encoding sequences of observations as time-encoded strings33. The strength of their approach is to be context-free, in the sense that no prior information on the building and the activities conducted in each room is required. In comparison, our approach relies on the expertise of a panel of medical experts to discretize the ED plane into subareas, associating specific activities with each subarea. The added value of our framework is to directly exploit a time series of coordinates, allowing us to investigate the correlation of time allocation with time-dependent variables (e.g., ED crowding), as well as to delve into walking patterns. In the study of Stisen et al., a Wi-Fi tracking system was used as a monitoring tool to detect in which phase of activity a medical staff member is involved, as well as the estimated time remaining to complete the task15. Using an RFID IPS, Castner and Suffoletto measured clinician‒patient contact time and the number of encounters per visit and showed that it became more fragmented as ED crowding increased16. In comparison, in this study, we investigated healthcare professionals’ time allocation over their entire shift, including both care and non-care-related activities. To do this, we relied on a UWB tracking system, which has been shown to provide much greater accuracy than continuous-wave IPS such as Wi-Fi or RFID8. In addition, we developed an algorithm capable of predicting the type of healthcare professional based on the patterns of movements within the ED with an accuracy of 96% (Table 1). This model could be particularly useful for detecting whether a nurse is currently working as a triage nurse, ICU nurse, waiting room nurse, or SSU nurse. In fact, nurses can switch multiple times per day from one category to another. Switches are not always scheduled and can be the result of exceptional circumstances such as sick leave or unexpected ICU admissions.

We also measured healthcare professionals’ walking distances and investigated their correlation with ED crowding. Interestingly, the hourly distance walked by nurses (except triage nurses) increases as the ED becomes crowded, while for doctors, the walking distance is invariant to patient load. In the literature, physicians’ walking distances have been traditionally measured using pedometers34. While pedometers have shown good performance in predicting the number of steps and distance traveled during activities such as running with a structured gait, they have been shown to provide poor accuracy in predicting distances in indoor environments with unstructured gaits35. Thus, IPS could also provide an alternative to pedometers and has the advantage of being unaffected by gait structure. Moreover, IPS data allow walking distance to be related to the surface of activity. For example, we found that doctors, who were found to have the second-lowest accumulated walking distance, have the highest ratio of distance walked relative to their surface of activity, compared to other healthcare professional categories. This ratio highlights the fact that doctors are highly mobile workers but in a smaller surface of activity compared to other healthcare professional categories.

IPSs provide new perspectives for identifying organizational issues and assessing the real-world performance of interventions aimed at reorganizing EDs by turning positional data into key-performance indicators (e.g., time allocation, surface of activity, etc.)36. In this context, the development of digital twins, capable of offering a virtual representation of a physical system in real-time, is at the heart of healthcare research37. However, its large-scale applications remain limited, due to the technological and economic obstacles to setting up real-time data collections38. In this aspect, IPSs are a promising technology that can be used to collect real-time signals on patients and/or workers, which is required to implement digital twins. In addition, IPSs also open new perspectives to help in the conception of digital twins, offering an alternative source of data for generating event-logs and delving into process mining and process discovery to identify and analyze patient care pathways39,40.

The results of this study must be interpreted in conjunction with the following limitations that can be used to inform future studies. First, the approach used for activity recognition relies on the discretization of the ED into subareas for which a specific activity can be associated. While being a powerful approach to identifying the time dedicated to care as the time spent in treatment rooms, interpreting locations falling into transit areas is more challenging. Indeed, the time spent in transit areas is also likely to be used for a combination of different activities, such as transiting and communicating with other clinicians. The same limitation applies for the SSU corridor designated as transit/informatics/care, where minor care can be administered and administrative tasks are carried out on mobile computers. This drawback could be lessened in future IPS experiments by detecting interactions between people and by adding more sensors, for example, on patients and/or assets (e.g., tracking of mobile computers). This study benefits from a high participation rate among most medical staff, with the exception of triage nurses, whose participation was low. As a result, findings related to this specific group should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, since this study was conducted at a single location, its generalizability to other hospitals may be limited. However, we believe that the proposed methodology is broadly applicable and can be easily adapted to different settings. Lastly, while IPS based on radio frequency signals offers high accuracy, indoor environments often introduce noise due to their complexity. To mitigate this, we implemented a smoothing algorithm that aggregates data into time windows, which demonstrated strong performance.

In conclusion, the development of indoor tracking systems opens new perspectives for the analysis of the process of emergency care production. The IPS based on UWB used in this study demonstrated its potential to quantify healthcare professionals’ time allocation and walking distances during their shifts. We found wide variations in time allocation among different healthcare professional categories. Overall, the burden of non-care-related activities appears to be largely induced by the time spent on administrative duties and transit. ED occupancy is found to have a heterogeneous impact on time allocation and walking distance according to the category of clinician.

Responses