Interbrain neural correlates of self and other integration in joint statistical learning

Introduction

In real-world environments, individuals are able to automatically and implicitly extract meaningful units from dynamic sequences, such as identifying different syllables in language1,2,3. This specific ability, known as statistical learning, has been repeatedly observed in the literature using a variety of stimulus sequences, including but not limited to word segmentation4, actions5, and abstract shapes6. More importantly, task relevance is reported to be a prerequisite for statistical learning to occur, whereas task-irrelevant information is treated as noise and is automatically filtered out by the participants’ visual system during statistical learning7. For example, when presented with an interleaved stimulus stream consisting of two different colored sequences of three elements (i.e., triplets), participants exhibit significant statistical learning effect only for the triplets required to respond7. Until recently, research on statistical learning has focused primarily on individual contexts8,9,10; it remains unknown whether individuals can form mutual statistical representations between themselves and their partners even when their partners’ task information is irrelevant. In real life, mutual statistical representations between individuals are frequently necessary across numerous different social scenarios, which we refer to as joint statistical learning11,12,13. For example, children often acquire language and social competencies from others through play. Indeed, a recent study in our own lab has shown that individuals are able to spontaneously represent the statistical regularities associated with their partners’ tasks in a joint action setup14. Specifically, when co-actors sit together and practice their own serial reaction time tasks (SRTTs) embedded in fixed sequences, they exhibit a significant learning effect on their own sequences as well as their partners’ sequences14.

While the mechanisms underlying joint statistical learning are not well understood, the formation of mutual statistical representations between individuals inevitably involves real-time information integration perceived by one’s self and by others15, a process known as self-other integration16. Previous neuroimaging studies on collective music-making and interpersonal movement coordination have suggested that people can integrate information from one’s self and from others while synchronizing with external stimuli presented in phase synchronicity (e.g., drumming task, finger tapping task), which has been termed interpersonal entrainment17,18,19. These self–other integrations depend largely on using external events (e.g., tempo) as perceptual cues for both actors to achieve self-other integration at the perceptual-action level. More importantly, the strength of self–other integration can be diminished by decreasing the interpersonal entrainment exerted by the external cues (e.g., asynchronous metronome beats), which disrupts the mutual representations of actions between actors20,21. Given the implicit nature of a statistical learning task, it is essential to investigate whether self–other integration is inherently correlated with the formation of mutual statistical representation, and whether this is done without explicit synchronizing cues. Specifically, similar to external interpersonal entrainment, the presence or absence of statistical regularity should also regulate the levels of self–other integration.

Furthermore, we aimed to investigate the multi-brain mechanism underlying the self-other integration during the joint statistical learning. Although increased movement synchrony in dyads has been widely used to indicate strong self-other integration and implies that there should be a neural counterpart to movement synchrony, current neuroimaging studies have primarily focused on investigating the neural correlates of self-other integration at the individual level only17,20,22. However, this individual-level approach can only reveal changes in individual neural activity related to self-other integration, and is unable to explore real-time information integration between dyads in social contexts. These limitations can be better addressed by studying brain-to-brain coupling (BtBC, i.e., the neural systems of two brains that are temporarily coupled) using hyperscanning techniques (i.e., simultaneous recording from multiple brains), which aims to capture interbrain synchrony and can provide an excellent ecological framework for studying the neurodynamics of information transfer and integration between individuals13,23,24,25. Among various hyperscanning approaches, hyperscanning with EEG allows us to capture the unfolding of time-locked inter-brain neural responses with superior temporal precision26,27,28. Previous EEG hyperscanning literature has reported that the BtBC is present in a wide range of EEG frequencies depending on the nature of the joint tasks (for a review, see ref. 29). For higher beta and gamma frequency bands, BtBCs are typically found during motor coordination tasks30 and intention reading31 respectively. On the other hand, lower alpha band BtBC is frequently observed in shared attention tasks32 as well as interactive decision-making tasks33, while BtBC in the theta band is mostly observed in joint action tasks (e.g., two actors pressing the buttons simultaneously28,34 and/or alternately35).

Taken together, the goal of the current study was threefold. First, we wanted to investigate whether participants could acquire statistical regularity through self-other integration when each participant responded to only half of a fixed stimulus sequence. In individual contexts, the traditional view holds that task relevance is a prerequisite for the occurrence of statistical learning7. However, in joint contexts, as reported in previous joint action literature, the irrelevant co-actor’s stimuli might become salient, thereby breaking the filter of task relevance and allowing the stimuli to be represented by the actors14,36. Indeed, our recent research has demonstrated that people can spontaneously represent the statistical regularities embedded in their co-actors’ tasks14. Thus, we expected both participants in a dyad to exhibit a statistical learning effect through representing and integrating task information from both the self and the other. As a result, each co-actor would exhibit similar reductions in reaction time (RT), P3 activity, and functional connectivity between the frontal and parietal regions within the theta band along with the learning process, as reported in previous individual-level statistical learning studies37,38,39. These aforementioned reductions have been suggested to reflect the anticipatory effect40,41,42 and a reduction in top-down stimulus processing38,43,44 due to the acquisition of statistical regularities. Second, we aimed to investigate whether the BtBC serves as a key neural correlate underlying the dynamics of self-other integration in joint statistical learning. Considering that BtBC is particularly able to reflect successful information transfer between individuals45,46,47, we expected that an enhancement of BtBC during the acquisition of statistical regularities would predict better statistical regularity learning (i.e., a steeper slope of RT decreasing along with the learning process). Third, we examined whether the presence of statistical regularity (i.e., fixed sequences) or absence of statistical regularity (i.e., interference sequences) would regulate the strength of self-other integration. Here, the joint statistical learning effect (i.e., statistical learning effect in a joint statistical learning setup) is used to index self-other integration as the extent of self-other integration is typically indexed by the joint action effect (i.e., joint Simon effect) in previous literature16,48. We expected that decreased self-other integration and diminished BtBC would be observed when statistical regularity went from being present to becoming absent. This prediction is supported by evidence that self-other integration relies heavily on the extent to which our motor control system is able to predict our own as well as other’s actions in joint action setups48,49,50. For example, elevated self-other integration was reported when partners’ actions became more predictable in joint Simon tasks48. Accordingly, when the upcoming target is highly predictable (i.e., the presence of statistical regularity), participants are more likely to integrate its information into their own cognitive representations regardless of who’s turns.

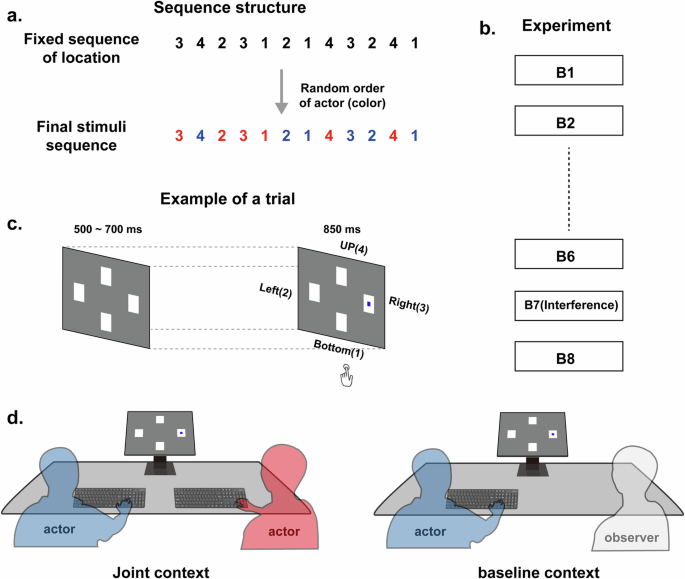

To examine the aforementioned goals, we employed a complementary statistical learning task, in which a modified SRTT paradigm was used to implicitly induce the self-other integration process in a joint action setup. Specifically, a fixed sequence of stimuli was randomly divided and then assigned to each co-actor for responses (Fig. 1a). The experiment consisted of a learning phase, in which a fixed stimulus sequence was repeatedly presented, and a modulating phase, in which an interference sequence was inserted and then followed by the original fixed sequence (Fig. 1b). During the experiment, recruited participants were randomly paired and then required to perform the tasks in either the joint context or the baseline context (Fig. 1d). In the joint context, two participants sat side by side and performed the complementary task together. In the baseline context, an actor and an observer sat side-by-side with only the actor was required to perform the task. Both dyad members’ RTs were recorded to examine the statistical learning effect. Meanwhile, their EEG activities were recorded concurrently to quantify the intra-brain (Event-Related Potentials, ERPs) and functional connectivity in either self-relevant trials (self-responding) or self-irrelevant trials (partner-responding), as well as the underlying multi-brain mechanisms.

a Stimulus structure used, with target locations following a fixed sequential order length of 12. The fixed target sequence maintained an equal number of red and blue dot targets (i.e., six red dot targets and six blue dot targets), but the color order in the sequence was randomized. b The experiment comprised eight blocks. Blocks 1 to 6 and 8 were constructed from a fixed sequence of locations, while the seventh block was constructed from an interference sequence of locations. c Temporal organization of the trials. d Schematic representation of the experimental procedure. The human figures represent the participants. In the joint context, two actors sat side-by-side and performed the complementary task jointly, responding to their pre-assigned targets (e.g., participants sitting on the left responded to the blue dot targets). In the baseline context, one actor and one observer sat side-by-side. Only the actors were required to perform their pre-assigned targets, while the observers simply observed the screen without responding.

Results

The experimental results of both behavior and EEG data were summarized in both the learning phase (Block 1 to 6) and the modulating phase (Block 6, 7, and 8). In the learning phase, the learning effect was quantified using slopes of both RT and EEG activity changing from Block 1 to Block 6. In the modulating phase, the changing trends of both RTs and EEG data from Block 6 to Block 8 were inspected. Both the interference effect (i.e. the difference between Block 6 and Block 7) and the recovery effect (i.e. the difference between Block 7 and Block 8) were further examined after significant quadratic trends were revealed. The following ERP and intra-brain functional connectivity results were derived exclusively from the analysis of the actors’ data in both the joint and baseline contexts. Specifically, the EEG data (including P3, intra-brain functional connectivity, and brain-to-brain coupling) were time-locked to the onset of the target stimulus. BtBC results, on the other hand, were based on the analysis of both dyad members in both the joint and baseline contexts.

Behaviour Data

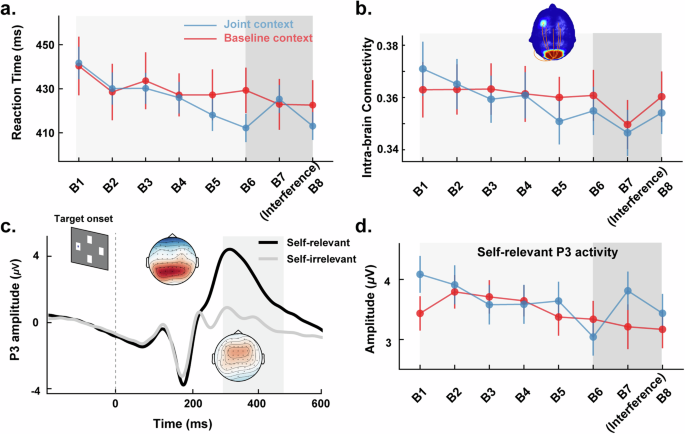

The results of RTs revealed neither a significant main effect of learning phase (β = −1.87, SE = 1.05, t418 = −1.79, P = 0.075) nor a significant main effect of context (β = 7.58, SE = 13.11, t80 = −0.58, P = 0.565). However, the two-way interaction effects in learning phase × context were significant (β = −3.50, SE = 1.28, t418 = −2.73, P = 0.007). This interaction demonstrated that the slope of RTs decreasing from Block 1 to Block 6 was steeper for the joint context compared to the baseline context (see Fig. 2a). These results indicate that, in comparison to the baseline context, the joint context exhibited a facilitation effect on sequence learning.

a Reaction times (RTs) reported by block for the joint context (blue) and baseline context (red). The light grey shading represents the learning phase, while the dark grey sharding represents the modulating phase. The error bar represents the Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). b Intra-brain connectivity activity in the theta (3 to 7 Hz) band reported by block for the averaged trials. The head diagram shows the significant interaction pairings of channels. The orange lines represent statistically significant coupling pairs between the corresponding areas. The head color reflects the number of pairs. The error bar represents the Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). c Grand-averaged ERP waveforms at the parietal region showing peak amplitudes for the P3 components for self-relevant (Black) and self-irrelevant (Grey) trials. Scalp topographic voltage maps for the P3 components were shown near the peak amplitudes. d P3 activity for self-relevant trials reported by block in the joint context and baseline context. The error bar represents the Standard Error of the Mean (SEM).

Furthermore, two models were built to account for the behavioral performances in the modulating phase. The results of the quadratic model revealed a significant main effect of context (β = −68.02, SE = 21.13, t229 = −3.33, P = 0.001), a two-way interaction between context and phase (β = 66.66, SE = 20.37, t164 = 3.27, P = 0.001), and, notably, a two-way interaction between context and phase^2 (β = −15.72, SE = 5.04, t164 = −3.12, P = 0.002). However, the results of the linear model revealed neither a significant main effect nor an interaction (ts < 1.34, Ps > 0.182). Furthermore, model comparison supported the quadratic model (AIC = 2441.3, BIC = 2470), which had a significantly better fit than the linear model (AIC = 2458.2, BIC = 2486.5, χ2 = 18.98, P < 0.001; see Fig. 2a).

For the interference effect, the results revealed neither a significant main effect of phase (β = 6.36, SE = 4.78, t82 = 1.33, P = 0.187) nor a significant main effect of context (β = 2.42, SE = 11.93, t73 = 0.20, P = 0.840). However, the two-way interaction effects in phase × context were significant (β = −19.50, SE = 5.85, t82 = −3.33, P = 0.001). A follow-up simple effect analysis showed that the RTs was significantly larger in Block 7 (M = 425 ms, SE = 6.95) than in Block 6 (M = 412 ms, SE = 6.95) for the joint context (β = 13.14, SE = 3.38, t = 3.89, P < 0.001), but that there were no significant differences in RTs observed between Block 6 (M = 429 ms, SE = 9.70) and Block 7 (M = 423 ms, SE = 9.70) in the baseline context (β = −6.36, SE = 4.78, t = −1.33, P = 0.187).

For the recovery effect, the results revealed neither a significant main effect of phase (β = −0.34, SE = 4.79, t82 = −0.07, P = 0.944) nor a significant main effect of context (β = 2.42, SE = 12.03, t73 = 0.20, P = 0.841). However, the two-way interaction effects of phase × context were significant (β = −11.94, SE = 5.87, t82 = −2.04, P = 0.045). The follow-up simple effect analysis showed that the RTs was significantly larger in Block 7 (M = 425 ms, SE = 6.95) than in Block 8 (M = 413 ms, SE = 6.95) for the joint context (β = 12.28, SE = 3.39, t = 3.63, P < 0.001), but no significant differences in RTs were observed between Block 7 (M = 423 ms, SE = 9.83) and Block 8 (M = 423 ms, SE = 9.83) in the baseline context (β = 0.34, SE = 4.79, t = 0.07, P = 0.944). Altogether, these results demonstrate an enhanced statistical learning effect in the joint context arising from the facilitative influence of acquiring the underlying statistical regularities.

P3

The trial type similarity analysis on P3 revealed a significant main effect of trial type (β = −2.95, SE = 0.33, t82 = −8.95, P < 0.001, see Fig. 2c), with self-relevant trials exhibiting a significantly higher P3 amplitude than self-irrelevant trials. However, there were no significant main effects of context (β = 0.18, SE = 0.38, t120 = 0.48, p = 0.631) nor interactions between trial type and context (β = −0.57, SE = 0.40, t82 = −1.40, P = 0.164). These findings suggest that participants had distinct neural activity between trial types, and therefore the subsequent analyses were conducted separately.

Regarding self-relevant trials (see Fig. 2d), the analysis of the learning phase on P3 amplitude revealed neither a significant main effect of phase (β = −0.06, SE = 0.04, t418 = −1.44, P = 0.151) nor a significant main effect of context (β = 0.48, SE = 0.50, t95 = 0.96, P = .341). However, the two-way interaction effects of phase × context were significant (β = −0.11, SE = 0.05, t418 = −2.01, P = 0.045). This was indicated by the slope of the P3 amplitude decreasing from Block 1 to Block 6 being steeper in the joint context compared to the baseline context. Furthermore, the results of the quadratic model revealed a significant main effect of context (β = −33.62, SE = 12.22, t164 = −2.75, P = .007), the two-way interaction between context and phase (β = 9.50, SE = 3.52, t164 = 2.69, P = .008), and, notably, the two-way interaction between context and phase^2 (β = −0.66, SE = 0.25, t164 = −2.62, P = 0.010). However, the results of the linear model revealed neither a significant main effect nor an interaction effect (ts < 1.88, Ps > 0.062). Furthermore, the model comparison results revealed that the quadratic model (AIC = 900.9, BIC = 932.6) exhibit a significantly better fit compared to the linear model (AIC = 912.2, BIC = 936.9, χ2 = 15.30, P < 0.001) for the modulating phase data.

For the interference effect in the self-relevant trials, the results revealed neither a significant main effect of phase (β =−0.17, SE = 0.26, t82 = −0.68, P = 0.499) nor a significant main effect of context (β = −0.31, SE = 0.52, t82 = −0.60, P = 0.552). However, the two-way interaction effects of phase × context were significant (β = 0.94, SE = 0.31, t82 = 3.01, P = 0.004). The follow-up simple effect analysis showed that the P3 amplitude was significantly larger in the Block 7 (M = 3.81, SE = 0.31) than in Block 6 (M = 3.04, SE = 031) for the joint context (β = 0.77, SE = 0.18, t = 4.25, P < 0.001), but no significant differences in P3 amplitude were observed between Block 6 (M = 3.35, SE = 0.41) and Block 7 (M = 3.18, SE = 0.41) in the baseline context (β = 0.17, SE = 0.26, t = 0.68, P = 0.499). However, there were no significant main effects nor interaction effects seen for the recovery effect in the self-relevant trials (ts < −1.37, Ps > 0.173).

For self-irrelevant trials, there were no significant learning effects (ts < 1.90, P > 0.058) or modulating effects (ts < 1.18, Ps > 0.240 for the linear model; ts < 0.88, Ps > 0.381 for the quadratic model) on the P3 amplitude. These findings indicate that neural activity during sequence learning, as indexed by P3, exhibits enhanced dynamics specifically for self-relevant regularities in the joint context.

Intra-brain Functional Connectivity (FC)

For the theta band, since the FC results revealed neither a main effect of trial type nor of the two-way interaction of trial type and context (ts < 1.33, Ps > 0.186), a series of LMMs were performed for all electrode pairings using the averaged Phase-Locking Values (PLV)s. The results revealed significant main effects of the phase (9 channel combinations, all PFDR < 0.05) and phase × context interactions (7 channel combinations, all PFDR < 0.05). The channel combinations of significant interaction predominantly located between the frontal and parietal regions and revealed that the slopes of the intra-brain PLV decreasing from Block 1 to Block 6 were steeper in the joint context as compared to the baseline context (β = −2.85 × 10-3, SE = 1.30 × 10-3, t418 = −2.19, P = 0.029; see Fig. 2b). However, the results revealed only a significant effect of phase^2 (β = 0.01, SE = 0.01, t164 = 2.16, P = 0.032) and of phase (β = −0.15, SE = 0.07, t164 = −2.16, P = 0.032) during the modulating phase. We did not observe other significant effects during the modulating phase (ts < 0.14, Ps > 0.887 for the linear model; ts < 0.46, P > 0.637 for the quadratic model).

BtBC data

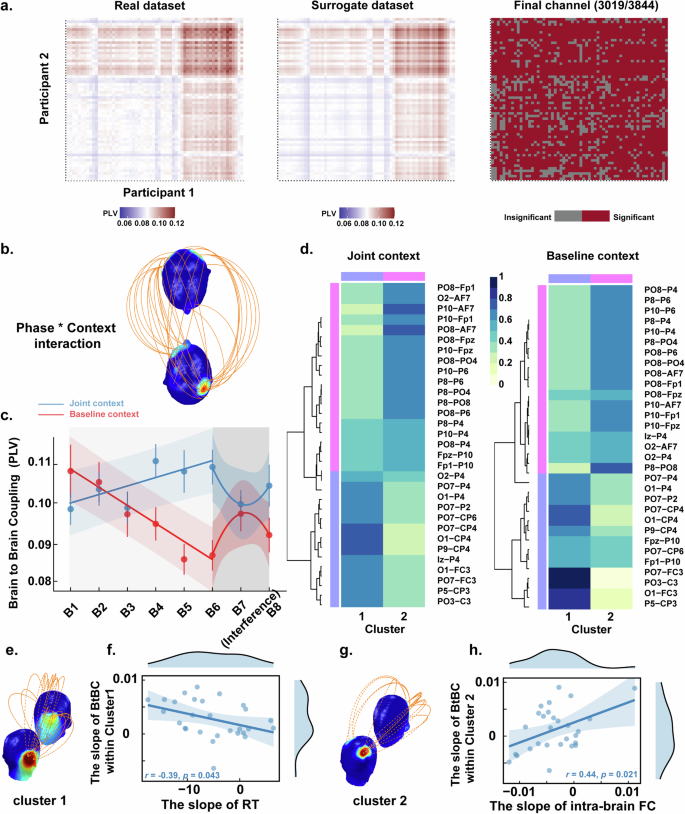

In the first step, a total of 3019 channel combinations were identified where the PLV significantly exceeded the averaged surrogate PLVs in the theta band (all PFDR < 0.05). Subsequently, in the second step, a series of LMMs were conducted on the channel combinations that remained after the first step (see Fig. 3a).

a Comparisons between real data and surrogate data used to filter out channels showed no significant effects. Only significant channels with significant results were retained for subsequent analyses. b BtBC analyses revealed a series of Phase × Context interactions. The head color indicates the number of BtBC over a region normalized to the total number of significant BtBC. c Mean BtBC for channel combinations showing significant interactions reported by block for the joint context (blue) and the baseline context (red). The error bar represents the Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). d Heatmaps of non-negative matrix factorization for the join and baseline context. The dendrograms in the heatmap illustrate the organization of the clusters generated by hierarchical clustering. e The pattern of BtBC in Cluster 1. f The increasing trend in BtBC (i.e., the more positive slope) as represented by the NMF-derived Cluster 1 predicted the decreasing trend in RT (i.e., the more negative slope) in the joint context. g The pattern of BtBC in Cluster 2. h The increasing trend in BtBC (i.e., the more positive slope) as represented by the NMF-derived Cluster 2 predicted the increasing trend in intra-brain functional connectivity (i.e., more positive slope) in the joint context.

For the theta band, analysis results revealed significant main effects of phase and, notably, their interactions in 31 channel combinations (see Fig. 3b), all PFDR < 0.05. Further analysis on the channel combinations showed interaction effects demonstrated by the slope of BtBC increasing from Block 1 to Block 6 being steeper in the joint context as compared to the baseline context (phase × context: β = −6.69×10-3, SE = 9.14 × 10-4, t278 = −7.31, P < 0.001). We then investigated the impact of statistical regularities on self–other integrations based on the aforementioned identified electrode pairings (see Fig. 3c). The results of the quadratic model revealed a significant main effect of context (β = 0.73, SE = 0.21, t108 = 3.43, P = 0.001), the two-way interaction between context and phase (β = −0.20, SE = 0.06, t108 = 3.30, P = 0.001) and, notably, the two-way interaction between context and phase^2 (β = 0.01, SE = 0.01, t108 = 3.23, P = 0.002). However, the results of the linear model revealed a significant main effect of context (β = 0.04, SE = 0.02, t125 = 2.32, P = 0.022). Furthermore, the model comparison results revealed that the quadratic model (AIC = −860.5, BIC = −835.5) exhibited a significantly better fit compared to linear model (AIC = −-854.2, BIC = −835.4, χ2 = 10.36, P = 0.006) for the modulating phase data.

Corroborating with previous analysis, we also performed two LMMs for interference and recovery effects on BtBC results. For the interference effect, where the statistical regularity shifted from presence to absence, the LMM included context (i.e., Joint vs. Baseline) and phase (Block 6 vs. Block 7) as fixed effects, along with their interaction. The results revealed a main effect of phase (β = 0.01, SE = 0.003, t54 = 2.93, P = 0.005), a significant main effect of context (β = 0.13, SE = 0.03, t57 = 4.24, P < .001), and notably, two-way interaction effects of phase × context (β = −0.02, SE = 0.01, t54 = −3.92, P < 0.001). The follow-up simple effect analysis showed that the PLV values were significantly larger in Block 6 (M = 0.109, SE = 0.004) than in Block 7 (M = 0.100, SE = 0.004) for the joint context (β = 0.01, SE = 0.003, t = 2.62, P = 0.011), but the PLV values were significantly smaller in Block 6 (M = 0.087, SE = 0.004) than in Block 7 (M = 0.097, SE = 0.004) for the baseline context (β = −0.01, SE = 0.003, t = −2.93, P = 0.005). However, there were no significant main effects or interaction effects for the recovery effect (ts < −1.82, Ps > 0.074).

Clustered BtBC data

To further elucidate the significance of electrode pair interactions within the theta band, we conducted a Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) analysis for each context. Following previous studies51, the smallest value of rank was chosen when the cophenetic correlation coefficient began to decrease (rank = 2 in the present study, see Supplementary Fig. 3). As a result, the two-cluster solutions were obtained for both joint and baseline contexts (see Fig. 3d). Finally, significant correlations between BtBC clusters and individual behavioural and EEG data were observed only for the joint context. Specifically, the slope of BtBC within NMF-derived Cluster 1 (see Fig. 3e) was negatively correlated with the slope of RT (r = −0.39, P = 0.043; see Fig. 3f), indicating that the increasing trend in BtBC (i.e., a more positive slope) within Cluster 1 predicted the decreasing trend in RT (i.e., a more negative slope). Meanwhile, the slope of BtBC within NMF-derived Cluster 2 (see Fig. 3g) was positively correlated with the slope of intra-brain functional connectivity (r = 0.44, P = 0.021; see Fig. 3h), indicating that the increasing trend in BtBC (i.e., the more positive slope) within Cluster 2 predicted the increasing trend in intra-brain functional connectivity (i.e., the more positive slope).

Discussion

The current study utilized a multi-brain EEG methodology to elucidate the inter-brain neural correlates of self–other integration within a joint statistical learning paradigm. Our findings demonstrate that participants exhibited a significant statistical learning effect in the joint context relative to the baseline context, as indexed by the RT measurements. Specifically, greater reductions in RT were observed during the learning phase in the joint context compared to the baseline context. Also, RTs showed a quadratic trend by increasing and then decreasing along with the absence or presence of statistical regularities, respectively. Corroborating the RT reductions, for self-relevant trials only, we observed significantly more reductions of neural responses (e.g., P3 components and theta-band functional connectivity) in the joint context compared to the baseline context during the learning process. Furthermore, P3 activity exhibited a similar quadratic trend to that observed in RT measurements. At the inter-brain level, there was a significant increase in BtBC during the learning phase, which was then modulated by the absence or presence of regularity in the theta band in the joint context compared to the baseline context. Further cluster analysis also revealed that the slope of BtBC was negatively correlated with the slope of RT and positively correlated with the slope of intra-brain functional connectivity during the learning phase in the joint context. Taken together, these findings indicate that BtBC is a crucial neural correlate of self–other integration, which underlies the observed joint statistical learning effect.

In line with our predictions, significant reductions in RT when responding with a co-actor revealed that participants are able to assimilate task information from both themselves and their co-actors14,15,52, thereby extracting statistical regularities from ongoing complementary inputs. More importantly, a significant quadratic trend in RT was exhibited along with the presence or absence of statistical regularity, providing further causal evidence regarding joint statistical learning. In addition to the findings regarding behavioral performance, intra-brain level analysis provided further evidence about the occurrence of a joint statistical learning effect. First, we found a similar functional network as reported in previous research findings, located between the frontal and parietal regions within the theta band, and which correlates with top-down processes such as goal-directed control and attentional shifting38,39,43,44. Crucially, the observed strength reductions of this functional network suggest a decline in top-down stimulus processing as a result of learning statistical rules, and then a shift toward a greater reliance on bottom-up processes when new information is presented38,39,43,44. Second, decreased target onset-locked P3 (also observed in target offset-locked P2, please see Supplementary Results and Supplementary Fig. 1) during the learning phase, suggesting a predictive process accompanying the statistical learning53,54. This aligns with the anticipatory effects documented in prior electrophysiological and eye-tracking statistical learning research40,41,42,55. Interestingly, the pre-stimulus anticipation effect was unaffected by the presence or absence of statistical regularity, suggesting that the participants tended to predict future stimuli for as long as they acquired statistical regularity. However, when the incoming stimulus was inconsistent with their prediction, participants exhibited a surprise-related activity indexed by the enhanced P3 amplitude during the interference block. It is also worth noting that, unlike in previous studies56,57, we did not find similar neural activity for both the stimuli perceived by the self and for that perceived by participants’ partners in ERPs, but instead it was seen in intra-brain functional connectivity. We speculate that this may be due to the fact that tasks presented in previous studies may have involved only a low-level response selection task, where individuals needed only to represent their co-actors’ task information by exhibiting a comparable ERP response. However, in the current study, the task required a rather specialized statistical learning-related frontal–parietal network to comparably process the stimuli experienced by both the self and their co-actor, and then extract the embedded statistical regularity.

The aforementioned behavioral and intra-brain level results extend the statistical learning findings from individual contexts to joint contexts and suggest that individuals can spontaneously represent and integrate their co-actors’ task information, including statistical regularities. Together with the findings from previous studies14,15, these findings are consistent with the rationale of the co-representation account. From a co-representation perspective, people act in such a way that “actions at another person’s command are represented just as if they were at one’s own command”58. Thus, participants may implicitly perform the task of their co-actor and represent their task information accordingly, even when a response is not required. Consequently, the information from both the self-task and other-task in a co-representation context may be coupled and/or integrated, resulting in the observed joint statistical learning effect. More importantly, successfully acquiring statistical regularity through co-representing co-actor’s task as evidenced in the present study as well as in our previous research14, challenges the traditional view that task relevance is a prerequisite for the occurrence of statistical learning7. Specifically in the joint context, as pointed out in previous joint action literature15,59, co-representation might have rendered the irrelevant co-actor’s stimuli salient, thereby breaking the filtration that usually exists during the statistical learning process at the individual level.

Our BtBC findings provide direct evidence for the occurrence of self–other integration. The majority of the existing self–other integration research has primarily utilized single-brain neural markers, and has usually neglected the exploration of dependencies among neural activities in a dyad17,20,22. In contrast, using recently developed hyperscanning methodology, the BtBC analysis in the present study first assessed the dynamic interaction between the two brains, and was able to measure the real-time information transfer and integration between dyads. As predicted, the results showed that the two actors’ brains became more synchronized in theta band over the course of the learning phases in the joint context, even when each dyad member responded alternately. Combined with our findings of the behavioural learning effect, this finding suggests that the two brains become more connected as self-other integration increases60. Thus, increased BtBC could serve as a potential neural correlate for the self–other integration process in joint statistical learning tasks. Again, a similar significant quadratic trend in BtBC was observed along with the presence or absence of statistical regularity, reinforcing the fundamental role of BtBC underlying the self–other integration. In contrast to other repeatedly reported increased BtBC in contexts with external synchronizing cues and/or intentional coordination requirements, such as interpersonal cooperation61, interpersonal entrainment62, and interpersonal observational learning63, the theta band BtBC found in the present study adds to the hyperscanning literature by demonstrating that implicit regularity learning could also drive the self-other integration and induce the associated brain-to-brain coupling.

Furthermore, the clustered BtBC analysis within the theta band revealed two distinct cluster patterns and their functional significances. First, the slope of BtBC within Cluster 1 (i.e., the connection between the parietal–occipital and frontal regions) was negatively correlated with the slope of RT during the learning phase in the joint context, suggesting that this BtBC network is critically related to the process of joint statistical learning. Furthermore, this theta interbrain synchrony within Cluster 1 may be driven by underlying regularity information extracted at the individual level and then serves as a transitive channel in the process of brain-to-brain entrainment64,65. Indeed, for both their own and their partner’s stimulus sequences, participants in the joint context exhibited a significant functional connectivity network (i.e., frontal– parietal regions within the theta band) related to regularity information extraction and encoding as in previous literature38,39,43. However, the aforementioned individual-level efforts alone may not be sufficient to capture the full regularity embedded in the sequences, which required further self-other integration via brain-to-brain communication. For this purpose, theta band interbrain synchrony may act to form a common ground for statistical information transfer given that regularity information is extracted and encoded through a theta band intra-brain network at individual level. Second, the slope of BtBC within Cluster 2 (i.e., parietal–parietal) was positively correlated with the slope of intra-brain functional connectivity during the learning phase in the joint context. Given that the parietal region is fundamental for the attentional processing of external visuospatial stimuli43, it is plausible that the observed inter-brain synchrony between the dyad’s parietal regions is driven by shared attention. Previous studies have indicated that shared attention creates a kind of “perceptual common ground” in joint action, constructing similar realities for each of the two actors and exhibiting increased neural synchronization66,67. Meanwhile, intra-brain functional connectivity has also been shown to be related to attentional control networks during statistical learning at an individual level43. Thus, the positive correlation between the slope of BtBC within Cluster 2 (i.e., parietal-parietal) and the slope of functional connectivity within the brain in this study might indicate that shared attention between dyads drives the attentional control network in both co-actors, which is an essential prerequisite for self–other integration. Indeed, intra-brain connectivity analysis did reveal equivalent activation of low-frequency brain networks in both co-actors in our study, regardless of whether they were participating in the self or the self-and-other trial context.

Finally, the dynamics of self–other integration were shown to be modulated both spontaneously and implicitly by the absence or presence of statistical regularities in the joint context. In the absence of statistical regularities, RT increased as BtBC decreased. In contrast, in the presence of statistical regularities, RT decreased as BtBC increased. While historical perspectives on self–other integration have been rooted in external interpersonal entrainment, a recently developed predictive model of social interaction has suggested that states of interpersonal coordination are shaped by predictive processes that are either exogenously driven (i.e., perceived incoming information) or endogenously derived (i.e., internally produced inferences)68. Exogenous predictions have frequently manifested as interpersonal synchrony seen in mechanisms such as sensorimotor synchronization and in-phase relationships17,69,70. However, little research has thus far explored endogenous predictions. Our findings demonstrate that self–other information can be integrated as a statistical representation through perceptual inference, even in the absence of discernible physical cues or timing, to train sensorimotor coordination. This integrated statistical representation can only be accomplished through the execution of psychological predictions, and providing direct evidence of endogenously derived predictive processes. This resonates with the findings of existing research which shows that pre-acquired task knowledge can modulate the balance of self–other integration and separation21.

One limitation of the current study is the gender distribution of the participants. Our study specifically recruited only female participants, thus constraining the generalizability of our findings to female–female pairings. Therefore, caution must be exercised when generalizing these results to female–male or male–male pairings, especially given that previous research has indicated that gender can influence interpersonal neural synchrony in pairings71. Future research should investigate self–other integration in joint statistical learning contexts among both men and women.

Nonetheless, our research reveals new insights regarding the neural underpinnings of self–other integration during joint statistical learning. Utilizing a concurrent EEG imaging technique, we captured the neural dynamics occurring between participant pairs during the acquisition of statistical regularities. Our findings highlight the unique role of self–other integration in joint statistical learning. In contrast to other research which has examined the neural correlates of statistical learning at an individual level, our study investigated participants’ neurophysiological responses to statistical learning in a more ecologically valid joint setup from an interpersonal neuroscience perspective. We discovered that theta-band phase synchronization across dyads mirrors the process of self–other integration and serves as a predictor for the behavioral learning outcomes. Additionally, our results indicate that self–other integration is inherently connected to the emergence of shared statistical representations, and is modulated by the absence or the presence of statistical regularities.

Methods

Participants

The sample comprised 112 undergraduate students from Zhejiang Normal University (M = 19.82, SD = 1.32, all female). The sample size was not statistically predetermined but was set to match previous studies63,72,73,74. All participants were right-handed and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Participants provided their written informed consent (in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki) before testing began, and each participant was paid for their participation. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of Zhejiang Normal University.

Apparatus and Stimuli

Following a previous SRTT (Serial Reaction Time Task) paradigm41,75, four white squares were presented in a diamond formation against a grey background in four spatial locations (i.e., up, down, left, right) on an LCD computer screen of 1680 × 1050 pixel resolution (size 47 × 29 cm). A red or blue dot appearing in the center of a white square represented a target. The squares were each 6 × 6 cm in size (approximately 4.6° × 4.6° of a visual angle), and the dots were 1.5 cm in diameter (approximately 1.4° × 1.4° of a visual angle). The target locations followed a 12-step fixed sequential order, in which location frequency and first-order transition probabilities were counterbalanced. Two such sequences were used: Sequence A: 3-4-2-3-1-2-1-4-3-2-4-1, and Sequence B: 3-4-1-2-4-3-1-4-2-1-3-2 (numbers corresponding to location: 1-down, 2-left, 3-right, 4-up). For each target sequence, the number of red-dot targets and the number of blue-dot targets was kept the same (i.e., six red-dot targets and six blue-dot targets), but the color order in the sequence was randomized (see Fig. 1a). Twelve concatenated sequences constituted one block (144 stimuli). The experiment consisted of eight blocks in total (see Fig. 1b), each starting from a different position within the sequence, specifically the 1st, 5th, 10th, 8th, 4th, 12th, 1st, and 2nd positions for Blocks 1 through to 8, respectively. Blocks 1 to 6, as well as Block 8, were all constructed from a main sequence (e.g., sequence A), while the 7th block was constructed from an interference sequence (e.g., Sequence B). The choices of main or interference sequence was counterbalanced across the dyads. The stimuli were presented using E-Prime 3.0 software. The viewing distance from the monitor was 60 cm. A chin rest was used to help participants maintain their head position during recording.

Procedures

The recruited participants were paired randomly and placed in either the joint context or the baseline context (see Fig. 1d). In the joint context, the two participants sat side-by-side and performed the complementary task jointly, and were required to respond to their pre-assigned targets (e.g., the participant sitting on the left responded to the red-dot targets and the participant sitting on the right responded to the blue-dot targets). In the baseline context, one actor and one observer sat side-by-side, and only the actor was required to respond to their pre-assigned targets while the observer simply observed the screen without responding. Mappings of the target colors and sitting positions of actors in both contexts were counterbalanced across dyads.

In both the joint and baseline contexts, the actors in the dyads were asked to complete the modified SRT task. During this task, a screen with no target was shown for 500 to 700 ms, and acted as a frame to predict the ongoing stimuli (see Fig. 1c). Then, a target appeared in one of the four locations for 850 ms. When the target appeared, the actors were instructed that, when their pre-assigned target (either the red or the blue dot) appeared onscreen, they were to locate them within their range of vision as quickly as possible, and press a corresponding keyboard key. For example, up-arrow or the 8 key indicated the top square, the down arrow or the 5 key indicated the bottom square. The target remained visible onscreen for the whole 850 ms, no matter whether participants responded or not.

The task required participants to first complete 10 practice trials to ensure they understood how to map the visual stimulus locations and provide their manual responses. The whole experimental procedure lasted about 30 min. After each task, participants were asked if they had noticed a sequence or pattern in the task they had just completed. All participants in this study indicated they were unaware that there was a sequence or pattern present.

EEG Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

In both joint and baseline contexts (including the observer), the neural activity of both participants was recorded simultaneously using a dual-EEG recording system with a 64-channel BioSemi ActiveTwo system, and connected to two synchronized amplifiers to guarantee millisecond-range synchrony between the two EEG recordings. The electrodes were positioned according to the extended 10-10 system. Data were recorded continuously at 512 Hz without online filtering, except for the use of a default hardware anti-aliasing filter. Grounding electrodes (CMS and DRL) were placed centrally near POz.

EEG data preprocessing was conducted using EEGLAB and Fieldtrip software76,77. First, a 1 Hz high-pass FIR filter and a 30 Hz low-pass FIR filter were applied. The continuous EEG data were segmented into epochs. Channels with excessive noise were identified and interpolated via spherical interpolation. The data were then re-referenced to the average of the linked T7/T8 electrodes. Blinks and eye-movements were identified and removed using Independent Components Analysis (ICA) run in EEGLAB. Epochs exceeding ± 80 μV were excluded from further analysis. On average, 0.45% of the total data (SD = 1.36%) in total of 1152 trials was removed because of excessive noise for each participant.

Data analysis

The following Analyses were conducted to examine both behavior and EEG data. The experiment consisted of two main phases: a learning phase (Blocks 1 to 6) and a modulating phase (Block 6, 7, and 8). Within the modulating phase, the data were further examined based on the absence or presence of statistical regularities. Specifically, two main components were analyzed: the interference effect (the difference between Block 6 and Block 7) and the recovery effect (the difference between Block 7 and Block 8).

Due to the interdependence between dyads, following procedures used in previous studies15,63, LMM was utilized for the statistical analyses. For the learning effect, the data were modeled with phase (i.e., Blocks 1 to 6) as a within-subject predictor, context (i.e., Joint vs. Baseline context) as a between-subject predictor, and their interaction as fixed effects. Random effects were included to account for variability between participants and dyads (that is, variation between the participants nested within each dyad). Significant interaction effects were further explored using simple slope analyses.

To confirm that the task regularities modulated performances, we fit both linear and quadratic models to the modulating phase data (i.e., Blocks 6, 7, and 8). Model fit was compared using a chi-square test of deviance to determine whether the linear model or the quadratic model provided a better fit.

The linear model was defined as in Eq. (1):

The quadratic model was defined as Eq. (2):

LMM was conducted using the lme4 package in R78. ANOVAs were used to detect main and interaction effects using the anova function. Significance tests on the parameters used the Satterthwaite P-values from the lmerTest package79. Post-hoc contrasts and simple slope analyses were conducted using the emmeans and interactions packages, respectively.

To avoid potential confounding variables, such as differences in motor response requirements, the individual-level EEG analysis—including ERP and intra-brain functional connectivity measures—was exclusively based on data from the actors (i.e., those required to respond) in both the joint and baseline contexts. In contrast, the BtBC analysis included data from both dyad members in both the joint and the baseline contexts.

Behavioral data analysis

Consistent with the findings of prior research37, Reaction Time (RT) was defined as the time between target onset and the correct key-press response. Trials with incorrect or absent responses were excluded from analysis. On average, 2.32% (SD = 4.17%) of data was excluded for each participant.

ERP analysis

Following the analysis procedures of previous studies, we determined the latency ranges for the ERP components using a data-driven procedure38. This entailed the computation of a grand-averaged ERP, which was collated from all trials and contexts. The resulting waveform was then employed to define latency ranges. In line with previous research, we identified discernible P1, N1, and P3 components, which are time-locked to the moment of target appearance and are located in the parietal–occipital regions at the POz, PO1, PO2, Pz, P1, P2, O1, O2, and Oz electrode sites (see Fig. 2c & Fig. S1a). In addition, previous research has suggested that during SRTTs, participants may exhibit a predictive processing pattern associated with statistical learning. Therefore, in our study, we also identified a significant P2 component, which are time-locked to the moment of target disappearance and are located in the frontal–central regions at the FCz, FC1, FC3, F1, F3, and FZ electrode sites (see Fig. S1b). P3 latency ranges for the mean amplitude were computed over a time window centered on the peak using the aggregate grand average from the trial results. Using this criterion, the latency ranges for the frontal P1, N1, and P3 were 108–153 ms, 183–223 ms, and 300–440 ms, respectively. Mean amplitude for the frontal P2 component was computed over a 220–300 ms time interval. For each participant, the ERP amplitude was averaged over the aforementioned latencies. For the results of target onset-locked P1, N1 and target offset-locked P2, please see Supplementary Results and Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2.

Previous research on joint actions has shown that similar neural activity is observed for both the stimuli belonging to the actors and the stimuli belonging to their partners56. For example, in the joint picture naming task, participants exhibited similar lexical processing related activity (indexed by P300 amplitude) when it was their turns to respond and/or when it was their partners’ turns to respond. This suggests that representing both self-relevant and self-irrelevant task information is the premise of self–other integration. Therefore, ERP analysis included two steps. First, we examined whether there were similar or equivalent ERPs of self-relevant and self-irrelevant trials in both joint and baseline contexts (i.e., trial type similarity analysis). Second, we further examined the representative learning effect in ERPs associated with each trial type at the individual level.

Intra-brain Functional Connectivity (FC) analysis

Guided by prior research demonstrating that statistical learning in the parietal–occipital cortex is synchronized with frontal activity39,43, and reinforced by our previous ERP results localizing statistical learning effects to the POz electrode, we calculated pairwise connectivities between the POz seed and all other electrodes. Connectivity was quantified using the Phase-Locking Value (PLV) which ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater synchronization between signals. Calculation of the PLV requires extraction of the instantaneous phase at the target frequency for each signal77. The PLV was calculated as in Eq. (3):

where N represents the number of trials, T represents the number of time points, φ is the phase, || represents the complex modulus, and i and j indicate the channel i and channel j in the participant, respectively. Phase was extracted from signals using the Hilbert transform. Prior to connectivity analysis, the data were filtered into three frequency bands of interest: theta (3-7 Hz), alpha (7-12 Hz), and beta (12-20 Hz) using finite impulse response filtering. Based on the main ERP periods, connectivity was examined in the 100-500 ms time window following target onset.

Consistent with the ERP analysis, we first examined trial type for similarity between each of the oscillatory bands, and then performed a series of LMMs for all electrode pairings. For the results of alpha and beta bands, please see Supplementary Results and Supplementary Fig. 2.

BtBC analysis

we next examined whether shared neural responses between dyad members could reflect self–other integration and predict learning outcomes. To measure the potential inter-brain synchronization between the EEG signals of the two interacting dyads in the joint and baseline contexts, we used PLV, similar to in intra-brain functional connectivity and previous hyperscanning studies31,72,80.

In terms of statistical analysis, a major criticism of studies on BtBC concerns the lack of control for spurious synchronization due to sharing a common task context81. To address this issue, previous studies propose a statistical approach, in which real BtBC due to meaningful interactions is compared to pseudo-BtBC due to common visual inputs and/or environmental factors and the former is expected to be significantly higher63,80. Specifically, we generated 200 surrogate time series for each electrode pair by randomly shuffling the trial order. We then computed the PLV for each surrogate series and averaged these values at the subject level, obtaining 200 averaged surrogate PLVs. The phase-locking statistic (PLS) was defined as the proportion of averaged surrogate PLVs exceeding the original PLV. Significant synchrony between a region pair existed only if the PLS was below 0.05 after False Discovery Rate correction (FDR correction; ref. 82). Regions of interest (ROIs) for further analysis were restricted to pairs showing significant synchrony in either the joint or baseline context within specific time periods and frequency bands. Additional comparisons of inter-brain synchronization were performed based solely on synchronization within these ROIs. Furthermore, we used a custom script (dualheadnetplot.m) in MATLAB to visualize the BtBC interaction effect83.

Clustered BtBC Analysis

Next, brain synchronization patterns associated with significant interactions from the above analyses were clustered for the joint and baseline contexts separately using non-negative matrix factorization (NMF; refs. 23,63). To achieve stable results, NMF was run 1,000 times. The number of clusters was determined as being the first value at which the cophenetic coefficient started to decrease, following the “Brunet” version of NMF51. The relationship between clustered brain synchronization and learning measures was tested using Pearson correlation analysis.

Responses