Laser-induced coherent spin change due to spin-orbit coupling

Introduction

Laser-induced ultrafast demagnetization of ferromagnets has been a subject of extensive research over two decades1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. The majority of research in this field has focused on secondary processes, such as the thermalization of spins with phonons and magnons, which are relatively slow because they predominantly occur after the pulsed laser excitation2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. However, several types of direct light-spin interaction have also been investigated, including coherent spin excitation21,22,23, superdiffusive spin current24,25,26,27, and optically induced spin transfer28,29,30,31,32,33. These direct interactions operate at a faster timescale than secondary processes, making them instrumental for achieving an ultrafast spin manipulation.

In this work, we focus on the coherent spin excitation21,22,23 as it is regarded as a universal phenomenon present in all magnetic materials. Using a single-pulse magneto-optical Kerr and Faraday measurement, a previous experiment23 has demonstrated that the angular momentum of light undergoes a nonlinear modification when the light interacts with a ferromagnet. In accordance with this nonlinear angular momentum change of light, the authors of that work have suggested that a distinctive peak in magnetization-dependent Kerr rotation within the timescale of laser pulse is a signature of coherent spin change in the ferromagnet. The authors also have argued that the coherent spin excitation originates from relativistic quantum electrodynamics, beyond SOC effects.

On the other hand, it has been theoretically suggested that SOC itself causes an optically induced coherent spin excitation21,22, which we refer to as SOC-mediated coherent spin change. In the presence of SOC, a laser illumination can change the spin of a ferromagnet because the spin is not a good quantum number. However, this SOC-mediated coherent spin change has been largely overlooked2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. We attribute this disregard to the following two reasons. One is the ambiguity of interpreting MOKE signals in the presence of laser field and the other is a common assumption that the spin remains conserved upon optical dipole transitions. In particular, the latter common assumption has led to a widely accepted argument that there is no change in the spin moment during a laser pulse, which serves as an important initial condition of the three-temperature model1.

In this work, we revisit the fundamental question of whether a laser illumination can induce coherent spin change in a ferromagnet during a laser pulse. If the SOC-mediated coherent spin change exists, it allows for ultrafast spin manipulation because it is faster than secondary processes, thereby enhancing the operation speed of spintronic devices. Moreover, unlike superdiffusive spin current or optically induced spin transfer, this coherent spin excitation can manifest even in materials composing a single element because of the ubiquity of SOC, thereby expanding the range of materials for direct light-spin interactions.

We report that time-resolved MOKE signal exhibits a peak (or dip) during a laser pulse both in a Co/Pt bilayer, where contributions from nonlocal spin transport such as superdiffusive spin current and optically induced spin transfer potentially coexist, and in a Co single layer, where the contributions from nonlocal spin transport are absent. Consistent with previous theories21,22, our theoretical calculations based on a density functional theory and a simplified three-level system show that the spin is not conserved during optical dipole transitions because of SOC, validating that the observed MOKE peak contains a contribution from the spin change. This SOC-mediated spin change originates from anti-crossing points between two bands with different spins and different orbitals. This is a coherent process and can be distinguished from the angular momentum exchange between the spin and the orbital, which can be described as spin-orbit scatterings and thus a secondary process. Our results show that the SOC-mediated coherent spin change is a general phenomenon occurring even in single-element magnetic materials as the anti-crossing points combined with SOC are intrinsic features in all magnetic materials.

Results

Time-resolved MOKE signal of a Co/Pt bilayer

We fabricated samples of a Co (1 nm)/Pt (5 nm) bilayer or a Co (15 nm) single layer using magnetron sputtering on thermally oxidized silicon substrates. To avoid oxidation of Co, a 3-nm-thick Ta layer was additionally deposited on top of Co as a capping layer. Co/Pt exhibits a perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (Supplementary Note 1). For time-resolved MOKE measurements, we employed an 800-nm pump pulse with circular polarization and measured Kerr rotations in a polar geometry with varying the wavelength of the probe beam (see Methods). Both pump and probe pulses had a duration of approximately 150 fs. To ensure a perpendicular magnetization of the Co layer, we applied a magnetic field of 200 mT along the out-of-plane direction.

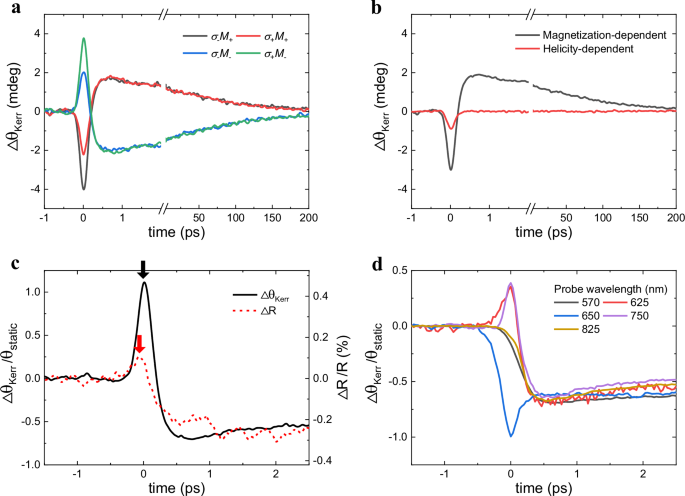

Figure 1a shows measured ultrafast Kerr rotations with the probe beam at a wavelength of 725 nm. Here, ({sigma }_{+}) (({sigma }_{-})) corresponds to right-(left)-circular polarized pump, while ({M}_{+}) (({M}_{-})) represents up (down) magnetization of Co layer. Except for the early time scale where the pump pulse is present, four signals (({sigma }_{-}{M}_{+}), ({sigma }_{+}{M}_{+}), ({sigma }_{-}{M}_{-}), and ({sigma }_{+}{M}_{-})) depends only on the magnetization direction, reflecting the laser-induced demagnetization. However, MOKE signals during a laser pulse (i.e., near time zero) show a peak or a dip, which has a strong dependence on both helicity of light and direction of magnetization. Going forward, we will refer to the transient MOKE signal, whether it manifests as a peak or a dip, simply as a ‘peak’.

a Dynamic Kerr rotation (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) induced by a circularly polarized 800-nm pump pulse (~4.5 mJ/cm2) and measured with a linearly polarized 725-nm probe pulse. b Magnetization-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) [= (({sigma }_{-}{M}_{+}+{sigma }_{+}{M}_{+}-{sigma }_{-}{M}_{-}-{sigma }_{+}{M}_{-})/4)] and helicity-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}})[= (({sigma }_{-}{M}_{+}-{sigma }_{+}{M}_{+}+{sigma }_{-}{M}_{-}-{sigma }_{+}{M}_{-})/4)] from the results of a. c Magnetization-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) normalized by static Kerr rotation ({{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}) and normalized reflectance (Delta {rm{R}}/{rm{R}}). A black (red) down arrow indicates a transient peak signal of (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}) ((Delta {rm{R}}/{rm{R}})). d Normalized magnetization-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}) measured with various probe wavelengths.

In Fig. 1b, we replot the results of Fig. 1a as the magnetization-dependent MOKE signal (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) [= (({sigma }_{-}{M}_{+}+{sigma }_{+}{M}_{+}-{sigma }_{-}{M}_{-}-{sigma }_{+}{M}_{-})/4)] and helicity-dependent one [= (({sigma }_{-}{M}_{+}-{sigma }_{+}{M}_{+}+{sigma }_{-}{M}_{-}-{sigma }_{+}{M}_{-})/4)]. The helicity-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) remains unaffected by the magnetization change in the Co layer as it does not exhibit any signature of demagnetization at later time scales. We attribute this helicity-dependent signal to the inverse Faraday effectof Pt34 (Supplementary Note 2), which arises exclusively when a laser pulse is present. On the other hand, the magnetization-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) encompasses both a faster transient MOKE peak and a slower subsequent demagnetization signal, implying a potential connection between the transient MOKE peak and the spin change in Co. We note that this transient MOKE peak is not a consequence of specular inverse Faraday effect or specular optical Kerr effect, as it occurs regardless of laser polarization (Supplementary Note 2) and there is no spectral overlap between the 800-nm pump and the 725-nm probe (Supplementary Note 3).

A laser pump primarily induces a distribution of hot electrons, which can be detected by time-resolved reflectance measurements. In Fig. 1c, we compare the magnetization-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}), normalized by a static MOKE signal ({{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}), with the normalized reflectance (Delta {rm{R}}/{rm{R}}). A clear peak of (Delta {rm{R}}/{rm{R}}) (indicated by a red arrow) is observed at time scales similar to those of the transient MOKE peak (indicated by a black arrow). This synchronicity between the two peaks suggests that the transient MOKE peak coincides with the period when the electron distribution undergoes a significant modification due to the laser pulse. We also performed time-resolved MOKE measurements with varying probe wavelengths (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Note 4) and found that the transient MOKE peak also emerges at probe wavelengths other than 725 nm, indicating that it is a general phenomenon. We note that no clear peak was observed for probe wavelengths of 570 nm and 825 nm, consistent with previous observations in Co/Pt multilayers, where ~400 nm and ~800 nm laser pulses were employed35,36,37. Highlighting the significance of multi-wavelength spectroscopy in elucidating transient spin dynamics based on our probe wavelength-dependent results, it is important to emphasize that the absence of a clear peak at 570 nm and 825 nm does not necessarily imply the absence of the transient MOKE peak; it could be obscured by a more substantial demagnetization signal.

Then, an important question is what causes this transient MOKE peak. Previous studies2,23,32 have proposed two contradicting interpretations for this transient MOKE peak. In one interpretation, the transient MOKE peak is attributed solely to an optical origin, called photo-bleaching effects, and is posited to occur without any spin change2. This interpretation may be understood as follows. MOKE signal is proportional to the anomalous Hall conductivity at the frequency of probe beam38. For metallic ferromagnets with moderate charge conductivity, the anomalous Hall effect is predominantly governed by an intrinsic Berry-phase-related mechanism39. As the Berry curvature varies with the electron occupation distribution in both magnitude and sign, it consequently influences the MOKE signal. In this respect, the laser-induced redistribution of electrons can modify the MOKE signal even without any spin change. However, this “photo-bleaching effects” interpretation must be carefully applied because it only justifies the hot-electron induced change of the MOKE signal but does not definitely prove the absence of any spin change.

The second interpretation posits that the transient MOKE peak is of magnetic origin23,32. This interpretation can be justified only when the spin change during a laser pulse is independently proved by a means other than the MOKE measurement, because the MOKE signal contains not only magnetic (spin non-conserving) but also optical (spin conserving) signals as explained in the first interpretation. Without such an independent corroboration, this second interpretation remains inconclusive, similar to the first interpretation. This ambiguity of interpreting the transient MOKE signal arises from the fact that the laser-induced MOKE signal (also x-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) signal8,40) is not directly proportional to the magnetization but includes both spin conserving and non-conserving contributions upon laser illumination. Given the experimental challenges in distinguishing between these contributions, it is of crucial importance to theoretically examine whether or not the spin changes during a laser pulse.

For this purpose, we conducted theoretical calculations for the Kerr rotation, the spin change (leftlangle delta Srightrangle), and the orbital change (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle), induced by a laser pulse (width = 150 fs, same as the experiment), using the electric dipole approximation. The ground state of Co(4 ML)/Pt(6 ML), where ML represents monolayer, was obtained through density functional theory (DFT) calculations with the openMX41. We calculated time-dependent responses by solving the quantum Liouville equation with the relaxation time approximation (Supplementary Note 5). It is worth noting that we did not employ time-dependent DFT, which could describe recently observed laser-induced changes in exchange splitting42, and did not account for phonon and magnon degrees of freedom. Consequently, our calculations do not fully capture the laser-induced ultrafast demagnetization. Nevertheless, it provides insights into how a laser pulse alters the MOKE signal, (leftlangle delta Srightrangle), and (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle) in a short time scale.

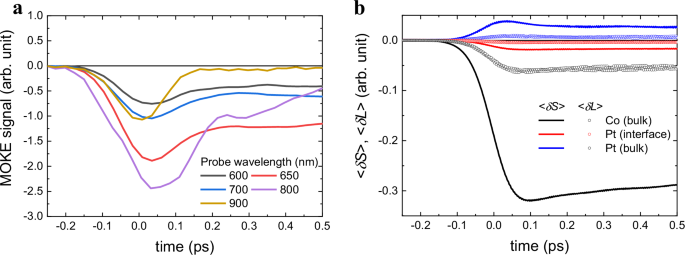

Figure 2a shows the calculated Kerr rotation for a Co/Pt bilayer with varying probe wavelengths. For the reasons mentioned above, these calculations do not quantitatively reproduce the measured ones (Fig. 1d). However, they do illustrate that the MOKE signal indeed exhibits significant variations with respect to the probe wavelength. We next check whether (langle delta Srangle) and (langle delta Lrangle) vary by a laser pulse (Fig. 2b). Due to the magnetic proximity effect, the Pt layer at the interface with Co is magnetized in equilibrium. Therefore, we display (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) and (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle) for three cases; “Co (bulk)” represents the summation over 4 ML Co; “Pt (interface)” corresponds to the value at the Pt layer in contact with Co, and “Pt (bulk)” represents the summation over the other 5 ML Pt. Three observations from Fig. 2b are worth noting. First, the sign of (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) for Pt (bulk) is opposite to that for Co (bulk). This sign difference aligns with the expectations of nonlocal spin transport such as superdiffusive spin current and optically induced spin transfer from Co layers to Pt layers. However, (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) for Pt (bulk) is significantly smaller in magnitude than that for Co (bulk), suggesting the existence of a more dominant spin non-conserving process within Co during a laser pulse, other than nonlocal spin transport. Second, (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle) exhibits a similar trend in both sign and relative magnitude to (leftlangle delta Srightrangle). However, (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle) is considerably smaller in magnitude than (leftlangle delta Srightrangle), which is consistent with previous XMCD measurements10,11. This result rules out the possibility of orbital-to-spin conversion due to spin-orbit scatterings being a dominant process. Third, (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) and (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle) for Pt (interface) follows the same trend as those for Co (bulk), indicating that this interfacial layer behaves as another magnetic layer. All these observations collectively suggest the presence of a dominant spin change process during a laser pulse, distinct from nonlocal spin transport and secondary spin-orbit scatterings. The remaining process that can account for these findings is the coherent and direct light-spin interaction for states where spin up and down components are superposed due to SOC, which we will discuss later.

a Magnetization-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) calculated with various probe wavelengths. b Time evolution of nonequilibrium spin densities (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) (lines) and orbital densities (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle) (symbols) of Co (bulk), Pt (interface), and Pt (bulk). We used the laser fluence of 3.3 mJ cm−2.

Time-resolved MOKE signal of a Co single bilayer

MOKE signals of a Co/Pt bilayer have contributions from superdiffusive spin current and optically induced spin transfer, making it challenging to clearly identify the presence of SOC-mediated coherent and direct light-spin interaction. To avoid this complexity, we investigated a Co single layer, which does not contain any contributions from the nonlocal spin transport. We fabricated a 15-nm thick Co single layer on a SiO2/Si substrate and carried out the same measurements done for a Co/Pt bilayer.

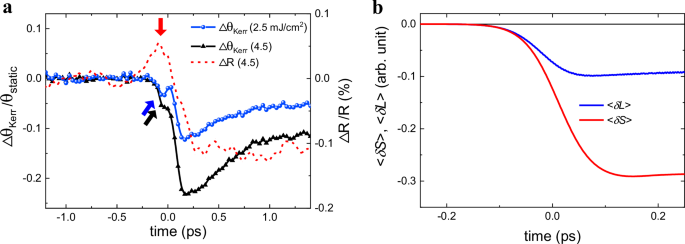

According to our theory, the single Co layer should also exhibit transient spin change caused by direct light-spin interaction mediated by SOC. Figure 3a presents the normalized magnetization-dependent (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}) and the normalized reflectance (Delta {rm{R}}/{rm{R}}) of a Co single layer, measured with the 725-nm probe pulse. Similar to Co/Pt, we observe a clear (Delta {rm{R}}) peak (indicated by a red arrow) and a subdued (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) peak (indicated by blue and black arrows for different laser fluences) during a laser pulse. Importantly, this observation highlights the universal presence of coherent spin change during laser excitation. We attribute the smaller (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}) peak of Co compared to that of Co/Pt to the following two reasons. First, the effective SOC of Co is smaller than that of Co/Pt. Second, the absence of both superdiffusive spin current and optically induced spin transfer in a Co single layer, which may contribute to the transient MOKE peak to some extent in Co/Pt, plays a role in this difference. Similar to Co/Pt, a transient MOKE signal of Co also emerges at probe wavelengths other than 725 nm, although the signal is weaker due to the reasons discussed in Supplementary Note 4.

a Normalized magnetization-dependent Kerr rotation (/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}) and normalized reflectance (/{rm{R}}). Blue circle (black triangle) symbols are (/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}) obtained with laser fluence of 2.5 mJ cm−2 (4.5 mJ cm−2). Red dotted curve is (Delta {rm{R}}/{rm{R}}). A blue (black) arrow indicates a transient peak signal of (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}). A red arrow indicates a transient peak signal of (Delta {rm{R}}/{rm{R}}). b Calculated time evolution of (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) and (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle) for a Co single layer (10 ML).

Figure 3d shows the time evolution of the calculated (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) and (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle) for a Co single layer (10 ML). It is evident that (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) emerges even without nonlocal spin transport. Moreover, the change of (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) is larger than that of (leftlangle delta Lrightrangle), ruling out orbital-to-spin conversion due to spin-orbit scatterings as a dominant process. This result provides compelling evidence that optical dipole transitions indeed induce the spin change of a single Co system. We further justify this argument by presenting a simplified three-level system below.

Coherent optical dipole transition with spin change: model study of a three-level system

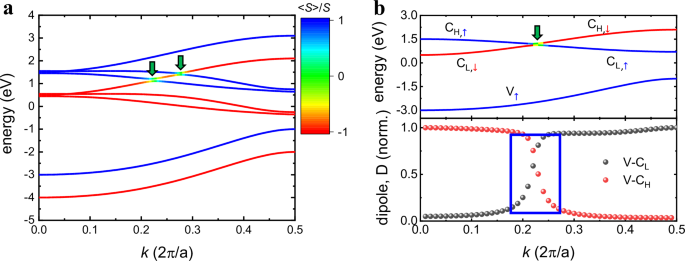

We have considered a sp3 tight-binding model for a ferromagnet with SOC in a simple cubic structure (Methods). Figure 4a shows the energy dispersion where the color indicates the normalized (leftlangle Srightrangle). Two anti-crossing points, where the spin states are mixed due to SOC, are denoted by green down arrows. From the dispersion of Fig. 4a, we select three bands that have a single anti-crossing point (top panel of Fig. 4b). These three bands are as follows: ({{rm{V}}}_{uparrow }), representing the occupied valence band with spin up; ({{rm{C}}}_{{rm{L}},uparrow (downarrow )}), representing the unoccupied conduction band with intermediate energy and spin up (down); and ({{rm{C}}}_{{rm{H}},uparrow (downarrow )}), the unoccupied conduction band with highest energy and spin up (down). We calculate the dipole (D= langle nu vert {hat{d}} vert {c} rangle) where (|vrangle) and (|crangle) are the eigenstates of the valence and conduction bands, respectively, and (hat{d}) is the dipole operator. The value of (D) quantifies the optical dipole transition between ({{rm{V}}}_{uparrow }) and a conduction band (bottom panel of Fig. 4b).

a Energy dispersion of sp3 tight-binding model for a magnetic material. The color represents the normalized (leftlangle Srightrangle); blue (red) for spin majority (minority) states. Green down arrows represent anti-crossing points. b (top panel) Dispersion of a three-level system, which is taken from a and contains a single anti-crossing point (green down arrow). ({{rm{V}}}_{uparrow }) is the occupied valence band with spin up. ({{rm{C}}}_{{rm{L}},uparrow (downarrow )}) is the unoccupied conduction band with intermediate energy with spin up (down). ({{rm{C}}}_{{rm{H}},uparrow (downarrow )}) is the unoccupied conduction band with highest energy and spin up (down). (bottom panel) V-CL (V-CH) is the normalized strength of optical dipole transition between V and CL (CH).

For k values away from the anti-crossing point, the normalized (D) is close to zero for spin non-conserving transitions (i.e., transitions between ({{rm{V}}}_{uparrow }) and ({{rm{C}}}_{{rm{H}}({rm{L}}),downarrow })), whereas it is close to one for spin conserving transitions (i.e., transitions between ({{rm{V}}}_{uparrow }) and ({{rm{C}}}_{{rm{H}}({rm{L}}),uparrow })). This observation aligns with the common assumption that optical dipole transitions conserve spin. However, this assumption breaks down for k values near the anti-crossing point (indicated by a box). In this regime, (D) exhibits finite values due to SOC-induced spin mixing. Therefore, optical dipole transitions near the anti-crossing point do not conserve spin. This transition is not a result of spin-orbit scattering but rather a coherent process, consistent with a previous theory with a two-level system22. It is noteworthy that this anti-crossing physics combined with intraband scatterings may induce a sharp spin moment reduction43. It is also noted that there is an interesting similarity between the highly nonlinear process induced by intensive light, studied in this work, and a linear response induced by an electric field such as the spin Hall effect44 and the magnetic spin Hall effect45,46 in 3d transition-metal ferromagnets. In both cases, anti-crossing points between bands with different orbitals and different spins play a crucial role. This conclusion is further supported by our calculations, which show that the non-equilibrium spin density (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) vanishes in the absence of SOC and is approximately linear in SOC (Supplementary Note 6). Moreover, our calculations reveal that (leftlangle delta Srightrangle) is significantly larger in a thin film compared to the bulk (Supplementary Note 7). This enhancement can be attributed to the increase in the number of anti-crossing points in the thin film due to surface effects.

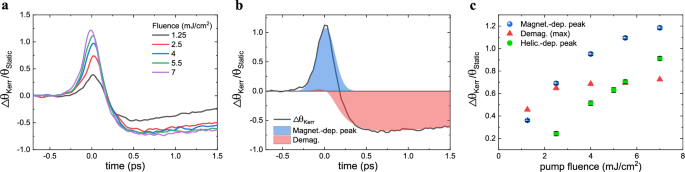

When this coherent optical transition with spin change is non-negligible, it would exhibit a correlation with the amount of demagnetization. Therefore, we compare the transient MOKE peak, which contains a contribution from this coherent transition, and the demagnetization in experiments. For this purpose, we examine the fluence dependence of time-resolved MOKE signals for a Co/Pt bilayer, as it exhibits a more pronounced transient peak (Fig. 5a). In Fig. 5b, the normalized magnetization-dependent Kerr rotation (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}) is fitted with the function7:

Here, σ represents the duration of the transient MOKE peak, and “erfc” denotes the complementary error function. The equation encompasses transient peak, subsequent demagnetization, and relaxation processes. While we retained σ as a fitting parameter, its dependence on pump fluence is negligible, and it aligns with the duration of the laser pulses used (as detailed in Supplementary Note 8).

a Fluence dependence of magnetization-dependent Kerr rotation (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}). b Graph fitting results for (Delta {{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Kerr}}}/{{rm{theta }}}_{{rm{Static}}}). c Fluence dependence of transient magnetization-dependent peak (blue), demagnetization signal (red), and helicity-dependent peak (green), obtained from graph fitting.

Our analysis reveals that both the transient magnetization-dependent peak ({A}_{{peak}}) and demagnetization ({A}_{{demag}}) exhibit a similar fluence dependence and saturate with increasing fluence, while the helicity-dependent peak continues to linearly increase (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Note 2). This similar fluence dependence between the transient magnetization-dependent peak and demagnetization indicates that both signals originate from the same spin bath. Careful interpretation of transient signals in laser-induced magnetization dynamics is essential2,47,48. Considering the response of MOKE signal to initial magnetization and pump fluence, as well as its consistent appearance across different sample geometries and probe wavelengths, we suugest that the transient MOKE signal observed originates from spin anti-crossing points due to spin-orbit coupling. This phenomenon is distinct from the nonlocal spin transfer or the nonmagnetic optical Kerr effect. Fig. 6

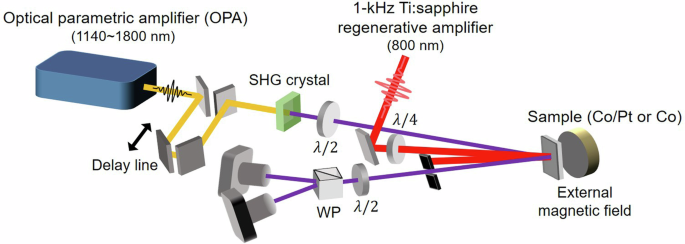

({rm{lambda }}/2): half-wave plate, ({rm{lambda }}/4): quarter-wave plate and WP: Wollaston prism.

Discussion

By combining magneto-optical spectroscopy and theoretical calculations, we have investigated the SOC-mediated coherent spin change in both a Co/Pt bilayer and a single Co layer. Our results suggest that a transient MOKE peak must be partially related to the SOC-mediated coherent spin change, as supported by our theoretical calculations. We note that our calculations do not include contributions from nonlinear relativistic quantum electrodynamics, which was proposed as an origin of coherent spin change during laser illumination23. Our results demonstrate that laser-induced coherent spin change arises due to SOC, even in the absence of nonlinear relativistic quantum electrodynamics. Moreover, we show that the SOC-mediated coherent spin change exists for a single Co layer, where the contributions of superdiffusive spin current and optically induced spin transfer are absent. This universal presence of direct interaction between light and spin, as well as its potential role in the demagnetization, emphasizes the significance of this phenomenon. It also suggests that the widely used three-temperature model1, which assumes no spin change during a laser pulse, needs to be modified. Several studies have considered the initial hot electron distribution (nonthermal electrons) in the three-temperature model49,50,51, but have still assumed no spin change. Additionally, the spectroscopic explanation of the role of electronic structure in spin dynamics provides the foundation for future research to construct and accomplish more efficient direct light-spin interaction by exploiting the anti-crossing physics.

Methods

Set-up for time-resolved spin dynamics measurement

We used 800-nm pump pulses from a 1-kHz Ti:sapphire regenerative amplifier to excite the magnetic samples. Optical probe pulses at different wavelengths (570–900 nm) were generated by frequency doubling the infrared pulses from an optical parametric amplifier, which is pumped by the same regenerative amplifier. Both pump and probe pulses had a pulse duration of approximately 150 fs, facilitating time-resolved measurements of spin dynamics by adjusting time delay between the two pulses. The pump beam having a diameter of approximately 200 μm was focused on the sample, while the probe beam was slightly smaller compared to the pump beam. To prevent undesired optical effects, the probe pulses were slightly tilted from the pump pulses. The incidence angle was kept at <5 degrees. This configuration ensures polar Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect (MOKE) measurements in a reflection geometry to study spin changes. An external magnetic field of 200 mT was applied to saturate the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy of Co/Pt and induce a net out-of-plane magnetization in Co.

({boldsymbol{s}}{{boldsymbol{p}}}^{{boldsymbol{3}}}) tight-binding model

We consider a ferromagnetic system with SOC in a simple cubic structure. Assuming (s{p}^{3}) orbitals, we model the Hamiltonian as,

Here, ({{mathscr{H}}}_{L}) is the orbital part of Hamiltonian, ({J}_{{ex}}) is the exchange interaction, (lambda) is SOC, and ({bf{m}}) and ({bf{S}}) correspond to the unit vector along the magnetization and the spin angular momentum operator ((hslash /2){boldsymbol{sigma }}), respectively. The orbital angular momentum operator ({bf{L}}) is expressed with (s{p}^{3}) basis, giving ({{mathscr{H}}}_{L}) as

For instance, ({E}_{{ss}}left({bf{k}}right)), ({E}_{{xx}}left({bf{k}}right)), and ({E}_{{sx}}left({bf{k}}right)) are given by

Other terms are defined in a similar way. We use ({E}_{s}=-2.0), ({E}_{p}=1.0), ({t}_{ssigma }=-0.25), ({t}_{psigma }=0.4), ({t}_{ppi }=-0.2), and ({gamma }_{{sp}}=0.4).

Responses