Listening to the verses: unveiling phonetic contrasts in Li Bai and Du Fu’s poetry

Introduction

The comparison between Li Bai and Du Fu (hereinafter referred to as Li and Du), two seminal poets in Chinese literary history, has been extensively conducted in scholarly research (Fu 1927; Wang 1928; Wu 1972; Zhou 1975; Yang 2001; Liao 2007; Luo 2019; Hu 2022). Despite the mainstream view of remarkable similarities in their poetic mastery, leading both to be revered as equally great, their stylistic differences are also undeniably felt, contributing to the divergent emotional and perceptual responses from readers. Amidst various interpretations, Li’s poetry is often delineated as embodying a piaoyi (飄逸 ethereal) and haofang (豪放 bold and free) style (Yuan and Luo 2014, p. 230), characterised by elegance and unrestrained expressiveness of emotions. In contrast, Du’s poetry is often associated with a chenyu (沈鬱 profound and contemplative) and duncuo (頓挫 full of twists and turns)Footnote 1 tone (Song 2002; Wang 2009), capturing the layered complexities of life and society and releasing intense emotions in a restrained way. In the comparison of these two styles, readers and researchers tend to focus on the images, themes, or craftsmanship employed in their poems. However, the phonetic aspect, which is less explored, also plays a crucial role in conveying information and evoking emotions and broader psychological responses, thereby helping to shape their poetic styles, as suggested by the principles of sound symbolism.

Sound symbolism, also known as phonetic symbolism or phonosymbolism, is the direct and non-arbitrary association between sound and meaning. The existence of such association has been proven in thousands of languages (Hrushovski 1980; Borroff 1992; Blasi et al. 2016; Svantesson 2017; Joo 2020) and through diverse approaches including case studies (Sato 2004; Smith 2015), corpus-based statistical analyses (Whissell 1999, 2000), as well as surveys and experiments (Sapir 1929; Auracher et al. 2010; Thompson and Estes 2011; Aryani et al. 2016, 2018; Gafni and Tsur 2021). Studies of sound symbolism can serve many purposes, including but not limited to shedding light on the origin of human language—which allegedly challenges Saussure’s notion of arbitrariness of the linguistic sign (de Saussure 2011), aiding in language acquisition by facilitating the association between sounds and meanings (Nygaard et al. 2009), and more practically, promoting commercial success by harnessing the sound effects of brand names (Shrum et al. 2012).

When it comes to literary appreciation, especially the study of poetry, this is the field where sound symbolism is not only felt but also “changes from latent into patent and manifests itself most palpably and intensely” (Jakobson 1987, pp. 87–88). However, despite the central position of sound to “any and all poetry, no other poetic feature is currently as neglected”; even when not neglected, its research is often peripheral (Perloff and Dworkin 2009, Introduction, pp. 1–2). In studies of Chinese poetry, the importance of sound has also been overlooked (Cai 2015, p. 251), with analyses predominantly focusing on how poets select characters, depict scenes, express emotions, or employ literary devices. Research on the phonetic aspect of classical Chinese poetry, however, is much less extensive and usually limited to discussions of pingze (平仄 tonal patterns) and yayun (押韻 rhyming schemes). There is limited exploration of more nuanced sound features—such as voicing, aspiration, coda, and other phonetic elements—and how they contribute to emotional or perceptual effects, an approach that aligns with the principles of sound symbolism. This oversight can be particularly detrimental to the studies of classical Chinese poetry, which was traditionally intended for singing or chanting, making sound an inseparable part of the art form. A conventional way of its composition was that poets, instead of directly writing down what they thought, gave “voice” to their minds and kept deliberating until every single character “sounded” perfect. In this process, whether consciously or not, poets were pursuing the harmony of sounds and taking advantage of sound effects to facilitate the expression of their thoughts and feelings. Thus, neglecting sounds in the study of classical Chinese poetry is a serious lapse and would be detrimental to its interpretation and appreciation.

As masters of words, Li and Du also took advantage of sound effects to enhance the lyrical and artistic qualities of their poetry (Yu 2007, pp. 14–99; Chu 2017, pp. 252–264). By delving into the intricate interplay between sounds and effects within their poetry, we may uncover hidden layers of their artistic expression, thereby unveiling the inner workings of their thoughts and emotions and forming a more comprehensive and objective understanding of their styles. In this consideration, our research seeks to address the following inquiries: Do Li and Du “sound” different? If so, in what ways? What sound features do they prefer respectively and how are these features related or different? How can these features be symbolically interpreted and what are the roles of such symbolic interpretations in enriching the existing knowledge of Li and Du’s styles?

The remainder of this article will be structured into five sections. The “Literature review” section presents a literature review focusing on three areas, namely, sound symbolism, sound and poetry, and Li-Du comparison, aimed at providing a theoretical foundation for the research. The “Data” section describes data collection and processing. The “Methods and results” section introduces the main approaches adopted in this research, including machine learning for sound-based authorship attribution and statistical analyses for extracting prominent sound features and obtaining sound-sentiment relationships, and presents the corresponding results. The “Discussion” section is a detailed comparison of the prominent sound features of Li and Du in terms of emotional and perceptual effects. The “Conclusion” section concludes the research, highlighting its significance and pointing out some limitations.

Literature review

This section reviews literature in three areas, namely, theories of sound symbolism, discussions about sound and poetry, and comparative studies of Li and Du’s poetry.

Sound symbolism

The study of sound symbolism is rooted in the observation that certain sounds or phonetic elements in language can carry inherent meaning or evoke specific sensory or perceptual associations. It has been studied both as a fundamental linguistic issue related to the origin of language and as an important literary aspect concerning the crafts and aesthetics of artistic creation and appreciation.

Sapir (1929) conducted three experiments to show the magnitude symbolism of certain vowels and consonants, using both real and pseudo words and taking the individual differences of subjects into consideration. Drawing upon this work, Newman (1933) introduced dark-versus-bright symbolism, examined the effect of age on symbolic judgement, and explored the correlation between the symbolic scale and mechanical factors such as position of articulation, size of the oral cavity, etc. Köhler (1929; 1947) suggested that readers could readily determine which of a rounded and a spiked shape would be called “baluma” or “maluma”, and which would be “takete”, pointing out the similarity between “properties in vision or touch, and certain sounds or acoustical wholes”, especially in primitive languages (pp. 242–243). This proposition was later known as the bouba/kiki effect (Ramachandran and Hubbard 2001, p. 19). Apart from size, shape, and darkness, Whorf (1956) further incorporated coldness into the symbolic meanings, finding connections between certain vowels and the dark-warm-soft or bright-cold-sharp set.

The association between sound and sentiment, affect, or emotions has also been demonstrated in various studies. Whissell (1999), through statistical comparisons of different texts, found the divergence in phoneme frequencies between texts having distinct emotional effects. He reported the connections between thirty-five phonemes and eight emotional characters including pleasantness, cheerfulness, activation, nastiness, unpleasantness, sadness, passivity, and softness (Whissell 2000). Adelman et al. (2018) conducted a statistical analysis of words from five different languages and identified emotional sound symbolism across all of them. They further found that the initial phoneme of a word plays a significant role in predicting its emotional valence and that phonemes uttered more rapidly are often associated with greater negativity, and suggested that emotional sound symbolism may be an evolutionary adaptation. Uno et al. (2020) discovered that voiced obstruents are associated with negative images, while bilabial consonants may be linked to “baby-ness”. D’Onofrio and Eckert (2021) determined that segmental variations, including vowel quality and stop burst and duration, are associated with affect, influencing listener evaluations through iconic processes akin to those in intonational contours.

Within the ambit of Chinese scholarly discourse, sound symbolism has been a subject of longstanding interest, even though it might not have been explicitly named as such. Guo (1947) deemed that speech originated from imitative and emotive sounds, with the former imitating the objective sounds of the external world and the latter expressing the subjective sounds of internal emotions (p. 8). Similarly, Huang (1964) categorised the origins of speech sounds into two groups—those that convey emotions and those that imitate the shape or sound of objects; taking interjections as an example, he argued that these words, as emotional expressions, resemble laughter, sighs, groans, and shouts, thus showcasing the essence of word pronunciations (pp. 94–95). Huang (1983) compared sounds to the throat of Chinese characters (p. 47), reckoning that whenever the meanings of characters are related, their sounds often tend to be related as well (p. 204). Such sound-meaning connections are referred to as yinjin yitong (音近義通 similar sounds suggest related meanings) in Chinese philology. The initial version of this theory was put forward by Dai Zhen (戴震 1724–1777Footnote 2) as sheng yi tongyuan (聲義同源 sound and meaning originate from the same sources); Zhang Taiyan (章太炎 1869–1936) and Huang Kan (黃侃 1886–1935) elaborated on the essence of this theory and proposed a series of detailed principles to guard against hasty generalisations (Shen and Yang 1991, pp. 339–344). Based on this theory, many scholars connected certain sounds to specific meanings, reflecting the fundamental idea of sound symbolism. For instance, Liu Shipei (劉師培 1884–1919), a master of Confucian classics in the late Qing Dynasty, connected some rhyme categories to meanings like upright, level, expanding, and contracted (Liu 1997, vol. 4, p. 20). This theory has also greatly influenced the interpretation of Chinese literary works, especially those having strong prosodic characteristics, such as poetry.

Sound and poetry

The Russian Formalists in the early 20th century were among the first to systematically and objectively examine the “intrinsic, autonomous meaning” of sounds in poetry (Mandelker 1983, p. 327). Tsur (1992), consulting research from other disciplines to address questions—such as why certain works evoked specific emotional and aesthetic effects—in the literary field, introduced the concept of a “Poetic Mode” of speech perception. Tsur and Gafni (2022) considered that in the poetic mode, listeners attend to some of the pre-categorical sound information and are thus able to assign emotional effects to speech sounds regardless of their semantic meanings.

Empirical studies have endeavoured to unveil this implicit sound-meaning connection in poetry. Whissell (2011a) plotted the emotional sound structure of Paradise Lost based on the use of Pleasant and Passive sounds and accordingly interpreted the long poem as encompassing three narratives. He (Whissell 2011b) also examined Edgar Allan Poe’s strategic use of sounds in poetry to enhance emotional effects in a way that aligns well with his theory about the role of sounds in poetic communication. Kraxenberger et al. (2018) found that the emotional content of poems, pre-classified as joyful or sad, predicts the prosodic features such as pitch and articulation rate, while conversely, joyful and sad prosody affects the emotion ratings of poems, even among non-speakers of the language.

The manipulation of sounds in classical Chinese poetry to achieve aesthetic effects has also been noticed. Lynn (1983), in a comparison of Tang and Song poetry, pointed out that poetry of the Tang era had diao (调 tonality) which allowed it to be sung or even fitted to woodwinds and strings, producing a spreading and lingering effect (p. 160). He also noticed the connection between the sound of poetry and its emotional impact on both poets and readers. Smith (2015), focusing on dieyin ci (疊音詞 the reduplicative vocabulary), presented statistical evidence of the association between sound and meaning in Shijing (詩經 the book of odes). Guo (1947) exemplified how the articulation features of sounds on the one hand depict objective things and on the other express subjective emotions. Yuan (1996) explored the musical aesthetics of classical Chinese poetry by examining its rhythm, tone, and the harmonious interplay between sound and emotion, highlighting the profound impact of poetic sounds, akin to music, on readers’ minds (pp. 95–104). Huang (2009, pp. 155–195) provided a qualitative discussion of diverse sound features in poetry, touching upon rhymes, places of articulation, tones, and sound repetition, as well as their connections with meaning, emotion, and atmosphere.

Although not exhaustively, sound manipulation in the poetry of Li and Du has also been explored. Yu (2007, pp. 14–99), arguing that the prosody of poetry is not merely a combination of sounds but also an integration of meanings, provided an exemplary analysis of rhyming, alliteration, assonance, and reduplication in Du’s poetry, along with their corresponding artistic effects. He noticed that the initial and final sounds, influenced by differences in place and manner of articulation, play a role in conveying various emotions (pp. 48–50). Chu (2017, pp. 6–7) pointed out that Du’s verse line ɡĭu dɑŋ ɣɐp kʰəu kʰĭwok kɔŋ dəuFootnote 3 瞿塘峽口曲江頭 (at the entrance of Qutang Gorge, near the source of Qu River) employs a series of seven plosive consonants to depict treacherous and swift water currents, and Li’s ʑĭaŋ dzuən bɑu ȡĭu sĭĕn 常存抱柱信 (always holding onto the belief of unwavering loyalty) creates a rhythmic effect with opening and closing sounds. Chu (2012) also attempted to analyse finer phonetic features in Du’s poetry, such as the place of articulation, coda, roundness, and tone. However, the study was based on a limited set of examples, making it difficult to generalise the features as truly representative of Du’s style. These studies offer insights into how phonetic elements have contributed to the poetic styles of Li and Du, serving primarily as qualitative and illustrative examples. While they offer valuable perspectives that contribute to a foundational understanding, there remains a strong need for a more extensive and in-depth investigation. An objective analysis that encompasses a broader comparison between the usage of phonetic features in Li and Du’s poetry would refine the nuances of their stylistic differences and deepen our comprehension.

Li-Du comparison

The comparison between the poetry of Li Bai and Du Fu has been an important paradigm in Chinese literary criticism since the Tang dynasty, attributed to two main reasons: first, their works represent the pinnacle of literary creation; second, their works serve as exemplary models for literary study and practice (Liao 2007, pp. 7–9). Given its long history and significance, a substantial body of research has accumulated on this topic. This review focuses on two areas most relevant to the present study for in-depth discussion.

Differences between Li and Du

Differences between Li and Du manifest in various aspects, including their backgrounds and life experiences. However, as this study is centred on textual analysis, this section mainly introduces studies that focus on text-related dimensions, particularly the stylistic features of their works. Broadly speaking, Li is seen as embodying the ideological trend of the High Tang period, characterised by a pursuit of ideals, individuality, and the full expression of personal identity, while Du represents the transitional period later from prosperity to decline, reflecting a focus on the hardships of reality and a shift from individual expression to collective consciousness (Ge 2000, p. 10). While they share a dominant aesthetic of grandeur, their styles differ subtly: Li’s grandeur manifests as heroic and bold, while Du’s reflects a poignant and tragic beauty (p.14). With regard to the philosophical outlook, Li, often referred to as the “Poet Immortal”, was deeply influenced by Daoism (Li 2010, pp. 130–174), as reflected in the themes of freedom and transcendence in his poetry and the spontaneity of his creation. In contrast, Du is known as the “Poet Sage” and “Poet Historian” because of his Confucianist ideals and the documentary nature of his poetry. Nevertheless, Chen (2018, p. 245) argued that Du’s narration is of a micro rather than macro scale and that he did not mean to record facts as a historian but instead incorporated fictive elements, because of which the “history” under his pen is more sympathetic and generous. From the perspective of poetic inheritances, as pointed out by Ge Lifang (葛立方, 1098–1164), though Li and Du were both compared to chejing shou (掣鯨手 whale riders) for their superb command of words, Li’s verses drew heavily from ya (雅 court hymns in Shijing), infusing his poetry with elegance and grandeur, whereas Du’s works were deeply influenced by Li Sao (離騷 encountering sorrows) (Ge 1985, vol. 3, p. 2), imparting a profound melancholic depth to his poetry. In terms of expressive approach and aesthetic effects, Li’s poetry exhibits a vivid and unrestrained beauty, characterised by boldness and passion, explosive bursts of lyricism, and ever-shifting imagination; Du’s sombre and measured style, on the other hand, is achieved through deep, profound, but non-sentimental contemplation, as well as a winding, reflective, and repetitive mode of expression (Luo 2019, pp. 194–234). Li’s genius is marked by a rare, untamed wildness, whereas Du’s talent manifests in a structured and disciplined manner (Yang 2001, p. 59). Emotionally, Li’s poetry is often associated with a more positive tone, while Du’s with a more negative one (Liu 2004, pp. 18–27; Wei 2017, vol. 1, chap. 1).

As for the most appropriate terms to define the styles of Li and Du, this has been a subject of ongoing debate. One of the earliest and most frequently cited assertions comes from Yan Yu 嚴羽 (1191–1241), who adopted a comparative perspective, stating: “Du Fu cannot be as piaoyi (飄逸 ethereal) as Li Bai, and Li Bai cannot be as chenyu (沈鬱 profound and contemplative) as Du Fu” (Yan and Guo 1983). Additionally, Li’s style is often described as haofang (豪放 bold and free) (Yuan and Luo 2014, p. 230) while duncuo (頓挫 full of twists and turns) has been frequently paired with chenyu to characterise Du’s poetic style since the Ming and Qing dynasties (Wu 2007, p. 105). However, the validity of these terms has been challenged. For instance, Zhao (1998) opposed defining Li’s dominant style as haofang, arguing instead that beichuang (悲怆 mournful) more accurately encapsulates his works. Similarly, Kang (2005) criticised the use of piaoyi to describe Li, suggesting that his style varied greatly across different periods. Zhang (2004) contended that applying chenyu duncuo to Du’s works primarily highlights their rich satirical undertones rather than a specific stylistic trait. Furthermore, he noted that the term’s inherent ambiguity has caused confusion and proposed replacing it with alternative expressions. Wu (2007), while acknowledging the multiple connotations and evolving meanings of chenyu duncuo, advocated for a detailed exploration of its layered meanings to better understand Du’s style rather than discarding it. Wang (2009) took a positive and open stance on the evolution of the term, asserting that from the perspectives of both reception history and stylistic development, chenyu duncuo remains a highly appropriate overarching characterisation of Du’s style. Song (2002) supported the use of chenyu duncuo to describe Du’s style but rejected equalling chenyu with depression and melancholy (p. 92).

Given the vast and diverse nature of Li and Du’s poetry corpora, scholars can readily find textual evidence to support contrasting views, which has kept this debate over their stylistic definitions unresolved. However, it is undeniable that Li and Du each possess some distinct, overarching traits that make them representative and iconic figures among all poets of the Tang dynasty. To systematically identify these defining traits, computational methods offer a valuable complement to traditional qualitative analyses. For instance, a corpus-based sentiment analysis can help evaluate whether beichuang truly dominates Li’s style as maintained by Zhao (1998), or whether there is really an underlying melancholy in Du’s poetry. By employing a data-driven approach, this study aims to move beyond subjective interpretations and provide a more concrete and objective understanding of their poetic styles.

The superiority debate

Discussions surrounding Li and Du have evolved from debates about their equal stature to superiority debates, and eventually to analyses of their similarities and differences; throughout this process, the distinctive styles of Li and Du have been established as paradigms of poetic excellence, serving as exemplary models for future generations, representing one of the most important contributions of these discussions (Chen 2019).

The recognition of Li and Du as equally renowned poets was established between 794 and 810 A.D.; during this period, opinions concerning their relative superiority also began to emerge, with Yuan Zhen’s (元稹 779–831) epitaph for Du being one of the earliest recorded instances, where he claimed that Du’s literary achievements surpass those of Li (Chen 2015). After that, the debate continued to gain prominence, further solidifying the discussion on the comparative merits of the two poets, or Li Du youlie lun (李杜優劣論 superiority debate about Li Bai and Du Fu). From the Song and Yuan dynasties onward, the focus gradually shifted to a discussion of their similarities and differences, evolving into one of the enduring controversies in the history of Chinese poetry attracting considerable scholarly attention (Chen 2019, p. 2). For instance, Du was regarded as superior to Li mainly for his moral character, including loyalty to the emperor, love for the country, and compassion for the people, while Li was considered to surpass Du in terms of the stylistic qualities of his works, such as versatility, spontaneity, and evocativeness (Liao 2007, pp. 30–36). Such evaluations are based on individual evaluators’ own perspectives and are prone to subjectivity or even bias. As pointed out by Mo and Zhang (2016, p. 57), poetic standpoints, social ideologies, personal poetic practices, and individual experiences can all influence critics’ perspectives on Li and Du. In this consideration, this study adopts a bottom-up approach, focusing on the works per se by quantifying their features and identifying statistically significant patterns. Building on this foundation, it examines how these quantitative findings relate to existing qualitative interpretations, integrating both perspectives to develop a more comprehensive and objective understanding of their styles.

Data

This research utilised data from three sources: Quan Tang Shi (全唐詩 complete collection of Tang poems, hereinafter QTS), Fine-grained Sentimental Poetry Corpus (FSPC in short) (Chen et al. 2019), and Guangyun (廣韻 extended rhymes). QTS is the source of poems for sound analysis, FSPC is the sentiment corpus for deriving sound-sentiment relationships, and Guangyun is a dictionary to provide the sound information of each Chinese character in the poems.

Poetry corpora

A QTS version in traditional Chinese was adopted to ensure consistency with the Guangyun version available, also in traditional Chinese. The entirety of QTS served as a reference corpus, representing the general condition of Tang poetry. The poems of Li and Du collected therein were extracted to form their respective corpora. Additionally, works of other poets therein were also obtained for comparison as necessary. Poem fragments comprising only one or two verses were excluded, as were duplicates of repetitive poems. In this way, 1006 poems by Li and 1467 by Du were obtained. Only the main body of each poem was included in the corpora, as it was the part embodying the poetic style, while titles, authors, annotations, and other information were excluded.

Sentiment corpus

FSPC was used to infer the sound-sentiment relationships. It contains 5000 Chinese quatrains manually annotated, on both poem and verse levels, as negative, implicit negative, neutral, implicit positive, or positive, with a corresponding score of 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 (Chen et al. 2019, p. 4926). Since FSPC is primarily composed of Tang and Song poems to which the rhyming conventions of Guangyun generally apply, it is assumed that the sound-sentiment relationships inferred from this corpus are largely consistent with those in the poetry corpora under study. We used the OpenCCFootnote 4 tool in Python to convert FSPC from simplified Chinese to traditional Chinese to ensure consistency with Guangyun.

Sound corpus

Guangyun is currently the most suitable rhyme book for Tang poetry studies. Rhyme books were composed in different dynasties to facilitate poetry creation by the literati. Qieyun (切韻 a rhyme book using the fanqie 反切 method, where the pronunciation of a Chinese character is indicated by combining the initial of the first character and the final of the second character) is the earliest extant rhyme book in China. During the Tang dynasty, Qieyun was considered to represent the old standard called Wu (吳 centred around Suzhou to Nanjing) pronunciation, which was gradually replaced by a new standard based on the Chang’an dialect called Qin (秦 centred around modern-day Xi’an) pronunciation (Pulleyblank 1984). Despite that, Qieyun still served as the authoritative source for the pronunciation of literary works in the Tang dynasty. Though Qieyun has been partially lost and its original form is no longer available, its content has been preserved and passed down to the present day in Guangyun, an expanded version compiled in the Song dynasty by Chen Pengnian (陳彭年 961–1017) under the auspices of the Northern Song government, widely regarded as “the most comprehensive and authoritative rhyme book in the Qieyun tradition” (Goh 2015, p. 435). Although Guangyun may not fully capture the actual pronunciations of Tang poetry due to its inherently conflated nature, which smooths out the regional dialect distinctions of the Tang period (Simmons 2023, pp. 123–124), it still largely reflects the general phonetic features of the time and remains a crucial resource for studying the sounds of Tang poetry. In this research, a digital version of Guangyun was obtained from the Yundian Website (韻典網 https://ytenx.org/, hereafter referred to as Yundian) and curated with the printed version Songben Guangyun (宋本廣韻 Song edition of the extended rhymes) (Chen 1982).

In Guangyun, characters having the same pronunciation (initial, final, and tone) form a group headed by a Chinese character named xiaoyun (小韻 small rhyme), and characters with the same nucleus, coda, and tone fall under the same yunmu (韻目 rhyme heading), which is also represented by a Chinese character. Guangyun is organised into different volumes based on the four tones—ping (平 level), shang (上 rising), qu (去 departing), and ru (入 entering), which can be further grouped into two broader categories, namely ping (平 level) for the level tone and ze (仄 oblique) for the other three tones (Shen and Yang 1991, pp. 82–85). Thus, from Guangyun, we directly obtained the following sound features: small rhyme, rhyme heading, four tones, and two tone categories. Researchers deduced the sheng (聲 initial), yun (韻 final), and diao (調 tone) of characters in Guangyun using the fanqie method and further identified key phonetic features such as qingzhuo (清濁 voicing and aspiration), wuyin (五音 five places of articulation), and others, with reference to Yunjing (韻鏡 mirror of rhymes) and related works. These features serve as the foundation for studies on Middle Chinese phonology. Different studies may present minor differences in the classification of specific features. For instance, the qingzhuo classification of the thirty-six initials varies depending on the scheme used. Wang (2014, p. 44) summarised ten different classification schemes, including the one in Yunjing and those by Shen Kuo (沈括 1031–1095), Jiang Yong (江永 1681–1762), etc. Wang (1972, pp. 68–69) noted that for certain initials, such as s 心 and ɕ 审, there is no distinction in terms of aspiration. These initials can be classified as either quanqing (全清 voiceless unaspirated initials) or ciqing (次清 voiceless aspirated initials). In Yinyun Bian Wei (音韻辨微 discerning subtleties in phonology), Jiang Yong classified them as ciqing. We opted for Wang Li’s classification of these sounds into the quanqing category because it is the most common practice across various classification schemes. Other features, including sideng (四等 four grades), erhu (二呼 two articulations), and wuyin, were obtained from Yundian to ensure data consistency.

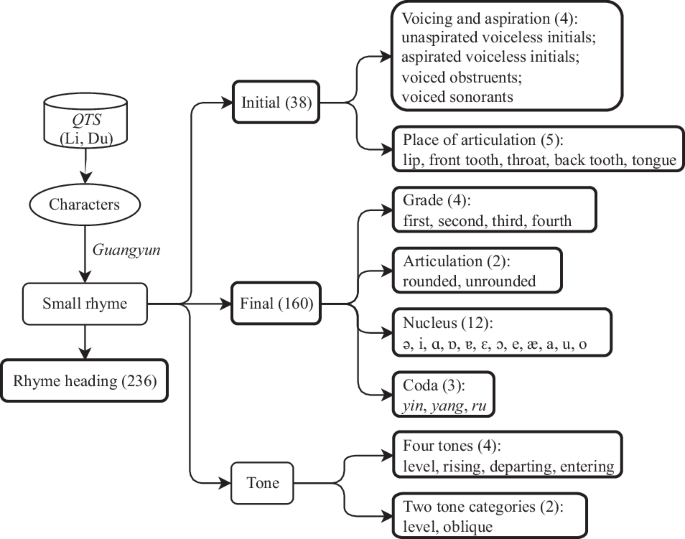

Based on the above sources, the sound information of each character was represented as a series of sound features. Specifically, a character was first mapped to a small rhyme, which was, on the one hand, further assigned to a rhyme heading and, on the other, divided into three parts: initial, final, and tone. The initial was examined from the perspectives of qingzhuo—quanqing, ciqing, quanzhuo (全濁 voiced obstruents), and cizhuo (次濁 voiced sonorants), as well as wuyin—chunyin (脣音 lip sounds), chiyin (齒音 front-tooth sounds), houyin (喉音 throat sounds), yayin (牙音 back-tooth sounds), and sheyin (舌音 tongue sounds). The final was annotated with its grade (first, second, third, or fourth), articulation type (kaikou hu 開口呼, unrounded articulation, or hekou hu 合口呼, rounded articulation), and coda type (yin 陰, no consonant coda; yang 陽, n/m/ŋ coda; ru 入 p/t/k coda) (Zhou 2004). Many phonologists have derived Roman reconstructions for the initials and finals in Guangyun. Our research adopted the reconstruction system in Wang (1984), by virtue of which we singled out the nucleus in each final, the main vowel determining its major phonetic qualities.

The sound feature extraction process described above is illustrated in Fig. 1, where the bolded boxes indicate eleven groups of features used in constructing the sound vectors, and parentheses show the number of variant elements in each group. Taking the box “Initials (38)” as an example, this division contains 38 sound features, including p 幫Footnote 5, pʰ 滂, b 並, m 明, … ɣ 云, j 以, l 來, ȵʑ 日, which will form 38 dimensions of the sound vector representing a character. Following this process, a sound corpus was constructed, encompassing 470 sound features for each character in Guangyun. This sound information was then utilised for sound vector construction and sound frequency calculation, as detailed in the “Methods and results” section.

It presents the process of obtaining the sound information (including 470 sound features) for each character in QTS (including the poems of Li and Du).

It should be noted that polyphones were not specifically addressed in the above process for several reasons. First, the disambiguation of polyphones remains a great challenge in grapheme-to-phoneme conversion. While models have been developed to convert Chinese texts into Putonghua speech (Sui et al. 1998; Zhang 2021; Zhang et al. 2022), little research has focused on using traditional phonetic materials, such as rhyme books, for polyphone disambiguation in classical Chinese texts. Second, Guangyun’s unique annotation system makes it difficult to determine the precise pronunciations and meanings of each polyphone character, posing challenges in obtaining high-quality labelled data for training automated models in polyphone disambiguation. Despite that, our authorship attribution models relying solely on phonetic features achieved F1 scores as high as 83% (see the “Machine learning” section for details), confirming the effectiveness of the phonetic annotation scheme for the current research. It is also worth noting that even lexicon- and semantics-based models encounter inaccuracies due to issues such as word segmentation errors and inherent limitations in vectorisation mechanisms. In this context, our models achieve strong performance in Li-Du comparison, providing reliable results that contribute to more nuanced research in the future.

Methods and results

In this research, both machine learning and statistical analysis were employed for a comprehensive sound-based comparison of Li and Du’s poetry. Machine learning was used for poem classification based on sound features, while statistical analysis was conducted on the Li and Du poetry corpora, as well as the sentiment corpus FSPC.

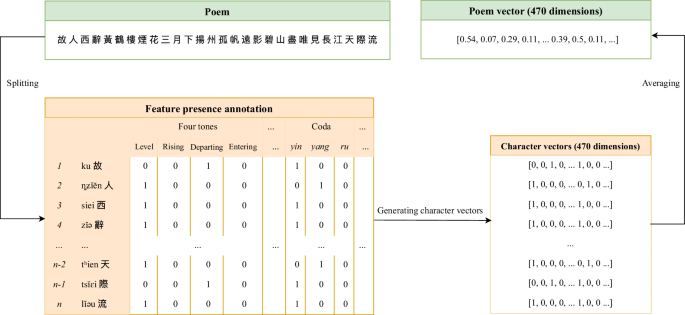

Machine learning

First, we leveraged the sound corpus to convert each character in the poems of Li and Du into a 470-dimensional one-hot encoded vector, where each dimension represents a distinct sound feature. A value of “1” is assigned if the character exhibits the feature; otherwise, a “0” is assigned. This method ensures an explicit and unambiguous encoding of sound characteristics for each character. Instead of examining the sequences of character sounds in poems, our focus was primarily on quantifying the aggregate presence of sounds within a poem. For each poem, the character sound vectors were summed elementwise across all dimensions and then normalised by the total character count, yielding a 470-dimensional vector where each dimension represents the normalised frequency of its corresponding sound feature. Figure 2 is an exemplary illustration of the poem vector generation process.

It presents the process of obtaining a 470-dimensional sound vector for a poem.

To identify the most effective sound-based classification model for Li and Du’s poetry, we experimented with a diverse range of machine learning algorithms to evaluate their pattern recognition capabilities. We tested several traditional models from the scikit-learn library (Pedregosa et al. 2011), including Random Forest (RF), Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Naive Bayes (NB), and K-nearest neighbours (KNN). They were selected for their proven efficacy in text classification tasks, each bringing a unique approach to the handling of feature spaces and decision boundaries. Additionally, we tested neural network-based models with their base configurations, including Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) from scikit-learn, as well as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks using TensorFlow’s KerasFootnote 6 API. They were adopted for their capacity to capture hierarchical feature interactions. Considering the imbalanced nature of the data composed of different numbers of Li’s and Du’s poems (1006 and 1467 respectively), we used stratified 10-fold cross-validation in training and testing the models. The average performance of each model is presented in Table 1.

As evident, several of the models demonstrated strong performance, with the highest achieving an average weighted F1 score of 83.7%, indicating the effectiveness of sound features in differentiating between Li and Du. Yi et al. (2007), using Bag of Words (BOW) for poem representation and a basic NB model, only achieved an accuracy of 73.5 in Li-Du classification before any model improvement. Zhou et al. (2022), using word vector representations derived from Word2Vec and BERT, achieved an F1 score of 88.37 with NB and 86.42 with SVM in discerning between Du and Bai Juyi (白居易, 772–846). That is, with the same fundamental configurations for NB or SVM, sound features can achieve a performance comparable to those of lexical (BOW) and semantic (Word2Vec + BERT) features in authorship attribution. This suggests the necessity of including phonetic features in an objective and comprehensive comparison of poetic styles, especially in Li-Du comparison.

Statistical testing

To delve into the Li-Du sound difference, we conducted chi-square tests to extract the prominent sound features from their respective corpora. To further understand the implications of these features, including their emotional effects, we conducted Spearman’s rank correlation tests on the sentiment scores and sound frequencies of poems in the sentiment corpus.

Chi-square test

The goodness of fit chi-square test is a statistical method to determine how well observed data fit an expected distribution. It is particularly useful for analysing categorical data and testing hypotheses about frequency distributions across different categories. It can be used to determine whether differential usage is due to chance factors or not (Whissell 1999, p. 26). Specifically, in our research, chi-square tests were used to identify the significantly overused sound features in the poetry corpora of Li and Du.

We first generated the respective character count lists for the Li and Du corpora and then computed their sound statistics based on each character’s phonetic information from the sound corpus. Next, we conducted individual chi-square tests for each of the 470 sound features in the Li and Du corpora. In each test, the observed counts of a given sound feature were compared against the total character counts in the corpora to derive the expected counts. The null hypothesis for each test posited that the counts of the examined sound feature in the Li and Du corpora were independent of the poet, indicating no significant difference in its usage between the two corpora. The alpha value was set at 0.05. If the calculated p-value was smaller than 0.05, the null hypothesis was rejected; otherwise, it was accepted. Among the significant results, if the observed count of a feature in the Li or Du corpus was larger than its expected one, the feature was identified as overused in that corpus. This process allowed us to identify the sound features overused by each poet, which could also be described as their favoured, preferred, representative, prominent, or distinguishing features (see Table 2).

Table 2 presents Li and Du’s preferred sound features in eleven groups. In “Initial”, “Final”, and “Rhyme heading”, both poets possess a variety of distinguishing sound features. However, determining the overall effects of these diverse features is challenging due to the mixed symbolic meanings thereof. Given this complexity, in subsequent sections, we would refrain from exploring these groups but focus on the eight more discernible ones, namely “Voicing and aspiration”, “Place of articulation”, “Grade”, “Articulation”, “Nucleus”, “Coda”, “Four tones”, and “Two tone categories”. These groups, comprising fewer components and being more interpretable, facilitate a clearer and more intuitive understanding of the overarching patterns in Li and Du’s poetry.

Spearman’s rank correlation test

To interpret the representative sound features of Li and Du, it is crucial to first determine their different symbolic effects, among which the emotional effect is a major one. We utilised the same method as described in the “Machine learning” section to convert each poem in the sentiment corpus FSPC into a vector of normalised sound frequencies. Given the nature of our data, where the normalised sound frequencies are real numbers in the range (0, 1) and the sentiment scores are discrete integers ranging from 1 to 5, we selected Spearman’s rho, a non-parametric rank correlation measure, for its ability to handle ordinal data and its robustness to non-linear relationships and non-normal distributions. We conducted Spearman’s rho correlation analysis between the sentiment scores and the normalised frequencies of each sound feature in the eight groups across the 5000 poems in FSPC.

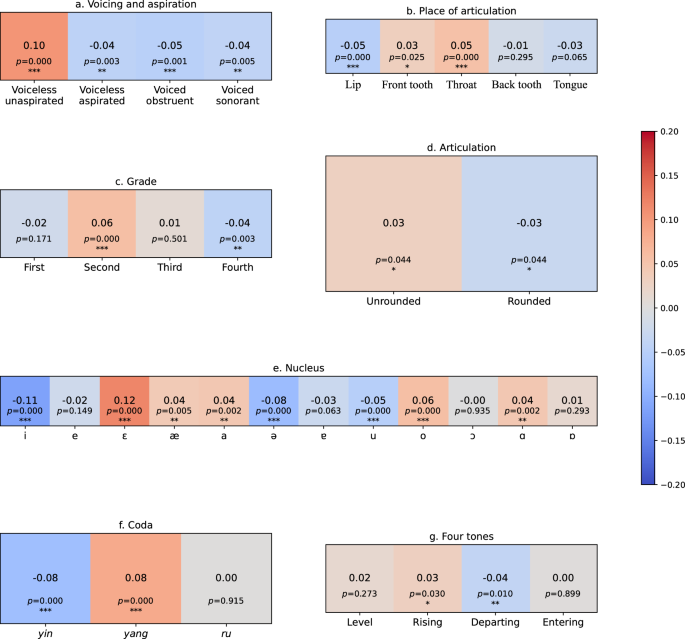

In this way, we quantified the monotonic relationship between the presence of a specific sound feature and a poem’s sentiment score. A positive Spearman’s rho suggests that an increase in the feature frequency correlates with a higher sentiment score, indicating a tendency towards greater positivity. Conversely, a negative Spearman’s rho suggests the opposite. The statistical significance of the observed correlations is assessed using p-values, with values below the conventional alpha level of 0.05 considered significant. The results are detailed in Fig. 3Footnote 7, which includes seven heatmaps, each representing a group of features. The “Two tone categories” group was excluded due to the absence of significant correlations.

It presents the statistical analysis results showing the correlation of sound features with position or negative sentiment. a Voicing and aspiration: Voiceless unaspirated → positive; the others → negative. b Place of articulation: Front tooth and throat → positive; lip → negative. c Grade: Second → positive; fourth → negative. d Articulation: Unrounded → positive; rounded → negative. e Nucleus: ɛ, æ, a, o, and ɑ → positive; i, ə, and u → negative. f Coda: yang → positive; yin → negative. g Four tones: Rising → positive; departing → negative.

In each heatmap, half or more of the features exhibit a significant correlation with sentiment. For example, among the three coda types in Fig. 3f, the yin (陰) and yang (陽) codas show a significant correlation with negative and positive sentiment, respectively. Similarly, the rising and departing tones in Fig. 3g correlate with positivity and negativity, respectively. These statistical correlations highlight the potential of certain sound features to influence how sentiment is perceived in texts. Accordingly, sound features can be categorised as positive or negative based on their association with sentiment. A poet who predominantly employs positive sound features is likely to elicit more positive emotions in readers compared to one who favours negative sound features. This observation provides a critical foundation for interpreting the sound differences between Li and Du from the perspective of sentiment or emotions, which will be discussed in detail in the “Emotional tendencies conveyed by sound” section.

Discussions

The distinct sound features preferred by Li and Du evoke emotional responses, which can be detected through sentiment analysis, as well as perceptual effects that, while subtler than explicit semantic meanings, remain discernible through the articulatory and acoustic characteristics of the sounds themselves. Our ensuing discussions will incorporate both emotional and perceptual effects to appreciate the multifaceted ways in which sound contributes to the poetic experience.

Emotional tendencies conveyed by sound

Extensive research on the relationship between sound and emotion has produced diverse and sometimes contradictory findings (Whissell 2000, 2011a; Auracher et al. 2010; Kraxenberger et al. 2018; Tsur and Gafni 2022), many of which may not be directly applicable to Tang poetry. We therefore avoided relying on any single study for deducing sound-emotion relationships. Instead, we adopted a data-driven approach, drawing on statistical associations identified within the sentiment corpus FSPC composed of annotated Chinese quatrains to explore sound-emotion interactions in this specific context.

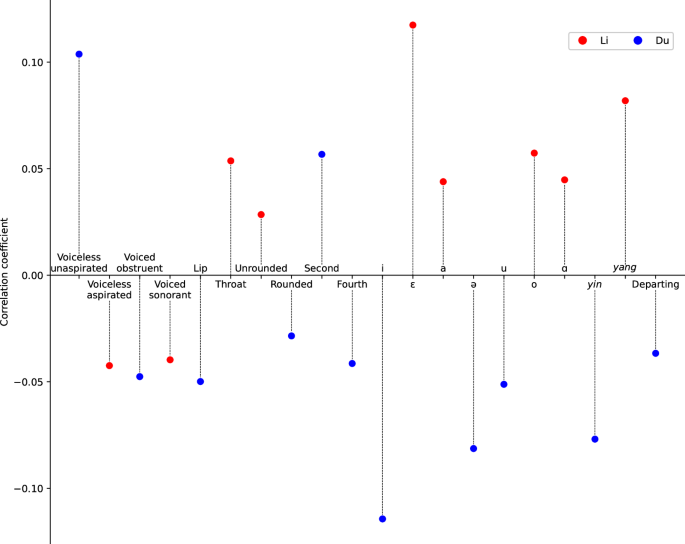

As detailed in the “Spearman’s rank correlation test” section, a set of phonetic features was found to correlate with positive sentiment, while another set correlated with negative sentiment. These features were mapped onto a coordinate system, as illustrated in Fig. 4. In this system, the x-axis represents the feature names, and the y-axis represents the sentiment correlation coefficients. Each feature is represented by a dot, with those favoured by Li marked in red and those preferred by Du in blue. Positive and negative correlation coefficient values signify correlations with positive and negative sentiment, respectively.

It maps Li and Du’s preferred sound features onto a coordinate system where the x-axis lists the sound features, and the y-axis indicates the direction and strength of their correlation with sentiment. Red and blue dots represent features favoured by Li and Du, respectively.

Figure 4 shows Li and Du’s inclinations towards positive and negative sound features, respectively, as indicated by most red dots above the x-axis and most blue ones below it. This suggests that Li’s preferred phonetic elements are more likely to evoke a sense of elevated mood or positivity in readers while Du’s tend to contribute to a more sombre or melancholic atmosphere in his works. This difference in emotional tendencies has been widely identified in previous literary analyses as an integral part of the poetic styles of the two poets. It does not mean that each poet focused on a single theme or conveyed only one type of emotion. For instance, Du displays a preference for voiceless unaspirated initials and second-grade finals, both associated with a positive sentiment, and Li favours voiceless aspirated initials and voiced sonorants, which are linked to negative emotion, implying that their emotional expressions are far from unidimensional. Nevertheless, there is reason to assume that their general expressive tendencies have resulted in distinct emotional experiences for their readers. As observed by Luo (2019, pp. 197–198), when writing on the same themes as other poets, Li often expressed a different emotional tone. For example, Luo noted that Li’s poems on Taoism and the pursuit of immortality do not reflect the usual detachment from worldly matters but instead exude a passionate, open-hearted embrace of life. Luo further pointed out that even when writing about indulgence in wine and revelry, Li’s tone remains vibrant and uplifting, in contrast to the melancholic or decadent tone often found in the works of literati in a declining empire. On the other hand, Du’s emotional tone is shaped by deep concerns and reflections stirred by the chaos of warfare, contributing to his well-known sombre and melancholy style (Luo 2019, pp. 216–218). Despite the negativity surrounding his depiction of the country’s disasters and the suffering of its people, as well as his own misfortunes and tragic life, Du never lost his political enthusiasm and was never fully demoralised or overwhelmed by despair (Feng 1999, pp. 172–173). Therefore, instead of pessimistic or dispirited complaints, we sense more of the depth of his thoughts and the breadth of his inner world (Luo 2019, pp. 227–231).

That is, our findings based on sound data not only align with traditional qualitative interpretations but also provide a more objective foundation for further exploration, demonstrating that the perceived emotional differences between Li and Du reflect tendencies rather than absolutes. This approach deepens our understanding of the rich connotations and subtle intricacies within their works, offering both concrete evidence and a fresh perspective. While the emotional tendencies embedded in Li and Du’s sound features are observed at the corpus level as a general tendency, a deeper analysis of select cases can provide clearer insights into how these sounds contribute to the overall emotional tone in their poetry. Taking the yin (陰) and yang (陽) features as an example, Li is characterised by the positive yang and Du by the negative yin, as shown in Fig. 4. A yang final ends with one of the nasals n, m, and ŋ, which, due to their smoother and more resonant quality, can contribute to a softer, more continuous sound, particularly when at the end of a syllable, potentially adding a sense of ease. While this quality doesn’t necessarily lead to a positive sentiment, it may subtly reinforce a positive emotional undertone. Similar effects can also be observed in modern Chinese. For instance, Wang (2022) reported that in children’s literature, nasals appear more frequently in the names of positive characters than in other names. Li and Jiang (2024) found that, compared to diphthongs without nasal codas, those with alveolar nasals are statistically politer and friendlier, while those with velar nasals are also statistically politer. On the other hand, a yin final ends in a vowel rather than a consonant, tending to have an open quality. Unlike the more definite closure of nasal codas, the open-ended vowel may evoke a sense of incompletion or unresolved thoughts. This unresolved nature, though not dictating the mood, might subtly reinforce the introspective quality often accompanied by negative sentiment, as in Du’s poetry.

Another example is Du’s preference for the negative departing tone, as shown in Fig. 4. The negative sentiment associated with this tone, as identified from the sentiment corpus FSPC, aligns with the melancholic undertone of Du’s poetry, which frequently depicts the suffering of the people and his own desolate wandering in a corrupt and declining empire. This marked consistency is far from coincidental; rather, it suggests that sound preference is closely related to the poet’s poetic style and plays a role in shaping the aesthetic experience of readers. This data-driven approach demonstrates the potential influence of sound on the poetic styles of Li and Du, an aspect often overlooked in past discourse mostly due to methodological limitations.

Perceptual effects of sound properties

Emotional impact is merely one of many effects of sound. Despite Li and Du’s general tendencies towards two sentiment polarities, their preferred sound features do not strictly fall under these two categories. For instance, Fig. 3a shows that in terms of voicing and aspiration, Du favours both positive voiceless unaspirated initials and negative voiced obstruents, while Li’s preferred sound features in this aspect are both negative, suggesting that sentiment-based analysis alone may not fully account for the role of sound in their poetry. Given these complexities, adopting another perspective by examining the perceptual effects of sound properties may offer a more detailed and nuanced analysis, enriching our understanding of poetry’s many effects beyond sentiment alone.

Tsur (1992) noted that in the poetic mode, pre-categorical sensory information underlying speech sounds could reach consciousness, allowing certain speech sounds to be associated with specific perceptual qualities (p. 28). He further argued that both acoustic information and articulatory gestures are key to understanding the emotional and perceptual qualities of speech sounds (p. 47). Many experiments also indicated that the symbolic meanings of phonetic sounds might be based on their objective properties (Newman 1933, p. 69). Given this background, this section presents a comparative analysis of the perceptual effects of Li and Du’s prominent sound features based on their articulatory and acoustic characteristics to further understand their divergent poetic styles. To illustrate these effects, we selected exemplar verses from the corpora through a three-step process. That is, when examining a sound feature, we first calculated its relative frequency in each verse. For example, in a seven-character verse, if two characters carry the level tone while the others have rising, departing, or entering tones, the relative frequency of the level tone in this verse would be 2/7. Next, we ranked the verses in descending order based on the relative frequency of the feature under examination. Finally, from the top-ranked verses, we selected those easier to interpret than others, ensuring that readers could quickly grasp their meanings and readily recognise the connection between the sound feature and its effect. The eight groups of preferred sound features identified in the “Chi-square test” section are categorised into the following three sections based on their associations with initials, finals, or tones and analysed separatelyFootnote 8.

Initial (sheng 聲)

In the context of Middle Chinese, initials are the consonantal sounds that occur at the beginning of a syllable. Their objective properties include voicing and aspiration, as well as place of articulation. This section examines how these properties contribute to the poetic styles of Li and Du.

Voicing and aspiration (qingzhuo 清濁)

In this aspect, Li favours voiceless aspirated initials and voiced sonorants, while Du prefers voiceless unaspirated initials and voiced obstruents.

(1) Li’s voiceless aspirated initials versus Du’s voiceless unaspirated initials

The symbolic effects of phonemes may arise from the shared properties of their sounds and the stimuli they represent. These shared properties can be perceptual, conceptual, affective, or linguistic (Sidhu and Pexman 2018). The voiceless aspirated initials preferred by Li are typically articulated with a noticeable exhalation, as the breath is forcefully expelled through the mouth. Thus, they possess a perceptual quality of airflow, which may evoke the sensation of blowing wind or air release. This sound-stimuli relationship is particularly evident in Chinese characters tɕʰǐwe 吹 (to blow), tʰɑn 嘆 (to sigh), and tɕʰĭə 嗤 (to sneer at), all of which feature a voiceless aspirated initial, demonstrating a strong connection between their phonetic properties and meanings. While these characters directly relate to airflow, the symbolic effects of voiceless aspirated initials extend beyond this concrete meaning. As Sidhu and Pexman (2018) suggest, crossmodal correspondences can arise through transitivity, where phonemes are directly linked to certain stimulus dimensions, which in turn mediate associations with other related properties, often through shared effects on a person’s level of arousal or affect rather than purely conceptual connections. In this way, aspiration can metaphorically represent the release of strong emotions—akin to the forceful expulsion of air—particularly those that were previously constrained. This phonetic feature thus conveys power, urgency, and emphasis, evoking a heightened emotional response in readers and listeners. In expressions like tsʰiei tsʰĭɛŋ 淒清 (desolate and bleak), kʰɑŋ kʰɑi 慷慨 (spirited), and tʃʰĭək tʃʰĭaŋ 惻愴 (grieving), aspiration plays an important role in enhancing the conveyance of feelings. Li’s preference for voiceless aspirated initials not only supports his unrestrained expression of intense emotions but also effectively evokes similar emotional responses in his recipients. Taking his couplet dʒĭəu tsɑk tsʰĭəu pʰu kʰɐk ɡĭaŋ kʰɑn tsʰĭəu pʰu xwa 愁作秋浦客, 強看秋浦花 (As a sorrowful sojourner in Qiupu, I must summon energy just to appreciate its flowers.) as an example, it contains a series of six aspirated initials tsʰ, pʰ, kʰ, kʰ, tsʰ, and pʰ, creating a continuous airflow that resembles a long sigh. When hearing or reciting the verse, appreciators can sense both the physical act of sighing (perceptual properties) and the abstract release of emotion (affective properties), which adds to the sorrowful feeling expressed.

The voiceless unaspirated initials favoured by Du, being muted compared to their voiced counterparts and unlike the aspirated ones that may evoke excitement or dynamism, are softer and subtler, and offer crispness and clarity, evoking a sense of precision and deliberation. For example, Du uses a succession of voiceless unaspirated consonants ʃ, x, s, p, ɕ, t, k, and p in the couplet ʃæn xwa sĭaŋ –Footnote 9ĭɐŋ pĭwɐt ɕwi tieu dzi ku pĭwəi 山花相映發, 水鳥自孤飛 (Mountain flowers bloom in mutual complement, while a water bird flies in sheer solitude.) to imply his complex feelings—joy for a friend’s return to the imperial court and sadness at being left alone—in a controlled, implicit, and well-designed way. In the depiction of pains and sorrows caused by wars, Du’s couplet sĭɛk kĭwəi sĭaŋ ɕĭək ɕĭɛu tsɑu jĭə tɕĭɛn ȶĭaŋ tɑ 昔歸相識少, 早已戰場多 (When I returned in the past, there were already few familiar faces; by now, the place has long been a frequent battlefield …) does not state explicitly but instead implies that even fewer of his acquaintances remain due to continuous warfare. This deep speculation and profound emotion, conveyed in a highly constrained manner, are accentuated by the repeated use of voiceless unaspirated initials s, k, s, ɕ, ɕ, ts, tɕ, ȶ, and t, resembling a calm surface concealing a turbulent undercurrent.

(2) Li’s voiced sonorants versus Du’s voiced obstruents

Voiced sonorants, such as nasals, liquids, and glides, are speech sounds produced with a relatively open passage for airflow, as opposed to voiced obstruents characterised by more restricted airflow. They are more enduring and resounding, allowing them to contribute to the musicality and harmony of poems. For instance, in Li’s couplet ȵʑĭə ŋɑ jwi ɣĭəu ləu jĭo kĭuən jĭwoŋ mĭu pĭwaŋ 而我遺有漏, 與君用無方 (I cast aside the mortal world and join you in this infinity.), a dense use of voiced sonorant initials ȵʑ, ŋ, j, ɣ, l, j, j, and m creates a sense of fluidity and resonance, aligning with the harmonious state in Li’s pursuit of Daoist ideals. Besides, the initials m, ȵʑ, ŋ, m, ȵʑ, l, and l in his couplet mi ȵʑĭĕn pĭuət ŋɑ ɡĭə tsʰɑu muk ȵʑĭĕt lieŋ lɑk 美人不我期, 草木日零落 (The beauty no longer awaits me, as grasses and trees wither day by day.), melodious and lingering, add to the lyricism of his poetry. The alliteration created by the repeated liquid l at the end of the couplet is particularly impressive, producing a reverberation effect that amplifies the affective tone of the verses.

Du’s use of voiced obstruents, including stops, fricatives, and affricates, adds a layer of tension, introspection, and constraint to his poetry, not only enhancing his complex and profound themes, often centred on social and personal hardships, but also contributing to his signature tone characterised by solemnness and sombreness. Recalling and lamenting the good old days that were gone and would never return, Du arranged nine obstruents ɡ, ȡ, z, ʑ, dz, d, dz, ɡ, and d in the couplet ɡǐe ɣĭwaŋ ȡɐk lĭə zĭĕm ʑĭaŋ kien dzuɒi kĭəu dɑŋ dzien ɡĭəi dɑk mĭuən 歧王宅裏尋常見, 崔九堂前幾度聞 (I met you frequently in the mansion of Prince Qi and heard you sing several times in the hall of Cui Jiu.). The repeated obstruction of airflow reflects the struggle to reconcile the joy of reuniting with an old friend in a distant land with the sorrow of shared hardship and the suffering of their displaced people.

To conclude, the contrasts in voicing and aspiration between Li and Du serve as an acoustic representation of their differing thematic concerns and even personalities, helping to shape a Li Bai who is passionate, expressive, and keenly pursuing harmony and elegance, and a Du Fu who, while equally emotional, is more restrained and contemplative.

Place of articulation (wuyin 五音)

In terms of the articulation places of initials, Li’s poetry exhibits a preference for throat sounds, articulated at the rear of the vocal tract, whereas Du favours lip sounds, produced with the lips at the very front of the vocal tract. Throat sounds are typically perceived as deep and heavy, dignified and magnificent, while lip sounds are wide and pure, dull and distant (Zhou 2021, p. 54). The different effects of these two groups of initials perfectly match the known styles of Li and Du.

Specifically, throat sounds concern airflow at the throat, resembling the quick intake of breath or gasp that people commonly make when startled or amazed, as in the exclamation -ɐi ɣĭu xǐe 噫吁戲 (Alas!) in Li’s famous Shu dao nan 蜀道難 (Difficult is the road of Shu). Meanwhile, throat sounds are deep and resonant. Taking x, ɣ, x, ɣ, ɣ, –, x, and j in Li’s couplet xǐe ɣuɑ xǐe ɣuɑ ȵʑĭo ɣiei kuət muət -u xuɑŋ jĭĕm tɕĭə puɑ 羲和羲和, 汝奚汩沒於荒淫之波? (Xihe, Xihe, why were you immersed in the boundless sea?) for example, they can create a sense of intensity and emotional weight, which aligns with the powerful imagery in the couplet and exudes tremendous strength and ambition.

On the other hand, lip sounds are produced at the front of the mouth, with the lips either coming together or closely approaching each other, creating a sense of closure and restraint. In Du’s verse pʰĭɛu pʰĭɛu bĭwɐm pɐk man 飄飄犯百蠻 (drifting through the wilderness of many barbarians), each of the five syllables begins with a lip sound pʰ, pʰ, b, p, or m. The physical closeness in the articulation of these sounds contributes to the constrained emotional expression characterising Du’s poetry. Meanwhile, the continuous motion of the lips during the articulation mirrors a drifting movement, symbolic of Du’s wandering life during times of war. The variation among the five labial sounds, with their diverse characteristics in voicing, aspiration, and nasality, evokes a sense of fluctuation, resembling the emotional turbulence often found in Du’s works.

Final (yun 韻)

A final may comprise a medial (yuntou 韻頭), a nucleus (yunfu 韻腹), and a coda (yunwei 韻尾), where the medial and nucleus together determine the final’s grade and whether it involves a rounded or unrounded articulation, while the coda influences its yin, yang, and ru divisions.

Grade (deng 等)

The division of grades is determined by the presence/absence of the medial i, as well as the tongue position and mouth opening size, and corresponds to the loudness of sound (Shen and Yang 1991, pp. 76–77). Jiang Yong (江永 1681–1762) pointed out that the first grade is profound, the second is moderate, while the third and fourth are minor, with the fourth being particularly minimal (Jiang 1995, p. 37). Based on Table 2, which compares only Li and Du, Li’s preference for the third grade and Du’s for the second and fourth grades do not directly reveal much about their differences in sound scale. However, when we compared each of them to QTS, which serves as a general representation of Tang poets and their typical poetic characteristics, using the same chi-square tests, we found that both Li and Du used significantly more first-grade finals and fewer third-grade ones than QTS. That is, despite their differences, they shared a common preference for the more profound finals over the minor ones. The power of the former appears particularly suitable to serve their grand themes and provides their poems with an extraordinary demeanour. For example, in Li’s couplet ɣuɑŋ kĭĕm muɑn kɑu dɑŋ tɒp ɣɑ nɑn kʰək tɕʰĭuŋ 黃金滿高堂, 荅荷難克充 (Even with a grand hall full of gold, I could hardly repay your kindness.), a predominance of first-grade finals is used, with the exception of kĭĕm 金 and tɕʰĭuŋ 充, and Du’s -ɑn tək pĭɛn luɒi kuŋ pʰɑŋ dɑ sien ŋu ɣuɑt 安得鞭雷公, 滂沱洗吳越 (How can I whip the Thunder God to bring a torrential downpour and wash away the unrest of Wu and Yue?) similarly features a predominance of first-grade finals, with the exceptions of pĭɛn 鞭, sien 洗, and ɣuɑt 越. The prevalent use of first-grade finals conveys a sense of majesty, which aligns well with the grand visions, high aspirations, and intense emotions embedded in the above verses.

Articulation (hu 呼)

Finals with the medial or nucleus u/w are considered rounded (he 合) in terms of the manner of articulation, while those without are unrounded (kai 開) (Shen and Yang 1991, p. 76). According to Table 2, Du features rounded articulation, in which the vocal cavity forms a rounded chamber, creating a sustained effect and evoking a sense of enclosure, mellowness, or depth. In his couplet -ĭwɐn ŋuɑi kɔŋ dəu dzuɑ pĭəu kĭwəi ɕwi tsĭɛŋ tɕʰĭuĕn tien ȶĭwɛn pʰĭwəi mĭwəi 苑外江頭坐不歸, 水精春殿轉霏微 (When I was sitting by the Qujiang Pond outside a royal garden, unwilling to return, the crystal spring palace grew hazy.), which follows an articulation pattern of 合合開開合開合, 合開合開合合合, Du employs a predominance of rounded articulations to enhance the haziness at dawn and his inner sense of gloom. On the contrary, the lack of medial or restriction to the vocal cavity as in Li’s verse tʰɑi bɐk ɣɑ tsʰɑŋ tsʰɑŋ 太白何蒼蒼 (How lush and verdant is Mount Taibai!) creates a different atmosphere of openness and grandeur.

Nucleus (yunfu 韻腹)

A nucleus is the main vowel in a final, crucial in determining its sonority and other phonetic qualities. It plays an important part in the symbolic effect of character pronunciations, making it worthwhile to explore in isolation. Table 2 shows Li’s preference for the nuclei “ɐ, o, a, ɑ, ɒ” and Du’s for “e, u, ə, i, ɔ”. The distinction between the two vowel sets is intuitively perceivable but requires further verification through an examination of their qualities, especially in terms of backness and height as determined by tongue position. These two features are often linked to brightness, shape, size, and strength. For instance, Mandelker (1983) found that high-front vowels are associated with lightness, brightness, sharpness, weakness, and small size, and low-back vowels with darkness, roundness, strength, and large size (p. 4).

Vowels are classified into front, central, and back based on tongue backness and into low, near-low, half-low, mid, half-high, near-high, and high based on tongue height (Xie 1987, p. 67). To facilitate a quantitative analysis, we assigned distinct numerical values to these positional properties. Specifically, we assigned 1, 2, and 3 to the front, central, and back positions, and 1–7 to the seven height positions, following the principle of greater values for greater backness/height. Based on the phonetic reconstruction system of Wang (1984), twelve different nucleus vowels are involved in our sound corpus, and their backness and height values are presented in Table 3.

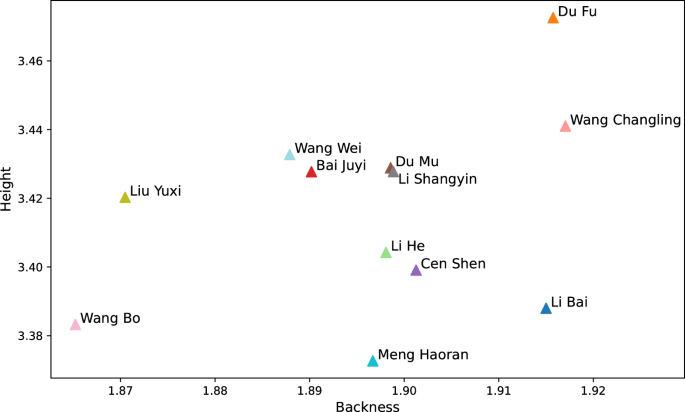

On this basis, the average backness and height values were computed for Li and Du by summing the product of each nucleus vowel’s count and its assigned backness/height value, followed by normalisation against the total count of nucleus vowels in each poet’s corpus. To facilitate analysis, a backness-height coordinate system was established. In this system, backness, which reflects the horizontal positioning of the tongue, is mapped to the x-axis, while height, representing the vertical positioning of the tongue, is mapped to the y-axis. In this way, the backness and height values of each poet serve as the coordinates that position the poet within the backness-height coordinate system. To contextualise the relative positioning of Li and Du within the broad landscape of Tang poetry, we included ten other prominent poets of the Tang dynasty, namely Bai Juyi (白居易, 772–846), Wang Wei (王維, c.701–between 761 and 768), Meng Haoran (孟浩然, 689–740), Li Shangyin (李商隱, c.811–c.859), Du Mu (杜牧, 803–c.852), Wang Changling (王昌齡, 698–c.756), Cen Shen (岑參, c.717–769), Liu Yuxi (劉禹錫, 772–842), Wang Bo (王勃, 650–676/684), and Li He (李賀, 790–816) as a backdrop for comparison. This resulted in a total of twelve data points, which were all mapped onto the backness-height coordinate system, as shown in Fig. 5. As illustrated, Li and Du are as back as each other but are both more back than all but one other poet. Meanwhile, they are situated at opposite extremes of the height dimension, with Du being the highest and Li the third lowest. To determine the statistical significance of these observations, we performed Z-tests on Li and Du’s average backness and height values respectively within the collective distribution of the twelve items under consideration. The outcomes of these tests, which assess whether the discrepancies in the two dimensions are due to random variation or reflect a genuine divergence from group averages, are detailed in Table 4, with the significance level set at 0.05. To verify the reliability of these findings, we also experimented with several other phonetic reconstruction systems, obtaining highly consistent results (see the Appendix for further details).

It presents poets as colour-coded triangles annotated with their names, positioned by average backness and height values of main vowels in their poetry.

Both Li and Du show a statistically significant preference for more back nucleus vowels, which are characterised by a tongue position towards the back of the mouth, creating a larger resonating cavity in the front of the mouth and contributing to a deep, resonant sound. Additionally, there is a cross-linguistic tendency for back vowels to be rounded, and both backing and rounding lower F2 (Zsiga 2013, pp. 136–137). This leads to a mellow and expansive quality in the sound, which aligns with the finding that, across many languages, front vowels are associated with smallness and back vowels with largeness (Sapir 1929; Thorndike 1945). This size symbolism of back vowels may extend to other dimensions, implying profundity and grandeur, and mirroring emotional and intellectual weight, both of which are characteristic of the poetry of Li and Du.

On the other hand, Li favours lower nucleus vowels, which are produced with the tongue positioned lower and further away from the roof of the mouth, allowing for greater mouth openness, and resulting in a more resonant and sonorous quality. This vocal quality evokes a sense of liveliness, vigour, and liberation, mirroring the expansive and unrestrained themes and strong emotions in Li’s works and enhancing the grandeur and vitality of his poetic style. Unlike Li, Du prefers higher nucleus vowels, which are produced with the tongue positioned closer to the roof of the mouth, requiring increased muscular effort, and resulting in a more closed mouth and a smaller vocal tract, which together create a more constrained and focused sound. This vocal quality indicates a pursuit of precision and fineness, as well as subtlety in contemplation, reflecting Du’s endeavour in introspective and nuanced exploration of social realities and human emotions in his poetry.

Coda (yunwei 韻尾)

Finals can be divided into three types based on their codas, namely yin (陰 no consonant coda), yang (陽 n/m/ŋ coda), and ru (入 p/t/k coda). Zhou Ji (周濟, 1781–1839) touched upon the respective and interactive effects of codas: when many yang characters are used together, there is a sense of chendun (沈頓 intoxicated, sinking); when many yin characters are used together, there is a sense of ji’ang (激昂 stirred, elevated); when a yin is used among multiple yang, it feels gentle but not weak; when a yang is used among multiple yin, it is high but not precarious (Zhou 1958, Preface, p. 4).

The results in Table 2 show that Li and Du feature yang and yin finals respectively. The nasal coda of a yang final is a voiced consonant, produced with the vibration of the vocal cords, creating a resonant, melodic effect (Xie 1987, p. 71). The lowering of the velum for nasalisation allows air to resonate in the nasal cavity, producing a distinct and prolonged co-articulatory effect on the nucleus vowel. This resonant effect provides a nasal final with a unique, mellow quality which may connote an immersion in the natural beauty, a spiritual experience, or overwhelming emotions, signifying a state of being lost in the moment, i.e., the intoxicated and sinking state described by Zhou (1958, Preface, p. 4). Taking Li’s scenery description lɑŋ duŋ kuɑn -ĭɛŋ tsĭɛŋ zĭĕm jĭaŋ kɔŋ ʑĭaŋ pĭuŋ (浪動灌嬰井, 尋陽江上風 Waves stir in the Guanying Well, as winds blow on the Xunyang River.) as an example, all the ten characters end with a nasal coda, bringing about an effect of sounds reverberating and echoing in the well and over the river. This effect enhances the grandeur and magnificence of the depicted scenery, reflecting Li’s inclination to elevate and embellish his personal experiences.

As to yin finals ending in pure vowels, they tend to produce a clear and pristine tone, as the vowel sounds are not affected by any subsequent consonant. The absence of a closing consonant also creates a distinct separation between syllables, contributing to a measured and deliberate rhythm that particularly suits contemplative themes. For example, in Du’s couplet dzi ku ɣĭəu kǐe lĭo ŋɑ ɣɑ kʰu -ɒi ɕĭaŋ (自古有羈旅, 我何苦哀傷 Living away from home has been common since ancient times; why should I alone feel sorrow and grief?), the use of nine consecutive yin finals adds a sense of intermittent thought flow, reflecting his dialectical contemplation of history and life after a prolonged period of wandering due to warfare. Interestingly, the three velar initials k, k, and kʰ, appearing intermittently throughout the couplet, also contribute to the effect of intermittence. Additionally, the stand-alone yang final at the end of the couplet creates a sharp contrast against all preceding yin finals, deepening and amplifying the poet’s sorrowful mood with its resonant and prolonged quality.

Tone (diao 調)

The tonal conditions in Tang poetry remain a subject of ongoing enquiry. The Japanese Siddham scholars placed particular emphasis on pronunciation accuracy, making their records, such as the works of Annen (安然 841–c.898), an important source for studying Middle Chinese tonal values. However, interpretations of these materials vary among phonologists, and definitive conclusions are yet to be reached. The analysis presented below is based on the current research outputs on these materials.

Table 2 shows that Li and Du prefer the level and departing tones, respectively. Mei (1970, pp. 109–110) described the level tone in Middle Chinese around the eighth century as long, even, and low in pitch, and the departing tone as losing its original length, with a rising contour, and high in pitch. However, Ding (1975, p. 12) proposed that the departing tone might have a falling contour. After comparing different Siddham materials, Yuchi (1986) found that Mei’s interpretation aligns more closely with the views of the Siddham scholars. Zhengzhang (2003) suggested that by the middle stage of Middle Chinese, the four tones had been further subdivided into light/heavy or yin/yang variations, with the level tone showing pitch contours of 33/11, and the departing tone 42/232. Rai (1989) reconstructed the level tone as slightly falling in contour and the departing tone as rising. According to the mainstream opinion of these scholars, the level tone is most likely to be even or slightly falling, low or mid in pitch, and possibly long. It is reasonable to consider that its evenness and length can help create a sense of spaciousness. This conceivable effect appears to align well with Li’s unrestrained style and his preference for describing vast landscapes and the sublime. The qualities of the departing tone are more disputable and will not be discussed further in this analysis.

In terms of the level-oblique (pingze 平仄) division, Li and Du favoured the level and oblique tone categories, respectively. The distinction between level and oblique tone categories remains debated, with differing views on whether it is based on heaviness, length, pitch, or evenness. Mei (1970, p. 108) suggested that it is most likely based on either length or pitch. Ding (1975, p. 13) argued that it lies in evenness versus unevenness. Hirata (2001), after analysing various opinions, concluded that it is most likely pitch-based, with the level tone being low and the oblique tones being high. Liu (2010, p. 242) reckoned that the level tone is smooth and prolonged, whereas the oblique tones are abrupt or dynamic. In summary, the level tone is probably longer, lower, even, and smoother, while the oblique tones are shorter, higher, uneven, and more abrupt. These qualities of the level tone contribute to a sense of extension, grandeur, and fluidity, which align well with Li’s bold, unrestrained, and ethereal style. In contrast, the qualities of the oblique tones tend to suggest unevenness, precipitousness, uneasiness, intensity, and variation, which correspond to Du’s emotional complexity and rhythmic intricacy.

Conclusion