Landscape of small nucleic acid therapeutics: moving from the bench to the clinic as next-generation medicines

Introduction

Gene therapies were initially used to treat diseases during the 1960s and early 1970s, and major biological and technological breakthroughs led to the development of several safe and effective platforms.1 Nucleic acid therapeutics use engineered sequences of nucleotides to selectively modulate gene expression.2 The most prominent nucleic acid drugs are those based on antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), aptamers, short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), which enhance the effects and delivery of drug materials, revolutionize precision medicine and increase the efficacy of existing pharmaceuticals.3,4 Oligonucleotides can be designed to target specific mRNAs and are capable of treating or managing a broad spectrum of diseases.5 The mechanism of action of these drugs differs from that of traditional drugs, which in some cases helps to prevent drug resistance, especially in cancer treatment. The efficacy of these drugs can be precisely controlled by altering their sequences, structures, or chemical modifications, and their flexibility allows the medication to be tailored according to the specific needs of the disease. In recent years, researchers have developed various delivery platforms to improve the stability and bioavailability of oligonucleotide drugs, thereby enhancing their therapeutic effects.6 Currently approved nucleic acid therapeutics and drugs assessed in clinical trials are valuable for patients who previously had limited treatment options (Fig. 1).

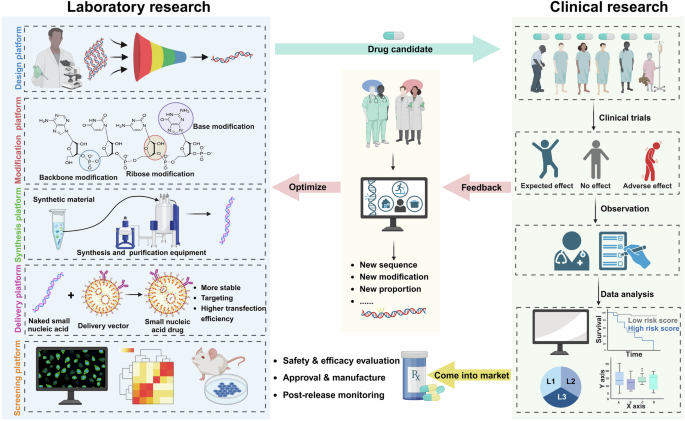

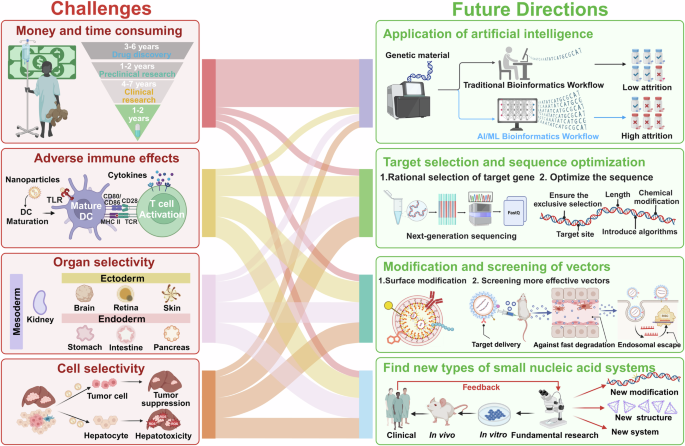

Translating small nucleic acid-based pharmacotherapy from bench to clinic and back. The development of small nucleic acid drugs begins with the design of potential nucleic acid sequences tailored to target specific diseases. Researchers then screen these sequences to identify the most effective candidates. Once optimal sequences are identified, they undergo chemical modifications to increase their stability and reduce their toxicity. These modifications optimize the drug’s pharmacokinetic properties, increasing the viability of the drug for therapeutic use. The modified small nucleic acid sequences are then encapsulated in delivery vectors. This step is crucial, as it further increases the drug’s stability in vivo and ensures that it reaches the specific target organ effectively. Extensive in vitro and in vivo evaluations have been conducted to assess the efficacy, safety, and pharmacodynamics of the drug. These evaluations help refine drug candidates before they proceed to clinical trials. Promising drug candidates then enter clinical trials, where many patients are recruited. Medical staff meticulously recorded the responses of different subjects to the candidate drugs, noting any therapeutic effects or adverse reactions. The clinical data obtained are analyzed by researchers, often with the assistance of artificial intelligence, to obtain deeper insights into the drug’s performance. This analysis helps researchers understand the drug’s efficacy, safety profile, and potential areas for improvement. The interpreted data are fed back to the laboratory for further optimization of the drug. Researchers may tweak the chemical structure, modify the delivery vector, or make other adjustments to enhance the drug’s performance. This iterative process continues, ensuring that each cycle brings the drug closer to its optimal form. This cycle of design, testing, feedback, and optimization is repeated until the drug meets the desired standards of efficacy and safety, ultimately leading to its approval and use in clinical settings

ASO technology, which originated from a 1978 study, uses synthetic strands of 15 or 20 nucleotides to complement a short RNA sequence of the Rous sarcoma virus directly.7 Based on Watson–Crick base pairing, the concept of treating a target RNA as a receptor for an ASO was proposed. Following this important finding, commercial companies focused on developing antisense therapeutics in the late 1980s to work against ‘undruggable’ receptors. High-throughput screening systems were established to identify optimal RNA binding sites for ASOs, leading to advances in ASO design. Currently, ASO drugs have been designed using this strategy, and further chemically modified ASOs have been used to enhance their pharmacological properties and passive tissue-targeting abilities.8 Additionally, RNA interference (RNAi) was first described in 1998 as a process of sequence-specific gene silencing initiated by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), sparking great interest from drug developers for its potential to suppress the expression of specific genes.9,10,11 In 2001, Elbashir et al. were the first to use siRNAs to silence the expression of different genes in mammalian cell lines. These researchers generated siRNAs against sea pansy (Renilla reniformis, RL) luciferase and siRNAs against two sequence variants of firefly (Photinus pyralis, GL2 and GL3) luciferase.12 The first proof-of-principle experiment in which siRNAs could be utilized for the treatment of a disease in an in vivo model was performed in 2003. Research has shown that an intravenous injection of a Fas siRNA specifically reduces Fas mRNA levels and protects mice from fulminant hepatitis.13 The Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology was awarded to Andrew Fire and Craig Mello in 2006 for their discovery of RNA interference (RNAi). Since then, the development of delivery systems has broadened the potential applications of RNAi, particularly in rare diseases and cancers. The first human trial started in 2008, and the data were published in 2011. A phase 1 study (NCT00689065) was designed for the systemic administration of an siRNA to patients with solid tumors via a targeted nanoparticle delivery system, and the results revealed specific gene inhibition.14 However, drug developers have struggled to place siRNA therapies on the market quickly for clinical use, and the first globally approved siRNA drug for marketing was the therapeutic patisiran (ONPATTRO™), which is used for the treatment of hereditary transthyretin (hATTR)-mediated amyloidosis.15 Since then, interest in siRNA therapies has increased, even surpassing interest in ASO therapies.

Compared with traditional small-molecule and protein drugs, nucleic acid drugs have unique advantages. Fundamentally, the main targets of traditional small-molecule drugs and antibody drugs are proteins, but only 1.5% of the human genome can encode proteins, 80% of which are undruggable targets for traditional drugs. Unlike traditional drugs, nucleic acid drugs regulate target expression by binding to related nucleic acids, which means that nucleic acid drugs are theoretically applicable to any therapeutic target. Furthermore, designing a nucleic acid drug that binds to the target gene is relatively easy once the base sequence of the target gene is known. Finally, because of the simple nucleotide synthesis process and low cost, the research and development of nucleic acid drugs are quite accessible.

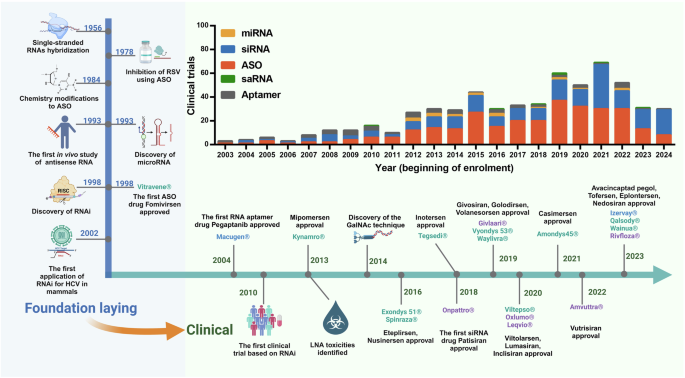

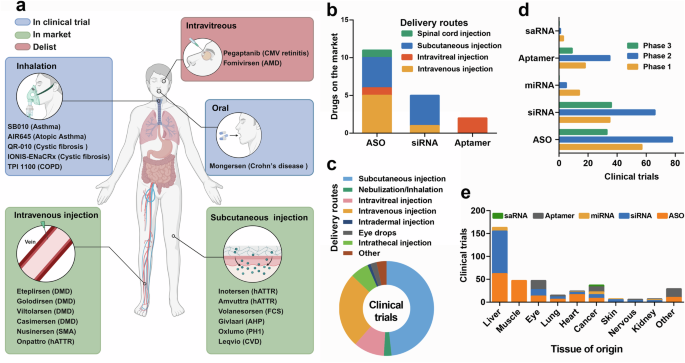

In recent years, small nucleic acid-based therapeutic modalities have expanded the platforms available for clinical oligonucleotide drug development. ASO drugs were first used on the market to control the expression of target genes. Chemical modification of ASOs is necessary for their stability and efficacy; however, the phosphorothioate or polyethylene glycol linkage in the backbone of ASOs can increase their binding affinity to unintended proteins, which is associated with toxicity. siRNA drugs with less modified linkages in the backbones can be developed as alternatives to ASO drugs. The first siRNA drug, patisiran, was approved by the FDA in 2018, and the second siRNA drug, givosiran, was approved in 2019.15,16 siRNA drugs have entered a rapid stage of development. After 20 years of research, the commercial potential and clinical value of small nucleic acid drugs have been proven (Fig. 2). In this review, we bridge the gap between laboratory research and the clinical implementation of small nucleic acid therapies, emphasizing how these technologies have evolved and are now poised for practical therapeutic use. Moreover, we focus on summarizing the latest advancements in drug delivery systems, particularly in the areas of nucleic acid chemical modification and nanoparticle carrier systems, highlighting how these improvements increase delivery efficiency. We also seek to identify the challenges and future directions in the field, discussing how these advancements could revolutionize the treatment of previously untreatable conditions.

Timeline of milestones from the discovery of small nucleic acid drugs to their clinical use. The development of nucleic acid therapeutics has been marked by considerable technological advances, pivotal drug approvals, and notable setbacks. A timeline highlighting crucial breakthroughs depicts the evolution from foundational research to clinical application. As the performance of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) has improved, the scope of therapeutic opportunities has broadened, now encompassing both rare and common diseases and virtually any delivery route. The bar graph illustrates the number of clinical trials for small activating RNAs (saRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) over the years. Each bar represents the beginning of enrollment recorded in the ClinicalTrials.gov database, providing a clear picture of the growing momentum in nucleic acid therapeutic research (up to the middle of 2024). RSV respiratory syncytial virus, RNA RNA interference, HCV hepatitis C virus, LNA locked nucleic acid, GalNAc N-acetylgalactosamine

Therapeutically relevant nucleic acids

Classification of therapeutically relevant nucleic acids

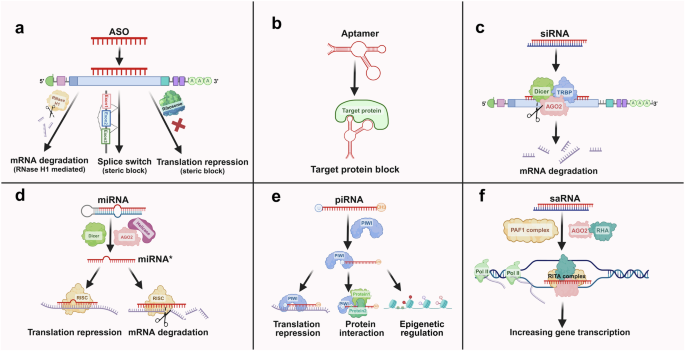

According to their molecular mechanisms, therapeutically relevant nucleic acids can be roughly categorized into eight categories: aptamer, siRNA, miRNA, ASO, small activating RNA (saRNA), PIWI-interacting RNA (piRNA), messenger RNA (mRNA) and plasmid DNA (pDNA). In this review, we focus on small nucleic acid therapeutics, in which mRNA and pDNA are not included (Fig. 3).

The functional mechanisms of four small nucleic acids. a ASOs: ASOs are short synthetic nucleic acid sequences that bind to complementary mRNA molecules. This binding can block the translation process or promote the degradation of the mRNA, thereby reducing the expression of the targeted protein. b Aptamers: Aptamers are short, single-stranded nucleic acids that bind specific targets with high affinity and specificity. They function by folding into unique three-dimensional structures, allowing them to interact with proteins, small molecules, or cells effectively. c siRNAs: siRNAs are double-stranded RNA molecules that guide the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to complementary mRNA targets. This interaction leads to the cleavage and degradation of mRNAs, resulting in the silencing of specific genes. d miRNAs: miRNAs are endogenous, single-stranded RNA molecules that regulate gene expression posttranscriptionally. They bind to complementary sequences in the 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs, typically causing translational repression or mRNA degradation, thus modulating the expression of multiple genes. e PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are small, single-stranded RNA molecules, approximately 24–30 nucleotides long. They interact with PIWI proteins to regulate gene expression, silence transposable elements, and maintain genome stability in germline cells. f saRNAs: saRNAs are synthetic short RNA molecules designed to upregulate gene expression. They bind to specific promoter regions of target genes, recruiting transcriptional activators or altering the chromatin structure to increase transcriptional activity, thereby increasing the production of specific proteins

ASOs

ASOs are short synthetic single-stranded oligonucleotides of 18–30 nucleotides in length and regulate gene expression by blocking the function of RNAs. Two major mechanisms for ASOs to exert their functions have been identified: RNase H1-dependent cleavage and steric hindrance.17 In the RNase H1-dependent mechanism, the ASO always contains a central contiguous sequence of 8–10 deoxynucleotides sandwiched between two RNA flanking regions, termed the ‘gapmer’ pattern.6,18 After binding, RNase H1 cleaves the target RNA strand, including the mRNA and pre-mRNA strands, approximately 7–10 nucleotides from the 5′-end of the duplex region since RNase H1 is robustly active in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm.19,20 In the RNase H1-independent mechanism, ASOs bind to target RNAs with high affinity, causing steric hindrance to alter gene expression by masking specific sequences rather than cleaving RNA.5 After the ASO binds to the initiation codon of an mRNA, steric interference prevents ribosome binding, thus inhibiting mRNA translation. Additionally, ASOs are also used to increase target gene expression.21 When multiple open reading frames (ORFs) exist in an mRNA, binding of the ASO to the initiation codon of the upstream ORF can alleviate translation inhibition of the main ORF, thereby activating the expression of the target protein, which is typically suppressed by the ORF.22 Moreover, ASOs can activate gene expression by masking premature termination codons or the exon junction complex, thereby leading to target mRNA decay.23,24 Importantly, ASOs can also alter the biological properties of proteins by binding to pre-mRNAs to make the splicing signal invisible to the spliceosome, thereby modulating splicing decisions such as exon skipping and exon inclusion.25,26

Single-stranded ASOs are unstable against intracellular nuclease degradation and are strictly complementary to target RNAs. These properties indicate that the ability to optimize the properties of ASOs via sequence variation is limited. Thus, chemically modified nucleotides or specific sequences are incorporated to increase the binding affinity and resistance to nuclease degradation of the ASOs.27 In addition, ASOs tolerate more extensive chemical modifications in the gapmer without abrogating the activity of RNase H1.28 The detailed chemical modifications of ASOs will be introduced in the next section.

Aptamers

Aptamers are short single-stranded nucleotides with unique tertiary structures, typically 20 to 100 nucleotides of DNA or RNA.29 Aptamers have diverse secondary structures, such as hairpins, internal loops, bulges, pseudoknots, and G tetramers.30 Aptamers can recognize, bind and subsequently block target molecules with high affinity, working like antibodies.31 Compared with in vivo synthesized antibodies, aptamers have the advantages of a low cost, low immunogenicity, a short synthesis time and high specificity.32 Additionally, due to their flexible nature, aptamers can be designed to bind even hidden epitopes, which is impossible for antibodies.33 Generally, high-affinity aptamers are selected from random libraries using an in vitro procedure called systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX).34 The basic process of SELEX is a repeated cycle of four steps: incubation, binding, elution of the bound target and amplification. First, a random oligonucleotide sequence library is incubated with the target molecule. During incubation, some sequences bind to the target molecule, whereas others bind weakly or do not react. Then, through partitioning and washing, lower affinity aptamers and unbound sequences are removed from the solution, whereas bound aptamer molecules are eluted. The eluted sequences are subsequently amplified for the next round of selection. After 5–15 rounds, a rich pool of aptamer candidates can be obtained for experimental evaluation and further optimization to obtain the final mature aptamers. However, traditional black box approaches such as SELEX run the risk of being unable to develop the best aptamer for a specific target.34 Thus, researchers have developed more advanced methods for consistently producing high-performance aptamers. For example, Gotrik et al. designed the microfluidic device SELEX and high-throughput sequencing SELEX, and the results revealed that after these alterations, higher-affinity aptamers can be obtained after far fewer rounds of selection relative to conventional methods.35 Capillary electrophoresis allows separation in free solution, and its participation in SELEX can greatly reduce the selection time and selection cost.36 Ishida et al. presented a novel method, RNA aptamer Ranker (RaptRanker), to identify optimal aptamers from HT-SELEX data by scoring and ranking. Through an evaluation, they proved that the performance of RaptRanker was superior to that of conventional methods, such as frequency, enrichment and MPBind.37

siRNAs

siRNAs are double-stranded RNA molecules consisting of 20–25 base pairs, with two nucleotides overhanging at the 3’ ends. Each molecule possesses a 5’ phosphate and a 3’ hydroxyl group.12,38 There are two strands of siRNA, one is guide strand (also called antisense strand), which can guide nuclease to cut the target gene; the other one is passenger strand (also known as sense strand). After the introduction of double-stranded siRNA into cytoplasm, the Argonaute 2 protein (AGO2) clears the passenger strand, releasing the guide strand, forming an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) with Dicer and transactivation response RNA binding protein (TRBP).39,40,41,42,43 A success RNAi initiation is owing to the correct selection of guide sense by Dicer, possessing ability of asymmetrical recognition, since the passenger sense is incapable in RNAi activation.40,44 TRBP maintains a proper orientation for the guide strand to bind to AGO2 because of its high flexibility. After the guide strand binding with specific mRNA, the target mRNA is cleaved, a process mediated by AGO2 that occurs between the 10th nucleotide and the 11th nucleotide from the 5′-most of paired sequences.45,46,47,48 Broken mRNA is unable to maintain the structural stability and subsequently degraded, resulting in target gene downregulation.

Initially, siRNA sequence selection was based on experimental insights, but bioinformatic methods are now used to aid in siRNA design. Key principles in siRNA design include targeting the coding sequence (CDS) or 3’ untranslated regions (UTR) and avoiding the 5’ UTR; ensuring no complementarity with nontarget mRNAs or homology with sequences from other species49; preferring 21-nt siRNAs with 2-nt 3′ overhangs and necessary 5′ phosphates50,51; avoiding overly long dsRNAs to prevent mRNA degradation failure and apoptosis52,53,54; preventing secondary structure formation in the guide strand55; maintaining a G-C content between 30% and 52%56; ensuring strand asymmetry, where the 5′ end of the guide strand is less stable and having U or A57,58; avoiding U-rich or GU-rich sequences in the guide strand to reduce immunogenicity59,60,61,62; and considering deoxyribonucleotide (TT) substitutions for 3′ overhangs to lower the synthesis costs.47

miRNA

The mechanism by which miRNAs silence gene expression is similar to that of siRNAs. Several steps are needed for endogenous miRNAs to progress from primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) to mature miRNAs. First, pri-miRNAs are transcribed from miRNA genes with RNA polymerase II in the nucleus.63 DGCR8 helps cleave pri-miRNAs at approximately 11 bp from the junction with Drosha, creating hairpin pre-miRNAs with 60 to 70 nucleotides, called pre miRNAs.64 Then, these pre-miRNAs are exported to the cytoplasm by the EXP5 complex and further processed into shorter double-stranded duplexes by Dicer.65 One strand (miRNA*) of the duplexes is stabilized in Argonaute to form the miRISC and the other strand (miRNA) is expelled.63,66,67,68 Finally, miRISC targets mRNAs, typically at the 3′-UTR, through seed sequence hybridization, leading to mRNA translational inhibition or decay. On the one hand, guide strand miRNAs that have perfect complementary pairing with their mRNA targets induce mRNA cleavage and subsequent degradation; on the other hand, miRNAs that have imperfect complementary pairing with their mRNA target repress mRNA translation through steric hindrance, resulting in target gene silencing.69 Unlike rigid siRNAs, a single miRNA duplex can simultaneously bind to different mRNAs, regulating the expression of multiple proteins, as more than half of the human genome contains numerous miRNA binding sites.70 Although abundant microRNAs are considered negative regulatory noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) that function in the cytoplasm, emerging evidence shows that there are also some miRNAs in the nucleus.71,72,73 More unexpectedly, Xiao et al. reported a set of miRNAs located in the nucleus possessing gene-activating function. In their research, they found that miR-24-1, a member of theses miRNAs, can bind to enhancers of RNA transcripts, increasing expression of the target gene.74 The most commonly used miRNA drugs in the clinic are still miRNA mimics, whose sequences mirror those of natural endogenous miRNAs to downregulate the expression of target genes.

Since the sequences of miRNA mimics are exactly the same as those of natural miRNAs, modifying their sequences is challenging. However, key principles in miRNA mimic design have been identified. First, the mimics should involve two incompletely paired strands, as double-stranded miRNA mimics exhibit significantly greater efficacy in gene silencing than single-stranded mimics do, by approximately 100–1000-fold.75 Additionally, variations in the length of pre-miRNAs may affect Dicer cut site selection, potentially altering the miRNA seed sequence and influencing guide strand selection.76 Ideal length for miRNA mimics is 22 base pairs, matching that of mature endogenous miRNA duplexes. This length not only enhances the ease of delivery and reduces costs but also ensures optimal efficacy. Moreover, the seed and 3′ regions of synthesized miRNAs should be enriched with AU sequences to prevent strong binding between the target RNAs and the 3′ regions of guide strands.77,78

piRNAs

piRNAs are a class of single-stranded small noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) with a length of 26–31 nucleotides.79 The concept of piRNAs was introduced in July 2006. Several research groups almost simultaneously reported that a new class of ncRNAs typically binds to PIWI proteins, resulting in the silencing of transposable elements, which is distinct from the mechanisms for siRNAs and miRNAs. PIWI, a subgroup of Argonaute proteins, is expressed mainly in the reproductive system.80,81,82,83 Endogenous piRNAs are processed from piRNA-coding sequences, which are predominantly grouped into 0.4–73.5 kilobase clusters occurring in the intergenic regions of chromosomes with highly uneven distributions.84 piRNA clusters are processed into mature piRNAs through several steps. The piRNA clusters are transcribed to primary piRNAs (pri-piRNAs) by RNA polymerase II in the nucleus, similar to the process of miRNAs. Single-stranded pri-piRNAs are subsequently transported to the Yb body in the cytoplasm for further slicing with Zucchini (Zuc).85 The sliced 5′ fragment subsequently binds to the PIWI proteins, forming an intermediate-piRNA-PIWI complex. After the 3′ end is trimmed to the optimal length and the 2′-hydroxy group at the 3′-end is methylated, the mature piRNA-PIWI complex migrates back into the nucleus to block target gene transcription.86 In addition to the primary processing pathway described above, mature piRNAs can be amplified through a “ping-pong” cycle. In addition to PIWI proteins, mature piRNAs can also bind to AGO3 (sense transcription) or AUB (antisense transcription). The resulting piRNA-AGO3/AUB complex can target pri-piRNAs and cut them into new mature piRNAs for the next cycle.87 Numerous studies have shown that piRNAs can regulate the differentiation and development of germ cells through transposon inhibition.88,89,90,91,92,93 In general, three major pathways by which piRNAs regulate gene expression have been identified. piRNAs can form a piRNA-induced silencing complex (piRISC) with PIWI proteins, resulting in transcriptional gene silencing in the nucleus and posttranscriptional gene silencing in the cytoplasm.94 In the PIWI cleavage process, mismatches to any target nucleotide can be tolerated, including those flanking the scissile phosphate.95 Additionally, piRISC can also bind to proteins to promote interactions with multiple proteins.96

Although most studies of piRNAs are focused on mechanistic research and rarely on gene regulation therapies in preclinical studies or clinical trials, growing evidence indicates that piRNA predominantly regulates the occurrence and progression of cancer cells, particularly in terms of proliferation, migration, metastasis, and apoptosis.97 piRNAs act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors by regulating factors in tumor-related signaling pathways. For example, piR-651 is upregulated in various human solid cancers, where its overexpression promotes cell proliferation and invasion, suppresses apoptosis, and decreases G0/G1 phase arrest, accompanied by increased expression of oncogenes such as MDM2, CDK4, and Cyclin D1.98 In contrast, piR-823 is expressed at significantly lower levels in gastric cancer tissues compared to non-cancerous tissues. Additionally, piR-823 interacts with PINK1, enhancing its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thereby suppressing mitophagy during tumor development.99,100 Thus, targeting piRNAs presents a promising therapeutic strategy. Emerging studies suggest that piRNAs could be leveraged to modulate pathways that contribute to tumorigenesis, presenting new avenues for therapeutic intervention. For example, the downregulation of PIWIL1 and piR-DQ593109 enhanced BTB permeability via the MEG3/miR-330-5p/RUNX3 axis, providing valuable insights for glioma therapy.101 Another successful application is the upregulated expression of piRNA-36712, which shows a synergistic anticancer effect when combined with chemotherapeutic agents in breast cancer cells.102 However, delivering piRNA in a manner that is specific to organs remains a challenge to minimize off-target effects. Further research is needed to fully characterize the mechanisms through which piRNAs operate in different cancer types. Exploring the therapeutic potential of piRNA-based treatments, including the design of piRNA mimics or inhibitors, could lead to innovative cancer therapies with improved specificity and reduced side effects. Collectively, piRNAs offer a promising new frontier in cancer research, with the potential to be developed into targeted therapies that address both the prevention and treatment of cancer by leveraging their unique role in maintaining genomic stability and regulating key oncogenic pathways.

saRNAs

saRNAs are double-stranded RNAs consisting of 21 nucleotides, with 2 nucleotides overhanging at the 3’ end, which can increase the expression of target genes by RNA activation (RNAa).103,104 After introduction into the cytoplasm, the saRNA duplex binds to AGO2 and unwinds under the action of RNA helicase A (RHA), following an import into the nucleus mediated by importin-8.105,106,107,108,109 The guide strand then leads the complex to bind with target promoters, recruiting the polymerase-associated factor 1 (PAF1) complex to assemble the RNA-induced transcriptional activation (RITA) complex.110 Finally, the RITA complex initiates transcription and productive elongation by RNA polymerase II, thus increasing the expression of target proteins.111

The selection of genomic regions is vital in the sequence design of saRNAs. There should be sequences in the saRNAs which can complementary with the promoters or 3’ terminus of target genes.112 The target region should not be identical to other sequences to avoid off-target effects (OTEs) caused by sequences; the target region should not contain CpG islands or DNA hypermethylation to avoid OTEs caused by special nucleotides.113 Furthermore, every nucleotide is highly important for saRNAs since mutation of the seed region can influence RNAa levels and can even lead to complete dysfunction.114 Additionally, single-stranded saRNAs have no effect on gene expression activation, indicating that the presence of an intact duplex RNA is essential.115

Compared with the downregulation of genes triggered by siRNAs and miRNAs, the activation of gene expression induced by saRNAs lasts much longer, approximately 2 weeks, than that induced by other agents and is 7 days long.113 However, a greater concentration (nM) of saRNA therapeutics is required to achieve therapeutic effects, whereas siRNAs can act at a relatively low concentration (pM–nM).116 Compared with mRNAs, saRNAs offer advantages in mass production because of their lower nucleotide count, resulting in substantially lower costs. Moreover, the smaller size of saRNAs may pose fewer delivery challenges than those posed by the larger size of mRNA molecules. Additionally, saRNAs tap into the gene regulatory machinery of endogenous cells to activate gene expression, reduces the risk of detrimental overexpression and immunogenicity, a common challenge encountered with mRNAs.117

In summary, although some differences exist among the six types of small nucleic acid therapeutics, they all make great efforts to rescue the disordered gene expression of targets that were previously considered undruggable. Although the rational design of a nucleic acid sequence can increase its potency, chemical modification is a much more powerful strategy.

Modification of nucleic acids

Since unmodified naked nucleic acids that are intravenously injected into the target tissue can be rapidly degraded by RNases and cleared from the blood, chemical modification is crucial for generating effective nucleic acid drugs.118 The key goals for chemical modification include increasing the binding of small nucleic acids with target sequences, enhancing nuclease stability, optimizing pharmacokinetic characteristics, and minimizing side effects.119,120 To date, a lot of effort has been made in modification of small nucleic acids (Fig. 4).121

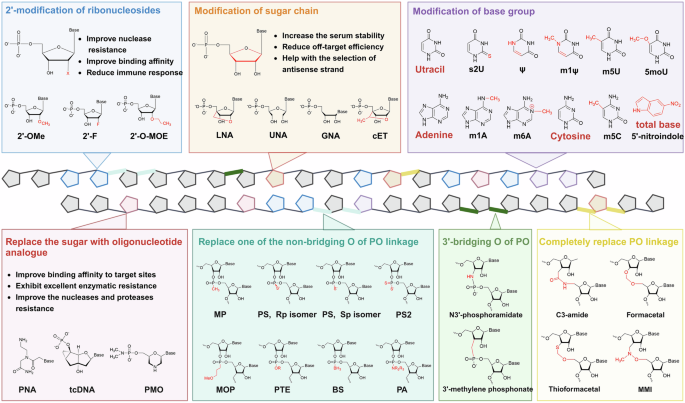

Chemical modifications used for small nucleic acids. Common modifications can be divided into three categories: ribosome modifications, nucleobase group modifications and backbone modifications. Modifications of ribosomes are always performed on the 2’ ends of ribose sugars (blue box) and sugar chains (orange box). In modifications of the base group, uracil, adenine and cytosine are the common objects (purple box), and the ribose sugar can be completely replaced (red box). The PO linkage of the backbone can be changed, including the nonbridging O atom (cyan box), 3’-bridging O atom (green box) and total PO linkage (golden box), to reduce the net anionic charge of small nucleic acids

Structural modification of nucleic acids

The structure of ribonucleotides can be altered by chemically modifying nucleotide bases, sugar moieties, or nucleosides. Widely used 2’-sugar modifications include 2ʹ-fluoro (2ʹ-F), 2ʹ-O-methyl (2ʹ-OMe) and 2ʹ-O-(2-methoxyethyl) (2ʹ-O-MOE), all of which have been proven to be effective and accessible to the market.122,123,124,125,126 In addition to adding modifications at the 2’ position of ribose, changing its structure is also feasible. RNAs with ribose structural modifications include constrained ethyl (cEt), glycol nucleic acids (GNAs), locked nucleic acids (LNAs; also known as 2′,4′-bridged nucleic acids, BNAs), nucleosides and tricyclo-DNA (tcDNA) and unlocked nucleic acids (UNAs). cEt nucleosides are similar to LNAs in structure with an additional methyl group.127 GNAs are acyclic nucleic acid analogs, which can result in greater thermal destabilization of the duplex structure.128 There is a methylene bridge to connect the 4′-carbon with 2′-oxygen of LNAs, which can both increase the serum stability and reduce the off-target effects.129 UNAs are 2′,3′-seco-RNAs that always used to disrupt the stability of double-stranded RNA.130 Another common strategy involves modifying the base group of nucleotides, such as replacing uracil with pseudouridine (Ψ),131 N1 methylpseudouridine (m1 Ψ),132 5-methyluridine (m5U),133 5-methoxyuridine (5moU)134 or 2-thiouridine (s2U)135; using N1-methyladenosine (m1 A)136 or N6-methyladenosine (m6 A)137 instead of adenine; and methylating cytosine to 5-methylcytidine (m5C).138 Moreover, the base group can be directly replaced with a nitroindole, an universal base to decrease undesired off-target effects.139 Through the addition of oligonucleotide analogs to nucleic acids, such as tcDNA, a conformationally constrained oligonucleotide analog140; PMO, which replaces the pentose sugar with a morpholine ring; phosphate141; peptide nucleic acids (PNAs), enhance both the selectivity and thermal stability of the compounds to increase the binding to target RNAs.142

Backbone modifications

Reducing the net anionic charge of oligonucleotide drugs and increase the delivery efficiency.143 A common strategy is to replace one of the nonbridging oxygen atoms of the phosphodiester bond (PO linkage) with a nonionic modification group,137 such as phosphorothioate (PS),144 methylphosphonate (MP),145 methoxypropyl phosphonate (MOP),146 phosphorodithioate (PS2),147 phosphoramidate (PA),148,149 phosphoroselenoate (PSe),150 phosphotriester (PTE)151 or boranophosphate (BS).152 Likewise, the 3′-bridging oxygen atoms of the PO linkage can be replaced with carbon or nitrogen to form 3′-methylene phosphonate or N3′-phosphoramidate, respectively.153,154 In fact, the PO linkage can be completely replaced. The trans isomers of amides preorganize sugars into C3′-endo conformations; thus, the C3-amide modification (3’-CH2-CO-NH-5’) increases the biological activity of nucleic acids.155 Methylene (methylimino) (MMI) is another nitrogen that contains an achiral four-atom linkage (3’-CH2N(CH3)-O-5’) and is completely resistant to nucleases.156 Apparently, the hydrophobic formacetal linkage (3’-O-CH2-O-5’) exhibited increased stability in all the RNA duplexes, whereas it strongly destabilized the DNA helix.157 Thioformacetal, which replaces the 3′-sided oxygen atom with a sulfur (3’-S-CH2-O-5’), increases both the stability of nucleic acids and the affinity for target RNA.158 Among these modifications, PS is the most commonly used. The PS linkage has chemical properties similar to those of the PO linkage, but it can greatly increase the metabolic stability of small nucleic acids and protect them from rapid degradation.159 In addition, there are two isomers of PS linkage, including right-handed (Rp) and left-handed (Sp), possessing different biological properties.160 With the development of synthetic methodologies, stereopure PSs with only one isomer are possible. However, whether nucleic acid drugs with stereopure PSs possess superior potency, efficiency and durability is still unclear since this topic has been highly debated for several years.161,162,163,164

In the early days of the chemical modification of nucleic acid drugs, primary agents were synthesized, and recent studies have shown that their combination with nucleic acids and the backbone has excellent potency. Wu et al. combined PS2 with 2’-OMe in a same nucleotide (MePS2), results showed enhanced resistance to nucleases degradation for siRNAs.165 Baker et al. suggested that introducing LNAs into splice-switching oligonucleotides, which have been modified with phosphorothioates, increases the activity of nucleic acids due to their reduced charge.166 Notably, though these chemical modifications showed robust efficiency and well tolerance in a broad of researches, there are some side effects occurred in the clinic.167 For example, PS-modified oligonucleotides lead to unexpected binding to platelets, thus forming thrombus.168 Moreover, LNAs can induce hepatotoxicity consistent with acute liver injury in as little as 4 days, which might be caused by two trinucleotide motifs, TCC and TGC.169,170 Safe and efficient chemical strategies should be a focus for the development of future nucleic acid therapeutics.

Nucleic acid delivery system

Although rational sequence design and chemical modification of nucleic acids can increase their stability and reduce OTEs, targeted delivery to specific cells and organs remains a great challenge. Ideal delivery systems are expected to possess high drug loading efficiency and sufficient safety, protect nucleic acids from rapid degradation and specific targeting. In the following sections, we describe the major nonviral delivery systems used for small nucleic acids (Fig. 5).

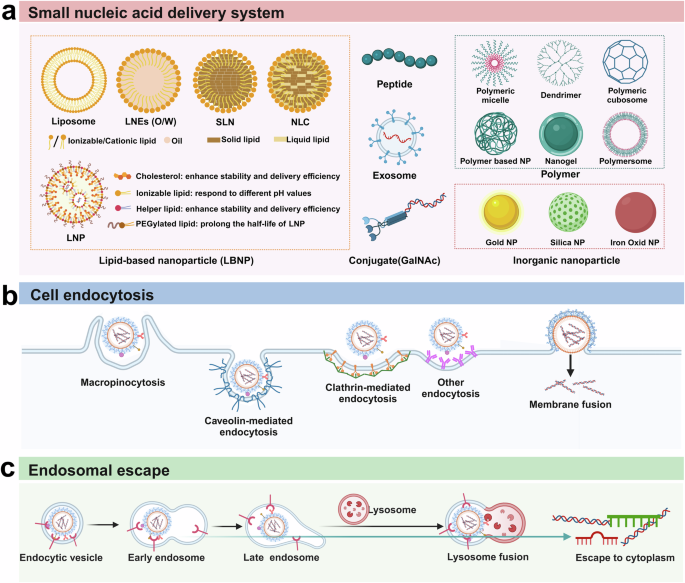

Technologies for the delivery of small nucleic acids. a The six types of common nonviral delivery vectors include lipid-based nanoparticles (LNPs), polymers, peptides, exosomes, conjugates (GalNAc) and inorganic nanoparticles. b Schematic diagram of small nucleic acid drug uptake pathways by target cells. There are four major endocytosis pathways, including macropinocytosis, caveolin-mediated endocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis and direct membrane fusion. c Schematic diagram of endosomal escape. After internalization, endocytic vesicles develop into early endosomes and late endosomes and subsequently fuse with lysosomes to induce lysosomal degradation. Only a small fraction (usually less than 1%) of small nucleic acids can escape from the endosome to the cytoplasm

Lipid-based nanoparticles (LBNPs)

LBNPs are spherical nanoparticles with favorable biocompatibility and degradability and are currently the most promising delivery carrier. LBNPs can be divided into five categories according to their compositions: liposomes, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), lipid nanoemulsions (LNEs), solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs).

Liposomes

Classic liposomes consist of cholesterols and amphiphilic phospholipid bilayers encapsulating an aqueous inner compartment, with sizes ranging from 100 nm to 5 μm, which is quite similar to the size of the natural cell membrane.171,172 The amphiphilic phospholipid has a hydrophobic tail group and a hydrophilic head group, which are oriented to the outer and inner sides in the composition of liposomes. Liposomes can be divided into 2 types according to their basic structures: unilamellar liposomes with single bilayer membranes and multilamellar liposomes containing multiple bilayer membranes.173 Liposomes were first discovered in 1961. Bangham and Horne reported that phospholipids dispersed in excess water could form closed vesicles composed of bimolecular membranes, and images captured with an electron microscope were published in 1964.174 In 1971, Gregoriadis et al. first constructed liposomes composed of phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol and diacetyl phosphate as enzyme drug carriers. The results revealed no measurable leakage of the encapsulated albumin, and most of the albumin accumulated in the liver.175 Since then, liposomes have been widely used as drug delivery systems.176,177,178 Yano et al. complexed siRNA-B717, which targets the human Bcl-2 oncogene, with a novel cationic liposome, LIC-101, containing 2-O-(2-diethylaminoethyl)-carbamoyl-1,3-O-dioleoylglycerol and egg phosphatidylcholine and intravenously injected into mice with liver metastasis and subcutaneously injected into prostate cancer-bearing mice (inoculated under the skin). In both models, the complex showed strong antitumor activity.179 However, cationic nanocarriers are reported to induce cellular necrosis, especially in the lungs, upon systemic administration.180 Changing the electric charge of liposomes could be a promising strategy. Qian et al. employed hyaluronan (HA) to negate the positive charge of liposomes since HA is an anionic polysaccharide with a negative charge. Through in vitro and in vivo tests, HA-modified liposomes were shown to exhibit reduced toxicity and a comparable transfection efficiency to unmodified liposomes.181 In addition, Villares et al. constructed neutral liposomes with neutral 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), which can simultaneously improve the tumor uptake efficiency of nucleic acid‒liposome complexes. Their results first revealed the effective inhibition of melanoma growth and metastasis in melanoma-bearing mice after systemic treatment with the protease-activated receptor-1 siRNA-DOPC complex.182

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)

LNPs are the most advanced clinical delivery vehicles,183,184,185 currently showing strong potential for nucleic acids delivery in gene therapy.186 In addition to GalNAc-modified siRNAs, LNPs are the only small nucleic acid carriers approved by the FDA for the targeted delivery of siRNAs.187 The unique property of LNPs is their neutrally charged surface, which enables them to avoid extensive adsorption by serum proteins and prevent poor penetration into the target tissue.188,189 Unlike liposomes, LNPs contain multiple reverse micelle nuclei composed of nucleic acids and lipids, which are surrounded by a monolayer lipid membrane.190 Four primary lipids are used to form the shells of LNPs, namely, ionizable lipids, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-modified lipids, cholesterol and helper phospholipids, which are present in suitable proportions (commonly known as molar ratios of 50, 1.5, and 38.5/10, respectively).191 The composition of the LNP shell is quite important in the physicochemical properties and functions of LNPs, and the optimal ratio can vary under different conditions. Each lipid in the LNP shell plays a different but similarly essential role in effective small nucleic acid delivery. Ionizable lipids are the major component of LNPs because of their potency. Ionizable lipids can ensure that the surface of LNPs remains neutral at physiological pH, given their precise and appropriate pKa, which is between 6.2 and 6.5, different from previous cationic lipids.192,193 The ionizable lipids can respond to different pH values, remaining neutral at pH 7 but becoming positively charged at lower pH values.193 Therefore, for neutral LNPs, tolerability and safety are further increased by preventing reactions with negatively charged biomacromolecules, which can trigger severe side effects that are unavoidable when permanently charged cationic lipids are used.194 Moreover, a PEGylated lipid is a hydrophilic PEG polymer conjugated to a hydrophobic lipid anchor, with the lipid domain within the polymer structure and the PEGylated domain extending out from the polymer surface.195 PEG can prolong the half-life of LNPs in the circulation, since it can adsorb the serum proteins in blood.196,197,198 However, it can also reduce the proximity of LNPs to cell membranes and inhibit fusion between LNPs and cell membranes, leading to a decrease in nucleic acid uptake efficiency.199 Research has shown that a higher PEGylated lipid content results in a smaller particle size.200 However, the reduced delivery efficiency is driven primarily by an increase in the PEG content rather than by a decrease in the particle size.201 Thus, the optimal dose of PEGylated lipids should be selected to maintain a balance between stability and transfection competency and safety. Cholesterol maintains the stability of the LNP surface while increasing its delivery efficiency since it can fill the gaps between different lipids, reduce the possibility of immune clearance and bind Apo E and LDL receptors to aid in LNP uptake.202,203 The addition of cholesterol analogs and C-24 alkyl phytosterols not only increases the cellular uptake of nucleic acids but also prolongs the retention time after endosomal escape.204 Helper phospholipids, such as 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), are always zwitterionic, which can increase the stability and delivery efficiency of LNPs. Cone-shaped DOPE forms an inverted hexagonal (HII) phase, and cylinder-shaped DSPC can provide greater bilayer stability.205

The most commonly used technology for LNP synthesis is the ethanol dilution method, which uses a microfluidic device. Generally, by mixing a lipid solution dissolved in ethanol and a small nucleic acid solution dissolved in aqueous buffer (pH 4), positively charged ionizable lipids bind to negative nucleic acids and subsequently encapsulate RNAs to form LNPs with other lipids.206 The residual ethanol is then removed from the pH 4 buffer through dialysis, followed by increasing the pH (7.4) for long-term storage and subsequent use.191 The particle size of LNPs is associated with the speed of ethanol dilution with a buffer solution, where more rapid dilution produces smaller LNPs, suggesting that the desired microfluidic device should be able to undergo rapid and controllable mixing.200,207 Detection methods have also improved, thereby improving the quality control of LNPs. For example, Kim et al. developed a robust high-performance liquid chromatography with charged aerosol detector (HPLCCAD), which can quantify the composition of LNPs using the designed approach.208

Research has shown that LNPs enter cells through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and micropinocytosis.209 After internalization, the nucleic acid–LNP complex is transported through early endosomes, late endosomes, and lysosomes, all of which have pH values less than 7.210 Small nucleic acid release occurs mainly in a moderately acidic early endocytic compartment before transport to late endosomes and lysosomes.

However, several hurdles limit the application of LNPs, the majority of which are safe and associated with LNP formulations. Although PEGylated lipids attribute a lot to LNP delivery systems, they are also the causes of various adverse reactions induced by nucleic acid-LNP drugs.211 First, accumulating evidence indicates that PEG can induce hypersensitivity reactions by stimulating the complement system.212,213 Moreover, PEGylated lipids could lead to accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon, reducing their therapeutic efficacy.214,215,216,217 Furthermore, another disadvantage of PEGylated lipids is their nonbiodegradability, suggesting that PEGs should have a relatively low molar mass, generally less than 20 kDa.218,219,220 Additionally, the molar mass should be greater than 400 Da since a lower mass is toxic in humans.221 Many efforts have been made to reduce the side effects of LNP treatment. Judge et al. evaluated LNPs the stabilities of LNPs with different PEGylated lipids, results showed that PEGylated lipids with shorter alkyl chains (C14) are more stable.222 To date, new PEGylated lipids have been preferentially designed, which can disengage from the LNPs after injection via a process called PEG shedding, thus maintaining the advantages of PEGylated lipids and simultaneously avoiding their side effects.223,224 For example, Hatakeyama et al. developed PEG–peptide–DOPE (PPD), showed higher efficiency of cellular uptake and endosomal escape.225 The long-chain PEG 5000 polymer O’-methyl polyethylene glycol (omPEG), which is a pH-sensitive PEG shed from LNPs, has low toxicity to blood and noncancerous intestinal cells.226 In addition, the fate of the nucleic acid–LNP complex is also a noteworthy issue, as nucleic acid–LNP complexes accumulate in large amounts in the liver when they are administered intravenously.227,228,229 The target organs of LNPs can be changed by altering the lipids used to form the LNP shell. For example, DSPC-containing LNPs preferentially accumulate in the spleen, whereas DOPE-containing LNPs preferentially accumulate in the liver, suggesting that different helper lipids should be chosen for different uses of LNPs.230 Additionally, adding a target molecule into an LNP can affect its delivery endpoint. For example, Lee et al. incorporated a Glu-urea-Lys PSMA-targeting ligand into the LNP system, resulting in increased LNP accumulation at tumor sites.231 Ramishetti et al. constructed tLNPs that can specifically deliver nucleic acids to CD4( + ) T lymphocytes by chemically conjugating mAbs against CD4 to the LNPs. After intravenous injection, particles were accumulated in lymph nodes, blood, and bone marrow, and effectively endocytosed by CD4( + ) T lymphocytes.232 Younis et al. designed ultrasmall lipid nanoparticles with a novel pH-sensitive lipid and a targeting peptide, exhibiting excellent tumor accumulation and gene silencing in vivo.233 In addition, by adding polyelectrolyte layers to LNPs, poly-L-arginine and hyaluronan (HA) can cross the BBB, targeting glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells more effectively than unmodified LNPs in vitro and delaying tumor growth in vivo after siRNA and miRNA transfection.234 Altering the administration route might also be a viable option. Bai et al. developed an inhalable and mucus-penetrating LNP system that can significantly diminish fibrosis development.235 Wang et al. constructed lipidoid (lipid-like) nanoparticles to deliver a VEGF siRNA into the eyes through intravitreal administration and treat retinal angiogenic diseases.236 In summary, LNPs show great potential in small nucleic acid delivery.

Lipid nanoemulsions (LNEs)

LNEs are nanosized spherical particles composed of surfactants and phospholipids and are approximately 200 nm in size. The structure of LNEs not only is similar to that of liposomes but also remains biodegradable, biocompatible and nonimmunogenic.237 Three dispersions of LNEs are commonly used—oil in water (O/W), water in oil (W/O) and water in oil in water (W/O/W)—of which O/W is the most commonly used in nucleic acid drug delivery.238 The oil phase of LNEs can protect nucleic acids from degradation by nucleases. Although no proteins are components of LNEs, apolipoproteins, such as ApoA, ApoC and ApoE, can be incorporated into LNEs through contact with plasma in the blood circulation. ApoE can be recognized by the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor, which is overexpressed in some tumors; thus, LNEs can deliver nucleic acids to tumor cells with high LDL receptor expression.239 Changing the proportions of components or directly changing the composition of LNEs could alter their physicochemical characteristics and in vivo biodistribution. By increasing the weight ratio of medium-chain triglycerides to soybean oil from 1:4 to 3:2, Jiang et al. reported that the LNE size decreased from 126.4 ± 8.7 nm to 44.5 ± 9.3 nm. The addition of PEGylation increased the accumulation of LNEs in the tumor area by 6–7-fold.240 Kaneda et al. formulated LNEs consisting of DOTAP, DOPE and cholesterol. These siRNA-LNE complexes can be internalized through lipid raft transport, bypassing the usual endosomal nanoparticle uptake pathway and increasing drug availability.241 Compared with liposomes, the manufacture of LNEs is less expensive. Gehrmann et al. investigated the preparation of LNEs with disposable materials. By changing different syringe filters and pharmaceutically relevant emulsifiers, they finally developed a stable protocol to quickly and easily produce LNEs with narrow particle size distributions.242 Unfortunately, LNEs are more commonly used in the delivery of poorly water-soluble, highly lipophilic drugs but not hydrophilic nucleic acid drugs, as their oil phase can solubilize these drugs.243

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs)

SLNs are spherical nanoparticles composed of biodegradable physiological lipids and surfactants with a drug-containing solid lipid core, and thus they are less toxic than other nanodelivery systems.244 The melting points of the employed lipids, such as monostearin, stearyl alcohol, stearic acid, glycerol monostearate and Precirol® ATO5, are above room temperature.245 Unlike LNEs, organic solvents are not used in the preparation of SLNs, which may introduce potential toxicity.246 Interestingly, Shirvani et al. produced a novel type of SLN using natural beeswax and propolis wax, both of which are considered food grade.247 SLNs are stable in biological fluids and during storage for at least one week at room temperature and 1 month at 4 °C.248 Lyophilization can further improve the storage stability of the solid forms of SLNs and retard unfavorable chemical degradation.249 In addition, by coating the surface of SLNs with chitosan, the residence time in the focal area of the drug–SLN complex can be further improved via mucoadhesive interactions.250 The size of LNEs may influence their in vivo distribution. By comparing SLNs with different particle sizes (120–480 nm), Huang et al. reported that a larger particle size led to a longer lung retention time.251 In addition, SLNs are quite easy to sterilize and mass produce.252,253

However, some obstacles prevent SLNs from delivering nucleic acids. For example, during the solidification process, the inner loaded nucleic acids might be excluded from the surface of SLNs, which are surrounded by an aqueous phase, resulting in an insufficient loading efficiency.254 In addition, during storage, SLNs are prone to aggregate and gelatinize.254

Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs)

NLCs contain a lipophilic core formed by a mixture of one solid lipid (in a greater quantity) with one liquid lipid (in a lower quantity).255 NLCs are recognized as second-generation SLNs, which address their limitations. First, liquid lipids are added to the solid lipid matrix of SLNs to disrupt the perfect crystal order, thereby stabilizing the LNEs and preventing loaded nucleic acid leakage during storage.256 By adjusting the ratio of liquid lipids to solid lipids, NLCs can also maintain a solid skeleton structure at room temperature for a long period, which is conducive to the controlled release of loaded nucleic acids.257 In addition, the payload of NLCs is increased, and the bioavailability of loaded nucleic acids is further improved.258 Because of these alterations, NLCs are more suitable for carrying biologically active ingredients.259 However, relatively few studies have investigated the use of NLCs for small nucleic acid delivery. Oner et al. successfully prepared 13 NLCs with characteristics similar to those of their precursor SLNs, but not all of these NLCs could form complexes with siRNAs.260 More detailed information about the LBNP system mentioned in this section is listed in Table 1.

Peptides

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) and homing peptides consist of 5–30 amino acids and interact with biomolecules and cells to increase nucleic acid delivery efficiency.261 Compared with viral carriers, peptides of varying sizes and structural features have the advantages of a greater payload capacity and biocompatibility and have broad applications.262 Moreover, rationally designed peptides can overcome a series of biological obstacles, such as endosomal escape, cell internalization, and interactions with biomolecules and cells, to improve nucleic acid delivery efficiency. The side chains of these materials can carry various active functional groups that can be chemically modified to enhance the drug delivery systems. In addition, peptides can also be integrated as functional fragments into drug delivery systems.

CPPs and intracellular targeting peptides are of particular interest because they can improve the delivery efficiency of gene therapies into cells. CPP also known as a protein transduction domain (PTD), is a kind of membrane-active peptide that typically contains 5–30 amino acids. CPPs were initially designed to mimic the transactivator of transcription (TAT) protein transduction domain,263 penetratin,263 and Pvec,263 which can cross cellular membranes via energy-dependent or -independent mechanisms without interacting with specific receptors.264 Nucleic acids are attached to CPPs via covalent bonds or noncovalent complex formation.265 Noncovalent complex formation depends on electrostatic and/or hydrophobic interactions between negatively charged cargoes and positively charged CPPs, protecting bioactive conjugates from proteases or nucleases.265,266 Moreover, peptides can covalently interact with nucleic acids to produce conjugated molecules, and this method is suitable for generating neutral nucleic acids.267 Additionally, functional peptide fragments can be coupled to nucleic acids for delivery through chemical bonds (such as ester bonds, disulfide bonds, and thiol maleimide bonds). Peptide‒nucleic acid coupling molecules have specific structures, molecular weights, and high stability, with an excellent degree of reproducibility.268 CPPs are classified into three major categories according to their physicochemical characteristics: cationic, amphiphilic, and hydrophobic. Numerous preclinical evaluations of CPP-derived therapeutics have been performed to address major unmet medical needs (Table 2).

Cationic CPPs are typically short (up to 30 amino acids) and rich in arginine and lysine residues that have positive net charges.269 The positive charge of cationic peptides is attracted to negatively charged membrane constituents, enhancing the interaction of CPPs with the cell membrane to initiate transport.270 The TAT protein transduction domain was first identified in the HIV genome and is the first and most studied type of CPP. After the discovery of the TAT peptide, additional CPPs, such as Pep-1, polyarginine, and penetratin, were discovered.271,272 The structural prerequisites for the cellular uptake of cationic CPPs have been widely examined in various studies. For example, after cholesterol modification, the DP7 peptide (DP7-C) has shown significant potential because of its unique properties and effectiveness in facilitating cellular uptake.273,274,275,276,277 It can be conjugated with various nucleic acids, including siRNAs and miRNAs, enhancing the stability and bioavailability of nucleic acids.275,276,277 This broad applicability allows DP7-C to be used in a variety of therapeutic settings, treating numerous diseases and conditions.275,276,277 However, the precise mechanisms by which cationic CPPs enter the cell membrane are complex and debated. Arginine-rich CPPs are taken up by lipid raft-dependent macropinocytosis, independent of caveolar, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and phagocytosis.278 Other studies suggest they may directly cross the membrane via transient pores.279 Recently, arginine-rich CPPs were shown to go through vesicles and live cells via vesicular fusion induced by calcium influx, similar to the mechanism of membrane multilinearity and fusion.

Peptides with both polar and nonpolar regions are known as amphipathic CPPs, typically classified as primary, secondary, or proline-rich peptides.280 Primary amphipathic CPPs are chimeric peptides formed by covalently attaching a hydrophobic domain to a nuclear localization signal (NLS), enhancing their ability to target cell membranes effectively. The peptide carrier MPG, derived from the fusion peptide domain of the HIV-1 gp41 protein combined with the nuclear localization sequence of the SV40 large T antigen, efficiently delivers siRNAs into mammalian cells.281 Furthermore, a refined and shorter variant of the amphipathic peptide carrier MPG, called MPG-8 (AFLGWLGAWGTMGWSPKKKRK), enhances the efficiency of siRNA delivery both in vitro and in vivo, without triggering an immune response.282 In a mouse xenograft tumor model, stable and noncovalent nanoparticles were generated with a cyclin B1 siRNA to block tumor cell proliferation and tumor growth.282 Additionally, peptide transduction domain–dsRNA binding domain (PTD-DRBD) fusion proteins efficiently deliver siRNAs.283 In vivo delivery of EGFR and Akt2 siRNAs via PTD-DRBD triggered apoptosis specifically in tumor cells and prolonged survival in mice bearing glioblastoma.284 Moreover, secondary amphipathic α-helical CPPs feature a highly hydrophobic patch on one side, whereas the other side can be cationic, anionic, or polar.285,286 In an interesting study, the siRNA delivery efficiencies of cationic and amphipathic CPPs were compared, and the results revealed that the amphipathic CPPs are more suitable as carrier moieties for delivering siRNA polyplexes.287 In addition to MPG and Pep-1, other known primary amphipathic CPPs are derived from natural proteins. These CPPs include an 18-amino acid-long peptide originating from vascular endothelial cadherin (pVEC),288 a 22-amino acid-long peptide derived from the N-terminal region of p14ARF, named ARF (1–22),289 and a peptide sourced from the N-terminus of the unprocessed bovine prion protein (BPrPr).290 Secondary amphipathic CPPs typically display a unique structure, adopting an α-helical conformation wherein hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids are segregated onto separate faces of the helix.291 The use of secondary amphipathic CPP-based delivery systems provides therapeutic carriers with high delivery efficiency and no cytotoxicity or immunogenicity. Model amphipathic peptide (MAP) is a well-studied CPP featuring an α-helical structure with hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues arranged on opposite sides of the helix.292 Comprising a sequence of alanines, leucines, and lysines (KLALKLALKALKAALKLA),292 MAP has been shown to be an effective carrier for delivering siRNA into cells.293,294 CADY is a 20-residue peptide that adopts a helical conformation within cell membranes and forms stable complexes with siRNAs.291,295 Another type of amphipathic CPPs contains proline-rich CPPs. Although these CPPs vary in sequence and structure across different families, they all feature a proline pyrrolidine template.296,297,298 Apidaecin and oncocin belong to this group of peptides and can permeate the BBB in mice.299,300 PR39 is a proline- and arginine-rich peptide implicated in wound healing and protection against myocardial ischemia.301 PR39 has been utilized as an innovative carrier for delivering siRNAs into the cell cytoplasm, and loading a Stat3 siRNA has shown synergistic effects in suppressing the invasion and migration of 4T1 cells.302

Hydrophobic CPPs with a low positive or negative net charge tend to have poor solubility and easily aggregate.303 Hydrophobic CPPs have recently received increasing amounts of attention due to the extensive presence of positive charges that cause cationic CPPs to be toxic.304 For example, natural C105Y, its C-terminal portion (PFVYLI), and Pep-7 are part of this group, and the affinity of their nonpolar amino acids for the hydrophobic domain of cell membranes aids in their translocation.305,306,307 Several modified peptides can also be generated using various approaches.308 The chemically modified hydrophobic CPP TP10 has four cationic amino acid (Lys) residues among the many hydrophobic amino acid residues, enabling efficient delivery of a splice-correcting 2’-OMe RNA oligonucleotide.309 Therefore, hydrophobic CPPs hold significant potential for the noncovalent delivery of negatively charged oligonucleotides.

Although the groundbreaking and versatile peptide tools have received heightened interest in their application within gene therapy, peptide nanocarriers must be tested in clinical trials before they can be applied in clinical settings. Therefore, additional basic science and preclinical studies are needed to accelerate peptide-based vector development.

Polymers

Since the first human trial approval (NCT01644890) was obtained in the early 1990s, polymeric drugs have entered the market as potent therapeutics.310,311 Innovative polymer-based drug delivery systems have gained significant interest in gene therapy. The polymers employed for gene delivery differ greatly in terms of molecular weight, structure, and composition.312 With linear, branched or dendritic structures, these polymers electrostatically bind negatively charged nucleic acids through their inherent proton sponge behavior, offering protection and promoting cellular uptake.312,313,314 Further chemical modifications of polymers optimize the transfection efficiency, biocompatibility, cell selectivity, and in vivo distribution and reduce cytotoxicity.313,315 In general, synthetic and natural polymers are completely distinct. Polymers derived from natural sources, such as plants, animals, and microorganisms, have the advantages of biocompatibility, mechanical properties, biodegradability and renewability, whereas synthetic polymers are easier to generate and modify and have been widely utilized in all applications due to their structural and mechanical properties; however, they are unable to perform certain biological functions.316,317,318 One of the first widely utilized polymers in gene delivery was polyethyleneimine (PEI), has shown great potential for transfecting dividing cells.319 Regrettably, its cytotoxicity has restricted its application in vivo and in clinical trials, as it has been found to cause membrane damage and initiate apoptosis in clinically relevant human cell lines.320 Currently, a range of polymers, such as poly(b-amino esters), poly(amido ethylenimines), and dendrimers, have emerged,321 demonstrating high transfection efficiency and low cytotoxicity (Table 3).322,323,324,325,326,327,328

Poly(L-lysine) (PLL)

Poly-L-lysine (PLL), synthesized from L-lysine found in high-protein foods like meat and eggs, has inherent properties of non-toxicity, non-antigenicity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability.329,330 As a cationic polymer, PLL can be protonated in physiological conditions, allowing it to electrostatically bind with negatively charged nucleic acids and form complexes.331 Although PLLs are biodegradable, their high degree of cationic toxicity limits their use in nucleic acid drug delivery.322,332 Chemical modifications, such as the introduction of polyethylene glycol (PEG), have been implemented to reduce the toxicity and increase the transfection efficiency of PLLs and thus improve their gene delivery performance. For instance, Kazunori Kataoka’s group developed a PEG-block-poly(L-lysine) (PEG-b-PLL) that features lysine amines modified with 2-iminothiolane (2IT) and the cyclo-Arg-Gly-Asp (cRGD) peptide at the PEG terminus.333 This modification of PEG-b-PLL resulted in better control over micelle formation and enhanced siRNA stability in the bloodstream; subsequently, the incorporation of siRNA into these micelle structures increased cellular uptake, improved the gene silencing efficacy of the siRNAs and increased drug accumulation in both the tumor tissue and tumor-associated blood vessels following intravenous injection.333 This successful application of the PLL modification potentially expands the utility of polymer-based siRNA therapies for cancer treatments that require intravenous injection.333 Dendritic PLL, which allows for the control of molecular size and shape, can also be utilized for gene delivery.334 The 6th generation of dendritic poly(L-lysine) (KG6), with 128 amine groups on its surface, was demonstrated to be an efficient siRNA carrier with minimal cytotoxicity.335 Another star-shaped copolymer consisting of a β-cyclodextrin core and PLL dendron arms was used for docetaxel and MMP-9 siRNA codelivery.336 A biomimetic nanocomplex consisting of a cationic nanocore formed by a membrane-penetrating helical polypeptide (P-Ben) and Sav1 siRNA, a charge-reversal intermediate layer of PLL-cis-aconitic acid (PC), and an outer shell of a hybrid membrane, was administered intravenously. This nanodrug effectively accumulated in the ischemia‒reperfusion-injured myocardium.337 Although polymeric materials are increasingly used in the development of second-generation polymer therapeutics, the applications of PLLs are still relatively restricted compared to other polycations like chitosan (CS), poly(ethyleneimine) (PEI), and poly(amido amine) (PAMAM) and further investigations should explore the development of an appropriate regulatory framework that can be universally applied in research.

PEI

PEI is a synthetic polymer introduced in 1995, featuring an amine group and two CH2 spacers making it a cationic polymer suitable for nucleic acid delivery..338,339 PEI has two distinct chemical structures, namely, branched PEI (BPEI) and linear PEI (LPEI), with molecular weights ranging from 1 to 1000 kDa.340,341 BPEIs contain all types of various primary, secondary and tertiary amines, whereas LPEIs contain only secondary and primary amino groups.341 Interestingly, the capacity of PEI for gene delivery and cytotoxicity are greatly affected by its molecular weight. Therefore, it is important to carefully adjust the PEI structure to balance transfection efficiency and toxicity.342 Qiao et al. developed a successful PEI-siRNA delivery system, the dual siRNA-PEI (siRP) complex locally knocked down the target gene.343 Additionally, SNS01-T is a PEI-based formulation containing two nucleic acids: an siRNA and a plasmid. It has been shown to inhibit tumor growth in various animal models of B-cell cancers and demonstrates acceptable tolerability.344,345 In a Phase I/II clinical trial (NCT01435720), SNS01-T was administered intravenously in multiple doses and dose escalation stages to evaluate the safety and tolerability of the vector in patients with recurrent and refractory B-cell lymphoma. Although the trial was activated in 2011 and was completed in 2014, the results have not yet been published. Only one PEI-based small nucleic acid drug has been tested in clinical trials, highlighting the significant potential of novel PEI-based formulations to overcome current challenges related to drug stability.

Poly(β-amino esters) (PBAEs)

Poly(β-amino esters) (PBAEs) are a promising group of cationic polymers made from acrylates and amines, extensively developed for drug delivery.346,347 PBAEs are pH sensitive and protonated in acidic environments; they can be soluble at acidic pH levels but insoluble at physiological pH levels.348 PBAE-based drug delivery systems primarily enter cells by energy-dependent endocytosis and are split into separate vesicles by lipid bilayers.349 These separate vesicles are internalized into endosomes (pH<5.5), which subsequently transform into lysosomes (pH<4.5).350,351 Various PBAEs, synthesized from different diacrylate and amine combinations, offer diverse physicochemical and mechanical properties for drug delivery.346,352 In recent years, PBAEs have been extensively studied for convenient synthesis, low cost and good biocompatibility, and they can effective at activating antigens and boosting immune responses.353,354,355,356 Bioreducible PBAEs self-assemble with siRNAs in aqueous conditions to form nanoparticles and the ability of simple polymeric nanoparticles to efficiently knock down genes in primary human glioblastoma cells was greater than that of Lipo2000.357 Additionally, synthetic end-modified poly(beta-amino ester) (PBAE)-based nanoparticles can improve siRNA delivery into human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs).358 Although PBAEs were not approved for clinical use following initial human studies, their significant benefits make them promising candidates for medical applications.

Dendrimers

Dendrimers are highly branched, monodisperse, tree-like macromolecules.359 Unlike hyperbranched polymers, dendrimers exhibit random branching and have well-defined and regular nanoarchitectures with spherical shapes.360,361 Moreover, the surface of dendrimers can be chemically modified in multiple ways to alter the functionality of the macromolecules, and the branched nature of dendrimers results in a very high surface-to-volume ratio.362 A relatively empty dendrimer matrix is amenable to host molecule entrapment, facilitating precise, controlled payload release. Dendrimers are prepared via divergent or convergent synthesis.363 The divergent synthesis method has the advantage of modifying the dendrimer molecules starting from the core, whereas the convergent method allows greater control of the modification of molecules at specific positions responsible for specific functions.364,365 Commercially available poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM; Starburstk) dendrimers and poly(propylenemine) (also called PPI, DAB; AstramolR) dendrimers have been most widely studied and applied in drug delivery.366,367 Therapeutic drugs can be encapsulated within the core of PAMAM or conjugated to their surface, facilitating delivery to target cells. The development of covalently bonded hydroxyl-terminated PAMAM dendrimer–siRNA conjugates allows for precise nucleic acid loading, which has been observed using a GFP-targeted siRNA (siGFP) conjugate (D-siGFP).368 Additionally, the conjugation of PAMAM to the thermosome acts as an anchor for siRNAs, and further modification of the protein cage with a CPP increases the delivery efficiency of the siRNA transfection reagents.369 However, the synthesis of dendritic architectures through convergent or divergent methods may disrupt the design and construction, resulting in increased difficulty in mass production. A novel PEG modification strategy that preserves the surface amino groups of polymers has been proposed.370 Catechol-PEG polymers were used to modify the surface of PBA-modified generation 5 (G5) PAMAM dendrimers (G5PBA) via reversible boronate esters.370 This approach maintains the free amines of G5PBA, aiding in siRNA loading, stable complex formation, and increased transfection efficacy in serum.370 PEG-modified dendrimer/siRNA polyplexes show a similar gene silencing efficacy to non-PEG-modified polyplexes under serum-free conditions but superior performance in serum due to PEG shielding.370 In vivo, PEG- and RGD-modified dendrimer/siRNA nanoassemblies target tumors effectively, with PEG dissociating in acidic environments, allowing efficient gene silencing by G5PBA/siRNA polyplexes.370 Generally, the activation of functional groups on both PAMAM and the thermosome facilitates conjugation, typically using a crosslinking agent such as EDC/NHS (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide) to form stable amide bonds.371 Once the PAMAM dendrimers are conjugated to the thermosome, the positively charged surface amine groups of PAMAM can electrostatically interact with the negatively charged phosphate backbone of the siRNAs. This strong electrostatic interaction allows siRNA molecules to bind efficiently to the surface of the modified thermosome.369,368 One of the most common methods for attaching CPPs to the protein cage involves covalent bonding372 This process is typically achieved through reactive side chains on the amino acids of the protein cage. For example, lysine residues, which contain primary amine groups, can be targeted for conjugation with CPPs that have been preactivated with functional groups such as NHS esters or maleimides.373

Click chemistry is an efficient method for dendronizing β-cyclodextrin macrocycles, and the emergence of click chemistry has led to the generation of a dendritic delivery system with good yield and increased uniformity.374,375 This approach facilitates the rapid and reliable formation of covalent bonds between molecular components, resulting in the synthesis of dendritic systems with excellent yields. Moreover, click chemistry reduces the likelihood of side reactions, leading to increased uniformity of the final product.376 Copper-assisted azide‒alkyne cycloadditions (CuAAC), thiol‒ene click (TEC) reactions and Diels–Alder (DA) reactions are commonly applied to dendrimers. Luis José López-Méndez et al. introduced a novel dendritic material created by combining β-cyclodextrin (βCD) with second-generation poly(ester) dendrons.374 The dendrons were selectively attached to the seven positions on the primary face of βCD via a CuAAC click reaction. This method, along with a straightforward work-up process, enables the production of monodisperse materials with exceptionally high yields.374 Several hundred articles were surveyed and analyzed in this field. Due to the length of this review, we have not given special attention to the click chemistry applied to dendrimer synthesis.

Exosomes

Exosomes (also called extracellular vesicles) are nanosized vesicles, ranging from 30 nm to 150 nm, composed of various proteins and RNAs surrounded by a lipid bilayer membrane, similar to liposomes in structure.377 The concept of exosomes was first proposed in 1981; Trams et al. reported that exfoliated membrane vesicles with 5’-nucleotidase activity are present in the culture supernatants of some cell lines and these vesicles may have a physiological function.378 Natural exosomes are derived from the endocytosis of plasma membrane.379,380 First, invagination of the cytoplasmic membrane is processed to form the early endosomes (ESEs). Then, by exchanging materials with other organelles, the early endosomes form late endosomes (LSEs) and further sprout into multivesicular bodies (MVBs). After MVBs fusing with cell membrane, exosomes are finally bud.381 Since exosomes are derived from natural cells, they not only are highly biocompatible but also have low immunogenicity, thus realizing high transfection (in vitro) and delivery (in vivo) efficiencies without inducing serious adverse effects.382 Once considered a trivial biological phenomenon, exosomes have recently garnered much attention for use as nucleic acid delivery systems.383 Rosas, L. E. et al. added of HEK293T-derived exosomes into human monocytic cell lines, results showed that no potential cytotoxic effects were observed.384 Furthermore, a series of studies revealed that no severe immune reactions were observed in mice or humans following repeated administration of exosomes either from mice or humans.385,386,387 In addition, exosomes possess a unique homing effect in which they preferentially target the parent cell from which the exosomes are produced.388