Infrastructure development in children’s behavioral health systems of care: essential elements and implementation strategies

Introduction

The need to address the behavioral health of youth has never been more critical. Globally, increased prevalence of youth behavioral health conditions has been reported recently, particularly among adolescents1. The prevalence of youth behavioral health conditions ranges from 13–20%, costing the U.S. healthcare system approximately 247 billion dollars annually2. The most common conditions among youth include ADHD, anxiety, behavior problems, and depression, and many youth, particularly youth of color, have experienced significant trauma exposure3,4. The COVID pandemic has contributed to higher rates of externalizing and internalizing behaviors among youth and diminished caregiver well-being5. Despite increased need, more than half of youth globally with behavioral health conditions do not receive any treatment6. Those who do receive treatment are increasingly likely to do so in hospital emergency departments, raising serious concerns about the accessibility and quality of community-based behavioral healthcare systems and services for youth7. Decades of underfunding has resulted in behavioral health systems across the country existing in a nearly continuous state of crisis and unable to meet increasing demand for services. Behavioral health services are typically reimbursed at rates much lower than physical health, rates that are often insufficient to attract and retain an adequate provider network or cover the true cost of providing high-quality care8. The pandemic strained even further the behavioral health workforce, with many studies documenting increased stress, burnout, and turnover risk, further compromising the capacity to meet the demand for services9. The confluence of these factors underscores a need to address long-standing challenges in expanding and sustaining systems that can ensure the delivery of comprehensive, equitable, accessible, and high-quality behavioral health care.

Systems are comprised of interconnected elements designed to produce a particular result. They are complex, dynamic, and frequently comprised of both core elements and supporting elements. Consider transportation, for example. The core elements are easily recognizable. People want to travel for business or pleasure, and modes of transportation such as planes, trains, boats, and automobiles exist to get people there. The transportation system, however, is comprised of many additional supporting components that bind the core components together. They include well-maintained highways and roads, an adequate supply of vehicles, maintenance facilities to keep the vehicles running, trained and licensed operators, gasoline and charging stations, signs, traffic lights, and posted speed limits. Ideally, the core and supporting elements of the system work together to produce the desired results. The behavioral health system is similar. The core components of that system include youth and families in need in services, comprising approximately one in six youth, publicly operated systems, and networks of providers delivering an array of behavioral health services that vary in comprehensiveness and quality10,11.

Like the transportation system, the behavioral health system also binds its core components together through additional supporting components, referred to in this paper as infrastructure. An understanding of system infrastructure is crucially important to the field of children’s behavioral health research, policy, and practice. First, behavioral health system stakeholders continue to struggle to understand why effective interventions are not brought to scale, and why the systems in place are not producing better and more equitable access, quality, and outcomes. Many correctly point to the need for increased attention to the systems’ core components including increased funding for the provider network and a more comprehensive and effective service array. Attention to these elements is necessary, although it may not be sufficient. This paper proposes that insufficient infrastructure development may be another contributing factor to the failure of many behavioral health systems to produce better outcomes. If that is the case, then all stakeholders in the children’s behavioral health system must develop a better understanding of what constitutes critical system infrastructure and must develop effective strategies for developing and deploying those infrastructure elements.

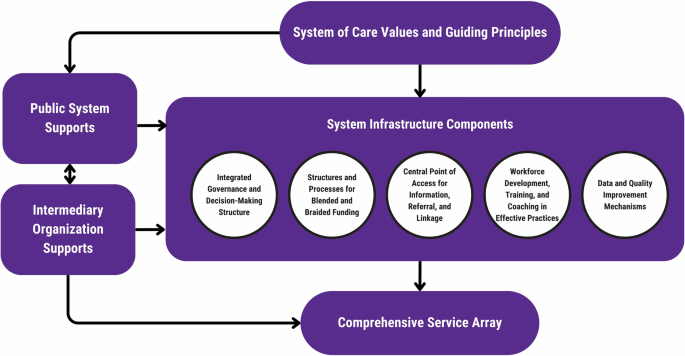

This paper defines infrastructure and places it within the context of children’s behavioral health system of care development. Prior research and scholarship identify implementation characteristics, including some infrastructure components, at the system, provider organization, individual practitioner, and child and family levels12. This paper focuses on elements of infrastructure that large public systems, such as states, are uniquely positioned to fund and deploy to the benefit of all other youth behavioral health system stakeholders. The paper then describes a set of five proposed essential elements (rather than a full and complete list) of children’s behavioral health system infrastructure: (1) an integrated governance and decision-making structure; (2) blended and braided funding; (3) a central point of access for information, referral, and linkage; (4) workforce development, training, and coaching in effective practices; and (5) data and quality improvement mechanisms. The paper ends by describing the role of public–private partnership, particularly intermediary organizations, in developing and implementing these essential infrastructure elements.

Defining behavioral health infrastructure

In the children’s behavioral health field, infrastructure is a commonly used, yet poorly defined and understood term. The “system of care” concept is an essential context for understanding system infrastructure since it has provided a guiding framework for many states to improve their children’s behavioral health delivery system. A system of care is defined as “a spectrum of effective, community-based services and supports for children and youth with or at risk for behavioral health or other challenges and their families, that is organized into a coordinated network, builds meaningful partnerships with families and youth, and addresses their cultural and linguistic needs, in order to help them to function better at home, in school, in the community, and throughout life.”13 Among the most significant contributions of the system of care concept are its aspirational set of core values and guiding principles. System of care values include being community-based, family driven, youth guided, and culturally and linguistically competent. Among its many guiding principles are access to a broad array of home- and community-based services and supports, individualized care delivered in the least restrictive environment, access to evidence-based practices, coordination across child-serving systems, and many others.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration’s system of care expansion and sustainability grant mechanism provides funding for the expansion of services as well as infrastructure development. The system of care literature depicts and describes infrastructure as the bridge between the system of care philosophy (i.e., the values and guiding principles described above) and the comprehensive array of service and supports14. Within that context, infrastructure is defined as “structures and processes for such functions as system management, data management and quality improvement, interagency partnerships, partnerships with youth and family organizations and leaders, financing, workforce development, and others.” Additional elements of children’s behavioral health infrastructure include accountability structures for policy and oversight, care and cost management, training, technical assistance, defined access and entry points, structures and processes for promoting equity, strategic planning, and others. An accompanying rating tool has been developed to assess the implementation of the values, guiding principles, and services of the system of care, including a 12-item section on infrastructure15. The extant literature therefore defines infrastructure primarily by describing its functions and activities, offering several examples of infrastructure elements.

For the purposes of this paper, infrastructure is defined as system-level structures and processes for actualizing system of care values and principles and for scaling and sustaining an effective service array. The paper expands on the notion that infrastructure serves as an important bridge between the philosophy of care and the service array by identifying its essential components. In doing so, the aim is to provide guidance for system stakeholders (e.g., state government officials, providers, consumers, advocates, and others) in directing often-limited resources for the development of the most essential infrastructure elements. The paper ends with a call for further research and scholarship to identify effective approaches to systematically enhancing infrastructure and demonstrating that such enhancements produce value-added contributions to system functioning and outcomes.

Essential elements of Children’s Behavioral Health System Infrastructure

Integrated governance and decision-making structure

The stakeholders involved in the behavioral health system are the people that put values and principles into practice and make decisions about the service array; therefore, the composition and activities of a system’s decision-making entity is perhaps the most critical infrastructure element. The children’s behavioral health system is supported by a wide range of stakeholders including youth, parents and caregivers, providers, state agency personnel, funders, researchers, advocates, legislators, policy makers, and others. At times, governance and decision-making structures include various combinations of one or more of these representatives rather than a more efficient and integrated approach bringing all stakeholders together. The result can be a very fragmented governance and decision-making structure that fails to move the system forward in a planned, coordinated, and unified manner. The system of care approach places youth and families squarely at the center of the collaborative decision-making structure with many states striving toward 50% or higher youth and family membership. Rather than being passive observers, or final reviewers of decisions that others have already made, youth and families must have full and authentic engagement in system governance and decision-making16. This often requires distinct lines of funding and support so that youth and families can fully participate in the governance and decision-making structure.

Governance and decision-making structures should be fully integrated across child-serving systems and should be public, transparent, and inclusive of all stakeholders. The executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government should be represented. Because many state agencies control one or more parts of the children’s behavioral health system, executive branch participants should include all agencies involved in funding, implementing, and overseeing children’s behavioral health services. In addition to a department of behavioral health or children’s behavioral health the governing body should include agencies responsible for child welfare, public health, physical health, education, intellectual and developmental disability, early childhood, and other areas. A state’s department of behavioral health, or occasionally a children’s cabinet, may provide lead oversight and coordination. The direct participation of each of these child-serving agencies can help to establish a singular system for all youth with behavioral health needs that simultaneously has the capacity to serve the unique needs of special populations. Interagency participation and collaboration also present opportunities for blended and braided funds to support service delivery and infrastructure. Key legislators representing relevant child-focused committees (e.g., children’s committee, health and human services, education, appropriations, public health, etc.) should also be present, along with judicial branch personnel who can ensure that the unique needs of justice-involved youth are addressed. Representatives from the state budget office, Medicaid, and the commercial insurance industry also serve as critical stakeholders.

To help achieve goals relating to equity and racial justice, members should be diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, sex, gender, language, geography, socioeconomic status, background, perspective, and other factors. Together, the integrated governance and decision-making structure can identify policy, legislative, and practice solutions to improve overall system functioning. The collaborative nature of the group can help to facilitate necessary interagency partnerships as well as agreements with private organizations such as family and youth advocacy groups. An efficient second-level structure of workgroups that aligns with the highest priorities and goals of the system allows for in-depth discussion, data review, and generating recommendations in key areas. The overarching decision-making body then reviews and considers for full implementation each of the workgroup’s activities, findings, and recommendations.

Many states’ collaborative governance and decision-making structures have formally adopted the system of care values and guiding principles, sometimes with slight modifications to reflect local priorities or other unique circumstances. Adoption of these values and principles serves to align members around a shared vision and language for the system and align state efforts within overarching federal guidance, funding, and supports. With a fully integrated collaborative decision-making structure in place, aligned around a core set of values and principles, an early task of the group is to develop a short- and long-term strategic plan that articulates a shared and prioritized set of measurable goals, objectives, and activities. The group uses system- and program-level data (described in more detail below) to guide their discussions and decisions, monitor the impacts of their decisions on system functioning and outcomes, and identify and resolve barriers. It is also frequently the role of this overarching decision-making body to develop and disseminate strategic communications, marketing materials, resources, and information to educate the public concerning the goals of the system and how to access its services and supports. To coordinate the multiple activities of a large and diverse group of system stakeholders, it is often helpful for states to engage an intermediary organization (described in more detail below). Table 1 describes an integrated governance and decision-making structure and offers several suggested implementation activities.

Structures and processes for blended and braided funding

Funding is what makes possible the realization of a system’s values and principles in the form of a comprehensive service array and adequate supporting infrastructure. The governance and decision-making structure described above, or a financing workgroup within that structure, is often charged with identifying and expanding funding to support each of these system elements and to achieve the system’s stated goals and objectives. A key challenge is to address the need for Medicaid, commercial insurance, and state grant funds to robustly cover service delivery in a way that meets the true cost of providing high-quality care, which at the provider level, involves more than the cost of direct service delivery. Therefore, a first step can be determining the true cost of delivering high-quality care, how much of that cost is supported through current financing approaches, and how identified gaps will be addressed, often by blending and braiding available funding sources. All children with behavioral health needs deserve access to the best system and services available, and many providers deliver services to youth and families with Medicaid or commercial insurance coverage, as well as the uninsured. Therefore, blended and braided funding approaches should focus on improving access to high-quality services for all, driven solely by need, and without restrictions based on insurance type, system involvement, geographic location, or other factors.

Financing approaches should include establishing regular, systematic rate review and adjustment processes to account for the increasing cost over time to deliver high-quality care. Some innovative financing models employ enhanced fee-for-service and/or value-based approaches that pay for direct service delivery costs, administrative overhead, care coordination, and the health-related social needs that significantly contribute to overall health and well-being17. These financing approaches can also incentivize identification and reduction of disparities related to race, ethnicity, language, sex, gender, and other factors. Identifying and leveraging innovative funding opportunities across all sources to support direct service delivery and infrastructure can be among the most important tasks of the collaborative governance and decision-making body.

The development and enforcement of parity laws is another important element of a comprehensive and effective financing approach. Parity generally refers to ensuring there are comparable covered services, policies and procedures, and rates between Medicaid and commercial insurance payers, and between physical and behavioral health services. Examining and improving financing approaches allows systems to address the long-standing shortfalls that have affected children’s behavioral health providers for decades, and that often force those providers to supplement reimbursement rates and grants with philanthropic support and private donations just to fill in the gaps. Medicaid and commercial fee-for-service rates typically do not support most infrastructure-related activities; rather, infrastructure funding often comes from federal, state, and philanthropic grants and contracts. Table 2 describes structures and processes for blended and braided funding and offers several suggested implementation activities.

Central point of access for information, referral, and linkage

The “no wrong door” approach associated with the system of care concept envisions that youth and families in need of behavioral health assessment and intervention have defined entry points to care, and clear and consistent information and referral protocols employed in clinical and non-clinical sectors such as schools, pediatric primary care, early care and education centers, and other settings18. The passage of federal legislation requiring states to develop 988 systems provides unique opportunities to build out this component of the infrastructure. The legislation originally envisioned 988 as a replacement for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline; however, innovative state approaches are leveraging 988 funding and implementation efforts to consolidate functions and address the long-standing need for coordinated information and referral mechanisms that are more accessible to youth and families in need of a variety of behavioral health and well-being services. In addition to meeting the needs of individuals experiencing suicidality, 988 call centers can also provide public education and information, answer questions, and connect individuals to key elements of the service array.

Many 988 call centers are establishing direct connections to elements of the crisis service continuum such as Mobile Response and Stabilization (MRSS). Upon receiving calls, texts, and chats, 988 call specialists can dispatch MRSS providers to stabilize crisis situations in the home, school, or community, who in turn provide a face-to-face assessment and help facilitate linkages to ongoing care as needed. It is critical for 988 call centers to maintain the capacity to address the unique needs of youth and their families rather than defaulting to an adult-based model; for example, by deploying face-to-face mobile response to most youth and family requests for assistance, avoiding an overreliance on referring youth to crisis receiving facilities, and making every effort to maintain youth in their homes, schools, and communities whenever that is clinically appropriate19. Several states are using the provisions of the 988 federal legislation to enact small monthly fees on wireless plans, creating a sustainable funding source for the 988 call centers and associated elements of the crisis behavioral health service array20. As with any central point of access for information, screening, and referral, systems must ensure sufficient service delivery capacity exists. Building 988 infrastructure to increase awareness and identification of behavioral health needs, without also ensuring sufficient service delivery capacity, is at best insufficient and could even be harmful to youth with behavioral health needs and their families. Table 3 describes a central point of access for information, referral, and linkage and offers several suggested implementation activities.

Workforce development, training, and coaching in effective practices

The behavioral health workforce is an area of significant need that was further weakened by the COVID-19 pandemic21. Even the most comprehensive service array will not be effective without a sufficient and well-trained workforce to deliver those services; however, many states are struggling to recruit and retain a sufficient workforce to deliver behavioral health services and supports. The available workforce frequently does not match the population they serve in terms of race, ethnicity, sex, gender, primary language, and other factors22. Some states have responded by developing comprehensive workforce development plans and making significant investments to address workforce shortages and meet the increasing demand for care. A comprehensive workforce development approach addresses short- and long-term strategies for growing and diversifying the behavioral health workforce. Interrelated actions can include sustained increases to reimbursement rates, providing grant funds to support recruitment and retention, launching a workforce coordinating center to track and monitor workforce data and implementation efforts, increasing diversity of the workforce, enhancing clinical competencies, removing unnecessary administrative and licensing barriers, incorporating peer specialists and community health workers, and increasing provider organization capacity to deliver health promotion and prevention activities23.

Workforce development includes ensuring a sufficient number and variety of providers, as well as ensuring these individuals possess the clinical competencies to address the underlying needs of the population and improve outcomes. Efforts to enhance clinical competencies must go beyond one-time training, as adult professionals require more than didactic-style trainings to develop and fully incorporate new competencies. To ensure training content is applied to direct care provision, training should be accompanied by coaching and ongoing support, opportunities to practice new skills, the addressing of underlying motivational factors, and effective supervision24. Rather than designing training and coaching approaches one service at a time, states should seek opportunities to train larger portions of the workforce in a core set of modules that tend to be related to high-quality care across many services. This may include, for example, trauma-informed practices, suicide assessment, and culturally and linguistically responsive service delivery, among others. Furthermore, as states seek to implement a single robust service array for all children with behavioral health needs, they must also attend to ensuring there are enough clinical and non-clinical staff who can address the unique needs of special populations, such as very young children, youth who are justice-involved, and youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

An important subset of training includes the dissemination of evidence-based practices (EBPs) that have been shown through rigorous research to produce positive outcomes for youth and families. The training required to effectively disseminate and sustain evidence-based treatments (EBTs) tends to be more intensive, longer-term, often employing learning collaborative or other methodologies that engage organizational senior leaders, clinicians, and family partners in one collective learning experience. As a result, distinct lines of funding (e.g., grant funds, differentially higher reimbursement rates) often are needed to support EBT implementation. Other EBPs include screening for common behavioral health conditions in schools, primary care, and other settings and systems and implementation of measurement-based care approaches25,26. While EBTs and EBPs are important parts of the service array, community-based and culturally specific practices and innovations are always being developed and delivered alongside EBTs and EBPs. Systems must have the capacity to support these innovative practices with data collection and outcomes evaluation to ensure they meet the system’s standards for quality, and that they are leading to positive, equitable outcomes. Investing in innovations and best practices in this manner may move some of these interventions closer to meeting requirements to be considered evidence based. Table 4 describes workforce development, training, and coaching in effective practices and offers several suggested implementation activities.

Data and quality improvement mechanisms

Systems and services must be guided by consistent and reliable data collection, analysis, reporting, quality assurance (QA), quality improvement (QI), and outcome evaluation strategies. In some systems, very little data is collected. In others, much data is collected but is underutilized for improving quality and outcomes. The north star for system stakeholders is to ensure equitable access, quality, and outcomes of each behavioral health service, and for the system. Frequently, provider electronic health records are insufficient for these purposes. To address this, some states have invested in data systems and require their contracted behavioral health provider network to submit data on services delivered27. State and local systems need to provide sufficient resources to providers for data collection and entry, with a focus on protecting confidentiality, collecting the minimum necessary information for QA, QI, and outcomes evaluation purposes, and avoiding inefficiency and duplicate data entry whenever possible.

Each service in the array must collect sufficient data to be able to examine whether equitable access, quality, and outcomes of care are being achieved. Socio-demographic data representing multiple dimensions of diversity allow for data disaggregation that reveals disparities in need of correction. Collecting the data is not enough. Systems must invest in the capacity to analyze, report, and use those data to provide QA, QI, and technical assistance to providers to improve overall access, quality, and outcomes for all, and to address any identified disparities. Systems should have the capacity to disaggregate data at the individual provider level as well and share it transparently with system stakeholders, which promotes accountability and public trust. Youth and families often participate in more than one service over time. Ideally, systems will have the ability to link data across services and systems, examine how youth move through the system, and identify opportunities for improving efficiency and outcomes.

In addition to using data to support and improve individual services, states should track and transparently report indicators that reflect the overall functioning of the system. Some system-level data monitoring approaches focus on distinct issues such as wait lists or uptake of EBTs, but few comprehensive systems exist. System-level data categories, each of which could include multiple indicators, may include prevalence of need, access to services, workforce, service quality, and system-level outcomes (emergency department (ED) volume, inpatient admission rates, discharge delays, waitlists, costs, etc.). Frequently, system-level indicators come from more than one system, which may suggest opportunities for integrating funding, service delivery, and data. As with data and QI processes at the service level, an equity lens should be incorporated whenever possible for system-level data collection and analysis.

System-level data dashboards have the potential to link with and yield critical insights into the service array. Monitoring wait lists, for example, can reveal the need for increased investment to increase capacity in one or more services. Identifying high rates of ED utilization among youth may reveal the need for increased investment in community-based services that divert from ED utilization, such as Mobile Response and Stabilization Services28. Examining rates of discharge delay from inpatient hospitalization, and the factors related to those delays (e.g., clinical complexity, multi-system involvement, waitlists for the recommended next level of care) can lead to expanding intermediate levels of care, improving system throughput29. Monitoring the service utilization patterns of youth with high degrees of clinical complexity and need can help in the design of tailored interventions for this population to increase access, reduce unnecessary costs, and improve outcomes. Table 5 describes data and quality improvement mechanisms and offers several suggested implementation activities.

The role of public–private partnership and intermediary organizations in addressing infrastructure needs

Public systems rarely perform all necessary infrastructure functions on their own. Returning to the example of the transportation system, a state department of transportation generally does not possess the workforce or the technical expertise to develop, operate, and maintain the entire system. Rather, they partner with a network of private sector contractors to accomplish their work. Once again, the behavioral health system is similar. States may develop and operate some parts of the service delivery system (e.g., state-operated psychiatric hospitals), and some parts of the infrastructure; however, they commonly supplement their own capabilities with a network of outside organizations that possess the technical and operational expertise to develop and implement other areas of service delivery and infrastructure.

States often turn to intermediary organizations to help them address system infrastructure needs30. Intermediaries can be housed within university departments, where they may be referred to as Centers of Excellence, independent non-profit organizations, or private for-profit consulting groups31. The literature on intermediary organizations largely grew out of the discipline of EBT dissemination and implementation science; however, the role of many intermediary organizations today extends well beyond those functions. Intermediary organizations are generally not involved in direct service delivery; rather, they possess skill and expertise in consultation, technical assistance, training, data analysis, QA, QI, policy analysis and development, dissemination and implementation science, best practice model development, and other areas32. Thus, the functions and technical skills of an intermediary overlap significantly with the essential infrastructure elements described in this paper. In fact, the case can be made that the core function of an intermediary organization is to support infrastructure development, using the variety of approaches and technical skills described above. Several infrastructure functions may come together in one intermediary organization, which can be an efficient approach for state systems. It is more common for the full complement of infrastructure supports to be provided by several intermediary organizations, ideally in coordination and collaboration with one another and with the public system. Figure 1 displays each of the five proposed system of care infrastructure components, their relationship to public systems and intermediary organizations, and their proposed function as a linkage between system of care values and the comprehensive service array.

System of care infrastructure components.

In addition to the technical skills and capabilities described above, intermediary organizations, whether they are operated within the public or private sector, must possess additional adaptive skills to be successful in their role. First, they must be expert conveners. Intermediary organizations are generally legally and operationally independent of the public behavioral health agency or agencies (e.g., a department of mental health) and independent of the direct service provider network. This affords an intermediary organization some degree of objectivity and neutrality to convene and guide a diverse group of system stakeholders. Intermediaries may regularly convene and support the project management needs of the integrated governance and decision-making structure described above. Leadership, credibility, and the ability to establish trust and buy-in are essential adaptive skills for effective convening.

Second, intermediary organizations must have significant subject matter, consultation, and communications expertise. Effective intermediary organizations should be staffed by individuals with deep knowledge and experience across multiple dimensions of the behavioral health system including policy, finance, system change, direct service delivery, data analysis, project management, and others. The intermediary organization must itself espouse the system of care values and principles guiding the entire system. Using reliable and valid sources of data and information, the expert intermediary can translate findings into comprehensive reports with actionable recommendations that articulate measurable goals, objectives, and strategies. Intermediary organizations should be highly capable grant writers and involved in bringing additional resources into the system to support their own infrastructure development activities as well as to expand and improve the service array. Intermediary organizations should be staffed by highly effective communicators who can speak and write in ways that are understandable, relevant, persuasive, and actionable to the diverse stakeholder audiences involved. Intermediary organizations often have deep expertise in policy analysis and development and can help to ensure an enabling state policy context that contributes to optimal system functioning.

Intermediary organizations with the technical and adaptive skills described above may ultimately become long-term partners in the system, rather than short-term consultants. The information and data from convening and consultation often results in detailed plans to address various needs in the system which are then implemented over a sustained timeframe. Implementation of the recommendations of those plans, particularly those recommendations directly related to implementing essential system infrastructure, may then become the ongoing work of the intermediary organization. Table 6 includes examples of intermediary organizations across the U.S. who are significantly or solely involved in developing and implementing children’s behavioral health system infrastructure.

Conclusions and future directions

Scholarship and research on systems of care propose infrastructure as one of its three primary components and as a bridge between the values and principles of the system of care and the comprehensive service array. To date, however, the existing definitions, descriptions, categorizations, and prioritizations of behavioral health system infrastructure have been insufficient for guiding system stakeholders. It is possible that lack of development and implementation of critical system infrastructure is one of the reasons children’s behavioral health interventions are not sufficiently scaled and sustained, and systems do not produce better outcomes for the children and families they are designed to serve. This paper set out to define infrastructure, categorize and describe five of its most essential elements, and identify effective approaches for promoting infrastructure development, including through public–private partnership with one or more highly skilled intermediary organizations.

Funding for dissemination and implementation research has been historically limited33. Glasgow et al. calls for a shift in investment from research on discovery and efficacy, toward research that examines the effectiveness of interventions in practical settings, and the most effective dissemination and implementation approaches for scaling and sustaining those interventions34. System infrastructure is a critical element in scaling and sustaining an array of effective interventions and ensuring this service array is accessible, is implemented with the highest quality, and produces better outcomes. There are several future directions for scholarship and research on system-level behavioral health infrastructure that would help to establish a more mature understanding of system infrastructure, framed below as a series of interrelated questions that can guide future research in this area.

-

Validity of proposed infrastructure elements. What infrastructure elements are currently in place in state systems? Are the proposed infrastructure elements viewed as valid among implementation scientists and practitioners and other system stakeholders? Are the five proposed infrastructure elements consistently present in high-performing systems?

-

Determining and assessing stages of infrastructure development. What are the stages of development for each infrastructure element? In each area, what characterizes early, intermediate, and mature development? What are the costs associated with infrastructure development and how do public systems pay for it? What are the factors that relate to advancing development of each infrastructure element over time? Can stages of infrastructure development be validly and reliably measured in a way that is sensitive to change over time?

-

The role of public private partnership in infrastructure development. In what ways have public systems collaborated with and supported intermediary organizations and other partners to develop key infrastructure elements? In what ways are intermediary organizations and other partners involved in deploying infrastructure? What are the characteristics of intermediary organizations, and the partnerships they have with public systems, that lead to optimal development and deployment of infrastructure?

-

Impact of infrastructure development. Does the presence and/or quality of each key infrastructure element relate to better knowledge, awareness, and expression of system of care values and principles among key system stakeholders? Does the presence and/or quality of each key infrastructure element relate to more comprehensive and effective service arrays? Does the presence and/or quality of each key infrastructure element relate to better outcomes for youth and families?

Responses