Intermittent fasting as a treatment for obesity in young people: a scoping review

Introduction

The global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents aged 5–19 surged from 8% in 1990 to 20% in 2022, affecting both genders similarly1. The obesity epidemic impacts both developed and developing countries2. In the US, class I obesity increased from 16% to 21% in youth ages 12 to 19 years of age from 1999 to 2018, while severe obesity (classes II and III) rose from 5% to 8%3. This is concerning as obesity has been linked to comorbidities including type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, and metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease4,5,6. In January 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued new clinical practice guidelines for treating obesity in young people. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines recommend prompt, multifaceted intervention strategies, including intensive health and behavioral lifestyle interventions, obesity pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery6.

Adherence to treatment recommendations is possibly the strongest predictor of weight loss7,8,9,10, and the best strategy for a given individual is the one they are willing and able to practice and sustain. Therefore, there is a critical need to diversify interventions to ensure young people can identify the strategies that work for them based on personal preference, developmental and social stage, and obesity phenotype. Intensive family-based health and behavioral interventions are the cornerstone of pediatric obesity treatment6. However, these interventions can only be effective in improving long-term health outcomes if they are delivered and received as intended. While family-based interventions work for some youth and their families who are able and willing to engage and adhere to all the required treatment recommendations, a meaningful proportion disengage prematurely6,10,11. For many adolescent and emerging adults, a family-based approach that relies on involvement of caregivers may not best fit the needs and new autonomous roles of this age group. Furthermore, modifications in the home food environment and complex behavior changes may not be practical or sustainable during this developmental period6. Developing and testing novel intervention approaches can diversify our treatment toolkit to help a greater segment of young people to achieve their health goals12,13,14,15.

Dietary regimens focusing on when food is consumed, rather than on the quality or quantity of food consumed16,17 have gained popularity in the last decade. Intermittent fasting involves altering the timing and duration of eating and fasting periods18. Common intermittent fasting regimens include the 5:2 diet (eating ad libitum 5 days per week and fasting for two non-consecutive 24-h periods), alternate-day fasting (typically involves alternating a day of eating ad libitum with a fast day), time-restricted eating (fasting for a specified period of time each day), and religious fasting19,20. Intermittent fasting interventions emerged from findings indicating that, while diet quality and exercise are beneficial for health, the timing of eating may independently predict health outcomes and disease risks21. Spreading eating events across the day (i.e., >14 h eating window) and late-night eating have been linked to poor cardiometabolic health in adults17,22,23,24. By contrast, well-timed eating and fasting, such as eating earlier in the day and fasting in the evening and night, has been shown to induce weight loss, enhance insulin sensitivity, improved sleep quality, and decrease inflammation20,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. In adults, time-restricted eating studies indicate that shortening the eating period can lead to a 10-25% reduction in energy consumption, even without intentional caloric restriction25,26,27,28. In addition, cycling between periods of fasting and eating has also been linked to reduced markers related to aging, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular health, neurodegenerative conditions, and cancer33,34,35. Intermittent fasting has also been shown to modulate inflammatory responses and reduce oxidative stress24,28,30,31,32. Given the role of inflammation and oxidative stress in accelerating aging, exploring this effect from an early stage in life is compelling.

Intermittent fasting might be appealing to adolescents and emerging adults in allowing more freedom around food choices and because of its simplicity17,24. Yet, studies of intermittent fasting have mainly focused on adults over the age of 30, and research in youth is still in its early stages36,37. Since 2019, over 50 reviews have summarized the effectiveness of intermittent fasting in adults22,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90, with no comparable published summary among adolescents and emerging adults36,37. This scoping review seeks to address this gap by examining all published intermittent fasting studies involving adolescents and emerging adults, irrespective of whether the intervention was specifically intended for the treatment of obesity. Given the limited research in this age group, our focus extends beyond assessing the efficacy of intermittent fasting for weight loss to include feasibility and adherence. Specific considerations were given to: (1) methodology; (2) intervention parameters including eating timing, duration, and additional components; (3) adherence monitoring; (4) feasibility assessment; (5) primary and secondary outcomes captured; (6) potential iatrogenic effects; and (7) effects on anthropometric, metabolic outcomes, and markers of biological aging. This comprehensive approach aims to inform future trials by highlighting gaps in knowledge and evaluating whether intermittent fasting has been sufficiently studied in terms of feasibility and adherence.

Methods

PRISMA-ScR framework

A PRISMA-ScR scoping review was conducted. Consistent with the PRISMA framework91,92 the following steps were executed: (1) identify the research question by clarifying and linking the purpose and research question; (2) identify relevant studies by balancing feasibility with breadth and comprehensiveness; (3) select studies using an iterative team approach to study selection and data extraction; (4) chart the data incorporating numerical summary and qualitative thematic analysis; and (5) collate, summarize and report the results, including the implications for practice and research.

Identifying the initial research questions

The focus of the review was to investigate intermittent fasting interventions that included adolescent and emerging adults. To ensure that a wide range of relevant studies was captured, the following two-part research question was crafted to guide the search93: In intermittent fasting interventions that include adolescents and emerging adults: 1) What were the intervention parameters, adherence monitoring approaches and fidelity measures employed, and primary and secondary outcomes captured, and 2) What is the reported feasibility and efficacy?

A structured search was applied utilizing the PubMed bibliographic database. The first author (JAB) created the initial PubMed search strategy using a combination of Medical Subject Headings and keywords for intermittent fasting, health effects, and youth. The search was restricted to studies published since 2000, on humans, who are adolescents or young adults, and written in English. Intermittent fasting included time-restricted eating, intermittent energy restriction, and alternate day fasting interventions. Team members (JAB, SJS, and APV) reviewed the strategy and preliminary results to modify and improve the search strategy. With the team’s approval, JAB customized the search using controlled vocabulary and keywords in the database listed above. The search strategy included the following terms: ((“intermittent fasting”[MeSH Terms] OR (“intermittent”[All Fields] AND “fasting”[All Fields]) OR “intermittent fasting”[All Fields] OR (“intermittent fasting”[MeSH Terms] OR (“intermittent”[All Fields] AND “fasting”[All Fields]) OR “intermittent fasting”[All Fields] OR (“time”[All Fields] AND “restricted”[All Fields] AND “eating”[All Fields]) OR “time restricted eating”[All Fields]) OR (“intermittent fasting”[MeSH Terms] OR (“intermittent”[All Fields] AND “fasting”[All Fields]) OR “intermittent fasting”[All Fields] OR (“time”[All Fields] AND “restricted”[All Fields] AND “feeding”[All Fields]) OR “time restricted feeding”[All Fields]) OR ((“alternance”[All Fields] OR “alternances”[All Fields] OR “alternant”[All Fields] OR “alternants”[All Fields] OR “alternate”[All Fields] OR “alternated”[All Fields] OR “alternately”[All Fields] OR “alternates”[All Fields] OR “alternating”[All Fields] OR “alternation”[All Fields] OR “alternations”[All Fields] OR “alternative”[All Fields] OR “alternatively”[All Fields] OR “alternatives”[All Fields]) AND “day”[All Fields] AND (“fasted”[All Fields] OR “fasting”[MeSH Terms] OR “fasting”[All Fields] OR “fastings”[All Fields] OR “fasts”[All Fields])) OR ((“intermittant”[All Fields] OR “intermittence”[All Fields] OR “intermittencies”[All Fields] OR “intermittency”[All Fields] OR “intermittent”[All Fields] OR “intermittently”[All Fields]) AND (“energie”[All Fields] OR “energies”[All Fields] OR “energy”[All Fields]) AND (“restrict”[All Fields] OR “restricted”[All Fields] OR “restricting”[All Fields] OR “restriction”[All Fields] OR “restrictions”[All Fields] OR “restrictive”[All Fields] OR “restrictiveness”[All Fields] OR “restricts”[All Fields]))) AND (“weight s”[All Fields] OR “weighted”[All Fields] OR “weighting”[All Fields] OR “weightings”[All Fields] OR “weights and measures”[MeSH Terms] OR (“weights”[All Fields] AND “measures”[All Fields]) OR “weights and measures”[All Fields] OR “weight”[All Fields] OR “body weight”[MeSH Terms] OR (“body”[All Fields] AND “weight”[All Fields]) OR “body weight”[All Fields] OR “weights”[All Fields] OR (“metabolic”[All Fields] OR “metabolical”[All Fields] OR “metabolically”[All Fields] OR “metabolics”[All Fields] OR “metabolism”[MeSH Terms] OR “metabolism”[All Fields] OR “metabolisms”[All Fields] OR “metabolism”[MeSH Subheading] OR “metabolities”[All Fields] OR “metabolization”[All Fields] OR “metabolize”[All Fields] OR “metabolized”[All Fields] OR “metabolizer”[All Fields] OR “metabolizers”[All Fields] OR “metabolizes”[All Fields] OR “metabolizing”[All Fields]) OR (“metabolic”[All Fields] OR “metabolical”[All Fields] OR “metabolically”[All Fields] OR “metabolics”[All Fields] OR “metabolism”[MeSH Terms] OR “metabolism”[All Fields] OR “metabolisms”[All Fields] OR “metabolism”[MeSH Subheading] OR “metabolities”[All Fields] OR “metabolization”[All Fields] OR “metabolize”[All Fields] OR “metabolized”[All Fields] OR “metabolizer”[All Fields] OR “metabolizers”[All Fields] OR “metabolizes”[All Fields] OR “metabolizing”[All Fields]) OR (“body composition”[MeSH Terms] OR (“body”[All Fields] AND “composition”[All Fields]) OR “body composition”[All Fields]) OR (“aging”[MeSH Terms] OR “aging”[All Fields] OR “ageing”[All Fields]) OR (“inflammation”[MeSH Terms] OR “inflammation”[All Fields] OR “inflammations”[All Fields] OR “inflammation s”[All Fields]) OR (“inflammatories”[All Fields] OR “inflammatory”[All Fields]) OR (“oxidative stress”[MeSH Terms] OR (“oxidative”[All Fields] AND “stress”[All Fields]) OR “oxidative stress”[All Fields])) AND (“adolescent”[MeSH Terms] OR “adolescent”[All Fields] OR “youth”[All Fields] OR “youths”[All Fields] OR “youth s”[All Fields] OR (“young adult”[MeSH Terms] OR (“young”[All Fields] AND “adult”[All Fields]) OR “young adult”[All Fields]) OR (“adolescences”[All Fields] OR “adolescency”[All Fields] OR “adolescent”[MeSH Terms] OR “adolescent”[All Fields] OR “adolescence”[All Fields] OR “adolescents”[All Fields] OR “adolescent s”[All Fields]))) AND ((y_10[Filter]) AND (humans[Filter]) AND (english[Filter]) AND (adolescent[Filter] OR youngadult[Filter])). All resulting citations were exported into a Mendeley library, and duplicates were removed. No additional efforts were conducted to seek out gray literature, including other study registries, websites, or conference proceedings. On November 4, 2024, the search was repeated in the bibliographic database to identify any more recent studies.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were first screened, and then eligible full-text articles were screened by one author (JAB) (title abstracts: n = 241, full-text n = 92). For the initial screening of abstracts, the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles are in English; (2) included participants with age equal to or less than 25 years old; (3) report of a primary or second outcome that relates to a change in weight (body mass index, Body mass index z-score, weight in excess of the 95th percentile, percent weight change), a change in metabolic markers (body composition, glycemic biomarkers, or lipid profiles), or a change in biological aging markers (inflammatory markers and oxidative stress). There was only one exclusion criterion. Studies on Ramadan intermittent fasting were excluded due to its unique cultural and ceremonial context, which entails significant alterations in eating habits, sleep cycles, and often leads to increased consumption of high-sugar and high-fat foods, rendering its effects incomparable to other forms of health-promoting fasting18. No exclusion criteria were applied to sample size or location. To assess the scope of ongoing and unpublished research in this emerging field, we also conducted a search of ClinicalTrials.gov using the following terms: “Intermittent Fasting OR Time Restricted Eating OR Time Restricted Feeding OR Alternate Day Fasting OR Intermittent Energy Restriction OR Time Limited Eating OR Time Limited Feeding” combined with “Adolescent OR Young Adult OR Emerging Adult.” This search yielded 231 studies, with statuses as follows: 112 completed, 58 recruiting, 23 unknown, 14 not yet recruiting, 10 active but not recruiting, and the remainder either enrolling by invitation, suspended, terminated, or withdrawn. During subsequent full-text screening, two independent reviewers ensured the following criteria were met for all retrieved studies: (1) publication included full text and (2) publications were peer-reviewed.

Data charting

Data extraction was completed for eligible articles in relation to the study population, intervention details and study outcomes, using a standardized form, which was based on data extraction forms used in previous scoping reviews by the authors (APV). One reviewer (JAB) developed a data-charting form to determine which variables to extract and charted the data. Then, two reviewers discussed the results, and continuously updated the data-charting form. The data extracted included sample descriptions, methodology, outcome measures, assessments, and results of interventional studies. Next, one extractor reviewed all the articles and formed the table (JAB). An additional team member double-checked the extracted data and helped revise the table (APV). Data tables facilitated analysis. Participant characteristics across trial studies, interventions, measures, and results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

The Synthesis Without Meta-analysis guidelines nine-item checklist was adapted for this scoping review to promote transparency in reporting of the quantitative effects of intermittent fasting in the study cohort of interest94. 1) Studies were grouped for synthesis according to their study design and primary outcome measure. 2) Table 1 was created to highlight the primary and secondary outcomes as described by the authors. Table 2 was designed to emphasize the five primary standardized metrics of interest for this scoping review as it relates to use of an intermittent fasting approach in young people which include: 1) feasibility/acceptability; 2) adherence; 3) weight outcome (for studies that included youth with obesity); 4) metabolic markers; and 5) biological aging markers. 3) Given the heterogeneity in outcome measures captured and reported, no transformational methods were used to synthesize the effects for each outcome to undertake a meta-analysis of effect estimate. Alternatively, the data was utilized to explore the landscape of intermittent fasting in this age cohort and identify approaches that had been utilized to date. 4) The studies are ordered chronologically in descending order in Table 1 and Table 2 by those that included an intermittent fasting intervention for the treatment of obesity presented first as the most aligned with the primary aim of the scoping review. 5) To investigate the heterogeneity of the reported effects, the primary and secondary outcomes of each study were outlined and compared to determine the difference in metrics utilized, in the definitions, and measures assessed to capture the effect of intermittent fasting on various metabolic parameters in this age group. 6) The certainty of evidence was assessed with the criteria of credibility assessment tool. 7) The data are presented in both text and table format with studies ordered chronologically and with those that include cohorts with obesity for which intermittent fasting was used and an obesity treatment ordered first.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was not sought for this review as it relies on already published work. Additionally, this review was not registered in PROSPERO, the international database for systematic reviews in health and social care, due to the fact that scoping reviews do not fulfill the registration requirements (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutpage).

Analytic analysis

For each interventional study on the health effects of intermittent fasting, the following data were abstracted: number of participants, ages of participants, study design, intermittent fasting regimen, additional intervention components, adherence monitoring method, feasibility assessment, primary and secondary outcome measures. To evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of healthcare interventions, a generic, theoretically grounded questionnaire was previously developed around the constructs of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability95. This tool was designed to measure seven specific elements related to feasibility: affective attitude, burden, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, perceived effectiveness, and self-efficacy. This versatile questionnaire can be customized to analyze the acceptability of various healthcare interventions across diverse settings. Studies were evaluated on whether they measured acceptability and feasibility consistent with the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability. The other included studies were analyzed conceptually, without charting of specific data.

Results

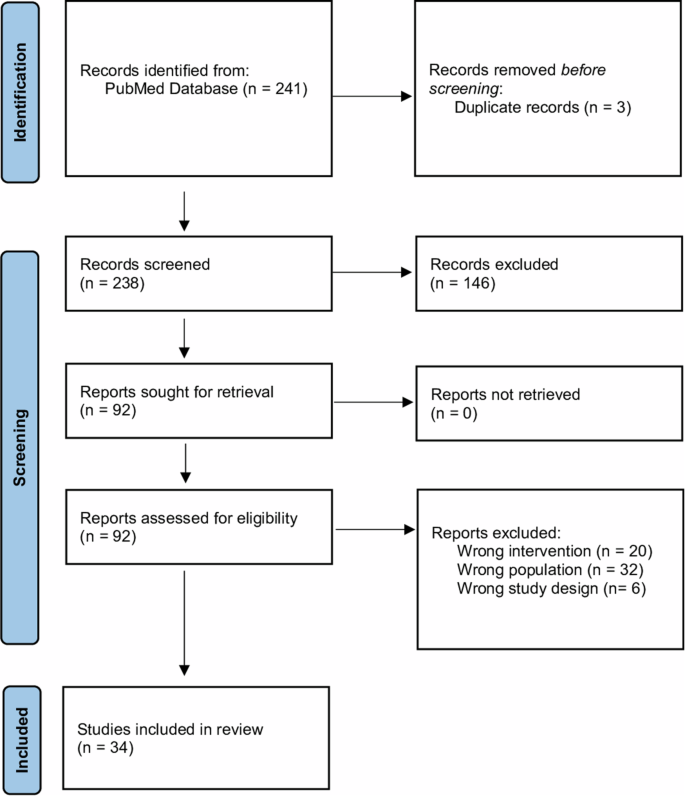

Upon removal of duplicates, 238 titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility. A total of 92 underwent full-text review. Of those, 34 studies met the pre-specified inclusion criteria. A PRISMA flow diagram detailing the database searches, the number of abstracts screened, and the full texts retrieved is illustrated in Fig. 1. The study designs and methodologies of the included studies are cataloged in Fig. 2. Descriptive details of included studies are summarized in Table 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram for new systematic reviews detailing the database searches, the number of abstracts screened, and the full texts retrieved.

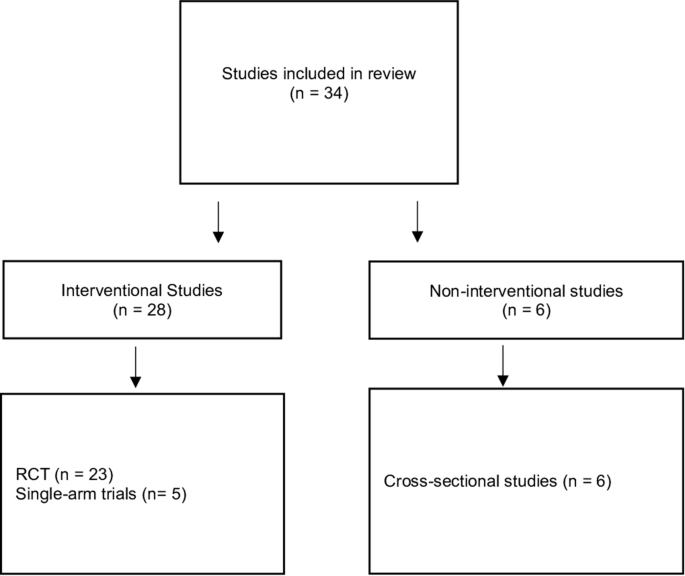

Methodologies of the Included Studies in the Scoping Review.

All studies were published between 2013 and 2024. Twelve studies were conducted in the United States, four in China, three in the United Kingdom, three in Australia, two in South Korea, two in Brazil, one in Italy, one in France, one in Canada, one in Spain, one in Mexico, one in Denmark, one in Portugal, and one in Malaysia. Of these studies, 28 were interventional studies, nine of which were conducted in cohorts living with obesity for which intermittent fasting was utilized as an obesity treatment. Fifteen were randomized controlled trials, eight cross-over trials, and five one-arm design. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the 28 interventional studies that included efficacy data, emphasizing intervention components, execution, feasibility measures, adherence monitoring, and primary and secondary outcomes. The remaining six studies were cross-sectional studies focusing on discussing and evaluating the cardiometabolic effects, parental acceptability, and eating behaviors in adolescents and young adults, without involving the experimental manipulation of timing of eating.

The sample size of included interventional studies ranged from eight to 141 participants, ages 12–25 years old36,37,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120. Of the interventional studies included, six focused on adolescents alone with a mean age of 15 and above up to 18 years, while 22 studies involved emerging adults with mean ages above 19 and below 25. Some studies included a majority of female participants (e.g., 64% in Vidmar et al.36, while others only included male participants (e.g., 100% males in McAllister et al.104 and Harder-Lauridsen et al.104,113. A few studies reported an approximately even sex distribution103,116. Participants’ baseline weight status also varied widely, from those with a median or mean weight indicating overweight or obesity (e.g., median weight = 101.4 kg in Vidmar et al.36 to those with participants in the normal weight range (e.g., mean Body mass index = 22.7 kg/m² in Park et al.102. Seventeen studies included participants with normal mean or median weight, while 11 studies involved participants with overweight or obesity. Regarding health status, most studies included generally healthy participants without significant comorbidities, chronic conditions, or medication use98,99,100,102,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,116,117,118,119. However, one study specifically included participants with type 2 diabetes97.

Interventional studies focused on the efficacy or effectiveness of intermittent fasting interventions on exercise performance, body composition, body weight, metabolism, and/or biological aging markers, as summarized in Table 136,37,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120. Nine studies utilized intermittent fasting as an obesity treatment for cohorts of young people with obesity. The primary outcomes varied, which involved assessing the efficacy of various intermittent fasting interventions on body weight, body composition, cardiometabolic health markers, energy balance, and specific physiological responses such as glycemic control and muscle damage indicators. Secondary outcomes were also diverse and included assessments of dietary intake quality, physical activity, sleep patterns, eating behaviors, quality of life, glycemic control, blood biomarkers, microbial diversity, muscular performance, hunger, craving, mood, cognitive function, appetite, and energy intake responses. Most interventional studies involved interventions with short duration, spanning 4–12 weeks, which limits conclusions about long-term efficacy and safety. Among these studies, 23 were randomized controlled trials36,97,99,100,101,103,104,105,109,110,112,113,115,121 and five were single-arm trials37,98,102,111,114. Thirteen studies utilized an 8-h time-restricted eating, where participants follow an 8-h eating window and a 16-h fasting period36,97,98,100,101,102,104,105,108,110,111,112,115, and three tested other forms of intermittent fasting, including Alternate-Day Calorie Restriction113, Intermittent Energy Restriction121, and Protein-Sparing Modified Fast114. Other studies investigated different time-restricted eating windows or other intermittent fasting protocols. For instance, Zhang et al.103 compared early (7:00 a.m.–1:00 p.m.) and late (12:00 p.m.–6:00 p.m.) 6-h time-restricted eating windows103, and Bao et al.107 tested the efficacy of a 5.5-h time-restricted eating window compared to an 11-h eating control group107.

The intervention modalities varied across studies. Fifteen studies involved multimodal interventions combining time-restricted eating with various other health and behavioral lifestyles modalities including, continuous glucose monitoring, resistance training, energy restriction, low carbohydrate and added sugar diets, brisk walking, high-intensity exercise, antioxidant supplementation, and protein-sparing modified fasts. The specific details of the IF approach also varied by study. Only one study directly compared early and late time-restricted eating103, whereas all others compared the IF approach to a control condition. In addition, the caloric requirements integrated into the IF approach varied across studies, with some implementing isocaloric conditions (maintaining the same caloric intake)97,104, energy restriction (e.g., 25% calorie deficit, very low-calorie diets)109, and intermittent fasting days such as alternate day fasting37 and intermittent energy restriction109. Specific interventions like the protein-sparing modified fast had defined caloric intake ranges (1200–1800 calories with low carbohydrate and high protein)114.

Table 2 presents an overview of the interventional studies, cataloged by the results reported. There was great heterogeneity in how feasibility was defined across various study designs. None of the studies utilized the seven Theoretical Framework of Acceptability components. A few of the individual components of the framework were captured: 6/28 affective attitude, 3/28 burden, 0/28 ethicality, 0/28 intervention coherence, 0/28 opportunity costs, 1/28 perceived effectiveness, and 0/28 self-efficacy.

Nine studies were conducted in cohorts of young people with obesity utilizing intermittent fasting as an obesity treatment36,37,97,98,103,110,111,114,121. Most of the remaining studies captured changes in weight as a secondary outcome despite the primary objective of the intervention not being weight change. There was a variety of weight status and body composition measures utilized across studies. The most commonly reported measures were the following: change in weight, pre and post weight, pre and post body mass index, and change in weight in excess of the 95th percentile. All nine studies that included young people with obesity reported significant improvement in at least one weight-related outcome following the intermittent fasting program compared to baseline36,37,97,98,103,110,111,114,121, and only one study reported significant weight loss after following a 6-h time-restricted eating for 8 weeks compared to the control group (ad libitum diet)103.

Overall, studies utilizing intermittent fasting interventions in adolescents and young adults have demonstrated variable effects on weight loss, influenced by factors such as intervention type, participant demographics, and additional lifestyle components. Vidmar et al.36 conducted a randomized controlled trial with 45 adolescents (mean age = 16.4 years, 64% females) over duration of 84 days to examine the efficacy of late time-restricted eating in adolescents with obesity. All groups experienced weight loss, with 31% of the participants in the time-restricted eating plus continuous glucose monitoring group, 26% in the time-restricted eating with blinded continuous glucose monitoring group, and 13% in the control group losing ≥5% of their baseline weight. The study reported no significant difference in weight loss between groups (p = 0.5). Overall, there was a significant decrease in median weight, body mass index z-score, and weight in excess of the 95th percentile across all groups36. Hegedus et al.97 reported a significant decrease in body mass index at the 95th percentile at week 12, with a 46% reduction observed in the late time-restricted eating group compared to 21% in the control group with an extended eating window97. Zhang et al.103 observed decreases in weight and body mass index in both early and late time-restricted eating groups compared to controls103. In Moro et al.105 study, the time-restricted eating group experienced a 2% weight change from baseline, while this was not the case for participants assigned to the control group105. Park et al.102 documented significant weight loss among female participants, while no significant weight loss was observed among male participants102. In contrast, research examining the combination of time-restricted eating with resistance training offers a different perspective99,100. Tinsley et al.100 investigated the effects of an 8-h time-restricted eating combined with β-hydroxy β-methylbutyrate supplementation and resistance training in active females, only to find an increase in body weight across all groups100. Similarly, a study by Tinsley et al.99 on a 4-h time-restricted eating regimen coupled with resistance training in men reported no significant change in body weight99, indicating that when combined with resistance training, time-restricted eating may not lead to weight loss, possibly due to increases in muscle mass or other physiological adaptations. This suggests that the efficacy of time-restricted eating on weight loss might be influenced by factors such as biological sex, baseline weight, and exercise regimens.

Regarding cardiometabolic outcomes, 19 studies reported one or more cardiometabolic outcomes. Several studies reported improvements in markers of glucose metabolism97,102,103 For instance, Hegedus et al.97. found reductions in hemoglobin A1c and alterations in C-peptide levels in late time-restricted eating groups97. Kim and Song observed reductions in fasting blood glucose and improvements in HOMA-IR, indicating better glucose regulation and insulin sensitivity with early time-restricted eating111. Zhang et al.103 highlighted a decrease in insulin resistance after a self-selected 8-h time-restricted eating103. One study also reported reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure following an 8-h time-restricted eating104. Conversely, two studies (one employing alternate day fasting and the other 4-h time-restricted eating)37,99 observed no metabolic changes compared to baseline. Another study reported significant reductions in fasting insulin, acyl ghrelin, and leptin concentrations during short-term energy deprivation compared to energy balance. Postprandial hormone responses, including insulin, GLP-1, and PP, were elevated after energy deprivation, while acyl ghrelin was suppressed, indicating that altered sensitivity to appetite-mediating hormones may contribute to the adaptive response to negative energy balance96. Overall, these findings suggest that intermittent fasting can improve glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity, though results may vary based on the specific fasting protocol and participant characteristics.

McAllister et al.104 and Zhang et al.103 noted decreases in body mass and fat mass in participants adhering to time-restricted eating, while preserving lean mass103,104. Additionally, time-restricted eating was associated with decreased liver enzymes aspartate aminotransferase and alanine transaminase in two studies97,101. McAllister et al.104 reported increases in high-density lipoprotein and variations in low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol depending on the type of time-restricted eating (ad libitum vs. isocaloric)104. Zeb et al.101 found decreased total cholesterol and triglycerides, and an increase in high-density lipoprotein post-time-restricted eating101 However, divergent effects on lipid profiles were observed as well, with increases in high-density lipoprotein101,104 as well as in low-density lipoprotein102,103. These mixed results on lipid profiles indicate that intermittent fasting may have variable effects on lipid metabolism, potentially influenced by factors such as fasting duration, diet composition, and individual metabolic responses.

Only four studies measured markers associated with biological aging101,103,104,105. McAllister et al.104 and Moro et al.105 both reported an increase in adiponectin levels in participants following an 8-h time-restricted eating regimen, whether combined with an ad libitum diet or an isocaloric diet. Elevated adiponectin levels are inversely associated with obesity and oxidative stress and correspond to improved metabolism and resting energy expenditure104,105. Additionally, Moro et al.105 observed a significant decrease in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, an inflammatory marker, within the time-restricted eating groups compared to controls, indicating reduced inflammation105. Zeb et al.101 observed reductions in serum IL-1B and TNF-a levels post-time-restricted eating, though these changes were not statistically significant, suggesting a potential trend towards reduced inflammation that warrants further investigation101. Zhang et al.103 reported that superoxide dismutase, a crucial antioxidant defense in nearly all living cells exposed to oxygen, significantly increased in participants who engaged in early time-restricted eating compared to those in late time-restricted eating and control groups103.

Most of the studies did not report serious adverse events or behavioral reactions. However, one study observed that while most participants did not experience adverse events121, eight serious events occurred across six participants, with two possibly related to the intervention. Specifically, one participant in the continuous energy restriction group developed gallstones requiring cholecystectomy, and another in the intermittent energy restriction group developed atypical anorexia nervosa121. A few studies noted mild side effects such as dizziness and loss of concentration100,110. Additionally, some studies reported that only a few participants experienced conflicts with work or sleep schedules, social commitments, and explaining eating patterns to family36,97. Regarding behavioral reaction concerns, only one study, Thivel et al.117, observed that when participants were allowed to eat freely after a period of 24 h of energy intake restriction, they consumed significantly more food during the test meal. This reaction did not occur when the energy depletion was caused by exercise117.

All included observational studies were cross-sectional studies, and they varied in their focus. One study addressed parental interest in time-restricted eating, while others focused on intermittent fasting’s effects on cardiometabolic markers and the associated concerns with intermittent fasting122,123,124,125,126,127. Tucker et al.122 found that two-thirds of parents with children in pediatric weight management programs showed interest in time-restricted eating for ≤12 h per day, with interest waning for stricter limits of ≤10 or ≤8 h122. Observational research examining the relationships between the timing of eating, weight management outcomes, and cardiometabolic risk factors suggests there is no meaningful impact on body composition. However, there may be benefits to cardiometabolic health from adopting earlier and shorter eating windows124,125,126. Nevertheless, skipping breakfast was associated with increased cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescence, as observed in a cross-sectional survey study by de Souza et al.123. Another study reported that diets low in carbohydrates and those involving intermittent fasting were linked to increased disordered eating behaviors, including binge eating and food cravings. These findings suggest that such restrictive diets may heighten cognitive restraint, leading to an upsurge in food cravings. However, this study’s reliance on a cross-sectional design and a web-recruited university sample, predominantly female, introduces potential biases127.

Discussion

This scoping review catalogs published studies of intermittent fasting interventions in young people up to age 25. The review included 34 studies (9 randomized controlled trials in cohorts with obesity intended as a treatment approach) and revealed that there is great heterogeneity in study design, methodology, feasibility measures, adherence monitoring, and intervention components across studies of intermittent fasting in adolescents and young adults. The diversity of methodologies and outcomes makes it challenging to summarize the overall efficacy of intermittent fasting as a treatment option in youth with obesity36,37,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120. While intermittent fasting interventions have the potential to be a feasible and acceptable treatment approach for young people with obesity, the current results highlight the need for rigorous studies to investigate feasibility of intermittent fasting utilizing standardized theoretical frameworks for acceptability95. This is crucial as an initial step when evaluating new interventions to allow for comparability across studies and cohorts128,129. As highlighted in the results; the majority of the studies included captured one to three of the seven recommended components associated with the acceptability framework95; however, none utilized all seven components in their entirety. In addition, the majority captured this data via self-report and open-ended questionnaire with very little qualitative data to drive conclusions regarding feasibility and acceptability of intermittent fasting interventions in this age group.

Furthermore, the intervention components investigated varied significantly. This was not only found among what form of intermittent fasting intervention was studied but what additional components of the intervention were included36,37,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120. It very well may be that intermittent fasting based interventions can act as a synergistic intervention to other multi-component health and behavior approaches37,99,100,109,110,111,112,114,117,119, but the studies cannot truly be compared for efficacy when the interventions are not similar in their components. Each intermittent fasting approach may be uniquely suited to a specific individual’s preferences, life stage, and resources. Thus, large, well-designed feasibility and efficacy trials should be performed for each intermittent fasting approach compared to a control arm that is standardized across study designs to allow for comparability. In pediatric practice, investigators may consider utilizing a multidisciplinary, family-based intervention model given that is the most utilized health and behavioral lifestyle intervention implemented in this age group6,10,11.

Time-restricted eating approaches were the most studied form of intermittent fasting used as an obesity treatment included in this review36,97,98,101,102,104,105,108,110,111,112,115. Even among time-restricted eating interventions, there remains significant opportunity for diversity in the approach, which affects the comparison of outcomes across studies28,78,130. Despite, studies utilizing different anthropometric measures those studies investigating the effects of time-restricted eating on weight reduction in young people showed similar results to previously published systematic reviews of time-restricted eating in adults with obesity. For example, at week 12 compared to baseline, Jebeiele et al. reported a within subjects’ reduction in weight in excess of the 95th percentile of −5.6% ± 1.1 (n = 30)37; Hegedus et al. reported a with-in-subject reduction in weight in excess of the 95th percentile of −4.3% ± 5.76 (n = 35)97; and Vidmar et al. reported a with-in subject reduction in weight in excess of the 95th percentile of −3.4% ± 1.2 (n = 13)36. These findings are similar to outcomes reported with other healthy and behavioral lifestyle modification interventions such as very low-energy diet programs or multi-disciplinary family-based on intervention which often show a 3-5% body mass index reduction after program completion131,132,133. As shown in the results, the timing of the eating window varied by study design with the majority allowing for a participant-identified eating window followed by an afternoon/evening window. This variation in study design highlights a key aspect of intermittent fasting research: understanding the biological mechanisms that lead to improvements in weight and cardiometabolic health across all age groups living with obesity24,57,134. There remains debate as to which eating window is most preferred by participants as well as which eating window results in the greatest improvement in weight and cardiometabolic outcomes when adhered to well97,124,126,135,136,137. Further research is needed to understand both of these questions and understand the mechanisms underlying intermittent fasting interventions. Additionally, there is a need for a pragmatic approach to disseminate this type of intervention in real-life settings to optimize engagement and sustained efficacy124.

Given that adherence to treatment recommendations is the strongest predictor of outcomes; rigorous adherence monitoring is needed in the assessment of novel intervention approaches to accurately assess efficacy7,8,9,10. There was great variety in the methods utilized to capture adherence to the intervention across studies36,104,108, limiting comparability as well as the ability to assess how the dosage of the intervention received affected the primary outcome of interest. To advance the field of intermittent fasting interventions, it is crucial to determine the best practices for implementing and disseminating these interventions in pediatric cohorts6,17,21. Despite the limitations described above, the preliminary efficacy discussed in the reviewed articles exploring the effects of intermittent fasting on weight loss and cardiometabolic outcomes is consistent with findings reported in adult cohorts 24,33,35,69. These few studies indicate that intermittent fasting, especially time-restricted eating, can significantly improve weight loss, body composition, and metabolic health, with potential benefits against metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in adolescent and emerging adult cohorts97,104,111. However, due to heterogeneity in methodology and quality of the evidence, it is challenging to compare the efficacy across studies. Moreover, in adults intermittent fasting interventions have been shown to have positive effects across other clinical outcomes such as aging, oxidative stress, and inflammation33,34,49,65. The current results show the gap in mechanistic data that is available on how intermittent fasting interventions affect these other complex clinical outcomes that may have significant relevance to the long-term benefits for young adults33,138,139.

Finally, this review draws attention to both the gaps in research regarding the use of intermittent fasting in adolescents and emerging adults and the opportunities. One review study evaluated the impact of the timing and composition of food intake, physical activity, sedentary time, and sleep on health outcomes in youth, suggesting that these factors independently predict health trajectories and disease risks. This underscores the need for a unifying framework that integrates time-based recommendations into current health guidelines for children and adolescents21. Expanding diverse nutrition interventions that are developmentally appropriate, practical, and easy to implement across communities and age groups is essential4,6,17,21. Intermittent fasting uniquely allows individuals to maintain control over their food choices within a specified eating window17. This flexibility in choosing foods, selecting an appropriate eating window, socializing during meals, and dining out without dietary restrictions distinguishes intermittent fasting as a dietary strategy that fosters sustainable behavioral change for an age group in which autonomy is expanding21,36. Given that adolescence is a period of growing independence, reflected in food choices and time management140, further research is needed to understand adolescent and emerging adult eating patterns and frequencies and how those patterns may affect intervention implementation and dissemination. There does remain some concern among the pediatric community relating to the association between dietary restraint and eating disorder risk as well as inhibiting growth in youth participating in intermittent fasting127,141. This concern is certainly not isolated to intermittent fasting approaches and is something that the clinical and scientific are working to investigate closely as we thoughtfully treat young people living with obesity. In 2019, a systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between obesity treatment with a dietary component and eating disorder risk in children and adolescents142. The results demonstrated that professionally supervised dietary interventions are associated with improvements in other markers of eating disorder risk, in contrast to adolescents dieting on their own142. Similarly, Jebeile et al.143 reported that intensive dietary interventions did not worsen mental health or eating behaviors in adolescents with obesity; instead, they observed improvements in symptoms of depression and disordered eating, alongside reductions in BMI and cardiometabolic parameters143. Many of the included trials examined in this review investigated the effect of intermittent fasting interventions on eating behaviors. Jebeile et al., Hegedus et al., and Vidmar et al. each captured and highlighted that in their pilot cohorts, there was no evidence of negative compensatory eating behaviors that occurred over the study period as the participants engaged in intermittent fasting approaches36,37,97. Despite limited data, in small sample sizes, the current published evidence suggests consistent with other literature in this area, that with proper guidance, youth with obesity, can adhere to intermittent fasting protocols safely without negative effects on eating behaviors21,36,37,97,142. Additional large trials of intermittent fasting in youth with obesity are needed to determine if intermittent fasting is an effective treatment strategy for weight reduction and cardiometabolic improvement in this age group. To date, the minimal evidence seems to support its feasibility and acceptability.

To our knowledge, this is the first review of intermittent fasting evidence among adolescents and young adults. The summary of available studies’ methodology, intervention parameters, outcomes selected, feasibility, and efficacy fill an important gap in informing future research priorities. While comprehensive in its scope, the review also has several inherent limitations that could influence the interpretation and applicability of its findings. First, this review’s ability to draw generalizable conclusions is challenged by the inherent heterogeneity in design, duration, sample size and characteristics, and methodologies. This variability hinders the broad-picture interpretation of intermittent fasting’s efficacy. Particularly concerning is the lack of consistency in capturing intervention adherence. Dosage of the intervention is directly associated with efficacy and thus must be included to ensure efficacy accurately reflects the effect of the intervention. The short duration of many studies on intermittent fasting involving adolescents and emerging adults, limits the understanding of intermittent fasting’s long-term effects on growth, development, and overall health in this demographic. Additionally, the potential for publication bias, where studies with positive or significant results are more likely to be published than those with negative or inconclusive findings, could inadvertently skew the review’s findings in favor of intermittent fasting. The exclusion of gray literature and non-English texts may further introduce bias, potentially overlooking relevant findings not captured in the mainstream or English-speaking research community. Moreover, the review’s approach did not extend to quantifying the quality of reporting or to an in-depth exploration of the methodological quality of the included studies, leaving a gap in our comprehension of the strength and reliability of the evidence base.

In conclusion, our scoping review of 34 studies on intermittent fasting among adolescents and emerging adults highlights significant variability in methodologies, intervention components, feasibility measures, and adherence monitoring, which complicates the assessment of studies’ quality and comparability. Current findings from this scoping review are insufficient to make strong recommendations for or against intermittent fasting in adolescents and young adults. This review underscores the need for rigorous studies using standardized theoretical frameworks for acceptability and feasibility to enable comparability across studies and cohorts. This is crucial to determine the practicality and sustainability of intermittent fasting interventions in this age group before providing definitive guidance. Further research, especially long-term studies, is essential to better understand intermittent fasting’s impact on youth, develop standardized methodologies, and ensure protocols that promote adherence and confirm clinical efficacy.

Responses