Late eating is associated with poor glucose tolerance, independent of body weight, fat mass, energy intake and diet composition in prediabetes or early onset type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Dietary interventions are the cornerstone of the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D). Total energy intake and meal composition are determinants of daily glucose excursions. Meal timing may also be important due to diurnal variation of glucose tolerance [1]. Previous studies consistently demonstrated that late eating is linked to poorer glucose metabolism, in association with higher BMI, increased body fat, as a result of greater energy intake [2] and highly processed food consumption [3]. The distribution of energy intake later in the day may also prolong overnight postprandial glucose excursions and result in circadian misalignment both contributing to impaired glucose metabolism [2].

Our goal was to test the hypothesis that the associations of habitual later mealtime and worse glucose metabolism are independent of body weight, fat mass, daily energy intake, or diet composition in adults with overweight and obesity and diet or metformin-controlled prediabetes or T2D.

Methods

A total of 26 adults (50–75 years old) with overweight or obesity, diet or metformin-controlled prediabetes or T2D, HbA1c of 5.7–7.5%, a ≥ 14-h eating window, ≥6 h of sleep, stable weight, and no history of bariatric surgery, were enrolled at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (New York City). Data were collected during a 14-day free-living assessment from the NY-TREAT parent trial (June 2021–December 2022) [4].

Food intake and meal timing were assessed using five Automated Self-Administered 24-h (ASA24®) recalls, and mealtimes validated by time-stamped photos taken in real-time with the myCircadianClock app.

Participants were categorized into Later Eaters (LE) if ≥45% daily calories were consumed after 5 pm or Early Eaters (EE).

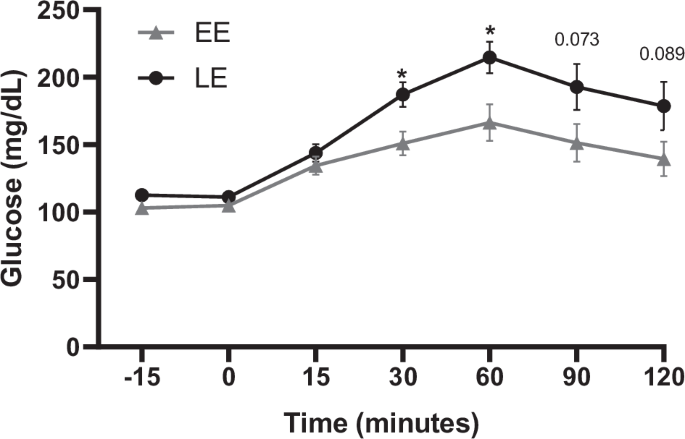

Measurements included triplicate assessments of blood pressure, body weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, and fat mass. A 75 g 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was conducted after a 10-h fast, with biomarkers analyzed at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean (SD) and figures as mean (SEM). Group comparisons used Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Chi-square test. Linear mixed models with OGTT-derived glucose variables as outcome, were performed with group (EE or LE) and time as fixed effects, with and after excluding patients with T2D. General linear models assessed glucose with groups as fixed factors, and diabetes status, body weight, fat mass, dietary intake and composition as covariates. Significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses used IBM SPSS Statistics software version 29.0.0.0. Please see Supplementary Methods file for details.

Results

Twenty-six participants, 17 women, 3 with T2D and 4 on metformin, aged 60 (7) years, systolic blood pressure 121.9 (12.6) mmHg, diastolic blood pressure 78.5 (10.2) mmHg, waist circumference 107.5 (14.3) cm, weight 90.9 (20.2) kg, BMI 32.5 (5.3) kg/m2, fat mass 37.4 (12.1) kg, fat-free mass 53.5 (14.5) kg, were studied.

EE (n = 13) and LE (n = 13) did not differ in age, sex, anthropometrics, and body composition. Participants with T2D (n = 3) were all in the LE group (Supplementary Table 1).

Total daily energy intake and macronutrients composition did not differ between groups (Supplementary Table 2). Compared to EE, LE consumed almost twice as many calories after 5 pm, with higher amounts of fat and carbohydrates consumption, and a trend toward higher protein and sugar consumption (Supplementary Table 3).

Fasting glucose, insulin, and C-peptide did not differ between groups (Table 1). Glucose concentrations increased more over time after an oral glucose load in LE, compared to EE (p = 0.010). LE had greater mean glucose during OGTT, greater total glucose area under the curve (tAUC), with greater glucose concentrations at time 30 and 60 min (Table 1) (Fig. 1) (Supplementary Table 4). Analysis excluding participants with diabetes showed similar results: the OGTT glucose concentrations increased more in LE (n = 10) compared to EE (n = 13) (p = 0.031), with greater concentrations at 30 and 60 min (Supplementary Table 5). The significant difference in glucose outcomes between LE and EE persisted after adjusting either separately for body weight, fat mass, energy intake and diet composition or for all covariates combined (p < 0.005) (Supplementary Table 6). When adjustment was made with combined covariates including diabetes status, only a trend for differences in glucose at 30 and 60 min persisted (p = 0.082 and p = 0.074, respectively) (Supplementary Table 7).

Mean and SEM. P-value: * <0.05, **<0.01, if a value does not appear, it is because is ≥1 and is not considered a trend or statistical significance. EE Early Eaters, LE Later Eaters.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that greater energy intake after 5 pm is associated with poorer glucose tolerance in adults with obesity and diet or metformin-controlled prediabetes or T2D, independently of higher body weight or fat mass, diet composition or greater energy intake.

Our data confirm the association of late eating with worse glucose tolerance shown in previous studies in individuals without obesity [1]. Adding to previous findings on the detrimental effect of late eating on BMI and metabolism [2] and its association with poorer diet [2, 3], we now observed that the association of LE with poorer glucose tolerance is independent of greater body weight, fat mass, calorie amount, or poorer diet composition.

In previous studies associating eating late with poorer glucose metabolism, later eaters had higher BMI, higher body fat [5, 6], as well as lower satiety and greater hunger [7, 8] which may have explained their greater daily calorie intake. Food consumed in the evening, compared to morning, is typically higher in energy density resulting in an overall higher total energy intake [2], which may explain why late eating is associated with greater body weight and fat mass. Therefore, the glucose benefits observed when energy intake is distributed earlier in the day may be explained by a lower body weight. However, even in individuals reporting to consume the same total daily calorie amount, late eaters can present higher BMI/fat mass and poorer glucose metabolism, highlighting the potential role of meal timing per se, independently of calorie amount, on poorer metabolism [9,10,11,12].

Our study shows that older individuals with prediabetes or early T2D who are habitual later eaters have poorer glucose tolerance, independently of body weight or fat mass and energy intake. This is in agreement with short-term intervention trials (1–14 days) in healthy volunteer. Participants consuming an isocaloric diet aiming at weight stability showed worse glucose tolerance and lower resting-energy expenditure when calories were consumed later in the day [13, 14]. This may be related to previously reported higher postprandial glucose response after dinner compared to breakfast [14,15,16]. The importance of late eating on glucose was also shown in a prospective observational epidemiological study of 2642 women at risk of T2D: eating after 9 pm was associated with 1.5 times higher 5-year risk of developing T2D [17].

A combined intervention of caloric restriction with AM versus PM distribution of daily calories glucose and HbA1C decreased more, and insulin response was higher when calories were consumed in the morning compared to the evening [18, 19], highlighting the importance of meal timing on glucose metabolism in individuals with T2D. However, another weight loss study in 23 individuals with obesity and prediabetes or T2D, showed no differences in weight or metabolism when 50% of the total daily calories were consumed in the morning versus the evening [20].

Diet composition is also a well-established determinant of T2D risk. Observational studies have shown that late eaters tend to select highly processed high-carbohydrates and/or fats meals in the evening [2, 3]. Our study supports those findings. LE consumed more carbohydrates and fats after 5 pm compared to EE. This behavior has previously been associated with worse overnight glucose metabolism and may result in desynchronization of the peripheral circadian system [2] that can lead to even worse glucose tolerance.

Bias and limitations include the inclusion criteria of the NY-TREAT study [4], focusing on individuals with a prolonged ≥14-h eating window, introduces a potential bias. However, given the prevalence of such eating patterns in the general population, the data may still be representative. Despite real-time data collection via a smartphone app, there remains an element of self-reporting as participants need to remember to photograph their meals, though validations suggest a minimal 10% error rate [3]. The study’s small sample size is a limitation but, for pilot studies such as this one, former power calculation is not always possible. However, caution is advised in generalizing findings, as the cohort specifically targets individuals with prediabetes or T2D and obesity. Replicating the study in more diverse populations and age groups would enhance external validity, contributing to a broader understanding of the results’ applicability beyond the studied demographic.

Conclusion

This exploratory study aligns with previous literature showing that late consumption of calories is associated with worse glucose tolerance. Late eating is associated with greater consumption of calories mostly from carbohydrates and fats and may lead to prolonged evening postprandial glucose excursions contributing to worse glucose tolerance. Our findings, that late eating is associated with poorer glucose metabolism, is neither explained by a higher BMI or body fat, nor by larger amount and worse daily diet composition, will need confirmation in future studies. Further research is warranted to explore the effect of both the composition and the timing of the last eating occasion on overnight glucose and glucose tolerance.

Research in context

-

What is already known about this subject?

Eating late has been associated with increased fatness and poorer glucose metabolism, in part due to eating unhealthy and calorie-dense food later in the day.

-

What is the key question?

Does eating late contribute to poor glucose tolerance without depending on increased body weight, fat mass, daily energy intake or diet composition?

-

What are the new findings?

Later eaters exhibit poorer glucose tolerance compared to earlier eaters. This was independent of body weight, fat mass, calories and diet composition and highlights the novelty of our findings.

-

How might this impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Late eating independently contributes to poorer glucose tolerance. Addressing meal timing may have implications for managing glycemic control in diet or metformin-controlled prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

Responses