Intellectual property information literacy education: evidence from 30 Chinese National IP Demonstration Universities

Introduction

In the era of knowledge economy, effective IP utilization is crucial for advancing scientific innovation, economic growth, and sustainable development (WIPO, 2023). Equipping young people, the main drivers of future innovation, with skills in acquiring, analyzing, protecting, using, and managing IP information enhances personal potential and innovation capabilities (WIPO, 2023) and bolsters national competitiveness. Thus, fostering IP information literacy is deemed essential for national talent development and innovation (Li and Liu, 2022; Tsvetkova et al.,2021), has become a significant concern for universities and IP organizations. The World Intellectual Property Organization (2024), the United States Patent and Trademark Office (2023), and the European Union IP Office (2019) have implemented targeted educational initiatives through various programs.

China has been systematically advancing IP information literacy education through comprehensive policy initiatives. The National IP Strategy Outline (The State Council of China, 2008) advocated integrating IP courses into higher education curricula and incorporating IP education into the broader quality education framework for university students. In 2012, the Ministry of Education (MOE) designated the IP as a special major within the law discipline. A few years later, the term “IP information literacy education” was officially introduced in the Implementation Measures for the Construction of IP Information Service Centers in Universities (MOE, 2018). The National Standards for Undergraduate Program Teaching Quality in Regular Higher Education Institutions mandated that “IP literature retrieval and application” be a core course for the IP major (MOE, 2018). In October 2020, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA, 2020) and MOE jointly launched an initiative to enhance IP capacity in higher education institutions. Through a rigorous selection process involving application, recommendation, and evaluation, 30 universities were selected and recognized as Chinese National IP Demonstration Universities for their outstanding performance in IP education and management. This initiative has ushered in a paradigm of nation-directed, systematically planned, and phased advancement in IP higher education. In the latest “14th Five-Year Plan for IP Talent” (2021), the CNIPA continues to emphasize the role of universities as critical bases for cultivating high-level IP talent. The plan stresses the importance of integrating theory with practice, enhancing practical skills, and improving capabilities in IP information management, retrieval, and intelligence analysis (The State Council of China, 2022). Additionally, other significant documents, such as the “Outline for Building a Powerful Country with Intellectual Property Rights (2021–2035)”, underscore the importance of universities in the development of IP talent (The State Council of China, 2021).

However, despite policy initiatives, surveys indicate university students’ limited understanding of IP information (Ma et al., 2024; Tinao et al., 2018; Wang, 2020; Zhao, 2020), revealing a gap between policy goals and educational outcomes. This raises key research questions: How exactly is IP information literacy education being implemented in Chinese universities? What are its current characteristics and challenges? How can this education be enhanced to better serve students’ needs?

We propose that the 30 National IP Demonstration Universities could serve as a representative sample for investigating these issues. These universities lead the field of IP information literacy education, offering specialized courses alongside libraries’ educational practices. Our research employs a web-based research approach supplemented by email surveys, with descriptive analysis. Specifically, we conducted systematic web-based searches of 30 universities and their libraries, supplemented by three targeted email surveys, to collect detailed data on courses and library practices. A descriptive analysis was subsequently conducted to explore the collected data and information thoroughly, providing a comprehensive response to the research questions previously outlined.

After reviewing the literature in both Chinese and English, we identified four main gaps in the existing research: (1) There is a lack of consensus in academia on the definition of IP information literacy, with some misunderstandings persisting. (2) Few studies have focused specifically on IP information literacy education in universities, and no comprehensive study has been conducted on China’s 30 National IP Demonstration Universities. Most research centers on IP literacy education more broadly. (3) Studies on university IP information literacy courses lack detailed data and rigorous analysis, often failing to explore microlevel aspects such as course content, with most research offering only general descriptions of patent information courses. (4) Most of the research in this field concentrates on libraries, examining aspects such as websites, resource types, outreach, training, and lectures, but often overlooks a holistic approach that integrates cross-departmental resources.

This study presents the first comprehensive analysis of IP information literacy education in Chinese universities. It contributes by clearly defining “IP information literacy,” addressing academic misconceptions, and providing actionable insights for policymakers, educators, and librarians. The findings offer valuable references for international IP information literacy education development in universities.

Literature review

Intellectual property and information literacy

According to the widely accepted definition provided by the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (WTO, 1994), intellectual property (IP) includes copyright and related rights, trademarks, geographical indications, industrial designs, patents, layout designs (topographies) of integrated circuits, and undisclosed information.

Information literacy, introduced by Zurkowski (1974), has evolved into a globally recognized critical competency involving the ability to “find what is known or knowable on any subject.” Key frameworks from the American Library Association (ALA, 1989), the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL, 2000; ACRL, 2016), the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals of the United Kingdom (CILIP, 2012), the European Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp2.2) (Vuorikari et al., 2022), China’s Ministry of Education (MOE, 2018; MOE, 2021) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2013) emphasize various aspects: ALA and ACRL (2000) emphasize technical skills; CILIP stresses critical judgment; and both UNESCO and the EU define information literacy in conjunction with other elements. China’s frameworks emphasize the practical application of information literacy. We favor ACRL’s (2016) definition because it provides a comprehensive framework. According to this definition, information literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

IP literacy education

IP literacy is defined and interpreted in various ways across different academic and regulatory contexts. Tyhurst (2018) adapts the ALA’s information literacy model, but this approach fails to capture the full complexity of IP literacy. Wu et al. (2017) include IP awareness and competence, whereas Fu et al. (2009) emphasize applying IP laws for rights protection. Broader views involve problem-solving with IP knowledge (Li, 2022; Li and Chen, 2008) and intangible asset protection (Viana and Maicher, 2014). Qin and Tian (2024) stress understanding and applying IP concepts. In China, although CNIPA emphasizes IP literacy education through five regulations, a clear and precise definition remains absent. The most recent regulation (CNIPA, 2024) identifies key components, including fundamental IP knowledge, legal understanding, and practical skills in analyzing and applying IP information.

The diverse definitions and interpretations of IP literacy underscore its multifaceted nature. Based on the existing literature and regulations, we propose the following definition of IP literacy: it is an integrated set of awareness and skills that includes understanding the impact and responsibilities of the IP on society, the economy, and culture; creating, identifying, using, and managing various forms of the IP (such as patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets); adhering to IP-related laws, ethics, and moral principles; retrieving, analyzing, and applying IP information; and addressing other IP-related issues. This comprehensive definition supports educational initiatives by encompassing essential elements from understanding to application, clarifying legal and social responsibilities, and ensuring accessibility for beginners. We concur with Li (2022) that IP literacy education encompasses all education related to IP literacy.

We align with scholars who use “IP literacy education” and “IP education” interchangeably (Zhang and Peng, 2024; Chen et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2009; Qiu, 2018). Studies on IP awareness (Balahadia et al., 2022; Meng and Meng, 2011; Ong et al., 2012; WIPO-CDIP, 2022), IP management (Fishman, 2010), copyright literacy (Shi, 2019), and patent knowledge (Ma et al., 2024; Zhao, 2020) fit within our defined scope of IP literacy.

Some LIS scholars view IP literacy as a subset of information literacy (Chen and Luo, 2021; Li, 2022; Liu, 2022). They argue that it is foundational or crucial to information literacy (Li and Chen, 2008; Denchev and Trencheva, 2016; Denchev and Trencheva, 2016; Trencheva, 2020; Wickramanayake, 2016). However, we contend that this view is problematic, as IP literacy and information literacy only partially overlap. IP literacy is more specialized, encompassing IP law, procedures, rights protection, management, and evaluation, whereas information literacy addresses general information. The fact that more Chinese universities offer IP courses or degrees in law schools than in information schools further supports this distinction.

China’s higher education system for IP talent spans undergraduate to doctoral programs (Chen et al., 2022), but it primarily trains specialists, neglecting the needs of general students (Lin et al., 2010). Studies have indicated limited IP awareness (Chen et al., 2012), inadequate understanding of IP law (Yang, 2015), insufficient patent knowledge among postgraduates (Ma et al., 2024; Zhao, 2020), and poor comprehension of copyright issues in digital contexts (Zhang, 2015). Challenges include outdated content, reliance on traditional methods (Peng and Liu, 2023), and a lack of interdisciplinary focus (Guo et al., 2009). Students show interest in learning about IP but face limited opportunities (Wu et al., 2015). Proposed solutions include mandatory IP courses (Jiang et al., 2013), “student-centered” teaching methods (Xu, 2012), practical course design (Zhou, 2018), and a “two-stage study model (3 years + 2 years)” (He, 2022). Other suggestions include integrating IP education with innovation-focused curricula (Chen et al., 2022), and strengthening IP programs at technical universities (Liu, 2022; Lu et al., 2023; Qiu et al., 2021). Some studies indicate that university libraries are key to IP literacy education, contributing to talent development and protection services (Zhang and Peng, 2024). Chang et al. (2021) recommended the multitiered model of the Chongqing University library, and others suggest comprehensive frameworks (Liu, 2022) and interdepartmental collaboration (Wang and Lin, 2023).

Scholars worldwide have identified deficiencies in university IP literacy education, including in countries such as Spain (Coello et al., 2020; Muriel-Torrado and Fernández-Molina, 2015), France (Boustany and Mahé, 2015), Iceland (Pálsdóttir, 2019), the Philippines (Balahadia et al., 2022), India (Reenborne and Khongtim, 2022; Vasudevan and Suchithra, 2013), Ghana (Glover and Korletey, 2016), Nigeria (Igudia and Hamzat, 2016), and the United States (Charbonneau and Priehs, 2014; Fernández-Molina et al., 2022). Tinao et al. (2018) found that students show strong interest in topics such as IP overviews, patents, copyrights, design rights, and plagiarism, seeking greater curriculum integration. Recommendations include enhancing teaching methods (Penaluna and Penaluna, 2023), incorporating specific IP modules in undergraduate curricula (Gimenez et al., 2012), and conducting early and systematic IP education (Todorova and Peteva, 2013). Other suggestions include mandating IP literacy training across all degree programs (Dimitrova et al., 2020), increasing focus on practical IP usage (Wenturewell, 2020), and developing IP maps for skill assessment (Denchev et al., 2021).

IP information literacy education

Research on IP information literacy education in China is limited, with only five publications between 2021 and 2024 (Cai and Li, 2024; Chen and Luo, 2021; Li and Liu, 2022; Xu and Yuan, 2023; Xu et al., 2021), all of which originate from the LIS field and focusing on libraries. Other related studies address certain aspects of this topic. Our literature review identified three main themes: the definition of IP information literacy, library educational practices, and IP information literacy courses.

Definition of IP information literacy

The academic community has yet to reach a unified definition of IP information literacy. Stock and Stock (2014) propose a broad framework encompassing law, science, technology, and economics, but this breadth dilutes clarity and risks confusion with “IP knowledge”. Some researchers conflate IP information literacy with IP literacy (E and Ma, 2020; Zhang and Bao, 2022; Zhang and Peng, 2024). Following Liu’s (2022) approach to positioning IP information skills within IP literacy, we propose that IP information literacy should be more narrowly defined to avoid confusion with broader concepts of IP literacy.

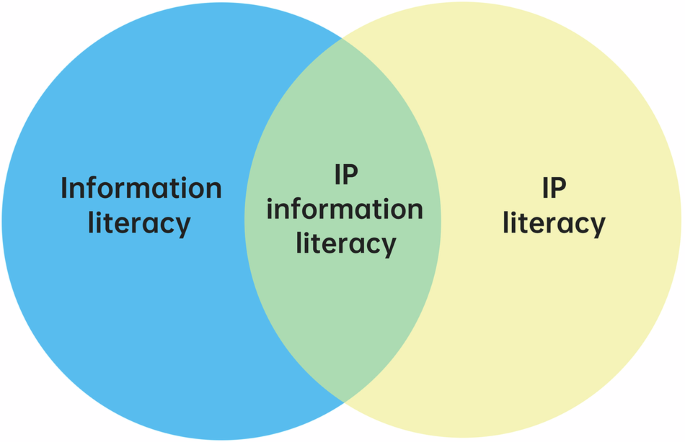

This study posits that IP information literacy lies at the intersection of information and IP literacy (see Fig. 1), integrating skills in information retrieval, analysis, evaluation, and application with specialized knowledge in IP. We define IP information literacy as a set of skills and awareness that include: understanding the societal, economic, and cultural value of IP information; effectively retrieving, analyzing, evaluating, using, and managing various forms of IP information (e.g., patents, copyrights, trademarks); adhering to IP-related laws, ethics, and moral principles; and utilizing IP information to generate new knowledge and participate ethically in learning communities. This definition clarifies its relationship to both IP literacy and information literacy, ensuring focus and clarity for both research and educational purposes.

The relationship between information literacy, IP literacy, and IP information literacy.

IP information literacy education in libraries

The literature on IP information literacy primarily focuses on library practices, which can be categorized into three areas: dedicated IP information literacy education, IP information services that include literacy education, and IP literacy education that incorporates information components. The core findings underscore the pivotal role of libraries in IP information literacy education. Xu et al. (2021) identified three key modules: diverse learning pathways, outreach media, and learning outcome evaluations. Educational delivery includes traditional methods and digital platforms. Specifically, online micro-courses and WeChat content provide efficient, mobile learning solutions (Xu, 2019; Chen and Luo, 2021; Xu and Yuan, 2023).

Despite educational initiatives, current IP information literacy education in libraries faces several challenges: a shortage of specialists (Li and Liu, 2022), disorganized online resources, and unsystematic content (Song, 2022). The proposed solutions include comprehensive frameworks (E and Ma, 2020), multilevel educational models (Liu and Li, 2020), integrated learning platforms (Zhou et al., 2019), and “learn-compete-create” systems (Cai and Li, 2024). Considering the complexity and value of patent information, scholars emphasize improving patent information literacy through research-embedded services (Wang et al., 2015), improved resource organization (Liao and Zhou, 2022), systematic navigation (Zhang and Shan, 2021), and inter-library alliances (Yan, 2019).

IP information literacy courses

Despite the designation of “IP literature retrieval and application” as a core course for the IP major, it is challenged by outdated curricula and insufficient resources (Zhao et al., 2023). Patent information literacy education is particularly deficient in universities, as evidenced by surveys demonstrating limited patent awareness among students in fields such as traditional Chinese medicine (Yang et al., 2011), medicine (Zhao, 2020), and engineering (Gu and He, 2013; Wang et al., 2011). To address this deficiency, scholars advocate for multidisciplinary approaches integrating IP engineers, patent agents, and legal experts (Gu and He, 2013); emphasize practical skills in analyzing, utilizing, and applying patent literature (Wang et al., 2011); and recommend tailoring course content to the specific needs of diverse student groups (Zwicky, 2019).

Methods

Prior research has predominantly relied on publicly available data accessed through online searches, with subsequent descriptive analysis employed for data interpretation. These studies address several topics, including educational practices in libraries and IP information service centers (Liu et al., 2022; Liu, 2022; Xu, 2019; Xu et al., 2021), comparative analyzes between Chinese universities and international counterparts (Cui, 2021; Wang and Lin, 2023), and the operational practices of IP information institutions in Germany (Lei et al., 2021), the United States (Feng, 2017), and Japan (Zhao and Xu, 2021). This approach is posited to enhance both research validity and practical relevance.

Case studies focusing on specific university libraries, including Peking University (Liu and Li, 2020), Hefei University of Technology (Cai and Li, 2024), Chongqing University (Chang et al., 2021), and Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (Li et al., 2020), offer valuable practical insights, but their generalizability may be limited by the researchers’ primary affiliation as librarians.

While our study primarily relied on web-based searches, we supplemented our data collection by conducting email surveys with three students when course information was not available online. Aligning with our definition of IP information literacy education, we carefully selected relevant courses, databases, training, lectures, and micro-courses. Data were collected from July to September 2022 and subsequently updated from March to August 2024. Due to website redesign at some institutions, certain web pages that were previously accessible are no longer available. Consequently, in Tables 1–4, we have retained the original access dates for pages that are no longer accessible, while updating the access dates for those pages that remain available.

Specifically, two core datasets were collected from 30 National IP Demonstration Universities:

The first dataset comprises IP information literacy courses offered at these universities. Course information was gathered from three publicly available sources: (1) the universities’ academic administration websites; (2) the education programs published on the websites of their respective schools; and (3) curricula available on library websites (see Tables 1 and 4). The majority of courses were obtained from sources (1) and (2). For three universities where course information was not publicly accessible (Tongji University, Chongqing University, and Hunan University), enrolled students were contacted via email to complete the dataset. These students, familiar with IP, referenced course descriptions and followed our definition of IP information literacy. We conducted a secondary review to verify the accuracy of the data.

All course materials were thoroughly reviewed, and only those directly related to IP information literacy were retained. Courses focused on IP law, patent law, trademark law, and copyright law were excluded, as they did not address IP information. Fourteen courses lacking explicit IP information keywords in their titles were included based on their substantive relevance (see Table 5). The analysis framework encompassed seven dimensions: educational level, availability, offering secondary unit, title, type, credit, class hour, and content.

The second dataset investigates IP information literacy practices in libraries across 30 universities and is divided into two parts. The first part catalogs the libraries’ IP databases, categorized based on systematic searches of each library’s website (see Tables 2, 4 and 7). The second part details both online and offline IP information literacy training, lectures and micro-courses (see Tables 3, 4 and 6), encompassing online learning resources accessible via library websites and official WeChat accounts, alongside offline training and lectures identified through the “Event Notices” or “News” sections.

While the aforementioned educational practices and resources may not comprehensively encompass the entirety of IP information literacy education, they represent significant, resource-intensive endeavors. These initiatives, demanding considerable human and financial investment, exhibit notable representativeness and stability, effectively illustrating the efforts and distinctive approaches undertaken by each university in this domain. Sporadic and non-routine educational activities were excluded from this study due to their limited accessibility and individual-driven nature. Such activities, including informal student–teacher meetings, independent project research, and ad hoc competition guidance, typically lack broad applicability and sustained continuity, thereby falling outside the defined scope of this research.

This study adhered to rigorous ethical standards. Publicly accessible data served as the primary source, ensuring data integrity and minimizing potential ethical concerns. For the student email surveys, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Practices of IP information literacy education at 30 universities

IP information literacy courses at 30 universities

IP information literacy courses are critical for enhancing educational effectiveness and achieving desired learning outcomes. The data indicate that 25 out of the 30 universities (83%) offer IP information literacy courses, with a total of 33 courses offered. However, five universities—Beihang, Sun Yat-sen, Southeast China, Jiangnan, and China University of Mining and Technology—do not offer these courses.

Course types, credits, and class hours

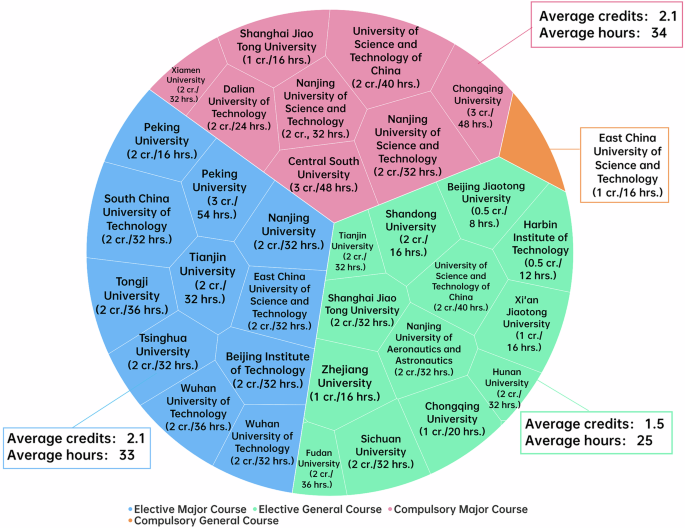

To provide a comprehensive overview of the course offerings, Fig. 2 illustrates the distribution of course types, credit allocations, and class hours across the 30 Chinese universities included in this study.

Course types, credits, and class hours.

A total of 13 elective general courses are offered by 13 universities, averaging 1.5 credit points and 25 class hours. Resource allocation for these courses varies across universities, resulting in a credit range from 0.5 to 2.0. These courses are designed to allow students the flexibility to select subjects of interest, thereby broadening their knowledge base.

Eleven elective major courses are provided by nine universities, averaging 2.1 credits and 33 class hours. Notably, the “Patent literature retrieval” course offered by Peking University Law School for graduate students stands out with 54 class hours, the highest among the courses. This indicates that these universities view IP information literacy as a critical component of certain majors, motivating students to invest more time and effort in these subjects.

There are eight compulsory major courses offered by seven universities, each with an average of 2.1 credits and 34 class hours. Certain majors at these universities place a strong emphasis on IP information literacy education, requiring students to complete their coursework.

East China University of Science and Technology offers the only compulsory general course, which carries 1.0 credits and 16 class hours. This course is mandatory for all undergraduates, as it aims to equip them with essential knowledge and skills related to IP information.

Overall, the design of IP information literacy courses is characterized by diversity and flexibility, balancing both general and specialized education. Notably, four universities combine general education with specialized education. Variations in credit and class hours reflect the different levels of importance that universities attach to this field. Predominantly offered as electives, including both elective major courses and elective general courses, this subject is generally regarded by universities as “important but not essential,” giving students greater autonomy in course selection. Only a few universities make these courses compulsory, and there is a notable scarcity of compulsory general education in this area, resulting in limited coverage of IP information literacy courses.

Secondary units offering courses

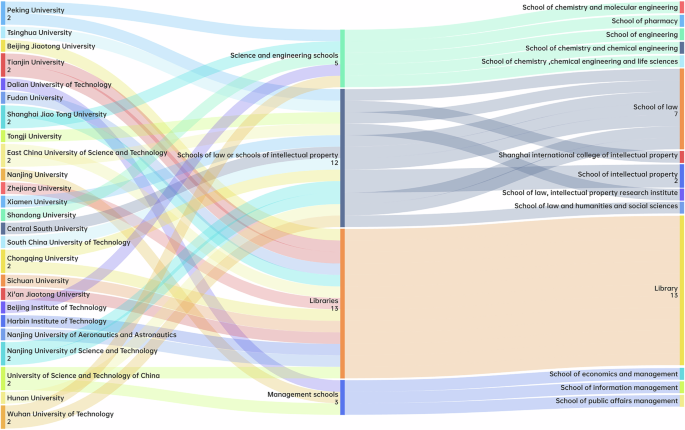

Among the 25 universities offering IP information literacy courses, the responsible secondary units are categorized into four groups: libraries, law/IP schools, science and engineering schools, and management schools (see Fig. 3). Each unit leverages its specialized strengths to deliver these courses.

Secondary units offering courses at 30 universities.

Libraries (39%): Thirteen courses offered by 12 libraries focus on information retrieval and analysis, typically integrating IP content into broader information literacy courses. Only three libraries offer dedicated IP information courses.

Schools of law/IP (36%): Twelve courses offered by 11 universities align with the Ministry of Education’s classification of IP as a major under the category of law.

Science & Engineering Schools (15%): Five schools provide courses emphasizing the use of patent data to support research innovation.

Management Schools (9%): Three universities provide courses through management schools, aiming to develop talent with expertise in both management and IP.

Course contents

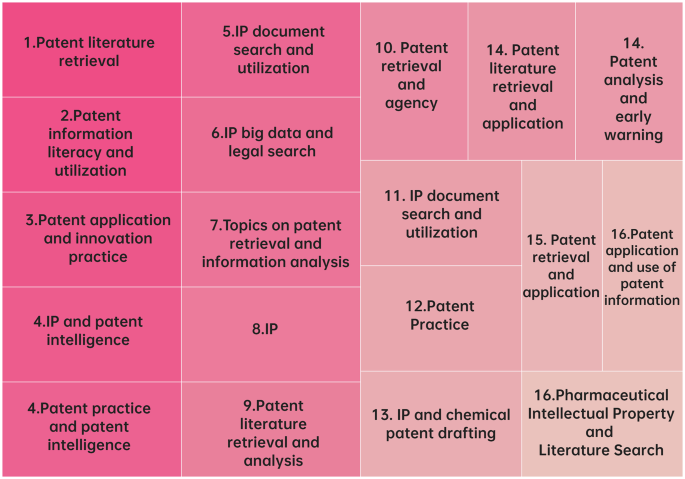

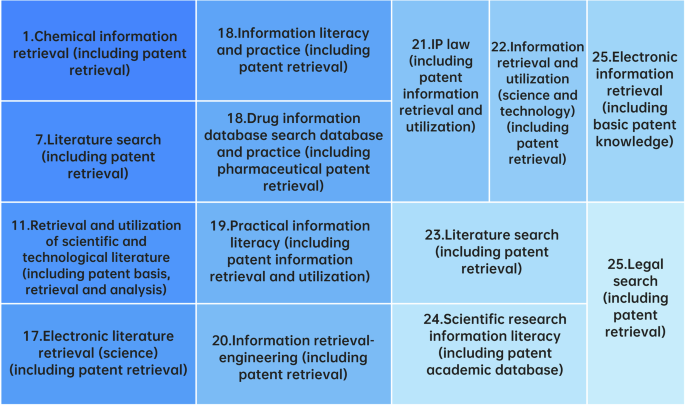

The analysis of the 33 courses indicates that 19 are specialized courses dedicated to IP information literacy, and the remaining 14 are general courses with embedded IP information literacy content, typically allocated limited coverage and class hours (see Figs. 4, 5). As examples of this limited allocation, East China University of Science and Technology includes a chapter on patent retrieval in its course, and Shanghai Jiao Tong University allocates only two hours to patents in a 32-h curriculum.

1. Peking University; 2. Tsinghua University; 3. Beijing Jiaotong University; 4. Tianjin University; 5. Dalian University of Technology; 6. Tongji University; 7. East China University of Science and Technology; 8. Nanjing University; 9. Xiamen University; 10. South China University of Technology; 11. Chongqing University; 12. Xi’an Jiaotong University; 13. Beijing Institute of Technology; 14. Nanjing University of Science and Technology; 15. Hunan University; 16. Wuhan University of Technology.

1. Peking University; 7. East China University of Science and Technology; 11. Chongqing University; 17. Fudan University;18. Shanghai Jiao Tong University; 19. Zhejiang University; 20. Shandong University; 21. Central South University; 22. Sichuan University; 23. Harbin Institute of Technology; 24. Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 25. University of Science and Technology of China.

The content of these courses can be summarized into three main areas:

Basic knowledge: Many courses provide foundational IP knowledge. Examples include “Information Retrieval-Engineering” at Shandong University, “Information Retrieval” at East China University of Science and Technology, and “Information Literacy and Practice” at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

IP information retrieval: Some universities emphasize IP retrieval, particularly patents. For example, Fudan University’s “Electronic Document Retrieval (Science)” teaches patent information access through specialized databases. Peking University’s “Chemical Information Retrieval” focuses on patent databases such as SciFinder and Reaxys. And Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s “Drug Information Database Search” highlights pharmaceutical patent retrieval and analysis.

Analysis of patent information: This advanced topic covers patent retrieval practices, early warning analysis, and report writing. Nanjing University of Science and Technology’s master’s-level course, “Patent Analysis and Early Warning,” expands on the undergraduate course, focusing on practical applications and real-world problem-solving.

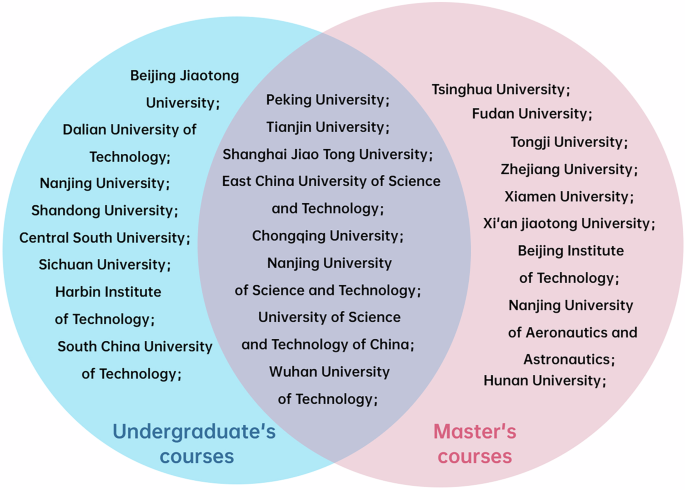

Educational level

Of the 33 courses, 16 are at the undergraduate level and 17 are at the master’s level (see Fig. 6). Eight universities offer undergraduate-only courses, nine offer master’s-level courses only, and eight offer courses at both levels, demonstrating educational continuity. At the undergraduate level, 11 courses are elective, and 5 are compulsory, focusing on foundational knowledge and general education. At the master’s level, 13 courses are elective, and 4 are compulsory, covering advanced patent information and specialized IP information literacy skills.

Universities offering IP information literacy courses at the undergraduate and/or master’s levels.

Practices of IP information literacy education in the libraries of 30 universities

Students’ course selection is influenced by factors such as interest, academic background, and scheduling. Libraries play a critical role in extending classroom learning and fostering the development of IP information skills. This study explores the IP-related practices of the 30 university libraries, including databases, training, lectures, and micro-courses.

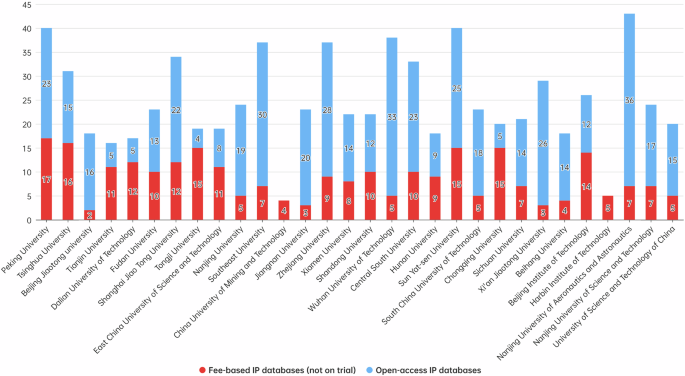

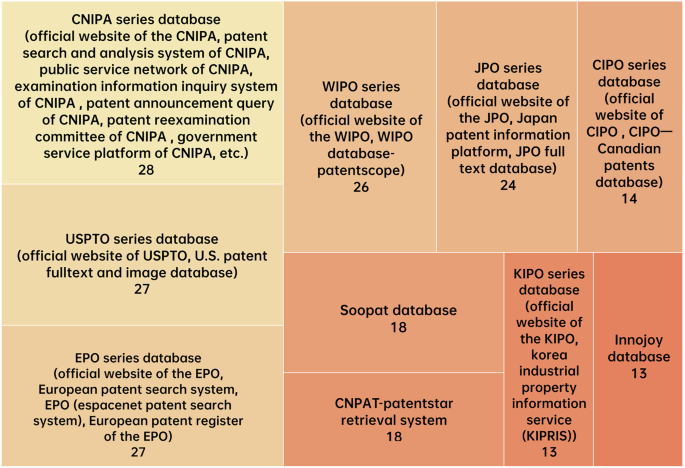

IP databases in libraries

University libraries employ diverse IP database acquisition strategies, integrating both fee-based and open-access resources (see Table 7). This strategic integration fosters a comprehensive information ecosystem for users. Among the 30 universities, libraries maintain a total of 743 databases (mean = 24.77/institution). The distribution of the database shows significant variation (SD = 9.70, RSD = 39%), ranging from 43 (Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics) to 4 (China University of Mining and Technology). Open-access databases are more prevalent than fee-based resources at most institutions, including library-built IP databases (see Fig. 7). The analysis also examines database accessibility pathways, emphasizing their vital role in supporting student self-directed learning.

Distribution of fee-based and open-access IP databases across 30 university libraries.

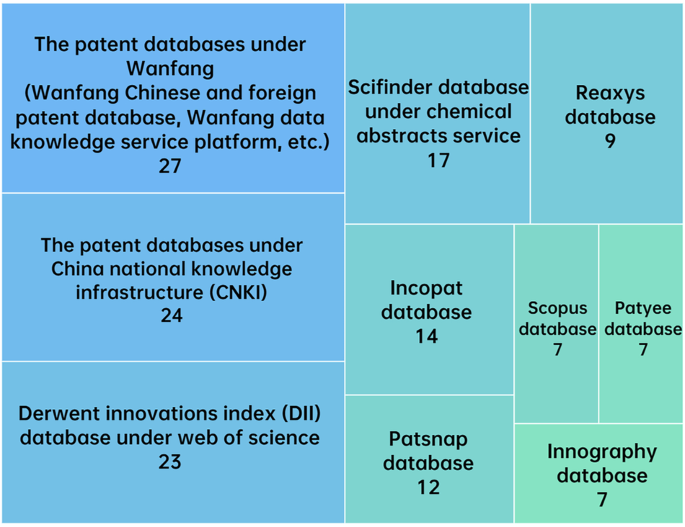

(1) Fee-based IP databases

Of the total 743 databases, 263 (35.4%) are fee-based, with an average of 8.77 per library (SD = 4.32, RSD = 49%). The distribution of fee-based databases varies significantly: 13 libraries maintain 10 or more, 12 have between 5 and 9, and 5 have between 2 and 4. Peking University leads with 17 fee-based databases, while Beijing Jiaotong University has the fewest, with only two.

The top 10 most subscribed fee-based IP databases demonstrate a “concentration at the top, dispersion at the tail” pattern, with the highest subscription rates found in major platforms such as Wanfang, CNKI, and Web of Science (see Fig. 8). Among these, six are patent-integrated platforms (ranking 1st–3rd and 9th for comprehensive academic coverage; 4th and 7th for chemical sciences), providing integrated access to patents, papers, and reports. These widely-subscribed IP databases meet universities’ needs for efficiency and cost-effectiveness. The remaining four databases (ranked 5th, 6th, 8th, and 10th) are specialized patent databases, reflecting the specific research and teaching requirements of universities.

Note: The numbers represent university library subscriptions.

(2) Open-access IP databases

With budget constraints limiting the acquisition of fee-based databases, open-access databases serve as a crucial alternative, accounting for 64.6% (n = 480) of all IP databases. These include resources from national IP offices, international organizations, free tiers of commercial databases, and library-built databases. By linking these databases to their websites, libraries offer students convenient access. Twenty-eight libraries integrated these resources, with 22 (81%) providing 10 or more open-access databases (SD = 4.32, RSD = 27%). The moderate variation suggests libraries’ efforts to promote equitable access while controlling costs. Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics leads by providing 36 databases, while China University of Mining and Technology and Harbin Institute of Technology have yet to implement this initiative.

An analysis of the top ten open-access databases (see Fig. 9) reveals seven public platforms and three free tiers of Chinese commercial databases, with adoption rates ranging from 28 to 13 libraries. This distribution reflects both the public service mandate and international reach of these databases, while demonstrating the predominance of domestic resources.

Note: The numbers represent university library provisions.

(3) Library-built IP databases

Four libraries have developed institutional IP databases, demonstrating innovative approaches to the development of high-quality, specialized resources. These databases can be categorized into two types:

Internal resource integration: Tongji University’s Institutional Repository and Shandong University’s IP Public Service Platform exemplify this model, systematically aggregating institutional IP resources, including patents, research outputs, and papers, to enhance resource discoverability and facilitate disciplinary knowledge transfer.

External resource aggregation: Wuhan University of Technology’s “Free Academic Resources” platform synthesizes global patent databases and academic content. And Beijing Institute of Technology’s Strategic Emerging Technology Patent Database focuses on patents, policies, and reports related to strategic industries.

Both types of databases serve as models for resource development that promote internationalization, specialization, and diversification.

(4) IP database access pathways

Twenty-seven libraries designate “patents” as a resource category within their Database Navigation sections to facilitate student access. However, 26 libraries exhibit inconsistent and illogical access pathways, featuring multiple entry points that lead to varied results and necessitate navigation through 4 to 5 website levels. For example, Peking University’s access pathway follows “Homepage → Library Research Services → IP Services → Patent Resource Navigation.” Southeast University requires the path: “Research Services → Research Support → IP Services → IP Information Service Center → Resource Navigation,” along with an inefficient “Resource Search” option for accessing IP databases. Chongqing University’s website shows varying database availability: two IP databases under “Patents,” 15 databases through keyword searches, and five additional open-access databases via its IP Information Service Center.

IP information literacy training, lectures, and micro-courses in libraries

Libraries offer short training, lectures, and online micro-courses (including microvideos and microtexts/images) as flexible alternatives to formal coursework, providing students with autonomy and reducing the pressure of examinations. These offerings, delivered online or offline, reflect libraries’ efforts to accommodate diverse learning preferences and enhance accessibility.

Libraries adopt various terms for IP literacy education, such as “IP Information Literacy Education” (Dalian University of Technology), “IP Service” (Peking University, Chongqing University), and “IP Information Service” (Nanjing University). Some libraries embed IP information resources within broader categories, such as “Learning Support” (Tsinghua University), “Information Literacy Teaching” (Fudan University Library), and “Information Literacy” (Tongji University), requiring users to navigate subcategories, which can complicate resource discovery.

(1) Offline training and lectures

Libraries primarily offer specialized IP information training and lectures, often supplemented by embedded instructions.

These sessions cover topics such as IP basics, information retrieval/analysis, and advanced issues. For example, Zhejiang University Library’s “Patent Salon” (2022) covered patent fundamentals and applications. Tongji University’s “Information Literacy One-hour Lecture Series” addressed the role of patent information in research innovation and technical problem solving. These expert-led sessions integrate real-world cases and database applications. Libraries at Shandong University and Beihang University also offer customized training based on student requests. Some libraries, such as Beihang and Fudan, embed IP information literacy content directly into course curricula.

(2) Online training, lectures and micro-courses

Online resources offer greater accessibility and flexibility through two primary channels: library-produced content (micro-courses, recorded or live online training and lectures) and the China IP Distance Education Platform of the CNIPA, from which some libraries utilize resources to operate their own substations.

An analysis of library websites and WeChat accounts (see Table 6) reveals that all libraries provide online IP training and lectures, primarily through livestreams, with replays available for some sessions. Ten libraries operate platform substations, and 21 libraries offer micro-courses. Seven libraries provide all three resources (online training/lectures, platform substations, and micro-courses), whereas four offer only online training and lectures.

Characteristics of IP information literacy education at 30 universities

IP information literacy education has garnered significant attention

This study indicates that IP information literacy education is generally emphasized at these universities and is progressing well. Among the 30 universities, 25 (83%) offer formal courses on IP information literacy. These courses exhibit variations in type, credit weighting, class hours, content, educational level, and the secondary units responsible for their delivery.

Libraries at the 30 universities serve as key providers of IP information literacy education beyond the formal curriculum, notably through facilitating access to IP databases. This highlights the universities’ determination and investment in advancing IP information literacy. In addition to fee-based IP resources, many universities optimize the use of online resources to provide free open-access databases, aiming for the best cost-efficiency between funding investment and educational outcomes. Moreover, many provide various forms of training, lectures, and micro-courses in both online and offline formats. Some libraries also explicitly establish special sections such as “IP Information Literacy Education” and “IP Information Services” on their official websites, facilitating students in searching for and accessing IP information resources.

University IP information literacy education centers primarily on patents

Another characteristic of this study is that IP information literacy education at the 30 universities is predominantly centered on patents. The majority of courses offered are patent-centric, encompassing basic patent knowledge, patent retrieval, and patent analysis. This emphasis extends to educational content and resources provided by the libraries.

Challenges in IP information literacy education at 30 universities

Inadequate accessibility and insufficient systematization

Accessibility and systematization challenges in IP information literacy education prevail across most universities. Among the 30 universities, five do not offer any IP information courses. Most courses are elective and often briefly introduce IP information within broader information curricula, which limits the depth and breadth of the content. These nuanced findings have not been previously reported in existing research. Elective courses, which carry low credit, combined with students’ limited awareness, result in insufficient learning motivation, as also noted by Fernández-Molina et al. (2022). Furthermore, many universities do not offer courses at both the undergraduate and master’s levels. This limited accessibility, along with the patent-focused content and lack of curriculum diversity, may impede students’ acquisition of essential IP information skills.

Systematic delivery is also lacking in the library’s educational initiatives. The offline training and lectures are irregular, limiting broader student access. Both online training and lectures remain patent-focused, while micro-courses provide only fragmented content, thus hindering systematic learning.

Inter-library IP resource disparities and widespread internal access pathway disorganization

Our analysis reveals significant IP resource disparities among libraries, primarily stemming from varying institutional investment and IP education priorities. The gap is particularly evident in fee-based databases, which offer superior functionality compared to basic open-access alternatives. Notably, two libraries lack even open-access IP databases, in stark contrast to well-resourced institutions like Peking University and Southeast University. While the distribution of learning resources shows less variation, significant differences exist in the establishment of substations for the China IP Distance Education Platform. Most libraries face disorganized IP database access paths, which impede students’ efficient use of resources and reduce their motivation to engage, resulting in wasteful resource investment.

Such resource inequality and disorganized access paths threaten to widen gaps in IP education quality, innovation, and research capabilities. This divide is particularly stark between well-resourced and budget-constrained universities, as well as between universities with varying IP database organizational capacities.

Recommendations

Tailoring major-specific IP information literacy courses

IP knowledge benefits students across diverse majors and professions, including business and marketing, engineering, arts and design, and life sciences (USIPA, 2022). Therefore, IP information literacy education should extend beyond law and STEM disciplines, becoming a fundamental component of comprehensive education across academic domains.

Given that students are central participants in education (Feng, 2006), universities must tailor IP information literacy programs to meet the specific needs of different majors and educational levels. Courses should adopt a broader, interdisciplinary approach that goes beyond patents. For example, business and management students should focus on trademark and geographical indication information retrieval and use. Students in creative arts and media disciplines should prioritize copyright information literacy. Electronic engineering, computer science, and semiconductor students need to emphasize information of integrated circuit layout design. Students in agriculture and life sciences should focus on information of plant variety rights. This major-specific approach ensures students acquire IP information knowledge directly relevant to their fields.

Developing a systematic and coherent course framework

Our findings reveal gaps in the implementation of IP information literacy education across universities. We propose a framework based on Bruner’s (2009) spiral curriculum theory, which emphasizes progressive learning through repeated exposure to key concepts. This approach has been validated across disciplines (Coelho and Moles, 2016; Trevor and Kenneth, 2007). This framework, spanning both undergraduate and master’s levels across various majors, should incorporate compulsory, embedded, and practical courses, including internships, to enhance systematic and coherent IP information literacy education.

For undergraduates, we propose a compulsory general course, with a minimum of 16 class hours, for all lower-year students. This course should cover both IP information basics and search skills. For students in fields such as LIS, management, law, and IP, a specialized compulsory course of at least 32 h should be offered to meet their advanced needs. To prevent fragmentation and loss of knowledge among upper-year undergraduates, we recommend a second phase of in-depth learning through embedded instruction. This approach, validated by Tang and Pan (2010), involves librarians or IP experts delivering targeted content within regular classes, with each session lasting 1–2 h.

For master’s students, especially those in IP-intensive fields, more advanced instruction is needed, including complex IP information search, evaluation, risk assessment, and report writing. For senior master’s students, we suggest practical courses or internships in collaboration with IP offices, regulatory bodies, companies, or courts to enhance their practical skills. For master’s students in other fields, IP information literacy education can be integrated into specific research projects, with experts teaching relevant aspects of technology, artistic works, or commercial products. Alternatively, collaborations between companies, libraries, and academic departments could provide focused training on IP information retrieval, utilization, and creation. With sufficient resources, these practical opportunities could also be extended to undergraduates.

Enhancing library IP information resources and access

IP databases are essential educational resources in libraries. The scope and accessibility of these databases directly impact the quality of IP information literacy education. However, limited financial and human resources often prevent libraries from independently establishing comprehensive IP information education systems (Ran and Ma, 2023). We propose cost-effective strategies to bolster library IP databases: expanding free open-access database offerings, developing internal IP information collections, selectively subscribing to commercial databases based on user feedback, and promoting inter-library database cooperation and sharing. These measures will create a cost-efficient, comprehensive, and accessible IP information ecosystem, address resource disparities, and support student learning beyond the classroom. To enrich online resources, libraries should record more of their offline training and lectures for online access, establish a substation within the China IP Distance Education Platform, and develop additional micro-courses.

Furthermore, optimizing access pathways to IP databases on library websites is also important. The variability in nomenclature and categorization of IP information literacy resources across universities highlights a potential area for standardization. A more uniform approach would simplify access for students and encourage greater engagement with these valuable resources. We recommend refining the website design, including the creation of a comprehensive IP information resource directory under a dedicated “Intellectual Property” navigation category. Ensuring consistency in search results across different access paths will help users discover all relevant resources. Additionally, implementing smarter search functions and providing clear database usage instructions will prevent students from missing essential resources due to unfamiliarity with database names or content.

Discussion and conclusion

Our comprehensive analysis of IP information literacy education at 30 Chinese National IP Demonstration Universities reveals a mixed landscape, with both progress and persistent challenges.

Universities have increasingly recognized the importance of IP information literacy education, leading to a diversification of courses and library initiatives. The increasingly favorable external policy and economic conditions at the macro level are likely direct incentives (Du et al., 2022). Libraries play a pivotal role in this area, a finding consistent with several studies (Ma et al., 2024; Munyoro et al., 2023). Some Chinese university libraries demonstrate a particularly strong commitment, investing more in patent databases than their US counterparts (Cui, 2021) and providing a variety of online and offline learning resources (Li and Liu, 2022).

In terms of educational content, the 30 universities place particular emphasis on patent information. Library educational practices similarly favor patents, a point corroborated by the research findings of multiple scholars (Liao and Zhou, 2022; Liu and Yu, 2021). Researchers highlight that patent information education is particularly important for science, engineering, and life sciences majors (Cui, 2011; He, 2022; Macmillan and Thuna, 2010; Wang and Zhao, 2017). This preference stems from patents’ rich repository of technical, design, historical, legal, and commercial information (Zwicky, 2019), which is crucial for scientific and technological innovation, market strategy, and policy-making (Wang et al. 2015). We posit that this trend aligns with China’s strategic shift from a manufacturing-based economy to an innovation-driven economy.

However, this preference has resulted in a narrow scope of educational content, limiting its coverage of the broader spectrum of IP information. As discussed in the literature review, the scope of IP extends far beyond patents to include trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets, integrated circuit layout-design rights, geographical indications, and plant variety rights. Each of these subfields has its own unique characteristics and value, warranting thorough attention in IP literacy education. However, these areas have not received the attention they deserve. For example, Beihang University, despite its renowned expertise in integrated circuits, does not offer even basic IP information literacy courses, much less specialized courses on integrated circuit layout-design rights information literacy. This restricted focus and resultant homogeneity in educational content may significantly impact students in business and management, creative arts, electrical engineering and computer science, agriculture and life sciences, potentially hindering their ability to address future IP information challenges. Several scholars advocate for major-specific IP information literacy education to address these diverse needs (Bingöl, 2017; Sun, 2015; Wang, 2020; Zhang, 2024).

Libraries vary significantly in their provisions of IP databases and learning resources. Many face challenges in access pathway organization, which also has been documented in a recent study (Ma et al., 2024). Liao and Zhou (2022) broadly grouped public platforms (e.g., national IP/patent offices) and fee-based databases together as a single indicator of libraries’ basic functionality. However, the two types differ substantially in terms of functionality and content. Such conflation risks generating distorted assessments of library resource adequacy. Our data confirm significant distributional disparities between open-access and fee-based databases across universities.

Limitations in course types, content, and levels, combined with fragmented library resources, underscore systemic deficiencies in IP information literacy education. These findings align with previous research (Xu and Yuan, 2023; Zhang and Bao, 2022). For many students, IP information literacy education remains an optional, peripheral part of their studies. As a result, they are unable to fully utilize available resources and receive adequate education. In particular, students from disciplines less related to patents may face difficulties in effectively addressing complex IP challenges.

Our findings emphasize the critical necessity of adopting a more comprehensive strategy. We propose developing courses tailored to the diverse needs of students across various majors and creating a coherent course framework that integrates IP information literacy education at different educational levels, thus broadening its reach. This approach aligns with recommendations from scholars who advocate for mandatory courses related to IP information (Dimitrova et al., 2020; Trencheva et al., 2018). Furthermore, enhancing university library resources and optimizing access to them are essential measures to improve the overall quality and accessibility of IP information literacy education.

In conclusion, this study highlights the urgency of strengthening IP information literacy education in Chinese higher education institutions. This endeavor is essential for fostering a future generation of professionals equipped with the IP information awareness, competencies, and innovative capabilities necessary to meet the demands of the information age.

Limitations and future studies

This study presents three key limitations in interpreting its findings:

First, our sampling focused on the 30 National IP Demonstration Universities, which limits the generalizability of our findings, as these institutions are leaders in IP information literacy education. Given that China is home to over 3,000 higher education institutions, our results may not fully capture the experiences of non-demonstration universities, particularly those at different developmental stages.

Second, our data collection methodology, primarily relying on institutional websites and supplementary email surveys, has inherent limitations. Valuable educational practices may go undocumented if they are not publicly available, and the comprehensiveness of website content varies across institutions. Additionally, email survey responses were influenced by participants’ differing interpretations of IP information courses.

Third, the study lacks stakeholder perspectives and an impact assessment. We did not interview faculty members, librarians, or students to understand their views on IP information literacy education. These limitations precluded a comprehensive evaluation of both the impact on student competency development and the challenges faced by educational implementers. The absence of these insights restricts our understanding of the practical effectiveness of this education.

Given these limitations, future research should extend beyond demonstration universities, employ diverse data collection methods, and gather stakeholder insights to assess program effectiveness and student outcomes.

Responses