Legacy effects of crop diversity on weed-crop competition in maize production

Introduction

Weeds are a major constraint to crop yields1,2 and are often managed with herbicides. The ubiquitous use of herbicides has resulted in water body pollution3, biodiversity reduction4,5, and human health concerns6,7,8. Reliance on herbicides has also contributed to the rise of herbicide-resistant weeds9, threatening future crop productivity. Consequently, weed management strategies that reduce the impact of crop production on the environment while suppressing weeds are an important means of increasing agricultural sustainability.

Intercropping is a management practice where multiple crop species or cultivars are planted in the same place and time. Farmers can use this practice to suppress weeds by reducing weed access to resources like soil nutrients, light, and water. Although it is unrealistic to expect intercrops to always suppress more weeds than monocultures, these systems often have lower weed biomass than the monocultures of the less competitive species in the intercrop10,11. For instance, in a review of 58 cereal-legume intercropping studies, weed biomass in cereal-legume intercrops was lower than in legume monocultures12. In these studies, weed suppression was likely supported by the reduced soil mineral nitrogen observed in the intercrops compared to the legume monocultures. The more complete use of resources in intercrops stems from the diversification of crop traits13.

The resource pool diversity hypothesis describes how agricultural diversification affects weed-crop competition through changes in soil resources14. It predicts that diverse cropping systems provide a greater range of inputs to the soil resource pool, increasing the number of soil niches from which plants may acquire resources and reducing weed-crop competition. In intercropped systems, the use of multiple crop species can increase the diversity of soil resources because plants have species-specific effects on soil characteristics like nutrient availability12,15,16,17, microbial communities18,19,20,21, and soil structure21,22. Past experiments already provide initial support to the resource pool diversity hypothesis, showing that crops are more tolerant to weed competition in intercrops compared to monocultures22,23. However, it is possible that diverse systems, like intercrops, lessen future weed-crop competition. Given that the legacy effects of crops on weed-crop competition can persist after tillage17, intercropping may be a promising way to affect weed-crop competition. Understanding how intercropping affects weed-crop competition in future crops will help farmers design systems that are less vulnerable to weeds.

Maize tissue nutrient composition, weed community structure, and weed-crop competition were evaluated to assess the legacy effects of intercrop diversity in organically managed annual and perennial cropping systems. The experiment driving this analysis consisted of two phases: a conditioning phase during which crop diversity treatments were established and maintained for three years in annual and perennial cropping systems and a subsequent uniformity phase in which maize was grown on the soils of the previous crop diversity treatments. Here, we focused on the uniformity phase, hypothesizing that soils conditioned with high crop diversity will have reduced weed-crop competition compared with soils conditioned with low crop diversity. Building on the resource pool diversity hypothesis, we expected weed-crop competition to differ because soils conditioned with greater crop diversity would have more soil niches. The change in soil resources across the crop diversity gradient could be reflected in maize tissue nutrients and weed communities. Furthermore, we expected that although crop diversity legacy would have similar effects within the annual and perennial cropping systems, there would be differences in crop tissue nutrients, weed communities, and weed-crop competition intensity between the two cropping systems.

Methods

Conditioning phase

From the summer of 2016 to the spring of 2019, four levels of crop diversity were established and maintained in annual and perennial cropping systems. All crops in the conditioning phase were managed using USDA-certified organic practices24. The experiment was conducted in central New York, USA (NY; 42°44’10.1” N 76°39’09.8” W) on a Honeoye (fine-loamy, mixed, semiactive, mesic Glossic Hapludalfs) and Lima (fine-loamy, mixed, semiactive, mesic Oxyaquic Hapludalfs) silt loam and in northern Vermont, USA (VT; 45°00’28.1” N 73°18’28.4” W) on a Benson (Loamy-skeletal, mixed, active, mesic Lithic Eutrudepts) silt loam25. Before the conditioning phase, the NY soils had a pH = 7.6 and 3% organic matter, and the VT soils had a pH = 6.6 and 5% organic matter between a depth of 0 to 20 cm. The NY site was in the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) plant hardiness zone 5b, and the VT site was in zone 4a26.

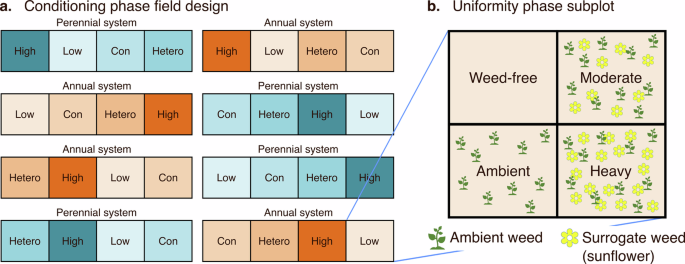

The conditioning phase was set up as a split-plot randomized complete block design with a two-level cropping system treatment (annual and perennial) as the main plot and a four-level crop diversity treatment as the subplot (Fig. 1). The four crop diversity levels were low (one species, one cultivar), conspecific (one species, four cultivars), heterospecific (four species, one cultivar per species), and high (four species, four cultivars per species) (Table 1). The annual system included both a summer and winter phase. All treatments were replicated in four blocks at each site.

The conditioning phase was composed of four diversity treatments (subplots) nested within annual or perennial cropping system treatments (plots) for three years (a). All treatments were replicated in four blocks. Afterward, a uniform stand of maize was planted in 2019, where weed-crop competition was evaluated (b). Each conditioning phase subplot was split into quadrants, and maize was subjected to differing weed seeding rates in each quadrant. In the figure, ‘Con’ and ‘Hetero’ denote the conspecific and heterospecific diversity treatments.

Throughout the conditioning phase, the seeding rates of the intercropped treatments (conspecific, heterospecific, and high diversity) were based on a replacement design of the low diversity treatment. Fertilization and tillage regimes were consistent within the annual and perennial systems but varied between systems, sites, and years (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). In both systems, fertilization rates were based on the low diversity crop needs defined by yearly soil tests. Fertilization was accomplished with poultry manure (Kreher’s; Clarence, NY, USA), dairy manure (Aurora Ridge Dairy, Aurora, NY, USA), and potassium sulfate (North Country Organics; Bradford, VT, USA and Bourdeau Bros., Inc; Champlain, NY, USA). For more details on the management of the conditioning phase, refer to Bybee-Finley et al.27.

Biomass of the conditioning phase crops was sampled based on the maturity of the low-diversity crop. At sampling, two 0.25 m2 quadrats were randomly placed within each diversity treatment subplot (n = 32 per site; Fig. 1a); crop biomass was clipped at ground level, sorted by species, dried at 60 °C for at least one week, and weighed. To minimize sampling error, crop cultivars were not separated. Similarly, sorghum sudangrass (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench × Sorghum sudanese Piper) and sudangrass (Sorghum sudanense (Piper) Stapf, var. Piper), triticale (×Triticosecale Wittm. ex A.Camus) and cereal rye (Secale cereale L.), and timothy (Phleum pratense L.) and orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.) were not separated at the species level to reduce sampling error.

Crop biomass data from the final forage harvests of the conditioning phase describe how conditioning phase crops may have impacted weed and crop growth during the uniformity phase. Data were used from the last summer annual cut in 2018, which was August 21 in NY and August 20 in VT; the following winter annual cut from 2019, May 16 in NY and May 28 in VT; and the last perennial cut in 2019 on May 23 in NY and June 3 in VT. For a description of forage yields, weed biomass, forage nutrient value, and yield stability across the entire conditioning phase, see Bybee-Finley et al.27.

Uniformity phase

After the final harvest of the conditioning phase, the entire experiment was moldboard plowed to a depth of 15 cm on May 24, 2019, in NY and June 5, 2019, in VT. A seedbed was prepared by tandem disking and roller harrowing on May 26, 2019, in NY and June 5, 2019, in VT. The subplot boundaries of the conditioning phase diversity treatments were geolocated, and each diversity treatment subplot was divided into quadrants (6.9 by 4.6 m in NY and 5.3 by 3.0 m in VT; Fig. 1b). Each quadrant was assigned one of the following weed treatments: (1) weed-free, (2) ambient-weed, (3) moderate-weed, or (4) heavy-weed to create a weed-crop competition gradient. The moderate- and heavy-weed treatments were established by broadcasting 34,790 and 69,580 seed ha−1 of organic cv. ‘Daytona sunflower 75 M’ (surrogate weed) on May 28, 2019, in NY and June 7, 2019, in VT. Organic cv ‘Viking 0.45-88 P’ maize (crop plant) was planted 4.5 cm deep with 76 cm row spacing at 88,920 seeds ha−1 immediately after surrogate weed seeding across the entire experiment. Sunflower and maize were chosen for the uniformity phase of the experiment because they were not grown during the conditioning phase and would not have species-specific pathogen or resource-use legacies. Furthermore, the similarity between maize and sunflower in terms of growth rate, habit, stature, and phenology would maximize competition between the two species. Treatments in the uniformity phase were not fertilized to maintain any potential legacy effects of the conditioning phase on soil nutrient availability.

The weed-free treatment was created by manually removing weed seedlings throughout the growing season. Conversely, the ambient-weed treatment was not weeded to represent the soil weed seed bank. Likewise, weeds that emerged in the moderate- and heavy-weed treatments were not controlled. As such, the moderate- and heavy-weed treatments reflect the competition that the sunflower imposed on the maize in addition to ambient weeds (Fig. 1b).

Maize leaves were sampled for tissue nutrient content in the weed-free and ambient-weed treatments (n = 64 per site) to assess crop nutrient uptake. At both sites, sampling occurred no more than three days after maize began tasseling: July 31, 2019, in NY and August 2, 2019, in VT. Five maize plants were randomly selected within each weed-free and ambient-weed treatment. If a selected plant was tasseling, the leaf at the maize ear node, excluding its leaf collar, was sampled. Conversely, if the selected plant had not tasseled, the entire first fully developed leaf below the whorl was sampled to account for potential differences in tissue nutrients28,29. Samples were dried at 55 °C for one week and sent to Dairy One (Ithaca, NY, USA) for tissue nutrient testing.

The tissue analysis protocol is described in the protocols of Dairy One30. Briefly, samples were sequentially exposed to 8 ml nitric acid (HNO3), 2 ml hydrochloric acid (HCl), and 1 ml of 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Then, they were digested with a CEM Microwave Accelerated Reaction System MARS6 (CEM; Matthews, NC, USA) with MarsXpress Temperature Control using 50 ml calibrated Xpress Teflon PFA vessels with insulating sleeves made of kevlar and fiberglass. Digested samples were analyzed with a Thermo iCAP 6300 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) for calcium, phosphorous, magnesium, potassium, iron, zinc, copper, manganese, and boron. Tissue nitrogen was calculated from 1 mm of sample matter, combusted with a CHN628 Carbon Nitrogen Determinator (Leco; St Joseph, MI, USA).

Ambient-weed communities were sampled during peak summer annual weed biomass on August 19, 2019, in NY and August 15, 2019, in VT. One randomly placed (76 cm by 64 cm) 0.50 m2 quadrat was sampled in each ambient-weed treatment (n = 32 per site). The 76 cm edge of the quadrat was centered over one maize row to ensure an equal proportion of inter- and intra-row area in each sample. All weeds above 5 cm tall or 5 cm wide were clipped at the soil surface and identified at the species level. The sampled plant material was dried at 55 °C for one week and weighed. Only data from the ambient-weed treatment were used for the weed community analyses because the other weed treatments artificially influenced weed communities through weed removal or surrogate weed seeding.

Maize was harvested as silage at 65 to 68% moisture from September 12 to 13, 2019, in NY and October 3, 2019, in VT. All maize and weeds over 5 cm tall or 5 cm wide were sampled in two randomly placed (76 cm by 64 cm) 0.50 m2 quadrats at the weed-treatment level (n = 128 per site). In the ambient-weed treatments, where weed communities were sampled, both quadrats were randomly placed in an area unaffected by previous sampling. The 76 cm edge of the quadrat was centered over one maize row to ensure an equal proportion of inter- and intra-row area in each sample.

The total maize fresh biomass was calculated immediately after sampling. Afterward, maize samples were chipped with a LSC 1100 chipper shredder at the NY site (MacKissic; Parker Ford, PA, USA) and a CS 4325 chipper shredder (Troy-bilt; Valley City, Ohio, USA) at the VT site. Immediately after chipping, a 500 to 800 g fresh subsample was weighed in the field. The dry biomass of the subsample was calculated after oven-drying at 55 °C for at least two weeks. Total maize sample dry biomass was calculated as the product of the dry subsample biomass to fresh subsample biomass ratio and fresh total biomass. Total weed biomass was determined after oven-drying at 55 °C for at least two weeks. Total dry maize and weed biomass data were used to analyze weed-crop competition.

Statistical analysis

The crop biomass at the end of the conditioning phase describes how well the diversity gradients were established, and it was assessed using linear mixed-effects models. In all models, diversity treatment was a fixed effect, and field block was a random effect. Data from the winter annual, summer annual, and perennial forage harvests were analyzed separately to avoid imbalance at the cropping systems level. Furthermore, the two sites were modeled separately to get the model residual error to be normally distributed. Throughout this analysis, data normality was assessed using Q-Q plots, variance was tested using Levene’s test, and model fit was evaluated through residual plots. FisherLSD tests were used to compare the estimated marginal means of the diversity treatments within each site and cropping system.

To assess if soil conditioned with varying crop diversity influenced the nutrient content of maize tissues in the uniformity phase, a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) test was applied to analyze tissue nutrient data. The PERMANOVA used Euclidian distance and sequentially tested the effect of site, system, diversity, weed treatments, and all interactions of these variables on maize tissue nutrients. Before testing, the maize tissue data were centered by subtracting the means of tissue variables and scaled by dividing each tissue variable by its standard deviation.

The leaf tissue data were visualized through principal component analysis (PCA) plots. Applying a PCA to the tissue data was appropriate because the data had been relativized, had low skewness, and the underlying relationships between tissue nutrients were linear. The PCAs were analyzed by overlaying the site, system, weed treatments, and the vectorized contribution of each tissue nutrient to the ordination spread.

Univariate linear mixed-effects models of each tissue nutrient complemented the multivariate analysis of maize tissues. All models investigate tissue nutrients by considering site, system, diversity treatment, weed treatment, and all interactions between these variables as fixed effects. The univariate maize tissue models included experimental block, plot, and subplot as hierarchically nested random effects (Fig. 1). The fit of these models was confirmed with residual plots. Values for zinc, copper, manganese, calcium, and nitrogen were log-transformed to improve data normality. Estimated marginal means were compared to illustrate differences between treatments.

To determine the effects of site, system, and diversity treatment on uniformity phase weed community structure, species-level weed biomass data was assessed with a PERMANOVA using Bray-Curtis distance. Bray-Curtis distance was used because it accurately represents plant community biomass data compared with other distance measurements31.

To describe weed-crop competition in the uniformity phase, maize and weed biomass data were analyzed using the rectangular hyperbolic yield function proposed by Spitters32:

In this function, crop yield (Yc; g m−2) is the quotient of inverse crop yield potential (a0; m2 g−1)−1 per unit of crop density (Nc; plants m−2) and the yield-reducing effect of weeds (iw; plants g−1) per unit of weed density (Nw; plants m−2). The a0 parameter describes how much land area is required for each gram of crop yield. Thus, smaller a0 parameters denote greater yield potential. The iw parameter affects the slope of the hyperbola and describes weed-crop competition intensity; the higher the iw value, the more intensely weeds compete with crops. Following Ryan et al.33 and Menalled et al.21, weed biomass (g m−2) was used instead of weed density (plants m−2) for Nw to model weed abundance.

The competition function (Eq. 1) was used to model crop and weed biomass for each site separately. The models comparing weed-crop competition across diversity treatments were fit separately for annual and perennial cropping systems and had a random effects structure that accounted for variability across experimental blocks and subplots (Fig. 1). The models comparing weed-crop competition between cropping system treatments had a random effects structure that accounted for variability across experimental blocks, plots, and subplots. Differences in weed-crop competition across cropping systems and diversity treatments were described by comparing the estimated marginal means of the competition intensity (iw) and yield potential (a0) parameters with Fisher LSD tests.

All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.6.134. Linear mixed-effects models were fit with the ‘lmerTest’ package35, and the non-linear models with the ‘nlme’ package36. After confirming model assumptions, the estimated marginal means of factors were compared with a Fisher LSD test using the ‘emmeans’ package37. All PCAs were carried out using the ‘factoextra’ package38, and PERMANOVAs using the ‘vegan’ package39.

Results and discussion

Conditioning phase

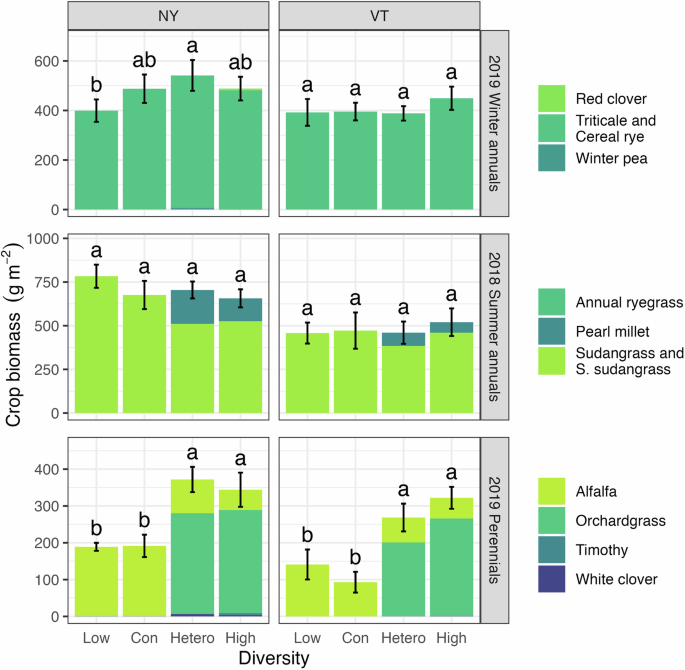

During the last forage harvests of the conditioning phase, crop biomass differed predominantly as a function of diversity treatments in the perennial system (Fig. 2). At both sites, the heterospecific and high diversity treatments had greater total biomass than the low and conspecific diversity treatments in the perennial system (P < 0.05 in the NY site and P < 0.001 in the VT site). Conversely, the diversity treatments only affected crop biomass in the winter annual system at the NY site, with greater crop biomass in the heterospecific compared to the low diversity treatment (P < 0.05).

Crop biomass was compared across diversity treatments within the winter annual, summer annual, and perennial cropping system at each site. Error bars show the standard error of the total mean crop biomass, and different letters within a panel indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). In the figure, ‘Con’ and ‘Hetero’ denote the conspecific and heterospecific diversity treatments. In the legend, ‘S. sudangrass’ is an abbreviation for sorghum sudangrass.

Legume crops seeded in the winter phase of the annual cropping system produced almost no biomass (Fig. 2), and no legumes were grown during the summer annual phase (Table 1). Low functional diversity within the winter and summer phases of the annual system may have contributed to the relative lack of crop biomass variation across diversity treatments in the annual compared to the perennial system. Functional diversity is an important predictor of overyielding40, and past research has found that grass-legume intercrops yield more than monocultures of their grass or legume components41,42.

Uniformity phase

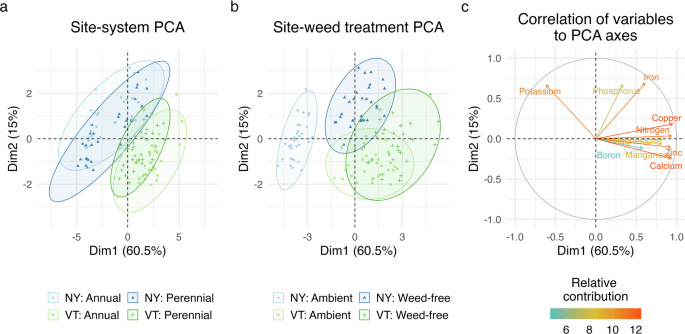

Maize tissue nutrients were assessed to determine if the conditioning phase treatments influenced soil resource availability and if crops and weeds competed for the same nutrients during the uniformity phase. Tissue nutrient composition differed by site, system, and the presence of weeds (P < 0.001; Table 2). Maize tissue nutrients were also affected by interactions between site and system (P < 0.001) and site and weed treatments (P < 0.001). The site-system interaction (P < 0.001) was likely driven by differences in the potassium concentration of maize tissues (Fig. 3a, c). Variation in maize tissue potassium may have been caused by differences in fertilizer applications at the systems level during the conditioning phase. Throughout the three-year conditioning phase, the perennial crops received fertilizer with a greater proportion of potassium than the annual crops (Supplementary Table 1). Correspondingly, mean maize tissue potassium was numerically greater in the perennial system than in the annual system at both sites (Supplementary Table 3).

Maize tissue nutrient composition at the two field sites in annual and perennial systems (a) and the weed-free and ambient-weed treatments (b). Each point in the ordination represents the composite value of 10 tissue nutrient values (nitrogen, calcium, phosphorous, magnesium, potassium, iron, zinc, copper, manganese, and boron) from each sample. The further the points are from each other, the greater the multivariate difference between samples. Plot (c) shows the correlation and relative contribution of each tissue nutrient to the principal components. In the figure axes, ‘Dim’ is an abbreviation for Dimension.

Differences in maize tissue nutrients between the weed-free and ambient-weed treatments indicated that weeds and crops competed for shared belowground resources. The interaction between site and weed treatment was primarily expressed across the first principal component of the PCA (Fig. 3b). The first principal component of the ordination was most correlated to tissue copper, nitrogen, zinc, and calcium (Fig. 3c). At both sites, these nutrients were more abundant in the tissues of maize grown in the weed-free treatment relative to the ambient-weed treatment (P < 0.001; Supplementary Table 3), suggesting that weeds interfered with maize nutrient uptake. These results align with a previous study that found more nitrogen, calcium, and phosphorous in maize tissues grown in weed-free compared with weedy conditions43.

The overlap between weed and crop soil resource use suggests that the resource pool diversity hypothesis can provide a valuable framework for understanding how the legacy effects of intercropping impact weed-crop competition. According to the resource pool diversity hypothesis, intercrops provide a wider variety of soil inputs than monocultures, which reduces weed-crop competition compared to the relatively uniform soil resource pools left by monocultures14. In a crop sequence, it is possible that intercrops leave soil resource legacies that reduce weed-crop competition in future crops. Consequently, if the weed communities in this experiment are similar across crop diversity treatments, it is possible to identify how intercropping affected weed-crop competition through soil resource legacies.

Evaluating weed communities in each treatment describes how weed-crop competition may be influenced by weed community differences rather than the soil resource legacies from intercropping. Although site (P < 0.01) and system (P < 0.05) treatments affected weed communities, there were no differences in weed communities across the diversity treatments (P = 0.57; Table 3). The weed communities at both sites were predominantly composed of warm-season annual species (Table 4).

The lack of weed community differentiation across crop diversity treatments (Table 3) suggests that these treatments were not strong enough filters to affect weed community composition. Past research has also reported little or no differentiation of weed communities after crop rotation44,45 and intercropping46,47. Instead, tillage48,49, crop identity46,50,51, and crop seeding rate52 are often filters of weed community assembly in organic cropping systems. Thus, different tillage and crop identity legacies in the annual and perennial treatments probably contributed to the variation in weed communities observed at the cropping system level. However, the effect of annual and perennial systems on weed community composition was weak (R2 = 0.03; Table 3). Therefore, differences in weed community composition across the uniformity phase had minimal confounding effects on weed-crop competition.

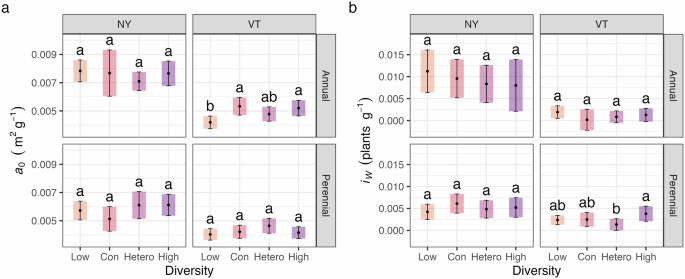

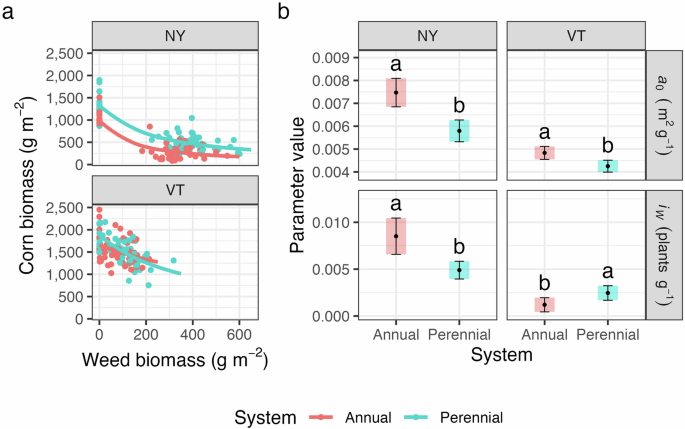

Weed-crop competition in the uniformity phase was evaluated using a hyperbolic yield function based on yield potential (a0; m2 g−1) and competition intensity (iw; plants g−1) parameters. Model parameters only differed as a function of diversity treatment in two instances, neither supporting our hypotheses (Fig. 4a, b). Specifically, yield potential in the VT low diversity treatment was higher than the conspecific and high diversity treatments in the annual cropping system (P < 0.05), and competition intensity was greater in the high diversity treatment than the heterospecific diversity treatment in the perennial cropping system in VT (P < 0.05).

Plots (a) and (b) show the 95% confidence intervals of the yield potential (a0) and competition intensity (iw) parameters, respectively (Eq. 1). Different letters within a panel indicate significant differences in competition parameters (P < 0.05). In the figure, ‘Con’ and ‘Hetero’ denote the conspecific and heterospecific diversity treatments. Note that the lower the a0 parameter, the higher the crop yield potential.

Low functional diversity in the conditioning phase and tillage may have contributed to the lack of crop diversity legacy effects on weed-crop competition. In the winter annuals, legumes were planted in the heterospecific and high diversity treatments, but they accounted for less than 1% of crop biomass (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the summer annual treatments only included grass species (Table 1). As a result, the treatments with interspecific diversity (i.e., heterospecific and high) in annual crops had less functional diversity than in the perennial crops, where grass and legume species were established successfully (Fig. 2). However, the similarity in weed-crop competition across the majority of perennial diversity treatments (Fig. 4) more broadly suggests that the legacy effects of crop diversity on weed-crop competition may not persist after intensive tillage.

To ensure the establishment of maize during the uniformity phase, the entire experimental area was moldboard plowed, disked, and harrowed at the end of the conditioning phase. Tillage impacts plant-soil interactions53 by homogenizing soil niches54,55 and reducing soil microbe diversity55,56. Thus, changes to soil niches and plant-soil interactions from intensive tillage at the beginning of the uniformity phase may have weakened possible diversity treatment legacy effects in the perennial system.

In partial alignment with our hypotheses, competition intensity differed between annual and perennial cropping system treatments (Fig. 5). However, the effect of cropping system was not consistent between sites. Specifically, competition intensity was lower in the perennial system than in the annual system at the NY site, but it was greater in the perennial system at the VT site (P < 0.05; Fig. 5b). Total weed biomass may have influenced competition intensity at the two sites (P < 0.05; Fig. 5a). A high amount of weed biomass was not achieved at the VT site. Consequently, the competition intensity at this site was likely driven by differences in crop yield potential, with the perennial system exhibiting higher yield, resulting in more intense competition (Fig. 5b). Instead, a high amount of weed biomass was achieved at the NY site, causing the competition intensity parameter to more accurately reflect crop tolerance to weed competition (Fig. 5a). Here, there was evidence that maize grown in soils with perennial crop legacies was more tolerant to weed competition than maize grown in soils with annual crop legacies (P < 0.05; Fig. 5b).

Plot (a) illustrates the competition curves at the two sites. Plot (b) shows the 95% confidence intervals of yield potential (a0) and competition intensity (iw) parameters (Eq. 1). Different letters within a panel indicate significant differences in competition parameters (P < 0.05). Note that the lower the a0 parameter, the higher the crop yield potential.

In both sites, soils conditioned by perennial crops had maize with a higher yield potential than soils conditioned with annual crops (P < 0.05; Fig. 5b). A legacy of legumes in the perennial system relative to the annual system probably increased maize yield potential. Research indicates that maize receives nitrogen from decomposing alfalfa57,58. Correspondingly, when maize tissue nitrogen differed across cropping systems, it was higher in the maize that grew in the perennial cropping system treatment (P < 0.05; Supplementary Table 3), which had a legacy of alfalfa during the conditioning phase (Fig. 2). The higher yield potential in the perennial system could also be attributed to differences in soil pathogen load between the cropping systems because crops grown in soil conditioned by a taxonomically similar species may encounter a higher abundance of soil pathogens21,59. Consequently, a legacy of successful legume establishment in the perennial system may have provided soils with increased nitrogen and reduced soilborne pathogens relative to the annual system.

Conclusion

We hypothesized that weed-crop competition would be lower in soils conditioned with higher levels of crop diversity. However, diversity treatments had minimal effects on weed-crop competition. In the annual system, the dominance of grasses may have homogenized inputs to the soil resource pool, leading to similar weed-crop competition across the diversity treatments. Yet, in the perennial intercrops, grasses and legumes were established during the conditioning phase, but no differences were found in weed-crop competition intensity between low- and high-diversity treatments during the uniformity phase. Thus, greater plant functional diversity might be required to establish crop diversity legacies that can endure intensive tillage.

Compared to the diversity treatments, there were more substantive differences between the crop management of the annual and perennial treatments, such as tillage, fertility, and harvest frequency during the conditioning phase. Here, we demonstrate that management decisions at the cropping system level can leave legacies that impact weed-crop competition in future crops. Specifically, we show that by establishing legumes, farmers can condition their soils to increase maize yield potential and, in scenarios of high weed biomass, increase crop tolerance to weed competition. To help farmers use crop diversity to impact weed-crop competition, future research should investigate how crop diversity legacies impact weed-crop competition at different tillage intensities.

Responses