Light sheet illumination in single-molecule localization microscopy for imaging of cellular architectures and molecular dynamics

Introduction

Over the past centuries, optical microscopy has been fundamental for exploring and understanding structural features and sample dynamics. Fluorescence microscopy, developed in the early 20th century, has revolutionized studies of biological samples by enabling the visualization of specific components of interest within the sample in a non-invasive way. However, our ability to resolve cellular structures and molecular dynamics with conventional optical microscopy is bounded by the diffraction limit (DL) of light, which is approximately half of the wavelength of the emission light1,2 and depends on both the wavelength of the light and on the numerical aperture of the objective lens of the microscope. It is thus necessary to overcome the DL in order to study biological phenomena at the nanoscale, which was achieved with the development of super-resolution (SR) microscopy approaches3,4,5,6,7. However, when imaging thick samples, such as mammalian cells and tissues, out-of-focus fluorescence reduces the ability to detect and study specific targets of interest. Light sheet (LS) illumination, a strategy that optically sections the sample by illumination with a sheet of light8, has been demonstrated to improve the performance of fluorescence microscopy by increasing the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) and reducing the photobleaching and photodamage of the sample.

In this review, we discuss various LS microscopy approaches and exemplify their applications in resolving cellular structures and molecular dynamics across different length scales. First, we provide a brief summary of SR techniques for 2D and 3D imaging, with a focus on single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM). We then provide a concise introduction to different LS microscopy geometries and a comparison of their applications in elucidating mechanisms in biology.

Single-molecule localization microscopy

Single-molecule super-resolution imaging and single-particle tracking

Due to the DL of light, it is challenging to resolve structural features smaller than ∼200–250 nm with conventional optical microscopy. Over a decade ago, the advent of SR fluorescence microscopy successfully addressed this challenge. SR imaging, or sub-diffraction limit imaging using fluorescence microscopy, can be achieved using numerous methodologies, all of which allow for the investigation of biological samples at the nanoscale. Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy is one SR imaging approach which works by superimposing a doughnut-shaped depletion laser beam onto a confocal excitation spot3,9, effectively shrinking the size of the fluorescing area beyond the DL. Another method to achieve sub-diffraction limited resolution is structured illumination microscopy (SIM), where the sample is illuminated with known structured patterns of lower spatial frequency and algorithms are used in post-processing to reconstruct the sample features with improved spatial resolution4,10.

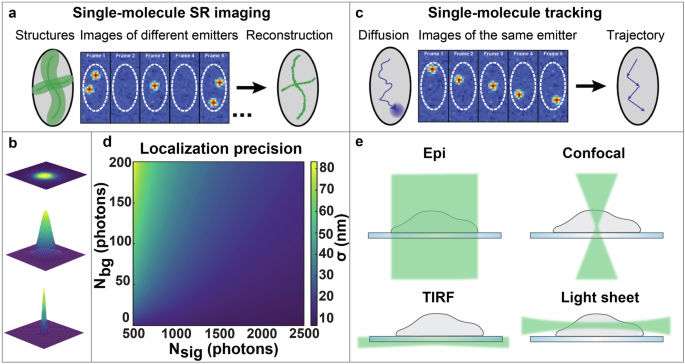

Apart from these deterministic, illumination-based approaches, SR imaging can also be achieved with stochastic, probe-based techniques, in which only a sparse subset of the fluorescent molecules in the sample emits light at any given time. This group of techniques is referred to as SMLM, and includes but is not limited to (fluorescence) photoactivated localization microscopy ((f)PALM)5,6, (direct) stochastic reconstruction microscopy ((d)STORM)7,11, and (DNA-) points accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography ((DNA-)PAINT)12,13. In SMLM, the DL is bypassed by temporally separating the fluorescence from individual fluorophores so that only a sparse subset of fluorophores on a densely labeled structure is imaged in each camera frame. The diffraction-limited intensity distribution detected from each fluorophore, called the point spread function (PSF), is then used to localize the position of each fluorophore in space with a precision far better than the width of the diffraction-limited PSF. This process is then repeated by acquiring many camera frames of different fluorophores to over time build up a SR reconstruction of the underlying structure (Fig. 1a, b)14,15,16.

a The principles of single-molecule super-resolution (SR) imaging. The localization of different emitters over time are used to form a SR reconstruction of the structure. b The principles of super-localization of emitters. The diffraction-limited image of the emitter is acquired, fitted by a model function, and subsequently super-localized. c The principles of single-molecule tracking. The localizations of the same emitter across multiple frames are linked to form a trajectory of the underlying dynamics. d The localization precision σ is shown as a function of signal photons per localization, Nsig, and background photons per pixel, Nbg, based on Eq. (1) using a 110 nm pixel size and 250 nm diffraction-limited spot size. e Comparison of different illumination strategies: wide-field epi-illumination (Epi), confocal illumination, total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) illumination, and light sheet illumination. Figures (a) and (c) are reprinted with permission from von Diezmann, et al. Chem. Rev. 117, 7244–7275 (2017). Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society.

In addition to SR imaging, another major application of SMLM is single-particle tracking (SPT), in which the super-localized positions of each molecule over time can be used to form trajectories that offer information relating to the dynamics and interactions of individual molecules (Fig. 1c)17,18. SPT provides single-particle trajectories with nanoscale resolution, which allows for the study of cellular processes associated with a wide range of molecules, including mRNAs19, membrane proteins20, and macrophage transmembrane receptors21. For examples of reviews focused on the methodology and applications of SPT, please see references15,17,22.

Moreover, multitarget microscopic imaging, most typically achieved via multicolor approaches, is highly desired for studying colocalization of proteins and molecular interactions. With the development of multi- and hyperspectral imaging techniques, the simultaneous detection of fluorescent dyes with different or partially overlapped emission spectra has been enabled23. Advances in hyperspectral imaging include high spectral resolution multi-target imaging with LS illumination24,25,25 and measurements of spectrum-mixed Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) pairs26,27. However, the relatively low spatial resolution and the complexity of assessing chromatic aberrations are limitations of these techniques, which hinder accurate quantitative examination of structures and mechanisms at the nanoscale. Exchange-PAINT is an alternative method which allows for sequential SR imaging of multiple targets using the same fluorophore13,28. This approach mitigates the issue with offsets between channels from chromatic aberrations. However, it comes with the tradeoff of longer acquisition times due to the on/off binding rate of the dye-conjugated imager strands to the docking strands used to label the target of interest and due to sequential imaging of different targets.

The precision by which individual fluorophores can be localized can be estimated by29,30

when using least-squares fitting of the PSF with a 2D Gaussian function, where ({sigma }_{{PSF}}) is the standard deviation of the 2D Gaussian distribution representing the diffraction-limited PSF, (a) is the pixel size, ({N}_{{sig}}) is the number of signal photons detected per localization, and ({N}_{{bg}}) is the number of background photons per pixel (Fig. 1d). As can be seen from Eq. 1, the localization precision in SMLM can be improved by increasing the number of detected signal photons and by reducing the fluorescence background.

Point spread function engineering

Simply localizing a molecule in 2D is often not sufficient to provide a comprehensive understanding of biological morphology and dynamics, especially in thick samples with intricate 3D features. In SMLM, the standard PSF is limited for precise determination of the axial position of molecules, as it is symmetric about the focal plane, changes slowly near its focus, and blurs quickly away from focus15. PSF engineering, in which the shape of the PSF is modulated to encode axial information, represents an effective solution to overcome this challenge, enabling scan-free localization of molecules in 3D. One such engineered PSF is the astigmatic PSF, which can be generated by inserting a cylindrical lens in the emission path to defocus the emitted light asymetrically31. However, the effective axial range of this approach is limited to around 1 µm, making it limited for imaging of thicker samples. A strategy that offers a wider array of PSF options relies on modulating the wavefront of the emission light field in the Fourier plane of the microscope to encode axially varying information. Commonly utilized examples of such engineered PSFs include the double-helix PSF (DH-PSF)32,33,34, which consists of two lobes that rotate around their midpoint when the axial position of the molecule changes, and the Tetrapod PSFs which have been optimized to minimize the theoretical localization precision as quantified by the Cramér-Rao lower bound (CRLB) within the desired axial range up to 20 µm35,36,37. Several other engineered PSFs have been developed for varying axial ranges38,39,40. For a more comprehensive review of PSF engineering, please see reference30.

Illumination strategies for single-molecule localization microscopy

Several different illumination strategies have been developed which offer benefits depending on the sample type and imaging approach. Wide-field epi-illumination is a simple illumination scheme commonly employed in fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1e). Here, the light illuminates the entire sample, including both in-focus and out-of-focus regions. This results in increased fluorescence background which degrades the localization precision in SMLM, as well as increased risk of premature photobleaching and photodamage. These issues are especially problematic when imaging thick samples in 3D. Confocal microscopy is a different illumination strategy that mitigates the effects of background fluorescence by placing a pinhole before the detector to block out-of-focus fluorescence41. However, the high peak intensity in the laser beam focus and the fact that the excitation beam still traverses through the entire thickness of the sample still present challenges such as increased photobleaching and photodamage of the sample. Confocal excitation also requires beam scanning to image an entire field of view (FOV). Alternatively, total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) illumination is an approach that can be achieved by translating a focused beam at the back aperture of the objective lens until the beam reaches the critical angle for total internal reflection of the beam at the coverslip-sample interface. TIRF illumination utilizes the formed evanescent electric field to only excite fluorophores which are close to the coverslip42,43,44, which can drastically reduce the background fluorescence. However, the evanescent electric field is confined to a limited range of approximately a few hundred nanometers near the coverslip before decaying, constraining the applicability of TIRF illumination for imaging in thicker samples.

One alternative strategy that mitigates the previously mentioned issues with fluorescence background, photobleaching, and photodamage while allowing imaging throughout thick samples is LS illumination, where the sample is illuminated and optically sectioned using a thin sheet of light45,46. LS illumination can thus drastically improve conventional fluorescence imaging and offers significant benefits to SMLM. In the subsequent sections of this review, we introduce different implementations of LS illumination for biological imaging at various length scales with emphasis on SMLM (Fig. 2), alongside with its applications in elucidating cellular architecture and molecular dynamics (Fig. 3).

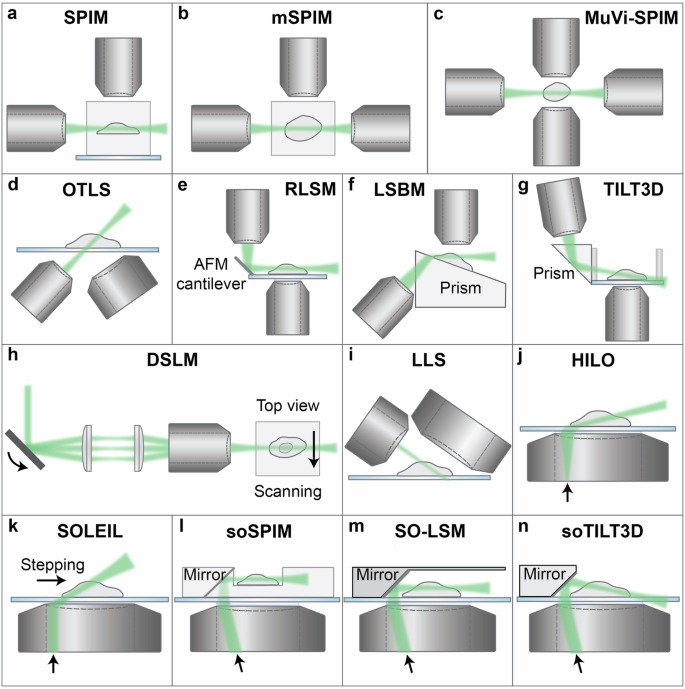

a SPIM: selective plane illumination microscopy8; b mSPIM: multidirectional selective plane illumination microscopy49; c MuVi-SPIM: multiview selective plane illumination microscopy50; d OTLS: open-top light sheet53; e RLSM: reflected light sheet microscopy56; f LSBM: light-sheet Bayesian microscopy58; g TILT3D: tilted light sheet microscopy with 3D PSFs59; h DSLM: digital scanned laser light sheet fluorescence microscopy62; i LLS: lattice light sheet73; j HILO: highly inclined and laminated optical sheet83; k SOLEIL: single-objective lens inclined light sheet localization microscopy87; l soSPIM: single-objective selective plane illumination microscopy102; m SO-LSM: single-objective light-sheet microscopy104; n soTILT3D: single-objective TILT3D107.

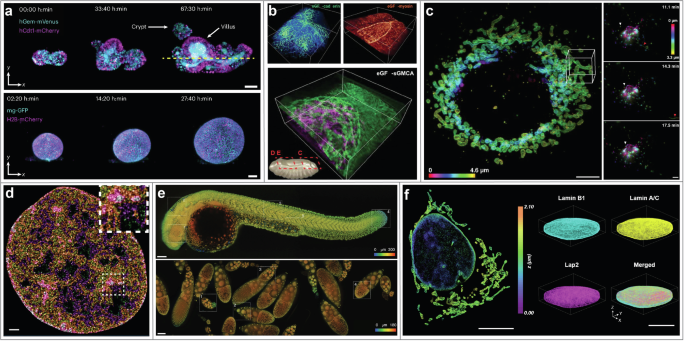

a Time-lapse imaging of multicellular systems with open-top dual-view light-sheet microscope54. Top row: Intestinal organoids expressing the Fucci2-reporter (hGem-mVenus and hCdt1-mCherry). Bottom row: liver organoids expressing mg-GFP and H2B-mCherry. Scale bars: 50 µm. Figure adapted from Moos, F. et al. Nat. Methods 21, 798–803 (2024). Reprinted with permission from Springer, under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. b 3D imaging of embryogenesis dynamics with lattice light sheet (LLS) microscopy73. Top-left: DE-cadherin during dorsal closure in Drosophila development. Top-right: Myosin II during dorsal closure. Bottom row: sGMCA during dorsal closure. Bounding boxes are 86 × 80 × 31 , 80 × 80 × 26 , and 73 × 73 × 26 µm, respectively. From Chen, B.-C. et al. Science 346, 1257998 (2014). Reprinted with permission from AAAS. c Live-cell 3D super-resolution (SR) imaging with LLS microscopy combined with structured illumination10. Left: live-cell 3D SR imaging of mitochondria (Skylan-NS-TOM20) in a COS-7 cell. Right: time-lapse distribution of Golgi-resident enzyme Skylan-NS-Mann II at three exemplary time points in a U-2 OS cell. Scale bars: 5 µm and 3 µm, respectively. From Li, D. et al. Science 349, aab3500 (2015). Reprinted with permission from AAAS. d SR imaging of nucleosomes with HIST microscopy85. Individual nucleosomes are assigned chromatin density classification according to their localizations for study of nucleosome organizations. Scale bar: 1 µm. Figure adapted from Daugird, T. A. et al. Nat. Commun. 15, 4178 (2024). Reprinted with permission from Springer, under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. e 3D high-resolution large-volume imaging with DaXi96. Top row: a zebrafish larva. Bottom row: Drosophila fly egg chambers. Scale bars: 100 µm. Figure adapted from Yang, B. et al. Nat. Methods 19, 461–469 (2022). Reprinted with permission from Springer, under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. f 3D high-density SR imaging of cellular structures with soTILT3D107. Left: 3D reconstruction of lamin A/C and mitochondria (TOMM20) in a U-2 OS cell. Right: 3D multi-target SR reconstruction of an entire cell nucleus labeled for lamin B1, LAP2, and lamin A/C. Scale bars: 10 µm.

Dual- and multi-objective light sheet illumination

LS microscopy has been widely adopted for bioimaging and SMLM due to its optical sectioning capabilities and gentle illumination compared to other illumination methods. Multiple different LS illumination modalities have been designed and implemented to address the specific requirements of various samples. In this section, we review LS illumination strategies that implement two or more objective lenses, organized by the geometry of the optical setup.

Orthogonal geometries

The first instance of LS microscopy was introduced in 1902, in which orthogonal illumination was implemented for imaging of gold nanoparticles45. In 1993, Voie et al. demonstrated the method of orthogonal-plane fluorescence optical sectioning (OPFOS) for imaging of biological samples46. Similarly, the thin light-sheet microscope (TLSM) design was used to study microbes in seawater in a large FOV47. In 2004, Huisken et al. demonstrated a modernized LS illumination design for microscopy, termed selective plane illumination microscopy (SPIM)8. In SPIM, the sample is illuminated from the side with a LS which is generated by focusing a Gaussian laser beam in one dimension using a cylindrical lens, and the emission light is collected by another objective orthogonal to the illumination objective (Fig. 2a). In that work, SPIM was used together with sample rotation to yield multi-view images of structures in Medaka embryos. Combined with PALM and the astigmatic PSF, SPIM was later demonstrated to be suitable for 3D SR imaging of cell spheroids, with a localization precision better than 35 nm48.

However, SPIM presents challenges due to light scattering and shadowing effects from the sample, especially when working with thick samples such as embryos. To circumvent this problem, multidirectional selective plane illumination microscopy (mSPIM)49 and multiview light-sheet microscopy (MuVi-SPIM)50 were demonstrated (Fig. 2b,c). In these systems, an additional detection objective and/or illumination objective is included and orthogonally aligned, which eliminates the necessity for sample rotation when imaging thick samples such as zebrafish and embryos.

Orthogonal arrangement of the illumination and detection objectives poses drawbacks in flexibility of sample thickness due to the limited space restricted by the two objective lenses. Open-top LS microscopes, examples of the V-SPIM designs51,52, eliminate this constraint by arranging the two objectives inverted below the sample, and were demonstrated to enable versatile multi-scale volumetric imaging from organoids up to mesoscale thicknesses (Figs. 2d, 3a)53,54. Another solution to restrictions on sample lateral dimensions is light sheet theta microscopy (LSTM), in which objectives are non-orthogonally arranged to generate two oblique LSs55.

Reflective and refractive geometries

Alternative LS geometries utilize prisms, mirrors, or cantilevers to reflect or refract the LS into the sample plane. In contrast to orthogonal configurations, these geometries are often compatible with standard coverslips, eliminating the requirement for special sample mounts. In 2013, Gebhardt et al. developed reflected light sheet microscopy (RLSM)56, where the LS was generated with a vertically mounted high-NA water-immersion objective and then reflected horizontally by a disposable atomic force microscopy (AFM) cantilever, resulting in a tunable LS thickness down to 0.5 µm (Fig. 2e). With RLSM, the DNA-bound fraction of glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and the residence times on DNA of various oligomerization states and mutants of GR and estrogen receptor-α (ER) were measured, which enabled the determination of different modes of DNA-binding of GR. A subsequent iteration was then demonstrated where the AFM cantilever was replaced by commercially available microprisms attached to coverslips57. However, in both of these designs, the axial slice of about 2 µm closest to the coverslip is inaccessible to the LS, which prevents imaging of structures close to the coverslip.

The limitation imposed by this gap is overcome by light-sheet Bayesian microscopy (LSBM)58, a different LS geometry which utilizes refraction of light. In LSBM, the LS is introduced with a low-NA objective beneath the sample holder and is refracted by a Pellin-Broca prism to redirect it horizontally (Fig. 2f). The horizontal overlap between the LS and the image plane enlarges the FOV while maintaining a high SBR. Combined with a highly efficient Bayesian algorithm for identifying overlapping fluorophores from high-density SMLM, LSBM was first demonstrated for imaging of the distribution and dynamics of heterochromatin protein 1α (HP1α) in human embryonic stem cells58.

A different reflective LS design that allows for imaging all the way down to the coverslip is tilted light sheet microscopy with 3D point spread functions (TILT3D), where the LS is focused by a long working distance objective and reflected by a prism into a glass-walled sample chamber at a tilt relative to the image plane of the detection objective (Fig. 2g)59. Utilizing engineered PSFs, the TILT3D performance was demonstrated by 3D SR imaging of mitochondria (TOM20) and the entire nuclear lamina (lamin B1) in mammalian cells. TILT3D was also used to reveal axial anisotropy in dynamics of chromosomal loci in live in mammalian cells, and to show how both the apparent diffusion coefficient and the anomalous exponent became more isotropic after treatment with latrunculin B18. An improved version of the TILT3D system with a multimodal illumination platform was demonstrated in 2024, which was used to determine the distance between paxillin and actin in mammalian cells60. Lateral interference tilted excitation (LITE) microscopy is a geometry similar to the TILT3D system but without the reflection into the sample. It was demonstrated for time-lapse imaging of organism scale samples, such as C. elegans61.

Scanning geometries

A SPIM-like LS generated with a cylindrical lens has a Gaussian profile along both the width and the thickness of the LS. This characteristic leads to reduced excitation intensity towards the edges of the LS, which can be particularly problematic for imaging of larger-scale samples. To improve the lateral uniformity of the LS illumination, an approach termed digital scanned laser light sheet fluorescence microscopy (DSLM) was developed, where a focused Gaussian laser beam was scanned rapidly to form a virtual sheet of light for illumination (Fig. 2h)62. With DSLM, Keller et al. determined cell nuclei positions and movement in entire zebrafish embryos over time and derived a model of zebrafish germ layer formation62. The axial resolution of DSLM is reported to be 1000 nm, comparable to that of non-scanned SPIM systems designed for imaging mesoscale samples8,55.

However, Gaussian LS beams, such as those used for SPIM and DSLM, suffer from a trade-off between LS thickness, which relates to the optical sectioning ability and axial resolution of conventional LS microscopy, and the confocal parameter, which describes the distance over which the LS thickness remains within a factor of (sqrt{2}) times its beam waist thickness. This tradeoff confines the effective range of the LS along its propagation direction. Unlike Gaussian beams, Bessel beams possess non-diffracting properties, which decouples their central peak thickness from their useful extent along the optical axis63. Additionally, self-healing properties of Bessel beams can reduce beam aberrations and shadowing artifacts that typically arise as the LS propagates through a sample64. In 2011, Planchon et al. demonstrated a method combining scanned Bessel LS illumination with structured illumination and two-photon excitation, resulting in a LS thickness of 0.5 µm and enabling high-speed 3D imaging with isotropic resolution down to 300 nm65,66.

Due to the operation of fast-scanning devices, such as galvanometric mirrors, the scanning mechanism does not limit the imaging speed in DSLM. However, the readout speed of the camera is a factor to consider; for instance, an electron multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) typically takes at least 10 ms for data readout without pixel binning62,67. In 2012, Baumgart et al. employed the idea of confocal line detection by synchronizing the scanning of a Gaussian beam to the rolling shutter detection of a scientific CMOS (sCMOS) camera68. This idea enables an enlarged FOV and higher acquisition speeds and was demonstrated by imaging of polytene chromosomes in C. tentans salivary gland cell nuclei. Dean et al. later adapted this design by utilizing a tunable lens that sinusoidally sweeps a focus along the optical axis to produce pencil-shaped, uniform, focus-extended LSs for illumination69.

While the integrated intensity of non-scanned SPIM and DSLM can be matched within a single camera frame, DSLM illuminates only a single line at any given time, resulting in a higher peak intensity. Consequently, DSLM increases the risk of photodamaging the sample and of photobleaching fluorophores compared to SPIM when used at the same integrated illumination intensity.

In 2015, Dean et al. demonstrated axially swept light sheet microscopy (ASLM)70,71. Instead of scanning a laser spot to generate a virtual LS, a Gaussian LS generated with a cylindrical lens is swept within the FOV and the rolling shutter detection is synchronized with the sweeping of the LS. One early demonstration of ASLM was by volumetric imaging of tractin in MV3 cells within a FOV of 162 × 162 × 100 µm. Recent developments of this geometry include the synchronous collection of the fluorescence signal from both the illumination and detection light paths72.

Lattice light sheet and structured light sheet

Although Bessel LS microscopy mitigates some of the drawbacks of conventional SPIM, the optical sectioning capability of this technique is still inherently limited due to background fluorescence generated by the concentric side lobes of the Bessel beam. To address this challenge, Chen et al. developed lattice light sheet (LLS) microscopy (Fig. 2i)73. The 2D optical lattice utilized in LLS microscopy is generated by the coherent superposition of a linear array of Bessel beams, where proper spacing between the beams leads to destructive interference of the side lobes of the Bessel beams. Analogous to the ideal Bessel beam, an ideal 2D optical lattice is expected to provide an extended applicable FOV. For experimental implementation, the first LLS was generated with a fast-switching spatial light modulator (SLM)73. To enable in vivo imaging, the excitation objective and an orthogonal detection objective were arranged in a geometry with their ends dipped in a shallow media-filled and temperature-controlled bath. In the first demonstration of LLS microscopy, Chen et al. reported for example single-molecule imaging and dynamic studies of microtubules and actin, cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, and embryogenesis in 3D (Fig. 3b)73. In order to provide better imaging applicability, LLS microscopy was later adapted by replacing the SLM with a hard-wired mask74 or dielectric metasurface75 to reduce system complexity and by implementing field synthesis for higher light throughput and simultaneous multicolor illumination76.

LLS microscopy has enabled discoveries critical for improving our understanding of cellular dynamics. Combined with DNA-PAINT, LLS microscopy has been used for 3D single-molecule imaging of whole-cell intracellular membranes, chromosomes during mitosis, and membranes throughout a zebrafish neuromast sensory organ77. LLS microscopy has also been combined with dSTORM, where the distribution of receptors for the neural cell adhesion molecule CD56 throughout the plasma membrane within whole mammalian cells was studied, followed by SPT of CD56 molecules in the plasma membrane of the cells78. Combined with SIM illumination, live-cell 3D SR imaging of mitochondria and of Golgi-resident enzyme Mann II was achieved with LLS microscopy (Fig. 3c)10. Furthermore, by combining LLS microscopy with a 3D-printed microfluidic channel, Zhang et al. broadened the usability of LLS as demonstrated by imaging of MR-1 in S. oneidensis both in cells and in biofilms79. In 2024, Shi et al. developed artificial intelligence (AI)-based LLS microscopy, termed smartLLS80. The AI-assisted control of smartLLS allows for automated FOV selection and data acquisition at significantly higher rates, which enhances the detection of rare events within heterogeneous cell populations.

Single-objective light sheet illumination

Dual- and multi-objective LS illumination strategies have enabled microscopic imaging of diverse and complex biological samples. However, the physical limitations of a dual- or multi-objective configuration typically prevent the use of illumination objectives with a high NA and require constrained sample geometries or sample mounting. To circumvent these limitations, LS illumination with a single objective has been progressively developed and implemented. In the following section, we review various approaches to achieve single-objective LS illumination.

Highly inclined and laminated optical sheet (HILO) microscopy

Early designs of single-objective LS illumination include variable-angle epifluorescence microscopy (VAEM)81,82 and highly inclined and laminated optical sheet (HILO) microscopy83. In these configurations, the excitation beam illuminates the peripheral regions of the back aperture of the objective lens, resulting in an inclined beam in the sample plane that can optically section the sample (Fig. 2j). In the first HILO demonstration, the setup was utilized to unveil the distribution of nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) and to investigate nuclear transport of importin β83. The thickness of the HILO beam can be estimated by

where (theta) is the beam angle and (R) is the size of the illuminated FOV. Equation 2 shows that R must remain relatively small to maintain the LS optical sectioning ability. In order to circumvent this issue, an adapted version termed highly inclined swept illumination (HIST) was developed in 201884. By sweeping the HILO beam and combining it with confocal slit detection, HIST microscopy achieved a FOV of around 130 × 130 µm and was demonstrated for single-molecule RNA-FISH imaging in mammalian cells and mouse brain tissues and for actin imaging in multiple cells within the same FOV. A recent study utilized HIST microscopy for SR imaging of nucleosomes, benefitting from its extended FOV85. Chromatin density classifications were assigned to the localized nucleosomes, and pair correlation functions of the nucleosome organization and the fractal dimension for different chromatin density classes were estimated, revealing that the spatial organization of nucleosome packing is relevant to local chromatin density in the nucleus (Fig. 3d)85.

Oblique plane microscopy (OPM)

HILO microscopy has been shown to effectively improve the SBR due to its optical sectioning capability and it is easy to implement on an epi-fluorescence microscope. However, the resulting LS in HILO microscopy is typically thicker than what can be achieved with other approaches, and the LS thickness, intensity, and depth are coupled. An alternative approach is oblique plane microscopy (OPM), in which the LS illuminates at an angle that is oblique to the optical axis, and the emitted light is re-imaged with an additional lens system in 4f configuration that is aligned to the oblique intermediate image plane86. Furthermore, in an alternative OPM approach termed single-objective lens-inclined light sheet microscopy (SOLEIL), the LS scans through the sample horizontally with a stepping procedure. SOLEIL has been shown to improve the SBR and the achievable localization precision in SMLM compared to epi- and HILO illumination (Fig. 2k)87. Notably, an inclined beam configuration can also benefit confocal microscopy. Dual inclined line-scanning (2iLS) confocal microscopy, where an inclined LS illuminates a relatively large area and scans through the sample, reduces the photobleaching and photodamage associated with traditional confocal microscopy88.

Because the 4f system allows for re-imaging of any plane within the sample, OPM is well-suited for volumetric imaging. Stage-scanning OPM (ssOPM) was demonstrated to allow for 3D time-lapse imaging and spatiotemporal studies of multicellular spheroids expressing a glucose FRET biosensor89. Another OPM platform operating at a more oblique angle, termed single-molecule oblique plane microscopy (obSTORM), demonstrated 3D volumetric SR imaging of tissues and small animals90. A different approach termed swept confocally-aligned planar excitation (SCAPE) microscopy combines oblique LS illumination with a unique scanning-descanning configuration that permits high-speed volumetric imaging and eliminates the necessity of translation and special mounting of samples91. The SCAPE system was developed further into version SCAPE 2.0, which allowed high-speed and high-resolution imaging of neuronal activity throughout C. elegans worm brains, 3D high-throughput imaging of an uncleared, fixed, stained mouse retinal flat mount, and real-time high-speed imaging of a beating zebrafish heart, demonstrating its applicability for high-throughput volumetric imaging92.

Furthermore, Yang et al. developed a single-objective oblique epi-illumination SPIM (eSPIM) system that mitigates the NA reduction of the original OPM design, and conducted parallel volumetric imaging of live mammalian cells in multi-well plates93. Moreover, mesoscopic scale imaging with OPM has been demonstrated94,95. DaXi microscopy, developed by Yang et al., has demonstrated 3D high-resolution large-volume imaging of zebrafish larvae and Drosophila fly egg chambers (Fig. 3e)96. Imaging via rapid scanning has also been demonstrated for in vivo whole organism imaging of the zebrafish vasculature and blood flow dynamics at a high acquisition rate, resulting in a quantitative map of blood flow across the entire organism95. OPM is an actively developing technique that has been shown to be a useful tool for investigating and understanding a large variety of biological samples97,98,99,100,101.

Single-objective selective plane illumination microscopy

In contrast to the comparably complex remote imaging configuration of OPM, single-objective selective plane illumination microscopy (soSPIM) is a strategy that can be implemented on epi-fluorescence setups with conventional detection paths. Demonstrated by Galland et al. in 2015, the key elements of soSPIM are a chip containing 45° micromirrors for reflecting the LS into the sample perpendicular to the optical axis of the detection objective, and beam steering units that enable translation of the LS both laterally and axially (Fig. 2l)102. With this design, Galland et al. demonstrated both 3D single-molecule imaging in cells and larger scale imaging of Drosophila embryos, showcasing the range of samples suitable for soSPIM. Other designs of reflective single-objective LS microscopy include single objective single plane illumination microscopy (SoSPIM) which provides a simplified and affordable fabrication method of polymer-based reflective chips103, single-objective light-sheet microscopy (SO-LSM) that incorporates a reflective side wall into a microfluidic chip to allow for buffer flow during imaging (Fig. 2m)104, and a modality of volumetric LS fluorescence microscopy which combines soSPIM with a multifocus grating and uniform excitation for imaging of single molecules in cell aggregates105.

In 2022, Beghin et al. developed an automated single-objective LS imaging platform for rapid 3D imaging of organoids106. In this work, fabricated pyramidal microcavities that consisted of reflective walls, termed Jewells, were mounted on cell-culture chips, allowing for automatic alignment and calibration of the LS and imaging of multiscale organoids. 3D high-resolution images of various samples ranging from hepato-organoids to intestinal organoids and imaging of dynamic events within neuroectoderm organoids have demonstrated the potential for high-resolution imaging of complex biological samples with the Jewell-assisted system.

However, one common drawback of the above-mentioned single-objective LS approaches is that they are designed for a fixed LS angle parallel to the image plane, which either prevents sectioning of entire, adherent samples all the way down to the coverslip without aberrating the LS or requires the samples to be mounted on raised structures102. This issue was mitigated with the development of the single-objective (so)TILT3D design107 which utilizes a 3D nanoprinted reflective insert in a PDMS microfluidic chip to allow for flexible designs of the chip angle and dimensions and thus a customizable tilt angle of the LS, making the system suitable for imaging of structures ranging from at the coverslip up to larger-scale biological samples (Fig. 2n). Furthermore, a transmissive chip top allows for easy combination with other epi- and transmission imaging modalities. Combined with PSF engineering, a neural network for analysis of overlapping emitters, and active drift stabilization, soTILT3D was shown to enable quantitative 3D whole-cell multi-target single-molecule SR imaging of entire mammalian cells with improved localization precision, accuracy, and acquisition speed (Fig. 3f).

Taken together, single-objective selective plane LS systems allow for imaging samples across various length scales by adjusting the designs of the reflective optics positioned above the objective. They typically offer more compact LS designs compared to dual- and multi-objective systems and remove the issues of steric hindrance and drift that occur in such systems.

Conclusions and outlook

Over the past decades, SMLM has emerged as a powerful approach to further our understanding of cellular nanoscale architecture and molecular dynamics. Combined with LS illumination, the performance of SMLM has been further improved by enhancing the SBR and reducing the sample photobleaching and photodamage. In this review, we have presented various approaches for implementing LS illumination together with discussions on their advantages and limitations, which we hope will guide the researchers in their choice of LS designs. For detailed guidance on the experimental construction of LS microscopy, we recommend recent reviews67,108.

LS microscopy offers potential benefits in multiple research areas. Combining LS microscopy with novel light field modulations can further enhance the imaging performance of fluorescence microscopy109,110,111,112. Using optical elements such as a Powell lens enables the formation of a flat-illumination LS, circumventing limitations of Gaussian-profiled LSs113,114. The generation of LLS73 and other structured LSs115 with modulation devices, such as SLMs, digital micromirror devices (DMDs), and metasurfaces, can improve imaging resolution and enable generation of specific LS characteristics. For scanning geometries of LS microscopy, in addition to the traditional galvanometric mirror scanning approach, a simpler system design can be achieved by generating and scanning the LS with the same DMD116. Implementing adaptive optics (AO) to correct for field-dependent and setup- and sample-induced aberrations both in the excitation and detection paths is another important approach to improve the performance of LS microscopy, especially for large FOV imaging117,118,119.

Furthermore, due to the advantage of reduced fluorescence background, detection and analysis of a broader range of fluorophores with LS microscopy is made possible, which is beneficial for imaging studies that involve samples that are subject to high background120,121.

The capabilities of LS microscopy could be enhanced further through advancements in data acquisition and analysis. Implementation of deep-learning algorithms122,123 for identifying overlapping PSFs allows for denser emitter concentrations, which reduces the data acquisition time. Additionally, AI-assisted fast and automated selection of imaging modes and settings can further improve the speed and efficiency of the data acquisition process80. Overall, LS illumination has proven to be an effective method for improving SMLM to enable and enhance a wide array of imaging and tracking applications.

Responses