Inflammation: a matter of immune cell life and death

Part 1. The life cycle of inflammation

The wound-healing response

Much of mammalian injury and disease can be understood through the lens of inflammation and wound healing. The wound healing response to injury in humans is well known with respect to the cells and molecules involved, the time course for specific events, and the negative consequences when such components are blocked. Healthy wound healing is broken into four phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. In this section, we will focus on inflammation. A detailed description of the other phases can be found in previously published reviews1,2. Critical cellular orchestrators of inflammation are cells of the innate immune system, such as neutrophils and macrophages. Following injury, in an effort to reestablish homeostasis, neutrophils are recruited to sites of injury following platelet degranulation of cytokines and growth factors. This recruitment is aided by mast cells, which, in addition to releasing antimicrobial peptides, release molecules to break down the extracellular matrix and increase the permeability of blood vessels1. Neutrophils help to decontaminate the wound by phagocytosis of bacteria and foreign bodies and secretion of high levels of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules to accelerate further immune cell recruitment and activation3. Recruited monocytes and tissue-resident macrophages contribute to the cytokine-rich inflammatory environment and support the majority of debris clearance via phagocytosis4. Signaling molecules and antigen presentation by these cells, as well as dendritic cells, are also critical for mounting an adaptive immune response to pathogens5,6. Neutrophils then undergo apoptosis and are cleared within approximately one day of their arrival7. Efferocytosis, or apoptotic cell clearance, is a tightly regulated physiologic process, as demonstrated by more than 109 apoptotic cells cleared daily in the absence of injury or disease by the immune system without an inflammatory immune response5. When neutrophils are efferocytosed by macrophages following injury, the macrophages direct a transition from inflammation towards repair and regeneration8. This phenotypic transition is necessary for the resolution of inflammation to maintain or restore tissue function9,10.

While macrophage infiltration and pro-inflammatory activation is crucial for tissue repair and homeostasis maintenance11, subsequent macrophage polarization towards an anti-inflammatory, pro-regenerative phenotype is similarly required to enable complete wound repair12,13,14,15. Macrophage response to apoptotic cell engulfment is mediated by several receptors on the macrophage that can bind to a variety of apoptotic surface markers to facilitate recognition, uptake, and signaling. Exposure of the phospholipid phosphatidylserine (PS) onto the outer surface of the cell membrane is the most well-characterized apoptotic cell signal16,17. In most living cells, PS is confined to the inside of the cell by a flippase, a lipid transporter protein that moves certain lipids from the outer leaflet to the inner leaflet, producing anisotropic layers18. When that cell undergoes apoptosis, it loses its cell membrane anisotropy, exposing PS on its outer membrane. The exposure of PS acts as an “eat-me” signal to phagocytes, including macrophages, to engulf the dying cell18. This engulfment initiates a shift in macrophage polarization toward a pro-resolving phenotype, which reduces inflammation, stops additional damage to the tissue, and begins tissue regeneration19.

Normal healing vs chronic inflammation

Macrophages display significant plasticity to promote both inflammation and resolution based on extracellular signals20. In a healthy healing response, these cues can lead to the production of immunosuppressive cytokines, including TGF-β and IL-10 to restore homeostasis following an initial inflammatory phase; however, without a signal to polarize, or with continued stimulation by antigen, inflammation continues indefinitely in chronic inflammatory diseases21. In chronic or dysregulated inflammatory conditions, elevated numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages persist22,23,24. Neutrophils persist abnormally, releasing excessive proteases, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which damage tissue and sustain inflammation, while macrophages are skewed toward a pro-inflammatory (M1) state, failing to transition to a reparative (M2) phenotype. This imbalance perpetuates inflammation, delays healing in chronic conditions like non-healing diabetic wounds. Macrophage persistence at sites of inflammation can be associated with disease severity and progression, such as in rheumatoid arthritis25,26,27,28. Pro-inflammatory immune cells overproduce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), ROS, and inflammatory cytokines, leading to increased tissue damage. Additional pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization occurs with further upregulated secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-629. Similar outcomes from increased macrophage infiltration and activation can be seen across a variety of inflammatory diseases and organ systems29,30,31,32. In contrast, normal healing is associated with the programmed death and clearance of neutrophils, which initiates an anti-inflammatory cascade in the tissue33.

Part 2. Cell death

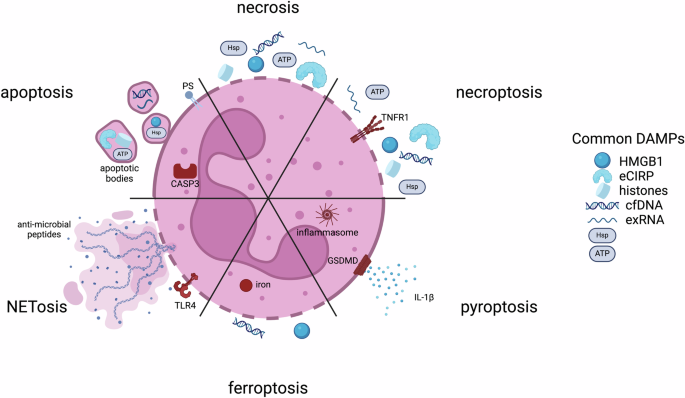

The precise timing, mode, and extent of neutrophil death and removal from the wound environment dictates subsequent inflammation and healing34. Both the initial inflammatory phase and the subsequent anti-inflammatory, pro-regenerative phase are necessary for full wound healing. Here we describe various modes of neutrophil death and the resulting effects on inflammation, focusing on the impact on macrophages35 (Fig. 1).

(PS phosphatidylserine; CASP3 caspase-3; TLR4 toll-like receptor 4; TNFR1 tumor necrosis factor receptor 1; GSDMD Gasdermin D; HMGB1 high mobility group box 1; eCIRP extracellular cold-inducible RNA-binding protein; cfDNA cell-free DNA; exRNA extracellular RNAs; Hsp heat shock protein)

Necrosis and apoptosis

To maintain normal homeostasis, the short half-lives of neutrophils ordinarily require a well-regulated program of apoptosis initiated through either intrinsic or extrinsic pathways. The intrinsic cascade begins through cytochrome C release from the mitochondrial to the cytoplasmic space, leading to the activation of caspase-3. In contrast, the extrinsic cascade begins with the engagement of cell death receptors on surfaces, subsequent activation of caspase-8/caspase-10 and convergence on caspase-336. While nitric oxide is important in the wound healing response as an inflammatory mediator, it also plays a role in neutrophil apoptosis. Both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways involve the upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and the production of nitric oxide which activate caspases-3 and -8, resulting in cell death37. The mechanism of apoptosis leads to a series of active events that modulation inflammation downstream. In addition to the exposure of PS on apoptotic cell surfaces, a host of “eat me” signaling molecules are expressed on cell surfaces along with a downregulation of “don’t eat me” signals, e.g. CD47, leading to efferocytosis and clearance by phagocytes38.

Neutrophils are the most numerous immune cells in the human body with over 1 billion produced per day per kilogram. This, coupled with a lifespan of a few days at most, means that a majority of these cells are undergoing apoptosis daily, primarily in the bone marrow, liver, and spleen. The result of these processes are a production of interleukin-23 (IL-23), a reduction in granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) levels, and a reduction in neutrophil production39. This process then forms a self-regulatory loop of neutrophil production, mobilization, and decline. Apoptosis is therefore considered a non-inflammatory mode of cell death in contrast with other neutrophil death mechanisms.

There are modes of apoptosis, however, that are immunogenic and result in the active release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs, Fig. 1). DAMPs released from dead and dying cells serve to signal downstream inflammatory mediators, including macrophages to recruit to sites of injury and enhance the inflammatory cascade40,41. Canonical DAMPs include ATP, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), extracellular cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (eCIRP), histones, heat shock proteins (HSPs), extracellular RNAs (exRNAs), and cell-free DNA (cfDNA). DAMPs are also released passively via cell necrosis, that is exemplified by loss of cell membrane integrity. The packaging and identity of DAMPs released from programmed death mechanisms versus necrosis differ. Apoptosing neutrophils can secrete DAMPs via lysosomes, via release exosomal and ectosomal vesicles, apoptotic bodies, and via extracellular traps42.

As necrosis is generally a passive process, release of biologically active agents is via membrane lysis (Fig. 1). As such, differences in those molecules exist. For example, cfDNA release from necrotic cells is generally much longer than fragmented cfDNA released from apoptotic cells43. Other DAMPs, such as HMGB1, can be modified during certain modes of cell death, while following necrosis, it is not44. Certain DAMPs are released at different stages; in particular, ATP is released early during apoptosis, while HMGB1 is released later as cell move towards secondary necrosis, or during primary necrosis45. Membrane rupture can also be a cell-regulated process, termed necroptosis, that occurs following receptor-mediated interactions. This results in the uncontrolled release of cytosolic DAMPs (Fig. 1).

Other forms of programmed cell death

A number of other inflammatory modes of neutrophil death have been identified that are particularly important for neutrophils. Pyroptosis is a highly inflammatory mode of cell death that is triggered intracellularly via the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Fig. 1)46. Activation of caspases and involvement of Gasdermin D are hallmarks of this process resulting in DAMP release. Gasdermin D promotes pore formation in neutrophil membranes causing IL-1β to be released through the resulting pores along with other DAMPs. Ferroptosis is another cell death mode accompanied by loss of cell membrane integrity (Fig. 1)47. Intracellular iron accumulation increases oxidative stress in the cell, leading to an increase in lipid peroxidation and disruption of the lipid bilayer. Important DAMPs released through this process include HMGB1 and cfDNA. Finally, a purposefully inflammatory mechanism of cell death is that of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETosis, Fig. 1)48. NET production can be associated with both living or dying cells and involves the release of web-like, unraveled, chromatin structures containing DNA, histones, and anti-microbial peptides into the extracellular space. This process is triggered by microbial products and activated platelets, and the resulting structures are microbiocidal and highly inflammatory49,50.

Cell death in inflammatory disease

There is evidence in various disease pathologies that neutrophil death is perturbed and can lead to increased tissue damage. When apoptosis is restricted due to disease, the resulting neutrophil survival can lead to increased tissue damage. For example, in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis, persistent neutrophil activation is associated with high levels of inflammation in the lungs51. Excesses of inflammatory modes of cell death can similarly lead to exacerbation of disease conditions. The DNA and histone release following NETosis have the potential to trigger autoimmune responses52. Autoantibodies have been identified to target NETs in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. In severe cases of infection or injury, the DAMP release following widespread neutrophil necrosis can lead to the excessive inflammation that is present in sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and the COVID-associated cytokine storm53. Therapeutic strategies targeting neutrophil death have emerged either focusing on promoting the non-inflammatory apoptotic pathways or reducing the extent of pro-inflammatory generation of NETs and the release of DAMPs.

Stromal cell death as a model

Our own work examining stromal cell death has demonstrated that the mode of cell death matters with respect to downstream effects on immune cells54. We initiated stromal cell death through two protocols: 1) cycles of freezing and thawing and 2) heating. From each of these populations of dead cells, we isolated two fractions: 1) the cell pellet, which contained apoptotic bodies and cell debris, and 2) the cell supernatant, which contained soluble components such as DAMPs and cytokines. We tested these fractions for their effect on macrophage phenotype in vitro and on their ability to enhance muscle recovery in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia. Our hypothesis was that the release of DAMPs, including protein and nucleic acid content would be significantly greater in supernatants while the pellet fraction would be rich in PS-bound membrane components. We therefore hypothesized that the supernatant would be more inflammatory regardless of the mode of cell death.

We found that components from the freeze-and-thaw process (both the supernatant and the pellet) produced a clear anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative response on cultured bone marrow-derived macrophages. The soluble supernatant from the freeze-and-thaw process also remarkably improved the relative blood flow in the affected foot in our mouse model to the level of ∼80% of the intact foot when compared to the untreated, saline, and heat supernatant. Freeze-and-thaw supernatant–treated muscles produced a significantly greater average tetanic force than that of untreated muscles and heat supernatant–treated muscles. This indicates that the mode of cell death was more important in inflammation than the cell fraction. In a separate laboratory, soluble factors isolated from freeze-and-thaw killed cells were loaded into a hydrogel foam to use their immunomodulatory and angiogenic effects to improve chronic wound healing55.

Contributors to inflammation

As humans age, the accumulation of effects from repeated or low-grade infection, chronic inflammatory disease, obesity, and environmental factors leads to changes in the number and function of myeloid cells. This set of changes is one component of “inflammaging” – the accumulation of defects in the immune system associated with aging that lead to a persistent, low grade inflammatory state56. Neutrophils in particular show a reduced ability to phagocytose infectious bacteria and a reduced microbiocidal ability in aged individuals. The cells’ ability to conduct immune surveillance is impaired due to a decreased sensitivity to anti-apoptotic factors. Neutrophils in the elderly have a greater likelihood to undergo apoptosis without triggering inflammation. Advanced age can therefore predispose an individual to harmful infections and reduce the responsiveness to vaccines. Conversely, the low-grade inflammation that results during inflammaging is characterized by higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and C-reactive protein, and the accumulation of DAMPs57. Under these conditions, neutrophils can contribute to telomere shortening and the production of ROS, thus adding to oxidative stress and cellular aging. The clearance of dead and dying neutrophils is similarly perturbed. For example, ROS can cleave PS receptors on macrophages and reduce their efferocytosis ability58. The reduction in efficient clearance of apoptotic neutrophils and the limitation on anti-inflammatory and tolerizing effects on macrophages may exacerbate the cycle of aging and inflammation.

Part 3. Cell Life

Quiescence vs senescence

Cells of the body can enter a state of quiescence, which is a reversible state of cell cycle arrest. This allows cells to become dormant while retaining the ability to reenter the cell cycle when required for growth or tissue repair. Cell cycle arrest occurs in the G0 phase with cells retaining only the maintenance of essential functions. Markers of proliferation are reduced while cell cycle inhibitors, like p27Kip1, are elevated. Under the appropriate stimuli, typically the presence of growth factors, cells can resume their proliferative state and initiate cell division. In contrast, cell senescence is a state of permanent cell cycle arrest59. In senescence, cells are arrested in the G1 phase. Markers of cell cycle inhibition are p16INK4a and p21CIP1/WAF1 60. Senescence in culture and in the intact organism occurs through the accumulation of damage including DNA damage, oxidative stress, and activation of oncogenes. Unlike quiescent cells, arrest in the G1 phase means that cells are still metabolically active and synthesize and secrete biologically active molecules, termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP, Table 1). Cell cycle inhibitors, the SASP, and senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) characterize cell senescence.

Features and consequences of senescence

The components of the SASP include pro-inflammatory cytokines, notably IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α; chemokines, like CCL2 and CXCL8; and proteases, including MMPs61. These secreted proteins largely serve to augment the inflammatory response by recruiting and activating immune cells and remodeling the surrounding tissue. In cancer, senescent cells within solid tumors can be tumor-suppressive by limiting cell division of damaged cells that would contribute to tumor growth62. Conversely, the SASP can serve a pro-tumor function by perturbing immune cells and promoting cellular invasion of the surrounding extracellular matrix63. Therapeutic interventions have been proposed to reduce the number of senescent cells through senolytics (cell killing) or senomorphopics (cell modulation). Several such strategies can also affect immune cells and the interaction between senescent and immune cells.

Senescence and the innate immune system

While much is known about how cells of various tissues senesce during disease and aging, less is clear about cells of the innate immune system. The pro-inflammatory nature of the SASP is thought to be one of the primary contributors towards inflammaging. Ordinarily, the cells of the innate immune system, including macrophages, neutrophils, and natural killer cells can recognize and remove senescent cells. During aging, senescent cells accumulate, likely a result from deficiencies in immune clearance functions. It has been demonstrated that mice with reduced immune cell cytotoxic function had higher levels of senescent cells along with increased levels of chronic inflammatory markers64. It has also been shown that senescent cells suppress macrophage-mediated corpse removal via upregulation of CD47 which serves as a “don’t eat me” signal to macrophages65. It is therefore possible that the cumulative effects of inflammaging on immune cells form a positive feedback loop that limits senescent cell removal, increases the SASP, and contributes towards higher levels of chronic inflammation, senescence, and inflammaging66.

Macrophage senescence

While there have now been a number of reports regarding macrophage senescence67,68, it is important to distinguish between cellular senescence and the functional reduction of immune cells in the aging organism69. While it is clear that immune function (e.g. phagocytosis, cell removal, antigen presentation, etc.) is reduced upon aging in the organism, the exact nature of macrophage cellular senescence is unclear. Like much of the macrophage literature, there are a number of reports that in aged humans and mice, the macrophage exhibits an anti-inflammatory, pro-regenerative phenotype, while in other studies the converse is true69. In cell culture, stimulation of macrophages with LPS, radiation, or oxidative stress results in the classic hallmarks of senescence, i.e. – cell cycle arrest, increase of lysosomal volume, expression of the SASP, and upregulation of senescence markers such as SA-β-gal and p16INK4a. The aging of mice has also been associated with SA-β-gal and p16INK4a positive macrophage accumulation70. What is particularly disconcerting is that there is no bright line differentiating these characteristics from a pro-inflammatory macrophage that has been stimulated by LPS or IFN-γ (Table 1)71.

Senescence as a mal-adaptive macrophage mimicry

If there is little or nothing that exclusively differentiates the pro-inflammatory macrophage from a senescent macrophage, it is worth noting that many of those features are also present in other senescent cells of non-immune origin72. The SASP, reduction in proliferation, increase in lysosomal volume, and ability of non-professional phagocytotic cells to phagocytose cargo have all been shown to increase upon senescence. For example, senescent epithelial cells demonstrate increased uptake of bacteria when under oxidative stress73. It is an interesting approach to studying senescence to think of it as a process where cells adapt to perform some of the functions of immune cells74. For example, it is possible that upon damage associated with aging, chronic diseases or environmental effects, the cell clearance and efferocytosis functions of macrophages are reduced, leading to persistent low-level inflammation, and proceeding towards a mal-adaptive response in other tissue cells75. In effect, mimicking the phenotype of inflammatory macrophages trying to make up for their lost function. This process then serves in a positive feedback loop to accelerate aging of the immune system.

Part 4. Therapeutic implications (Table 2)

Senolytics

Based on the similarity between senescent cells and inflammatory macrophages, it stands to reason that senolytic or senomorphic drugs would have potent effects on cells of the immune system and indeed this is true. The first senolytic drugs in clinical trials, quercetin and dasatinib, have both reported effects on enhancing the polarization of pro-inflammatory macrophages to pro-regenerative/ anti-inflammatory macrophages76,77. Dasatinib has also been reported to deplete macrophages in solid tumors78,79. Another senolytic, fisetin, has been shown to polarize macrophages in culture away from a pro-inflammatory, LPS-induced phenotype80. While this is a rich drug discovery space, it is important to note that depleting macrophages or their inflammatory effects can have potentially widespread negative impacts on wound healing, tumor surveillance, infection resistance, and vaccine potency.

Targeting the neutrophil-macrophage interaction

Biologic approaches towards senolytics include antibodies against surface molecules like CD4781. This limits the senescent cells from evading immune system recognition in order for macrophages to remove them, but may have side effects associated with recognition of self from non-self. Along a similar approach, it may be helpful to focus on the pivotal interaction between apoptotic neutrophils and efferocytosing macrophages. For example, there are dozens of known receptor-mediated interactions facilitating recognition and engulfment. In particular, PS is recognized on apoptotic cell surfaces through the TAM family of receptors (Tyro3/Axl/MerTK) and integrins on macrophages. These receptor families engage via binding proteins, milk fat globule-EGF factor 8 (MFG-E8) bridges PS and αvβ3 integrins while growth arrest-specific protein 6 (Gas6) and protein S bridge PS and the TAM receptors. Exogenous administration of recombinant versions of these proteins or their fragments may be able to enhance efferocytosis and facilitate the transition to an anti-inflammatory phenotype while minimizing negative effects. In particular, MFG-E8 has been shown to attenuate inflammation following injury82. Therapeutic potential was demonstrated through the use of a topical recombinant MFG-E8 that accelerated the resolution of wound inflammation, enhanced angiogenesis, and decreased the time to wound closure in a diabetic wound model83.

Strategy inspired by efferocytosis of apoptotic cells

Clearly, the interaction and clearance of dead and dying neutrophils by macrophages is critical for maintenance of homeostasis and controlling the sequence of events that promote productive wound healing. To explore this process for potential therapeutic use, our group has developed a cell membrane-derived nanoparticle coating to mimic characteristic features of the apoptotic cell surface and ultimately facilitate a reduction in inflammatory macrophage response through existing physiologic pathways84. We began with poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) as a nanoparticle carrier for our membrane-derived coating, chosen for its inert, biodegradable, and biocompatible properties. We coated the surface of PLGA nanoparticles with isolated cell plasma membrane doped with exogenous, synthetic PS. Cell membranes have previously been used to coat nanoparticles, although they have provided utility through specific proteins present on the membrane surface that can interact with their environment or nearby cells85,86,87,88. In our work, we focused on the impact of the bioactive phospholipid PS, presented in the context of a generic stromal cell membrane, to mimic an apoptotic body. We demonstrated that the combination of membrane-associated proteins and PS caused a shift in macrophage phenotype from pro-inflammatory toward pro-regenerative more than PS liposomes alone. In a separate nanoparticle system, we demonstrated that even without membrane-associated proteins, PS presentation on the surface of lipid-polymer nanoparticles significantly increased phagocytosis by macrophages over nanoparticles without PS89.

PS-containing liposomes have been proposed as drug delivery vehicles to target macrophages and other antigen-presenting cells90. PS has also been proposed as a component of solid-lipid nanoparticles for RNA vaccine delivery. A concern for these strategies, as well as our cell membrane-coated polymeric nanoparticles, is the role that PS plays in blood coagulation. PS can bind coagulation proteins and participate in the coagulation cascade. Our laboratory, to translate membrane coated, PS-containing PLGA nanoparticles to an in vivo model, developed a PEGylation strategy to improve both long-term nanoparticle stability and targeting to sites of inflammation through surface functionalization91.

The lipid bilayer of our PLGA nanoparticles can be used to anchor molecules to the particle surface through hydrophobic interactions. Molecules conjugated to lipophilic moieties have been attached to cell and membrane ghost surfaces by simply incubating the molecule and membrane together and allowing hydrophobic interactions to drive insertion of the lipophilic moiety into the lipophilic portion of the membrane92,93. This process, sometimes called membrane painting, requires no additional conjugation reactions. We took advantage of the low pH of chronically inflamed sites relative to normal physiological pH28,94,95,96. Surface-functionalized nanoparticles with acid-sensitive sheddable polyethylene glycol (PEG) release can then preferentially collect/accumulate in these sites97,98,99. Results from our work show that through a membrane painting approach, particle localization to sites of inflammation in vivo was increased. These particles were also preferentially taken up by macrophages within areas of inflammation. Also, in a model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced chronic inflammation, these nanoparticles reduced inflammation and promoted a regenerative phenotype better than control nanoparticles.

Conclusions

In examining the life cycle and interactions of neutrophils and macrophages during normal homeostasis, productive wound healing, chronic inflammatory disease, and aging, it is clear that the death of neutrophils, and their clearance and efferocytosis by macrophages, play major roles in health and disease. Arguably, the clearance of neutrophils by macrophages is the most frequent immune cell interaction in the human body, and this interaction is largely immunologically invisible. Alterations in the mode and result of neutrophil death can have profound effects on macrophage phenotype and the resulting tissue environment. Similarly, a reduction in the function of the innate immune system with aging can perturb this system, resulting in low-level chronic inflammation, cell senescence, and lack of cell removal, thus contributing to a vicious cycle of inflammation. Harnessing the mechanism whereby macrophages recognize, eliminate, and polarize as a result of cell apoptosis is likely a rich search space for the development of novel drugs and drug delivery strategies.

Responses