Intrinsic second-order topological insulators in two-dimensional polymorphic graphyne with sublattice approximation

Introduction

The exploration of topological insulators (TIs) has significantly advanced our understanding of condensed matter physics over recent decades1,2,3,4,5, while current research on higher-order topological insulators (HOTIs) marks a new frontier in the study of topological phases6,7,8,9,10,11. HOTIs are characterized by unique in-gap states localized at higher co-dimensional boundaries, namely corner or hinge states9. These states are termed “intrinsic” when they arise from spatial symmetries that reverse the mass term at edges or surface intersections12,13. This reversal, governed by bulk symmetries, ensures the presence of corner or hinge states as long as the bulk band gap remains open13. In contrast, extrinsic HOTIs lack this bulk protection, so that the presence of their corner or hinge states depend on termination selection13.

In two-dimensional (2D) systems, higher-order topological states are uniquely confined to corners, defining what are known as second-order topological insulators (SOTIs)9. It has been shown that the topological classification of intrinsic corner states aligns with certain Altland-Zirnbauer classes in one dimension11. Consequently, intrinsic corner states can only exist within five out of the ten Altland-Zirnbauer classes, i.e., AIII, BDI, D, DIII, and CII, where either chiral or particle-hole symmetry is essential11,14. From another perspective, corner states may shift towards bulk states unless chiral or particle-hole symmetry anchor them precisely at the zero energy15,16. This symmetry requirement poses significant challenges in realizing intrinsic second-order topological states in 2D materials. Notably, recent studies have reported the emergence of SOTIs in two dimensions, thereby expanding the understanding of higher-order topological phases17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. However, within these materials, chiral and particle-hole symmetries, emerging as approximations, have been observed in a few cases, notably in graphyne17,19 and graphdiyne20,21,22. In other scenarios, such as fragile topological insulators (FTIs)44,45,46,47,48,49,50, obstructed atomic insulators (OAIs)51,52,53,54,55, and boundary-obstructed topological phases (BOTPs)16,56, this symmetry requirement is not necessary, and corner states may hybridize with bulk states or disappear as gaps close within valence bands or edge states16.

In this work, we contribute to this dynamic field by examining the symmetry conditions necessary for intrinsic 2D SOTIs, focusing specifically on class BDI, and exploring their material realization based on sublattice approximation. By analyzing the transformation of an angle-dependent edge Hamiltonian under 2D point group symmetries, we identify potential positions for intrinsic corner states, which depend on whether the spatial symmetries commute or anticommute with the chiral symmetry. We also identify several ideal candidates in polymorphic graphyne for realizing intrinsic 2D SOTIs with sublattice approximation, highlighting a promising strategy for achieving observable topological corner states. The signatures of higher-order topological phases are revealed through first-principles calculations, offering potential for observing corner states in 2D SOTIs.

Results

Intrinsic corner states in class BDI

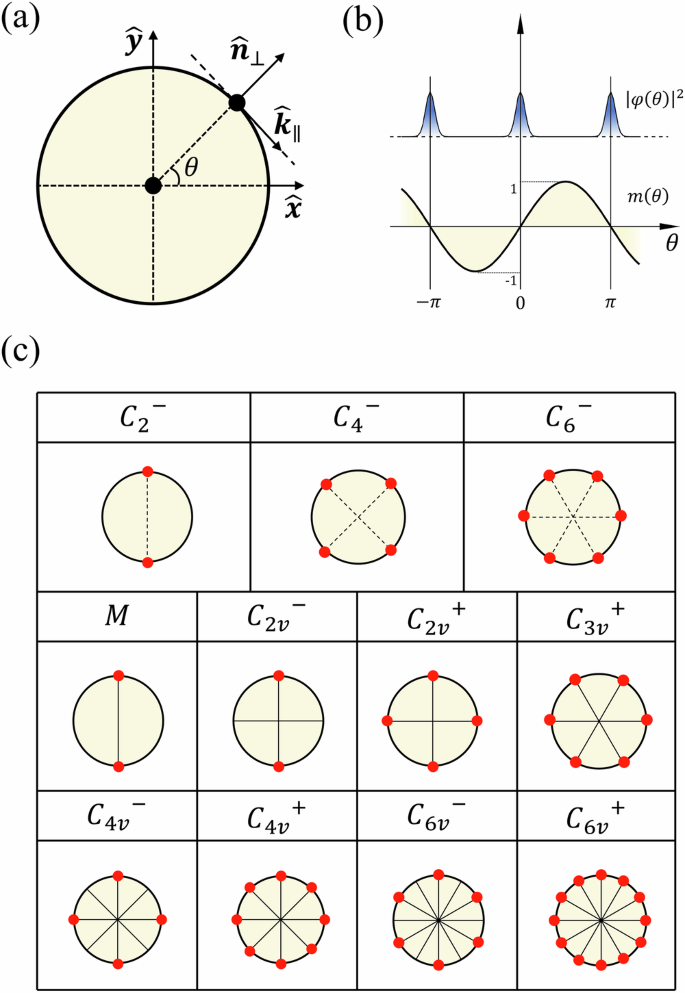

Class BDI is a category in the ten-fold way classification scheme defined by three non-spatial symmetries: time-reversal (({mathcal{T}})), particle-hole (({mathcal{P}})), and chiral (({mathcal{C}})) symmetries, with each satisfying the conditions ({{mathcal{T}}}^{2}=1,{{mathcal{P}}}^{2}=1), and ({{mathcal{C}}}^{2}=1)11,14. To clarify the symmetry conditions of intrinsic 2D SOTIs in class BDI, we begin with a 2D lattice designed to allow cuts in arbitrary directions, as shown in Fig. 1a. While spatial symmetries are broken at the boundary of this lattice, the three non-spatial symmetries retain their constraints. This results in edge states that, depending on the cut angle θ, mimic one-dimensional lattices categorized under class BDI. We employ a minimal Dirac Hamiltonian with only one mass term to describe the boundary states, represented as:

where σi(i = x, y, z) are Pauli matrices, k∥ is the momentum parallel to the edge, and m(θ) is a mass parameter. The Hamiltonian respects time-reversal symmetry ({mathcal{T}}=K) and anticommutes with chiral symmetry ({mathcal{C}}={sigma }_{z}). For spatial symmetries changing θ, the Hamiltonian undergoes transitions described by:

where R represents a spatial symmetry, UR is its matrix representation, and η takes the values ± 1 to indicate whether R is a proper or improper rotation. Akin to first-order topological boundary states that exist as domain walls between the bulk and vacuum, intrinsic corner states appear as domain walls along the edge at positions where the mass term changes sign, as shown in Fig. 1b. The presence of these states depends on finding a matrix representation of spatial symmetry that anticommutes with the mass term, satisfying

to meet the condition of Eq. (2). Moreover, spatial symmetries should be unitary and satisfy:

with ζ = ±1 determining whether the spatial symmetry commutes or anticommutes with chiral symmetry. Eqs. (3) and (4) necessitate ζ = − η for finding an appropriate matrix representation of spatial symmetries, specified by:

This implies that a proper rotation should anticommute with the chiral symmetry, while an improper rotation should commute with it, enabling the emergence of intrinsic corner states in 2D BDI systems.

a Diagram of a two-dimensional lattice with an edge that varies with θ, defined as the angle between the normal direction of the edge and the (hat{x})-direction. b Graph showing the variation of the probability density of the edge wave function and the mass parameter as a function of θ. c Diagram depicting the potential positions of intrinsic corner states in two-dimensional point groups within class BDI. A superscript + (−) indicates that minimal rotation symmetry commutes (anticommutes) with chiral symmetry. Solid lines represent mirror planes, while dashed lines serve as reference lines.

This analysis extends to 2D BDI systems under point group symmetries, where the potential positions of corner states are inferred from the relationships between the generators and chiral symmetry, as summarized in Fig. 1c. In two dimensions, improper rotations refer to mirror symmetries, while proper rotations relate to Cn symmetries for n = 2, 3, 4, 6. Along the edges of these systems, specific positions may be invariant under mirror reflections but not under rotations. Consequently, in point groups governed solely by rotation symmetries, the precise positions of intrinsic corner states remain unpredictable, although the total number of these states is conserved due to the bulk topological phase. Notably, Eq. (5) does not account for order-three operations, which require ({U}_{R}^{3}=pm I), thereby indicating that C3 rotations are incapable of generating intrinsic corner states. In point groups with mirror symmetries, intrinsic corner states are located at the mirror-invariant corners, where the mirror symmetries commute with the chiral symmetry. For point groups featuring both mirror and rotational symmetries, the generators can be chosen as the minimal rotation and a mirror, leading to scenarios where either all or only half of the mirror symmetries commute with the chiral symmetry, resulting in two distinct potential configurations for intrinsic corner states.

The minimal model of intrinsic 2D SOTIs

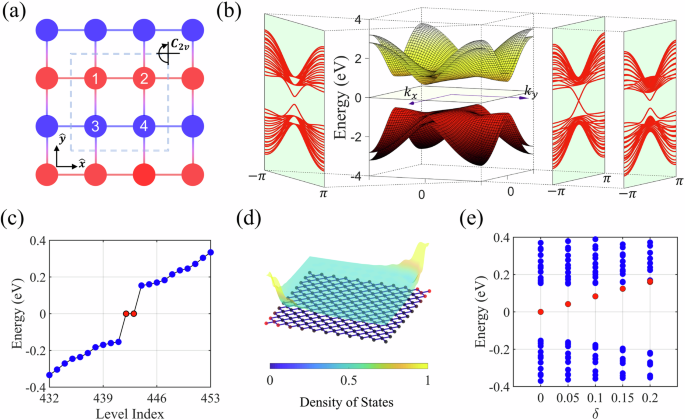

To illustrate these symmetry constraints, we consider a 2D lattice with point group C2v, as depicted in Fig. 2a. In crystals, chiral symmetry is typically achieved through sublattice arrangements with interactions confined to distinct sublattice groups, thus also being referred to as sublattice symmetry14. The chiral symmetry is represented by ({mathcal{S}}={tau }_{z}{sigma }_{0}) with eigenvalues ±1 for basis functions in distinct sublattice groups. This setup ensures that spatial symmetries mapping atoms within the same sublattice group commute with the chiral symmetry, while the opposite mappings indicate anticommutation. Moreover, such a representation ensures that the Hamiltonian is block-anti-diagonalized. The minimal Hamiltonian is expressed as:

where M and m are mass parameters in the bulk and along the edge, respectively. For any given edge orientation θ, the momentum components parallel (k∥) and perpendicular (k⊥) to the edge are considered. The edge Hamiltonian then reads:

aligning with Eq. (1) (refer to Supplementary Note 1 for a detailed derivation). Notably, symmetry-preserved terms in the bulk allow for a continuous transformation of the edge Hamiltonian, making it sufficient to consider only its minimal form. The mass term creates domain walls at θ values of (frac{pi }{2}) and (frac{3pi }{2}), corresponding to the Mx-invariant points along the edge, as indicated in the ({C}_{2v}^{-}) case in Fig. 1b, where Mx commutes with the chiral symmetry, while C2z and My anticommute with it.

a Schematic of a two-dimensional lattice under point group C2v showing primitive cells (dashed square) and atoms categorized into distinct sublattice groups (red and blue circles). b Three-dimensional representation of bulk band structures from the tight-binding model (parameters M = 1 and m = 0.2). The left plot illustrates the edge states along the y-direction, while the right plot depicts the edge states along the x-direction. The rightmost plot corresponds to δ = 0.2. c Energy levels of the tight-binding model for a nanodisk with 221 unit cells. The red points indicate the corner states. d Illustration of the nanodisk and the electronic charge density associated with the corner states. e Energy levels of the nanodisk as a function of δ.

To simulate the situation in a periodic lattice, we incorporate periodicity into the Hamiltonian from Eq. (7), reformulated within a tight-binding model as follows:

As shown in Fig. 2b, this model predicts a gapped bulk band structure across the entire Brillouin zone. Edge calculations reveal that edge states emerge within the gap of the projected bulk states, which are gapped along the y-direction and gapless along the x-direction. This gapless nature is safeguarded by the Mx symmetry, which commutes with the chiral symmetry, implying the presence of intrinsic corner states at the Mx-invariant corners. In Fig. 2c, energy level calculations for a nanodisk comprising 221 unit cells identify two corner states exactly at zero energy, with their electronic charge densities highly localized at two Mx-invariant corners in Fig. 2d.

Given that the chiral operator anticommutes with the Hamiltonian, each eigenstate is paired with a counterpart of opposite eigenvalue, resulting in the energy spectra exhibiting vertical symmetry about zero energy, as shown in Fig. 2b, c. This symmetry serves as a criterion for determining the presence of chiral symmetry in the system. When chiral symmetry is broken, such as through hoppings within the same sublattice, this symmetric pattern is disrupted. We introduce a δτxσ0 term to induce this chiral symmetry breaking. As shown in Fig. 2b, when δ = 0.2, the edge states are no longer symmetric about zero energy, and a gap opens in the spectrum. The energy levels in Fig. 2e show that the corner states move away from zero energy as δ increases, eventually merging into the bulk states. In realistic materials, such symmetry-disrupting terms are hard to eliminate, but their influence can be minimal if δ → 0, which is a condition referred to as the “sublattice approximation”.

Intrinsic corner states in polymorphic graphyne

While particle-hole and chiral symmetries can be strictly enforced in simplified tight-binding models, reproducing these conditions in actual materials poses significant challenges. To demonstrate the effect of these symmetries in crystals, we employ a sublattice approximation, exemplified through our investigation of carbon-based polymorphic graphyne, known for its sp and sp2 hybridized bonds and considerable material design potential. Our prior work has extensively detailed the structural construction methodology and identified several structurally stable materials57. Herein, we delve into the higher-order topological properties of GY-1-5, a representative polymorphic graphyne configuration, to underscore its utility in studying intrinsic 2D SOTIs. Additional materials can be found in Supplementary Note 2.

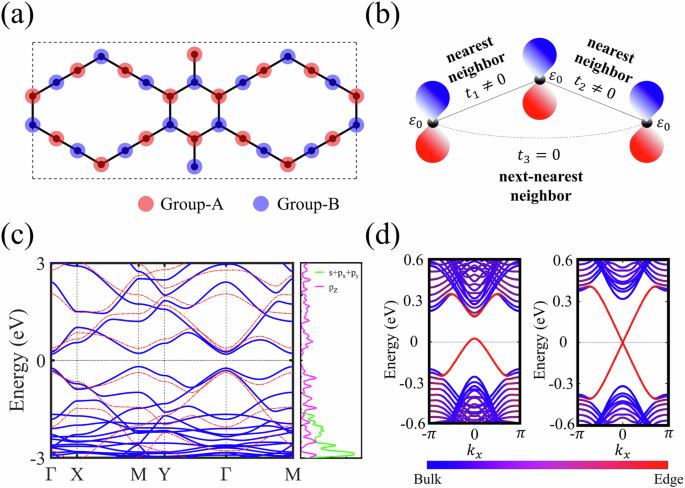

The lattice of GY-1-5 belongs to the plane group p2mm and contains 30 atoms in its primitive cell, as shown in Fig. 3a. The optimized lattice constants are a = 16.38 Åand b = 6.91 Å. The band structure of GY-1-5 is illustrated in Fig. 3c, which exhibits a semiconductor band gap of 0.38 eV. Near the Fermi level, we observe a nearly vertically symmetric pattern, indicating the presence of approximate sublattice symmetry in this material. In Fig. 3c, we present the projected density of states (PDOS) for the s and p orbitals, emphasizing that the bands near the Fermi level primarily originate from the pz orbital. Due to their high localization, non-nearest neighbor hoppings are substantially weaker than those between nearest neighbors. Given the uniformity of the element constituting the atoms, we can approximate that all pz orbitals possess similar onsite energies, allowing us to categorize the atoms into two distinct sublattice groups, as marked in Fig. 3a, thus ensuring minimal interactions within the same group.

a Lattice structure of GY-1-5. The dashed box represents the primitive cell. The Wyckoff positions of the atoms include 2h at (0.5,0.29) and (0.5,0.91), 2g at (0.0,0.39), and 4i at (0.42,0.40), (0.35,0.71), (0.29,0.79), (0.21,0.90), (0.14,0.21), and (0.07,0.29). Red and blue circles represent atoms in distinct sublattice groups. b Schematic diagram of onsite energies (ε0) and hopping parameters (t1, t2 and t3) between the nearest and next-nearest neighbor pz orbitals with sublattice approximation. c Band structures of GY-1-5 without (solid blue lines) and with (red dashed lines) sublattice approximation. The right panel illustrates the partial density of states for the pz and other orbitals of GY-1-5. d Edge states along the x-direction of GY-1-5 without (left panel) and with (right panel) sublattice approximation.

To compare the cases without and with sublattice approximation, we construct a Wannier tight-binding (TB) Hamiltonian using the maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWF) method with the WANNIER90 package58,59. The band structure of GY-1-5 with sublattice approximation is shown by the dashed lines in Fig. 3c, displaying an accurate vertically symmetric pattern. This approximation is introduced by retaining only the energy bands contributed by pz orbitals, preserving solely nearest-neighbor interactions, and unifying all on-site energies, as depicted in Fig. 3b. As previously analyzed, intrinsic corner states protected by the point group 2mm should appear at the mirror-invariant corners, where the mirror operation commutes with the chiral symmetry. As shown in Fig. 3a, the effective mirror operation is Mx, as it maps atoms within the same sublattice group. As shown in Fig. 3d, the edge states along the x-direction transition from gapped to gapless when the sublattice approximation is applied, implying the presence of intrinsic corner states at the Mx-invariant corners.

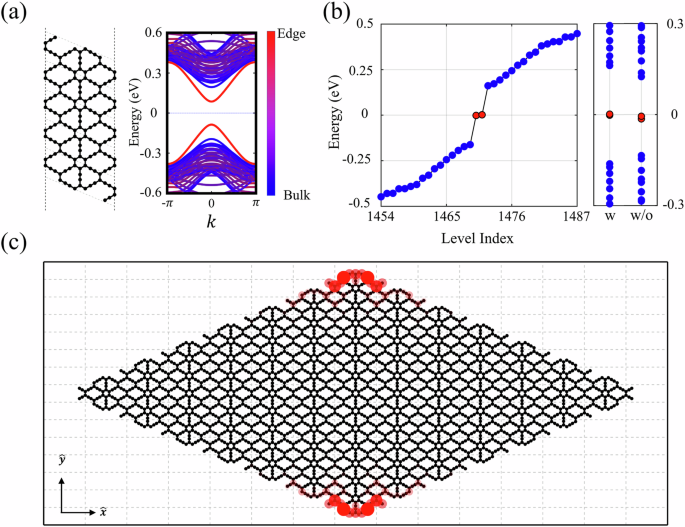

To intuitively display the intrinsic corner states, we construct a nanodisk with Mx-invariant corners aligned with the edges in the [11]-direction. Using the TB Hamiltonian with sublattice approximation, we show the gapped edge states along the [11]-direction in Fig. 4a, which corroborates the edge Hamiltonian described by Eq. (1). We then calculate the energy spectrum of the nanodisk, as shown in Fig. 4b, where two states emerge precisely at the Fermi level, representing the zero modes of the intrinsic 2D SOTIs. These states are firmly anchored at the Fermi level due to chiral symmetry constraints, with minor energy variations attributable to finite-size effects that diminish as the nanodisk size increases. The electronic charge density of these zero modes is shown in Fig. 4c, which exhibits pronounced localization at the two Mx-invariant corners. In the realistic case without sublattice approximation, the energy levels of corner states deviate slightly from the Fermi level, as shown in Fig. 4b. Nevertheless, the corner states remain well within the central region of the bandgap, which is a consequence of the approximate chiral symmetry in this material, thereby facilitating observation.

a Edge states of GY-1-5 along the [11]-direction with sublattice approximation. The cutting edge is shown in the left panel. b Energy levels of a nanodisk with 2940 atoms with sublattice approximation. The red points indicate the intrinsic corner states. The right panel compares the energy levels with (w) and without (w/o) sublattice approximation. c Illustration of the nanodisk and the density of states for the intrinsic corner states.

The intrinsic corner states protected by chiral symmetry can also be understood through band representation analysis based on real-space structures (see details in Supplementary Note 3). This analysis explores possible band connections constrained by compatibility relations and correlates them with Wyckoff positions in real space using an adiabatic approximation51,52,60. We found that GY-1-5 exhibits features of OAIs, where the elementary band representations for unoccupied maximal sites must reside in the valence bands. However, unlike typical OAIs, the presence of chiral symmetry, which determines the occupation of electronic states, plays a critical role in generating corner states. Moreover, GY-1-5 exhibits combined ({C}_{2}{mathcal{T}}) symmetry, ensuring that the second Stiefel–Whitney class is well-defined44,47,48,49,50. We calculated the first and second Stiefel–Whitney numbers using the parity criterion associated with C2 symmetry, finding that w1x = w1y = 0 and w2 = 1. This indicates that GY-1-5 conforms to the second Stiefel–Whitney class of HOTIs (see details in Supplementary Note 4).

Discussion

In conclusion, our work provides valuable insights into the underlying principles for realizing intrinsic second-order topological insulators (SOTIs) in two dimensions, particularly within class BDI. We establish the symmetry conditions essential for the emergence of intrinsic corner states and offer practical guidelines for the material realization of intrinsic SOTIs using sublattice approximation. Our theoretical arguments are supported by first-principles calculations on polymorphic graphyne materials, which exhibit the potential to generate diverse symmetries through artificial design. These materials are ideal candidates for investgating the topological properties of intrinsic 2D SOTIs and for facilitating the observation of topological corner states. It should be noted that the presence of substrates can significantly affect the electronic properties and consequently the topological features of graphyne. Metallic substrates may disrupt the topological properties, while insulating substrates with van der Waals interactions are more likely to preserve them. The choice of substrate is therefore crucial in maintaining the desired higher-order topological effects in two-dimensional materials like graphyne.

Methods

Our first-principles electronic structure calculations are conducted using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)61 within the framework of density functional theory (DFT)62,63. We employ the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) for the exchange-correlation functional, utilizing the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) formalism64. The electronic wave functions are expanded in a plane wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 500 eV to ensure convergence. To adequately sample the Brillouin zone, we use a 4 × 8 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid65, which provides the necessary resolution for accurate calculations. To obtain the Wannier tight-binding Hamiltonian, we utilize the maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWF) method by selecting the pz orbitals as basis functions implemented in the WANNIER90 code58,66.

Responses