Insomnia and its treatments—trend analysis and publication profile of randomized clinical trials

Introduction

Insomnia is highly prevalent worldwide. It has been estimated that around 10% of the adult population presents chronic insomnia according to standardized diagnostic criteria, and about 30% of adults report insomnia-compatible symptoms1. It is a risk factor for several outcomes, including mental disorders2, metabolic syndrome3, acute myocardial infarction4 and increased mortality5. Individuals with insomnia may experience a substantial loss of quality of life due to daytime consequences6. Compared to controls, people with insomnia are up to 4.5 times more likely to have accidents, are less productive, and are more susceptible to develop psychiatric disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder and depression6,7. In addition to the individual consequences, insomnia has important economic costs. In the United States alone, total costs related to insomnia are estimated to be between U$100 to U$150 billion annually, mostly related to indirect costs such as workplace performance-related outcomes (absenteeism and presenteeism), increased health care expenditures, and a higher risk for workplace and driving accidents8,9.

Given the dimension of the burden of insomnia, there is a continuous need for the development of new therapeutic interventions. These treatments are usually categorized as either pharmacological or non-pharmacological10, and important accomplishments have been made in both domains in the last decade. Regarding pharmacological interventions, this includes the development and approval of new drug classes, such as dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs)11,12,13. Non-pharmacological interventions include the development of new cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) formats, including digital methods (dCBT-I)14,15,16, as well as the acceptance-commitment therapy for insomnia (ACT-I)17,18,19. The refinement of existing treatments, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, is also important and involves the development of new administration routes, dosage adjustments, testing in new populations and in comorbid presentations, among other activities.

The approval of these new treatments by health regulatory agencies and their implementation in public health systems depends on robust documentation regarding their efficacy, safety and clinical utility20. In this respect, the performance and publication of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is often a requirement, as RCTs are considered to be the methodological design with the highest evidence level to establish causal relationships21. The number of RCTs performed related to insomnia has been growing rapidly, reflecting the growing number of new therapeutic options for insomnia that are being proposed, developed, and made available22. However, there is a notable discrepancy between the information provided by RCTs and the prescribing practices observed in clinical settings23.

Considering the number of new interventions for insomnia being developed, tested and made available, it is important to assure they are supported by proper evidence, most importantly by RCTs. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to analyze the publication output of RCTs for the treatment of insomnia, considering both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

Methods

This study is based on a secondary analysis of data from a 2023 study to establish guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia in adults published by the Brazilian Sleep Association. The complete methods of this systematic review were published elsewhere13. The sections below use this data to focus on the aspects relevant to the current study.

The aim of the 2023 study was to identify studies investigating the effects of different insomnia treatments on adults with chronic primary insomnia. The review was based on a list of eligible interventions for the treatment of insomnia that were currently available or likely to be approved in the near future in Brazil. The list was developed by a group of experts on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia and included 42 pharmacological interventions (including herbal medicines) and 8 non-pharmacological interventions (6 presentations of CBT-I, ACT-I and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for insomnia (MBCT-I)). The list of eligible interventions is shown in Table 1.

Systematic searches were carried out in the PubMed and Web of Science databases. The search strategy combined two domains, one for insomnia and the other for the interventions (including independent search strings for each eligible intervention). Search records were imported into Covidence and deduplication was performed automatically. Articles resulting from the bibliometric search underwent a two-phase selection process. In the first phase, the titles and abstracts were evaluated, and in the second, the full text of the remaining texts was evaluated. Both processes were carried out by two out of six independent reviewers (V.A.K., A.G.B., G.L.R.C., M.P.K., I.P.A.L., and Y.M.L.), and conflicts were solved by a third reviewer (G.N.P.). The inclusion criteria, which are described in more detail elsewhere13, were as follows:

-

1.

Abstract and language: Only articles with abstracts, and published in English or Portuguese.

-

2.

Type of articles: Randomized controlled trials, including cross-over trials.

-

3.

Population: Adults with insomnia disorder, diagnosed according to ICSD-3 (International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition), DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition), or compatible manuals; or adults with moderate to severe symptoms according to the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) or the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS).

-

4.

Intervention: Any of the interventions listed in Table 1.

-

5.

Control group: No treatment, placebo or minimal intervention. In non-pharmacological interventions, those with a comparison to pharmacological interventions or CBT-I were also considered eligible.

-

6.

Outcomes: Sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency and time awake after sleep onset (WASO), measured by polysomnography (PSG) or actigraphy. Sleep quality measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), excessive daytime sleepiness measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), insomnia symptoms measured by the ISI, or the remission of a clinical diagnosis of insomnia. Specifically for non-pharmacological interventions, total sleep time, sleep latency and sleep efficiency acquired through self-report or sleep logs were also considered eligible.

In the current study, descriptive analyses are presented in four levels: (1) Considering the whole sample of RCTs, (2) Separating the RCTs between pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, (3) Considering the different pharmacological classes within the pharmacological interventions, and (4) Evaluating the therapeutical modalities independently, focusing specifically on the three with the greatest publication output. Whenever appropriate, the following metrics were estimated: year of publication of the first RCT, total number of published RCTs, average number of published RCTs per year, growth rate in the publication output, and median publication year (i.e., year in which half of the publication output has been reached).

Following, the outcome assessment methods used in each included study were analyzed. First, a list of primary outcome assessment methods was defined, and their use in the articles was evaluated. These methods were: the ISI, ESS, PSQI, clinical insomnia diagnosis, PSG, sleep diary, and self-reported sleep patterns. ISI was evaluated in three possible ways: as a raw score after treatment, as response to treatment (an ISI score reduction >7 in comparison to baseline), and as symptoms remissions (a final ISI score <8)24. Other sleep-related outcomes from the methods described in the list were also extracted. Outcomes not related to sleep were categorized using the taxonomy for outcome classification proposed by the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) database25.

Finally, the methodological quality of each study was evaluated using the van Tulder scale26. This tool is composed of 11 items related to the internal validity of trials, specifically evaluating the risk of selection, performance, detection and attrition biases (Table 2). The compliance rate was calculated as the percentage of items appropriately addressed in each article.

In all cases, numerical variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Whenever appropriate, numerical variables were analyzed using one-way analyses of variances (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test when necessary, and categoric variables were analyzed using X2 tests. All analyses were performed using JAMOVI 2.3.28, and statistical significance level was set as p < 0.05.

Results

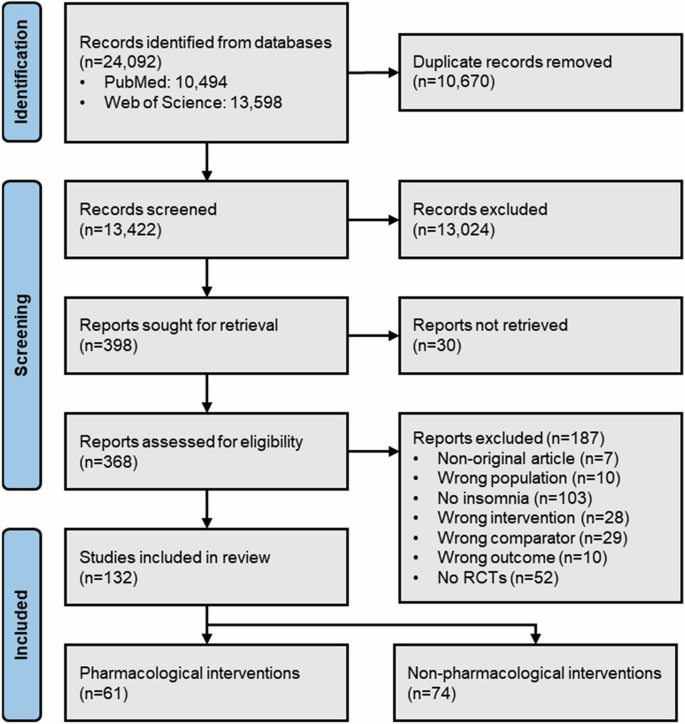

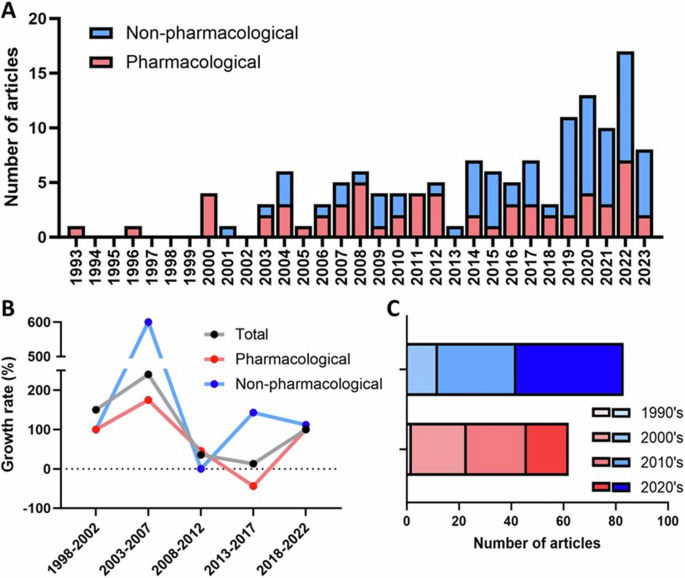

A total of 132 RCTs were included in this review (Fig. 1). Considering the whole sample of RCTs (first level of analyses), the first article included in this study was published in 1993, and only two were published by the end of the 1990s (resulting in a rate of 0.2 RCTs/year). A significant increase in the number of RCTs has been observed since then, with 32 published in the 2000s (3.2/year), 52 in the 2010s (5.2/year), and 46 published from 2020 to 2023 (9.2/year). Considering the yearly growth rate, the publication output of RCTs about insomnia has been growing at 48.0% ± 157.0% per year, but following an erratic growth pattern, as can be observed by the large standard deviation. The year with the biggest publication output was 2022 (n = 16, 12.1%). The publication output and the growth rate over time, stratified between pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, are shown in Fig. 2A, B.

Based on Drager et al.13. Three RCTs included both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. RCT randomized controlled trial.

A Publication output over time, on a yearly basis. There was an increase in the general publication rate, as well as an increase in the proportion of non-pharmacological interventions. B Growth rate of publication output over time. The analysis is made up of 5-year periods, and each point refers to the percentage increase or decrease in the number of published studies in a given 5-year period compared to the previous one. A more pronounced variation is observed in the initial years, because of the limited publication output. C Total publication output stratified per decade. The number of studies about pharmacological interventions increased in the 1990s and 2000s, but studies about non-pharmacological intervention accounted for the majority published since the 2010s.

When comparing the publication output according to the type of intervention (second level of analyses), it can be seen that non-pharmacological interventions are more common (Fig. 2C). Of the 132 included RCTs, 58 (43.9%) were related to pharmacological interventions, and 71 (57.7%) to non-pharmacological treatments (3 RCTs included both types of interventions). This difference has been driven by the increasing number of RCTs about CBT-I (particularly dCBT-I) in the past decade. This is reflected in the median year of publication, which is 2012 for pharmacological interventions, and 2019 for non-pharmacological interventions.

When pharmacological treatments are grouped by categories (third level of analyses), some patterns can be observed. The greatest number of RCTs were related to nonbenzodiazepine GABA-A agonists (or Z-drugs, n = 29, 47.5%), and 75.9% of these were on the use of zolpidem. DORAs were analyzed in 18 RCTs (29.5%), with seven related to suvorexant, seven to daridorexant, and four to seltorexant. The other classes of drugs evaluated included melatoninergic agonists (ramelteon, n = 5, 8.2%), phytotherapies (n = 5, 8.2%) and antidepressants (n = 4, 6.6%). There was no study of benzodiazepines, despite these drugs being widely used as hypnotics. There were also no studies related to anti-seizure and antipsychotic drugs.

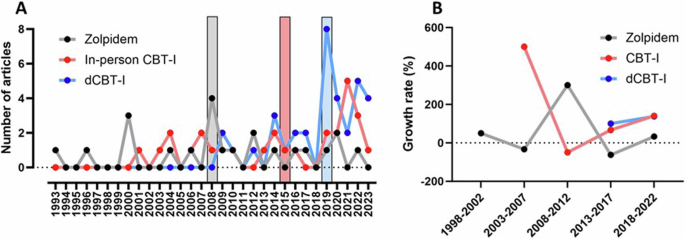

Finally, regarding the output per intervention (fourth level of analyses), the interventions with the greatest number of published RCTs were dCBT-I (n = 35, 26.5%), in-person CBT-I (n = 28, 21.2%) and zolpidem (n = 22, 16.7%). All the other interventions had significantly less RCTs, with 10 interventions having 3 to 8 RCTs each, 11 with 1 to 2 RCTs each, and 26 interventions for which no RCTs were included.

When considering the three most commonly assessed interventions, a clear time trend can be observed (Fig. 3). The first RCT about zolpidem was published in 1993, the median publication year was 2008, and 0.71 ± 0.97 RCTs were published per year. Regarding in-person CBT-I, the first RCT was published in 2001, the median publication year was 2015, and 0.90 ± 1.14 RCTs were published per year since the first RCT. For dCBT-I, the first RCT was published in 2009, the median publication year was 2019, and 1.13 ± 1.91 RCTs were published per year since the first RCT.

A Publication trend over time comparing the three interventions. The vertical bars display the median publication year of each intervention. B Growth rate on publication output over time. The analysis is made up of 5-year periods, and each point refers to the percentage increase or decrease in the number of published studies in a given 5-year period compared to the previous one. The line for each intervention begins at a different point, reflecting the fact that the application of the different interventions began at different times. CBT-I cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, dCBT-I digital CBT-I.

Among the primary outcomes, the most frequently reported one was the ISI score (n = 65, 49.2%), followed by sleep diary measures (n = 63, 47.7%), and PSG outcomes (n = 41, 31.1%). ISI-based response to treatment and symptoms remissions were not commonly reported, although being reputed to be a reliable measure of insomnia treatment outcomes20. ISI-based response to treatment was reported in 9 studies (6.8%), and remissions were reported in 12 studies (9.1%). Additional sleep-related outcomes were reported by 80 RCTs, and included 36 different outcome measurements. The most widely used non-primary outcome was the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale (DBAS) (n = 25, 18.93%), while all the others were used in no more than five RCTs. ISI as score, ISI as remission, sleep diary, DBAS and PSQI were significantly more frequently reported on RCTs of non-pharmacological interventions, while self-reported sleep measures were more frequently reported on pharmacological trials (p < 0.05).

When considering outcomes not related to sleep according to the COMET classification25, the most often reported were emotional functioning/well-being (n = 50, 37.9%), physical functioning (n = 18, 13.6%), cognitive functioning (n = 16, 12.1%) and delivery of care (n = 15, 11.4%), while all the remaining outcome categories were reported by less than 10 RCTs. Emotional function/well-being and delivery of care were significantly more often reported on RCTs of non-pharmacological interventions, while cognitive functioning was more frequently reported on pharmacological trials (p < 0.05). The complete results of the outcome analyses between pharmacological and non-pharmacological trials are available in Table 3.

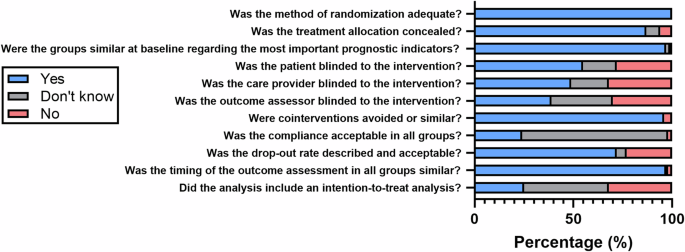

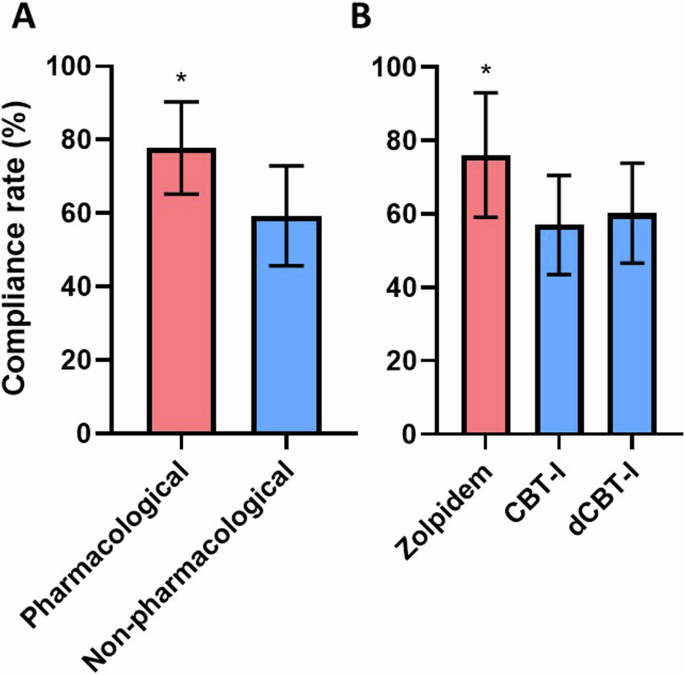

The average compliance rate among the 132 articles items in the van Tulder scale was 67.4 ± 15.9%. It was observed that 100% (n = 132) of the RCTs reported being properly randomized. This result is explained by the fact that being randomized was an inclusion criterion in the eligibility criteria. The highest compliance rates in the whole sample were observed on van Tulder’s item #10 (similar outcome assessments timing, n = 128, 96.7%), #3 (similar baseline characteristics, n = 128, 96.7%) and #7 (absence of cointerventions, n = 127, 96.2%). Lower ones were observed on item #8 (compliance acceptable among groups, n = 32, 24.2%), and #11 (intention-to-treat analyses, n = 33, 25.0%). The compliance rates for each of the 11 items in the van Tulder scale are described in Fig. 4.

Evaluation was performed using the van Tulder scale26.

The average methodological compliance rate was significantly higher among RCTs of pharmacological interventions in comparison to non-pharmacological ones (p < 0.001, Fig. 5A). RCTs of pharmacological interventions were significantly associated with higher methodological quality in van Tulder’s item #2 (allocation concealment), #4 (patient blinding), #5 (care provider blinding), #6 (outcome assessor blinding), and #7 (cointerventions). Complete results of the analyses of methodological quality between pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions are available in Table 2. Considering the three most reported interventions, the average methodological compliance rate was significantly higher in RCTs about zolpidem in comparison to both in-person CBT-I and dCBT-I (p < 0.001), while there was no difference between CBT-I and dCBT-I (p = 0.706, Fig. 5B).

A Comparison between RCTs of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. *p > 0.001 at the one-way ANOVA. B Comparison among the three most frequent interventions for insomnia. *p > 0.001 at both one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that the number of RCTs for treatments for insomnia has been growing significantly. RCTs of pharmacological treatments accounted for the majority of publications in the 1990s. In the 2000s, studies on non-pharmacological interventions began to appear, and nowadays, they represent the majority of publications for insomnia treatments. In this regard, an interesting finding is the surge in the number of RCTs about dCBT-I, the intervention with the most published studies (n = 35).

This increase in the number of RCTs for digital therapies for insomnia can be understood from several perspectives. First, this can simply be because these interventions have been developed more recently, and therefore, it is natural that current research focuses more on newer interventions, rather than continuously testing older ones. Also, the scientific publishing environment has been changing as a result of the current infodemic, and the publish-or-perish paradigm. It is interesting to note that the amount of RCTs for dCBT-I in the last couple of years surpasses the amount of research for most of the pharmacological therapies available in the whole period. However, it should be borne in mind that some pharmacological therapies, such as the use of DORAs, are relatively recent, and that the publication profile in respect of these treatments has not caught up with their use.

Beyond the general changes with respect to scientific publishing, which we described above, we can suggest three possible hypotheses to explain the increase in the number of RCTs in this area. The first relates to the need for RCTs in respect of pharmacological treatments to be performed in order to register a new drug and attest to its safety and efficacy, although if other pharmaceutical companies release their presentation of the same drug, new RCTs are not needed. In other words, as long as the chemical compound, dosage and administration route of a drug does not change significantly, the RCTs published by the first pharmaceutical company are usually considered sufficient and valid for the presentations developed by other companies. However, depending on the legislation, some control quality tests, bioequivalence studies and other assessments might be needed, but these are not necessarily published as peer-reviewed papers or RCTs. The contrary has been observed in respect of dCBT-I apps and platforms, with each company developing digital interventions pursuing the publication of RCTs on their own product, in order to position it in the market and promote it as being “evidence-based”, which can be used as a marketing strategy27. There is also an important regulatory aspect because the regulation of software as medical devices (SaMD) is still an area of uncertainty, and this may be driving many companies to conduct their own RCTs rather than relying on the results from other apps and companies.

A second hypothesis is based on the patient’s experience with treatment. There are a growing number of reports of adverse events from common insomnia medications28, and even non-pharmacological interventions, such as sleep restriction, can result in fatigue, drowsiness and attention problems during the initial phase of treatment29,30. The adverse effects of traditional pharmacological treatments have encouraged the search for safer alternatives, such as CBT-I, which have low evidence of side effects and are safe and effective in the long term28. This seems to have been a factor that contributed to the increase in studies around CBT-I, and the need to make it more accessible may have influenced the increase in studies using dCBT-I.

Finally, the surge in RCTs on dCBT-I may be because of the nature and diversity of these interventions. Unlike drug compounds, which are similar (meaning that performing multiple RCTs may be unnecessary unless there are significant changes in dosage or administration routes), dCBT-I apps may be substantially different27. These differences can include variations in the psychotherapeutic approach, the number and sequence of modules, the strategies within each module, additional features and integration with other devices (mainly wearables). Thus, it is necessary to have independent RCTs for each dCBT-I because of their lack of similarities

Other aspects of our results also deserve attention beyond those for dCBT-I apps, especially with respect to the publication of RCTs about pharmacological treatments for insomnia. While our data showed a reduction in the proportion of these over the past decades, there is a general consensus that drug research needs to be expanded in this area31 to fill gaps in the literature about pharmacological treatments for insomnia. It should be noted that most of the potential pharmacological interventions identified were not analyzed in any RCT, and many of them by no more than one or two RCTs (Table 1). The most remarkable example of this is in respect of benzodiazepines, which despite being historically important hypnotics and still highly prescribed for insomnia, have been the subject of few RCTs. A similar pattern is observed for anti-seizure, antipsychotic and antidepressant medications. Two notable exceptions to this are zolpidem, for which we found 22 RCTs, possibly explained by the diversity of commercial presentations available, and DORAs, which are a more recent pharmacological class. The lack of RCTs is not only restricted to the drug categories being assessed, but also to the population being studied in these trials; for example, there are few RCTs for insomnia treatments in specific populations, such as children, older adults, and people with comorbidities, as has been reported in previous studies32. In addition, there is a lack of longer-term RCTs that look at the side effects of the concomitant use of these drugs with other drugs, such as antidepressants and antipsychotics32.

A number of other issues have been raised regarding the methods employed in RCTs for pharmacological treatments for insomnia. First, the representativeness of the samples used in RCTs for the pharmacological treatment of insomnia has been questioned, which might have implications with respect to the assessment of their efficacy and safety33. Most participants in insomnia RCTs are highly screened by inclusion and exclusion criteria, in a way that results in the samples in these trials hardly representing the real population of individuals with insomnia. It is estimated that only 0.4% of insomnia patients would comply with the eligibility currently imposed by most RCTs34. Future studies need to have less restrictive eligibility criteria to filter outside effects before commercialization. Finally, another concern regards the differentiation between insomnia disorders and insomnia symptoms. A recent review35 reported that 90% of RCTs and systematic reviews did not clearly describe in the abstract whether the object investigated was insomnia disorder or insomnia symptoms. When analyzing the full texts, 27% of the RCTs and 57% of the reviews did not provide any further clarification. This highlights the importance of properly defining insomnia, as the clinical course of insomnia disorder is different from cases of insomnia symptoms, which might happen as a symptom of many other medical and psychiatric conditions.

Regarding quality assessment, it became clear that the methodological quality and internal validity of RCTs of pharmacological interventions were higher than among those of non-pharmacological interventions. Part of it might be explained by factors intrinsically related to how interventions are applied in each case. As an example, allocation concealment and patient blinding are not easily implemented in trials of cognitive-behavioral interventions. This reinforces the need for more robust methodological control of non-pharmacological interventions for insomnia. In any case, the level of methodological quality among RCTs of non-pharmacological interventions does not seem to be sufficiently higher to compromise their results.

Interesting conclusions can also be seen in the type of outcomes reported in each type of RCT. ISI, both as a score and as symptoms remission, has been more often reported among trials of non-pharmacological interventions. This may be explained by tradition in each type of research, as this tool and the way to calculate its derived outcomes24,36 have been proposed by the research groups that have initially validated CBT-I and worked on some of its early adaptations to digital forms20,24,37,38,39,40. On the other hand, polysomnographic variables as outcomes have been reported more often by RCTs of pharmacological interventions.

This study has some limitations and methodological considerations that should be noted. First, many studies that make up the body of evidence with respect to the treatment of insomnia were not included in the current study. This reflects the strict inclusion criteria used, which limited the studies to those about insomnia in adults with no comorbidities, including a rigorous list of outcomes and a defined control group. Cases of insomnia associated with other conditions (including anxiety and depression) were excluded. This explains the limited publication output with respect to anti-seizure, antipsychotic, antidepressant, and benzodiazepine drugs, whose indication is most appropriate in cases with comorbidities. Second, this review was focused on drugs that are currently available, or are likely to be approved in Brazil in the near future, which resulted in the exclusion of some drugs that are considered to be the recommended treatments for insomnia in other countries. The most important drugs not included for this reason were temazepan and zaleplon (not approved for use in Brazil). Likewise, non-pharmacological interventions for insomnia not listed in the original study were not included in the current manuscript. This resulted in the omission of potentially important non-pharmacological treatments for insomnia for which RCTs have already been published, especially single component behavioral interventions, such as sleep restriction therapy and brief behavioral therapy.

In conclusion, the output of RCTs on interventions for the treatment of insomnia has been growing steadily. A substantial publication record was observed for zolpidem, and a growing number of RCTs on DORAs was also identified. However, the main reason for the surge in the number of RCTs was the increasing number with respect to CBT-I (mostly in the 2000s) and digital interventions (mostly in the last decade). The increase in this number is useful from an evidence-based perspective, as the availability of more data allows a better appraisal of the current evidence, and the performance of data synthesis approaches, such as meta-analysis. In despite of the bigger publication output, the methodological quality of RCTs of non-pharmacological interventions is reduced in comparison to pharmacological trials. The commercial influence on the publication of these RCTs cannot be denied. This is not necessarily something that is inappropriate, and no cases of sponsorship bias or malpractice have as yet been identified. Rather, this is more likely to be the adaption of the scientific community and the research profile to a new modality of treatment for which many uncertainties still exist, both on the clinical and regulatory aspects. Researchers should be attentive to new RCTs published about therapeutic interventions for insomnia, assuring that the unavoidable growth in the number of published articles happens in a reliable and responsible manner, not leading to a reduction in the methodological quality.

Responses