Intercontinental movement of exotic fungi on decorative wood used in aquatic and terrestrial aquariums

Introduction

The introduction of microorganisms and insects into new areas where they are not native has resulted in devastating losses from many invasive pathogens and pests. This intercontinental movement has been responsible for the loss of billions of trees in the United States alone1. Diseases such as Dutch elm disease, white pine bister rust, chestnut blight, sudden oak death, laurel wilt, and many others were caused by introductions that have not only killed massive numbers of woody plants in the urban and forest landscapes but also resulted in extreme ecological damage1,2,3,4,5. These past introductions occurred from the transport of soil, timber, wood products, living trees, or other plant material. Although some of the most damaging invasive pathogens were introduced into the United States over 100 years ago and efforts to prevent these introductions from occurring were put into effect, these efforts have not always been successful6,7. New avenues for exotic fungi to be introduced continue to be realized8. This is a problem not only for the United States but for many countries worldwide as new plant diseases continue to be introduced4,9,10. Recently nonendemic fungal pathogens of plants and people were found on imported wooden handicrafts8. These authors suggest that fungal pathogens are of particular concern and pose a very high risk due to their rapid emergence, low resistance in host populations, and limited surveillance infrastructure for detection.

Importation of materials and microorganisms from Asia has been responsible for many introductions in the past. New studies have shown that many of the introduced Phytophthora species have likely originated in Asia11,12. In addition to these highly virulent known pathogens, many undescribed species have been found in that region. It has been suggested that these little-known species could also become destructive diseases if given the opportunity to move into areas where they are not native13. Many have a wide host range and could undergo jumps to new hosts after importation. Eco-evolutionary dynamics of fungi suggest that trees or other plants that have not evolved with the pathogen would have little to no resistance to these fungi or fungal-like organisms10.

Recently, an unusual fungus was found colonizing wood used for decoration in aquatic aquariums14. Xylaria apoda, a fungus not previously reported in the United States and native to Asia, was found growing underwater on wood in aquariums located in Minnesota and Colorado. The wood had been imported from Asia and was purchased from pet stores. Although the various woods had been dried, shipped and stored for a long period of time, the fungus remained viable and grew throughout the submerged wood producing fruiting bodies. Finding the same exotic fungus in wood from aquariums located in two different states within the United States raises serious concerns that this wood, widely used throughout the world for decorative purposes in aquariums, could be harboring other exotic microorganisms including potential plant pathogens. Several different types of wood, such as wood classified as spiderwood and driftwood, are sold by vendors from Asia online and also in pet stores. Spiderwood has unusual shapes with multiple branches and galls and driftwood consists often of degraded tropical woods from coastal areas or from the forest floor that contain interesting patterns with holes and crevices that are attractive decorations in fish tanks (Figs. 1 and 2). This study was done to determine what fungi and Oomycota are being transported alive in imported decorative aquarium woods and to identify pure cultures of fungi obtained after arrival in the United States by DNA sequencing. The introduced fungi were also evaluated to determine if any of them have potential to be pathogenic or cause detrimental effects when introduced into new ecosystems.

Results

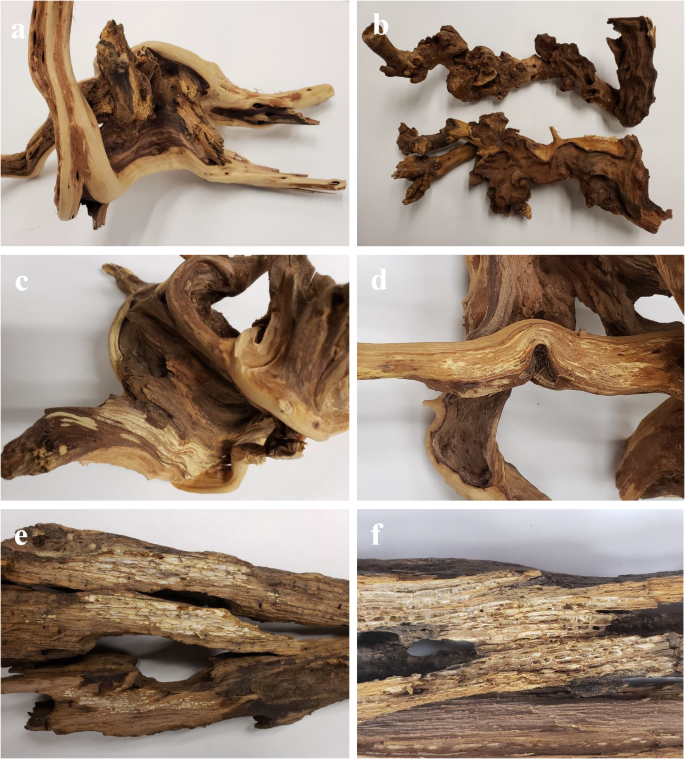

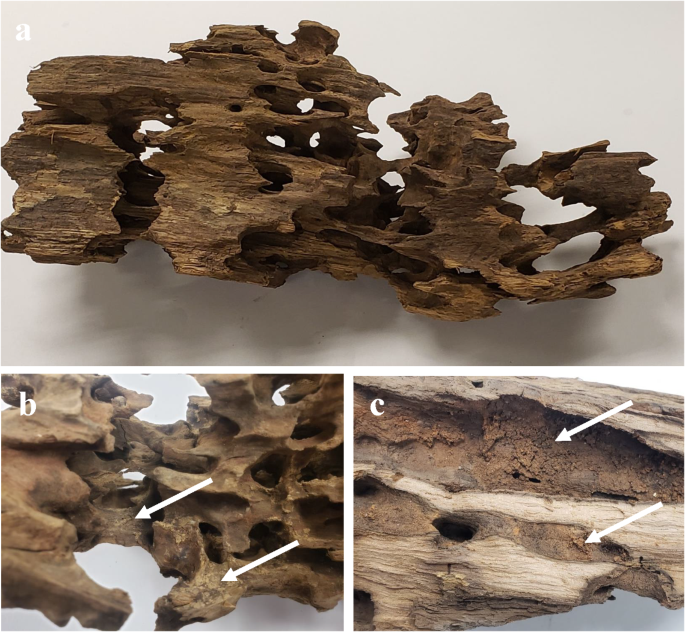

Forty-four samples of decorative wood used for aquariums that originated from Asia were found to visually appear to have varying amounts of discolored and decayed zones. Some samples had pseudosclerotial plates produced by fungi while others had various stages of white rot, white-pocket rot or other evidence of degradation (Fig. 1). Samples sold as driftwood were extensively degraded and many had large holes present throughout the wood. This wood appeared to be extractive rich tropical hardwoods that had been degraded on the forest floor. When samples were split open for isolation, evidence of mud and sand were present within the voids in some samples (Fig. 2).

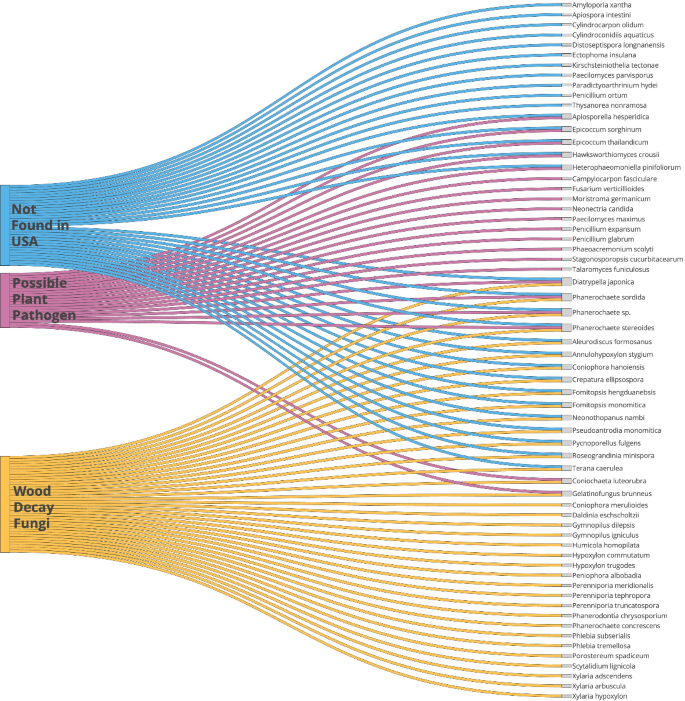

Isolations made from the wood yielded 204 cultures of viable fungi representing 123 taxa (Table 1). Representative taxa in the Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Mucoromycota were found but no fungal-like organisms in the Oomycota were obtained. A large number of fungi appeared to be from Asia and not previously documented in the United States. This included many fungi that are potential plant pathogens and also fungi that cause wood decay (Table 1 Fig. 3). In addition, 24 taxa have a low ITS sequence match (97% or less) and may represent new species and or genera. Taxa such as Apiosporella hesperidica, Campylocarpon fasciculare, Diatrypella japonica, Epicoccum sorghinum, Fusarium verticilloides, Phaeoacremonium scolyti, Paecilomyces maximus, Talaromyces funiculosus, and others are known pathogens of agricultural crops and trees. Other fungi may have potential to be plant pathogens such as Hawksworthiomyces sp. and Moristroma germanicum and possible human pathogens Apiospora intestine, Coniochaete hoffmannii and Melbranchea ostraviensis. Fungi causing post-harvest problems of fruits and vegetables were also found. These included several Penicillium species. Two entomopathogens, Cordyceps farinose and Purpureocillium lilacinum were found. A large number of Basidiomycota known to cause brown and white rot in wood were found including the bioluminescent Neonothopanis nambi which was isolated several times. A large representation of Xylariales in the Ascomycota were also found. These fungi cause a soft rot attack of wood. In addition, many other saprophytic taxa were identified such as Aspergillus sp., Cladosporium sp., Penicillium sp., and Trichoderma sp.

Discussion

The introduction of non-native fungal species is a biosecurity threat to our natural resources and can have devastating effects for agriculture, forestry and the environment10. In addition to attacking specific types of trees or other plants causing their death, invasive pathogens can devastate ecosystems1,2,4. This study demonstrates that decorative wood used for aquariums contains large numbers of fungi representing many different taxa including nonnative species, potential plant pathogens, and other fungi that could be detrimental to the environment and economy. In a relatively small sample size of 44 different pieces of imported wood for use in aquariums, 204 cultures of fungi were obtained representing 123 different taxa. From this group of fungi, 30 were not previously reported in the United States. Information on vendor sites selling these woods for aquariums boasts that many hundreds have been sold. Although it is not known how many fungi are viable in all these imported woods, the results reported in this study show that with just 44 different samples, there are very large numbers of diverse viable fungi routinely being imported from Asia to other countries in this wood. Many of these are known plant pathogens. The list of imported fungi found in our study alone (Table 1) is a reason for serious concern about potentially dangerous biosecurity risks, however, this represents a small fraction of these types of wood samples being imported that could be introducing a plethora of foreign fungi.

Some of our most serious introduced diseases to the United States are thought to originate from Asia. This includes chestnut blight, Dutch elm disease, sudden oak death, Port Orford cedar root disease, laurel wilt and others6,12,15,16,17,18. Researchers also indicate that there are many unknown species of fungi and Oomycota in Asia that have the potential to be pathogens13,19. Although we did not isolate any Oomycota species from our samples, the presence of mud and soil inside the holes and crevices of the degraded wood being imported indicates that this could be an avenue for various exotic Phytophthora to enter since they reside in aquatic and wet soil environments. Recommendations to people that purchase wood for aquariums are to repeatedly soak and rinse wood in water before putting the wood into an aquarium. This helps eliminate some of the heartwood extractives from the tropical woods and reduces water discoloration in aquariums and possible toxicity to fish and plants. Disposal of the water from this wood into the environment could easily release Phytophthora and also the fungal species that may be in the wood. Additional sampling and investigation using more selective methods of isolating Phytophthora species with baits and selective culture media is needed to determine if this could be a successful avenue for importing species of plant pathogenic Oomycota species.

The forests in Asia where this wood is being collected appears to be an area that has received little mycological study and is rich in undescribed taxa. Of the 123 different taxa identified in this study, 24 have ITS sequence matches of 97% or less to known fungi. This includes many wood decay fungi. An isolate most closely related to Hawkworthiomyces in the Ophiostomatales, is from a group that has been suggested to all have the capacity to decay wood and likely have an association with sapwood infecting insects20. Since many of the Ophiostomatales are known tree pathogens, this exotic species introduced into the United States should remain suspect until proven otherwise. There also are what appear to be new species of Coniophora and Pycnoporellus which cause brown rot, several new species of Phanerochaete that cause white rot and possibly 2 new species of Scytalidium, a genus that is known to have species that cause soft rot in wood. The best blast match for one of the Phanerochaete species was P. sordida, which can be found in many countries including the United States, but the ITS sequence match to this species was only 94%. With such a low match it was considered a species not previously reported in the United States (Table 1; Fig. 1). This was also the case for Terana caerulea with only a 93% match to most known sequences for this fungus. This Terana is likely a new species and was listed as not present in the United States. The introduction of non-native species of wood decay fungi could impact the wood decay community, biomass degradation, and native wood inhabiting insects with potential to cause adverse effects on ecosystem functioning as demonstrated by the recently introduced fungus, Flavodon ambrosius21,22. Another example of an invasive decay fungus is the brown-rotter, Serpula lacrymans, with a natural range in Asia but it has been moved to other regions of the world where it has found a new niche causing timber decay in houses resulting in enormous economic losses23,24. A recent report has documented the introduction of Xylaria apoda in Minnesota and Colorado and its ability to grow in submerged aquarium wood14. Our study found several different species of Xylaria as well as several other fungi in the Xylariales. All these fungi have the capacity to cause wood decay and produce a soft rot type of degradation. Many of these fungi can survive adverse conditions, grow in woods that have decay resistance, and some soft rot fungi can colonize preservative treated wood25. This group of fungi also contains tree pathogens such as Kretzschmaria deusta that causes a serious root and butt rot of hardwoods and Entoleuca mammata that causes a canker disease of poplar26. These are all reasons we should be concerned about the importation of new species in this group.

The results presented here indicate that current regulations to prevent the importation of non-native fungi on decorative woods used in aquariums are ineffective. In this investigation alone, over 100 different live taxa were cultured and the risk of new exotic invasive species that could become naturalized is significant. New strategies for fumigation and sterilization treatment are needed that will be effective on high density, extractive rich tropical woods to close this pathway of fungal and fungal-like organism introductions. Better phytosanitary regulations on imported wood have been repeatedly suggested8,27 and the results presented here reinforce the need for improved regulations that would prevent new introductions that could have catastrophic effects on our natural resources and ecosystem functioning. A global strategy to combat the introduction of exotic fungi with the potential to become devastating plant and animal diseases has been suggested many times4,10,28. An important way to deal with this problem is to improve biosurveillance on a global scale. The biosurveillance study presented here has revealed a previously unknown avenue where many fungi are being moved between continents. Taking action to stop the importation of these fungi and fungal-like organisms before they become serious problems in their new environment is essential.

Materials and methods

Decorative wood labelled as ‘spiderwood’ and ‘driftwood’ was purchased from online vendors Amazon.com and Temu.com. All the wood received appeared dry and wrapped in plastic. Although the exact location where the wood was collected is not known, the vendors address suggested China, Vietnam, Thailand, and possible other Asian countries. Once received, wood segments were cut from the samples and placed in different types of media including i) Malt extract agar (MEA) with antibiotics (15 g malt extract 15 g agar in 1000 ml distilled water amended with 0.1 g/L streptomycin sulphate added after autoclaving ii) a semi selective media for Basidiomycota (15 g of malt extract, 15 g of agar, 2 g of yeast extract, 0.06 g of Benlomyl with 0.1 g of streptomycin sulfate, and 2 ml of lactic acid added after autoclaving) and iii) PARPH, a Phytophthora selective culture media [950 ml deionized water, 50 ml clarified V8 juice and 15 g of Difco Agar and autoclaved for 30 min and allowed to cool to 50 °C. Then 5 ml of PCNB (pentachloronitrobenzene), 1 ml rifampicin (dissolved in methanol) and 50 mg of hymexazol were added.] These types of culture media were used because of previous success in investigations to obtain diverse fungal taxa from wood29,30,31,32. Plates were incubated at 22 °C and once growth appeared, pure cultures were transferred to additional MEA plates. Isolates of pure cultures were then used for DNA extraction and sequencing. Cultures are stored in the University of Minnesota Forest Pathology culture collection in the Department of Plant Pathology.

Identification of fungal cultures was done by extracting DNA from pure cultures grown on petri plates using a PrepMan™ Ultra sample preparation reagent according to manufactures’ protocol. The internal transcribed spacer gene region (ITS) was amplified using primers ITS1F and ITS433. PCR was carried out in 25 µl reactions which contained ~ 12ng of DNA template, 0.25 µM forward primer, 0.25 µM reverse primer, 2.5 µg/µL BSA, 1X GoTaq® green mastermix and 9 µl nuclease free sterile water. Thermocycler program parameters for amplification were: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 62 °C 45 s (-1 °C /cycle for 10 cycles, and then 52 °C for remaining 25 cycles), and 72 °C for 45 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Amplicons were verified by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel with SYBR green 1 pre-stain and imaged with a Dark Reader DR45 (Clare Chemical Research–Denver, CO). Sanger sequencing was done with PCR primers on an ABI 3730xl DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems–Foster City, CA). Consensus sequences were assembled using Geneious 9.034 and were used with the BLASTn program35 using the megablast option in GenBank. Identification of cultures was based on the highest BLAST match score of a genus-species accession from a taxonomic study. Sequences representative of each taxon obtained were deposited in GenBank and are listed in Table 1. For each of the taxa, the biogeography was assessed using multiple sources, including both Index Fungorum and Mycobank, as well as the U.S. National Fungus Collections Nomenclature Database (https://nt.ars-grin.gov), the National Center for Biotechnology Information life-map tree database (http://lifemap-ncbi.univ-lyon1.fr/), and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF; https://www.gbif.org).

Wood samples sold for aquarium decorative purposes and used for culturing fungi showing evidence of fungal colonization and decay. Dark colored areas of dead wood were present along with lighter colored sapwood (a and b). The older dead wood was the location where many fungi were isolated. White rot was present in many samples (c−f) and fungi produced incipient decay leaving a bleached white appearance (c and d) or zones of advanced decay (e and f). A white pocket rot was evident inside several of the samples that were split open for isolation and culturing (e and f).

Samples sold as driftwood were pieces of tropical woods that had substantial degradation resulting in holes throughout the wood. The holes make the wood attractive for use in aquariums (a). The inner zones of this decayed wood often had residual mud and soil present (b and c).

Selected fungal taxa from isolates that were cultured from wood originating from Asia and sold for decoration in aquariums that are possible plant pathogens, wood decay fungi or have not been documented in the United States. Several taxa are represented in more than one category.

Responses