Life stage impact on the human skin ecosystem: lipids and the microbial community

Introduction

The skin is the body’s largest organ and serves critical structural, sensing, protective, and thermoregulatory functions. Embedded within the skin are multiple diversly functional appendages, including the sebaceous gland, that define regional environs and allow the skin to maintain its physiological function1. Sebaceous secretions (sebum) are deposited onto the skin’s outermost layer (the stratum corneum), moisturizing skin and influencing the skin’s microbial population2,3. Sebum is composed largely of triglycerides of saturated and unsaturated C16 and C18 fatty acids, wax esters, squalene, free fatty acids (FAs), cholesterol, and cholesterol esters4,5. Skin microbes secrete lipases that digest triglycerides, releasing free FAs6,7,8.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are essential in humans, and exclusively nutritionally sourced. PUFAs, such as omega-3 and omega-6 FAs, are enzymatically and non-enzymatically oxygenated into oxylipins, a diverse class of non-structural, soluble lipid mediators. The enzymatic production of oxylipins is catalyzed mainly by lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, and cytochrome P450 families9,10. PUFA substrates for lipid mediator synthesis are obtained either through de novo production following repetitive elongation and desaturation steps or from host secretions rich in unsaturated C16 and C18 lipids4,5,9,11.

Oxylipins are characterized by having strong immuno-modulatory functions and are well documented to be involved in complex interkingdom host-microbe cross-talk in fungal plant pathogens12. The potent pro-resolving, anti- and pro-inflammatory effects of certain lipid mediators and their associated receptors are known to regulate epidermal cytokine production and secretion13. For example, several pathogenic fungi, including Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida albicans, are capable of producing prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in vitro, which in turn has been shown to have an anti-inflammatory effect on epithelial cells by modulating IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-10 production14. It has recently been shown that a specific oxylipin, 10-hydroxy-(8)-octadecenoic acid, is secreted by breast implant biofilms and induces global hyper-inflammation15. Secretion of anti-inflammatory lipid mediators by pathogenic fungi could enable immune evasion, leading to fungal persistence and development of cutaneous disease.

Malassezia yeasts are the most frequently detected and highly abundant eukaryotic habitants of human skin, especially on lipid-rich skin regions with high sebaceous gland activity like face and scalp16,17. Further, while amplicon- and shotgun-metagenomics show eukaryotes, primarily Malassezia, to comprise 1-5% of the skin microbiome, depending on niche, the vastly larger size of yeast to bacteria implies that Malassezia represent at least an equal abundance of biomass on sebaceous sites18. Through evolutionary adaptation Malassezia apparently lost the genes necessary for de novo lipid synthesis, relying instead on uptake from the rich source of human-derived sebaceous skin lipids19. Malassezia is well equipped to harvest the lipids they require for metabolism, as they contain multiple copies of the required hydrolytic enzymes. Malassezia globosa for example contains 13 potential genes encoding secreted lipases and phospholipases20. Indeed, Malassezia has been found to not only catabolize epidermal lipids but also to produce several hundred lipidic compounds in vitro, including integral constituents of the skin barrier19. Besides Malassezia, other lipophilic microorganisms such as Cutibacterium and Corynebacterium inhabit the human skin16, thus widening the potential interactive lipid metabolic network and crosstalk between the human host and the microbial community.

While many skin host-microbe interactions are commensal or mutualistic, some are pathogenic, causing harm to the host, including those of Malassezia18,21,22,23. Skin-irritating free FAs and squalene peroxides generated by Malassezia cause dandruff, and in more severe cases, seborrheic dermatitis24,25. Malassezia is also likely responsible for pityriasis versicolor, but the disease pathogenesis is not fully understood21. Malassezia is also associated with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis18,21,22. Outside of a dermatological context, Malassezia exacerbates inflammatory bowel disease by inducing a potent inflammatory response from innate cells harboring a polymorphism in the signaling adaptor CARD926. Malassezia accelerate pancreatic oncogenesis by migrating from the gut to the pancreas, binding mannose-binding lectin receptors and activating the C3 complement cascade27. In addition, Malassezia colonization of the mammary tissue has been shown to accelerate breast cancer by inducing cancer tissue sphingosine kinase 1 expression and stimulating the IL-17A/macrophage axis28. The role of Malassezia-derived oxylipins in these diseases and on healthy skin is unclear and the subject of ongoing research.

The skin environment is a core facet of each skin microbial niche. An individual’s life stage considerably alters the skin’s sebaceous gland activity and hence the skin microbial niche. Adults have higher sebaceous gland activity than pre-pubescent individuals, adult males have higher facial sebaceous gland activity than age-matched females, and pre-menopausal women have higher sebaceous gland activity than post-menopausal women29,30,31. Given that skin microorganisms like Malassezia metabolize sebum lipids, we were curious how differing life stages’ sebaceous gland activities alter the skin lipidome and microbiome of healthy individuals, so we assessed the skin oxylipin content by mass-spectroscopy and the microbial population by shotgun metagenomics. To determine lipid mediator origin as host or microbial, in vitro keratinocytes and Malassezia mono- and co- cultures were performed. In addition, cytokines from the mono- and co-cultures were assessed to determine correlations between lipid mediators and cytokines. This study reveals novel associations between three axes: an individual’s biological age, their skin lipidome, and their skin microbiome.

Results

Skin oxylipin and microbiome composition are significantly different between pre-pubescent and adult subjects

Skin sebaceous gland activity is higher in adults versus pre-pubescent individuals and in pre-menopausal versus post-menopausal women29,30,31. We hypothesized that changes in sebaceous gland activity based on an individual’s life stage would regulate their skin oxylipin profile, microbial diversity, and microbial abundance. Because skin microbes metabolize sebum lipids and secrete oxylipins5,19,20 we also hypothesized that the skin’s oxylipin content will be impacted due to its link to the skin’s microbial community.

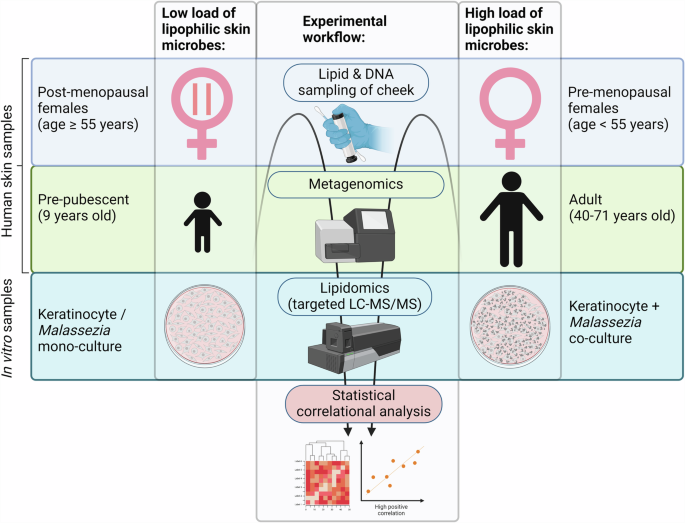

To test these hypotheses, we sampled the cheek skin surface of 100 adult (HELIOS)32 and 36 pre-pubescent (GUSTO)33 subjects for oxylipins and microbes using LC-MS/MS lipidomics and shotgun metagenomics, respectively. Concurrently, we acquired subject metadata including age, gender, ethnicity, skin sebum quantity (adults only), and blood hormone concentrations (adult females; E2, FSH, and LH) (see Supplementary Table 1). To differentiate oxylipins secreted by the skin cells from those secreted or modified by skin microbes, and to ascertain their correlations with skin cytokine secretion, we explored in vitro keratinocyte co-cultures with Malassezia, the most abundant fungal genus on skin identified by culture17 and molecular16 methods (Fig. 1).

Microbial biomass and lipid samples were acquired from the cheek skin of pre-pubescent (GUSTO) and adult (HELIOS) subjects. Post-menopausal and pre-menopausal woman were classified based on age. Skin lipid samples were analysed using targeted LC-MS/MS. Skin microbial samples were analysed using shotgun metagenomics. Culture supernatants of keratinocyte and Malassezia monocultures and keratinocyte-Malassezia co-cultures were analysed using targeted LC-MS/MS for lipid mediators and ELISA for cytokines. Correlational analyses were performed for lipidomic/metagenomic and lipidomic/cytokine data. Figure created with BioRender.com.

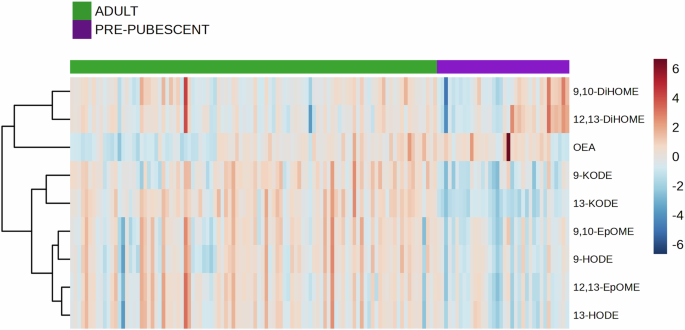

Eight oxylipin species and one lipid amide were quantifiable from the cheek skin surface (Supplementary Table 1). Hierarchical clustering revealed that the majority of oxylipins were elevated on adult versus pre-pubescent skin (Fig. 2). Six oxylipins were significantly elevated on adult versus pre-pubescent skin: 9-HODE (p = 0.0006; false discovery rate [FDR] = 0.0002), 13-HODE (p < 0.0001; FDR < 0.0001), 9-KODE (p < 0.0001; FDR < 0.0001), 13-KODE (p < 0.0001; FDR < 0.0001), 9,10-EpOME (p < 0.0001; FDR < 0.0001), and 12,13-EpOME (p < 0.0001; FDR < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Two of the quantifiable oxylipins were not significantly different: 9,10-DiHOME (p = 0.2086; FDR = 0.0547) and 12,13-DiHOME (p = 0.6817; FDR = 0.1591). The lipid amide oleoylethanolamide (OEA) (p = 0.0013; FDR = 0.0004) was significantly elevated on pre-pubescent versus adult skin.

Skin tape strips of the cheek from the HELIOS and GUSTO cohorts were analysed using targeted mass spectrometry, in which eight unique oxylipins and a single lipid amide were identified. Red and blue heat-map tiles indicate higher and lower lipid concentrations than the mean. The Euclidean method was used to calculate the distance measures between samples and the Ward method was used for clustering. The data was analysed in MetaboAnalyst77 using lipid data in pg/cm2.

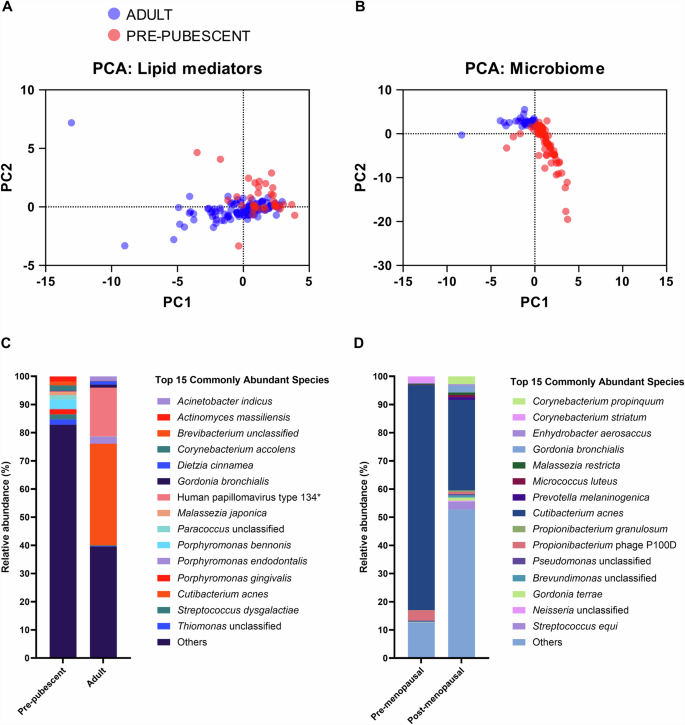

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the quantified skin lipids revealed that most pre-pubescent subjects clustered separately from adults (Fig. 3A). It is likely that as the pre-pubescent subjects were sampled at age 9 and classified as such only by Tanner stage and not hormonal status that the pre-pubescent subjects clustering with adults on the PCA was due to earlier initiation of the sebaceous changes resulting from puberty, as changes in sebum secretion are among the earliest in puberty30,34.

PCA plots based on the (A) nine lipid mediators or the (B) 370 microbial species. Red represents the pre-pubescent (GUSTO; N = 34) and blue represents the adult (HELIOS; N = 100) cohorts. Median relative abundance differences in the top 15 commonly abundant species between (C) pre-pubescent and adult subjects, and between (D) pre-menopausal (N = 25) and post-menopausal (N = 25) women. *Human papillomavirus type 134 was found only on one adult subject at high abundance.

PCA of the 370 microbial species detected on cheek skin (Supplementary Table 2) adjacent to the lipid sampling site revealed distinct clusters between the adult and pre-pubescent cohorts (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the pre-pubescent skin had a higher Shannon Index (Supplementary Fig. 2A), indicating higher species richness (greater number of species detected) and evenness (fewer single-species domination in abundance) on pre-pubescent versus adult skin.

Differences in skin microbiome composition can be attributed to differences in skin physiology. For example, adults have higher sebaceous gland activity than pre-pubescent subjects29,30,31. The lipophilic bacterium Cutibacterium acnes (previously Propionibacterium acnes) was detected at a high relative abundance of 35.9% on adult skin but less than 1% on pre-pubescent skin (Fig. 3C). Moreover, C. acnes was detected on all adult skin but less than 1% of pre-pubescent skin. The lipid-dependent Malassezia spp., M. restricta, was detected on all adult skin, while M. globosa was detected in 79% of sampled adult skin. By contrast, the detection frequency of M. restricta and M. globosa on pre-pubescent skin was drastically lower at 9.41% and 1.18%, respectively.

Pre-menopausal women have higher sebaceous gland activity than post-menopausal women29,30,31. However, while the median cheek sebum concentration of pre-menopausal women in our HELIOS cohort was higher than that of post-menopausal women, the difference was insignificant (p = 0.7743) (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Although the sebaceous gland activity was not significantly different, C. acnes relative abundance was 79.9% in pre-menopausal and 32.1% in post-menopausal women (Fig. 3D), and the species was detected in all sampled adult women. Regarding Malassezia spp., M. restricta and M. globosa relative abundance and detection frequency were similar on pre- and post-menopausal women’s skin (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Table 2).

The human papilomavirus type 134 appears in this data set as abundant in adults. However, we believe this is not a general discovery as the viral species was only detected in a single adult but at an extremely high abundance.

Correlations between skin oxylipins and microbes in the pre-pubescent versus the adult cohort

Human cutaneous epidermal cells and multiple skin-resident microbial species are known to secrete oxylipins35,36,37. However, it is challenging to determine the origin of skin oxylipins due to the complex contribution of the skin microbial community. Therefore, we performed correlational analyses for each microbial species with specific oxylipins detected on the cheek skin of subjects at different life stages to identify potential contributions of skin-resident microorganisms in epidermal lipid mediator metabolism.

A mix of positive and negative correlations was found between microbial species’ and oxylipin relative abundances on pre-pubescent skin (Supplementary Fig. 4A), but primarily positive correlations were detected on adult skin (Supplementary Fig. 4B). On pre-pubescent subjects, M. restricta was negatively correlated with 9,10-EpOME (r = −0.31). On adult skin, M. restricta was positively correlated with 9,10-DiHOME (r = 0.20) and negatively correlated with OEA (r = −0.26). M. globosa was negatively correlated with 9-KODE (r = −0.27), 13-KODE (r = −0.30), 9,10-EpOME (r = −0.20), and OEA (r = −0.33). M. japonica was positively correlated with 9,10-DiHOME (r = 0.23). M. furfur was positively correlated with 9-HODE (r = 0.29), 13-HODE (r = 0.20), 9-KODE (r = 0.29), and 9,10-DiHOME (r = 0.29). Overall, the analyses revealed significant correlations between specific oxylipins and specific Malassezia species between the pre-pubescent and adult cohorts.

Focusing on the most common correlations, we more deeply examined the skin microbes with four or more correlations with skin oxylipins, revealing microbial species of particular interest (Supplementary Fig. 4). On pre-pubescent skin, Streptococcus infantis was negatively correlated with 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9-KODE, 13-KODE, 9,10-EpOME, 12,13-EpOME, and 12,13-DiHOME. Brevibacterium massiliense was negatively correlated with 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9,10-EpOME, 12,13-EpOME, and 9,10-DiHOME. Porcine type C oncovirus was positively correlated with 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9,10-EpOME, and 12,13-EpOME. Human adenovirus D was positively correlated with 9-KODE, 13-KODE, 9,10-DiHOME, and 12,13-DiHOME and negatively correlated with OEA. On adult skin, M. globosa was negatively correlated with 9-KODE,13-KODE, 9,10-EpOME, and OEA. M. furfur was positively correlated with 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9-KODE, and 9,10-DiHOME. Acinetobacter junii was positively correlated with 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9-KODE, 13-KODE, 9,10-EpOME, 12,13-DiHOME, and 12,13-EpOME. Veillonella atypica was positively correlated with 9-HODE, 9,10-EpOME, 9,10-DiHOME and 12,13-DiHOME. Prevotella nigrescens, Filifactor alocis, Eubacterium brachy, Alloprevotella rava, and Porphyromonas endodontalis were positively correlated with 9-KODE, 9,10-EpOME, 12,13-EpOME, and 12,13-DiHOME.

Skin microbiome diversity is linked to menopausal status

The female’s chronological age impacts their skin microbiome38,39,40,41,42,43,44. However, few studies explicitly considered the menopausal status and the skin microbiome45,46. In agreement with previous studies47, pre-menopausal women (N = 25, aged < 55) had higher serum estradiol (E2), lower luteninizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels compared to post-menopausal women (N = 25, aged ≥ 55), enabling confident classification of pre- from post-menopausal women (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Although the skin oxylipins were not significantly different between pre- and post-menopausal subjects (Supplementary Fig. 6), elevated oxylipin abundances in post-menopausal women correlated with greater microbiome richness: Similar to pre-pubescent skin, there was higher overall microbial diversity in post-menopausal skin (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. 2B) and a higher number of correlations between specific oxylipins and specific microbial species compared to pre-menopausal skin (Supplementary Fig. 7). The observed decrease in relative abundance of lipophilic species like C. acnes (Fig. 3D) may be associated with a hormone-induced reduction of sebum secretion common in post-menopausal skin and may account for changes in skin oxylipin profiles.

The Singaporean-Asian ethnicity has a different skin lipid mediator profile but a similar skin microbiome

Few studies have compared racial differences in sebum composition and the results are controversial: Several studies imply significant differences in sebaceous gland activity and sebaceous lipid content between Caucasian, Asian, and American African individuals48,49, but another50 did not. To the authors’ knowledge, no study has yet compared sebaceous lipid secretion between Asian ethnic subgroups. In this study, the analysed adult cohort consisted of a combination of Asian ethnicities, including South Asian (Indian) (N = 20), East Asian (Chinese) (N = 60), and Southeast Asian (Malay) (N = 20). Sebum secretion was elevated in the East Asian group relative to the South Asian and Southeast Asian groups, with a significant difference identified between the highest (East Asian) and lowest (Southeast Asian) groups (Supplementary Fig. 8). We hypothesized that differing sebum quantities should affect the skin microbiome compositions and consequently, the skin oxylipin profiles. However, our study found no significant difference in skin microbial alpha- and beta-diversity between these ethnic groups (not shown), consistent with findings from a previous report17, which did not detect differences in Malassezia species levels between Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Caucasian ethnic backgrounds using culture-based techniques. Nevertheless, we found 9,10-DiHOME concentrations significantly different between Asian subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 9A), suggesting that other extrinsic and/or intrinsic factors may contribute to the divergent 9,10-DiHOME concentration of these different Singapore-resident ethnic groups. Particularly, no oxylipins were significantly different between South Asian and Southeast Asian, while the East Asian skin oxylipin content was significantly segregated (Supplementary Fig. 9B) in direct parallel to the sebum amount.

Malassezia-keratinocyte co-cultures connect lipid mediator production to cytokine secretion

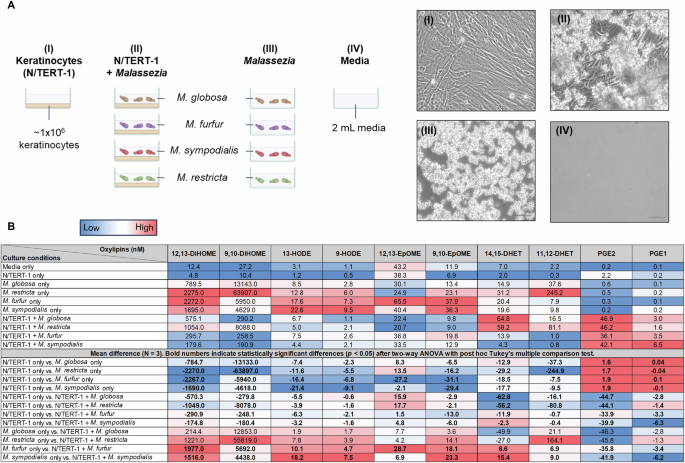

In vitro, Malassezia yeasts produce multiple oxylipins detected on skin37. Since the above correlations do not imply causation, we further investigated oxylipin and cytokine production in a defined 2D in vitro co-culture system with human immortalized keratinocytes (N/TERT-1)51, the primary human epidermal cell type, and four Malassezia species commonly reported on human skin (M. globosa, M. restricta, M. furfur, and M. sympodialis) (Fig. 4A). Optimized co-culture conditions were well tolerated by both Malassezia and keratinocytes, as the yeasts recovered on agar growth plates and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays revealed no significant cytotoxicity, respectively (not shown), after the 24 h incubations.

A Schematic of the co-culture conditions: (I) human immortalized keratinocytes (N/TERT-1) monoculture, (II) N/TERT-1 co-cultures with four different Malassezia spp., (III) Malassezia monocultures, and (IV) mock culture only containing media. Light microscopy pictures show mono- and co-culture conditions between N/TERT-1 and M. globosa. B LC-MS/MS analysis of oxylipins in culture supernatants after 24 h of culture at 37 oC and 5% CO2. Red, white, and blue colours on the heatmap indicates high, medium, and low oxylipin concentration or difference in concentration for a specific oxylipin column. To determine oxylipin concentration differences between mono- and co-cultures, the mean difference was calculated for the three biological replicates and a two-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test was performed. Comparisons with significant concentration difference are indicated in bold numerals.

All four Malassezia monocultures produced high concentrations of 9,10-DiHOME and 12,13-DiHOME, moderate concentrations of 11,12-DHET, and low concentrations of 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 14,15-DHET, and 9,10-EpOME (Fig. 4B). The concentrations of PGE1, PGE2, and 12,13-EpOME were similar to the media-only condition, indicating that Malassezia does not produce these oxylipins in monoculture. The concentrations of these 10 measured oxylipins in N/TERT-1 monocultures were also similar to the media-only condition, indicating that keratinocytes do not produce these oxylipins in monoculture.

PGE1 and PGE2 concentrations in co-cultures were significantly higher than in Malassezia and N/TERT-1 monocultures, suggesting inducible oxylipin production in co-culture. The co-culture concentrations of 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 11,12-DHET, 14,15-DHET, 9,10-EpOME, 9,10-DiHOME, and 12,13-DiHOME were generally lower than in Malassezia monocultures but higher than in N/TERT-1 monocultures, suggesting inhibition of Malassezia oxylipin production or enhanced oxylipin catabolism in co-culture.

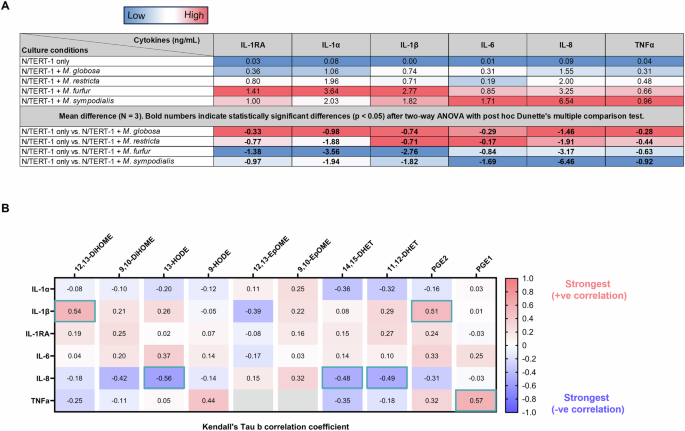

To investigate the potential role of oxylipins in directing the relationship of Malassezia yeasts with the human host, selected cytokines were simultaneously measured in the cultures using an ELISA-based cytokine assay. In agreement with previous studies52, all Malassezia species induced, to different degrees, secretion of all analysed cytokines except IL-10 (not shown) (Fig. 5A). As expected, cytokine production was minimal in N/TERT-1 and undetectable in Malassezia monocultures (not shown).

A Concentration of cytokines produced by N/TERT-1 mono- and co-culture with M. globosa, M. restricta, M. furfur, and M. sympodialis. No cytokines were detected in Malassezia monocultures (data not shown). Red, white, and blue colours on the heatmap indicates high, medium, and low cytokine concentration or difference in concentration for a specific cytokine column. To determine cytokine concentration differences between mono- and co-cultures, the mean difference was calculated for the three biological replicates and a two-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunette’s test was performed using ‘N/TERT-1 only’ condition as control. Comparisons with significant concentration difference are indicated in bold numerals. B Correlations between specific cytokines and oxylipins. Correlations were assessed using Kendall’s Tau b with 5% false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Red indicates positive correlation while blue indicates negative correlation. Correlations with less than 5% FDR are highlighted within teal borders. The correlation strength of ± 0.30 or above is classified as strong.

The significant correlations between Malassezia-induced oxylipins and keratinocyte-produced cytokines in co-culture are indicative of the potential of these yeasts to modulate the skin immune response triggered by keratinocytes (Fig. 5B). IL-1β was strongly and positively correlated with 12,13-DiHOME and PGE2. IL-8 was strongly and negatively correlated with 13-HODE, 11,12-DHET, and 14,15-DHET. TNFα was strongly and positively correlated with PGE1.

Discussion

It is likely that lipid metabolism of specific skin resident microbial species contributes to the human skin lipidome. However, it is currently not possible to specifically alter the human skin microbiome as all known antimicrobial compounds have a significant degree of non-specificity. To investigate the complex connections between sebaceous secretions, the microbial community, and the presence and activity of skin oxylipins, we have probed in detail a diverse human cohort in different life stages and hence with differing skin lipid and microbial content and validated the findings with in vitro skin cell and microbial cultures.

The majority of sebum FA from humans of all ages consist of C16 (palmitic, palmitoleic, and sapienic acids) and C18 (stearic, oleic, and linoleic acids)4,5. As skin surface oxylipins are synthesized from sebaceous FAs and adults have higher sebaceous gland activity than pre-pubescent children29,30,31, adults will have more sebaceous FAs available for oxylipin synthesis, potentially explaining the elevated oxylipin concentration on adult versus pre-pubescent skin (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Higher sebaceous gland activity has also been reported in pre-menopausal versus post-menopausal women29,30,31. Despite having distinctly different menstrual cycle-related hormonal profiles for E2, FSH, and LH (Supplementary Fig. 5), sebaceous gland activity was not significantly different between pre- and post-menopausal women in our cohort (Supplementary Fig. 3A), most likely due to the high inter-individual variability and relatively small cohort size. Consequently, the skin oxylipin content of our pre- and post-menopausal women also did not significantly differ (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Comparing sebaceous gland activity between ethnicities revealed that East Asians (Chinese) had more sebaceous gland activity than Southeast Asians (Malay), and South Asians (Indians) did not differ significantly from the East (Chinese) and Southeast Asians (Malay) (Supplementary Fig. 8). Because the differences in sebaceous gland activities between the ethnic groups were small and highly variable, most skin oxylipins measured, except 9,10-DiHOME, were also not significantly different (Supplementary Fig. 9A). Collectively, we show that the subject’s chronological age significantly perturbs sebaceous gland activity and skin oxylipin content, and these perturbations are pronounced when comparing pre-pubescent to adult subjects but less so when comparing menopausal status and ethnicity.

The skin microbiome changes with chronological age53, and our shotgun metagenomics analyses confirmed the significant differences in the microbial community between pre-pubescent and adult skin (Fig. 3B). Lipophilic C. acnes was more abundant on adult than pre-pubescent skin (Fig. 3C) and lipid-dependent M. restricta and M. globosa detection frequency was drastically elevated on adult versus pre-pubescent skin. C. acnes was also more abundant on pre-menopausal than on post-menopausal women’s skin despite no detectably significant difference in sebaceous gland activity. The increased presence of lipophilic and lipid-dependent microbes on adult versus pre-pubescent skin likely results from the differing age-dependent sebaceous gland activities. Currently available methods for quantifying skin lipid secretion have significant variability, and it is possible that in the menopausal cohort there were undetectable changes in sebum content or quality which still drove detectable difference in the microbial community, or the changes may be due to other host factors which have not yet been identified.

Malassezia yeasts produce many of the same oxylipins found on human skin, raising the hypothesis that these oxylipins are synthesized either through shared metabolic pathways or entirely of microbial origin37. M. restricta was detected on all sampled adult skin but only 9.41% of sampled pre-pubescent skin. The oxylipin 9,10-EpOME is synthesized from linoleic acid, a C18 PUFA, and hydrolysis by soluble epoxide hydrolase yields 9,10-DiHOME. On pre-pubescent skin, 9,10-EpOME was negatively correlated with M. restricta and on adult skin 9,10-DiHOME was positively correlated (Supplementary Fig. 4). This finding led to the hypothesis that M. restricta on skin metabolizes 9,10-EpOME to 9,10-DiHOME. In vitro co-cultures of keratinocytes with Malassezia revealed that 9,10-DiHOME was produced by M. restricta but not keratinocytes (Fig. 4B). Because 9,10-EpOME was not produced by keratinocytes or M. restricta in our cultures, we hypothesize that the precursor on skin was derived from other host secreted lipids, cells, or microbes through metabolic cross-feeding. While 9,10-DiHOME has been reported to induce oxidative stress in endothelial cells derived from porcine pulmonary arteries54, chemotaxis in human neutrophils54, and differentiation of murine regulatory T cells55, its Malassezia-induced role on human skin remains elusive.

PGE2 is implicated in many immune functions and hair growth stimulation56,57. PGE2 concentrations were increased in the in vitro co-cultures but not in the keratinocyte or Malassezia monocultures (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 10). In this study, although Malassezia was found on skin, PGE2 was not detected, likely below detection limit concentrations or high turnover rates of production and degradation. While presence of Malassezia on skin is well known, recently, the fungi have been reported deep within the hair follicle58. Given Malassezia proximity to the sebaceous gland, a direct role in scalp health and hair growth is of interest. By determining if PGE2 is produced by keratinocytes and/or Malassezia, and if production necessitates induction by one another, new microbiology-based hair growth interventions may be explored by promoting the host-microbe interaction.

Oxylipins are known to induce or inhibit inflammatory cytokine production by keratinocytes59. In co-cultures with Malassezia and keratinocytes, 13-HODE, 11,12-DHET, and 14,15-DHET were strongly and negatively correlated with IL-8 production by keratinocytes (Fig. 5B). IL-8 is involved in the killing of Candida albicans60, an opportunistic fungal pathogen that colonizes healthy human skin61, raising the hypothesis that Malassezia-derived oxylipins may repress IL-8 secretion by keratinocytes and thereby antagonize the antifungal effect, permitting persistent colonization. Also in the co-cultures, 12,13-DiHOME and PGE2 were strongly and positively correlated with the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β (Fig. 5B). IL-1β is associated with inflammasome activation in keratinocytes and has a role in immune-related-skin diseases, for example, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis62,63.

The biosynthesis of skin oxylipins is not restricted to Malassezia. Other fungi such as Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, and Aspergillus fumigatus, although far less abundant and frequently detected on skin16, may also produce oxylipins similar to Malassezia14,64,65. It is also noteworthy that changes in relative DNA abundances, as revealed by shotgun metagenomic approaches, do not strictly correlate with absolute microbial abundances. For example, Malassezia has at least 500 times more relative cellular biomass per genome than Staphylococcus epidermidis66. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that a decrease in the proportional abundance of a specific skin microbial species manifests as a proportional change in actual microbial load and consequently microbial enzymatic activity (associated with biomass). Furthermore, human skin contains many cell types with different roles and communication systems, and the highly complex skin microbial community involves inter- and intra-species signalling and biochemical activities with synergistic and/or antagonistic effects on skin oxylipin production. Hence, not surprisingly, a direct translation of findings retrieved from highly controllable in vitro culture systems to physiological environments is not straightforward but are a step in the right direction to query the source of oxylipin biosynthesis and their implications on host cells. Leveraging from this study, there are ongoing efforts to determine how microbially derived oxylipins impact skin cells in culture through direct supplementation.

Comparison of skin oxylipins in humans can also be challenging due to variations in host genetics, diet, and usage of skin care products. For example, South Asian (Indian) skin and hair care traditionally involves the topical application of natural oils derived from olives, sunflower seeds, coconuts, and oats67,68, which are all rich in essential omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, including PUFAs that can impact oxylipin biosynthetic pathways on skin. Moreover, mediated via the gut-skin axis, differing dietary habits can have a substantial impact on the skin lipidome. For example, dietary supplementation of omega-3 PUFA, enriched in e.g. flaxseed oil, a commonly used ingredient in Indian cuisine, reduced the production of arachidonic acid-derived lipids with pro-inflammatory properties in the epidermis69. Therefore, future human studies of the skin lipidome and microbiome should consider potential confounders such as diet and skin product use, stratifying the study cohort as much as practically possible to minimize potential noise and optimize signal in the datasets.

In conclusion, the human biological age and the life stages of puberty and menopause impact skin sebaceous activity, with pre-pubescent children having lower sebum production than post-pubertal adult subjects. Consequently, the skin oxylipins, lipids synthesized from sebaceous lipid precursors, were significantly lower in pre-pubescent versus adult skin. The increased skin sebaceous gland activity in adults also promoted a more lipophilic and lipid-dependent microbiome. In addition, we found multiple strong correlations between the relative abundance of specific skin microbes and specific skin oxylipin species such as 9-HODE, 9-KODE, 13-HODE, 13-KODE, 9,10-EpOME, 9,10-DiHOME, 12,13-EpOME, and 12,13-DiHOME, and the lipid amide OEA. In agreement with these clinical findings, we have also shown that in an in vitro model of Malassezia-keratinocyte coculture, levels of 9,10-DiHOME can be correlated to the presence of these skin-resident yeasts.

While this study only reveals correlational interactions between the skin microbiome and skin oxylipins, the presented results imply a complex host-microbe communication system present on healthy human skin, and that skin health and disease may be influenced by the skin microbial community through microbial or jointly microbial/human cell derived oxylipins. This should encourage further investigations into potentially more directly causative links. Future work should include targeted skin microbial community alterations with specific interventions to clarify the role of specific microbes in the synthesis of skin oxylipins and utilize mass-labeled substrates in co-culture and in vivo experiments to characterize oxylipin biosynthetic pathways. Further definition of these interkingdom communication pathways may reveal novel fundamental biology and targets for intervention design to improve human health.

It should be noted that some aspects of this study were challenging to conduct. For example, the sampling of human skin oxylipins. The surface area of the collection device and the material used is crucial, so that low-abundance oxylipins are quantifiable. While flax paper has been implemented to successfully collect oxylipins from human skin, as shown here and by others37, it was possible that some oxylipins at lower concentration were not detected due to the small sampled surface area and/or its high background noise interference. Additionally, multiple confidently detected oxylipins were unable to be precisely identified due to the lack of commercial availability of authentic analytical standards. It is also possible that study participants did not comply with study guidelines and variations in oxylipin measures may be due to these non-biological factors.

Similar to oxylipin collection limitations, Cuderm D-Squame tapes may not have sufficient mass of sample to detect extremely low abundance microbial species. Furthermore, microbial species detection was dependent on the ever-developing microbial databases used to map sequencing reads. MetaPhlAn2 and PathoScope microbial databases, while comprehensive, lack the genomes of unknown and newly identified species. For example in PathoScope, M. arunalokei and M. vespertilionis were unavailable. Many current microbial genome databases suffer from a lack of Asia-relevant microbial species and strains, potentially contributing to a large fraction of unmapped reads. Addressing these limitations with improved technologies and techniques will refine the findings reported herein.

Methods

Materials

All non-labelled and isotope labelled analytical lipid mediator standards (Supplementary Table 3) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Flax paper (Zig-zac, London, UK) and the Cuderm D-Squame tapes (CatLog no: SKU-D100, Clinicalandderm, MA USA) were used for skin sampling. The Cuderm D-Squame tapes with a surface area of 3.8 cm2 were used to sample for microbial cells from the cheek stratum corneum, while a 1.5 cm2 flax paper overlaid onto the center of a Cuderm D-Squame tape was used to sample for lipids. Keratinocyte serum-free media (K-SFM; Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to cultivate N/TERT-1 cells. MILLIPLEX MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Customised 7-plex Panel (Merck Millipore) was used to quantify cytokine levels.

Sampling of subjects

A total of 100 healthy adult subjects were selected from The Health For Life In Singapore (HELIOS) cohort and constituted of 50 females and 50 males aged 40–71, with different ethnic backgrounds, i.e., 20 South Asian, 60 East Asian, and 20 South East Asian.

A total of 36 healthy pre-pubescent subjects with exclusively East Asian ethnicity were selected from the Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) cohort and constituted of 18 females and 18 males, all aged 9. Inclusion criteria were normal skin with no obvious skin conditions or disease.

Microbial samples were taken from left and right side of cheek by using Cuderm D-Squame tape strips that were pressed 25 times per collection, and either the left or right sample was analysed per subject through DNA sequencing.

Similarly, as previously described37, skin surface lipid samples from the left and right side of cheek were taken by using an absorbent flax paper disc that was applied to the skin sampling site for 5 minutes using Cuderm D-Squame tapes, and either the left or right sample was analysed using targeted LC-MS/MS. All samples were stored at −80 °C until lipidomics and metagenomics analysis.

All volunteers from the HELIOS and GUSTO studies provided written informed consent prior to study commencement and were sampled in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and both studies were approved by the Nanyang Technological University (NTU) Institutional Review Board (IRB-2016-11-030), the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (D/09/021) and SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB 2018/2767; 2009/280/D), respectively. Consent was sought from study volunteers for the publication of their de-identified processed data in strict adherence to the approved HELIOS (IRB-2016-11-030) and GUSTO (CIRB 2018/2767; 2009/280/D) study protocols.

Lipidomic analysis of co-cultures between Malassezia species and human immortalized keratinocytes

Human immortalized keratinocytes N/TERT–151 were obtained and cultured in K-SFM supplemented with 25 µg/ml bovine pituitary extract (BPE), 0.2 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), and 0.3 mM CaCl2, as previously described in ref. 70. N/TERT-1 cells were plated in 6 cm tissue culture plates 2 days prior, to reach 80% confluency. Media was refreshed and keratinocytes separately co-cultured for 24 hours at 37 oC (5% CO2) with 125 µl of exponentially grown and triple-washed Malassezia restricta (CBS 7877), M. globosa (CBS 7966), M. furfur (CBS 7982), and M. sympodialis (CBS 42132) cells equivalent to 0.2 × 106, 0.7 × 106, 3.5 × 106, and 6 × 106 colony forming units (CFU), respectively. The conditioned and co-cultured media were filtered through 0.2 µm filters and stored at −80 oC prior to experimental analysis. Targeted LC-MS/MS analysis was performed as described below, except that the media was diluted and mixed with an equal volume of extraction buffer (116 mM Na2HPO4, 42 mM citric acid, pH5.6) prior to SPE.

Multiplex cytokine analysis of co-cultures

Luminex analysis was performed to measure the targets IL-10, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1Rα, IL-6, IL-8 and TNFα using the MILLIPLEX MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Customised 7-plex Panel as previously described71. Briefly, harvested supernatants and standards were incubated with fluorescent-coded magnetic beads pre-coated with respective antibodies in a black 96-well clear-bottom plate overnight at 4 oC. After incubation, plates were washed 5 times with wash buffer (PBS with 1% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20). Sample-antibody-bead complexes were incubated with Biotinylated detection antibodies for 1 hour and subsequently, Streptavidin-PE was added and incubated for another 30 mins. Plates were washed 5 times again, before sample-antibody-bead complexes were re-suspended in sheath fluid for acquisition on the FLEXMAP® 3D (Luminex) using xPONENT® 4.0 (Luminex) software. Data analysis was done on Bio-Plex ManagerTM 6.1.1 (Bio-Rad). Standard curves were generated with a 5-PL (5-parameter logistic) algorithm, reporting values for both mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and concentration data.

Analysis of lipid mediators using targeted LC-MS/MS

The protocol for lipid mediator extraction from flax paper disks using solid phase extraction (SPE) columns was performed as described earlier37. Briefly, lipids were released from the flax paper disks overnight at 4 °C with 1 mL of methanol (MeOH): water (H2O) (5:95 by v/v) at 900 rpm (revolution per minute) in a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Samples were spiked with 50 μl of a solution containing a mix of the deuterated internal standard listed in Supplementary Table 3. Analytes were extracted using Strata-X 33 µm polymer-based solid reverse phase (SPE) extraction columns (8B-S100-UBJ, Phenomenex). Columns were conditioned with 3 mL of 100% MeOH and then equilibrated with 3 mL of H2O. After loading the sample, the columns were washed with H2O: MeOH: acetic acid (90:10:0.1 by v/v) to remove impurities, and the lipids were then eluted with 2 times 500 µL of 100% MeOH. Prior to LC-MS/MS analysis, samples were evaporated using a SpeedVac Fand reconstituted in 50 µl of water-acetonitrile-acetic acid (60:40:0.02, v/v/v).

Analysis of lipid mediators by mass spectrometry was performed as described earlier (17), except that the LC/MS-MS system was based on a reversed-phase chromatographic separation (Analysis column: Phenomenex, Kinetex C8, 2.6 µm,150 × 2.1 mm) maintained at 40°C on HPLC (Nexera X2 LC-30AD). The mobile phase consisted of (A) water/formic acid (99.9/0.1, v/v) and (B) acetonitrile. The stepwise gradient conditions were carried out for 10 min as follows: 0–5.0 min, 10–25% of solvent B; 5.0–10 min, 25–35% of solvent B; 10–20 min, 35–75%; 20.0–20.1 min, 75–98%; 20.1–28.0 min, 98%; and finally, 28.0–28.1 min, 10% which was then held for 2.9 min. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min, injection volume was 10 µl, and all samples were kept at 4 °C throughout the analysis.

The HPLC system was coupled to a Shimadzu-8060 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer. The electrospray ionization was mainly conducted in negative mode with the capillary and nozzle voltage set at 4000 V and 1000 V, respectively. Drying and nebulizing gas flow rates were 10 L/min. Interface and desolvation line temperatures were set at 270 °C and 250°C, respectively.

The commercially available version 3 of the LC-MS/MS method package “Lipid Mediators” from Shimadzu was used for simultaneous analysis of lipid mediators. The method contains analytical conditions, i.e., optimized collision energies, dwell times and dynamic MRM transitions, for profiling of 214 lipid mediators, including the 7 deuterium-labelled standards listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Peak integration was performed using the LabSolutions workstation software. Data quality was assessed by calculating the coefficient of variance (CoV) of all analytes in the technical quality control (TQC) pooled lipid extracts, as well as the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R) to determine the linear response curve of TQC serial dilutions. Peak signal-to-noise ratios were determined using the area under the peaks in samples and signal-to-noise ratios of 3:1 and 5:1 were used to set the limits of detection and quantification, respectively. For data normalization, a single point calibration was used, dividing the peak area of the endogenous analytes by the peak area of internal standards in the same group. Representative ion chromatograms for the authentic lipid mediator standards used are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Fig. 12.

Shotgun metagenomic analysis

Microbial genomic DNA was extracted from Cuderm D-Squame skin tapes via a bead beating step on FastPrep-24 Automated Homogeniser (MP Biomedicals), followed by magnetic beads extraction using EZ1 Advanced XL Instrument (Qiagen) with EZ1 DNA Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Firstly, 500 µl of Buffer ATL (Qiagen) was added to each sample and transferred into a Lysing Matrix E tube. Sample tubes were bead-beaten at 4 m/s for 30 s twice. After homogenisation, tubes were centrifuged at maximum speed for 5 min, with 200 µl of the resulting supernatant transferred into 2 ml EZ1 sample tubes (Qiagen). 12 µl of Proteinase K was added to the supernatant, followed by vortexing and incubation at 56 °C for 15 min. Finally, samples were transferred to the EZ1 Advanced XL Instrument (Qiagen) for purification, with a final eluate of 50 µl in buffer EB.

Purified genomic DNA underwent NGS library construction steps using NEBNext® Ultra™ II FS DNA Library Prep Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples added with fragmentation reagents were mixed well and placed in a thermocycler for 10 mins, 37 °C, followed by 30 minutes, 65 °C to complete enzymatic fragmentation. Post fragmentation, adaptor-ligation was performed using Illumina-compatible adaptors, diluted 10-fold as per kit’s recommendations before use. Post-ligation, samples are purified using Ampure XP beads in a 7:10 beads-to-sample volume. Unique barcode indexes were added to each purified sample and amplified for 12 cycles under recommended kit conditions to achieve multiplexing within a batch of samples. Finally, each library sample was assessed for quality based on fragment size and concentration using the Agilent D1000 ScreenTape system. Samples passing this quality control step were adjusted to identical concentrations through dilution and volume-adjusted pooling. Paired-end (2 × 150 base-pairs) sequences were generated from the multiplexed sample pool using the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform, which yielded around 898,525,434 paired reads in total (from three lanes) with an average of 11,980,339 paired reads per library for samples from HELIOS cohort and 536,079,659 paired total reads with an average 6,306,820 paired reads per library for samples from GUSTO Cohort. All sequencing was done in the Novogene sequencing facility per standard Illumina sequencing protocols.

Raw reads were processed using the in-house Nextflow pipeline. First, the raw reads were filtered using FastQC72 (v0.20.0) (default parameters) to remove the low quality bases and adapter sequences. Next, the reads were mapped to human reference hg19 using BWA-MEM73 (v0.7.17-r1188, default parameters) and SAMtools74 (v1.7) to remove human reads. These decontaminated reads which were retained were used for the generation of taxonomic profiles using MetaPhlAn275 (v2.7.7, default parameters). Malassezia species were identified using Pathoscope76.

Quantification of hormonal serum levels

Concentrations of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol (E2) were measured from fasting blood samples, obtained from female HELIOS volunteers, in singletons on the Siemens ADVIA Centaur XPT Immunoassay System (Erlangen, Germany). Daily quality checks were performed, accompanied by calibration every 28, 14 and 21 days for Luteinizing Hormone (LH), Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Estradiol (E2) respectively.

Statistical analyses

Prior to statistical analyses, zero values in all datasets were classified as nil. To determine if lipid mediators differed significantly between HELIOS and GUSTO cohorts, hierarchical clustering was performed by calculating the Euclidean distances followed by clustering using the Ward’s method in MetaboAnalyst. To visualize differences in the skin lipid mediator and microbiome profiles between the HELIOS and GUSTO cohorts, Principal Component Analyses (PCA) were performed using parallel analysis with default setting in GraphPad Prism 10.2.3. For cytokine concentration comparisons between keratinocyte co-cultures and single-culture, a repeated measures Two-Way ANOVA with Geisser-Greenhouse correction and a posthoc Dunnette’s test was performed in GraphPad Prism 9.5.1. To determine the correlations between cytokines and lipid mediators, the Kendall’s Tau b correlation analysis was performed using SciPy 1.8.0. The resultant Kendall’s Tau b correlation p-values were further analysed using the two-stage step-up method of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli at a False Discovery Rate (FDR) of 5% in GraphPad Prism 9.5.1.

Responses