LmCen−/− based vaccine is protective against canine visceral leishmaniasis following three natural exposures in Tunisia

Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a vector-borne illness caused by a protozoan parasite belonging to the genus Leishmania. In the Old World, it is transmitted through the bites of infected female sand flies belonging to the genus Phlebotomus. In Asia and Eastern Africa, VL is primarily caused by Leishmania donovani, with humans serving as the reservoir for the pathogen1. In Latin America and the Mediterranean regions, Leishmania infantum (synonymous with L. chagasi) is the causative agent1. Human visceral leishmaniasis (HVL) is a systemic disease, predominantly affecting vulnerable demographics such as children and old people, individuals with underlying health conditions, comorbidities, and/or immunosuppressive. If left untreated, HVL is fatal in over 95% of cases; it carries the potential for outbreaks and high mortality rates2. Annually, an estimated 50,000 to 90,000 new cases of HVL arise globally and only 25–45% of these are reported to the World Health Organization (WHO)2.

In Latin America and the Mediterranean regions, VL is a zoonotic disease, with dogs serving as the main reservoir. There is a significant correlation between the high prevalence of dog infections and the elevated risk of human cases3, showing that the control of HVL hinges upon effectively managing canine leishmaniasis4.

Canine visceral leishmaniasis (CVL) is a multisystemic and chronic disease that frequently culminates in death among infected dogs. Signs of the disease can be manifested locally or systemically, either appearing alone or in various combinations. The presentation of the clinical signs varies, and the progression can be slow, contingent upon the immune response of the dogs5. Some dogs infected with Leishmania can be resistant and effectively control the infection, remaining asymptomatic for periods extending to years. On the other hand, susceptible dogs may show either few or severe symptoms, with untreated cases often resulting in the death of the infected dog. The treatments currently available for CVL are not effective. Moreover, the limited number of drugs that have progressed to clinical stages in human medicine are unlikely to be developed for commercial use in dogs6.

Vaccination strategies, along with improved treatment, diagnostic methods and vector control, serve as public health tools for controlling CVL. Mathematical models have demonstrated that reducing the incidence of leishmaniasis in the dog population hinges on the effectiveness of vaccination efforts7. Developing vaccines against CVL is a significant cost-benefit measure, serving as a prophylactic method for combating this vector-borne disease. Such vaccines not only safeguard dogs but also prevent the spread of leishmaniasis as a zoonotic infection in humans8. A canine vaccine remains a promising approach for controlling CVL, given its complex epidemiology in areas where zoonotic CVL is prevalent.

In humans the process of leishmanization in which deliberate infections with a low dose of virulent Leishmania major provides greater than 90% protection against reinfection and has been previously used in several countries of the Middle East9. A live-attenuated Leishmania dermotropic parasite providing a complete array of antigens of wild-type parasite that does not cause disease but elicits protective immunity similar to “leishmanization” could be a safe and effective vaccine candidate. Our laboratory has developed a highly promising live attenuated Leishmania vaccine through targeted deletion of the Centrin gene-1, employing genome editing technologies-CRISPR-Cas910. Centrin in Leishmania is a calcium-binding protein situated in the basal body, crucial for its duplication and segregation. Deletion of the Centrin gene affects the growth and differentiation specifically in the Leishmania amastigote form, causing apoptotic death of the parasite9. These apoptotic parasites are cleared by the immune phagocyte system10,11. The Leishmania major (LmCen−/−) live attenuated vaccine has demonstrated safety, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy against L. major and L. donovani challenges using either needle or sand fly mode of infection with virulent Leishmania parasites in mice and hamster models of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) and visceral leishmaniasis (VL), respectively12,13.

Previously, we have demonstrated immunogenicity of Leishmania donovani centrin gene deleted parasites (LdCen−/−) in dogs, that elicits lymphoproliferative responses in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. LdCen−/− induced higher frequencies of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells14. Furthermore, dogs vaccinated subcutaneously with a single dose of 107 LdCen−/− parasites showed a decrease up to 87.3% in parasite burden 18 months after an intravenous needle challenge with 107 L. infantum parasites15. The long-term effectiveness of LdCen−/− can be attributed to the selective activation of a type 1 immune response (Th-1), which subsequently reduces the parasite load in the bone marrow, even 24 months post-infection with L. infantum15. The efficacy observed after administering only a single dose of the LdCen−/− vaccine, without the use of an adjuvant, was comparable to the protection conferred by three doses of commercially available canine vaccines “Leishmune”14. The study showed that LdCen−/− as a highly effective and efficient vaccination strategy for controlling CVL when the dogs were challenged intravenously15. However, the efficacy of the LdCen−/− vaccine in dogs naturally exposed to L. infantum was unknown.

Many formulations of Leishmania vaccines, evaluated in preclinical models have failed to protect against natural transmission by infected sand fly bites suggesting that the vector transmission of Leishmania can abrogate vaccine-induced protective immunity16. To validate vaccine-induced immunity and estimate protective efficacy, natural exposure to infected sand flies is necessary16. Serafim et al.17 reviewed the contribution of vector competence and the success of Leishmania transmission. Factors such as sand fly saliva, egested parasite molecules, vector gut microbiota, and bleeding modulate the early innate host response to Leishmania establishment in the skin after an infected bite. Early immune events at the bite site govern Leishmania survival and vaccine outcomes. The sand flies transmitting the infection through their bites have been implicated in the efficacy of vaccines16. Thus, development of symptomatic CVL in canine models may take repeated exposures to the infected sand flies, therefore estimating the efficacy of vaccines requires testing in natural transmission conditions with symptomatic CVL as study end point.

In the present study, we attempt to provide the correlates of immunity that will predict the L. major Centrin (LmCen−/−) vaccination success against natural exposure. The aims of the work were as follows; in the first cohort study to establish the optimal LmCen−/− vaccine dose required to confer long-term immunity in dogs against L. infantum infection. The second cohort study was to assess the effectiveness of the LmCen−/− vaccine in dogs through natural exposure to L. infantum, in an endemic focus located in Northern Tunisia. In addition, analyze and compare the biochemical, immune response, and clinical characteristics of both unvaccinated and vaccinated dogs following three seasonal challenges with L. infantum-infected sand fly vectors under natural settings, to evaluate the vaccine’s impact on the dogs’ overall health and immune responses.

Results

Safety characteristics of LmCen−/− vaccine in dogs

Twelve healthy beagle dogs seronegative for L. major were included in the study. There are three groups, and each group has four dogs. The control group corresponds to dogs injected with the culture medium (M199) of parasite. The two test groups were immunized with either 106 or 107 GLP-LmCen−/− parasites by intradermal (ID) injection of 100 µl of inoculum in the ear (Fig. 1a). Clinical examination was performed daily for the next two weeks post-inoculation (prime). All vaccinated and control dogs remained healthy. No adverse reactions such as skin lesion, local lymphadenitis or serious clinical signs were observed either in vaccinated nor in the control groups.

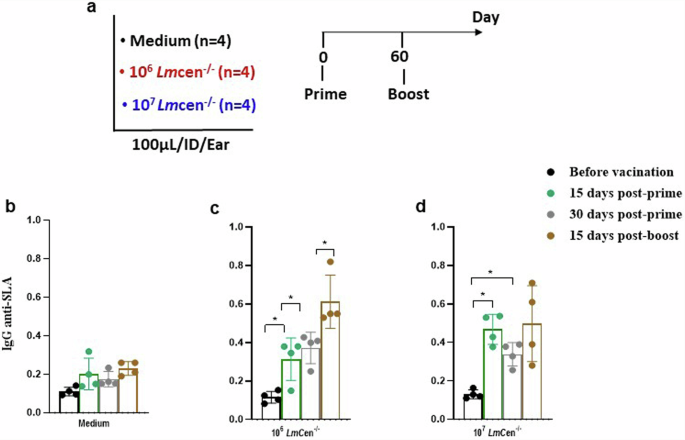

a Protocol for analysis of the Immunogenicity of LmCen−/−. Three groups of dogs were included in this step: dogs receiving 106 or 107 live LmCen−/− parasites and as negative control dogs receiving 100 µl of medium. Immunization was done by intradermal injection of 100 µl of vaccine in the ear of dog. Boost with vaccine was done at the same conditions as the first immunization at an interval of 2 months. b–d Histograms represent the mean of total IgG anti-SLA at different kinetics. Vertical bars indicate the standard deviation (SD). Total IgG titers are measured using SLA from L.major. Statistical analyses are done using GraphPad Prism, *p < 0.05: difference is statistically significant.

Biochemical (Urea, total protein, creatinine, ALT, AST, and GGT) and hematological analyses (red blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, VGM, TCMH, CCMH, leukocyte, PNE, lymphocytes, monocytes and, platelets) were performed at 15 days post-prime (Supplementary Table 2). Hematological and biochemical values remained in the normal ranges after immunization for the majority of vaccinated and control groups indicating a healthy status, except some dogs showing mild changes in these parameters, which may be linked to the stress at the time of blood collection. Globally, these results showed that the LmCen−/− vaccine is safe and well tolerated by dogs.

LmCen

−/− vaccine immunogenicity in dogs

Two months post-prime, dogs received a booster injection with either 106 or 107 GLP-LmCen−/− parasites by ID injection of 100 µl of inoculum in the ear (Fig. 1a). IgG anti- SLA levels were measured in sera sampled before vaccination, 15 and 30 post-prime and 15 days post-boost. As shown in Fig. 1b, low levels of total IgG anti-SLA were observed in dogs before vaccination (IgG level OD ≤ 0.23; cut-off measured in healthy dogs). Immunization with 106 promastigotes GLP- LmCen−/− induced an increase of IgG levels at both 15 days and 30 days post-prime. The difference between IgG levels measured before vaccination and at 15 as well as 30 days post-vaccination was statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1c). Following the boosting injection, a significant increase in IgG titers in vaccinated dogs was observed compared to titers measured before vaccination as well as 15 and 30 days post-prime (Fig. 1c). Similar patterns following the immunization with 107 promastigotes GLP-LmCen−/− were observed. Increase in IgG levels was noticeable starting two weeks post-vaccination and did not increase at 15 days post- boost (Fig. 1d).

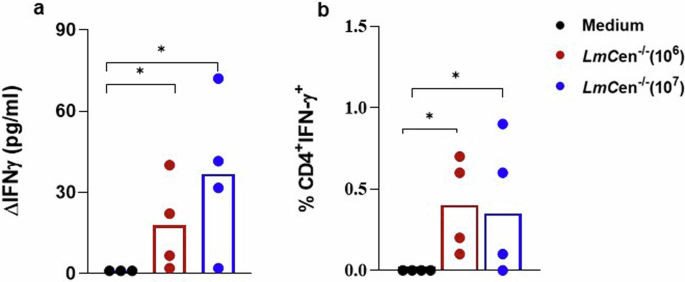

Cellular immune response specific to Leishmania was evaluated at one month post-prime. As shown in Fig. 2a, SLA stimulation induced production of IFN-γ by PBMCs isolated from dogs immunized with both 106 or 107 GLP- LmCen−/− and was significantly higher in dogs immunized with either 106 or 107 GLP- LmCen−/− compared to controls (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2a). After the boost, FACS analysis showed significantly higher production of IFN-γ by CD4+T cells in vaccinated dogs compared to control (Fig. 2b). Together these results showed that the intradermal injection of both 106 and 107 GLP-LmCen−/− promastigotes induced similar humoral and cellular immune response specific to Leishmania parasite. Based on the similar immune response, we used 106 LmCen−/− parasites for vaccine efficacy studies.

One month post-Immunization, PBMCs from immunized dogs (106/107 LmCen−/−) or control groups (medium) were incubated with soluble Leishmania antigens (SLA, 10 µg/ml). a IFN-γ levels measured in cell culture supernatants collected at 72 h using sandwich ELISA. b Percentage of CD4+T cells producing IFN-γ in response to stimulation with SLA. Statistical analyses are done using GraphPad Prism, *p < 0.05: statistically significant difference.

Natural Challenge of dogs in the endemic area for transmission of L. infantum

In this second cohort study, 11 vaccinated (injected with 106 LmCen−/− parasites) and 11 control dogs (injected with PBS) were transported to an endemic area for L. infantum transmission in North Tunisia. The dogs resided in the endemic area for 3–5 months per year to be bitten by naturally infected sandflies during three successive seasons in 2019, 2020, and 2021. The dogs were vaccinated with 106 LmCen−/− intradermally in the ear every time before they were transported and exposed in the endemic area (Fig. 3a).

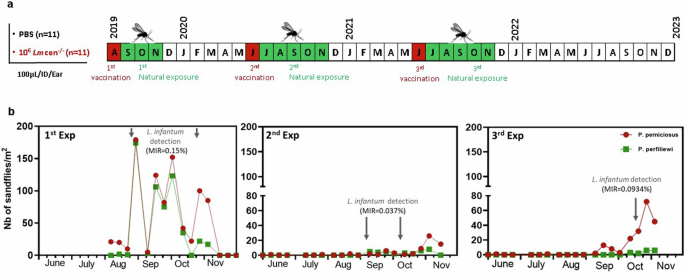

a Dogs receiving 106 LmCen−/− (n = 11) and those receiving 100 µl of PBS (Negative control, n = 11) are transported to an endemic area for the transmission of L. infantum (North of Tunisia) during three successive seasons 2019, 2020 and 2021. b Phenology of P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi in the exposure site. One-month post-prime, dogs were placed in a rural area (36°58’N, 10°03’E) during September-October 2019, June-November 2020, and September-November 2021. The densities of P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi as well as their infection prevalence with L. infantum were assessed during August-October 2019 (1st exp), June-November 2020 (2nd exp), and August-November 2021 (3rd exp). The phenology of collected sand fly species by sticky traps was studied during the same periods in the same site. Density of sandflies was recorded as the number of sand fly species per m2 of sticky trap. The infection prevalence of collected sandflies by CDC light traps was assessed during the same periods. The minimum infection rate (MIR) of sandflies by Leishmania parasites defined as the number of positive pools divided by the total number of tested specimen × 100.

Phenology of sand fly circulating in the exposure site was assessed in 2019, 2020, and 2021. A total of 1048 collected sandflies by sticky traps were identified individually to species level during the time. Collected sandflies belonged to two genera: Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia. During the three exposition periods, P. perniciosus was the most abundant sandfly species followed by P. perfiliewi. A small peak early in June and a larger one in September-October characterize the seasonal activity of these sand-fly species (Fig. 3b). Prevalence of sandflies Leishmania-infection was evaluated during the three exposure periods. A total of 9860 female sandflies were tested for the presence of Leishmania. The minimum infection rates (MIRs) of sand flies for L. infantum observed in 2019, 2020, and 2021 were 0.15% (2/1290), 0.037% (2/5357), and 0.09% (3/3213), respectively (Fig. 3b). The seasonal variation of the infection prevalence of sandflies with L. infantum showed a peak during September–October.

IgG specific for sand fly saliva and Leishmania in dogs after natural exposure in the endemic area

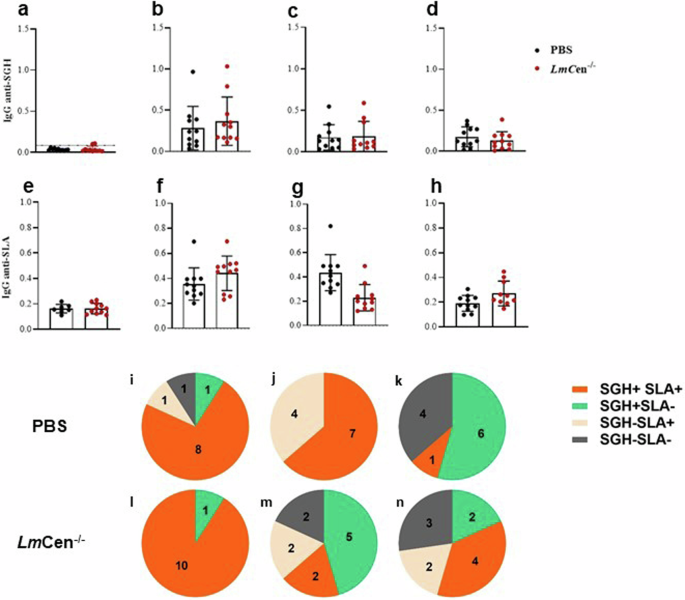

We investigated the exposure to sand fly’s bites and the infection with Leishmania of dogs by measuring the titer of total IgG anti- SGH and anti- SLA at return from the exposure site following each transmission (Fig. 4). After the first exposure, 11 dogs from the vaccinated group and 9 dogs from the non-vaccinated group showed high titers of IgG anti-SGH indicating that they have been bitten by sandflies (Fig. 4b). Titers of IgG anti-SGH were lower among dogs after their return from the field following the 2nd and 3rd exposure (Fig. 4c, d).

IgG anti- SGH and anti-SLA are measured in sera from dogs immunized with LmCen−/− at a dose of 106 and those receiving 100 µl of PBS (Negative control). Titers of IgG anti-SGH measured in dogs before (a) or at return from the field after successive expositions 2019 (b), 2020 (c) and 2021 (d). Titers of IgG anti-SLA before (e) and after the exposure in the endemic area (f–h) measured using SLA from L.infantum. Histograms represent the mean of IgG anti-SGH or anti-SLA for each group. Bars represent the standard deviation for each group. Pie charts represent number of dog positive and/or negative for IgG anti-SLA and IgG anti-SGH at return from the field in 2019 (i–l), 2020 (j–m) and 2021 (k–n). Cutoff of IgG anti-SLA is fixed at OD = 0.23; cutoff for IgG anti-SGH fixed at OD = 0.08.

Total IgG anti-SLA was detected in 10 dogs from the vaccinated group and 9 dogs from control group a return from the field after the 1st exposure (Fig. 4f). The IgG anti-SLA titers were similar after each exposure, except two dogs, one vaccinated and one unvaccinated, showing high titers after the 2nd and 3exposure, respectively (Fig. 4g, h). Variation of IgG anti-SLA titers in individual dog are shown in supplementary figure 1.

Next, we analyzed the number of dogs that were positive for IgG anti-SGH (SGH + ) or IgG anti-SLA (SLA + ) after each exposure to sand flies in both groups. The total number of control and vaccinated dogs that became SGH + SLA+ were 18 dogs (8 PBS/10 LmCen−/−) after the 1st exposure (Fig. 4i–l), 9 dogs (7 PBS/2 LmCen−/−) after the 2nd exposure (Fig. 4j–m), and 5 dogs (1 PBS/4 LmCen−/−) after the 3rd (Fig. 4k–n).

Impact of the vaccination of dog with LmCen

−/− on the outcome of L. infantum infection

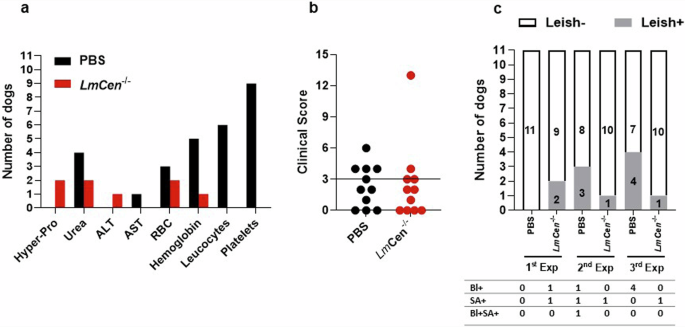

To ascertain vaccine-induced long-term protection, dogs were screened for biochemistry and hematologic parameters at the end of this cohort study (three months after the 3rd exposure). The dogs from PBS control group showed hematologic alterations, as anemia with a decreases of red blood cells/RBC (3/11) and hemoglobin/Hb (5/11) compared with vaccinated dogs RBC (2/11) and Hb (1/11) (Fig. 5a). The leukocytosis (6/11) and thrombocytopenia/PLT (9/11) were prevalent in the majority of the control dogs. The leukocytosis and PLTs were not detected in any of the vaccinated dogs (Fig. 5a).

a Results of biochemical, hemogram and (b) clinical score after the 3rd exposure in the endemic area. c The PCR parasite load in the whole blood/Bl and spleen aspirate/SA every year during, six months after the successive seasons 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Typically, the CVL clinical signs included, but were not limited to general lethargy, inappetence, cachexia, dermatitis, chronic ulceration, uveitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, onychogryphosis, polyarthritis, epistaxis and/or lymphadenopathy. We performed clinical examinations using a clinical score (Supplementary Table 3). In our study the number of dogs with clinical signs attributed to leishmaniasis were 4 of 11 dogs (CS > 3) in the control group, while 2 of 11 dogs showed CS > 3 in the vaccine group (Fig. 5b).

Individual dog was considered and confirmed case of canine leishmaniasis when it presented a Leishmania positive PCR test in either the blood and/or spleen aspirate. The development of CVL cases confirmed by the parasite detection assessed 6 months after each natural exposure. L. infantum was detected in 3/11 (2nd exposure) and 4/ 11 (3rd exposure) in the PBS control dogs (Fig. 5c). On the other hand, lower number of cases of leishmaniasis was observed in the vaccine group 1/11 (1st exposure), 2/11 (2nd exposure) and, 1/11 (3rd exposure) (Fig.5c). Together clinical exam and parasite detection results indicated that in the control group we have 3 oligosymptomatic compared to 1 symptomatic dog in the vaccinated group. At the last time point of the three years cohort field study, the efficacy of the LmCen−/− vaccine was 82.5% based on the calculation of the odds ratio (OR).

Evaluation of the immune response within the dog’s spleens showed overall similar induction of both IFN-γ, IL-10 between dogs that had either received PBS or LmCen−/− vaccine, after the three exposures to sand fly bites in the field (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, we noted a trend of higher IFN-γ induction in vaccinated dogs compared to control dogs. One of the dogs from the LmCen−/− vaccinated dogs showed high levels of IFN-γ (Supplementary Fig. 2). Similarly, there is a trend of lower IL-10 levels in vaccinated dogs compared to control dogs. In addition, TNF- α level was similar in dogs except one from unvaccinated dogs showing high level (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Discussion

CVL is an important vector-borne disease caused by L. infantum in the Mediterranean basin, in Latin America, in the Middle East, and China18. Due to its severity in dogs and its zoonotic nature, the prevention of this infection is essential for both dog and human health18. Thus, an effective vaccine against L. infantum will reduce the incidence of CVL and subsequently the incidence of HVL as has been shown following dog vaccination with Leishmune® in Brazilian endemic areas19.

A live-attenuated Centrin deleted Leishmania donovani parasites (LdCen−/−) have been shown to elicit protective immunity against Leishmania infection in murine models and dogs14,20. Despite the strong protection induced by LdCen−/− vaccine in L. infantum-infected dogs, the potential risk of visceralization due to the use of viscerotropic parasite precluded its use against VL15. However, previous studies demonstrated that infection with some Leishmania species could confer cross-protection against different species of Leishmania. Cutaneous infections with L. major confer protection against L. infantum infection in murine model21. Genetically modified live-attenuated L. donovani parasites protect against Leishmania mexicana, etiologic agent of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Central America22. Similarly, genetically modified live- attenuated L. mexicana parasites protect against the visceral form caused by L. donovani23. For the aforementioned reasons, we have previously demonstrated that a live attenuated centrin gene-deleted dermotropic Leishmania major (LmCen−/−) vaccine is safe and effective against lethal VL transmitted naturally via bites of L. donovani-infected sand flies in hamster model that mimics human disease13. Sand fly mediated challenge infection models have been considered the gold standard for the evaluation of efficacy characteristics of experimental vaccines. Accordingly previous studies from our group demonstrated the efficacy in a sand fly mediated challenge models. However, it is increasingly becoming clear that successful infection causing symptomatic disease through colonized sand flies may require multiple infected sand flies feeding on the animals. It is not clear if these environmentally controlled infection models work effectively in canine models. Thus, testing the efficacy of vaccines maybe better accomplished in a natural habitat where the infected sand flies are allowed to feed on the immunized dogs. Our results highlight the importance of multiple cycles of infection in a natural habitat to induce symptomatic VL in dogs and that the protection observed in the immunized dogs in a quasi-Phase III study may be a true indication of the efficacy.

In this study, we demonstrated the safety, the immunogenicity, and the efficacy of live attenuated LmCen−/− vaccine against CVL under natural settings in a highly ZVL endemic focus. GLP-LmCen−/− confers robust and durable protection against lethal VL transmitted naturally via bites of L. infantum-infected sand flies and prevents development of CVL. Intradermal injection of GLP-LmCen−/− is safe in dogs, without any adverse clinical sign or abnormal hematological or biochemical profile. Similar results have been described previously in the hamster model13.

Immunization with live attenuated GLP-LmCen−/− parasite induced production of high titers of IgG anti-Leishmania with predominance of IgG2a subclasses in dogs suggesting a Th-1 cellular immune response (data not shown). Following a boosting injection, the analysis of the cellular immune response in immunized dogs one month post-prime indicated a pro-inflammatory environment associated with expression of Th-1 cytokines. Stimulation of peripheral blood cells with L. major soluble antigens induced production of IFN-γ by CD4+T cells. These results are similar to those described previously in the mice and hamster models showing that the protection is mediated by IFNγ-secreting CD4+ T-effector cells and multifunctional T cells12,13. Similarly, immunization with cutaneous causing Leishmania species such as LmexCen−/− down-regulated the disease promoting cytokines IL-10 and IL-4 and increased pro-inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ resulting in higher IFN-γ/IL-10 and IFN-γ/IL4 ratios compared to non-immunized13. LmexCen−/− immunization also resulted in long-lasting protection against L. donovani infection13,23. Phase I and II clinical trials in dogs testing the LBSap-vaccine prototype, Leishmune and Leish-Tec vaccines which include adjuvants showed that they are able to induce a strong production of IFN-y by CD4+T cells, only after three-dose vaccine course at 21-day intervals. Such commercially approved Leishmania vaccines for dogs use adjuvants to enhance the immune response24. On the contrary our study with LmCen−/− vaccine showed that it is able to induce a Th-1 profile with a single dose without an adjuvant.

The protection levels observed under controlled environment in mice and hamsters12,13 prompted us to investigate the potential of live attenuated GLP-LmCen−/− vaccine to control L. infantum infection of dogs in a natural infection environment. One-month post-prime, GLP-LmCen−/−-vaccinated dogs and unvaccinated controls were transferred to a CVL endemic focus located in North Tunisia. We conducted a randomized controlled study during three successive transmission seasons of L. infantum to evaluate the efficacy of live attenuated GLP-LmCen−/− vaccine. An entomological investigation performed in the exposure site showed the high densities of P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi, main vectors of CVL in the Western Mediterranean basin, during the first exposure period compared to the 2nd and 3rd one. This could be attributed to several ecological factors including high temperature and drought. Prevalence of the sandflies infection with L. infantum, the only circulating Leishmania parasite in the study site, was high during the first exposure period comparing to the 2nd and 3rd ones. The result is corroborated with the titers of IgG anti-SGH measured in sera of vaccinated and unvaccinated dogs at return from the exposure sites. Antibody responses against sand fly saliva proteins are thought to limit initial parasite establishment25. Regarding the immune response elicited against L. infantum, the anti-SLA antibody response was similar within both studied groups after the 1st exposure. However, IgG anti-SLA titers were lower after the 2nd and 3rd exposure with a tendency to decrease in vaccinated animals except one dog showing the highest titer of anti-SLA after the 3rd exposure, which later developed clinical symptoms of CVL. Since the IgG titers varied between the first and subsequent exposures, the initial increase in the antibody response is not indicative of protection observed. In Leishmania infection humoral responses were not a good correlate of protection compared to cellular response. Thus, we tested IFN-γ levels and the frequencies of IFN-γ + CD4 T cells as a correlate of protection. In consistence with our data, previous studies suggested that Leishmania-specific immunoglobulins apparently play no role in mediating protection and are often associated with disease exacerbation26,27. Seroconversion of the humoral response against Leishmania, in addition to clinical and parasitological criteria, were used for screening of infected dog to assess the vaccine-induced protection28. However, there has been difficulty to discriminate vaccine- from infection-induced antibody responses by the serological tests29.

Efficacy of the GLP-LmCen−/− vaccine was evaluated based on a three-year follow-up of immunological, parasitological, biochemical, hematological and clinical parameters. After three exposures in the endemic focus, parasites were detected in four dogs from the non-immunized group and in one dog from the immunized group. CVL clinical symptoms appeared only after the 3rd exposure. It was reported, previously, that the period between infection and development of clinical disease might range from months to years in dogs26. At the end of the study, we noted that among control group, three were oligosymptomatic (CS≤3) and one was symptomatic (CS > 3). However, one of the vaccinated dog that was positive for PCR showed symptomatic active infection status. Interestingly, we noted that after the first exposure, two vaccinated dogs with subpatent (PCR positive without any symptom) converted to the Leishmania-free status. Similar results were described by Oliva et al. 2014 showing that subpatent dogs (PCR positive only) were able to revert to the Leishmania-free status, and this was more frequently seen in the vaccinated group than the control group30.

Considering the important role of spleen in the immune response, we analyzed the cytokine profile in vaccinated and unvaccinated dogs after the last exposure in the endemic area. Our results showed a heterogeneity in the immune responses among dogs belonging to the same group. It might be due to the difference in the status of the infection at the end of the study. Overall, there was trend towards higher IFN-γ expression levels in vaccinated dogs compared to those from the control groups. In contrast, there was a trend towards lower IL-10 levels within these dogs compared to non-vaccinated ones. These results corroborate in part with those described in LmCen−/− immunized and L. donovani challenged hamsters. Spleen cells from hamsters produced significantly higher Th1-associated cytokines including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and reduced expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10, IL-21, compared to non-immunized challenged animals15. Marginal differences in IFN-γ, IL-10 and TNF-α level between the vaccinated and unvaccinated dogs reflect the indeterminant nature of the infection initiation under natural exposure conditions in the field, contrary to post challenge immune response in animals (mice or hamsters) under controlled laboratory environment. Typically, we have observed an elevated IFN-γ level both 48 h and 2 weeks post-challenge upon restimulation with Leishmania antigens in vitro in mice immunized with LmCen−/− parasites12. Since the splenic aspirates from the dogs were collected several months after the exposure to sandflies, elevated IFN-γ levels are not expected to be found at the time point when the samples were obtained. Mild or moderate histopathologic changes in the skin, liver, spleen, and popliteal lymph node, often accompanied by a lower parasitic burden; and mixed cytokine profile, with high preferential IFN-γ production, TNF-α, and IL-13 have been considered as resistance biomarkers in CVL31,32.

Vaccine efficacy was established based on clinical manifestations observed among control and vaccinated groups in addition to detection of parasite in blood or spleen of dogs. The efficacy of the vaccine in the prevention of CVL in this study was 82.5%. Moreover, considering only vaccinated animals, protection rate reached 90%, according to parasitological criteria. The follow-up of dogs lasted for three years, which strengthens the interpretation of our results. On the other hand, in studies where dogs were immunized with subunit vaccines such as LiESP/QA-21 vaccine (CaniLeish, Virbac, France) and exposed to natural L. infantum infection during two consecutive transmission seasons, in two highly endemic areas of the Mediterranean basin, the efficacy was 68.4% with a protection rate of 92.7%30. Similarly, a field trial to evaluate Leish-Tec® (rA2 protein-saponin vaccine) against CVL in Brazil showed an efficacy rate of 42% based on parasitological and xenodiagnostic exams33. In our study, xenodiagnosis was performed upon the return from the field site after each exposure period. Xenodiagnosis results were negative for all dogs (data not shown) which might be related poor sensitivity of xenodiagnosis for this objective and also the clinical status of dogs and their infectivity. Similar to our results, serial xenodiagnoses to assess the infectivity of dogs naturally infected with L. infantum, showed that asymptomatic dogs were unable to infect L. longipalpis females, while oligosymptomatic animals were infective at very low rates34, therefore using PCR is justified for parasite detection. Further, it has been shown that humans who recover from Leishmania major infection can be protected lifelong against future L. donovani infection35. In the contrary, Leishmania vaccine formulations using subunit, DNA or, heat-killed parasites are limited for a single or few reliable antigens or need adjuvants, have not been demonstrated to be protective against natural sand fly mediated infection and have failed to achieve satisfactory results in clinical trials36,37,38, even though they were shown to be safe. Therefore, these studies suggest that to achieve a long-range efficacy one needs a complete array of parasite antigens, which can be achieved using genetically modified live attenuated parasite.

Taken together, our results show that live attenuated L. major parasites LmCen−/− vaccine is safe and efficacious against L. infantum in dogs resulting in the control of CVL development in natural transmission settings. Further, it provides assurance that LmCen−/− parasites can be safe and efficacious in human clinical trials.

Methods

Ethical considerations

The maintenance of the dogs and the experimental procedures used in this research program followed the Animal Care and Use Protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute Pasteur of Tunis, Tunisia (2018/01/I/ES/IPT/V0). The number of dogs was kept to the minimum consistent with significance of expected results in order to comply with the “three Rs” of animal welfare (Replace, Reduce, Refine).

Leishmania isolates and culture

Experiments were carried out using two Leishmania (L.) isolates: L. major zymodeme MON25 (MHOM/TN/95/GLC94) and L. infantum zymodeme MON24 (MHOH/TN/07/LV59) collected from human cutaneous and visceral cases, respectively. These two isolates were available from the biobank of Leishmania species at the Institute Pasteur of Tunis. Cryopreserved Leishmania promastigotes were stabilized and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Lonza), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. The RPMI culture was incubated at 26 °C and maintained by adding medium every 72 h.

Preparation of soluble Leishmania antigens

Stationary-phase promastigotes were used for preparation of soluble Leishmania antigens (SLA) as previously described39. Briefly, promastigotes were washed four times in cold PBS pH 7.5 and resuspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. The suspensions were sonicated on ice by six times 10 s pulses. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 27,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C and the supernatant collected and clarified by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 4 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was then dialysed against sterile phosphate-buffer saline (PBS) filtered through a 0.2 mm filter and stored at −80 °C. SLA prepared from L. major and L. infantum were used to measure the IgG anti-Leishmania levels after immunisation with LmCen−/− and after natural challenge, respectively.

Preparation of the salivary gland homogenate

Phlebotomus perniciosus used in this study are from a colony originated from Tunisia and maintained at the Unit of Vector Ecology in the Pasteur Institute of Tunis40. Laboratory-colonized F13 females P. perniciosus were dissected at three to seven days after emergence. Salivary glands were removed under a stereo microscope in cold PBS (pH 7.4) at −80 °C. Salivary glands were disrupted by three cycles of freezing-thawing to prepare the Salivary Gland Homogenate (SGH)41.

Protocol to evaluate LmCen−/− immunity under controlled environment

Three groups composed each of four healthy beagle dogs aged between 6–8 months were included in this phase of the study. Vaccinated dogs and control groups received 106 or 107 live attenuated GLP-LmCen−/− parasites and 100 µl of medium (M199), respectively. Immunization was performed by intradermal injection (ID) of vaccine or medium in the dog’s ear. Boost with vaccine was done under the same conditions at an interval of 2 months post-prime. Sera sampled at different time point (before immunization, 15 and 30 days post-prime, and 15 days post-boost) were used to measure the IgG anti-Leishmania antibody levels. Heparinized blood sample was used for purification of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) using Ficoll- Paque (GE Healthcare).

Safety evaluation

To determine the safety of LmCen−/− vaccine, physical examinations of dogs receiving injection of the vaccine or medium (control group) were carried out daily for 2 weeks post-prime. Safety is defined based on the presence or the absence of any lesions at the inoculation site in addition to the development of clinical symptoms such as lymphadenopathy, weight loss, splenomegaly, conjunctivitis, skin involvement, and onychogryphosis. Hematological (WBC, RBC, HGB, HCT, PLT, LYM) and biochemical parameters (Creatinine, Urea, ALT, AST and Total protein) were measured at 2 weeks post-immunization.

Study design to test vaccine efficacy under natural settings

The efficacy of LmCen−/− vaccine was evaluated basing on dog’s exposure to bites of sand fly, vector of L. infantum, under natural setting. Twenty-two healthy beagle dogs (male and female) aged between 6 and 48 months seronegative for Leishmania antibodies were included in this phase of the study. Dogs are subdivided into two age-matched groups: eleven dogs received an intradermal injection of 106 GLP-LmCen−/− parasites in the ear forming the vaccinated group and the remaining 11 dogs were inoculated with 100 µl of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) forming the negative control group. Dogs received a boosting injection yearly in the same conditions as the prime injection. One-month post-immunization, dogs were transported to a CVL endemic focus for transmission of L. infantum located in Northern Tunisia (Utique, governorate of Bizerte), recognized for the abundance of P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi, vectors of L. infantum42. Dogs were housed in a private open-air shelter with fenced -open area to roam freely during the sand fly activity period extending from June to October, for a natural challenge. A variety of toys and food were provided to dogs and enrichment activities were conducted in the shelter. Dogs were not treated against sand fly bites during their exposure in the field.

Concomitantly with dog’s exposure, we assessed the densities of P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi as well as their infection prevalence with L. infantum during the exposure periods as described previously43. Sandflies were collected using CDC Miniature Light Traps (John W. Hock Company, Gainesville, USA) placed inside the dogs’ boxes. Collected sandflies were pooled (maximum of 30 sandflies per pool) according to trapping origin and sex. Sandflies’ pools were processed for the presence of Leishmania parasites. The minimum infection rate (MIR) of sandflies by Leishmania parasites is defined as the number of positive pools divided by the total number of tested specimen × 10044.

At the end of the exposure period, dogs were returned to the kennel of Pasteur Institute of Tunis, in the governorate of Tunis, non-endemic for L. infantum transmission. Blood samples collected from dogs at different time points: (1) immediately at return from the field, were used to measure the IgG anti- SGH, (2) three months post-exposure, were used to evaluate the biochemical and hematological parameters and (3) six months post-exposure, were used to determine the parasite load. Spleen aspirates collected under aseptic conditions from dogs at 6 months post-exposure, were examined for the presence of Leishmania parasites.

Humoral anti-SGH antibody response in dogs following natural exposure

Specific IgG antibodies anti- P. perniciosus saliva were measured using ELISA according to Martin-Martin et al.45 with minor modifications. The wells were coated overnight with SGH of laboratory-colonized F13 females P. perniciosus (0.5 glands per well) in 0.1 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 4 °C. The wells were then washed in phosphate buffer (PBS) with 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with 6% skimmed milk diluted in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at 37 °C to block free binding sites. After washing, diluted sera (1:250) were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. Antibody-antigen complexes were detected using peroxidase-conjugated anti-dog IgG antibody diluted at 1:10,000 (Sigma-Aldrich), for 1 h at 37 °C and visualized using orthophenylendiamine (OPD) in citrate buffer and hydrogen peroxide. The absorbance was measured using an automated ELISA reader at 492-nm wavelength. Each serum was tested in duplicate.

Anti-Leishmania humoral responses in dogs

Total IgG anti-SLA were measured using ELISA previously optimized for the SLA concentration, the dogs’ sera dilution and the anti-dog IgG dilution. Different concentrations (2 or 4 μg SLA), sera dilutions (1/250 or 1/500), secondary antibodies (1/5000 or 1/10,000) were tested and the following conditions were selected (2 μg SLA, 1/250 sera, and 1/10,000 secondary antibodies). Briefly, 96-well maxisorp Nunc-immuno plates were coated with 2 µg of SLA from L. major or L. infantum (in 100 µl of 0.1 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer [pH 9.5]) overnight at 4 °C. The plates were washed thrice with 1X PBS-T, blocked with 1% BSA PBS at 37 °C for 1 h, and then washed three times with PBS-T. Sera were diluted at 1/250 and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The plates were washed six times, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-dog total immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Sigma-Aldrich), goat anti-dog IgG1 or sheep anti-dog IgG2a (Bethyl Laboratories) was added for 1 h at 37 °C, at dilutions of 1:10,000. PBS with 3% skimmed milk was used as blocking and diluent buffer to measure titers of IgG subclasses antibodies. Reaction is revealed with TMB, and the absorbance was measured using an automated ELISA reader at 450 nm with correction at 620 nm. Each serum was tested in duplicate.

Cell culture and measurement of IFN-γ production

Heparinized blood sample (10 ml) was used for purification of PBMC using Ficoll- Paque (GE Healthcare). PBMC were stimulated in vitro with SLA at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml. Cell culture supernatants were collected at 72 h to measure IFN-γ level using the sandwich ELISA method (R&D Systems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Results were expressed as the difference between cytokine’s level produced by stimulated and unstimulated cells.

Flow cytometry analysis

PBMCs (1 × 106/ml) were stimulated for 16 h with SLA (10 µg/ml) or medium alone at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Golgi stop (BD Biosciences) was added for the last 6 h of culture. Cells were then washed and incubated with PerCP-CD3 (BD Biosciences), FITC -CD4 (eBioscience) antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C. For intracellular staining, the cells were fixed and permeabilized using BD Cytoperm/cytofix plus kit (BD Biosciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions and labeled with PE-conjugated anti-dog IFN-γ (GeneTex). Analyses were performed with a FACS Canto flow cytometer using the FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences).

Quantitative real-time assay for cytokine gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from 200 µL of spleen aspirate (SA) conserved in Trizol using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the instruction provided by the manufacturer. Potential contaminating DNA was removed by incubation with DNase I using RNase free DNase Set (Qiagen). The concentration of the extracted RNA was quantified using the Nanodrop “Thermo Scientific Multiskan SkyHigh” with A260/A280 ratios. Reverse transcription was performed using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. mRNA quantification was performed for IFN-γ, IL-10 and TNF-α, with quantitative PCR (q-PCR) using the “TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix” (Applied Biosystems). For each PCR reaction, target samples were tested with three negative controls. The PCR conditions: 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing and extension at 60 °C for 1 min. Specific canine primers and hydrolysis probes for amplifying cytokines were selected based on literature (Supplementary Table 1)46,47. Quantity of mRNA was firstly normalized referring to the expression of an endogenous control Beta-actin housekeeping gene47 given by the formula 2-ΔCT (ΔCT is the difference in threshold cycles for target and reference). Results are expressed as fold increase given by the formula 2–ΔΔCT (ΔΔCT is the difference in ΔCT for target and six healthy dogs’ SA).

Quantitative real-time PCR assay for parasite load

Total DNA was extracted from 200 µL of buffy coat (BC) or spleen aspirate (SA) using the QI Amp DNA blood mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the instruction provided by the manufacturer. The concentration of the extracted DNA was quantified using the Nanodrop “Thermo Scientific Multiskan SkyHigh” with A260/A280 ratios. Real-time PCR was carried out to amplify Leishmania DNA on BC and SA samples to identify possible infection in animals. Samples were evaluated by quantification of the KMP-11 (Kinetoplast Membrane Protein) gene encoding for a protein abundantly expressed in promastigotes. The PCR reaction was performed using a Taq-Man PCR kit (Applied Biosystems). The upstream and downstream primer sequences of KMP-11 were as follow: 5’-CGCCAAGTTCTTTGCGGACAAG-3’ and 5’- TGTGTGCTCCCT GATCATGCG- 3’, respectively. A fluorogenic probe 5’FAMCGCCCGAGATGAAGGAGCACTACG–BHQ-1-3’. Each q-PCR reaction was set in a total of 25 μL each, containing 50 ng of template gDNA, 0.3 μM of each forward and reverse primer, 0.1 μM fluorogenic probe. In addition, a “no template” control in duplicate was included on each plate to prove absence of contamination. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. Parasite number within (BC) or (SA) samples was determined using a standard curve of Leishmania genomic DNA (4.109 L. infantum promastigotes). All samples with CT > 37 were considered negative and a minimum of two copies of the KMP-11 gene was detected. CT values from all samples were plotted on the standard curve to determine the parasite load.

Dogs’ status following natural exposure

Eighteen months after the third exposure, dogs’ status was evaluated based on the physical examination and the detection of Leishmania parasites within blood and/or spleen aspirate. Dogs were classified as follow: Healthy (no Leishmania detected and no clinical sign), Asymptomatic (detection of Leishmania without any clinical sign), Oligosymptomatic (detection of Leishmania with clinical score CS ≤ 3/a maximum of three abnormal clinical signs attributable to CVL) or, Symptomatic (detection of Leishmania with clinical score CS > 3/more than three abnormal clinical signs attributable to CVL)48.

Statistical analysis

Statistical level of significance between different groups was calculated using Mann-Whitney U test with GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. The difference was considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. To calculate the vaccine efficacy (VE), we used the following formula: VE = (1-OR) x100)49. The odds ratio (OR) is calculated by the formula OR = ad/bc, where a is the number of CVL cases in the vaccinated group, b is the number of non-CVL in the vaccinated group, c is the number of CVL cases in the control group, and d is the number of non-CVL in the control group.

Responses