It is time to reevaluate the lard in glucose homeostasis and diabetes pathogenesis

Relationship between lard and diabetes in China

A number of studies with results which support this hypothese were found. For example, in 1980, the prevalence of diabetes in residents of Hui nationality (who do not eat lard and pork) in Ningxia, China, was 1.946%—treble the average prevalence of the Chinese population. A survey from Jiaozuo city of Henan province in China showed the prevalence of diabetes to be 38.6% in residents of Hui nationality and 8.3% in residents of Han nationality (who eat lard and pork)3. The same phenomenon was found in Changde city of Hunan province, where the prevalence of diabetes was 38.9% in Hui residents and 7.6% in Han residents, with levels of 46.15 and 8.55%, respectively, in men4. Those people with diets that excluded lard had a fourfold higher prevalence of diabetes than those whose diets included lard.

Furthermore, the Dongxiang ethnic group in China abstains from pork consumption. A survey conducted in rural areas of Gansu Province revealed that the prevalence of diabetes among Dongxiang individuals was higher compared to Tibetan and Han populations. Given similar living conditions and habits, dietary practices may account for this observed difference5. Another statistical study, performed by the hospital in Karamay City of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, compared diabetic complications morbidities between those of Han nationality and those of Uygur nationality (who do not eat lard and pork). Among 1284 clinical cases (774 Han, 510 Uygur), there were 3.1 times the number of cases of diabetic foot, 2.67 times the coronary heart disease, 1.73 times the hyperlipemia, and 2.38 times the fatty liver cases in those of Uygur nationality6.

The gradual Westernization of dietary patterns has contributed to a steady increase in the prevalence of diabetes in China. Data indicate that China’s vegetable oil consumption in 2019 experienced the most significant increase in recent years, coinciding with the highest growth rate of diabetes patients in China during the same period7.

The conditions in different countries

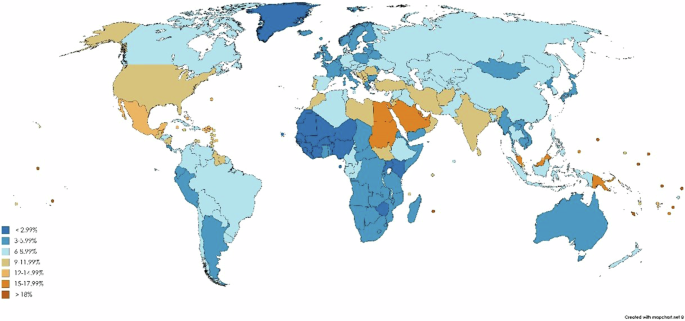

Statistics from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) for 2019 showed similar relevance between lard-related dietary patterns and morbidities of diabetes. We grouped areas around the world according to whether lard and pork is consumed or not; the former includes countries of the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia (Pakistan, India, Bangladesh), Malaysia, and Indonesia. As shown in Fig. 1, the incidence of diabetes is two to five times higher in these countries than in those where lard and pork are consumed. This is consistent with the hypothesis we proposed earlier.

Global diabetes incidence varies by country, with distinct colors indicating different levels. Countries in the Middle East, North Africa, the Indian Peninsula, and the South Pacific islands, where diets typically exclude lard, exhibit elevated rates of diabetes. Original data obtained from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas 201733.

The IDF for 2021 also showed that, inhabitants of the top 10 countries worldwide in terms of diabetic incidence—mainly located in the Middle East and Pacific islands—never or seldom consume lard and pork1. What is also conspicuous is that countries in South America have relatively low incidences of diabetes, but in Guyana and Suriname—where most residents do not consume lard and pork owing to religious reasons—the incidences of diabetes are higher than in the other South American countries.

Based on our hypothesis, we speculate that the development of the economy will see countries without lard consumption (including Africa, especially North Africa, the Middle East and Malaysia, and Indonesia in Southeast Asia) experiencing a deepening of the disaster of diabetes. This theory-based conjecture is consistent with the prediction for diabetic incidence by the IDF, which reported the regions which are forecasted to experience the largest relative growth in the number of people with diabetes are Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa, where dietary patterns feature little or no lard and pork1. Notably, the prevalence of diabetes in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Qatar have exceeded 23%; moreover, the average prevalence of diabetes among Arab-Israelis in Israel is up to 18.4%8. According to IDF predictions, morbidities of diabetes in these countries would rise to up to a shocking 40% in 2045.

There are some points of difference between the predictions of the IDF and our hypothesis. The IDF predicted that Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei will keep the 15% rate of increase, due to these regions being classified as part of the Western Pacific area. According to our hypothesis, however, the rates of increase in diabetes incidence should be ~80%—contributed to both by a diet excluding lard and pork, and rapid economic development. In Malaysia, for example, the incidence of diabetes in adults was 11.6% in 2006, 15.2% in 2011, and 17.5% in 20159; this is predicted to exceed 45%, rather than only 15%, in 2045.

Limitations of researches and biases of dietary guidelines

The latest “Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents (2022)” pointed out that animal fats are rich in saturated fatty acids, and the intake of saturated fatty acids should be controlled. The following year, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends replacing saturated fatty acids in the diet with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) (strong recommendation), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) from plant sources (conditional recommendation), or carbohydrates from foods containing naturally occurring dietary fiber, such as whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and pulses(conditional recommendation)10, This inevitably leads to a reduction in animal fats, which are rich in saturated fatty acids, and an increase in plant-based fats. In order to exclude residual confounders, in the last few decades, nutritional researches have been inclined to focus on the deficiency in or excess of certain single isolated nutrients, e.g., SFAs, PUFAs, n-3 and/or n-6 PUFAs, fructose, cholesterol, and certain vitamins. Yet the reality is much more complex: health effects are produced by smaller changes across several dietary factors, rather than prominent modification in a few individual nutrients11. Nutrition of foods needs to be evaluated objectively, a moderate amount maybe more appropriate than eating or not eating12. Based on our experimental results and the distribution of varying global prevalence of diabetes, we believe that an appropriate dietary intake of lard—which usually consists of various natural fatty acids and residual confounders, rather than a single nutrient—is a potential factor to take into consideration to achieve a reduction in the risks of diabetes.

Excess cholesterol accumulation can lead to insulin resistance, which is closely associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D)13. Previous studies have demonstrated that the risk of T2D increases with elevated plasma SFAs content. Substituting SFAs with MUFAs in the diet may reduce the risk of T2D14. However, cholesterol and saturated fatty acids are essential nutrients for the human body, and our daily intake is generally not as elevated as in the experimental model. The body requires blood cholesterol for the synthesis of certain important hormones and substances, while saturated fatty acids contribute to the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and the enhancement of immunity. Several studies have indicated that moderate consumption of lard or saturated fatty acids does not adversely affect glycolipid metabolism15. It is noteworthy that the proportion of fatty acids in lard is relatively balanced, under controlled intake conditions, lard or a combination of lard and vegetable oil can reduce adipose tissue fat deposition and hepatic fat accumulation compared with vegetable oil alone16,17,18. Nowadays, modern dietary guidelines universally propose precise nutrition, which suggests improving or decreasing levels of certain isolated nutrients. Judging a food or a diet pattern as harmful or beneficial based on a single-nutrient component focus is limited, and outcomes produced by such studies are usually biased, extreme, simplistic, and paradoxical. For instance, early studies claimed that SFAs and cholesterol seemed to increase the risks of type 2 diabetes. Actually, SFAs are heterogeneous—odd-chain and even-chain, or short-chain, medium-chain, long-chain, and very-long-chain—and the physiological effects of each single SFA are dissimilar. The concentrations of medium-chain fatty acids and odd-chain fatty acids in lard are higher than those in soybean oil and canola oil19. Experimental evidence demonstrated that even-chain SFAs (e.g., 14:0, 16:0) have harmful effects in vitro, whereas odd-chain (e.g., 15:0, 17:0) and very-long-chain (20:0–24:0) SFAs appear to have more metabolic benefits20. This could explain why many observational studies suggest that most SFAs have a neutral effect on health.

Lard is composed of ~90% fat, with a fatty acid composition ratio of SFAs, MUFAs, and PUFAs estimated at 42:45:10. Furthermore, it contains a minor proportion of cholesterol, ~0.1%, as well as fat-soluble vitamins21. Based on the causation (bias) regarding dietary SFAs and cholesterol, lard and other foods rich in these components (such as butter and palm oil) are restricted in most modern dietary guidelines. For instance, in the case of lard, the predominant fatty acid is polyunsaturated fatty acid, with the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids exceeding that of saturated fatty acids. According to the recommendations of domestic and foreign dietary guidelines for the total amount of saturated fat control per day, it is about 50 g when converted into lard10. According to the Chinese Nutrition Society and our previous study, lard is preferable to vegetable oil if daily fat intake stays under 30g22. Moreover, lard exhibits a higher smoke point than vegetable oil, thereby decreasing the probability of trans-fatty acid formation and making it more appropriate for high-temperature cooking techniques, such as stir-frying. Lard exhibits a distinctive triglyceride structure characterized by the esterification of palmitic acid at the Sn-2 position. This specific structural configuration bears resemblance to that of milk fat and is of significant importance in the processes of lipid digestion and absorption12. Intriguingly, even-chain SFAs and cholesterol in blood are commonly endogenously synthesized in the liver, rather than directly ingested from foods23,24, and the overall combination of food components—including all residual confounders—generally together produce synergistic effects on health.

Lard contains a balanced composition of saturated and monounsaturated fats, which have been associated with a decreased risk of heart disease. Research indicates that lard is abundant in saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, which may enhance insulin sensitivity and thereby aid in the regulation of blood glucose levels25. And the predominant MUFA in lard is oleic acid (OA), a fatty acid essential for cardiac health26. OA can reverse palmitic acid-induced insulin resistance in human HepG2 cells via the reactive oxygen species/JUN Pathway27. Furthermore, certain fatty acid components in lard, such as palmitic acid, have been found to further improve glucose metabolism by regulating fatty acid synthesis and oxidation pathways28. The combination of lard and vegetable oil results in a fatty acid composition with approximately equal proportions of SFA, MUFAs, and PUFAs. Our Previous research has elucidated that this specific oil mixture demonstrates a notable anti-obesity effect. This effect is attributed to its capacity to enhance lipid metabolism through the promotion of bile acid conjugation with taurine and glycine, subsequently activating the G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 117. On the other hand, except for without any trans-fatty acid, lard is rich in vitamin D29, which have been proved that it could protect β cells and curbs type 2 diabetes progression30. And our study shows that the lard and soybean oil mixture can alleviate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice17.

Furthermore, while researchers focused on dietary fat, evidence of the effect that modest lard intake is negatively associated with health is lacking. Most experimental studies used lard as a reagent to model high-fat diet-induced obesity or diabetes, generally feeding the modeling animals a high dose of fat, and rarely focusing on the metabolic effects of moderate dietary lard intake31,32. These appear to further aggravate the potential bias regarding dietary lard.

Conclusions

Taking the present results and published data into comprehensive consideration, if no effective intervention actions are taken, the incidence of diabetes will grow sharply in those countries and areas with lard-excluding dietary patterns. In countries characterized by rapid economic development, represented by China, keeping lard and pork out of kitchens may be a causal risk factor for the constantly increasing incidence of diabetes. We hope that this article encourages scientists and guideline makers to focus more on the benefits and special value to health of appropriate lard intake, and to reveal the regular patterns and mechanisms of it.

Responses