Karma economies for sustainable urban mobility – a fair approach to public good value pricing

Introduction

Public goods are resources available to all in society without restriction. The tragedy of the commons describes a situation, in which insufficient incentives in combination with self-interested individuals results in overuse, depletion, or damage of these public goods (even this is not in anyone’s long-term interest)1,2. Road networks and congestion can be considered exemplifying this problem3. Road networks attract many users, as they enable individual mobility, and provide accessibility to many useful destinations for work, shopping, education, socialization, or recreation purposes. Roads provide a diminishing utility for a growing number of users; if too many vehicles enter the network, traffic slows down and congestion arises. Congestion is a global issue, with consequences for drivers, residents, and society. Noise, air pollution, and security incidents, affect the living quality and health of residents. A significant amount of a driver’s life-time is wasted in traffic jams. Wasted consumption of energy and time cause financial damages to the economy, and avoidable emissions contribute to global warming and the climate change4,5,6.

Governmental intervention and regulation can help to solve congestion, by aligning individual incentives with the collective good and keeping consumption of the road infrastructure at sustainable levels. Access-restricting regulations involve the establishment of property rights, rationing (capping)7, cap-and-trade mechanisms8, taxation9, or value pricing10. A broad variety of economic instruments have been proposed to cope with the issue of congestion and can be used to control traffic demand and supply. Traffic demand management employs road pricing, such as tolled bridges and tunnels, urban congestion pricing, and tolled highway lanes11. Besides, examples to control the supply can be found in license plate rationing, tradeable credit schemes, and mobility permits12,13. These economic instruments can be designed and implemented in conjunction with other traffic management strategies, such as infrastructure improvements, public transport expansion and investments, traffic signal optimization, and information provision, to create a comprehensive and effective transportation system.

Economic instruments introduce monetary, market-based incentive mechanisms for the allocation of resources. Despite potential benefits for solving the socially relevant question of traffic congestion, economic instruments appear to enjoy little support outside academia. Limited social and political support has caused many proposed schemes to be abandoned before implementation, or postponed for an undefined time14. Reasons for the lack of public acceptance include lack of trust in government, perceived severity of congestion, organized opposition by drivers, and equity concerns15. Often, the public is not convinced about the severity of congestion and the need for the implementation of economic instruments, doubts technological feasibility, or is concerned with privacy issues16,17. Moreover, drivers refuse to be charged for something they feel is not their fault and ought to be free to them14. In addition to that, people made significant decisions related to high personal investments, such as buying a car, choosing where to work, and deciding where to live. These decisions were based on costs and travel times for commuting in advance. This sunk cost fallacy often provokes organized opposition from drivers18. Finally, economic instruments can raise equity concerns; they may disproportionately benefit higher-income travellers who can afford tolls, while imposing additional costs on lower-income commuters with fewer transportation alternatives. Following question therefore arises: How can traffic demand be reduced in a socially-feasible, equitable way that is accepted by the public?

Monetary markets are not always the right tool for resource allocation, and in many contexts, the use of money is not desired, socially accepted, considered ethical, or even permitted. Therefore, a growing branch of literature is concerned with artificial currencies19, which represent non-monetary markets and resource allocation mechanisms. For isolated, single-stage resource allocation problems, extensive work on non-monetary matching and combinatorial assignment problems has been conducted20,21,22,23,24,25. For repeated resource allocation problems, there are few works on non-monetary market mechanisms yet, among which Karma has evolved as an important narrative26.

Karma employs a currency different from money; it can only be gained by producing and only be lost by consuming a specific resource. It is a resource-inherent, non-monetary, non-tradeable, artificial currency for prosumer resources (produced and consumed by market participants alike). As a non-monetary mechanism, Karma complements monetary markets and provides attractive properties. For example, it is fairness-enhancing, near incentive-compatible, and robust towards population heterogeneity27,28,29. Due to its design, one can consider Karma as playing against one’s future self, as the only way to consume is to put in effort and produce first, and future needs must be traded off against present needs when consuming. Last but not least, Karma is reported to not only concern the efficiency and fairness of resource allocation but also to lead to a decrease in resource scarcity in peer-to-peer markets30,31,32,33.

Using the example of congestion pricing, let us discuss Karma34, where vehicles need to pay a surcharge for driving in the city. Due to the monetary disincentive, people will trade off their urgency to drive to the city and their willingness to pay. However, congestion pricing can be problematic, as equity issues emerge in a society with unequal distribution of economic power: the poorest will most likely not be able to afford the charge, and thus consume significantly less. Karma could make a difference here: not driving could be considered producing, and driving could be considered consuming the resource “right of driving to the city”. Instead of paying money as a congestion pricing tax, Karma points could be used. These Karma points cannot be bought, but only gained by not consuming. Therefore, Karma would create a balance between giving and taking, between using and not using the public good. This would force individuals not to trade off the price with other resources they could buy alternatively but to solely consider present versus future consumption of this specific resource. Moreover, the socio-economic contexts, such as income or wealth, and therefore the above-mentioned equity considerations, would not play a role anymore. Finally, contrary to monetary pricing, Karma would not impose additional financial costs on the society.

Karma and tradeable credit schemes have in common that they are both some forms of artificial currency used for paying for mobility resources. While Karma is a demand management strategy, tradeable credit schemes are a supply management strategy. Contrary to tradeable credit schemes, Karma is not tradeable. This can be especially useful in addressing the aforementioned equity issues with economic instruments in the context of traffic demand management, as poor individuals have no ability and incentive to sell their rights to others to be able to afford additional other resources that could be bought with money. Rather, Karma enforces individuals to act according to their mobility needs only, fully independent of their economic situations. This ultimately leads to an inclusive allocation of mobility resources to those in need, and not those able to afford to pay for them. Even though Karma is a non-tradeable currency, yet, Karma can be considered a market mechanism, as individuals’ actions affect each other, and prices in Karma depend on the market’s demand and supply.

The overall goal of this study is to demonstrate the potential of Karma to address the equity issues of economic instruments when coping with public goods. This work primarily follows two objectives: (i) to highlight the value proposition of Karma as a non-monetary resource allocation mechanism, and (ii) to equip the reader with the necessary tools and knowledge to successfully apply Karma in various contexts and domains. To achieve these objectives, we elaborate on the properties of Karma, provide guidance on the design of Karma mechanisms, outline a game-theoretic model of Karma as a dynamic population game, and present a software framework to model problems and predict user behaviour in Karma economies. In addition, we compare Karma economies with monetary markets in a case study on bridge tolling, to demonstrate its usefulness.

The contributions of this study are twofold. First, this study contributes to the economic discussion of traffic demand management by providing the perspective of non-monetary market mechanisms to explicitly address equity issues by introducing Karma as a feasible, alternative complement to monetary markets, and tradeable credit schemes. Second, this study contributes to the literature on Karma mechanisms, by providing a unifying framework of mechanism design elements, as well as a software library to efficiently simulate Karma economies. Ultimately, this work enables more systematic, reproducible research on Karma for resource allocation.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows. Section Literature Review summarizes related works on Karma, presents applications in transportation, highlights its value proposition, and presents mechanism design elements. Section Results presents the case study of a tolled bridge and the underlying assumptions we have made when comparing money with Karma, and analyses the results of comparing money and Karma markets. Section Discussion converses about the concept of Karma in depth, comparing it with monetary markets and tradeable credit schemes, elaborates on the underlying perspectives on fairness, highlights challenges and limitations of Karma, and blueprints the real-world implementation of Karma mechanisms at the example of congestion pricing. Section Methods outlines the modelling of Karma as a game, presents the software framework and outlines its usage in a simple computation example about auctions. Section Conclusions brings this work to an end, and outlines future research directions.

Literature review

Related works on Karma

Karma is a concept that emerged from the domain of filesharing35, enjoyed popularity as a technological component in blockchain applications, and gained prominence as an artificial, non-monetary currency in the literature of economics. As a resource allocation mechanism, Karma has been applied in a wide range of contexts, including file and computational resource sharing in peer-to-peer networks, allocation of transmission bandwidth in telecommunication networks, and distribution of food and organ donations26.

In the context of traffic demand management, pilot studies on Karma have investigated its potential use for high occupancy and priority toll lanes28,36, auction-controlled intersection management with fully connected vehicles27,29, and transportation modality pricing37,38.

When applied as a resource allocation mechanism, Karma can be described by a population of agents, where each agent ⋯

-

has a specific amount of Karma,

-

has a random, time-varying urgency (representing the agent’s cost when not getting a specific resource),

-

has an individual temporal consumption preference type (a discount factor, representing the subjective trade-off between consuming now versus later).

In a repeated, auction-like setup, agents are matched randomly in rounds to compete for a specific resource by bidding with Karma. Depending on their urgency, Karma balance, and consumption type, agents must determine an optimal bid to earn the resource when necessary, while accounting for potential future competitions in subsequent rounds.

Riehl et al.26 identifies mechanism design elements based on a systematic comparison of previous Karma applications. These mechanism design elements are outlined in Table 1 and cover three aspects of Karma mechanisms: currency, interaction, and transaction. As noted in many previous works, a major design complexity is choosing the right amount of Karma currency in circulation37,38,39,40. If there are too few currency units, there will be hoarding to save the scarce currency for very urgent situations to consume; if there are too many currency units, the value of a single currency unit is no longer sufficient to stimulate the provision of resources. In the case of a time-variant resource supply, dedicated amount control becomes necessary.

Value proposition of Karma

Karma has the potential to address the equity issues of economic instruments when coping with public goods. Governmental intervention in the context of public goods involves regulating access to them, so that consumption is limited to a sustainable amount. The access right to consuming the public good can be considered the resource of interest. This resource can be viewed as a prosumer resource, as each system participant can both produce and consume it. The allocation of this resource can be done by a central coordinator (i.e., the government) or a decentralized mechanism (i.e., the market). Monetary markets can cause equity issues, as resource consumption is linked to economic power, which is usually distributed unequally. Instead of monetary markets, artificial currency mechanisms such as Karma could be used for resource allocation.

Previous research has found that Karma provides useful features that distinguish it from money. Karma is fairness-enhancing, as the consumption of resources depends on urgency and previous behaviour, and not on economic power. Karma is able to approach levels of efficiency similar to centralized, efficiency-maximizing algorithms, while outperforming them in terms of fairness27,29,41. Karma has a direct approach towards utility. As Karma is resource-inherent, there is no other aspect besides the pure utility value of a specific resource for participants when bidding at auctions. Hence, Karma achieves high levels of incentive-compatibility29,42,43,44. In monetary markets, the readiness to pay prices not only depends on utility but also on economic power, and the comparison of values with other resources that could be bought alternatively for this price. Karma is of substantial value here, as it enables an intuitive, direct, utility-focused, comparison-free evaluation of a resource’s value. Rather than to trade-off resources against each other as in monetary mechanisms, Karma allows solely for the resource-specific trade-off between present and future needs. Moreover, Karma decreases the scarcity of resources, as it incentivises cooperative behaviour and contributions amongst a population of rational, selfish individuals. This happens, when resources are not provided by a central coordinator, but provided by prosumers themselves (e.g., services). The underlying incentive scheme of Karma can cause significant increases in available resources; examples for this property include content sharing35,44,45, computational power in distributed computing applications35,44,45,46, a better mobile network coverage40,47,48,49,50,51, and more food and organ donations30,31,32,33.

Applied as an economic instrument in the context of traffic demand management, Karma mechanisms can be a valuable complement to monetary markets. Karma-driven economic instruments can overcome equity issues, and contribute to public acceptance and support for traffic demand management. Moreover, Karma does not create additional financial costs or taxes for users, which addresses the unwillingness to pay for road usage. Karma intrinsically embodies a fairness-enforcing scheme, balances consumption and production of resources, and ultimately controls a sustainable usage of public goods.

Results

In this work, we compare the distributional effects of money and Karma-based markets, deriving insights on when Karma works better than money. We use a case study related to New York, focusing on a static route choice, repeated resource allocation problem setup of bridge pricing for daily commuters.

Case study: the Manhattan borough & New York city

New York City is the most populous and most densely populated city in the United States of America, with an estimated population of 8.3 million people, and a land area of 1.2 square kilometres. New York City is located at the southern tip of New York State, and divided into five boroughs that are separated by rivers and the sea. Culturally and economically, it is one of the most vibrant cities, being home to financial institutions (Wall Street, New York Stock Exchange), and to headquarters of international corporations and organizations alike (United Nations, UNICEF). Due to its flourishing economy, New York and especially the borough Manhattan attract many visitors and commuters.

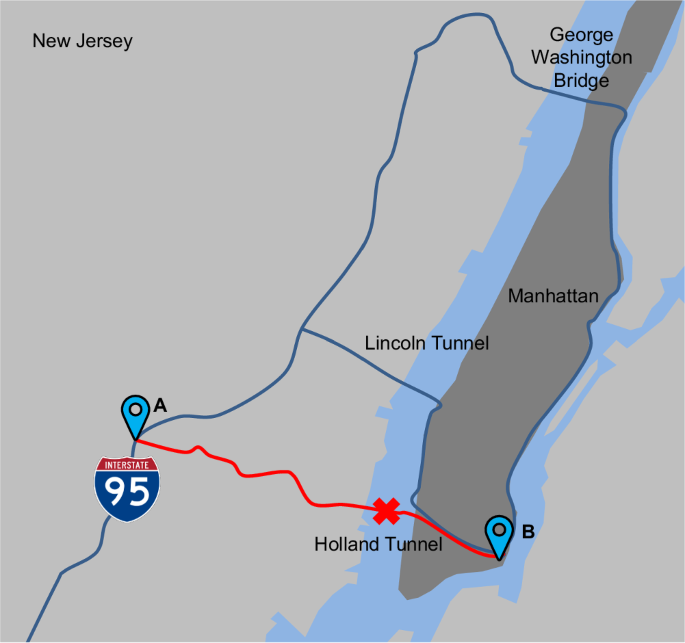

The neighbouring state of New Jersey is home to a large share of Manhattan’s workforce, with around 1.23 million people commuting daily. New Jersey and Manhattan are separated by the Hudson river. There are mainly three connections, drivers can use to cross the river: the Holland Tunnel (Interstate 78), the Lincoln Tunnel (Route 495), and the George Washington Bridge (Interstate 95), as shown in Fig. 1. Together, these three connections transport more than 493,000 vehicles per day. The Holland Tunnel consists of two tubes, has an operating speed of 56 km/h, a length of around 2.5 km, 9 lanes, and transports around 89,792 vehicles per day. The Lincoln Tunnel consists of three tubes, has an operating speed of 56 km/h, a length of around 2.4 km, 6 lanes, and transports around 112,995 vehicles per day. The George Washington Bridge consists of two decks (levels), has an operating speed of 72 km/h, a length of around 1.4 km, 14 lanes, and transports around 289,827 vehicles per day, making it the world’s busiest vehicular bridge. The connections are separated by 4,37 km and 10.87 km respectively52.

Manhattan attracts a large workforce from the neighbouring state of New Jersey, with commuters travelling via Interstate 95. The commuters can choose between Holland Tunnel, Lincoln Tunnel, and George Washington Bridge, to cross the Hudson river. In this case study, we explore the distributional effects of pricing the Lincoln tunnel, assuming the Holland Tunnel is closed and the traffic must distribute across the remaining two routes.

Currently, all bridges and tunnels in New York city follow a unified toll rate scheme by the New York Port authority, with prices per vehicle types, and time (on- and off-peak hours). The tolls are collected when entering New York, and not when entering New Jersey. Special discounts apply for taxis, or ride-sharing vehicles. Normal passenger vehicles pay between $13.38 and $15.38 (according to New York Port Authority, see 2024 Toll Rates https://www.panynj.gov/bridges-tunnels/en/tolls.html).

Unfortunately, New York is not only known as an attractive city, but also is it known as the city with the worst traffic in America. Vehicles spent an average of 154 seconds per kilometre driving in New York City (at an average speed 20 km/h) during rush hour. This sums up to 112 wasted hours per year and vehicle due to congestion (see the TomTom Traffic Index Ranking 2023 https://www.tomtom.com/traffic-index/ranking/?country=US for reference). Constructions, planned maintenance, scheduled overnight closures, and security incidents regularly cause the closure of these important bottlenecks.

In this case study, let us discuss static road pricing with monetary markets and Karma schemes for a scenario, where only two of the three passages are available. Let us assume that there is a fire hazard due to an accident in the Holland Tunnel, and that the tunnel is blocked for a week. Driving from A to B in our case study map (Fig. 1) would be around 26.55 kilometres (35 min free flow) via the Lincoln Tunnel, and 49.89 kilometres (40 min free flow) via the George Washington Bridge. Before closure, it was only around 17.38 kilometres (24 min free flow) via the Holland Tunnel. The traffic that came from Interstate 95 and used the Holland Tunnel, will divert to the next closest passage nearby: the Lincoln Tunnel. As a consequence, the Lincoln Tunnel faces congestion. Therefore, the New York City Port Authority decides to price the Lincoln Tunnel higher, and to stop charging for the George Washington Bridge. Doing so, the authority aims to distribute the additional traffic more efficiently between the two connections. In order to mitigate congestion, the authority will choose a price that minimizes the total travel time. We will compare the effects of road pricing between monetary markets and Karma markets.

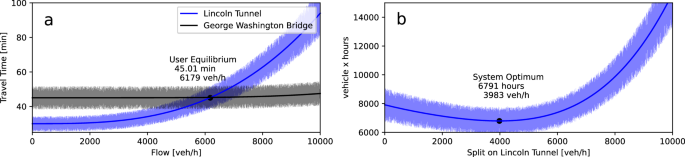

Figure 2 depicts the travel time model. We assume a traffic flow of 10,000 veh/h, which is split across the two routes. While the Lincoln Tunnel has a shorter travel time upfront, it gets congested quickly, and after 6000 veh/h it is much slower compared to the alternative route. The route via George Washington Bridge offers slower travel times, but higher capacity and less congestion and delays for even higher flows. From a system-optimal point of view, a minimum total travel time of 6791 vehicle hours (40.75 min average travel time) can be achieved, if the total flow (10,000 veh/h) splits to 3983 veh/h on the Lincoln route and 6017 veh/h on the George Washington route. Unfortunately, rational (selfish) individuals would optimize their individual outcome, leading to a user equilibrium (Wardrop equilibrium) at a split of 6169 veh/h on the Lincoln Tunnel, as there is no way to improve one’s individual outcome by changing anymore. The split at the user equilibrium (45.01 min average travel time) causes 4.26 min of additional travel time to every vehicle on average. With the right pricing of the Lincoln Tunnel, the total travel time could be reduced by almost 10%.

The travel times per route (a) depend on the traffic (flow) on each route. While the Lincoln Tunnel is a faster route in general, it reacts more sensitively to higher traffic, and becomes much slower due to congestion. The George Washington Bridge is a slower route, but has a higher capacity and therefore does not react to increased traffic flows. From a system perspective, the optimal traffic flow split can be achieved when the total travel time (vehicle hours) is minimized (b), resulting in approximately 3983 veh/h on the tunnel route, and the remainder via the bridge. However, rational individuals seeking to achieve the best outcome for themselves, as a consequence lead to a tunnel usage (Wardrop equilibrium) at which the travel times of both routes are equal. As a result, the selfish behaviour of rational individuals causes an additional 4.26 min of travel time per vehicle on average.

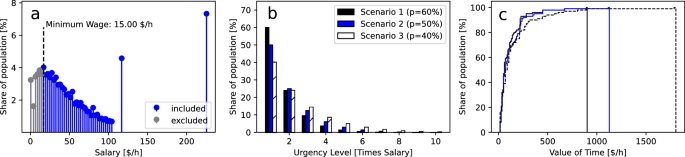

Figure 3 depicts the population urgency model. We model the population with ten urgency levels (1–10), where the urgency levels are assumed to be randomly-geometrically distributed in three different scenarios (p = 0.6, p = 0.5, p = 0.4). The n-th urgency level represents delay costs of n times the hourly wage, which is considered the value of time (VOT). An hourly salary based on the salary distribution of New York City (as reported in the 2022 U.S. Census (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Household_income_in_the_United_States#Distribution%20_of_household_incom)) is assumed.

Combining salary (a) and urgency distribution (b) for three different scenarios results in a value of time (VOT) distribution (c) that can be used to analyse the distributional effects using monetary road pricing. The urgency of individuals represents their willingness to pay n-times its salary for using the Lincoln Tunnel. We assume three geometrically-distributed urgency scenarios for this investigation.

Problem specification

Let us assume, that a population of commuters decides at the beginning of every day, whether they want to conduct their daily commute with their car via the Lincoln or the George Washington route. Depending on their urgency, commuters are willing to pay more or less. Let us further assume that the system is in a user equilibrium state, meaning the usage of roads and expected travel times are similar and known to all drivers.

For monetary markets, we calculate the user equilibrium following53; when drivers choose between taking the Lincoln Tunnel or the George Washington Bridge route they will minimize their costs. Each driver experiences three types of costs: for paying the fee if using Lincoln, paying fuel, and delay costs based on their VOT. We assume an average vehicle consumption of 6.5 l/100km (36 mpg), and a fuel price of 0.96 $/l. The numbers originate from reports published in 2021 by the U.S. Secretary of Transportation on the average fleet fuel consumption (https://edition.cnn.com/2022/04/01/energy/fuel-economy-rules/index.html) and the average fuel price (https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/gasoline-prices).

For Karma markets, we assume pairwise auctions between exactly two consumers, where each day, all consumers of the population are attending exactly one auction. The auctions are first price auctions, where the highest bid is paid to the society. The bidder wins the auction and needs to pay his bid, if his bid (the action) is above a certain (centrally-defined) Karma threshold price and the highest bid of the two auction participants. As bids are discrete integer values, but Karma threshold prices are continuous, winning the auction is modelled stochastically. Imagine an auction with two agents, bidding 3 and 4, and a threshold price of 4.2. Then this means that the agent with bid 4 receives the resource with a chance of 20%. Imagine an auction with two agents, bidding 3 and 4, and a threshold price of 3.5. Then this means that the agent with bid 4 receives the resource with a chance of 100%. The bid is paid to the society, meaning that at the end of each day, the winning bids from all auctions are collected, and then equally distributed across every member of the population (including the winners). The sum of all paid bids is distributed evenly as integer where possible, the rest is randomly distributed via a lottery. For example, in a population with 100 individuals, the sum of bids is 132. In this case, every individual receives one Karma point, and the remaining 32 Karma points are distributed point by point to randomly drawn individuals with replacement (it is possible that an individual is drawn multiple times). Users earn Karma by the bids they receive through the payments to the society. If they bid low or loose their auctions for multiple days, they accumulate Karma points over time, which enables them to bid higher when necessary for them.

One further assumption is, that all agents have an equal, temporal preference type with a discount factor of 0.85 (following previous studies). This temporal preference represents how much agents trade off future costs (rewards) over present costs (rewards). A discount factor of 0 would translate to completely neglecting any future costs, while 1 would translate to completely neglecting any present costs.

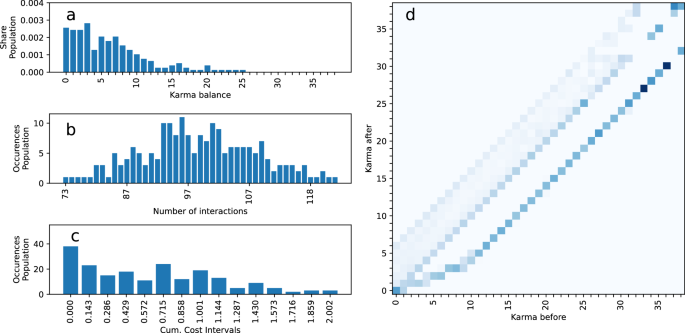

The consumer population is initiated with an average budget of 10 Karma points per individual, and the costs are modelled similar to the monetary market.

How prices affect consumer behaviour

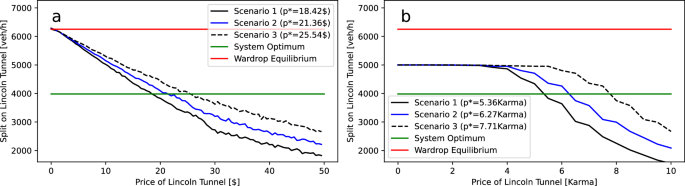

Figure 4a shows how different prices for the Lincoln Tunnel will affect the consumer behaviour in monetary markets. Without the presence of pricing, the user equilibrium lies at the Wardrop equilibrium (around 60% will take the Lincoln Tunnel). For an increasing price, the demand drops. For a price of $18.42, the user equilibrium lies exactly at the system optimum in scenario 1 ($21.36 and $25.54 for the other two scenarios). Similarly, a price in Karma Markets can reduce consumption, as shown in Fig. 4b. Without the presence of pricing, the highest-bid auctions will result in 50% of the population winning, as the market is modelled with exactly two randomly chosen participants per round. For a price of around 5.36 Karma, the user equilibrium can be controlled to sustainable levels as well in scenario 1 (6.27 Karma and 7.71 Karma for the other two scenarios).

a Increasing monetary prices incentivises the population of rational individuals to transition from the Wardrop Equilibrium towards the system optimum for a price of around $20–30. b Increasing minimum bids (prices) in Karma auctions leads to the migration of the Stationary Nash Equilibrium from 50% using the tunnel route to a system-optimal traffic flow split for a threshold between 5 and 8 Karma points (depending on the scenario).

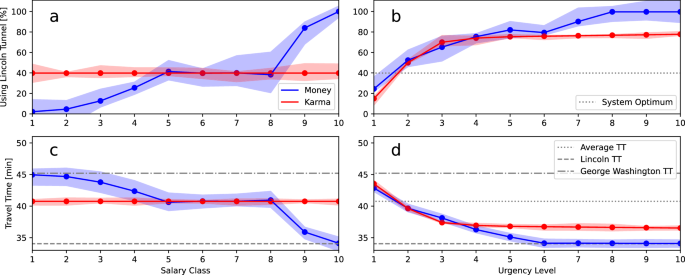

Figure 5 shows the share of consumers and travel times across different incomes and urgencies at the optimal price for scenario 1. Monetary markets enable consumers with higher incomes (higher salary levels) to use the Lincoln Tunnel, and to thus achieve significantly lower travel times. For instance, only ~20% of the consumers at the lower end of income are willing (or able) to pay for using the Lincoln Tunnel, while ~95% of consumers at the upper end of income are willing to pay for usage. Therefore, consumers with lower income have a noticeably higher travel time (~45 min) when compared with those of higher incomes (~34 min). These results exemplify the equity issues related to road pricing using monetary markets. Even though the pricing mechanism allows for achieving more efficient usage of the road infrastructure, it embodies the discrimination based on income, which is unevenly distributed across consumers. Contrary to that, we can observe Karma markets are completely indifferent to the income of consumers, as Karma follows its own, non-monetary logic. In Karma markets, 39.83% of all consumers, regardless of salary, will get access to the Lincoln Tunnel, and therefore achieve an average travel time of 40.75 min.

When optimally pricing the tunnel route with monetary mechanisms, individuals with higher incomes (salary class) experience significantly shorter travel times (c), as they can afford to access the faster route more often (a). When pricing with Karma mechanisms, access to the faster route and travel times are not related to the individuals’ income. With regard to the urgency levels, it can be observed for both mechanisms that individuals with higher urgency experience shorter travel times (d). In monetary mechanisms, individuals of very high urgency levels (starting from level 6) almost all access the faster route (b), while in Karma mechanisms, this is not the case. (The figures are plotted at the optimum travel split for scenario 1).

Karma allocates resources by addressing the needs of consumers

With regard to different levels of urgency, we find monetary markets guarantee access to the resource of interest to the highest levels of urgency (almost 100%), while only ~22% of consumers of lower urgency use the tunnel. Compared to money, the Karma mechanism deviates slightly; in the lowest urgency level 1, ~17% (so ~5% less) of the consumers get access to the tunnel, and at urgency level 3, ~70% (so ~5% more) of the consumers can access the tunnel. For higher levels of urgency, the Karma mechanism only guarantees ~75% (25% less) of the consumers access to the tunnel. At first sight, these results might imply that Karma does not align as well with the urgencies of consumers as money does. However, one must take into account that most consumers are in the lower urgency regimes (e.g., 95% of consumers with urgency less than level 5).

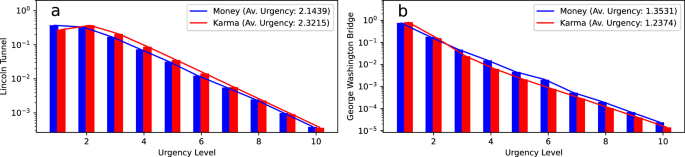

Therefore, we have analysed the distribution of urgency levels within the preferred route (Lincoln Tunnel) and the alternative route (George Washington Bridge), as shown in Fig. 6. The results show that the Karma mechanism leads to a situation where consumers of higher urgency are present in the Lincoln Tunnel, and consumers of lower urgency are present on the George Washington Bridge when compared with the monetary market. The Karma mechanism achieves an average urgency level of 2.32 in the Lincoln Tunnel (2.14 for money), and an average urgency level of 1.24 on the George Washington Bridge (1.35 for money).

The urgency level distribution of individuals (conditional probability) on both routes reveals that Karma achieves a greater alignment with needs than money does (higher resp. lower average urgency level on faster resp. slower route). On the faster Lincoln route (a), a higher average urgency level of drivers can be observed for the Karma resource allocation mechanism (when compared with monetary market mechanisms). Similarly, on the slower George Washington Bridge route (b), a lower average urgency level of drivers can be observed. (The figures are plotted at the optimum travel split for scenario 1).

Next, we analysed the costs and benefits of the road pricing strategy (for scenario 1). Table 2 contrasts resource usage, travel times, and cost breakdown for a situation where there is no pricing, where pricing with monetary markets is applied, and where pricing with Karma mechanisms is applied. Due to the introduction of pricing, resource usage can be reduced and therefore total travel time (and average travel time) can be reduced to a possible minimum. The cost breakdown reveals that the total financial costs per user, which consist of fuel costs, fees for the usage of the Lincoln Tunnel, and travel time costs (due to the VOT), can be reduced from $89.03 (unpriced) down to $81.20 (9% less). Thus, controlling access to the resource yields significant improvements for the drivers. While the fuel costs increase only slightly from $2.19 up to $2.53 (as more consumers drive the longer route via the George Washington Bridge), the pricing introduces financial fee costs in the case of monetary markets of $7.33 on average to the consumer. Karma has an advantage here, as no additional financial costs due to fees are generated. With regard to the costs due to travel times (VOT), we can observe that monetary markets can achieve stronger cost reductions from $86.84 down to $71.97 (17% less), as the money mechanism takes salaries and VOTs into account. Au contraire, Karma focuses on consumer needs (urgencies) only, and hence achieves solely 9% travel time cost reductions. Essentially, Karma and money both yield improvements when compared to the unpriced situation, with almost similar total cost improvements per user. The cost reductions from the monetary mechanism originate from a better alignment with the VOTs, at the cost of an additional fee, while the cost reductions from the Karma mechanism originate from a better alignment with the urgencies.

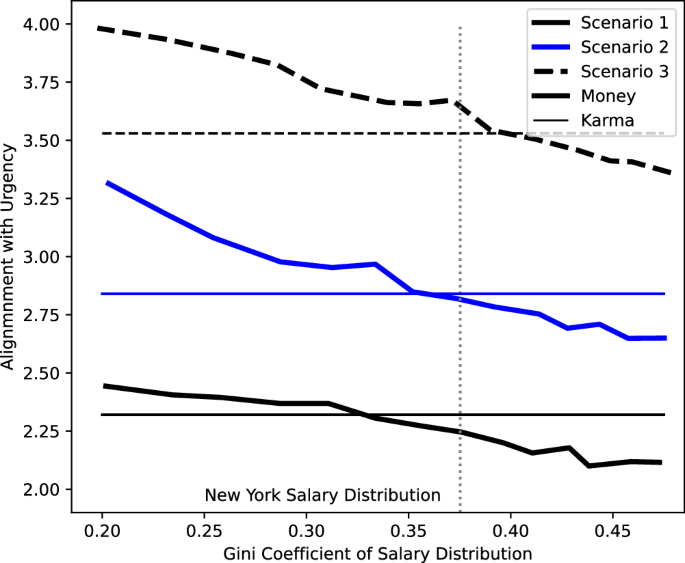

When Karma outperforms money

Finally, we have tried to better understand when Karma outperforms money. A major determinant of the distributional effects of the monetary mechanism is the distribution of financial power. Therefore, we sampled synthetic salary distributions with different levels of evenness measured by the Gini coefficient. The Gini coefficient of the assumed salary distribution of New York from the case study lies around 0.375. We generated salary distributions with Gini coefficients between 0.20 and 0.50, as most nations possess income distributions in that range. We then determined optimal prices to achieve system-optimal resource usage of the Lincoln Tunnel, and quantified the average urgency levels of consumers in the Lincoln Tunnel as a measure for how well the mechanism allocates resources and how strongly it is aligned with the consumer needs. The results for the three different scenarios are shown in Fig. 7, where alignment with needs (urgency) is measured as the average urgency level in the Lincoln Tunnel.

The superiority of Karma over money in terms of alignment with needs depends on the distribution of salaries. At a certain level of inequality in the income distribution, Karma performs better than money (Gini coefficient above ~ 0.35).

In societies with more even distributions (smaller Gini coefficients), monetary markets can achieve a larger alignment with the consumer needs. The larger the inequalities in financial power become, the less alignment with consumer needs can be achieved. The Karma mechanism, instead, does not react sensitively to the salary distribution. The superiority of Karma over money depends on the urgency distribution as well. In our case study, it turns out that the Karma mechanism works better than money for scenarios 1 and 2. In the fictional scenario 3, however, when urgency regimes become more evenly distributed, the Karma mechanism is slightly worse. In scenario 1, less than 5% of the consumer population is urgent enough to be willing to pay more than three times their hourly salary in exchange for the same amount of time, while in scenario 3 it is already 30%, which can be considered to occur rarely in practice.

Summary of findings

To summarize, Karma is a fair and efficient resource allocation mechanism that has the potential to address the equity issues of economic instruments when coping with public goods. The results of the case study indicate that, similar to money, Karma can be used as a resource pricing mechanism to control the user equilibrium to sustainable levels of consumption. Contrary to money, Karma embodies fairness, as it does not discriminate based on financial power (income), but orients resource allocation on the urgency of consumers. Karma is an efficient and robust resource allocation mechanism that works independently of the distribution of financial power in a society. The results indicate that Karma achieves a resource allocation that is better aligned with the urgencies of consumers than money does. This is especially the case for societies with higher inequalities in financial power. Furthermore, Karma pricing does not impose additional costs on the users and generates significant improvements both in travel times and total costs per user.

Discussion

In this section, we critically and comparatively discuss Karma in the context of congestion pricing and tradeable credit schemes, elaborate on the underlying fairness concept of Karma, highlight challenges with Karma mechanisms related to inactive users and market liquidity, how to solve them, and outline a blueprint for real-world implementation.

First, let us discuss Karma in the context of congestion pricing, and tradeable credit schemes. Urban traffic congestion is a pertinent issue, with dramatic consequences such as wasted lifetime and impaired life quality, pollution of the city population and environment with emissions and noise, wasted fuel and economic damages, and effects on public health due to stress and emissions. Traffic demand management aims to decrease traffic flow to solve congestion. This is achieved by incentive mechanisms that change the behaviour of consumers. Most people agree that it is necessary to reduce the consumption of road transportation resources in order to improve the livability of cities, and to achieve environmental goals. Yet, traffic demand management experiences significant public resistance. Even though most people acknowledge congestion is a severe problem, only a few cities (Singapore, London, Stockholm, Milan, Gothenburg, and New York) worldwide implement traffic demand management measures such as congestion pricing. To drive the real-world implementation of traffic demand management, these equity issues must be sufficiently addressed, in order to gain public acceptance in political, public decision-making processes. The first step, therefore, is to better understand the public resistance against congestion pricing. Equity issues and additional imposed costs are the major reason for public resistance. If access to roads is restricted, people can drive less often. However, driving often is the only affordable and accessible means of transportation in cities. Public transportation is often insufficiently available, inconvenient, and expensive. People’s concern is that monetary instruments will cause systematic inequities and discrimination, leading to situations where those who cannot afford will drive less, while others just continue their current consumption behaviour. However, mobility is an essential component in today’s life, for accessing better work opportunities, education facilities, and recreation. A systematic, unequal restriction to mobility resources therefore harbours the threat of systematically reproducing and reinforcing existing societal inequalities.

The motivation for our research on Karma was to address these equity issues. Is it possible to develop a form of congestion pricing that is more equitable? Similarly, tradeable credit schemes were extensively discussed in the literature to answer this question. Tradeable credit schemes (also termed tradeable mobility permits, or mobility credits) are allowances that limit the traffic demand and that grant holders the right to drive into the city13. Similar to conventional congestion pricing, tradeable credit schemes do not enjoy large public support, as survey studies have found. While tradeable credit schemes seem a popular alternative to conventional congestion pricing and license plate rationing, they do not enjoy support when compared with unrestricted access. People are concerned with the restriction of their freedom, and rather choose freedom over tradeable credit scheme systems. The acceptance depends furthermore on cultural, economic, and social contexts 54,55. A study shows that tradeable credit schemes might not sufficiently address equity issues, as especially people of lower income will significantly reduce their mobility consumption56. Furthermore, scholars raise additional concerns with tradeable credit schemes, such as the cognitive complexity of trading the allowances to actually benefit from the ability to trade the permits, as the the credit price is endogenously determined by the credit-trading behaviour57. Karma-based congestion pricing might be a significant improvement for these equity issues, as not only the poor but all users are equally forced to economize and reduce their consumption patterns. This would address the concerns of systematic inequality, systematic discrimination, and potentially achieve envy-freeness.

Second, let us discuss Karma in the context of fairness. Defining fairness is a complex philosophical question, and usually depends on cultural values, norms, and situational contexts58. Traffic demand management measures such as congestion pricing reduce demand (consumption) by using financial incentives. This usually faces public resistance due to equity issue concerns. Probably, the most useful definition of fairness is such one that enables us to win public acceptance. We must be convincing that the traffic demand management system we try to implement is fair to all. Some might argue Karma even decreases fairness. In conventional congestion pricing, or systems with tradeable credit schemes, users that urgently need the mobility resource can just buy it with money, while in Karma systems this would not be possible. In scenarios where there are permanent, large differences in the demand between users, Karma would fail to allocate resources efficiently in this vein, as users do not have the ability to buy the resource if necessary. Take work commuters as an example. Even though they are willing to pay more, they are not able to get more. From this perspective, taking the possibility to trade, buy, and sell rights using money seems to let users worse off only. This critical interpretation of congestion pricing with Karma probably advocates a definition of proportional fairness in the spirit of Aristotle58. According to this definition of fairness, the more you contribute, the more you should get. An implicit assumption of this interpretation is that everyone in need who is willing to access the mobility resource is able to buy the resource if necessary. As previous studies for both congestion pricing and tradeable credit schemes show, this is not necessarily the case. In the case of congestion pricing, many users might not be able to afford the congestion tax anymore. In case of tradeable mobility credits, users who would like to travel by car might rather sell their rights because they need the money more urgently. Moreover, one could question whether permanent, large differences in the demand between users are fair per se. Permanent differences in traffic demand might be the result of existing social inequalities that persist, perpetuate, reproduce, and reflect systematic inequalities imposed by the system. In the sense of the transportation justice movement59 one could argue that mobility accessibility is related to socio-economic, social mobility: (i) the poor cannot afford a car, and need to take public transport instead, (ii) because they take the public transport, they are disadvantaged and waste time, (iii) because they have less free time for recreation and education, they are less productive and impeded from getting a better job, higher income, and stay poor. Finally, we could ask whether there are more or less noble reasons to consume mobility resources. And even if we agree that commercial and commute related mobility should be prioritized over leisure related mobility, one of the major reasons for the congestion peak hours we observe in most cities is due to the daily commute. We argue that Karma increases fairness. In order to achieve less congestion, mobility resource consumption must be reduced; to put it simple we must drive less. With Karma markets, all users equally need to economize their budget, when considering on which days it is sufficiently urgent for them to drive and when not. Within monetary markets (including conventional congestion pricing and tradeable credit schemes), we systematically prioritize those who can afford, not necessarily those who are in need the most. Important to emphasize at the same time is, that Karma might not achieve fairness-optimal resource allocation or solves all problems, but rather can it be considered an improvement in terms of fairness when compared with unrestricted access, monetary congestion pricing, or tradeable credit schemes. Karma shifts the problem from “being able to afford” to “being able to produce” (i.e., not to consume). One could argue, that especially the parts of the population with a lower income often need to commute more often, as rents further away are more affordable, and often need to work in employments that do not provide flexibility in work time and location. This argumentation, however, focuses on the complexities that arise with restricting access and enforcing mobility demand reduction, and neglects the relative fairness-improvements that Karma has to offer when compared with monetary congestion pricing.

The question of fairness often relates to the question of economic welfare. When using monetary congestion pricing to reduce demand and therefore congestion, we cause a reallocation of a smaller amount of scarce mobility resources to a population of drivers. A monetary pricing mechanism might allocate the resources most efficiently, as the mechanism focuses on those who are willing to pay the most. In this sense, those who are willing to pay the most are those with the highest value of time, which is the product of their urgency level and their hourly salary. Furthermore, those who are willing to pay the most, are those that would experience the highest economic damage by being delayed. However, we argue that another perspective and definition of welfare might be necessary here, such one that focuses on needs rather than the value of time. We are convinced, that public acceptance towards traffic demand management using economic instruments could be enhanced, when considering everyone’s damage in time as equally important, meaning that the urgency level itself, rather than the value of time, is what we should consider as welfare measure. As shown by the results of this study, Karma achieves higher levels in that sense, as it focuses on needs only, independent of economic power. Assuming the time and needs of everyone as equally important (independent of their economic power) therefore democratizes demand reduction and increases acceptance.

Third, let us discuss the challenges with inactive users and market liquidity. A challenge with Karma mechanisms is the liquidity of the Karma market, meaning the right amount of Karma currency in circulation26,37,38,39,40. Two important aspects play a role in controlling liquidity: amount control, and strategies to cope with inactive users. First, controlling the amount of Karma, for example by a fixed amount of Karma per person, is crucial to ensure that there is no hoarding of Karma while also providing sufficient incentives to stimulate production and consumption. In the case of a time-variant number of users, a dedicated amount control is an important aspect to consider when designing Karma economies. Second, the activity of users plays an important role. In practice, population heterogeneity in temporal preferences and urgency processes will exist, causing significant permanent differences in urgencies. Inactive users who have very low urgencies and might never have an interest in consuming, harbour the threat of accumulating large amounts of Karma over time, reducing the liquidity of the market. Potential countermeasures to address these inactive users include strategies to limit the maximum amount of Karma a user can possess and redistribution of Karma using combinations of lotteries and auctions. Moreover, as discussed in the following elaboration on a real-world implementation, it might be useful to define minimum consumption rules for members of the Karma economy, and to systematically exclude those inactive users if they fail to comply.

Fourth, let us discuss a blueprint for a real-world implementation of a Karma economy. In a real-world context, various complexities need to be addressed when implementing a form of public good value pricing. The largest complexity is probably the varying number of users in the system. Similar to various propositions of tradeable credit schemes for congestion pricing, a combination of conventional monetary congestion pricing and equity-addressing instruments might be recommendable. Karma could serve as a flat rate or frequent user programme, as a complement to conventional monetary pricing for non-frequent, or foreign users. We envision two possible ways to enter the city by car. One component is using conventional congestion pricing, which could be applied to infrequent drivers, such as tourists or inactive drivers. The other component is a Karma-based congestion pricing, e.g., for recurrent, regular, and frequent users of the public good. One could start with a conventional congestion pricing with a sufficiently high cost, to incentivise regular users to join a Karma-based system. Joining the Karma-based system would require the drivers to stay for at least a certain period, and allows road usage only, when paid with Karma. Violating this requirement would result in “painful” fines. The right choice of a minimum membership duration and financial penalties could provide the right incentives not to switch too frequently between conventional congestion pricing and Karma mechanism, ensuring system compliance.

Methods

Game-theoretic formalism

In previous works, Karma was described primarilly in verbal terms, which impedes systematic, quantitative analysis. Modelling Karma as a game is useful, as it allows us to predict user behaviour and to simulate Karma economies as multi-agent systems26. In this section, we outline the game-theoretic formalism used for our software framework and explain how the agent behaviour can be predicted using the social state of the Stationary Nash Equilibrium for dynamic population games.

We define indexes as non-capitalized letters, e.g., i. We denote sets as calligraphic letters, e.g., ({mathcal{A}}). We denote scalars as non-capitalized, indexed letters, e.g., τi or ({u}_{i}^{t}). We denote functions as capitalized letters, with discrete arguments in square brackets and continuous arguments in round brackets, e.g., A[b](c) = d. We denote probabilistic functions as Greek letters with subscripts p, e.g., πp. We denote Pr(a∣b) to describe the conditional probability of an event a given b. Table 3 summarizes the notation used to describe the Karma game, and to model the resource allocation problem for the software framework.

Karma is as a repeated, stochastic, dynamic population Game, represented by a tupleG of parameters. (G=langle {mathcal{N}},{mathcal{T}},{mathcal{U}},{mathcal{K}},C,T,{Theta }_{p},{Omega }_{p},{Psi }_{p},{pi }_{p},{d}_{p}rangle)

In a Karma game, there is a population of n agents. For each point in time t (epoch) of the game, each agent i of the population (iin {mathcal{N}}={1,ldots ,n}) possesses a state consisting of a type τi, an urgency level ({u}_{i}^{t}), and a Karma balance ({k}_{i}^{t}ge 0,{k}_{i}^{t}in {mathcal{K}}).

During each epoch t, a subset of agents ({mathcal{J}}subset {mathcal{N}}) is encountering a competition e for a resource at hand (interaction). Each participating agent (jin {mathcal{J}}) during the encounter makes a decision based on its own type τj, urgency level ({u}_{j}^{t}), and Karma balance ({k}_{j}^{t}) independently of each other (as the state information of each agent is private, invisible to others) using the policy πp = Pr(a∣τ, u, k), and thus executes an action ({a}_{j}^{e} sim {pi }_{p}) during the encounter. As a result of the interaction there is an outcome ({o}_{j}^{e}) that determines how the resource is distributed for agent j (e.g., if it receives the resource). The outcome (resource allocation) affects the future states of the participating agents ({u}_{j}^{t+1},{k}_{j}^{t+1}forall jin J). The subset ({mathcal{J}}) is randomly and independently chosen from the population. In one epoch, there can be multiple interactions.

The agent type ({tau }_{i}in {mathcal{T}}) is time invariant and represents the agent’s type of temporal preference. The agent urgency level ({u}_{i}^{t}in {mathcal{U}}) determines the immediate costs (rewards) the agent experiences after the interaction of an encounter e by the outcome oe. The immediate cost an agent experiences is described by function C[u, o] that maps the urgency level and interaction outcome to immediate costs. The discount factor function T[τ] maps the temporal preference type to the discount factor. The discount factor (Tleft[tau right]in left{{mathbb{R}}| 0le Tleft[tau right] < 1right}) indicates how much the agent trades off future costs (rewards) over present costs (rewards). T[τ] = 0 would not consider future costs at all, while T[τ] = 1 would not consider present costs at all.

The possible actions ({a}_{j}^{e}) that the agent can choose from during the encounter e, is determined by its Karma balance ({a}_{j}^{e}in {{mathcal{A}}}_{j,e}={1ldots {k}_{j}}). The decision-making process of the agent to choose an action ({a}_{j}^{e}) from the set of possible actions ({{mathcal{A}}}_{j,e}) based on its own, private state τj, uj and kj is modelled by the policy πp. The policy πp is a probabilistic function that maps from a given private state to a probability distribution over actions πp[τj, uj, kj, aj] = Pr(aj∣τj, uj, kj).

The vector of actions of all participants ({{mathcal{B}}}_{e}={{a}_{j}^{e}forall jin {mathcal{J}}}) cause one outcome oe. The outcome oe is the vector of outcomes for each participant (j,{o}_{j}^{e}in {mathcal{O}}) that is determined by the probabilistic outcome function Θp. The outcome function ({Theta }_{p}[{o}_{e},{{mathcal{B}}}_{e}]=Pr({o}_{e}| {{mathcal{B}}}_{e})) maps from all participants’ actions in Be to the probability of different possible outcomes. The outcome oe of interaction e affects the participant’s next Karma balance ({k}_{j}^{t+1}) according to a probabilistic function Ωp, that represents the Karma transition probability, referred to as the Karma payment rule: ({Omega }_{p}[{k}_{j}^{t+1},{k}_{j}^{t},{{mathcal{B}}}_{e},{o}_{j}^{e}]=Pr({k}_{j}^{t+1}| {k}_{j}^{t},{{mathcal{B}}}_{e},{o}_{j}^{e})). The outcome oe of interaction e affects the agent’s next urgency level ({u}_{j}^{t+1}) according to a probabilistic transition function Ψp, that represents the urgency transition probability, respectively the τ-dependent urgency process: ({Psi }_{p}[tau ,{u}_{j}^{t+1},{u}_{j}^{t},{o}_{j}^{e}]=Pr({u}^{t+1}| {u}^{t},{o}_{j}^{e},tau )).

The distribution of types, urgency levels, and Karma balances in the population is the state distribution dp. dp[τ, u, k] describes the share of the population that has a specific type τ, urgency level u, and Karma balance k. Together with the policy, the state distribution is called the social state of the Karma game (πp, dp).

Depending on the chosen design element options for the aspect currency (see Table 1), further complexity can be added to this game. The amount of Karma per capita could be limited, or the total amount of Karma in circulation could be controlled according to a specific logic26. Furthermore, some form of Karma redistribution could take place, for example in the form of a lottery, or taxation.

Assumptions

Karma is a repeated, dynamic population game, as the Karma game is not played once but multiple times and the time is split into discrete epochs (rounds). As argued in previous works, a time horizon of at least multiple rounds is crucial to incentivise cooperation amongst selfish participants29,40,41,60,61. The formalism describes a stochastic game, as the state and state transitions of agents depend upon probabilities. Besides, the behaviour of agents, such as their bids or accepting resource provision requests, is modelled as a Markov decision process29,62. The formalism describes a population game, as the Karma mechanism aims to represent the strategic interplay in large societies of rational (selfish) agents (participants)62.

The Karma game makes certain assumptions in order to facilitate simulation and computation of the Stationary Nash Equilibrium. We will discuss these assumptions in the following:

-

The selection of participants for an interaction is randomly chosen from the population.

-

The Karma balance of each agent must be greater or equal to zero. There is no such thing as a Karma debt allowed.

-

The total amount of Karma in circulation remains constant over time.

-

The total amount of agents in the population remains constant over time.

-

The possible actions of an agent in an interaction solely depends on its Karma balance.

-

The decision-making process of agents to choose an action during an interaction solely depends on its own, private state (type, urgency, Karma), and not the states of others.

-

The decision-making process of agents to choose an action during an interaction solely depends on its own, current state, and not on its previous states.

-

The agents have an identical decision-making process by following the same, state-specific policy, assuming that the policy describes the best possible choice (optimum) for an egoistic, selfish, rationally acting agent.

Several, important implications follow from these assumptions, and are discussed in the following. Moreover, we provide guidance on how intelligent modelling can achieve Karma games of higher complexity, despite these restricting assumptions:

-

The selection of participants is not discriminatory in terms of agent type, urgency or Karma balance. This means that the probability to be selected in an interaction is proportional to the share in the distribution defined by d. There must be at least two participants selected. In certain contexts, it could be possible to have auctions with more than two participants, or even the whole population as in ref. 28.

-

A changing number of agents could be modelled by introducing a specific type and urgency, for agents that have no cost and no temporal preference, and thus will act in an interaction with the specific action type “no action” (e.g., refusing any action), so that they always result in a specific outcome type (not receive resource).

-

Only sealed bid auctions as a form of interaction are possible in the Karma system, as the state of agents is private to others and the system. This is particularly important, as it enables this form of decentralized, parsimonious control to work without a large overhead, and without the need to exchange any information except for the action. Of course this assumes that certain forms of smart contracts enforce all participants to act according to the set of possible actions.

-

An important assumption this model makes is that the agent’s decision-making is a Markov decision process chain, meaning that the decision-making of the agent at a specific stage only depends upon the agent’s current exogenous state and available actions, but not a history on past states or actions48.

-

The action of an agent must at least be the bid in a sealed bid auction, but can in addition include other actions. As an example, in ref. 28 the action is the bid and the decision when (timeslot) to start driving to work in the morning.

-

The outcome of the interaction oe is the vector of outcomes oe,j for each participant j. It could be modelled binary, where oe,j = 1 represents that participant j receives the resource, and oe,j = 0 represents that participant j does not receive the resource.

-

Multi-agent control systems often aim to find mechanisms to align selfish behaviour with global, societal goals. One can assume that a population of rational agents, be it human or autonomous, will always try to express a behaviour that will maximize their own, expected reward. Therefore, once proven that the policy is the optimal policy for a rational, selfish agent, we can conclude that all agents will follow the identical, state specific policy. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that each agent has the (cognitive) ability to identify the optimal policy, but this can be discussed in future research. Besides, one could assume an algorithmic bidding assistant for humans.

-

Agents can only possess and bid discrete amounts of Karma points. This is designed intentionally to facilitate the calculation of user behaviour (and the Stationary Nash Equilibrium), as each Karma budget captures a different bidding behaviour in the policy matrix. A continuous amount of Karma would result in an infinite number of cases to capture in the policy matrix, which is computationally not feasible. An approach to enable “more continuous” numbers is either to increase the average initial Karma per user, thus extending the dimensions of the matrices representing the Stationary Nash Equilibrium. Another approach could be, similar to what we did in the case study on New York, to model winning an auction with probabilistic conditions relating to a continuous price.

The interested reader is recommended to look in further modelling peculiarities in refs. 26,27,28,29,63.

Agent behaviour prediction

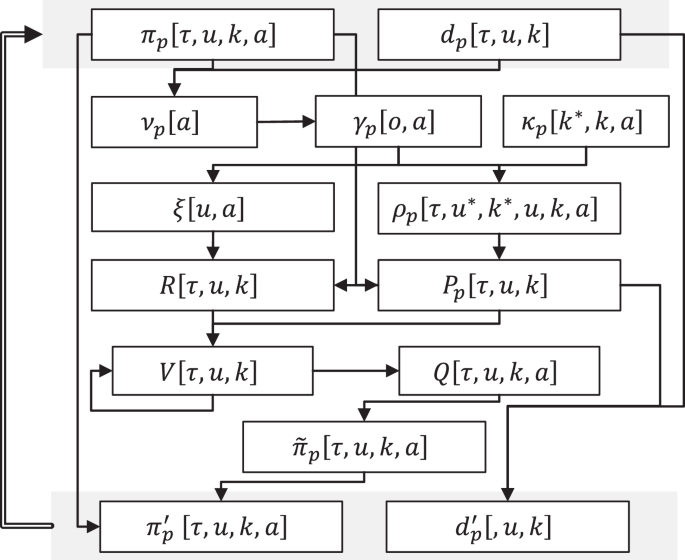

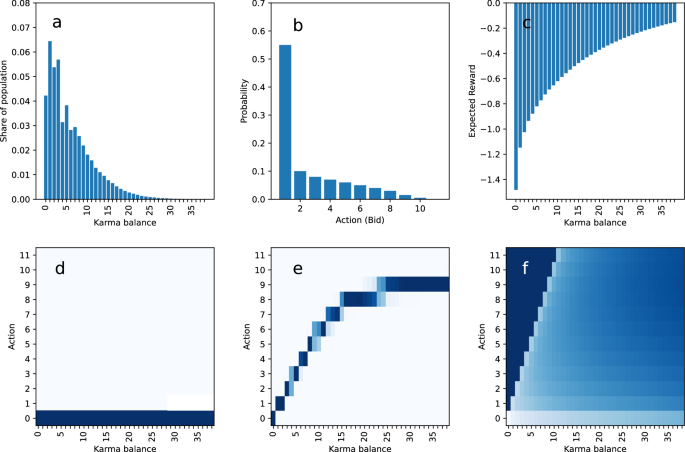

In order to simulate the Karma mechanism as a multi-agent system, it is of crucial importance to predict the behaviour πp[τ, u, k, a] of agents. Usually one assumes that each agent is rational and acts in its best self-interest, meaning an agent achieves the best possible outcome for itself. The rational behaviour of an agent is described by the optimal policy({pi }_{p}^{* }[tau ,u,k,a]). The Nash Equilibrium of a game describes the optimal policy, where no agent can improve its situation by deviating from the policy27,29,62. A population of rational agents following this optimal policy will lead to a stationary state distribution ({d}_{p}^{* }). For dynamic population games, the concept of a Stationary Nash Equilibrium describes the social state that consists of the optimal policy and stationary state distribution (({pi }_{p}^{* },{d}_{p}^{* })). At least one Stationary Nash Equilibrium for each Karma game is guaranteed to exist when the circulating amount of Karma is preserved27,29,62. The optimal social state can be calculated in an iterative way, as outlined in Fig. 8, by computing intermediate products.

The consumption behaviour of rational, selfish individuals in Karma economies can be predicted by calculating the Stationary Nash Equilibrium. The Stationary Nash Equilibrium29 consists of two components: (i) a probabilistic policy matrix πp that describes how much individuals would be willing to pay a, given their temporal preference type τ, urgency u, and Karma balance k; (ii) a population distribution dp that describes the share of the population with given τ, u, and k. The Stationary Nash Equilibrium can be calculated in an iterative process via intermediate results, as shown in this figure.

νp[a] represents the probability distribution of an average agent’s actions.

γp[o, a] represents the probability of an interaction outcome o for an agent given its action a.

κp[k*, k, a] represents the probability that an agent will have a Karma balance k* after the interaction, given a previous Karma balance k and action a. Depending on the logic defined in the Karma game for ({Omega }_{p}[{k}_{j}^{t+1},{k}_{j}^{t},{{mathcal{B}}}_{e},{o}_{j}^{e}]) the modelling of this function becomes a complex, non-trivial task. For instance, the Karma transition depends on whether the highest or second highest bid wins, whether the winner pays the bid to its peer or to the society, whether Karma redistribution takes place, etc.

ξ[u, a] represents the expected immediate costs an agent with urgency level u, Karma balance k experiences, when performing action a in an interaction.

ρp[τ, u*, k*, u, k, a] represents the probability that an agent of type τ will have an urgency level u* and Karma balance k* after the interaction, given a previous urgency level u, Karma balance k, and action a.

R[τ, u, k] represents the expected immediate cost for an agent of type τ, urgency level u, and Karma balance k that follows the policy πp[τ, u, k, a].

Pp[τ, u*, k*, u, k] represents the probability that an agent of type τ will have an urgency level u* and Karma balance k* after the interaction, given a previous urgency level u and Karma balance k, assuming that the agent follows the policy πp[τ, u, k, a].

V[τ, u, k] represents the expected infinite horizon cost for an agent of type τ, urgency level u and Karma balance k. V[τ, u, k] can be computed by the recursive, Bellman-equation as shown below, and is guaranteed to converge due to contraction-mapping.

Q[τ, u, k, a] is the single-stage deviation reward, when deviating from the current iteration’s policy. This intermediate computation product highlights where deviating from the current iteration’s policy is profitable and guides the process of improving the policy. In the Stationary Nash Equilibrium, Q would not deviate from the policy anymore, as it iteratively converges towards the final, optimal policy.

({widetilde{pi }}_{p}[tau ,u,k,a]) represents the perturbed best response policy. The hyper parameter λ controls for how strong (greedy) the single-stage deviation reward of this iteration should be taken into account when improving the policy.

Finally, the update of social state consists of two steps based on the computed, intermediate products P and ({widetilde{pi }}_{p}). Two hyper parameters, control the speed of change for the distribution (ϖ), and for the policy relative to the distribution (η).

In order to calculate the optimal social state at the Stationary Nash Equilibrium, previous works used iterative, heuristic and numeric optimization algorithms. Censi et al.27 suggests fixed point computation, momentum method and simulated annealing. Elokda et al.28,29,36 use evolutionary dynamics inspired optimization algorithms. Elokda41 employs the Smith protocol. The choice of a suitable optimization algorithm is important, as the state-space is large and the dynamics are rigid41. In this work, we compute the Stationary Nash Equilibrium employing an evolutionary dynamics inspired optimization algorithm29. The interested reader is highly recommended to review further optimization approaches in ref. 64, such as the Replicator-approach, Brown-von-Neumann-Nash, Smith, and the projection approach.

Software framework

In this work, we present a well-documented, open-source, software framework (Python, PEP8, GPL 3.0) to equip the reader with the tool-set to apply Karma as a resource allocation mechanism. It implements the game-theoretic formalism, allows for the computation of the Stationary Nash Equilibrium, provides a rich template library to model Karma, and enables the simulation of Karma as a multi-agent system.

To use the software, users will need to follow a three-step approach: (i) defining their Karma game (modelling), (ii) predicting the behaviour of market participants (optimization), and (iii) simulation of a multi-agent system Karma economy (simulation). In the following we will outline how the reader can model a resource allocation problem, how the optimal policy at the Stationary Nash Equilibrium can be computed using the optimization module, and finally how to simulate the resource allocation as a multi-agent system. For more information and details, please refer the to GitHub page and documentation.

First, let us discuss modelling. In order to model a Karma resource allocation problem with the software framework, the user needs to specify general parameters, logic functions (for simulation) and probabilistic functions (for optimization). The probabilistic functions need to be provided to capture how an individual agent would model reality and make decisions, in order to determine the optimal behaviour of a rational agent. The logic functions need to be defined in order to simulate the Karma game as a multi-agent system. The software framework offers a rich library of predefined templates and examples for the probabilistic and logic functions.

To begin with, the user needs to specify general parameters such as the average initial Karma, number of agents n, number of participants in an interaction (parallel {mathcal{J}}parallel), initial distribution dp[τ, u, k], set of temporal preferences ({mathcal{T}}), set of urgency levels ({mathcal{U}}), set of valid Karma balances ({mathcal{K}}), and set of possible interaction outcomes ({mathcal{O}}).

Next, the user needs to specify probabilistic functions, namely the probabilistic outcome function Θp ((Pr(o| {mathcal{B}}))), the probabilistic Karma transition function Ωp ((Pr({k}^{t+1}| {k}^{t},{{mathcal{B}}}_{e},{o}_{e,j}))), and the probabilistic urgency transition function Ψp (Pr(ut+1∣ut, o, τ)).

Afterwards, the user needs to specify logic functions that determine payments between participants δki and/or a Karma overflow account Z that can be used for redistribution of Karma (i.e., property tax) and payments to the society (distribution of Karma): the cost function (C([{u}_{j},{o}_{j}]to {mathbb{R}})), the temporal preference function T (([{tau }_{i}]to [0;1]in {mathbb{R}})), the outcome function (({{mathcal{B}}}_{e}to {o}_{e})), the payment function (([{a}_{j},{o}_{j}]to [left{delta {k}_{i}forall iin {mathbb{N}}right},Z])), the urgency transition function ([ui, oi] → ui), the overflow distribution function ((left[left{{k}_{i}forall iin {mathbb{N}}right},Zright]to left{delta {k}_{i}forall iin {mathbb{N}}right})), and the Karma redistribution function ((left{{k}_{i}forall iin {mathbb{N}}right}to left{delta {k}_{i}forall iin {mathbb{N}}right})).

Table 4 connects the design parameters of the Karma mechanism with the modelling aspects of the software framework. Please note, the framework encodes the outcome oe,j = 0 as not receiving a resource (costs appear) and oe,j = 1 as receiving the resource (no costs appear).

Second, let us showcase the optimization process, which represents the computation of the Karma Game’s Stationary Nash Equilibrium, as described in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1

Behaviour prediction

1: Init social state

2: while not AbortionCriterion do

3: Adjust state space

4: Validate social state

5: Compute intermediate products (in this order)

6: Update social state

7: end while

Init social state

To initialize the state distribution, one needs to define an initial distribution across agent types, urgency levels and Karma balances. The distribution will determine the average Karma amount in the population, which needs to stay constant over the runtime of the algorithm. To initialize the policy, the software framework offers three possible initializations by default: “bottom”, “even” and “top” that represents initial policies in which the agents always bid 0 (bottom), always bid the maximum Karma amount (top) or an even distribution between them (even). We recommend “even” as we observed the convergence to proceed faster.

AbortionCriterion

As mentioned in the game-theoretic model, we employ an iterative approach to calculate the Stationary Nash Equilibrium. Over many iterations, the difference of the social state after and before the iteration decreases. While the algorithm will converge towards the Stationary Nash Equilibrium, at some point, when the precision of the social state is sufficient, one can abort the computation. A certain abortion criterion defines the sufficiency in this context. In our software framework, we recommend the user to have a dual abortion criterion: maximum number of iterations, and a convergence threshold for the differences of social states between iterations.

Adjust state space

While the Karma game, as defined in this work, could have an infinite state (possible Karma balances ({mathcal{K}})) and thus action space (possible actions ({mathcal{A}})), in practice it is impossible and unnecessary to calculate dp and πp for infinite spaces. In the software framework, we store dp and πp in arrays (tensors) of finite dimensions. We define initial state and action space based on the average initial Karma, and then dynamically expand the spaces when certain conditions are met, which make expansion necessary.

The initial state and action space need to be set by the user. We recommend an initial action space with a size equal to the average initial Karma, and an initial state space with a size equal to four times the average initial Karma (as within the first iterations the Karma distribution at the average initial Karma sinks and spills over to neighbouring Karma balances on the left and rights).

The action space is expanded, if the sum of the policy’s action probabilities of the boundary action (highest action in the space) across all types, urgencies and Karma balances, exceed a threshold value. The state space is expanded, if the sum of the distribution’s shares for the highest four boundary states (highest Karma balances in the space) across all types, and urgencies, exceeds a threshold value. We do so, to make sure there is always enough space for the distribution to expand. Based on our computations, we found that the distribution reacts sensitive to hitting the boundary, and that convergence decelerates significantly.

Validate social state

The numerical computations of the algorithm with decimal floating point numbers can cause rounding errors that accumulate over the iterations. Thus, it is important to regularly validate whether the social state is correct, and if not, to correct through normalization. The d[τ, u, k] is valid, if: (i) all the shares for different types, urgency levels, and Karma balances add up to 1.0, and (ii) the average Karma balance equals the average initial Karma balance:

The policy πp[τ, u, k, a] is valid, if the probabilities of all actions for a given agent type, urgency level, and Karma balance adds up to 1.0:

Compute intermediate products

The intermediate products are calculated using an evolutionary, best-response dynamic, as described in the game-theoretic formalization. Please note, the iterative calculation of V is initialized as V[τ, u, k] = 0, and aborted based on two criteria: (i) maximum number of iterations, (ii) convergence threshold.

Update social state

The update of the social state follows the elaboration in the game-theoretic formalization. The hyper parameters can be tweaked for specific optimization problems, and also changed adaptively over the iterations to accelerate convergence. Based on our experiences, we recommend the values λ = 1000, ϖ = 0.20, η = 0.50 as a good set of hyper parameters to start with.

Third, let us discuss the time-discrete simulation of Karma as a multi-agent system is outlined in Algorithm 2. The implemented simulator can be integrated seamlessly with other simulators, and offers storage and computation for all Karma related population values. At all times, the software framework records the population related information (type, urgency level, Karma balance, cumulated costs, number of encounters), and provides useful methods to retrieve information on the simulation progress.

Algorithm 2

Simulation

1: Init social state

2: While not AbortionCriterion do

3: Begin epoch

4: Execute interactions

a: Participant selection

b: Decision-making process

c: Determine outcome

d: Karma transactions (payments & overflow)

5: Close epoch

a: Urgency transition

b: Karma overflow distribution

c: Karma redistribution

6: end while

Init social state

In addition to the game parameters specified during modelling and optimization, the number of agents n, an initial state distribution d[τ, u, k], and the optimal policy πp[τ, u, k, a] need to be provided. By default, an initial state distribution will be derived from the computed Stationary Nash Equilibrium, in order to simulate a multi-agent system that already is in its steady state. However, there are options to initiate the system by equally distributing Karma units.

AbortionCriterion

The simulation happens in discrete periods of time (epoch), and can be repeated until a user-defined abortion criterion is met. Each epoch consists of three computation steps.

Begin epoch

The first step of an epoch is to record of the states before interactions.

Execute interactions