Leveraging the collaborative power of AI and citizen science for sustainable development

Main

The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were launched in 2015 to steer global development efforts towards achieving sustainability by 2030 (ref. 1). However, as this deadline approaches, many countries have failed to produce the data needed to track progress in SDG achievement. For example, data are still lacking for around half of the 92 environmental SDG indicators2, while only 15% of targets are on track to be met by 2030, with all SDG targets having insufficient data3. Other issues include poor data quality, lack of data sharing, infrequent data collection and the lack of disaggregated data, which makes the targeting of local interventions difficult3,4.

To address these challenges, attention has turned to the use of alternative data sources, such as remotely sensed data, mobile data and citizen science4. Successful examples that use data from citizen science have already been demonstrated for SDGs 3, 11, 14 and 15 (ref. 5), with increasing interest from the UN and National Statistical Offices (NSOs) to engage with citizen science initiatives6. However, barriers related to perceived data quality, the lack of data representativeness, the lack of awareness of citizen science, the capacity to handle these data and the absence of national legal frameworks continue to hinder the integration of citizen science data into SDG monitoring and reporting7.

In parallel, recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) through the emergence of new generative AI tools have created considerable interest in understanding how AI can benefit sustainable development and overcome many of the data challenges faced by NSOs and international organizations8,9,10. AI has the potential to enhance human well-being, boost economic productivity, foster innovation and assist in addressing major global issues, including hunger, climate change, health and education, all of which are relevant to SDGs11. However, the use of AI also comes with many challenges and risks, including the financial and environmental costs and unequal access to technology, but there are also biases in the data used to train the models, which can lead to the creation of unreliable responses (so-called hallucinations) and even the generation of deliberate misinformation8. Citizen science can help overcome some of these challenges by providing data that recognize the unique characteristics of local contexts and increase public engagement with the technology while addressing large data gaps in the SDG framework12.

In this Perspective, we examine the roles that AI and citizen science have and could play in the context of the SDGs, and how their integration can address barriers and risks related to their adoption. First, we consider the ways in which AI technologies are and could be integrated into citizen science initiatives, now and in the future, particularly in light of recent developments in generative AI. We then discuss the converse situation, highlighting the need to incorporate citizen science methodologies into AI systems, which could address challenges relevant for use of AI technology for the SDGs. Finally, we present a roadmap for harnessing the collaborative power of AI and citizen science for sustainable development.

AI and the SDGs

AI has been around for decades in the form of different machine-learning algorithms that can learn from data or previous experiences to make predictions or acquire new knowledge13. Yet two recent advances have firmly enhanced AI’s capabilities. The first is deep learning, which allows machines to learn from vast amounts of data in a way that produces outputs that resemble human learning14. Deep-learning models can recognize complex patterns in images, sounds, text and other data. Uses of deep-learning methods include image and facial recognition, speech recognition and self-driving cars15. The second is generative AI, whose systems are built from large collections of text and images and can be used to generate new data by analysing and creating textual and visual content, and for problem solving through conversational interaction with pre-trained systems such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT. Note that here we use the term AI broadly to refer to both past and more recent advances.

Exploring the potential of AI for the SDGs has become a recent topic of interest in the context of AI for Social Good16 as well as drawing the attention of the UN (for example, ref. 17), other international organizations and NSOs. AI can potentially support these communities by enhancing data accessibility, data gathering, task automation, real-time data access, improved data visualization and more-precise insights through reduced costs10. More specifically, AI may help to better monitor poverty18, improve agricultural practices and relevant environmental outcomes addressing hunger and climate action19, map and monitor marine plastic debris density20 and forecast asylum-related migration flows21, all of which are relevant to the SDGs. Focusing on the SDGs, a database compiled by ref. 22 on AI for social good initiatives indicated that all 17 SDGs could be tackled by AI while ref. 23 demonstrated that 134 out of 169 SDG targets could be achieved through the use of AI. However, this potential remains largely unexploited, and there exist substantial challenges associated with AI implementation.

Citizen science and the SDGs

Citizen science, a term coined in the mid-1990s24, encompasses a diverse range of public participation in scientific research and knowledge production activities. From community-led initiatives addressing local social concerns to large-scale environmental scientist-led projects12, citizen science has been growing in recognition in recent decades. Benefits of citizen science in relation to the SDGs include empowering individuals and communities, including those who are traditionally left behind; informing policies at local, national and global levels, helping to achieve more democratic decision-making; and facilitating transformative change by raising awareness and mobilizing action on societal challenges25.

More specifically, current and potential future contributions of citizen science to the SDGs are widely recognized, both in the scientific literature and among the official statistics community. For example, in their systematic review of SDG indicators and citizen science projects, ref. 5 found that citizen science data can support the monitoring of 33% of the SDG indicators, covering all 17 SDGs. In addition, 85% of the health and well-being-related SDG indicators can benefit from citizen science data26. Because of this potential, citizen science has gained substantial momentum among policymakers and the official statistics community in recent years. For example, citizen science data have been integrated for the first time as official statistics to monitor the marine plastic litter SDG indicator in Ghana and reported to the UN SDG Global Database6. In addition, in response to a decision made by the UN Statistical Commission at its 54th session, the UN Statistics Division and partners established the Citizen Data Collaborative to promote and advance the use of data generated by individuals and communities for SDG monitoring and impact27. Yet as with AI, the potential of citizen science for the SDGs is still being exploited in only a handful of case studies, and citizen science is not without challenges, as highlighted in the challenges and limitations section.

Integration of AI into citizen science

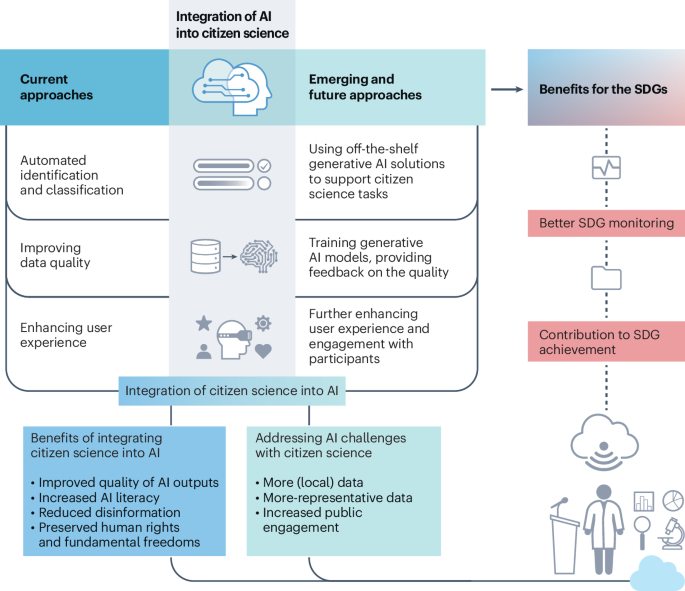

AI is already being used in numerous citizen science projects28,29 although mainly via machine-learning and deep-learning approaches, in particular through automated identification and classification of data30 (Fig. 1). For example, computer vision approaches are used in PlantNet and iNaturalist to automatically recognize species from photographs31,32,33 while GalaxyZoo uses machine learning to classify galaxies, trained using data collected through manual classification by the participants34.

There are two approaches to integrating AI and citizen science: (1) integrating AI into citizen science and (2) integrating citizen science approaches and principles into AI. While the current approaches to the former include automated identification and classification, improving data quality and enhancing user experience, the emerging and future approaches to this integration would benefit from the most recent developments in AI, namely, generative AI. Similarly, there are notable benefits to integrating citizen science approaches and principles into AI such as the improved quality of AI outputs. Citizen science approaches can also assist in addressing the challenges and risks of AI by, for example, providing more and local data. Overall, this integration can benefit sustainable development and the SDGs by substantially improving both their better monitoring and achievement. Credit: Reproduced with permission from Carlos Gaido.

Improving data quality is another way in which AI is currently used in citizen science initiatives (Fig. 1). For example, eBird, which records bird sightings, habitat use and trends, uses machine learning to automatically detect anomalies, categorizing them as errors or potentially useful information35. Participants also provide feedback on the quality of the automated classifications in PlantNet, iNaturalist and GalaxyZoo, thereby further improving data quality and algorithms.

A third way in which AI is being integrated into citizen science is to enhance user experience (Fig. 1). In the BeeWatch project, for example, volunteers submit photos and other information on bumblebees and are provided with automated feedback on their submission using natural language generation technology to improve their volunteer species identification skills and to enhance their experience with the project36. SciStarter, the world’s largest catalogue of citizen science projects, uses machine learning to provide personalized project recommendations for its users based on their historical interactions with the platform37.

Generative AI, however, represents a new opportunity for citizen science projects, which could include integrating off-the-shelf generative AI models into citizen science projects to support the tasks undertaken by citizen scientists in conversational mode or for automated classification (Fig. 1). Another future application may involve additional targeted training of a generative AI model through retrieval-augmented generation38 by adding text or visual content that will improve the model for a specific citizen science task. Participants can then provide feedback on the model outcomes, further improving their performance. This may also address some of the challenges of AI such as societal biases covered in the next section.

Finally, generative AI could be used to automate communication with citizen scientists, providing updates, instructions, training and feedback in a more personalized and efficient way (Fig. 1), similar to how machine learning is improving the user experience in current projects30. Moreover, generative AI could help citizen science projects to attract, engage and retain participants, a recurrent problem faced by many projects39, by generating interesting content, such as social media posts, videos, stories, visualizations and newsletters.

Future developments in AI and citizen science are likely to bring a wealth of new opportunities and varied applications in addition to the ones that are outlined here. For example, generative AI can change how citizen science applications are developed and transform how citizen scientists interact with them, transitioning these applications from static to conversational interfaces.

The need to integrate citizen science into AI

Although ref. 23 identified 134 SDG targets that AI could help to achieve, they also found that the application of AI could impede 59 SDG targets. For example, the use of AI may result in the need for much higher job qualifications, which would widen the already-existing inequalities and prevent the relevant SDGs from being met. Here we discuss some of these AI challenges and the role citizen science approaches can play in helping to address them.

Lack of local data

Large amounts of data are needed to train AI algorithms, yet a lack of data is a prevalent issue in many parts of the world, particularly in the Global South. For example, in 2023, 40% of SDG indicators in the Asia and Pacific region had no data available, while 10% lacked sufficient data with only one data point available40. Where data are available, they are often poorly disaggregated by location, sex, gender, disability or other factors, making it challenging to understand the disparities that exist between various demographic groups in society and to make interventions targeted at those most in need41.

In the context of AI and SDG monitoring, the lack of data can result in the use of algorithms that were trained using data that does not consider specific local circumstances. Consequently, this could compromise the accuracy of the findings, introduce biases, increase hallucinations and widen already-existing disparities between the Global North and the Global South, as well as within and between countries42. To illustrate this, a recent study has shown that an AI algorithm created in Europe can identify marine plastic litter along the coastline of Ghana using drone imagery. This can support the relevant SDG monitoring activities under SDG 14, Life Below Water, and address key policy gaps in the country. The same study highlights the importance of effectively identifying context-specific litter items by refining the algorithm with more and local data, since the results derived from these data could result in substantial policy implications. More specifically, while this is uncommon in Europe, drinking water is stored and sold in water sachets in Ghana. The algorithm that was developed in Europe will not be able to recognize this specific item unless trained with local data. Therefore, more and local training data are needed for the algorithm employed so that it can accurately recognize and classify such items that are specific to the local context43.

Citizen science approaches can help to mitigate the issue of lack of local and representative data and increase the accuracy of AI algorithms when their potential limitations and challenges, elaborated later, are addressed12. Citizen science can improve both the availability and quality of data in a more cost-efficient way for SDG monitoring compared with traditional data sources, such as censuses and surveys4. Citizen science approaches can be even more beneficial in addressing the risk of growing disparities due to a lack of local data, particularly when it comes to the Global South and the marginalized and hard-to-reach individuals and communities. For example, because citizen science initiatives are conducted primarily at local and community levels, they can collect data that take into account the unique circumstances and nuances of the local area44,45.

More specifically, in the context of the aforementioned citizen science project in Ghana, participants collect litter from their local beaches, classifying, counting and recording each litter item they find by litter type6. These kinds of data, gathered by citizen scientists in the field, are critical for understanding and enhancing the accuracy of the AI algorithm to be employed in the second stage of the project, which, if funded, will involve producing litter density maps for the entire coastline of Ghana using drone imagery and AI. Participants will contribute by classifying the drone imagery using an application for rapid image classification. This will provide input data to the AI algorithm for recognizing local items, thereby further addressing the issue of the lack of local data and enhance its accuracy43,46 (Box 1).

Societal biases

AI, in all its forms, can exhibit and emphasize biases that exist in society, such as race, colour, gender, disability and ethnic origin. A variety of factors can cause bias in AI models, such as the use of data that are biased to train AI algorithms. Such biases are known to exist in the literature and to influence AI outputs47,48. Specific examples include some AI products connecting the word ‘Africa’ with poverty, or ‘poor’ with dark skin tones, as well as portraying housekeepers as people of colour and flight attendants as women, and in proportions that can exceed actual observations49,50.

Citizen science approaches can be leveraged to address such biases by increasing the availability of data that reflect realities rather than prejudices. Citizen science can also offer disaggregated data by location, gender, disability, race and other demographic aspects that are currently lacking but are crucial for achieving the ‘leaving no one behind’ principle of the SDG agenda51. To ensure inclusiveness and address potential biases in their methods, many citizen science projects go above and beyond to engage with underrepresented and vulnerable individuals and communities52. Examples of their practices include organizing community events, and interacting with community leaders and other key stakeholders; translating project materials such as mobile phone applications into multiple languages spoken by their target groups in the same country or neighbourhood; utilizing data sheets and pens in addition to smartphone applications and other technologies to ensure participation of individuals with varying degrees of access to such technologies; using voice-recording services or images for those who are illiterate to report data; and incorporating sign languages for the hearing impaired12,53. Furthermore, many citizen science projects collect demographic data from their participants to determine whether they are able to create a truly inclusive project and representative results54.

All these practices can help to improve the representativeness of the input data used to train AI algorithms for high-accuracy outcomes. In addition, citizen science approaches can be used to test the accuracy of the AI algorithms as a quality assurance and control measure. For example, citizen science projects could be implemented to enable individuals to report instances of bias and discriminatory outcomes that they encounter when using AI tools, similar to the Public Editor project (https://www.publiceditor.io/). In Public Editor, following some training, citizen scientists identify biased ideas and messaging in the daily news and report on any material they believe to include biased thinking and messages. Such an approach can be utilized to encourage the public to report instances of biased behaviour that they encounter in their daily lives—this time in AI applications. This can assist in tracking bias and potential human rights violations in AI at larger scales, holding those who have developed such AI applications accountable, and eventually aid in improving these and future applications (Box 1).

Lack of public engagement

AI typically lacks public engagement, which is important to ensure representativeness, reduce biases and enhance the quality of AI results55. However, despite AI having an increasing impact on everyone’s lives, few people are making major decisions about its growth. This is a social justice issue that requires the involvement of a much larger range of people in the discussion and development of AI, especially in the Global South and those who are typically marginalized56. Global-level efforts on governing AI to ensure its ethical and responsible use explicitly call for multistakeholder partnerships involving everyone, especially local communities, in discussions related to AI development, use and governance9,10,56. Such multistakeholder partnerships can be established through the integration of citizen science methodologies, especially those that involve co-creation, into AI. This aspect is important to ensure inclusive partnerships that engage everyone, particularly those who are typically marginalized and harder to reach.

By meaningfully engaging the public in AI development and use, citizen science can also be an effective means to fight against misinformation (unintentional) and disinformation (intentional) (https://www.publiceditor.io/). As AI penetrates our daily lives, disinformation will have an increased impact on fundamental freedoms and human rights by undermining people’s privacy and democracy, which are the guiding principles of the SDGs. More specifically, people are already being misled by the widespread dissemination of disinformation created by generative AI57,58. For example, events during the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in an infodemic—an abundance of information about an issue that spreads misinformation, and disinformation, impeding an efficient public health response and fostering misunderstanding and distrust among the population according to the World Health Organization59. In fact, according to the World Economic Forum, AI-related misinformation and disinformation are considered to be the second greatest global challenge that is likely to worsen in the short term60. The potential of AI for addressing global challenges and for achieving the SDGs can be achieved only if AI systems can be trusted. Citizen science approaches, through engaging the public and all relevant actors in AI initiatives and AI-related conversations, can help to increase media, information and AI literacy among the members of the public (Box 1).

Integrating citizen science and AI for the SDGs

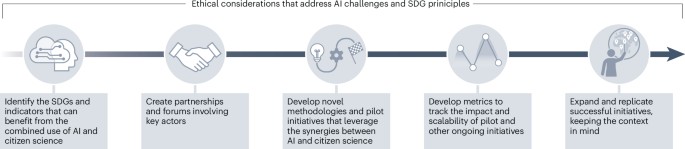

A roadmap outlining five stages for effectively integrating AI and citizen science in the context of the SDGs is provided in Fig. 2. In the initial stage, SDGs, targets and indicators that could benefit from the combined application of AI and citizen science will be identified. This will draw on relevant literature to examine how citizen science can contribute to the SDGs5,26 and the potential impact of AI on the SDGs16,23 as well as expert consultations and workshops.

Roadmap for integrating AI and citizen science for SDG monitoring and reporting. Credit: Reproduced with permission from Carlos Gaido.

The second stage will forge partnerships that facilitate collaboration among key stakeholders, including the UN and other international organizations involved in the SDGs, citizen science practitioners, researchers, AI developers, representatives from NSOs, policymakers and the public. Establishing a platform, such as a community of practice, where these diverse actors can exchange ideas, knowledge and resources to harness the synergies between AI and citizen science while addressing their respective challenges can unlock the collective potential of both domains and foster trust in AI and citizen science among stakeholders.

In the third stage, novel methodologies and pilot projects that leverage the synergies between AI and citizen science will be implemented. Based on available resources, these initiatives can be piloted across various geographical locations and contexts. For example, collaborative projects can be initiated with local communities to align AI technologies with their specific needs, achieving societal benefits as outlined by ref. 61.

In parallel with the third stage or as a subsequent fourth stage, metrics will be developed to evaluate the impact and scalability of the pilot projects in terms of project outcomes, community engagement and the effectiveness of existing AI solutions and citizen science practices. These metrics will draw on insights from established impact assessment frameworks in citizen science and other relevant fields, taking into account UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) recommendations62 and global efforts such as the UN AI Advisory Body report on Governing AI for Humanity9.

The final stage entails replicating and expanding successful initiatives while considering the unique characteristics of local contexts. Throughout all stages of the roadmap, ethical considerations must be upheld in accordance with established guidelines such as the UNESCO Recommendations on the Ethics of AI, the EU Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI and its assessment list, and similar guiding frameworks, emphasizing inclusivity, transparency, human agency and other key principles.

Challenges and limitations

In this Perspective, we have examined the synergies between citizen science and AI and how they can collaboratively boost efforts to monitor and achieve sustainability. We also discussed some of the challenges of AI and how integrating citizen science can help tackle them. We acknowledge that there are additional AI-related challenges than those presented here, such as the lack of infrastructure and skill gaps to deploy AI technologies, particularly in the Global South, as well as the environmental cost of AI due to its high energy demands63. Here, however, our focus is on challenges that can be addressed through citizen science approaches.

It is also crucial to recognize that citizen science itself has its own challenges. For example, the lack of infrastructure, especially in the Global South, poses a challenge not only in the context of AI but also within citizen science. Moreover, limited resources, especially funding, represent a major barrier to initiating and maintaining citizen science projects, particularly in a developing world context7. Raising awareness about the potential of citizen science among funding and policy communities through networking can help to address this challenge to some extent64. In addition, supporting innovative funding mechanisms in partnership with both the donor community and public and private sectors can help tackle this issue10. By fostering partnerships, and creating more and accessible funding opportunities, it is possible to enable citizen science initiatives with broader and more-inclusive participation in resource-limited contexts.

In addition, societal biases related to AI may worsen if potential biases in citizen science projects are not mitigated during this integration. Addressing bias in citizen science can be achieved by ensuring diverse participation through inclusive strategies, verifying data accuracy through robust management practices, and maintaining transparency throughout the citizen project life cycle. Just like citizen science can help to address AI biases, AI can also address biases in citizen science by, for example, analysing anomalies or patterns in participant demographics in citizen science datasets.

Some potential biases in citizen science projects may be related to sociocultural and economic barriers that hinder participation in citizen science activities in developing contexts65. These barriers include limited access to technology, travel costs, participant literacy, language differences and a lack of trust or confidence among participants66,67. In addition, there may be resistance to engagement due to participants feeling overwhelmed or having health and safety concerns. Reluctance to share data due to privacy issues and worries about how authorities might use these data can further limit participation68. To address these challenges, it is essential to build trusted relationships with participants and design projects that are culturally relevant and context-specific69. For example, while volunteering for scientific or environmental causes may resonate in Western contexts, focusing on solutions to environmental and societal issues may be more impactful for recruiting participants in developing countries66. Involving multiple stakeholders, such as funders, policymakers and communities, from the outset, along with an emphasis on community knowledge and participant needs, and using adaptive, low-tech methods and tools that suit the local context, as well as compensating participants when possible, can effectively help overcome these barriers25. Such considerations specific to developing contexts can help to address biases in citizen science itself, supporting the mitigation of AI biases during the integration of citizen science and AI.

For citizen science to effectively address the challenges and potential risks of AI, as well as leverage its potential to achieve sustainable development and the SDGs, there must be a greater focus on increasing engagement, particularly in the Global South. This can be achieved only through appropriate incentives, genuine funding support and attentive project design that takes local contexts and specific needs into consideration12. For example, fostering deeper engagement by understanding participants and their needs is essential for increasing and sustaining involvement in citizen science projects. While external motivation such as awards or career opportunities may be needed initially, especially in countries with low-participation cultures, long-term engagement can be achieved by encouraging intrinsic motivation, including enjoyment, interest or helping society. Incorporating aspects such as promoting a sense of connection to others, providing positive feedback to participants and allowing flexible participation modes are examples of how this could be realized70. In addition, building creative interactions and networks to engage people with nature and designing with inclusion of local realities and people’s concerns is essential for achieving engagement at a larger scale71,72,73.

The substantial data requirements of AI highlight the importance of open data for training models. For citizen science data to effectively address AI challenges, they should be openly accessible. Many citizen science projects strive for open data74. For example, the European Citizen Science Association’s Ten Principles of Citizen Science highlight the importance of citizen science project data and metadata being made publicly available where possible. However, open data may not be a general practice in all citizen science projects due to various reasons such as resource constraints, lack of capacity in data management practices, privacy concerns, respecting the principle of citizen and community ownership of data or not revealing the exact location of an endangered species12. Balancing the openness of data in citizen science with ethical considerations is crucial to fully leverage the potential of both citizen science and AI for addressing sustainability challenges. Similarly, the openness of AI is also an issue. The technical complexity of AI models and the dominance of corporations in the field create black boxes, hindering transparency in their decision-making75. Even supposedly open-source AI models often use restrictive licenses76. This lack of transparency of AI raises further concerns and hinders the full potential of AI for sustainable development. Therefore, advocating truly open and transparent AI models is crucial.

Future directions

Given the data and monitoring challenges associated with achieving the SDGs by 2030 and sustainable development more generally, leveraging the synergies between citizen science and AI is critical for making progress in this arena. We believe this collaborative approach has the capacity to revolutionize data collection, enhance public engagement and accelerate progress towards a more-sustainable future, provided that the challenges and risks associated with both AI and citizen science are carefully considered and addressed.

As a future direction, we recommend following the steps of the roadmap presented in the preceding with particular attention paid to the ethical considerations. Our focus in this Perspective was to articulate specifically how the challenges of AI can be addressed by citizen science, but future research should also focus on exactly how AI can help to mitigate the diverse challenges posed by citizen science methods. Future research can also investigate the current landscape of data openness in citizen science and AI to optimize the quality of AI applications in the context of the SDGs.

Finally, in light of the recent adoption of the Pact for the Future, which encompasses a Global Digital Compact, the first global framework for digital cooperation and AI governance that highlights the importance of AI in achieving sustainability77, we urge all relevant actors, especially the UN and policymakers, to embrace the perspective and vision outlined in this paper to promote the advancement of AI through citizen science.

Responses