Infected wound repair correlates with collagen I induction and NOX2 activation by cold atmospheric plasma

Introduction

Cutaneous wound repair is a complex physiological process aimed at restoration of skin homeostasis. Bacterial wound infection is a common complication, which compromises wound healing by damaging the epidermal and dermal cell lineages. Opportunistic pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus are known to act either as an asymptomatic commensal or pathogenic colonizer of wounds, particularly in the context of extensive breaches of protective skin barrier1,2,3,4. Local replication of S. aureus within the cutaneous wound may lead to its dissemination via the bloodstream from the primary focus of infection to distant sites giving rise to potentially life-threatening systemic complications1,5.

Complex epithelial-immune cell communication2,6, triggered by bacterial by-products and other cues, results in activation of tissue-resident7 and blood-derived macrophages recruited to the site of wound infection8. Killing of S. aureus by macrophages is mediated by several mechanisms, including the concerted actions of reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced upon activation of phagocyte NADPH oxidase and respiratory burst9,10. The phagocyte NADPH oxidase is a multicomponent enzyme11, composed of catalytic transmembrane subunit NOX2 (alternative names: CYBB and gp91phox), transmembrane protein p22phox, cytosolic subunits p40phox, p47phox, p67phox and Rac9,12,13,14. NOX2 catalyses the production of superoxide (O2−), which is then converted to other downstream ROS, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hypochloric acid (HOCl), and hydroxyl radical (•OH)9,10. Molecular on–off switches such as post-translational modifications of phagocyte NADPH oxidase components, including phosphorylation of p47phox and p40phox, translocation of cytosolic p47phox, p67phox and p40phox to the phagocytic cup on the endosomal membrane10, and recruitment of guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound Rac to p67phox lead to assembly of the enzymatic complex14. Once assembled, the active complex generates superoxide by transporting electrons from cytoplasmic NADPH to phagosomal oxygen. The crucial antimicrobial role of ROS production by phagocytes is highlighted by mutations in the CYBB gene15 leading to aberrations in phagocyte NADPH oxidase signaling in patients with chronic granulomatous disease, resulting in impaired killing of pathogens16,17.

Emerging antimicrobial resistance is a global public health threat. In individuals older than 15 years, S. aureus causes more deaths than any other antibiotic-resistant “priority pathogens”18. Among fatality attributable to antimicrobial resistance, more than 100,000 deaths were caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in 201919. Design and development of alternatives, in addition to conventional antibiotics, are thus urgently needed20. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) is a promising technology used to fight disease-causing microbial pathogens, especially in the context of infected cutaneous wounds21,22,23. CAP produces photons, UV radiation, electromagnetic (EM) energy, electrons, ions, and radicals, such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS)22,24,25,26. CAP is generated by applying electrical energy to gas, which becomes weakly ionized27. Typical degree of ionization is low: ne/(nn + ne) < 10−5, where nn and ne are the neutral gas and electron densities, respectively27. The interaction of CAP with liquid water27 is thought to generate aqueous-based antimicrobial formulations comprising a rich mixture of oxidants such as O2−, NO, H2O2, O3, NO2− and NO3 −26,28,29, which together with physical parameters24, including electric field, exert biologically relevant responses. Here, we elucidate a previously unknown mechanism of CAP, which activates NADPH oxidase and correlates with robust bacterial clearance during wound resolution, supporting the use of CAP in the treatment of infected tissue.

Results

CAP stimulates collagen I production and infected cutaneous wound healing

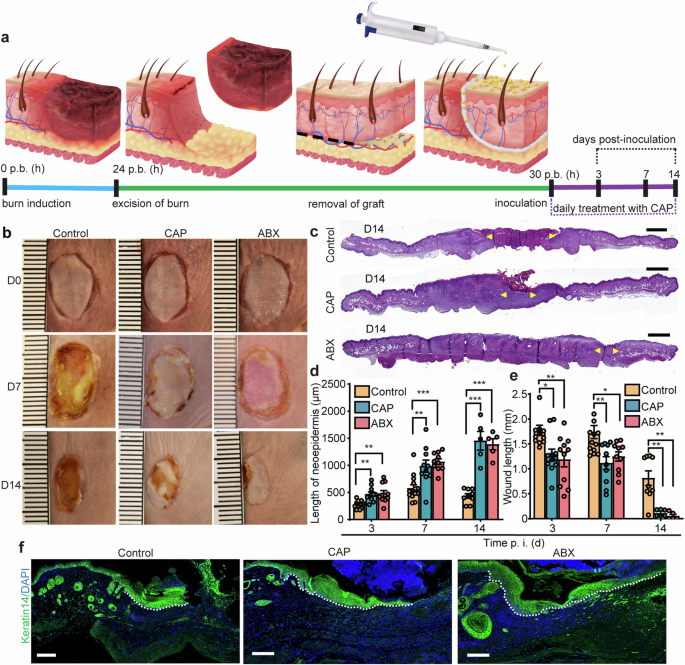

To mimic bacterial infection in a cutaneous wound, we adapted a model previously used in our skin graft integration studies28,30,31. In clinical practice, skin grafts are used routinely to provide coverage for wounds, such as burns32, unlikely to heal by secondary intention33. While individual clinical situation dictates the type of graft to be placed, disruptive effects of S. aureus infection threaten graft survival regardless of the type. Here, we used a reproducible mouse model of burn wound reconstructed with allogeneic skin graft and infected with S. aureus (Fig. 1a). Signs of delayed healing were apparent in wounds treated with placebo control compared to healing of wounds treated with CAP or topical antibiotics (ABX) (Fig. 1b). Day 7 placebo wounds were characterized by dark-brown necrotic tissue visible around the wound margins. Day 7 wounds treated with either CAP or ABX appeared as healthy pale pink, with visible signs of newly formed granulation tissue known to provide temporary matrix in the damaged skin. At 14 d. p. i., staphylococcal wound infection resulted in varying degrees of skin graft survival depending on the applied treatment (Fig. 1b). Control treatment resulted in complete loss of the graft by 14 d. p. i. (Fig. 1b). In contrast, macroscopic appearance of wounds treated with either CAP or ABX showed signs of improved graft survival following infection compared to time-matched control at 14 d. p. i. (Fig. 1b).

a Experimental outline of mouse wound healing assay. Burn wounds were grafted, inoculated with S. aureus, and treated either with placebo control, CAP or mupirocin (ABX). Created with Adobe Illustrator. b Representative images of grafted mouse burn wounds from two independent experiments. Scale, 1 mm. c H&E-stained wounds at 14 d. p. i. Yellow arrows indicate margins of the microscopic wound length. Scale, 1 mm. d The length of neoepidermis at 3, 7 and 14 d. p. i. Per order in the bar graph, n = 12, 14, 9 for control, n = 11, 10, 5 for CAP and n = 11, 10, 5 for ABX groups, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 versus control. Exact p are reported in Supplementary Data 1. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. e Microscopic wound length. n = 12, 14, 9 for control, n = 11, 10, 5 for CAP and n = 11, 10, 5 for ABX groups, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus control. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. Data represents mean ± s.e.m from two independent experiments. f Representative images of wounds (7 d. p. i.) immunolabeled with keratin 14 (green). Dotted line demarcates the advancing neoepidermis. Scale bars, 100 µm. p. b. (h) post-burn (hours), CAP cold atmospheric plasma, ABX antibiotics, d. p. i. days post-inoculation, time p. i. (d) time post-inoculation (days).

At microscopic level, histological wound assessment showed that indicators of successful skin engraftment were markedly improved in infected wounds treated with CAP or ABX compared to placebo control (Fig. 1c–f). The microscopic wound length of CAP or ABX-treated wounds was significantly reduced compared to control at 14 d. p. i. (Fig. 1c, e). Additionally, the lengths of neoepidermis at 3, 7 and 14 d. p. i. were increased upon CAP or ABX treatments compared to control treatment (Fig. 1d, f).

Immediately after wound colonization, bacterial by-products, damage signals and chemoattractants trigger multiple responses, including the infiltration of immune cells to the site of infection10,34,35. Our previous studies28,30 showed that CAP generates a range of oxygen and nitrogen derivatives (Supplementary Fig. 1) similar to those produced by wound leukocytes6. We, therefore, hypothesized that these biochemical molecules may act either as signals or chemoattractants to immune cells. This hypothesis prompted us to assess the immune cell infiltrate in wounds. Five different antigens, commonly known to be expressed by wound leukocytes, were probed to assess the profile of cells trafficked to the site of infection. Wounds were immunostained with anti-CD45 antibodies—a cell-surface protein detected on most lymphohematopoietic cells35,36. No significant difference was detected in the number of infiltrated CD45+ wound leukocytes between control, CAP and ABX-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). We next investigated the expression of genes encoding chemotactic TNF-α, inflammatory IL1-β and NOS2, growth factors VEGF-α, PDGF-β and growth factor receptor TGF-β receptor-1—mediators involved in the cascade of innate immune cell recruitment in infectious inflammation7,34,37. No statistically significant difference was detected in the mRNA levels (placebo control versus CAP-treated wounds) of these genes, including Pdgfb—encoding an established macrophage and neutrophil chemoattractant38 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). In comparison to placebo control neither CAP nor ABX-treated wounds showed significant differences on the magnitude of innate immune cell infiltrate, including cells positive for F4/80 (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e), NAG (Supplementary Fig. 2f)—both expressed by murine macrophages39,40, CD206 (Supplementary Fig. 2g, h) transmembrane protein abundant in tissue macrophages displaying an M2-like phenotype41, Ly6G (Supplementary Fig. 2j, k) and MPO (Supplementary Fig. 2i, l, m)—markers of neutrophils42,43. Treatment with CAP resulted in a faster healing of infected wounds compared to placebo treatment but failed to stimulate neutrophil and macrophage accumulation. We conclude that promotion of tissue repair by CAP depends on mechanisms other than recruitment of innate immune cell populations.

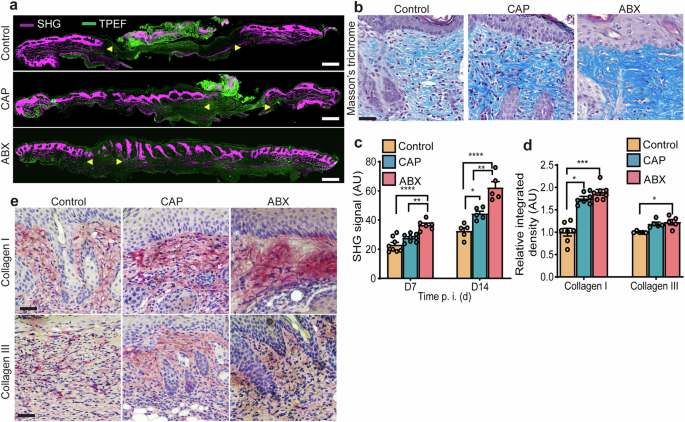

To further assess the wound environment and skin composition in response to CAP treatment, we studied the extracellular matrix (ECM) — a network of fibrous and non-fibrous molecules that surround, support, and give structure to resident cells. We, therefore, assessed the in vivo level of fibrillar collagen I protein—a major structural component of ECM with a prominent functional role in wound healing and tissue regeneration (Fig. 2a). Here, we provide two lines of evidence suggesting that CAP stimulates the production of collagen I in the ECM. First, label-free imaging of fibrillar collagen I (second harmonic generation) and histological staining of collagen fibers (Masson’s trichrome) showed a significantly increased deposition of fibril-forming collagen I in wounds treated with CAP or ABX compared to control (Fig. 2a–c). Second, chromogenic detection of protein expression in wounds indicated that the principle source of tensile strength in the skin—collagen I (triple helix with two α1 and one α2 polypeptidic chains44) was significantly increased in wounds treated with CAP or ABX (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Fig. 3d). The levels of collagen III (triple helix with three α1 polypeptidic chains44), characterized by thin fibers and, consequently, insufficiently adequate skin strength45, remained unchanged in wounds treated with CAP, but significantly elevated in ABX-treated wounds compared to control (Fig. 2d, e). Along these lines, CAP significantly increased expression of COL1A1, but not COL3A1 mRNA in non-infected, scratch-wounded fibroblasts in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f).

a Two photon microscopy (wounds at 14 d. p. i.). Yellow arrows indicate wound margins. Scale bar 1 mm. b Masson’s trichrome and collagen SHG (14 d. p. i.). Scale bar 20 μm and 100 μm. c collagen SHG signal (wounds at 7 and 14 d. p. i.). n = 8 for control, n = 8 for CAP and n = 6 for ABX for day 7; n = 5 for control, n = 5 for CAP and n = 5 for ABX for day 14. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 versus control. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. d Quantitative microdensitometric evaluation and e representative images of wounds stained for collagen I and III (7 d. p. i.). n = 7 for control, n = 7 for CAP and n = 7 of ABX, *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 versus control. Scale bar 25 µm. Exact p are reported in Supplementary Data 2. AU arbitrary units, CAP cold atmospheric plasma, ABX antibiotics, SHG second harmonic generation, TPEF two-photon excited fluorescence, time p. i. (d) time post-inoculation (days).

Other key components of ECM44,46, including laminin and collagen IV were synthesized in significantly higher levels in the vicinity of wounds treated with CAP compared to control (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). Taken together, our results show that wound healing upon CAP treatment correlates with enhanced production of ECM proteins and, most notably, synthesis of collagen I in infected wounds in vivo and in non-infected wounds in vitro.

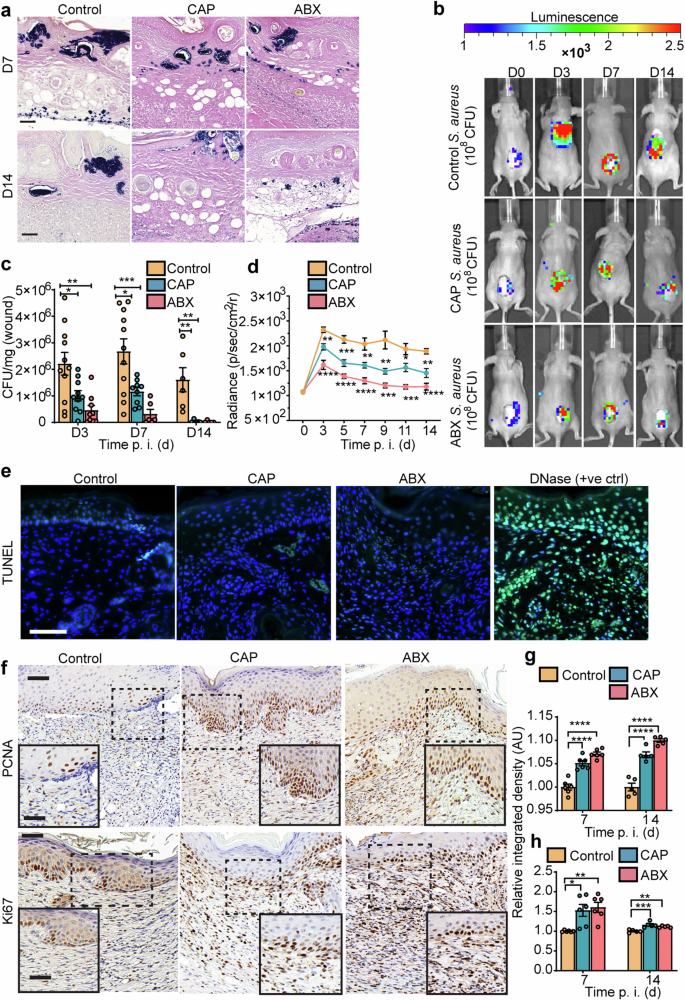

CAP promotes resolution of skin wound infection

Given our previous report establishing anti-staphylococcal properties of CAP25, we hypothesized that CAP treatment could reduce the number of S. aureus infecting skin wounds. We, therefore, compared the bacterial burden of infected wounds treated with either helium control, CAP or ABX (Fig. 3a–d). Microscopic Gram stain analysis of day 7 wounds, in all three experimental groups, showed bacterial clusters localized to epidermal, dermal, and hypodermal compartments of the skin (Fig. 3a). However, these clusters were larger in control mice. Bacterial burden upon CAP or ABX-treatment decreased from day 7 to day 14, at which point it remained much smaller than upon control-treatment. Similarly, fewer bacteria were detected in mice treated with CAP and ABX compared to control at day 7 and day 14, but also at the earlier time point of 3 d. p. i. (Fig. 3c). Real-time bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of S. aureus in living mice, demonstrated that daily treatment with CAP or ABX effectively reduced bioluminescent signal over a course of 14 days following infection compared to time-matched control wounds (Fig. 3b, d). BLI measurements positively correlated with quantitative analysis of CFU enumerated in homogenized wounds and showed at least a 50% reduction in bacterial burden of wounds treated with CAP compared to time-matched control (Fig. 3c, d). Anti-staphylococcal activity of CAP did not compromise the host DNA integrity as indicated by the TUNEL assay, which showed the absence of signal corresponding to mammalian DNA damage and alarming apoptotic cell death (Fig. 3e). These results are consistent with the analysis of host tissue proliferation (Fig. 3f–h). The number of evidently proliferating PCNA+ and Ki67+ cells was significantly increased in wounds treated with CAP and ABX compared to control (Fig. 3f–h and Supplementary Fig. 4). Overall, our observations showed a decreased bacterial burden and increased cellular proliferation in both CAP and ABX-treated animals compared to placebo-treated wounds.

a Gram stain (mouse wounds at 7 and 14 d. p. i.). Scale bar 20 µm. b Real-time monitoring of S. aureus Xen36 in wounds. c Mouse wound burden (CFU enumeration). d Quantification of S. aureus Xen36 bioluminescence signal. e TUNEL staining (7 d. p. i.). Apoptotic cells (green); DAPI (blue). Scale bar 20 µm. f Representative images (7 d. p. i.) and g quantitative evaluation of PCNA (mitotic marker) and h Ki67 (proliferation marker) in mouse wounds. Enlarged views of the boxed regions are shown in the insets. Scale bar 50 µm; inset 20 µm. In (c) n = 11 for control, n = 10 for CAP and n = 9 for ABX for day 3. Precise number of mice in each group and exact p are reported in Supplementary Data 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus control. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test was used in (c), (d), (g) and (h). Results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. of two independent experiments. CFU colony forming units, ctrl control, CAP cold atmospheric plasma, time p. i. (d) time post-inoculation (days).

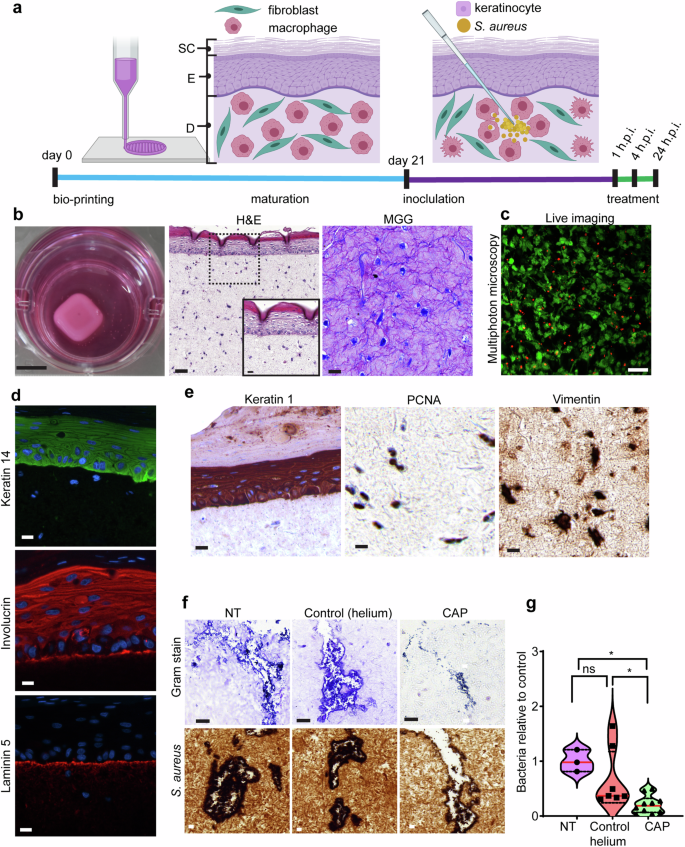

CAP decreases S. aureus infection in a three-dimensional skin wound model

To investigate whether antibacterial property of CAP extends to human pre-clinical models of infection, we used 3D bioprinting techniques, where the number of printed phagocytic and non-phagocytic host cells are effectively controlled. We recapitulated staphylococcal wound infection in bioengineered, macrophage-laden human skin equivalents (Fig. 4a). Microscopic characterization of 3D skin models showed two distinct components: dermis and epidermis with an outermost layer of enucleated keratinocytes—stratum corneum (Fig. 4b). Using markers of plasma membrane integrity and esterase activity we demonstrated that cellular viability is maintained up to 21 days post-printing (Fig. 4c). The epidermal and dermal compartments of bioengineered skin expressed epidermal (keratin 14 and 1) and dermal (vimentin) markers typically present in healthy human skin (Fig. 4d, e). The presence of involucrin and laminin 5 suggests that bioengineered skin models express key markers of functional dermal-epidermal junctions (Fig. 4d). Histological and immunohistochemical assessment of intradermal bacteria, suggested that S. aureus existed in clusters, indicative of its notorious capacity to form biofilm5 communities (Fig. 4f). Inoculation of bioengineered skin with S. aureus resulted in consistent and reproducible infection (Fig. 5g). Significant reduction in the number of live bacteria was associated with CAP treatment compared to 3D skin models that received either no treatment (NT) or placebo treatment (control) (Fig. 4g). CAP reduced the number of live bacteria in macrophage-laden bioengineered skin confirming its antibacterial activity in highly traceable in vitro models of infection.

a Schematic representation of experimental timeline. Bioengineered human skin was matured, wounded and inoculated with S. aureus before treatment with CAP or helium. The experimental timeline is not drawn to scale. Created with BioRender.com. b Macroscopic and microscopic images (H&E and MGG) of bioengineered skin. Enlarged view of the boxed region is shown in the inset of H&E-stained micrograph. Scale bar: macroscopic image 1 cm; H&E-stained (large) 100 µm; inset 20 µm; MGG-stained section 20 µm. c Depth-resolved optical section taken 337 µm deep (z-step: 0.5 µm) into bioengineered skin to image live (calcein, green) and dead (ethidium homodimer, red) cells. Scale bar 50 µm. d Epidermal keratinocytes (keratin 14) and dermal-epidermal junction (involucrin and laminin 5) in bioengineered skin. e Immunohistochemical staining (keratin 1, PCNA, vimentin) of bioengineered skin. Scale bar in (d) and (e) is 20 µm. f Bioengineered human skin inoculated with S. aureus. Gram stain (upper panel) and immunohistochemical staining using anti-S. aureus antibodies (lower panel). Scale bar 20 µm. g Violin plot with mean denoted in red. Bioengineered wounds were analyzed for the number of living bacteria (24 h. p. i). CFU average in NT group was normalized to 1 and compared to other groups. n = 3 for NT, n = 7 for control (helium) and n = 10 for CAP. Absolute CFU values and exact p are reported in Supplementary Data 4. *p < 0.05 versus NT. One-way ANOVA non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test. Results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments. SC stratum corneum, E epidermis, D dermis, h. p. i. hours post inoculation, H&E hematoxylin and eosin, MGG May Grunwald-Giemsa, NT no treatment, CAP cold atmospheric plasma.

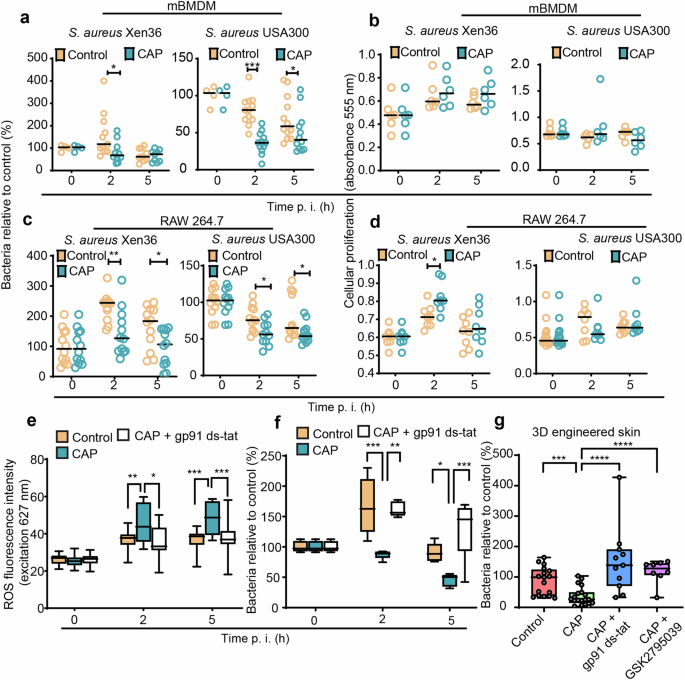

a, b mBMDM and c, d RAW264.7 macrophages were infected with S. aureus Xen36 or S. aureus USA300 and treated with helium (control) or CAP. a, c Cells were lysed at 0, 2, and 5 h. p. i., and released bacteria were counted by CFU enumeration. The effect of CAP treatment on cellular proliferation was measured in b mBMDM and d RAW264.7 macrophages infected with S. aureus Xen36 or S. aureus USA300. e, f RAW264.7 macrophages pre-treated or not with gp91 ds-tat (NOX2 inhibitor), infected with S. aureus Xen36 and exposed to helium (control) or CAP. e ROS production and f relative number of living bacteria in cells. g Three-dimensional bioengineered human skin treated or not with gp91 ds-tat or GSK2795039 (NOX2 inhibitors) was inoculated with S. aureus Xen36 and exposed to helium (control) or CAP. The number of living bacteria was determined by counting CFU at 24 h. p. i. CFU average in control group was normalized to 100. n = 17 for control, n = 19 for CAP, n = 11 for CAP + gp91 ds-tat, n = 8 CAP + GSK2795039. Values are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. In a, c, f time zero average was normalized to 100. For each time point and for each strain, the number of CFU is shown relative to the number of CFU at time zero. Values are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments with at least six biological replicates in each condition. Absolute CFU values, precise number of replicates in each group and exact p are reported in Supplementary Data 5. For a–d significance was determined by Mann–Whitney U test, and e, f by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Anti-staphylococcal activity of CAP is NOX2-dependent

Wound macrophages represent a diverse population of immune cells with heterogeneous functions including detection, ingestion, and digestion of invading microorganisms at sites of infection7,47. Staphylococcal skin infection drives monocytopoiesis, whereby bone marrow promonocytes are mobilized, and consecutively recruited from the circulation into infected tissues8,48. Given the importance of macrophages in containing infection, we next investigated the effect of CAP on the ability of murine macrophages to kill S. aureus. Our results showed that treatment with CAP following infection with two different strains of S. aureus, including USA300—a major MRSA strain that spread globally in both community and healthcare settings, leads to a significantly reduced number of intramacrophagic bacteria without compromising the proliferative activity of murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (mBMDM) and RAW 264.7 (Fig. 5a–d). Interestingly, CAP induced a significant increase in the de novo production of intracellular ROS by macrophages compared to control (Fig. 5e).

We next addressed the effect of CAP on phagocyte NADPH oxidase, a major source of ROS in macrophages, using complementary pharmacological and genetic inhibition approaches. Highly effective NOX2 inhibitor gp91 ds-tat49 is a chimeric peptide linked with the tat peptide sequence from human immunodeficiency virus, which facilitates entry into cells. Having a high affinity for the gp91phox, gp91 ds-tat peptide was tested for specificity to inhibit NOX2 and proven to reduce ROS production in a dose-dependent manner in neutrophils49 and macrophages infected with S. aureus50. Addition of two pharmacological inhibitors of NOX2 (gp91ds-tat and GSK2795039) to macrophages, followed by bacterial infection and treatment with CAP, brought down the levels of intracellular ROS and caused it to become comparable to infected macrophages treated with placebo control (i.e., helium) (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Strikingly, NOX2 inhibitor abrogated the antibacterial effect of CAP in both 2D and 3D models of bacterial infection (Fig. 5f, g and Supplementary Fig. 5b). Macrophage transfection with siRNA targeting the Cybb gene (encoding gp91phox—the major component of NADPH oxidase complex) (Supplementary Fig. 5c), followed by CAP treatment, showed reduced intracellular ROS production (Supplementary Fig. 5d) and significantly increased the number of live intramacrophagic bacteria compared to macrophages transfected with control siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Together, our results indicate that CAP modulates macrophage effector responses by stimulating the production of bactericidal oxidants through NOX2 pathway, which contributes to antibacterial effects of CAP.

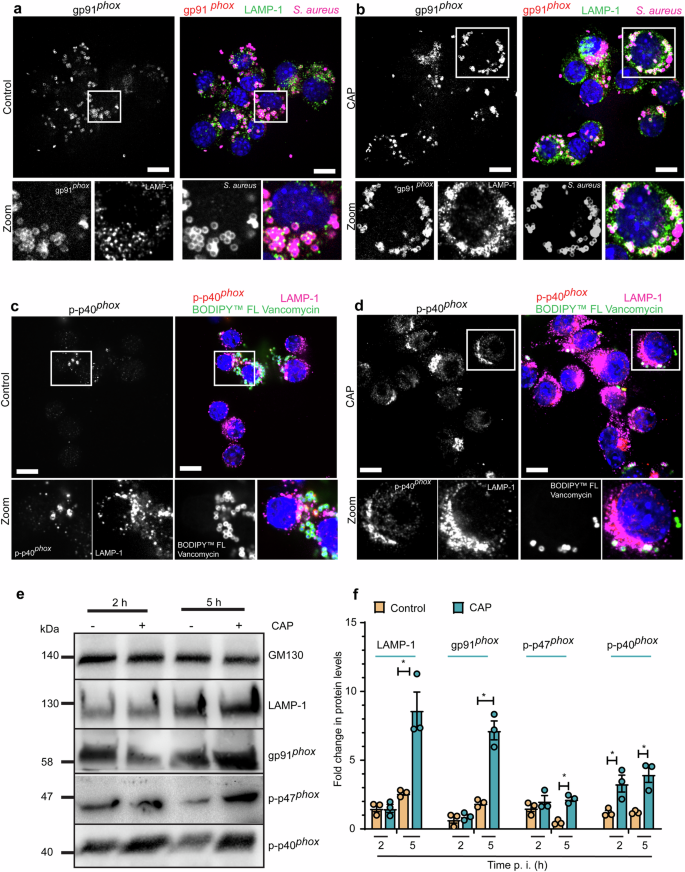

CAP induces NADPH oxidase subunits gp91phox, p-p40phox, p-p47phox and Rac-GTP

Since the presence of functional catalytic subunit gp91phox and post-translational modification of p40phox and p47phox via phosphorylation are necessary for NOX2 activation, we next determined the percentage of association between phosphorylated subunits of this superoxide-generating enzyme and vacuole-bound bacteria in infected macrophages. Treatment with CAP was associated with a higher percentage of colocalisation between vacuole-bound S. aureus and membrane-bound gp91phox, which also coincided with significantly increased levels of phosphorylated p40phox at 5 h. p. i. (Fig. 6a–d and Supplementary Figs. 6e and 7c, d). We subsequently determined the levels of gp91phox, phosphorylated p40phox and phosphorylated p47phox in whole cell lysates extracted from CAP-treated macrophages and compared them to control at both 2 and 5 h. p. i. (Fig. 6e). The level of gp91phox, phosphorylated p40phox and phosphorylated p47phox proteins was significantly increased in the whole cell lysates in response to CAP compared to control (Fig. 6f), which suggests activation of NOX2 enzyme complex.

a–d RAW264.7 macrophages were inoculated with S. aureus (MOI = 10), exposed to helium (control) or CAP and fixed with PFA at 5 h. p. i. Representative confocal microscopy images. a, b The different colors indicate the following: gp91phox (red), S. aureus (magenta), LAMP-1 (green), and DAPI (blue). c, d The different colors indicate the following: p-p40phox (red), LAMP-1 (magenta), BODIPYTM FL Vancomycin-positive S. aureus (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 µm. Zoomed in views of the boxed regions are indicated. e RAW264.7 were infected with S. aureus (MOI of 10), exposed to helium (control) or CAP and collected at 2 and 5 h. p. i. Whole cell lysate extracts were immunoblotted with LAMP-1, gp91phox, p-p47phox and p-p40phox antibodies. GM130 was used as a loading control. f Bar graph showing the fold change in protein levels. Values are means ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments with at least three biological replicates in each condition. Two-tailed paired Student’s t test (control versus treatment). Exact p are reported in Supplementary Data 6. *p < 0.05. WCL whole cell lysate, PFA paraformaldehyde, CAP cold atmospheric plasma.

Our previous studies demonstrated that CAP is a positive modulator of phagolysosomal LAMP-125. Current results confirm that the level of LAMP-1 protein was significantly increased in total cell lysates extracted from infected macrophages treated CAP in comparison to macrophages treated with placebo control (Fig. 6e, f and Supplementary Fig. 8a–d). Taken together, our findings suggest that CAP leads to activation of ROS-yielding NADPH oxidase signaling through induction of its subunits and assembly of gp91phox and p-p40phox at the phagolysosomal membrane.

The superoxide-generating phagocyte NADPH oxidase consists of two membrane-bound and four cytosolic components9,11. Translocation of inactive Rac bound to guanosine diphosphate (GDP) or Rac-GDP from the cytoplasm to the phagolysosomal membrane where it associates to NADPH oxidase subunits in its active guanosine triphosphate (GTP) bound form or Rac-GTP, favors the conversion of NOX2 from the resting to the active state13. Given that NOX2 remains inactive unless activated Rac-GTP assembles at the phagolysosomal membrane, we investigated whether CAP influences Rac-GTP at LAMP-1+ membranes. We quantified the percentage of association between S. aureus trapped in LAMP-1+-bound vacuoles and membrane-bound Rac-GTP in murine macrophages. Our confocal microscopy experiments revealed that although the percentage of colocalization between total Rac (active and inactive) and S. aureus-containing vacuoles remained unchanged, the level of colocalisation with Rac-GTP (active form) was significantly increased in macrophages treated with CAP compared to control (Supplementary Figs. 6a–e and 7a, b). Macrophages infected with S. aureus and treated with either placebo control or CAP were subjected to subcellular fractionation and isolation of membrane-bound intracellular phagolysosomes. Protein extracts from phagolysosomes containing Rac were incubated with antibodies to Rac-GTP bound to magnetic protein G beads. Coimmunoprecipitated protein extracts from phagolysosomes were immunoblotted for Rac and results confirmed that Rac-GTP antibody was able to immunoprecipitate Rac-GTP in phagolysosomes of macrophages treated with CAP, but not in samples treated with placebo control (Supplementary Fig. 6f). The presence of active GTP-bound Rac in phagolysosomes isolated from CAP-treated macrophages further confirms that CAP favors activation of Rac—a prerequisite for the fully functional NOX2 enzyme complex9,13 (Supplementary Fig. 6f).

Discussion

Wound re-epithelialization is the cornerstone of cutaneous tissue repair—a process largely dependent on keratinocyte migration. Here, we combined a biocompatible gas with electrical energy to produce CAP and showed that this therapeutic intervention positively influences the process of wound resurfacing. Indeed, our results demonstrate that treatment with CAP leads to a massive recruitment of keratinocytes from the adjacent epidermis leading to effective re-epithelialization and rapid wound closure in mouse wounds. This is consistent with previously reported animal studies51,52 and recently documented trials showing that CAP promotes wound healing in patients with diabetes mellitus23 and reduces economic burden of clinical wound infection by 50%53. Our own observations identified CAP as a positive regulator of epidermal migration in a two-dimensional model of scratch-wounded cells30, suggesting that CAP provides necessary stimuli that drive cell migration. A biological phenomenon in the form of extensive crosstalk between wound keratinocytes and ECM-producing dermal fibroblasts54, may also be attributed to the positive effect of CAP on cellular migration and wound re-epithelialization. Here, we provide evidence that CAP enhanced the expression of collagen I, collagen IV and laminin—crucial ECM proteins46 in mouse wounds. In addition, we show that non-infected fibroblasts treated with CAP have significantly increased levels of COL1A1 mRNA suggesting that dermal fibroblasts are activated by CAP to synthesize collagen I. This is in agreement without our previously published work, which demonstrated the positive effect of CAP on collagen I protein expression in non-infected wounds both in vitro and in vivo30. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that enhanced cellular migration and wound re-epithelialization resulted from direct effect of CAP on collagen I synthesis and positive influence of CAP over dermal fibroblasts known for their function to synthesize collagen I. This hypothesis is based in one part, on our present study, which demonstrated that CAP enhanced the expression of COL1A1 in human fibroblasts and in the dermis of mouse wounds, particularly during the proliferative phase of wound healing, and in another part, on our previous studies, which showed enhanced expression of dermal-epidermal junction proteins in wounds treated with CAP30. Arndt et al. demonstrated that CAP upregulated TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 gene expression in dermal fibroblasts52. Similarly, our previous studies identified that CAP drives activation of canonical TGF-β1/SMAD signaling pathway in dermal fibroblasts30, known to positively regulate the synthesis of collagen I—major mechanical component of cutaneous ECM. We suggest that collagen-producing dermal fibroblasts are activated by CAP to synthesize collagen-rich skin ECM, especially during the critical proliferative phase of wound healing.

Timely closure of cutaneous wounds is correlated with susceptibility to infection—a major challenge within the clinical setting5,32,33. Here, we report significantly reduced bacterial wound burden, together with strikingly early anti-staphylococcal effects of CAP in infected mouse wounds, which is consistent with previously reported antibacterial effects of CAP in randomized controlled trials21,53,55. The use of CAP in clinical medicine is still in an exploratory, development stage. Wound heterogeneity is a limitation factor in clinical studies, whereas in pre-clinical studies, such as the one presented here, wounds are homogenous and baseline characteristics, such as the original wound size and initial bacterial load are effectively controlled. In our effort to decipher a mechanism that convincingly explains the pro-healing effect, on one hand, and anti-staphylococcal action of CAP, on the other hand, we demonstrated that antibacterial effect of CAP coincides with significantly increased levels of collagen I in the dermis, which may be explained by reduced exposure of these wounds to secreted bacterial virulence factors. Collagen III and fibronectin are actively deposited during the early stages of wound repair46. During the later stages of skin repair, collagen III, which is highly expressed in the granulation tissue is replaced by the skin’s most abundant protein collagen I44,46. In infected skin, mammalian collagens are potential substrates for staphylococcal virulence factors, which degrade structural proteins that serve as a scaffold for the assembly of the skin ECM5,56. Staphylococcal virulence factors fibronectin-binding protein A (FnBPA and FnBPB) and collagen adhesin (Cna) bind to mammalian fibronectin and collagen, respectively, to invade skin5. Although staphylococcal adhesin FnBPB was shown to compromise endogenous fibronectin polymerization57 our current studies of CAP did not detect significant difference in the in vivo expression of fibronectin—component of the provisional matrix during wound repair46. Here, we show that there exists a causal relationship between the number of live bacteria, fibrillar collagen I and non-fibrillar collagen IV levels in infected wounds. This important evidence suggests that CAP-treated wounds with reduced bacterial burden are less vulnerable to degrading action of staphylococcal proteins that break up collagen into peptide fragments, which may seriously hinder the formation of new ECM during wound healing. Interestingly, a causal relationship between collagen I and NOX2 was demonstrated in siRNA knockdown studies involving dermal58 and cardiac59 fibroblasts suggesting that functioning NADPH enzyme is required for collagen I synthesis. Together, our in vivo results suggest that, in infected mouse wounds, CAP therapy accelerates wound closure via reducing bacterial wound load and enhancing new ECM formation.

The role of macrophages in wound angiogenesis60 and inflammation is integral61 and depletion studies are a testimony to the theory that this cell type is vital for host-protective antibacterial responses10,62,63,64. Together with neutrophils, macrophages engulf extracellular bacteria and activate adaptive immune responses7,10. To gain a fuller picture of how CAP may act on wound inflammation and macrophage recruitment, we analyzed the number of F4/80+ macrophages at the infected wound site over a period of 14 days post-infection. Our studies showed no significant difference between the number of macrophages recruited to CAP-treated mouse wounds compared to control, suggesting that CAP does not amplify macrophage trafficking to the site of infection. Apart from phagocytic functions at the site of infection, macrophages orchestrate tissue repair events through their capacity to change phenotype37,47. Our previous in vitro analysis of macrophage-specific proteins25, and present in vivo studies of mouse wound inflammation, suggest that CAP has no influence on phenotypic changes of innate immune cells. The antibacterial effect of CAP in vivo is likely to be due to factors other than changes in macrophages or the sheer multitude of available phagocytic cells at the site of infection. Although neutrophils account for more than half of all leukocytes in the human peripheral blood, they are rarely observed in microscopic sections of normal human65 and naïve mouse skin35, but are recruited in high numbers to the tissue injury site. Monocytes, on the other hand, represent less than one tenth of all leukocytes in human peripheral blood. Nevertheless, skin-resident macrophages are detected in uninjured postnatal mouse skin as determined by spatiotemporal studies66, in high abundance in injured (aseptic)35,67 and infected (septic) cutaneous wounds8,10.

Given that control and CAP-treated mouse wounds had a similar number of phagocytic macrophages and neutrophils, in contrast to a strikingly different number of live S. aureus (CAP reduced bacterial wound burden by at least 50%), we provide mechanistic evidence, which explains how macrophages treated with CAP become more efficient in bacterial killing than control. The killing of intramacrophagic bacteria is mediated by a repertoire of molecular mechanisms unveiled by the host10. For example, macrophages launch oxygen-dependent killing of bacteria via NOX2 activation resulting in massive ROS production known to be toxic to S. aureus10,11. Here, we suggest that CAP generates cues that activate NOX2, and sets off a cascade of reactions that start with the endogenous production of superoxide, from which stem other noxious ROS with potent anti-staphylococcal activity. This hypothesis was tested in at least two different in vitro models of S. aureus infection with high experimental traceability. Using computer-aided transfer of human macrophages to reproduce the complexity of acute staphylococcal wound infection, we demonstrated that exogenous addition of two different NOX2 antagonists inhibits bacterial killing capacity of CAP in 3D skin model of infection. Furthermore, gene silencing and pharmacological inhibition of NOX2 in vitro significantly reduced endogenous ROS production and abrogated antibacterial effects of CAP in macrophages. Our previously published work showed that exogenous addition of ROS to infected macrophages enhanced their ability to kill S. aureus, whereas treatment of CAP-treated macrophages with antioxidants abrogated the antibacterial phenotype of CAP25. Our empirical data on detection of RONS available in CAP-treated medium demonstrated the presence of NO2 − and NO3−28 — small molecules capable of diffusing through several transport mechanisms including passive diffusion through the lipid bilayer of cytoplasmic membrane68. We also detected the presence of H2O2 in CAP-treated medium30. This chemical molecule is known to enter the cytosol through ion channels (e.g., H2O2-transporting channel aquaporin-3) thought to be an important regulator of H2O2 entry into the endosomal lumen69. Detection of water soluble RONS in CAP-treated medium suggests availability of bacterial oxidants with potent antimicrobial properties.

The action of CAP against bacterial pathogens in vivo is still an unanswered question. However, experiments performed in tractable 2D and 3D in vitro models of skin infection suggest that antibacterial action of CAP is ROS-dependent. We speculate that infected mouse wounds treated with CAP have significantly lower levels of viable bacteria due to: (1) transient delivery of higher levels of exogenous RONS to the wound site by CAP device, and (2) sustained delivery of lower levels of endogenous ROS that drive the respiratory burst of wound phagocytes. It is reasonable to hypothesize that RONS generated by CAP act as precursors for potent bacterial oxidants that (1) move across the plasma membrane of infected phagocytes, (2) enter the cytosol, (3) cross the membrane of bacteria-bound intracellular vacuole, and (4) mediate bacterial killing inside the phagolysosomal lumen. This hypothesis is strengthened by our data, which demonstrates that addition of ROS scavenger (NAC) or antioxidant enzyme (catalase) inhibits bacterial killing in CAP-treated macrophages25. Apart from exogenous delivery of ROS, endogenous host-derived oxygen-dependent bacterial killing may also explain the anti-staphylococcal action of CAP in vitro and in vivo. We provide evidence that oxygen-dependent bacterial killing in macrophages is triggered via NOX2 in vitro. We next studied the state of activation of this critical antibacterial host defence mechanism. Phosphorylated p40phox and p47phox are positive regulators of NOX29,10. Importantly, our confocal microscopy and immunoblotting experiments indicated that in addition to being activated by phosphorylation, both p40phox and p47phox, were expressed in significantly higher levels on the phagolysosomal membrane of CAP-treated macrophages compared to control. This implies that CAP activates NOX2 by facilitating the assembly of cytoplasmic components (phosphorylated p40phox and p47phox) of superoxide-yielding enzyme at the membrane of phagocytic vacuole. Macrophages kill intracellular S. aureus in membrane-bound vacuoles enriched with LAMP-1+ 12. We demonstrated that decoration with LAMP-1 (late phagosomal marker) and NOX2 and, more importantly, their localization at the phagolysosomal membrane of infected macrophages was significantly increased in response to CAP treatment compared to control. The functional significance of this observation is twofold. First, CAP promotes LAMP-1 acquisition necessary for vacuole maturation and bacterial killing within acidic organelles, which prevents the formation of bacterial reservoirs that account for bacterial persistence in the host and recurrence of staphylococcal disease. Second, higher levels of membrane-bound NOX2 warrant exuberant phagocyte NADPH oxidase activation and efficient release of bactericidal superoxide. According to previously discovered mechanisms, there exists a link between the formation of superoxide (oxidative killing of bacteria) and activation of proteases (non-oxidative killing of bacteria) in phagocytic vacuole70. Interestingly, our recently published study showed that increased levels of intraphagolysosomal proteolytic cathepsin D, known to degrade bacteria, were associated with CAP compared to control25. Taken together, we suspect that apart from direct activation of oxidative killing of bacteria via phagocyte NADPH oxidase activity, CAP may also stimulate the formation of molecular signals in the form of oxygen derivatives that result in indirect electrogenic70 regulation of proteases that perform non-oxidative killing of bacteria. Another molecule that plays a role in activation of oxidative killing of bacteria via NOX2 mechanism is Rac—a member of the Ras superfamily of GTP-binding proteins9,13,71. The GTP-bound form of Rac was consistently upregulated after CAP treatment indicating that CAP primes NOX2 by inducing active Rac-GTP. Together, our results highlight the capacity of CAP to facilitate oxidative killing of bacteria via NOX2 mechanism, which initiates superoxide production and increases over time by triggering, yet to be discovered, upstream effector mechanisms (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Additional insights may come from comparison of loss-of-function models and gain-of-function tests that may unveil additional mechanisms triggered by CAP and further explore its potentially multimodal action in vivo. We strongly believe that to verify the results obtained in our in vivo study, the next step is to use species with the skin architecture similar to that of the humans. In our experience, a porcine model is an efficient research tool for studying infected burn wound healing, because it overcomes certain technical limitations associated with mouse models, including inability to harvest partial-thickness skin grafts and expand them through perforation. Furthermore, certain bacterial virulence factors involved in human staphylococcal infections have less involvement in mouse models2,72, making preclinical models of wound healing that accurately mimic human skin morphology particularly relevant.

Our results indicate that, at a functional level, anti-staphylococcal effect of CAP is NOX2-dependent in both mouse and human in vitro models of wound infection. These observations indicate that the activation of NOX2 is not necessarily a specialized response restricted only to mice but may also apply to human infections. Previous studies established that CAP has broad spectrum antibacterial efficacy24, justifying its use in polymicrobial wound infections. Further in vivo experiments will be required to fully elucidate these hypotheses. Another important experiment will need to be devised to determine whether CAP has a potential to activate phagocyte NADPH oxidase signaling in vivo. Recent developments in spatial and single-cell proteomics designed to detect subtle biochemical modifications that occur to one or more amino acids73, may possibly allow the in vivo detection of protein modification that can result in a different outcome due to alterations in the signaling mechanism.

Although this study focused on the effect of CAP on macrophage responses, we believe that evaluation of its influence on neutrophils is equally as important. We will make these evaluations in our future work.

In summary, we reveal that treatment of infected mouse wounds with CAP (1) increases the length of neoepidermis, (2) stimulates collagen I synthesis and (3) significantly reduces bacterial wound burden. Additionally, we elucidate a so far unknown mechanism of action of CAP, which drives its antibacterial effect by inducing superoxide-generating NOX2 activation via Rac-GTP. The consequence of long-term exposure of S. aureus to CAP remains to be investigated. It may be debated that repeated treatment with CAP may activate the transcription of bacterial genes encoding for staphylococcal antioxidant defence and induce selective pressure for the resistance phenotype. Finally, if one recognizes the limitations of CAP and is realistic about where, when and to what extent it may be used, this technology may be beneficial in conjunction with antimicrobial arsenal currently available to the clinician.

Methods

Study design

The overall objective of this study was to determine the efficacy and mechanism of action of CAP in the context of bacterial wound infection. Experimental approaches comprised in vivo studies in mice, in vitro analyses in human bioengineered 3D models of staphylococcal wound infection, and in vitro studies in 2D models of infection using mBMDM and RAW264.7 macrophages.

The efficacy of CAP was investigated using a murine model of infected full-thickness burn wound reconstructed with allogeneic skin graft. To monitor bacterial burden, wounds were infected with a bioluminescent strain of S. aureus. Two series of in vivo experiments were performed each consisting of three groups, namely, (1) sham or S. aureus-infected mice treated with placebo gas (2) S. aureus-infected mice treated with CAP, and (3) positive control or S. aureus-infected mice treated with anti-staphylococcal antibiotic. Each treatment was administered locally 6 h after infection, and once daily thereafter. Real-time monitoring of wound infection in living animals was performed once every 48 h over 14 days via bioluminescence imaging. Bioluminescent measurements were correlated with bacterial enumeration by calculating the number of living bacteria in a homogenized sample of wound biopsy. The experiments were arbitrarily ended after 3-, 7- and 14-days post-infection to recapitulate the main phases of wound healing: inflammatory, proliferative and remodeling. Longitudinal assessment of microscopic wound size, length of neoepidermis and new extracellular matrix formation was based on histological wound staining, quantitative RT-qPCR, chromogenic detection of protein expression, confocal and two-photon microscopy techniques.

Following acclimation period of 7 days prior to use in surgery, age-matched animals were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups. Prior power calculations were performed to predetermine the sample size using an open-access software (https://shade.pasteur.fr/) and based on previous experience with similar wound healing models. Placebo controls were used, and no bias was applied during husbandry or during tissue harvesting. Blinded assessment of experimental outcomes was not always applicable; however, it was used whenever possible. Animals that did not reach experimental end point of a study due to failure to recover from general anesthesia were removed from the study. Animals that reached a predefined humane end-point were excluded from the study. Histological samples were randomized using a computer-based random number generator. Histological slide assessment and data acquisition were performed by two assessors. Only one of the two assessors was formally blinded. For representative images, at least six fields of view were examined microscopically in at least five biological replicates; the numbers of biological replicates for each experiment are in the figure legends. Sources of variability and conditions that could potentially bias results were controlled where possible. All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon. All mice that received placebo control, topical antibiotic or cold atmospheric plasma were treated by the same operator. All animal studies were approved by relevant Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were maintained and humanely euthanized by overdose of inhalant anesthetic followed by cervical dislocation at predefined study end points. All procedures were in accordance with the European and French Code of Practice for the Care and the Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes.

To identify the mechanism of action, we hypothesized that antibacterial efficacy of CAP is NOX2-dependent, and therefore, signaling pathway activation and inhibition studies were performed in 3D and 2D in vitro models of wound infection using pharmacological inhibitors and genetic ablation. To delineate underlying mechanisms, a range of cellular and molecular biology techniques were performed to evaluate cellular proliferation, intracellular ROS production, gene expression, post-transcriptional modification of proteins and assembly of phagocyte NADPH oxidase components at phagolysosomal membrane of infected macrophages. Bioengineered wounds were fabricated using automated 3D printing technology with high precision and reproducibility. Inhibition studies using 3D bioengineered human wound equivalents further strengthened the argument that the antibacterial action of CAP is NOX2 dependent. Multi-cellular 3D wounds consisted of human primary keratinocytes, fibroblasts and peripheral blood monocytes collected from the same human donor. Human tissue samples were obtained from patients undergoing elective surgery after written informed consent and approval by relevant human ethics committees of “Le Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation” (number AC-2018-3243 and DC-2018-3242). The number of experimental replicates is indicated in the figure legends.

In vivo mouse model

All experiments were approved by the Institut Pasteur Animal Ethics Committee (approval number APAFIS#15346-2018053111431668 v1) following European and French Code of Practice for the Care and the Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes (Council Directive 86/609/EEC). Six-weeks-old (20–25 g), inbred, immunocompetent hairless female Crl:SKH1-Hrhr mice (Charles River Laboratories, Germany) were randomly assigned to one of three groups of six to twelve animals per group as predetermined by statistical power calculations. Two series of experiments were performed each involving 45 mice. The total number of 90 mice were used in the study. Not all mice reached the final time-point. Intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 µg/g) and xylazine (10 µg/g) was administered to induce general anesthesia, and subcutaneous injection of lidocaine (5 µg/g) was administered to induce local anesthesia. Buprenorphine (0.05 µg/g) was administered subcutaneously, and paracetamol (3 mg/ml) was added to drinking water to control intra and post-operative pain. A 79-mm2 burn wound was created on the dorsal surface using a brass block as previously described28. Twenty-four hours after the wound induction, necrotic tissue was excised to fascia and reconstructed with a full-thickness allogenic skin graft originating from the donor’s tail and secured with a Leukosan surgical adhesive (BSN medical, Hamburg, Germany). S. aureus Xen36 overnight cultures were diluted in BHI and bacteria were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1. Bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 3500 × g for 15 min and washed three times in PBS. Following skin grafting, mouse wounds were infected topically with 1 × 108 bacteria diluted in 50 µl of PBS. Serial dilutions of the inoculum were plated to control the number of bacteria inoculated. Wounds were treated once daily (in the morning) with either (1) placebo control (topical treatment with inert, helium gas), (2) topical treatment with CAP (2 min, 24 kV) or (3) topical application of 200 µl of mupirocin at 2% w/v (Bactroban, GlaxoSmithKline, Middlesex, UK). Low-adherent paraffin gauze (Adaptic, North Yorkshire, UK) wound dressing and Micropore™ Surgical Tape (3 M, Cergy-Pontoise, France) were changed daily. CAP treatment and wound dressings were performed under anesthesia, which was induced by inhalation of isoflurane (4% induction at 2 L/min and 2% maintenance at 500 ml/min).

BLI was performed on alternate days to assess bacterial wound burden in living animals. Bacterial wound burden was assessed by measuring bioluminescent signal in anesthetised animals using IVIS Spectrum Imaging system and Living Image 4.5.5 software (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA, USA). Two wound biopsies were collected at 3, 7 and 14 d. p. i. using a sterile 6 mm biopsy punch (Acuderm Inc. FL, USA). The first wound biopsy was homogenized, serially diluted on BHI plates and grown over 24 h at 37 °C. Colonies were counted to assess bacterial load per biopsy. The second wound biopsy was bisected with one half fixed in 10% buffered formalin and processed for histology and immunohistochemistry. The other half was fast frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction, MPO and NAG quantitation.

Cold atmospheric plasma

Biocompatible helium gas was used to produce plasma as previously described28,30. The plasma source consisted of a dielectric polylactic acid capillary surrounded by a high-voltage electrode, through which flows helium gas. CAP was propagated from the source to the target in a single channel plasma jet (Supplementary Movie 1). Voltage was set to 24 kV during in vivo and 32 kV during in vitro experiments corresponding to an operating power of 50 ± 10 mW and 90 ± 10 mW respectively. Helium mass flow was regulated by mass flow controller and set to 500 standard cubic centimetres per minute (sccm). The gap between CAP nozzle and the target was set to 4–6 mm. The duration of treatment in all experiments was 2 min. In the in vivo experiments, mouse skin temperature was monitored after CAP treatment with an infrared thermal imaging camera (Testo Ltd, Alton, Hampshire, UK). CAP had no effect on mouse skin temperature. The optical emission spectra of ultra violet radiation produced by the CAP device was not measured in this study. The concentration of chemical species (H2O2, NO2− and NO3−) in plasma-activated medium was indicated in our previous work30.

Biofabrication of three-dimensional human skin

Primary human keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts were isolated from male and female adult skin through enzymatic dissociation. The skin specimens were sampled by a surgeon during sessions of elective abdominoplasty or reduction mammoplasty. The study was conducted in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all donors. All protocols were performed in accordance with national laws and guidelines for the collection, use and storage of human tissue. Keratinocytes were cultured in EpiLife medium (Gibco Paisley, PA, USA) supplemented with Human Keratinocytes Growth Supplement (Gibco Paisley, PA, USA). Fibroblasts were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 Medium (Gibco Paisley, PA, USA) supplemented with 15% FetalClone III (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden). All cells were used at passages 2–3. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from buffy coat using Ficoll (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden). CD14+ monocytes were isolated by magnetic selection (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergish Gladbach, Germany) and differentiated using M1-Macrophage Generation medium DXF (PromoCell GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). Three-dimensional modeling computer software, including open-source 3D printing toolbox (Slic3r https://slic3r.org/) and SketchUp (Trimble Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA), were used to design the pattern of 3D structures. Computer-aided transfer of prescribed organization was performed through deposition of bioink formulation (CTI BIOTECH, Lyon, France) containing single-cell suspensions. Three-dimensional skin models were built through the layering of printed filaments with the assistance of a BIO XTM bioprinter (CELLINK, Gothenburg, Sweden). Following bioprinting, skin models were cultured for 21 days. During this period, 3D models were cultured in medium (CTI Biotech, Lyon, France), which aided dermal maturation, epidermis differentiation, and air-liquid interphase cornification. Each sample measured 1 cm (length) × 1 cm (width) × 200 µm (depth). Cellular viability was controlled at day 21 after bioprinting with an alamarBlue™ Cell Viability Reagent (Life Technologies Corporation, Eugene, OR, USA) and Invitrogen™ LIVE/DEAD™ Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit for mammalian cells (Life Technologies Corporation, Eugene, OR, USA).

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

The bioluminescent Staphylococcus aureus Xen36 strain (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) was used in this study. This MSSA strain was derived from a clinical isolate of bacteremic patient and has been genetically engineered to express a stable copy of the modified Photorhabdus luminescens luxABCDE operon at a single integration site on a native plasmid. A highly virulent MRSA strain, Staphylococcus aureus USA300, was obtained from ATCC (reference BAA-1717). Bacteria were grown aerobically, as previously described25, in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with shaking at 200 rpm at 37 °C or on BHI agar plates. Overnight cultures were collected or diluted 1:50 in fresh BHI and grown at 37 °C until exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0). OD600 values were measured using a Biochrom Libra S22 spectrophotometer (Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, UK).

Histology, immunohistochemistry and image analysis

Histological sections (4 μm thickness) were prepared from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue, which were stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) or subjected to immunohistochemistry using a Leica Bond III stainer (Leica Biosystems, Nanterre, France). Primary antibodies were applied and incubated for 1 h. Detection was performed by species-specific horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Sections were reacted with one of two substrates: (1) for HRP, 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) with Bond enhancer (AR9432, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), which produced a brown to black color or (2) for AP, Bond Polymer Refine Red (DS9390, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), which yielded a bright red color. For identification of non-specific binding and other experimental artefacts, negative controls were used. These consisted of omission of primary antibodies with a non-immune immunoglobulin of the same isotype and concentration as the primary antibody or incubation with antibody diluent. All control sections showed negligible staining. The list of antibodies and dilution factors is provided in Table 1. Stained sections were scanned using a Lamina instrument (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA), visualized with the CaseViewer digital microscope application (3Dhistech, Budapest, Hungary), and analyzed with ImageJ software.

Histological wound assessment

Histological slides stained with H&E were evaluated for the microscopic wound length. The public domain software ImageJ was used to determine the microscopic wound length by drawing a straight line between the dermal wound margins. To estimate the length of neoepidermis, the area of the wound that was covered with newly formed epidermis was measured and expressed in µm.

Quantification of immunohistochemical staining was by color deconvolution as described previously74,75. A total of six microscopic fields of view were used for the immunohistochemical data analysis. Out of the six microscopic images, two represented the region around the left border of the wound lesion, two additional images included the graft region, and the two remaining images included the area around the right border of the wound. Both the epidermal and dermal regions were assessed. Control average was normalized to 1. For each time point, the value of integrated density (arbitrary units) is shown relative to the value of the integrated density in control.

Gram staining

Sections (4 µm) of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue were de-waxed and taken through a decreasing series of graded alcohols to water. Gram staining was performed using a Gram Stain Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) to visualize S. aureus in tissue sections according to the manufacturer’s instructions. S. aureus are stained in blue and the remaining biological tissue is visible in varying shades of magenta.

Masson’s trichrome and May Grunwald-Giemsa staining

For histological assessment of collagen deposition in the dermis, trichrome staining was performed using a Masson Trichrome Staining Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). May Grunwald-Giemsa staining was performed on formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections to visualize cellular components of human bioengineered skin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA).

Multiphoton microscopy

TriM Scope™ Matrix multiphoton microscope (LaVision BioTec GmbH Miltenyi Biotec Company, Bielefeld, Germany) equipped with a 25 × water immersion objective with numerical aperture of 0.95 (XLPLN25XWMP2; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to assess cellular viability in live bioengineered skin. Following bioprinting and in vitro maturation (i.e., 21 days after 3D bioprinting), bioengineered skin samples were incubated (1 h, 37 °C) with reagents provided in Invitrogen™ LIVE/DEAD™ Viability/Cytotoxicity kit. Bioengineered skin was scanned in 1024 × 1024 pixel/frames, which represents a scanned area of 393 µm × 393 µm. The InSight® X3+™ laser (Spectra-Physics®, Milpitas, CA, USA) was tuned at 910 nm to capture calcein-positive cells (pseudocolored green) and 1100 nm for ethidium homodimer-1-positive cells (pseudocolored red). Signals were collected using non-descanned GaAsP detectors (Hamamatsu Corporation, Hamamatsu City Japan). Sequentially, live cells were detected through a bandwidth filter 500 nm to 520 nm and dead cell signal was detected through a bandwidth filter 568 to 593 nm of two non-descanned detector in a backscattering geometry. Maximum intensity projection images were generated using Fiji > Image > Stack > Zproject tools.

Collagen second harmonic generation

Multiphoton inverted stand Leica SP5 microscope (Leica Microsystems Gmbh, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to assess mouse wounds ex vivo as previously described30. A Ti:Sapphire Chameleon Ultra (Coherent, Saclay, France) with a center wavelength at 810 nm was used as the laser source to generate second harmonic and two-photon excited fluorescence signals (TPEF). The laser beam was circularly polarized and equipped with a Leica Microsystems HCX IRAPO 4x/0.95 W objective, which was used to collect and excite second harmonic generation (SHG) and TPEF. Signals were detected in epi-collection through a 405/15-nm and a 525/50 bandpass filters respectively, by NDD PMT detectors (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). LAS software (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) was used for laser scanning control and image acquisition. SHG signal (magenta) is emitted from collagen I fibers and TPEF (green) is due to the signal emitted by cellular and tissue constituents of the skin. Combined SHG and TPEF backscattering microscopy technique provides complementary information and allows non-invasive, spatial characterization of skin tissue and wounds.

SHG and TPEF images were acquired using detectors with a constant voltage supply and constant laser excitation power allowing direct comparison of SHG intensity values. Analyses were performed using homemade Image J routine (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Two fixed thresholds were chosen to distinguish biological material from the background signal (TPEF images) and specific collagen fibers were imaged with SHG images. Collagen SHG score was then established by comparing the area occupied by the collagen relative to the sample surface. TPEF (green) and SHG (magenta) images were pseudocolored and overlaid for publication using Image J. Several microscopic fields of view were captured with a 4 × objective lens. A montage scan of the entire section was reconstructed and wound edges determined on either side of the graft. The SHG signal was quantified over the area between the left and right borders of the wound, which included the region covered by the skin graft.

TUNEL assay and DNase I treatment

The Calbiochem® TdT-FragEL™ DNA Fragmentation Detection Kit was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France). Formalin-embedded samples of mouse skin tissue were sectioned (4 µm) and placed on a glass slide pre-coated with Biobond tissue section adhesive (vWR International, Radnor, PA, USA). Skin tissue sections were treated according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, all sections were deparaffinised by immersion in HistoClear (Euromedex, Souffelweyersheim, France) and hydrated by transferring the slides through a graduated ethanol series to 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS) solution. Specimens were stripped of proteins by incubation with 100 µl of 20 µg/ml proteinase K per section. A positive control was generated by using deparaffinised sections of mouse skin that were initially incubated with 20 µg/ml proteinase K, and then treated with 1 µg/µl DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France) in 1 × TBS/1 mM MgSO4. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) binds to exposed 3′-OH ends of DNA fragments generated in response to apoptotic signals and catalyses the addition of fluorescein-labeled and unlabeled deoxynucleotides. When excited, fluorescein generates an intense signal at the site of DNA fragmentation of apoptotic cells. DAPI staining was used to visualize normal and apoptotic cells. TUNEL-stained sections were scanned using a Lamina instrument (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA), and analyzed with the CaseViewer digital microscope application (3DHISTECH).

Infection of bioengineered three-dimensional human skin

At day 21 after bioprinting, 3D bioengineered skin was inoculated by injecting a total of 1 × 108 of S. aureus Xen36 bacteria diluted in 50 µl of PBS. To maximize the even distribution, the intradermal inoculum was administered through five entry points (10 µl at 12, 3, 6 and 9 o’clock plus one in the center). Serial dilutions of the inoculum were plated to control the number of bacteria inoculated. Culture medium was not supplemented with antibiotics. Each model was treated for the duration of 2 min with either placebo control (helium) or CAP at 1 and 4 h. p. i. All skin models were collected at 24 h. p. i. and homogenized in 2 ml of 1 x PBS. Homogenized skin was serially diluted, plated onto BHI plates and grown overnight at 37°C. CFU were enumerated to assess bacterial load. CFU average in control group was normalized to 1.

Cells and culture conditions

Murine macrophage-like cell line RAW 264.7 (ATCC®, Molsheim, France) was grown in DMEM high glucose supplement pyruvate (Gibco Paisley, PA, USA) and 10% fetal calf serum (BioWest, Nuaillé, France) at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Primary macrophages were obtained from flushed bone marrow originating from femurs and tibias of female C57BL/6J. Mouse BMDM were cultured for 7 days in complete medium containing RPMI 1640 Medium (Gibco Paisley, PA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (BioWest, Nuaillé, France), 2 mM glutamine (Gibco Paisley, PA, USA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco Paisley, PA, USA), 10 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 U ml−1 penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco Paisley, PA, USA) and 25 ng/ml mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

Primary dermal fibroblasts were isolated from patients undergoing mammoplasty and/or abdominoplasty as previously described30. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients and the study protocol is conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Dermis and epidermis were separated and dermis was dissociated in an enzymatic bath containing dispase II (2.4 UI/ml) and collagenase II (2.4 mg/ml) (Gibco, Paisley, PA, USA) during 2 h under agitation at 37 °C. After filtration, the suspension was centrifuged at 450G during 5 min and the fibroblasts were counted and seeded at 20,000 cell/cm2 in the growing medium made of DMEM Glutamax, supplemented with 1% antibiotic (Gibco, Paisley, PA, USA) and 10% HyClone FetalClone II serum (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA, USA).

Scratch wounds in human dermal fibroblasts

To examine the direct effect of CAP on collagen synthesis, primary human dermal fibroblasts were suspended in 500 μL of in DMEM Glutamax, supplemented with 1% antibiotic (Gibco, Paisley, PA, USA) and 10% HyClone FetalClone II serum (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA, USA). Fibroblasts were seeded into a 24-well plate at 3 × 105 cells/ml. Confluent monolayers of fibroblasts were scratched with a P200 pipette tip producing a wound of approximately 2 mm × 1 cm. Scratch wounded fibroblasts were rinsed once with complete medium to remove detached cells. Unwounded and scratch-wounded fibroblasts were treated either with helium (2 min, distance = 1 cm) or CAP (2 min, distance = 1 cm). Helium and CAP-treated fibroblasts were harvested at 6 and 24 h post-CAP treatment and processed for RNA extraction. All experiments were based on fibroblasts isolated from the skin originating from four different donors. Three independent experiments with at least three biological replicates were used to represent the data.

Bacterial infection of macrophages

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded onto a 24-well plate at a density of 105 cells per well. Cells were infected with S. aureus (MOI of 10), and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. The samples were incubated for another 30 min, but this time with gentamicin-containing medium at 20 µg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) to kill extracellular bacteria. After a washing step, 1 ml of complete medium was added and macrophages were treated either with placebo control (inert helium gas) or CAP for 2 min (distance 4–6 mm). Infected cells were lysed at 0, 2 and 5 h post infection with 0.1% Triton X-100. For enumeration of intracellular bacteria, dilution series of lysed macrophages were plated onto BHI agar.

Primary BMDMs were plated at 5 × 105 cells/ml onto a 92 × 16 mm Petri dish and cultured in the presence of complete medium. At day 5, medium was replaced with fresh complete medium. At day 7, cells were washed and seeded onto a 24-well plate at a density of 105 cells per well. Cells were cultured in complete medium without antibiotics and incubated for 24 h before bacterial challenge. For infection of BMDMs, bacteria were grown in BHI overnight, then regrown to exponential phase and added to the cells at a MOI of 10, centrifuged at 900 × g for 1 min and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. To follow a synchronized population of bacteria, extracellular bacteria were killed through incubation of BMDM in RPMI containing 20 μg/mL gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for 30 min. To compare the intracellular growth profiles of control and CAP-treated macrophages, the samples were then either lysed immediately, to measure the initial number of intracellular bacteria, or replaced with fresh media containing gentamicin (20 µg/mL), thus permitting intracellular bacteria to replicate for 2 or 5 h. p. i. For enumeration of intracellular bacteria, infected cells were lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min and dilution series were plated onto BHI agar. The number of living intracellular bacteria was monitored by counting CFU. The initial number of intracellular bacteria (0 h. p. i.) was averaged was normalized to 100. The data reported are the means and standard error of means of triplicate determinations and are representative of at least three experiments.

Cell proliferation assay

Cellular proliferation was determined using tetrazolium salt WST-1 reagent (Roche Applied Science, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), which is cleaved to soluble formazan by cellular mitochondrial dehydrogenases. Infected RAW 264.7 and BMDM were treated with either placebo control or CAP and supernatants were collected from cultured macrophages at 0, 2 and 5 h. p. i. Colorimetric assay (WST-1 based) for the quantification of cell proliferation was performed using the 96-well-plate format according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (GloMax® Discover Microplate reader, Promega, MI, USA) at 555 nm.

ROS measurement

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at a density of 105 cells per well. Cells were infected with S. aureus at a MOI of 10, gently centrifuged and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C to synchronize phagocytosis. The extracellular bacteria were eliminated by the addition 20 µg/mL gentamicin-containing medium and incubation for 30 min. Cells were treated by placebo control (helium) or CAP for 2 min. Fluorometric intracellular ROS probe (Catalog Number MAK142, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was added and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Fluorescence was measured using a microplate reader (GloMax® Discover Microplate reader, Promega, MI, USA) at 640 nm.

Pharmacological inhibition of NOX2

RAW 264.7 cells and bioengineered human skin were pre-incubated with two different NOX2 inhibitors: (1) GSK2795039 (MedChemExpress, NJ, USA) at 30 and 50 µM respectively, and (2) gp91 ds-tat (Anaspec, CA, USA) at 50 and 100 µM respectively. Following a 30-min incubation with GSK2795039 and gp91 ds-tat, samples were treated either with placebo control (helium) or CAP.

Transfection of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with non-targeting negative control siRNA (ON-TARGETplus Non-Targeting Control Pool, Dharmacon, CO, USA) or endogenous positive control siRNA (ON-TARGETplus GAPD Control Pool, Dharmacon, CO, USA) at final concentration of 25 nM. ON-TARGETplus Mouse Cybb siRNA (Dharmacon, CO, USA) was transfected at 50 nM final concentration using DharmaFECT™ transfection Reagent (Dharmacon, CO, USA). Transfection of negative control, positive control and target siRNA was performed in serum-free medium in triplicates according to manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA extraction and cell viability analysis were performed at 24 h after transfection. Samples with target mRNA knockdown of >80% and cell viability >80% were used for subsequent experimentation. siRNA-mediated silencing of Cybb was monitored and assessed using a ΔΔCq method to determine relative gene expression from qPCR data with an endogenous reference gene and non-targeting siRNA (ON-TARGET plus Non-Targeting Control Pool, Dharmacon, CO, USA). RAW 264.7 cells exhibited siRNA knockdown of Cybb message with mRNA reduction of ≥80% when cells were treated with 50 nM final concentration of the targeting Cybb siRNA.

RNA isolation

RNA isolation from RAW 264.7 cells and primary human fibroblasts was carried out using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and RNeasy Mini Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) as described by the manufacturer. Total RNA was isolated from mouse wounds, which were homogenized in TRIzolTM Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using GentleMACS M-tubes (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and gentle MACSTM dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After homogenizing the sample with TRIzol™ Reagent, chloroform was added. RNA was precipitated with isopropanol, washed to remove impurities, and then resuspended for use in downstream applications. DNA elimination was performed using Invitrogen™Ambion™TURBO DNA-free kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies Corporation, Oregon, USA). Total RNA concentration was quantified using Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) or Qubit® RNA BR Assay Kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies Corporation, Oregon, USA). The RNA quality was determined by analyzing the proportion between 28S to 18S ribosomal RNA electropherogram peak using an Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Samples with an RNA integrity number >8 were used for cDNA synthesis.

Quantitative reverse-transcription–PCR

cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using reverse Transcriptase Core Kit (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). Quantitative reverse-transcription–PCR (qRT–PCR) was performed using a QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and C1000 CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA). Gene expression assays were performed with primer sequences purchased from Qiagen (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). The list of primers is provided in Table 2. In experiments involving primary human fibroblasts, qRT-PCR was performed as follows. A final volume of 10 μl was prepared, which consisted of 1 μl of cDNA (10 ng/μL), 1 μl of primer (10 mM) and 5 μl of SsoAdvancedTM Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA) and ultrapure water. The C1000 CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA) was programmed using the following parameters: 3 min at 95 °C and 40 cycles of three steps (30 s at 98 °C; 15 s at 98 °C and 30 s at 60 °C).

In all experiments at least three reference genes were tested to establish the stability value. Two housekeeping genes with the highest stability value were used to normalize cDNA within each sample. Differences were calculated using the Ct and comparative Ct methods for relative quantification. The relative level of gene expression was normalized with a housekeeping gene and used as a reference to calculate the relative level of gene expression according to the following formula: 2−ΔΔCt, where −ΔΔCt = Δ Ct gene − Δ Ct Average where Δ Ct gene = Ct gene − Ct (housekeeping gene) and Δ Ct Average = Average Δ Ct control. For all biological replicates, two technical replicates were performed. All samples were evaluated in at least three independent experiments.

Fluorescence microscopy