Label-free live cell recognition and tracking for biological discoveries and translational applications

Introduction

Importance and significance of label-free cell recognition and tracking

Label-free live cell microscope-based analysis refers to single timepoint or longitudinal monitoring of cell population behaviours in the absence of phototoxicity and labelling reagents, and is typically accomplished with the aid of computer vision algorithms due to the tedious nature of manual techniques. Within this context, it is imperative for biologists to have a solid understanding of computer vision algorithm principles and methodologies in order to capitalise on this approach’s potential to contribute towards basic and translational biomedical research. Such knowledge is crucial for biologists to make sound biological inferences and communicate with computer vision scientists when algorithms fall short of expectations. Likewise, it is equally vital for computer vision scientists to be intimately familiar with the objectives of biologists, so that their algorithm development efforts are specifically targeted for their end users’ needs.

To facilitate a clear and in-depth discussion, it is imperative for both algorithm developers (computer vision scientists) and end-users (biologists and biomedical researchers) to clarify the definition of ‘cell recognition’, which may be conflated with various Computer Science definitions associated with different levels of task complexity. For a given input (Fig. 1a), images may be categorised as to whether cells are present or absent, which is termed ‘classification’ (Fig. 1b), or alternatively localised via different methods (Fig. 1c–f). These latter localisation methods may involve using bounding boxes to delineate the approximate coordinates of individual cells, which is called ‘object detection and localisation’ (Fig. 1c), binary masks to distinguish background and foreground/cell regions, which is known as ‘semantic segmentation’ (Fig. 1d), individual masks to distinguish each cell, which is termed ‘instance segmentation’ (Fig. 1e), and individual masks that distinguish each cell as well as their cell type, which is delineated as ‘panoptic segmentation’ (Fig. 1f). In this review, ‘cell recognition’ is interchangeably used with ‘instance segmentation’, whereby distinct regions or masks (i.e. pixels) are allocated to each individual cell.

a A Zernike’s qualitative phase contrast microscope (ZPCM) image is used as input. b At the simplest level, the input image can be subjected to classification, which ascertains the presence or absence of cells in a given image. c At a low level of complexity, objects can be detected and localised via bounding boxes, which can also distinguish different categories such as cell types. d At a medium level of complexity, pixel-wise classification or sematic segmentation may be performed to distinguish foreground and background. e At a high level of complexity, individual objects (cells) may be distinguished via instance segmentation. f At a very high level of complexity, individual objects belonging to different categories (e.g. different cell types) may be distinguished via panoptic segmentation. Purple bounding boxes/outlines and green outlines in (c) and (f) enclose segmented cells. Black and white in (d) indicate background and foreground/cell regions, respectively. Different coloured masks indicate instance segmented cells.

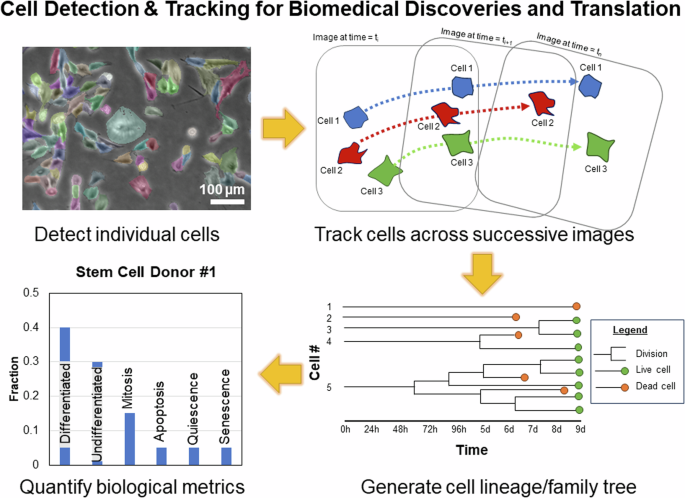

In terms of addressing the broad range of scientific questions and applications sought by biologists and biomedical researchers, label-free live cell instance segmentation and tracking is a highly versatile technique. In a typical analysis, individual cells and their resulting cell trajectories are recognised in single images and image sequences, respectively. This enables a single microscope sample to generate multiple metrics or readouts regardless of whether the sample is comprised of a single timepoint or multiple timepoints (Fig. 2). Single timepoint measurements may include various cell morphological readouts including its relative intensity, size, shape, perimeter, texture features, etc. that indicate the cell’s status such as whether the cell has undergone differentiation, mitosis, apoptosis, quiescence, senescence, etc. (Fig. 2). Multiple timepoint measurements may include not only the metrics derivable from single timepoint measurements but also additional readouts such as migration speed and genealogy/lineage information (Fig. 2). In addition, biological readouts can also be computed at the level of individual cells as well as for a given cell population. Individual biological metrics may include cell morphology, proliferation, differentiation, quiescence, migration, etc. whereas population-level metrics include cell heterogeneity, cell lineage tree, confluency, etc. (Table 1). Due to the label-free nature of these methodologies and use of transmitted white light (i.e. there is little-to-no phototoxicity and no labelling reagents to impact experimental outcomes), the readouts are representative of cells in their unperturbed or ‘natural’ state, offering valuable biological insights and potential inroads for translational applications. Hypothetically, these attributes may be useful, for example, in identifying unproductive stem cell donors for biomanufacturing (Fig. 2). In a notable example of biological discovery, Gilbert et al. performed long-term tracking of individual muscle stem cells grown in hydrogel microwells to show that substrate stiffness can affect muscle stem cell differentiation and survival1. As a demonstration of proof-of-concept for potential translational application, Ker et al. monitored time-dependent changes in myoblast confluency to demonstrate use of cell segmentation algorithms for cell biomanufacturing2. As such, label-free approaches enable researchers to attain individual or multiple snapshots of cell populations at the resolution of single cells that can discover new cellular behaviours and aid development of therapeutics for regenerative medicine.

Instance segmentation and tracking of cells across successive images enable cost-effective, real-time monitoring of cells to generate complex biological metrics to quantify cell behaviours at the level of single individual cells and whole cell populations. Different biological metrics may be used to define productive and unproductive donors to efficiently streamline a biomanufacturing process.

Given the wide breadth of basic and translational applications that may utilise label-free live cell analysis, deployment of this technology is expected to have significant impact on biomedical research productivity and translational applications. For example, there were an estimated 2,737,640 biomedical-related research articles published during 2017 to 20193 and commercial applications for label free cell analysis has a projected market size of USD 829.71 million dollars by 20284. In this regard, label-free live cell analysis can increase productivity by reducing or eliminating labour-intensive and time-consuming steps often performed in biomedical research. Notably, many regenerative medicine therapeutics involve cell-based strategies that require biomedical scientists to culture stem/progenitor cells for lengthy durations followed by labour-intensive staining to assess levels of differentiation. In work by Waisman et al., a convolutional neural network classifier was reported to detect induced pluripotent cell differentiation in unstained cells within 1 h of switching to induction media5. Also, Sasaki et al. reported that, with a LASSO regression model, cellular morphologies can be used to predict mesenchymal stem cell differentiation into multiple lineages including osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes6. Possessing such capabilities to predict cell behaviour is important, particularly in the context of expanding cells for biomanufacturing, where multi-timepoint readings such as cell confluency must be closely monitored to maintain stemness and avoid undesired cell differentiation2. In addition to predicting cell differentiation, label-free cell instance segmentation and tracking can contribute towards semi-automated, high-throughput disease diagnosis7 and drug discoveries8. Together, label-free live cell analysis can improve biomedical research productivity.

Comparison of label-free live cell imaging and sensing technologies

Label-free live cell instance segmentation and tracking can be accomplished by numerous sensing modalities including but not limited to brightfield microscopy, Zernike’s qualitative phase contrast microscopy (ZPCM), differential interference contrast (DIC)/Nomarski microscopy, electrical cell impedance sensing (ECIS), quantitative phase imaging (QPI) methods, and imaging flow cytometry. In the following section, common modalities for label-free live cell instance segmentation and tracking are briefly introduced in terms of their working principle, advantages, and disadvantages followed by an assessment on their preferential use.

Brightfield imaging is one of the simplest and cheapest forms of optical microscopy and can be found in most biological laboratories. In brief, this technique visualises a sample by passing illumination light through the sample with contrast generated due to the absorption of light by denser areas of the specimen9,10,11,12. This imaging technique is compatible with standard tissue culture vessels and its spatial and temporal resolution is dependent on both microscope objectives and camera hardware acquisition speed, respectively (Table 2)9,10,11,12. However, the semi-transparent nature of cells makes morphological details challenging to be easily visualised with high clarity (Table 2)9,10,11,12. Since brightfield microscopy is amenable to optical sectioning, there have been recent efforts to improve upon the technique by using optical sectioning to generate 3D brightfield image stacks13. Subsequently, standard digital filters can be applied to reconstruct these 3D image stack and allow for accurate visualisation of optically thin objects13.

ZPCM is a highly ubiquitous and low-cost microscope imaging modality that visualises cells with high contrast. Relative to brightfield microscopy, the fundamental basis behind this technique is the addition of a condenser annulus and phase plate that transform differences in the optical path length (after light has passed through a phase object such as a cell) into intensity changes (Table 2)9,11,12,14,15. Since optical path length differences are related to an object’s thickness and refractive index, high contrast can be generated for subcellular structures (Table 2)9,11,12,14,15. This allows for imaging of birefringent or dichroic specimens such as muscle tissue while maintaining its compatibility with standard tissue culture vessels (Table 2)9,11,12,14,15. Although ZPCM images may invariably contain artefacts such as undesired halos that obscure cellular details9,11,12,14,15, such features may be capitalised upon for cell instance segmentation16,17. Similar to brightfield microscopy, the spatial and temporal resolution of this technique is dependent on both microscope objectives and camera hardware acquisition speed, respectively, with good optical sectioning capability for relatively thin specimens (Table 2)9,11,12,14,15.

DIC/Nomarski microscopy is an optical technique that introduces contrast to specimens with a pseudo 3D effect. This microscope imaging modality is highly popular but not nearly as ubiquitous as brightfield or ZPCM due to a slightly more stringent requirement for strain-free objectives and additional costly optical elements such as Nomarski or Wollaston prisms9,12,14. The operating principle behind DIC microscopy is the use of polarised light to convert the phase delays that result after passing through a biological specimen into intensity changes for generating contrast9,12,14. Unlike typical ZPCM imaging, this contrasting effect is created locally in adjacent structures that possess different refractive indices (i.e. optical path length gradient for DIC/Nomarksi microscopy versus optical path length magnitude for ZPCM), producing the aforementioned pseudo 3D image with reduced halo artefacts9,12,14. Although these local optical path length gradients can be utilised for cell instance segmentation18, this pseudo 3D topography can often be confusing to novice microscopists. Also, this imaging technique is typically not compatible with dichroic or birefringent specimens including standard tissue culture vessels due to optical disturbances caused by differential absorption of polarised light’s ordinary and extraordinary wave components9,12,14. Similar to both brightfield and ZPCM, the spatial and temporal resolution of this technique is dependent on both microscope objectives and camera hardware acquisition speed, respectively, with an optical sectioning capability that is generally better than ZPCM for relatively thick specimens (Table 2)9,12,14.

ECIS is an alternative cell sensing approach that is less ubiquitous than the afore-mentioned microscope modalities due to its higher cost for specialised, high-end electronic hardware. ECIS measures electrical impedance distributions across cell bodies by injecting low-frequency electrical current that is suitable for sensing dynamic changes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, etc. (Table 2)19,20,21. There are no cell images or optical sectioning capability associated with this methodology and the requirement to inject low-frequency electrical current for cell sensing requires use of specialised culture vessels containing sterile and disposable electrode arrays (Table 2)19,20,21. As a result, there is poor lateral (xy) spatial resolution due to technical challenges in packing numerous electrodes together for distinguishing individual cells within confluent cultures (Table 2)19,20,21. However, ECIS has high axial (Z) spatial resolution on the order of 1 nm19 as well as high temporal resolution for monitoring time-dependent cell behavioural changes (Table 2)19,20,21. The latter is useful for measuring fast biological events as long as readings are not confounded by noise originating from fluctuations in pH or medium composition (Table 2)19,20,21.

Rather than a single technology, QPI techniques are a collection of methods that, similar to ZPCM, attain information (e.g. thickness and optical density) of objects being imaged via detection of phase shifts as light passes through them. A recent review by Nguyen et al. has comprehensively explained the principles and applications behind different QPI techniques which include interferometry-, digital holography-, wavefront sensing-, and phase retrieval algorithm-based methods and are not further elaborated upon here22. A distinct advantage of QPI methods over ZPCM is their quantitative nature, which generates high contrast reconstructed images of cells without artefacts such as halos (Table 2)22,23,24,25,26. In addition, the quantitative nature of QPI techniques can provide physical and chemical properties of cells such as the height/topography of cells27,28 or cell biomechanical attributes27,29, and the concentration of biomolecules such as haemoglobin27,30 as well as cell behaviours and dynamics such as cell growth27,31 and transmembrane water flux27,32. Such information can be useful to distinguish cell types and study cellular events vital for homoeostasis and pathogenesis27. To keep the remarks on QPI brief, readers are referred to excellent reviews by Lee et al.27, Nguyen et al.22, and Park et al.25. While the lack of imaging artefacts may facilitate higher ease of annotation for cell segmentation23, QPI methods typically require specialised, expensive and complicated setups (Table 2)26, which impede its widespread adoption. Also, although the spatial resolution is dependent on QPI methodology, the need for image reconstruction typically results in poor temporal resolution, precluding its use for studying rapid biological events (Table 2)22,23,24,25,26. Typically, QPI methods are compatible with standard tissue culture vessels and do not possess optical sectioning capabilities (Table 2)22,23,24,25,26. However, QPI variants such as gradient light interference microscopy (GLIM) possess excellent optical sectioning capabilities for thick specimens but exhibit incompatibility with standard tissue culture vessels (Table 2)22,23,24,25,26. Recent efforts have combined different techniques to overcome some of the drawbacks of QPI methods26. This includes use of an inexpensive, white light wavefront sensing that only requires minor modifications to a conventional microscope to generate QPI images26.

Imaging flow cytometry is an approach that combines the high throughput nature of traditional flow cytometry with high-speed imaging of individual cells. As an extension of conventional flow cytometry, both label-free (i.e. light scatter and image acquisition) and label-based (i.e. fluorescence staining of cells) measurements are used33,34. While data acquired using non-label-free measurements may be considered outside the scope of this review, a variation of this technique known as ghost cytometry uses can be considered label-free owing to the use of in silico labelling35,36. In brief, labelled and label-free data attained from imaging flow cytometry are used to train a machine learning-based algorithm so that it can distinguish between different cell types and cell states such as viability and differentiation35,36. After machine learning, the imaging flow cytometer can be used in label-free mode to screen and sort cells35,36. Potential applications include diagnostics such as leukaemia detection33,34,35, drug discovery approaches such as cell phenotypic screening33,34,37, and cell biomanufacturing such as enrichment of stem cell-derived progenitors33,34,38. Ghost cytometry typically requires specialised and expensive setups found in imaging flow cytometers such as multiple lasers (for labelled measurements) and detectors that can capture biological events at high speeds, which results in high cost and impedes widespread adoption (Table 2)33,34. Also, owing to the use of fluidics to measure suspension/dissociated cells, ghost cytometry has high throughput and single cell resolution but poor temporal resolution that precludes its use for tracking cells (Table 2)33,34. Since the measurement is performed on dissociated cells, compatibility with standard tissue culture vessels and optical sectioning capabilities are not applicable (Table 2)33,34.

When comparing the benefits and drawbacks for these label-free live cell imaging techniques, several key considerations emerge. These include whether a particular technique is simple, affordable, widely available, and generates high contrast information of cells to facilitate accurate cell instance segmentation. For example, while brightfield microscopy is simple, ubiquitous, and has good optical sectioning capability, the low contrast images of cells attained from this technique are a major impediment towards cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithms (Table 2). ZPCM imaging is similarly simple and ubiquitous with good optical sectioning capability for thin specimens as well as the added benefit of generating high contrast cell images despite suffering from halo artefacts (Table 2). Although other techniques such as DIC, QPI, ECIS, and ghost cytometry may be free of such halo artefacts, they typically have special requirements such as tissue culture vessels with low birefringence (i.e. DIC) or potentially expensive and cumbersome setups (i.e. ECIS, QPI, and ghost cytometry), which hinder ease of experimentation and widespread use, respectively (Table 2). Indeed, among these imaging modalities, ZPCM remains one of the most common techniques used by biologists, as indicated by the high number of search results from a simple survey of major scientific repositories for 2D microscope image datasets containing in vitro-cultured cells (Table 3). Therefore, ZPCM image data remains the most widely used for label-free imaging but at the same time, this imaging modality is greatly underutilised due to the challenges in extracting biological information.

Current challenges for label-free microscope cell instance segmentation and tracking

As a technology, label-free cell instance segmentation and tracking has broad-ranging biomedical impact and significance but must overcome several obstacles to achieve widespread usage with practical performance. Indeed, instance segmentation and tracking cells without the use of staining reagents is highly challenging, for the reasons outlined below.

First, cells are highly dynamic in nature, being able to exhibit a variety of complex irregular shapes according to cell type and culture conditions39. Also, they are able to grow in size, overlap (i.e. crawl over one another), and divide into daughter cells, which dramatically increases the complexity of cell instance segmentation and tracking tasks. In addition, modelling biologically relevant conditions often require cells to be cultured at high densities, which further exacerbates the difficulty for attaining precise instance segmentation and tracking due to substantial overlapping and clustering of cells. Furthermore, there is considerable variability in intensity and contrast for the same cell component40. For example, the boundaries of a dividing cell appear progressively brighter as it detaches from the cell culture substrate to undergo mitosis in ZPCM. Similarly, the intensity signal from the boundary of a migrating cell may be perturbed by nearby cells. This lack of constant signal and contrast intensity can result in incorrect cell boundary prediction as well as mistakenly overestimating (oversegmentation) and underestimating (undersegmentation) of true cell numbers, negatively impacting biological analyses and interpretations40. Second, gaining biological insights require sampling sufficient cell numbers for adequately powered statistical analyses41. This necessitates low magnification (e.g. 4× or 5×) cell instance segmentation and tracking, whereby each cell is only represented by several pixels. Such low information content hinders cell identification. Third, the background of images for brightfield microscopy, ZPCM, and DIC microscopy spans the typical intensity range for cells. This results in a low signal-to-noise ratio in terms of distinguishing cells from background42,43. Unlike fluorescent images where the background pixels have zero or near-zero intensity values, this makes it particularly difficult to distinguish cells from background using intensity alone. Fourth, generating manually annotated data to develop computer vision algorithms is highly tedious and time-consuming, requiring several hundreds to thousands of man-hours as estimated by prior studies41,44,45. Altogether, these reasons contribute towards the complexity of cell instance segmentation and tracking, which requires significant investment of resources to overcome. Therefore, there is no generic algorithm that can universally segment and track multiple cell types with great accuracy at the single cell-level.

In this review, we have introduced the concept of label-free cell instance segmentation and tracking (Introduction) and will subsequently describe a generalised pipeline for label-free live cell data generation for microscopy-based methods (i.e. brightfield microscopy, ZPCM, DIC microscopy, and QPI methods), cell annotation curation, computer vision-aided segmentation, computer vision metrics, and data mining (Workflows for Computer Vision-aided Cell Instance Segmentation, Tracking, and Biological Data Mining) followed by a review of different cell instance segmentation and tracking methods including image pre-processing, computer algorithm categorisation, performance metrics, basis and performance of instance segmentation and tracking algorithms, and considerations for future algorithmic development (Cell Instance Segmentation and Tracking Computer Vision Algorithms), as well as our outlook on label-free cell instance segmentation and tracking technology such as overcoming small datasets, development of novel algorithms, and emerging trends (Perspective). Although this review generalises the experimental pipeline as well as cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithms for microscope-based cell imaging modalities, several of the examples will utilise ZPCM on account of its preferential use in biological and biomedical research (Table 3). Also, ECIS is not elaborated upon further owing to its general inability for cell instance segmentation and tracking within confluent cultures, slightly lower usage relative to microscope-based methods, and different data modality (i.e. electrical signals instead of images) (Table 2). Therefore, this review aims to bridge the gap between biology and computer vision, recognising that not all biologists or biomedical researchers are familiar with computer vision concepts and not all computer vision scientists are familiar with microscope- and biology-associated concepts as well as the algorithm performance by end users.

Workflows for computer vision-aided cell instance segmentation, tracking, and biological data mining

To better apply computer vision-based cell instance segmentation and tracking, it is important to understand label-free live cell instance segmentation and tracking workflows including their associated hardware and software. Briefly, the process includes wet- and dry-lab research and can be divided into three sequential phases: data generation and cell annotation curation, computer vision-aided cell instance segmentation and tracking. Following completion of these workflows, biological data mining is subsequently performed.

Data generation and cell annotation curation

In the first phase, label-free live cell data which can be comprised of either a single image or series of consecutive images (i.e. a time-lapse sequence)41, are acquired followed by data curation to annotate cells using a combination of hardware and software.

Data generation

Numerous equipment and steps are required for acquiring label-free cell images and sequences. Generally, an inverted microscope equipped with a heated stage top incubator, humidifier, and appropriate gas cylinders and accessories for maintenance of physiological conditions, as well as on-board software for automated image acquisition are required. While such a simple setup can be homemade and customised at relatively low cost according to user requirements, commercial suppliers can provide all-in-one systems that possess additional features such as autofocus and objective heaters to prevent focus drift46, media reservoirs and tubing for automated media changes, and accessories such as optical tables to minimise vibration and ensure levelness. In any event, these systems enable rapid, automated generation of either single- or multi-timepoint microscope images for cell instance segmentation or cell tracking, respectively.

To perform data acquisition, cells are seeded at an appropriate density in tissue culture vessels, placed on the stage top incubator to maintain cell physiological state (if image acquisition occurs over a lengthy duration), and subjected to Köhler illumination for homogenous specimen lighting before a user-defined imaging schedule is executed for automated image or video collection across different culture conditions. During data acquisition, high quality data may be collected by either utilising the microscope’s autofocus feature with use of objective heaters or maintaining a fixed focus point with an adequate period of pre-heating to ensure that cells remain focused throughout the experiment. The frequency of data acquisition is dependent on the goals of a particular experiment as well as the complexity of cell instance segmentation and tracking. Typically, higher imaging rates generate more temporal and spatial information, which is expected to improve cell instance segmentation and tracking performance, but this comes at the expense of increased dataset size and data management cost. For example, Ker et al. sought to understand the effect of various growth factors on C2C12 myoblast differentiation and used a seeding density of 2 × 104 cells per 35-mm Petri dish (about 2080 cells per cm2). Due to the number of cells present over the course of the study as well as their expected migration speed, image sequences were acquired every 5 min over approximately 3.5 days, generating 49,919 images or 48 image sequences41. After acquiring the data at a suitable frequency, the image data is checked to ensure that collected image/video data are of sufficient quality (e.g. cells remained well-focused throughout the study duration), exported, and cell annotation is performed.

Cell annotation and curation

Acquired microscope images or image sequences need to be labelled or annotated prior to training cell instance segmentation and tracking models (in the case of supervised machine learning) or to generate reference cell annotations for assessing algorithmic performance. Although other computer vision studies have used the term ‘ground-truth’ interchangeably with reference cell annotations, it should be noted that human-curated cell annotations are not infallible and may contain errors. Therefore, the term ‘ground-truth’ is best reserved for scenarios where a particular annotation is known to be 100% correct. This includes cases where the cell image is relatively simple to annotate (i.e. few cells that are spaced far apart and not overlapping) or in the case of computer-generated cell images, where associated cell annotations are inherently known. As such, studies such as Maška et al.47 utilise terminologies such as ‘gold standard reference corpus’ and ‘silver standard reference corpus’. In the former, reference cell annotations reflect a majority opinion from three human experts while in the latter, the reference cell annotations are computer-generated annotations ‘averaged’ from high-performing algorithms and are informed or guided by a ‘gold standard reference corpus’47.

Typically, cells are annotated by either labelling their cell centres (known as centroids) or cell boundaries (known as masks), requiring a user either to digitally mark the centre or draw the outline of each individual cell, respectively. The latter of which, can be extremely more time-consuming than the former. This can be performed in generic computer vision annotation software such as Cell Annotation Software48 or in specialised biomedical software such as ImageJ (Manual tracking with Trackmate Plugin) (Table 4). This is a crucial step and due to the need for expert human input, can be highly tedious, labour intensive, costly, and time consuming. Indeed, Ker et al. reported that about 1.5 years was required for partial annotation of 48 image sequences after accounting for various logistics including personnel recruitment and training41.

In this regard, various data annotation strategies exist and include internal labelling, crowdsourcing, outsourcing, synthetic labelling, and automated labelling (Table 5).

Internal labelling refers to the in-house generation of annotations and has the benefit of producing high quality annotations owing to the ability to recruit or train personnel with a high level of expertise but may suffer from high cost and slow annotation41.

Conversely, crowdsourcing is a strategy that utilises recruitment of non-experts for cheap, rapid annotation generation but may suffer from inconsistency in annotation data quality49. For example, a common crowdsourcing platform, Amazon Mechanical Turk (https://www.mturk.com/), has previously been used by researchers for generating cell annotations but an additional level of curation from an expert was required to ensure an acceptable level of annotation quality50. In this regard, outsourcing the data annotation to a private company may represent a middle ground in terms of achieving adequate data annotation quality within reasonable cost and time but reports of cell annotations being outsourced remain limited51.

As alternatives, synthetic annotation and data programming can generate cell annotations using faux image data (purely synthetic or modified from real images)44,52,53,54 or automated procedures, respectively, minimising the need for human input. Despite these benefits, synthetic annotation and data programming also have their own potential drawbacks in that synthetically generated data may not represent the full range of possible cell morphologies and automated procedures may not be sufficiently versatile to correctly annotate the image data for every instance.

As a means to reduce the copious amount of cell annotation work, fluorescence stains have been utilised for generating reference cell annotations55. However, applying fluorescent molecules can induce phototoxicity56 or may perturb cell behaviour. As such, fluorescence stains must be used sparingly to maintain the physiologically relevance of the experiments.

Therefore, cell annotation is a highly tedious and labour-intensive process, which may be addressed by employing different labelling strategies, each with its own trade-offs.

Computer vision-aided cell instance segmentation and tracking

In the second phase, computer vision-based algorithms are used to perform cell instance segmentation and tracking, which requires a combination of computer hardware and software being implemented in a series of well-defined steps.

Cell instance segmentation and tracking hardware and software resources

In order to process the tremendous amount of data in a relatively short time, dedicated hardware and software systems are required. This involves identifying and recognising desired image features or patterns within the data and is highly computationally intensive primarily due to the need for pre-processing data as well as building/training computer vision models.

Typically, powerful hardware may entail a computer equipped with either graphics processing units (GPUs) or tensor processing units (TPUs), which allows for numerous parallel computations such as matrix multiplications to tuning model weights for rapid machine learning57,58. As an alternative, such resources may be available via Cloud computing, which can be purchased from commercial vendors including but not limited to Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud Platform, IBM Cloud, Microsoft Azure, etc.

To perform computer vision-aided cell instance segmentation and tracking, a variety of packaged software or custom algorithms may be used. For packaged software which includes websites, they typically feature a graphics user interface (GUI) for ease of use and owing to the generalisability as well as interoperability of various underlying cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithms (Table 6). These software programmes and websites enable biologists with little-to-no algorithmic knowledge and computer prowess to perform cell instance segmentation and tracking unhindered by any technological barriers. For custom algorithms, these are typically non-GUI software that may be implemented via frameworks such as the popular Tensorflow, PyTorch, Deeplearning4J, Apache, MXNet, etc. (Table 7). Such custom algorithms may be available on code repositories such as GitHub, which contain features such as tracking coding changes across different algorithm versions as well as integrated issue and bug tracking that facilitate code reusability and improvements. Several of these frameworks may also be implemented in a variety of data science-associated programming languages such as R, Python, MATLAB, which offers added versatility in terms of subsequent biological data mining. This is due to the large number of data science libraries available in these environments for extracting or extrapolating knowledge and insights gleaned from cell instance segmentation and tracking results.

Together, the availability of such hardware and software facilitate the cell instance segmentation and tracking process.

Cell instance segmentation and tracking procedure

Cell instance segmentation and tracking is a multi-step procedure that involves identifying and extracting relevant image features and patterns from microscope images, which includes (i) data preparation, (ii) algorithm execution, as well as (iii) performance assessment and iteration.

Data preparation

During the data preparation phase, collected, prelabelled microscope images are pre-processed, augmented, and allocated for downstream algorithm execution and performance monitoring.

Primarily, pre-processing involves applying digital alterations to images for optimal algorithm performance, which are subsequently detailed (Cell Instance Segmentation and Tracking Computer Vision Algorithms). Data augmentation is an optional step in data preparation, and involves steps that increase data size to improve algorithm or model development. In the case of machine learning-based methods, data augmentation can reduce model overfitting by increasing data size via incorporation of slight modifications to image datasets59. Such transformations may include positional augmentation (flipping, rotating, etc.), tone augmentation (adjustment of brightness, contrast, gamma, and saturation), deformation augmentation (applying elastic, free-form, or other deformations that alter the appearance of cells within the image), and other more advanced techniques (e.g. data simulated from an appropriate statistical distribution).

In addition, data are typically separated for performance evaluation. According to current practice, data may usually be pre-segregated into three batches which include a training set, a validation set, and a test set60, but variations of this method such as k-fold validation may also be employed if the sample size is considered to be small61. Typically, the training set includes the majority of the image data, and is used to train/build a model and adjust relevant parameters. The validation set provides a pseudo-independent data for semi-unbiased evaluation of the trained model, which permits further tuning of algorithm parameters and hyperparameters. As decisions on parameter and hyperparameter tuning may be made in reference to the validation dataset’s performance, this data cannot be regarded as being truly independent. As such, once a model is fully optimised, the truly independent test set is used to test the performance.

Altogether, the data preparation phase is a crucial step for optimising subsequent algorithm execution.

Algorithm execution

During algorithm execution, appropriate algorithms or models are chosen for cell instance segmentation and tracking.

The choice of the algorithm used is primarily dependent upon the scientific question(s) of interest, minimal accuracy required to attain biologically meaningful results and interpretations to answer the scientific question, and the quantity as well as quality of data collected, which can be impacted by image attributes and the difficulty level of the task. Such factors include the cell type (e.g. suspension cells which often exhibit simple round morphologies that are easy to segment versus adherent cells which may exhibit more complex and dynamic shapes), cell density (low-density cell instance segmentation and tracking is simpler than that of high-density), magnification (lower magnification is more challenging due to less pixel information per cell), image quality (optimal exposure and well-focused images make for easier cell instance segmentation and tracking versus suboptimal exposure and out-of-focused images), and imaging frequency (high frequency make for easier tracking than low frequency).

Other crucial considerations may include algorithmic training time and inference speed, and resources in terms of personnel, available hardware, and overall cost. In the case of non-machine learning-based methods, appropriate parameter values are imputed to execute the algorithm. These parameter values vary greatly according to the type of algorithm as well as biological qualities such as an intensity value for separating foreground and background (in the case of thresholding) or the expected average cell size. In the case of machine learning-based methods such as supervised learning, selected models need to be trained to segment cells or perform tracking. During training, pre-processed and prelabelled data is used as input to be processed by the learning algorithm for several epochs, which is a value defined by the user and refers to the number of times the entire training dataset is handled or ‘seen’ by the learning algorithm. By iteratively comparing the expected results for the prelabelled training data with its current performance, the machine learning algorithm builds a model that learns the data distribution in order to make accurate predictions for data which it has never previously encountered. When completed, the performance of the algorithm is next evaluated.

Performance assessment and iteration

Evaluation of cell instance segmentation and tracking results is performed by comparing the prediction of the training and validation datasets with its corresponding reference cell annotations. Where necessary, parameter or hyperparameter values may be changed to attain improved performance. However, users must carefully choose their parameter and hyperparameter values to avoid model overfitting, which may result in achieving good predictions but only for the given dataset, lowering the predictive power of the model. In the case of neural network-based deep learning, fine tuning of parameters and hyperparameters such as the number of epochs, learning rate, choice of optimisation algorithms (e.g. gradient descent), activation functions (e.g. Sigmoid, ReLU and Tanh), loss functions (e.g. mean-squared error and Hinge loss), number of hidden layers, pooling size and batch size, etc. can dramatically impact performance. This process is highly iterative and may require a fair amount of empiricism in order to achieve optimal performance. Thereafter, the algorithm or model with its optimised parameter and hyperparameter settings can be used to make prediction with the test data in order to make a final assessment of its performance on an independent dataset before proceeding to data mining.

Biological data mining

In the third phase, data mining of cell instance segmentation and tracking results is performed to extract biological meaning from the processed datasets. This requires a combination of computer hardware and software as well as user-defined metrics that answer the scientific question(s)-of-interest.

Data mining hardware and software resources

Similar to cell instance segmentation and tracking, data mining typically requires powerful computer workstations equipped with dedicated software. Typically, processing of large datasets requires computers with powerful central processing units (CPUs) and a large amount of random-access memory (RAM) as opposed to GPU-equipped workstations for executing cell instance segmentation and tracking. However, in recent years, there have also been studies exploring the use of GPU-equipped computers to perform data mining62. Various commercial and open-sourced software can then be installed on such systems to perform data mining. Commercial statistical and data mining software include SAS (SAS Institute, https://www.sas.com/en_us/home.html), SPSS (IBM, https://www.ibm.com/spss), Tableau (Tableau, https://www.tableau.com/), MATLAB (Mathworks, https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html), etc. while free and open-source data science programming languages such as Python, R, Julia, which may be used with various GUI-based integrated development environment for ease of code execution and data visualisation. While each of these software packages or data science programming languages have their own strengths and weaknesses that are beyond the scope of this review, they all serve to extract biologically meaningful interpretations from the data.

Extracting biologically meaningful interpretations

After computer vision-aided cell instance segmentation and tracking has been performed, the output is typically low-level information that must be transformed into higher level biological knowledge.

For cell instance segmentation results, individual cells within an image are typically represented as centroids or masks, with each pixel of an image associated with a unique cell identification or ID number (i.e. pixels belonging to the same cell have the same ID number). From such information, biologically relevant knowledge such as cell numbers, size, perimeter, shape, etc. can be computed from the number of unique cell IDs, cell area, total cell boundary length, aspect ratio/circularity/elongation shape, etc., respectively41.

For cell tracking results, individual cells across multiple images are associated with the same cell ID number, allowing other measurements such as cell migration (and directionality), cell cycle, lineage tree, etc. to be computed from changes in cell position across time, duration from cell birth to cell division, and mother-daughter cell relationships (due to implicit or explicit mitosis detection) as a function of time, respectively41. Also, biologists and biomedical researchers may define parameters to measure individual cell state such as quiescence (e.g. did the cell divide within a user-defined period) or population-based metrics such as growth fraction (e.g. what was the proportion of cells actively undergoing cell division within a user-defined period) as previously stated (Table 1 and Introduction). Once computed, these values may be compared within the same experimental group to answer scientific question(s) such as the level of heterogeneity within a stem cell population or compared across different experimental groups to determine the impact of a particular condition such as the effect of a drug on cellular activities.

Indeed, biological information derived from label-free cell instance segmentation and tracking results can provide powerful tools in basic studies and translational applications. In basic neuroscience studies, morphological information such as the total number of neurites and branch tips are crucial for understanding a neuron’s tree-like structure as well as how neural information is transmitted63. Such analyses can be highly sensitive, enabling closely-related cell subtypes to be distinguished on the basis of their axonal morphology63. In this context, it has been recently recognised that combinatorial use of label-free monitoring approaches with primary cells enable long-term studies of functional neurons under physiologically relevant conditions64. In drug discovery, the ability to mine image data for rapid identification of potential lead compounds is vital65. This is because drug discovery costs are at an all-time high66 with the median and mean cost of bringing a new drug to market estimated at $985.3 million and $1335.9 million, respectively67. Image-based profiling for drug discovery can aid screening of disease-associated phenotypes, understanding disease mechanisms, and predicting a drug’s activity, toxicity or mechanism of action65. For instance, non-label-free methodologies such as Cell Painting, which uses several fluorescent dyes to stain different cellular structures, can yield a variety of morphological features for profiling68. This approach has been used to identify copper-based small molecules for oesophageal cancer treatment and elucidate a mechanism of action for copper-dependent cancer cell killing69. In this context, label-free approaches could benefit the drug discovery process in the same manner with the added benefit of increased speed as well as the elimination of staining reagents and associated manpower costs, as demonstrated by Kobayashi et al. 70.

Thus, the data mining algorithms employed are dependent upon the biological or biomedical question(s)-of-interest and have many potential applications in both basic science and translational medicine.

Summary of workflows for computer vision-aided cell instance segmentation, tracking, and biological data mining

In summary, generating cell instance segmentation and tracking data involves three distinct phases – (i) data generation and cell annotation curation and (ii) computer vision-aided cell instance segmentation and tracking, which is subsequently followed by (iii) biological data mining. Each of these phases require distinct hardware and software. For example, the first phase requires microscopes equipped with time-lapse hardware that maintain physiological conditions and utilise software-driven schedules to automate image acquisition as well as cell annotation software while the latter two phases primarily require powerful workstations to perform image processing and data mining. Also, various strategies, considerations, and procedures exist for annotating cells, choosing the algorithm(s) for cell instance segmentation and tracking, and methods of extracting biologically meaningful interpretations from the data.

Cell instance segmentation and tracking computer vision algorithms

Numerous approaches for cell instance segmentation and tracking have been developed. In this section, image pre-processing steps vital to algorithm performance are first outlined, followed by discussion of how cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithms are categorised, how algorithmic performance is measured, the basis for various cell instance segmentation and tracking approaches and their associated performance, as well as vital considerations for future algorithmic development and performance.

Image pre-processing

As previously mentioned, prior to application of cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithms, images may first undergo pre-processing to ensure optimal performance. These may range from simple methods such as altering image brightness71,72 to complex image reconstruction steps that remove image artefacts such as halo and shade-off16,73.

For simple methods, typical pre-processing methods include illumination correction (e.g. background subtraction, intensity normalisation, etc.) to eliminate background noise and increase signal-to-noise ratio, cropping to remove redundant background, rescaling image size to reduce computational burden, improving image quality via image alterations (e.g. inverting images, applying contrast enhancement, applying median, Gaussian, Poisson, mixed Poisson-Gaussian filter, and Kuwahara filters, erosion or dilation morphological operations, etc.). Such procedures can be performed in GUI-based software packages or via programming languages such as R and Python.

For complex methods, image reconstruction may involve modelling the process of microscope image formation, which can generate a linear imaging model that restores an artefact-free ZPCM image with cells represented as bright (positive-value) pixels on a uniformly black (zero-value) background16,73. The restored image corresponds directly to the specimen’s optical path length and cells can be subsequently segmented using simple methodologies such as thresholding with high accuracies16,73.

Overall, pre-processing alters images to achieve improved algorithmic utilisation and performance, and is an important step prior to execution of cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithms.

Categorisation of computer vision algorithms

In reviewing cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithms, it is vital to employ a categorisation scheme that is easy for end users unacquainted with algorithm development to understand.

It is worth noting that various original research or reviews may employ different schema to categorise algorithms. For example, Ulman et al. 44. chose to group cell instance segmentation algorithms according to three interrelated criteria: (i) the guiding principle on which cells are segmented, (ii) the image features associated with this segmentation principle, and (iii) the computational steps used to segment the said associated image features whereas Niketia et al. 74 used four categories according to common methodological approaches: (i) classical/traditional approaches based on mathematical morphology, (ii) cluster-based segmentation, (iii) probabilistic-based models, and (iv) learning-based models. Similarly, Ulman et al. 44 chose to group cell tracking algorithms according to the following schema: (i) contour evolution-based methods and (ii) tracking by detection whereas Emami et al. 75 grouped algorithms accordingly to three distinctive methodological approach: (i) tracking by detection, (ii) tracking by model evaluation, and (iii) tracking by filtering. It should be acknowledged that there is no strict dichotomy that may prove all-encompassing and definitive since these algorithms are highly varied in their approaches, constantly evolving, and may employ a combination of existing procedures that makes organising them into well-defined categories with little-to-no overlap challenging.

In considering the need for a simplistic dichotomy based on both technical approach and common usage, this review uses the concept of how image features or representations are extracted as the discriminating factor. Briefly, image features are pieces of information that are utilised in a particular computer vision task. For example, edges are image features where there are sharp discontinuities such as changes in brightness or colour. These edges can represent the boundaries of cells and thus provide useful information to aid individual cell segmentation. Therefore, image features are key determinants of algorithmic performance and they can be extracted or engineered via expert domain knowledge, as is the case for a majority of traditional/classical computer vision algorithms, or learned in the absence of explicit feature engineering via input of labelled data into artificial neural network/deep learning computer vision algorithms. Notably, deep learning algorithms have seen a dramatic rise in usage and popularity in recent years, in part owing to increased hardware capabilities, open-sourced software libraries that enable rapid graphics processor unit (GPU)-based training, and development of novel and high performing model architectures.

Thus, this review will categorise cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithms according to this dichotomy of traditional/classical computer vision algorithms and deep learning.

How is cell instance segmentation and tracking evaluated: an overview of performance metrics

While the prospect of label-free cell analysis offers biologists and biomedical researchers an exciting tool for answering their scientific questions, it is equally important for them to be familiar with the performance metrics associated with cell instance segmentation and tracking so that they understand the underlying quality and precision of their data. These include computer vision, biological, and other performance metrics which summarise the precision by which algorithms can segment cells (i.e. within a single image/time frame) or track them across multiple images (i.e. over time).

Computer vision metrics

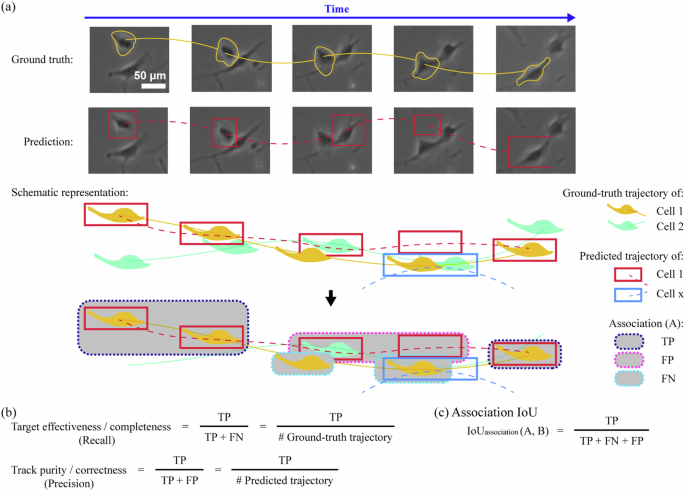

To assess the performance of such algorithms, various types of computer vision-based cell instance segmentation and tracking metrics are employed (Figs. 3–5). A majority of these metrics compute values on a scale from 0 to 1, representing 0% to 100% performance. For segmentation tasks, a common type of metrics used is associated with a mathematical contingency table called confusion matrix76. Briefly, constructing a confusion matrix involves recruiting a domain expert to inspect an input image (Fig. 3a) and produce reference cell annotations/labels (Fig. 3b). This is followed by the generation of cell predictions by computer vision algorithms (Fig. 3c) and their subsequent assignment into four different categories which include false negatives (FNs), false positives (FPs), true positives (TPs) and true negatives (TNs) (Fig. 3d). The latter assignment depends on user-specified criteria such as intersection over union (IoU) thresholds (α), which delineate how closely the predictions must concur with expert-generated reference cell annotations before being accepted as TPs (Figs. 3d and 4a). Upon such assignment, additional metrics can be computed including precision (Fig. 4b), recall (Fig. 4b), false positive rate (Fig. 4b), precision-recall (PR) curve (Fig. 4c), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (Fig. 4d), Dice coefficient score/F1-score (Fig. 4e), Jaccard index/IoU/detection accuracy (Fig. 4f), and average precision (AP) as well as mean average precision (mAP) (Fig. 4c, g)76,77. Alternatively, metrics such as SEG and DET scores have been developed for the Cell Tracking Challenge benchmark44,47,78. The SEG score measures the average overlap between a reference cell annotation and predicted segmentation masks whereas the DET score is similar to a weighted version of the F1-score (which favours recall over precision) and is defined as a normalised acyclic oriented graph matching measure44,47,78. Besides confusion matrix-related metrics, there are also distance-based metrics, such as Hausdorff distance79, that may also be used but are less popular. Briefly, Hausdorff distance refers to the maximum distance for two (matched) point pairs of segmentations (i.e. between reference annotation and prediction) and has the benefit of being less sensitive than Dice coefficient score and Jaccard index to small changes in the segmentation mask boundaries79. A comprehensive review on the various types of detection and segmentation metrics is beyond the scope of this article and may be found in an excellent review from Maier-Hein et al. 76. For tracking tasks, similar evaluation metrics based on the confusion matrix are used (Fig. 5). In a particular image sequence (Fig. 5a), these metrics include target effectiveness/completeness, track purity, and association IoU, which are the cell tracking counterparts for recall, precision, and IoU metrics, respectively (Fig. 5b). Other studies may employ metrics such as multiple object tracking precision (MOTP) and multiple object tracking accuracy (MOTA)80. MOTP assesses the total error in predicted positions for matched object-hypothesis pairs over all frames, averaged by the total number of matches recognised and is similar to the Jaccard index/IoU/detection accuracy used in segmentation tasks while MOTA assesses object tracking errors such as missed events, mismatch events, and false positive events80. In addition, the Cell Tracking Challenge benchmark44,47,78 has developed an alternative tracking metric known as TRA, which is a normalised weighted distance between the a reference cell annotation with the predicted cell trajectories, weighted by the effort required to perform manual curation. Thus, various computer vision metrics such as those associated with confusion matrices can be used to assess cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithm performance.

a A ZPCM image is acquired for cell annotation. b Expert-generated reference cell annotations (light blue) are used to assess cell instance segmentation performance. c A computer vision-based algorithm or model performs cell instance segmentation inference/prediction (purple). d Assignment of the false negative (FN) in light blue, false positive (FP) in purple, true positive (TP) in dark blue, and true negative (TN) in grey.

a Schematic example of cell instance segmentation and how IoU is computed in relation to a user-defined threshold (α) for comparing the overlap between a reference cell annotation and a predicted cell. b Fundamental metrics for cell detection and segmentation include but are not limited to recall/true positive rate, precision and false positive rate. c Additional cell detection and segmentation metrics include the precision-recall curve, (d) receiver operating characteristic curve, (e) F1-score/dice coefficient score, (f) Intersection over union (IoU)/Jaccard index/detection accuracy. g Such methods can be used to compute average precision, which refers to the area under the precision-recall curve across a range of confidence threshold values and mean average precision, which refers to the mean of the average precision across multiple classes (i.e. cell types). Abbreviations: FN false negative, FP false positive, TP true positive, TN true negative, PR precision-recall, ROC receiver operating characteristic, IoU intersection over Union, and mAP mean average precision.

a Schematic representation of cell tracking for ground truth and prediction. b Computational metrics for cell tracking include but are not limited to target effectiveness/completeness, track purity/correctness, and association IoU. Abbreviation: IoU intersection over union.

Biological metrics

As an alternative means of assessing the performance of such algorithms, various types of biology-associated cell instance segmentation and tracking metrics are employed. For segmentation tasks, common metrics used include whether the number of cells76, cell size76, and cell centroids41,81 have been correctly predicted. Such metrics can be directly associated with biologically relevant interpretations. For example, accurate quantification of cell counts, sizes, and centroids as a function of time are informative of cell proliferation, growth, and migration, respectively. For tracking tasks, common metrics used include complete tracks, track fractions, branching correctness, and cell cycle accuracy44,47,80. Similar to frequently used computer vision-based metrics, these tracking assessment range in values from 0 to 1, representing 0 to 100% performance. Complete tracks compute the fraction of reference annotation cell tracks that can be reconstructed in its entirety and is informative where biological questions pertaining to cell lineage is vital44,47,80. Track fraction averages the proportion of correctly predicted cell trajectories with respect to the reference annotation and is useful in cell migration analysis44,47,80. Branching correctness and cell cycle accuracy measure the accuracy of mitosis detection and cell cycle length, respectively, which are indicators of population growth44,47,80. Thus, various performance metrics associated with frequently sought after biological readings can be used to assess cell instance segmentation and tracking algorithm performance.

Other metrics

In addition to computer vision-based and biological metrics, it is also worth considering usability-driven and carbon footprint-oriented measures. Usability-driven measures are largely concerned with ease-of-deployment (i.e. how rapidly and easy to generate cell instance segmentation and tracking results), including the time to train/execute an algorithm, algorithm complexity in terms of number of tuneable parameters, and generalisability in terms of performance on a similar dataset with the provided parameter settings44,47. For the former two usability measures, a faster time and smaller number of tunable parameters are indicators of high usability. For the latter, Ulman et al. computes generalisability as the average of SEG and TRA scores obtained on a similar set of image sequence(s) with assessment values ranging from 0 to 1, representing 0 to 100% generalisability in technical performance44,47. Carbon footprint-oriented measures seek to track energy consumption in the course of developing machine learning models for reducing the environmental impact of such work82,83. Typically, energy consumption in terms of kWh for different approaches are reported. Such analyses can be monitored using tools such as CarbonTracker82 to determine total energy consumption while other tools may breakdown analyses in terms of energy usage by various computer components such as the CPU, GPU, and memory83. Altogether, usability-driven and carbon footprint-oriented measures are gaining recognition as alternate means of assessing cell instance segmentation and tracking performance.

Cell instance segmentation algorithms

As a comprehensive review of all forms of computer vision segmentation algorithms is beyond the scope of this review, emphasis has been made to explain the inner workings of widely used cell instance segmentation algorithms with the end user (biologist) in mind. This information is presented according to a simple schema that includes traditional/classic non-neural network-based and contemporary neural network-based cell instance segmentation. Readers should note that while various cell instance segmentation metrics associated with different approaches are reported, such performance is highly dependent on individual dataset characteristics and complexity. Therefore, the algorithm performance summarised here may not be generalisable across different datasets and should only be used as a reference.

Traditional/classic non-neural network-based cell instance segmentation algorithms

Numerous traditional/classical cell instance segmentation algorithms have been developed, each with their own strengths and limitations. Traditional/classical algorithms include but are not limited to thresholding, kernel-based techniques, distance transform, watershed, clustering-based approaches, active contour methods, energy minimisation methods, random forest, and support vector machines.

Thresholding

Thresholding involves selecting an optimal value for an image feature such as brightness (i.e. pixel value) and discarding values below this threshold. Typically, cells in ZPCM images have bright halos surrounding them and thresholding may be useful in distinguishing their boundaries. As one of the earliest image segmentation methods, thresholding is rapid to perform but may suffer from problems that it is not generalisable to datasets that are highly variable in nature84,85,86. Numerous variations on this method exist and may include: local thresholding where subsets of an image are subjected to thresholding based on local image characteristics84,85, Multi-Otsu thresholding where the histogram of an image’s pixel values is examined and thresholds are automatically computed based on a defined number of categories input by the user86, etc. Typically, thresholding may be applied onto less challenging images that have undergone pre-processing. For example, Yin et al. built a mathematical model to approximate the process of ZPCM image formation, which generates restored images of bright cells on a uniformly black background16,73. These restored images are highly amenable to thresholding and outperformed other computer vision algorithms to attain accuracies of 97.1–90.7% in two separate image sequences16,73. As such, thresholding is a simple and rapid algorithm that can achieve good cell instance segmentation performance on pre-processed images.

Kernel-based techniques

Kernel-based techniques involve applying a matrix or array of numbers called a kernel across an image via a mathematical procedure known as convolution. Briefly, convolution involves the sequential or stepwise sliding of a kernel across the (image) data. During this process, an algebraic operation called the dot product is computed by multiplying each point in the kernel by each corresponding point in the data followed by the summation of these multiplications. This net result of convolution is a filtered image in which a variety of desired effects such as a sharper image, image with fewer noise, etc. is produced.

Within the context of segmentation, convolution results in pattern matching whereby desired image features are extracted and shown as bright pixels against a dark background84,85. Such filtering may be useful to distinguish cell boundaries via edge detection while shape recognition may be useful in segmenting cells that exhibit a regular shape (e.g. nonadherent cells typically have round morphology). Similar to thresholding, kernel-based image processing is rapid to perform but may suffer from problems in that it is not generalisable to datasets that are highly variable in nature84,85. Typically, the Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) or ‘sombrero hat’ kernel is employed owing to its ability to segment binary large objects (blobs; bright regions against a dark background or vice versa)39 but other kernels useful in detecting edges (e.g. Canny, Sobel, etc.) or simple shapes such as rings87 may also be used. For adherent cells, their highly variable shape typically contributes towards poor cell instance segmentation performance. Indeed, several variations of cell instance segmentation employing LoG kernels on unreconstructed ZPCM images achieved Dice coefficient ranging from 43% to 52% only39. For nonadherent cells, they typically appear as round objects surrounded by bright halos. Based on these image features, Eom et al. designed a bank of ring filters that achieved 96.5% precision and 94.4% recall on unreconstructed ZPCM images, which outperformed Hough transform—and correlation-based methods.

Thus, kernel-based techniques are simple and rapid algorithms that can achieve good cell instance segmentation performance for non-adherent cells that exhibit regular shapes.

Distance transform

Distance transform is based on the principle that the centre for objects-of-interests i.e. cell centroids are farthest away from the background. This involves devising mathematical criteria for computing the distance of all background pixels to the nearest object pixel or vice versa88. For instance, consider the simplest scenario of a binary image where cell regions are given a pixel value of 0 and the background has a pixel value of 1. By computing the Euclidean distance for all pixels in an image with their nearest nonzero pixel, local maxima or peaks will be generated that can be used to separate cells whose boundaries overlap88. Similar to thresholding and kernel-based approaches, distance transform is rapid to perform (on binary images) but disadvantages include the requirement for some form of foreground and background segmentation to be performed beforehand as well as its susceptibility for generating numerous false positives39,88. Numerous variations to address these flaws exist and Dice coefficients ranging from 49% to 80% have been reported on unreconstructed ZPCM images39. A notable variation of distance transform is grey-weighted distance transform, which uses cell shape and intensity information to segment neighbouring or clustered cells with an accuracy rate, positive predictive value, and recall of 97.16%, 98.82% and 98.64%, respectively89. As such, distance transform is a useful algorithm that can achieve good cell instance segmentation performance when used in combination with other methods.

Watershed

The watershed algorithm is a region-based method of segmentation that involves using the image brightness or intensity to create a topographical relief map (bright pixels = high regions whereas dark pixels = low regions) that is subsequently filled or flooded to create distinct regions representing individual objects. The term ‘watershed’ is derived from Geology and refers to the divide which separates adjacent basins, which within this context would typically represent the boundaries of cells. The watershed algorithm is robust and can be applied across different imaging modalities such as ZPCM and fluorescence microscope images but it is prone to oversegmentation (generating too many segments)39,84,85. As a result, variations such as marker-based watershed have been developed to minimise this issue. In Vicar et al., marker-controlled watershed as a standalone algorithm achieved a Dice coefficient of 41% on unreconstructed ZPCM images, which can be improved to 52% when used in combination with thresholding and distance transform39. Thus, watershed achieves reasonable cell instance segmentation performance when used in combination with other methods.

Clustering-based approaches

Clustering algorithms operate on the principle that regions of an image with similar image features belong to the same object. Such image features may include brightness, texture, colour, etc., and numerous variations such as k-means clustering and mean-shift exist84,85. k-means clustering is a popular choice for segmentation due to its simplicity and operates by first randomly dividing an image into k number of clusters and assigning individual datapoints (feature points) to the nearest mean84,85. Upon completing this assignment, the mean for each cluster is recomputed and feature points are reassigned84,85. This latter process repeats until the means no longer move, indicating convergence upon a solution84,85. However, drawbacks of k-means clustering include requiring the number of clusters to be specified and sensitivity to initialisation conditions84,85. Such drawbacks can be addressed by using the mean-shift algorithm, which automatically identifies the number of clusters within the data for simultaneous cell instance segmentation and tracking but clever strategies to overcome the model’s slow inference speed must be devised90. Owing to the complexities of cell instance segmentation, K-means clustering is typically used in combination with other methods rather than as a standalone approach91. Such attempts have achieved F1 scores ranging from 90.92% to 96.59% for three different cell types in unreconstructed ZPCM images91. As such, clustering algorithms can partition image features to achieve good cell instance segmentation performance when used in combination with other methods.

Active contour methods

The goal of active contour methods is to segment the boundaries of objects. The algorithm operates by using an enclosed curve as an initial boundary, which then iteratively shrinks or expands according to local differences present in an image84,85. Two major variations of active contours are the ‘snakes’ and ‘level set’ implementations, which utilise different mathematical approaches to govern the shrinking or expanding movement of the contour84,85. Since cells have enclosed boundaries, this algorithm is highly suited for their segmentation. The advantage of this method is the generation of sub-regions with continuous boundaries in contrast to kernel-based edge detection methods which may produce discontinuous or interrupted boundaries84,85. However, ideal parameters must be identified to ensure accurate performance as it has been noted that the contours tended to shrink too much when used to segment cells39. When used to perform semantic cell segmentation, various implementations of level-sets attained Dice coefficients ranging from 64% to 77% on unreconstructed ZPCM images39. Thus, active contour methods can achieve good semantic cell segmentation performance.

Energy minimisation methods

Energy minimisation methods formulate images in terms of an energy function and implement an algorithm that minimises this energy, resulting in the efficient partitioning or segmentation of an image. Numerous variations of energy minimisation methods exist with graph-based segmentation or ‘graph cuts’ being widely used84,85,92.

Specifically, images may first be formulated as graphs by substituting a vertex for each pixel, connecting an edge between each pair of pixels, and assigning a weight for each edge based on the affinity or similarity between two vertices84,85. Image segmentation occurs by implementing as minimal number of cuts within the graph as possible such that each partitioned subgraph only contains vertices that have high affinity for each other84,85. This typically results in good performance when performing binary cell (foreground) and background segmentation but segmentation with multiple (more than 2) labels may prove problematic. Also, by implementing a minimal number of ‘graph cuts’, the algorithm may not work well for segmenting thin structures involved in cytoplasmic processes84,85. Indeed, implementation of ‘graph cut’ algorithms is typically reserved for semantic segmentation, achieving a Dice coefficient of 40–86% on unreconstructed ZPCM images. However, Bensch et al. utilised a min-cut approach to generate cell instance segmentation masks. This method leveraged on the principle that a cell’s true boundaries in positive ZPCM consistently manifests as a transition from dark to bright in an outward direction92. With this approach, an average segmentation score of 81.05% was achieved on two ZPCM image sequences92.

As such, energy minimisation techniques such as ‘graph cut’ are typically employed for semantic segmentation but can also achieve good cell instance segmentation performance.

Random forest

The random forest algorithm is a supervised (learning) classifier that is comprised of a collection of decision trees, operating on the tenet that the collective decision of a diverse group of independent trees is superior to the opinion of a single tree. Implementation of a random forest requires providing labelled data on relevant image features, which are used to build a random collection of decision trees84,85. This requirement to provide relevant image features is termed feature engineering and is crucial to performance. Poorly engineered features may not contribute towards increased performance and may instead decrease performance84,85. When constructed, each individual decision tree can produce a prediction (the equivalent of a vote) with respect to the classification task and the majority vote determines the final collective classification outcome84,85. This classification task can be a simple binary decision such as determining whether an image pixel is foreground (cell) or background (non-cell) to slightly more complex non-binary classifications such as whether pixels belong to a cell, mitotic cell, halo, or background noise84,85,91. Following this, the prediction may be further processed in combination with clustering and other classification algorithms to achieve versatile segmentation (87.66–95.98% precision and 94.43–97.20% recall) of mouse NIH3T3 fibroblasts and human U2OS bone epithelial cells in unreconstructed ZPCM images91. Thus, random forest algorithms can achieve good performance when used in combination with other methods.

Support vector machines (SVMs)