LMX1B haploinsufficiency due to variants in the 5’UTR as a cause of Nail-Patella syndrome

Introduction

Nail-Patella Syndrome (NPS, OMIM 161,200) is a rare genetic multisystem condition with an estimated frequency of 1 in 50,000 live births. Nails dysplasia and skeletal anomalies involving the elbow, knee and the presence of iliac horns, represent the pathognomonic signs of the syndrome.

Other clinical features are represented by kidney issues like proteinuria and/or hematuria, with 30–50% of patients developing a peculiar glomerulonephritis that can lead to end-stage renal failure; eye problems, like glaucoma or cataracts, and neurological symptoms have also been described1,2,3,4.

NPS is due to alteration of the LIM-homeodomain transcription factor 1 beta gene (LMX1B, OMIM #602575) and is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition with full penetrance. However, the clinical presentation varies greatly between individuals, even within the same family4,5.

LMX1B encodes a LIM-homeodomain transcription factor. The protein is composed by two LIM domains (LIM-A and LIM-B) involved in protein–protein interactions and by a homeodomain (HD) important for the DNA binding and the transcriptional activation function. During development LMX1B plays a crucial role in limb dorsalization, kidneys, eyes and neuronal differentiation3,6,7.

NPS is caused by haploinsufficiency due to heterozygous loss-of-function alteration of the LMX1B gene. 85% of the patients carry point mutations or small indels affecting the LMX1B coding sequence, whereas in around 15% of the cases a total or partial deletion of the gene is present8,9. Chromosomal rearrangements involving the LMX1B locus have been also described10,11. Moreover, specific LMX1B missense variants such as the R246Q/P affecting the homeodomain, have been associated with familial cases of isolated Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis 10 (FSGS10, OMIM #256020) in the absence of extra-renal malformations12.

In a publication by Ghoumid et al.4, the molecular characterization of a cohort of patients from 55 unrelated families with recurrence of NPS, led to identification of NPS patients apparently negative for variants or rearrangements of the LMX1B gene. Therefore, the presence of unidentified variants within the LMX1B locus or a possible genetic heterogeneity was postulated for the first time.

More recently, two families were described carrying a heterozygous deletion in the Lmx1b-associated cis-regulatory module LARM1/LARM2, a highly conserved long-distance enhancer of the LMX1B gene that intervenes during the LMX1B-mediated limb dorsalization by amplifying LMX1B expression13,14. Patients carrying the alteration of this limb-specific functional element were reported as having a mild form of NPS, with limbs and nail restricted phenotypes without renal or ophthalmological features13,14.

In the present work, we describe two unrelated NPS familial cases, negative for variants or rearrangements affecting the LMX1B coding sequence, caused by heterozygous novel variants affecting the 5’ Untranslated Region (5’UTR) of the gene. We show that both variants introduce two novel upstream Open Reading Frames (uORF) and by a functional characterization we demonstrate that they impair the expression of the LMX1B mutated allele.

Results

Identification of novel variants of the LMX1B gene in two unrelated familial cases of NPS

Patient 1 (B481) is a 44-year-old man, first son of non-consanguineous parents, with a classical presentation of NPS including nails hypoplasia, triangular lunula, patellar dislocation, iliac horns, glaucoma, mitral valve prolapse, asymptomatic proteinuria and micro-hematuria. The family history reveals that some relatives had similar clinical features (Fig. 1a). In particular, the proband’s father (indicated as C007) has nails hypoplasia, triangular lunula, lateral patella dislocation, glaucoma and proteinuria. The mother is unaffected. The other members of the family reported as affected with NPS were unavailable for the study.

a Pedigrees of the two reported families with recurrence of NPS. Black filled symbols represent individuals affected with NPS, the arrows indicate the two probands (B481 and E477). The individual indicated by the gray symbol in Family 2 is affected by a genetic condition not related to NPS (see text for details). b Chromatograms obtained by Sanger sequencing of the 5’UTR region spanning the two identified variants of the LMX1B gene, the −174C>T in Family 1 (absent in the C008 unaffected mother) and the −226G>A in the proband of Family 2 (E477) and in her affected brother (II-3, 0032). Image created with BioRender.com.

Due to the clinical presentation of the proband B481, a clinical diagnosis of NPS was suggested and the analysis of the LMX1B gene was requested. The molecular screening of the eight coding exons and of the whole 1, 4, 5 and 7 introns was negative. The detection of different common SNVs in a heterozygous state in introns 2, 3 and 6 indirectly excluded the presence of deletions in these regions. Both MLPA and CGH array analyses were performed and were negative. To exclude chromosomal rearrangements involving LMX1B, conventional cytogenetic analysis was performed which revealed a 46, XY karyotype.

We thus extended the molecular analysis to the 5’Untranslated region (5’UTR) and to the proximal promoter region as described by Dunston and coll15. This analysis revealed the presence of a heterozygous variant in position c.−174C>T (NM_001174147.2:c.−174C>T, Supplementary Table 2) and segregation analysis confirmed the presence of the variant in the affected father (Fig. 1b). This variant is absent in dbSNP, gnomAD and ClinVar databases and has never been described in the literature.

Patient 2 (E477) is a 65-year-old woman. Her clinical features include patella hypoplasia, nails dysplasia (hands & feet), iliac horns, thin dental enamel, and diabetes. Within her family, seven among her brothers and sisters, the mother and other members of the family were reported as affected by NPS but were unavailable for the current study (Fig. 1a). The molecular screening of the LMX1B coding exons was negative. LongPCR and CGH array analyses excluded the presence of deletions of the gene.

The molecular screening of the 5’Untranslated region (5’UTR) and of the proximal promoter region revealed the presence of a never reported heterozygous variant c.−226G>A (NM:001174147.2:c.−226G>A, Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 2). While this manuscript was in preparation, a proband’s brother (II-3, #0032) came to our attention. He presented with dysplastic nails and patellar hypoplasia, without walking impairment and, at this moment, no kidney involvement. We verified the segregation of the −226G>A substitution and found that he is heterozygous for the variant (Fig. 1b). This patient has an apparently healthy child, a daughter referred with clinical signs of NPS, and a boy affected by type I Mucopolysaccharidosis with a confirmed molecular diagnosis (III-2 gray symbol, homozygous for a variant of the IDUA gene).

Due to the importance of 5’UTR sequences in regulating gene expression at post transcriptional level by different mechanisms and to assess a possible pathogenic role, we undertook a functional characterization to evaluate the impact of the two variants on the expression of the LMX1B gene.

The 5’UTR of the LMX1B gene

The identification of the promoter region and of a transcription start site16 of the LMX1B gene, allowed to define a relatively long 5’UTR region of around 1.2 kb (compared to the median length of approximately approx. 218 nucleotides in humans17). The sequence contains several GC stretches accounting for the 74% of nucleotides content.

As schematically represented in Fig. 2a, the region harbors two small upstream Open Reading Frames (uORFs) entirely contained in the 5’UTR: the first one in position −570 consists of 24 bp (uORF1); the second at –484 of 15 bp (uORF2) and may potentially be translated in micropeptides of 7 and 4 residues, respectively.

a Schematic representation of the LMX1B mRNA. The coding exons are indicated by the numbered rectangles. The light gray rectangle indicates the 5’UTR sequence harboring the wild type uORF1 and 2. The position of the identified variants is indicated by the green and red dots, respectively, and the newly generated uORF3 and 4 are also schematically represented. b Comparison between the canonical Kozak sequence around ATG with that surrounding the main LMX1B starting codon, and those in which each newly generated ATG is embedded (LMX1B −174C>T; LMX1B −226G>A). The left panel shows the sequence alignment with variant positions indicated in red. The right panel provides the values indicating the strength of each translation starting codon as predicted by ATGpr and NetStart tools. Values range from 0 to 1 and when greater than 0.5 predict a probable translation start site. Image created with BioRender.com.

The bioinformatic analysis, performed with the ATGpr and NetStart tools17,18, indicates that the two identified variants −226G>A and −174C>T introduce two novel ATGs potentially generating two novel ORFs upstream the main coding sequence (uORF3 and uORF4, Fig. 2). Indeed, the sequence context in which the new ATG codons are contained is predicted to be fairly in accordance with a Kozak consensus site, with a strength comparable to that of the starting codon of the LMX1B main coding sequence for the −174 C>T substitution and with a weaker, still significant value, for the −226 G>A variant (Fig. 2b).The two, newly generated, predicted uORFs show the same coding frame each other and are out-of-frame compared to the LMX1B main coding sequence that they partially overlap, with the generation of an early stop codon in exon 3 of the gene.

The expression of aberrant transcripts of 666 and 615 bp respectively, derived from the two predicted uORFs, may trigger a nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the corresponding mRNA. On the other end, the two novel uORFs may be potentially translated in mutant proteins of 221 and 204 amino acids, respectively (Fig. 2a). In both cases the presence of the two substitutions may likely impair the expression or function of the variant carrying transcripts or protein products.

Analysis of LMX1B cDNA

During the post-natal life, the LMX1B gene expression is restricted to specific tissues often poorly accessible3. We generated immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines from PBMC obtained from patient 1 and his parents and, as these cells do not express the gene, we set up a protocol to induce LMX1B expression and perform functional studies.

Histone acetylation, dynamically controlled by the activity of histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase (HDAC), is one of the epigenetic mechanisms involved in regulating gene expression through modification of the chromatin status: whereas acetylation correlates with nucleosome remodeling and transcriptional activation, deacetylation of histone tails induces transcriptional repression through chromatin condensation19. Therefore, pharmacological agents able to inhibit the function of HDAC may generally promote transcriptional activity19,20. Thus, we decided to test different HDAC inhibitors with the purpose of inducing LMX1B gene expression in lymphoblasts and analyze its mRNA. As shown in Fig. 3a and in Supplementary Figure 1 we were able to detect LMX1B transcript in cells treated 24 h with 10 mM of Sodium butyrate (referred as NB).

a Sodium butyrate induces LMX1B gene expression in lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from B481 proband and his parents (C007 and C008). Indeed, an RT-PCR product of 537 bp spanning from the 5’UTR region to exon 2 of LMX1B is well detectable in lymphoblasts treated for 24 h with 10 mM Sodium butyrate and in Hek-293 used as positive control, but not in untreated cells. The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used to check the retro-transcription efficiency. b The variant −174C>T likely impairs the expression of the carrying transcript as assessed by comparing Sanger sequencing of PCR products obtained from genomic versus cDNA. The position of the variant is highlighted by red arrows and that of the A>G polymorphism by blue stars (see text for details). Mw molecular weight, un untreated cells, NB Sodium butyrate, – PCR reaction negative control (no template). Image created with BioRender.com.

The comparison of the electropherograms obtained by Sanger sequencing of the region containing the −174C>T variant revealed that the substitution is detected as heterozygous in genomic DNA with two comparable peaks for the C and the T alleles. On the contrary, analysis on cDNA highlighted an imbalance between the peaks of the wild type and mutated allele in patient 1 and in his affected father (C007) indicating that the T allele variant is less represented than the C. The analysis has been performed on the whole cDNA sequence (Supplementary Fig. 1) and replicated in different independent experiments showing the same results. Moreover, as the affected father and the unaffected mother were found to be heterozygous for a common polymorphism (rs2277158) in exon 3, we could verify that the G allele in cis with the variant −174C>T is less represented in the father, while the heterozygosity is still well detectable and balanced, both in genomic and cDNA, in the mother (blue stars in Fig. 3b).

These results prompted us to hypothesize a possible defect in the expression of the variant carrying transcripts.

Functional characterization of the new variants in the 5’UTR of LMX1B gene

In the light of the results obtained in induced lymphoblasts and the hints from the in silico analysis of the 5’UTR sequence, we decided to investigate in more details the potential impact of the variants at post transcriptional level by designing two different assays. We first generated reporter gene constructs with the LMX1B 5’UTR region, wild-type and mutated versions, upstream the luciferase reporter gene in the pGL3 Promoter Vector. By this strategy, the expression of the reporter gene is driven by the SV40 promoter and the 5’UTR sequence is included in the mature mRNA. After transfection in Hek-293 cells, the luciferase activity resulting from the expression of the different constructs was measured (Fig. 4a). Any variation compared to what is observed with the wild type can be considered as a measure of the variant’s impact on the expression of the reporter gene at post-transcriptional level. As shown in Fig. 4b, the presence of the wild-type LMX1B 5’UTR stabilizes the expression of the reporter gene compared to what observed with the empty vector. The presence of the variants causes a statistically significant reduction in the Luciferase activity, albeit with different extent, 95% for the −174C>T variant and around 47% for the −226G>A, suggesting that both variants may impair gene expression.

a Workflow for the functional study of LMX1B 5’UTR variants at post transcriptional level as assessed by reporter gene assay (see text for details). b Histograms represent the luciferase activity measured after transient transfection of the different pGL3.PV expression constructs, schematically reported on the left part of the panel. The luciferase values were normalized for transfection efficiency by co-transfection with a Renilla reporter control construct (see Methods for details) and are represented as the fold activation compared to the vector carrying the WT 5’UTR of LMX1B (value 1). Values represent the mean +/−the standard deviation of at least n = 4 biological replicates performed in technical triplicate or quadruplicate (p < 0.001***). EV, luciferase reporter vector without the 5’UTR sequence; WT, wild-type LMX1B 5’UTR. c Workflow for the functional study of LMX1B 5’UTR variants at post transcriptional level as assessed by western blot analysis (see text for details). d Hek-293 cells were transfected with pRP containing the LMX1B cDNA with or without the 5’UTR sequence, wild type or mutated. The expression level of the protein was evaluated by Western Blot, by using anti-Flag and anti-LMX1B primary antibody. Arrows indicate the band corresponding to LMX1B protein (60 kDa) and a non-specific band appearing only in cells transfected with the 5’UTR constructs. Densitometric analysis of LMX1B protein levels was obtained by the anti-Flag and anti-LMX1B normalized on the signal derived from anti-GAPDH antibody. Histograms represent the mean +/− the standard deviation of 6 independent experiments and represent the values compared to the vector without the 5’UTR (value 1). p < 0.01§, p < 0.001# (Fig. 5d right panel). un, untransfected cells; no UTR, vector containing the LMX1B cDNA without 5’UTR sequence; UTRwt, expression vector containing the LMX1B cDNA with the wild type 5’UTR sequence; UTR−174, expression vector carrying the 5’UTR −174C > T variant; UTR−226, expression vector with the 5’UTR −226G>A substitution. Image created with BioRender.com.

These data were corroborated by the protein analysis in heterologous expression assays in Hek-293 cells. Indeed, we generated then a second series of expression plasmids has been obtained by subcloning in the pRP-CMV vector the whole LMX1B cDNA comprising a fragment of the 5’UTR sequence (WT and mutated) spanning the region harboring the identified variants. The cDNA lacks the native STOP codon to allow the fusion with a Flag epitope suitable for western blot analysis; the expression is under the control of a CMV promoter (Fig. 4c). After transient transfection in Hek-293, cells were processed to quantify the expression of the LMX1B protein.

As reported in Fig. 4d, we found a statistically significant reduction in LMX1B protein expression in presence of the variants as assessed by Western Blot analysis and densitometric analysis of the immunobands (Fig. 4d, right panel).

Role of NMD in the degradation of the altered LMX1B transcripts

The expression of the two novel uORF3 and uORF4 in the 5’UTR of the LMX1B may lead to the synthesis of aberrant transcripts with an early stop codon in the third coding exon of the gene, which in turn may be subjected to degradation by a nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) process. Therefore, we verified in the available lymphoblasts from Family 1 whether the treatment with Puromycin, which is a known inhibitor of NMD in these cells21, could rescue the expression of the transcript carrying the variant allele. As reported in Fig. 5a, LMX1B expression is readily detectable in cells treated with Sodium Butyrate (NB), and slightly increased by the cotreatment with Puromycin. According to Sanger sequencing results, the rescue in the expression of the variant carrying transcript is detectable as recovery of the heterozygosity in cDNA. This effect was observed both in proband B481 and in the affected father (C007), by analyzing both the −174C>T variant and the common polymorphism in exon 3 (rs2277158). The treatments did not affect the expression of LMX1B in the unaffected mother (C008), used as a control (Fig. 5b).

a Lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from B481 proband and his parents (C007 and C008) were treated 24 h with 10 mM of Sodium butyrate and overnight with 200 µg/ml of Puromycin. cDNA was obtained after retro-transcription of 2 µg of RNA and a fragment including the 5’UTR region and the first 4 exons of LMX1B was amplified by PCR. The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used to check the retro-transcription efficiency. b Details of the electropherograms showing the variant −174C>T with (NB/P) or without (NB) the cotreatment with Puromycin. The position of the variant is highlighted by red arrows and the polymorphism rs2277158 A>G by blue stars. un untreated cells, NB Sodium butyrate treated cells, NB/P cells treated with Sodium butyrate and Puromycin, mw molecular weight, – PCR no template control. Image created with BioRender.com.

The role of the newly generated upstream Open reading Frames (uORF3 and uORF4)

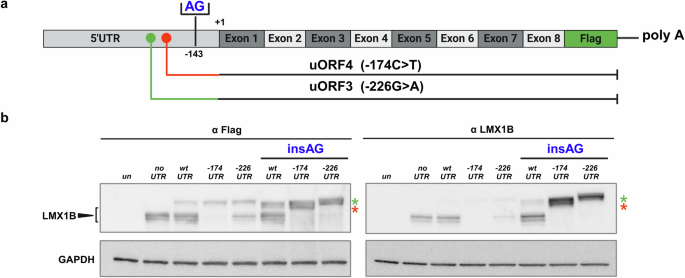

The data from the in silico analysis predicted that the ATG codons introduced by the two variants may be recognized by the cell translation machinery at expense of the canonical LMX1B starting codon. To verify this hypothesis, we designed new expression vectors in which the insertion of two nucleotides (AG) in the 5’UTR at position −143 put the two newly generated uORF 3 and uORF4, in frame with the main LMX1B coding sequence as represented in Fig. 6a. By this approach, we could demonstrate that the ATG codons introduced by the two variants may be efficiently used by the cell (Fig. 6b) to express an aberrant protein, that in this artificial condition is represented by an LMX1B protein with a higher molecular weight due to the presence of additional residues at the NH3 terminus.

a Schematic representation of the strategy we applied to investigate the expression of the new uORFs. We inserted two nucleotides (AG) in position −143 upstream the main LMX1B ATG, to put the new uORFs in frame with the main one in pRP-CMV/5’UTR (hLMX1B) expression vectors, WT and mutated versions. b After transfection of the different plasmids in Hek-293 cells, the expression of the different proteins was evaluated both with anti-LMX1B antibody (left panel) and an anti-FLAG antibody (right panel). The black arrowhead indicates the LMX1B protein and the red and green stars the products of the uORF3 and uORF4 translation when they are placed in frame with the principal ATG. The blot image is representative of three independent experiments. un, untransfected cells; noUTR, vector containing the LMX1B cDNA from ATG; UTRwt, vector containing the WT 5’UTR region and the cDNA of LMX1B; UTR−174, vector containing the −174C>T variant; and the cDNA of LMX1B; UTR−226, vector carrying −226G>A substitution; insAG, expression vectors with the AG insertion in position −143. Image created with BioRender.com.

The fact that the ATGs generated by the two variants may be efficiently recognized and used by the cell, implies that if a fraction of transcripts generated by these uORFs escapes from the NMD degradation, completely aberrant proteins may be translated at expenses of the canonical LMX1B protein.

Discussion

NPS is a rare genetic disease, inherited as an autosomal dominant condition due to loss-of-function of the LMX1B gene. Most patients carry variants affecting the coding sequence or deletions involving a part or the whole gene leading to LMX1B haploinsufficiency.

In this work, we characterized two familial cases of NPS with novel variants affecting the 5’UTR sequence.

UTRs at the 5’ and 3’ end of genes are included in the mature mRNA but are non-coding and do not directly contribute to the protein sequence. Their presence introduces a further level in the control of gene expression at post transcriptional level by different mechanisms and interactions17.

Focusing on 5’UTRs, in eukaryotes translation typically starts at the 5′ end of the mRNA, which harbors the 5′ cap and a UTR as the entry point for the ribosome. The ribosome scans this sequence to identify the starting codon and proceed with the synthesis of the protein22. The efficiency of this process may be modulated by different mechanisms: for example, a high GC content and a highly negative folding free energy can promote the acquisition of tri-dimensional structure causing the stalling of the ribosome23. Besides the presence of peculiar 3D structures also other elements such as the presence of IRES sequences, that promote the ribosome binding; the specific sequence context in which the main ATG is embedded (eg. Kozak consensus sequence) and the presence of uORFs play a crucial role22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Regulation of gene expression at post transcriptional level represents a fast and finely tuned process that allowed cells to quickly modulate the protein expression profile as required.

Pathogenic variants in the 5’UTR sequence of disease genes have been already reported as impairing the expression of essential proteins by different mechanisms including creation of novel initiation codons, splicing alteration or by modulating mRNA stability and accessibility to the translation machinery at post-transcriptional level31,32,33.

Our experimental data demonstrated that the two variants identified in the 5’UTR of LMX1B significantly impair the expression of the gene thus causing NPS.

LMX1B shows a restricted expression profile in the post-natal life, and blood cells, the only biological sample available for our study, does not express the gene. Therefore, to start the functional analysis we set up a protocol to induce the LMX1B transcription by using different chromatin modifier agents and we found that treatment of patients and control lymphoblasts by Sodium Butyrate (NB) efficiently induced the expression of the gene allowing to detect a differential expression of the transcripts carrying the −174C>T variant, thus encouraging further studies.

Functional characterization in heterologous systems, by reporter gene assays and by western blot analyses demonstrated that both the −174C>T and the −226A>G variant could significantly reduce the protein expression by acting at post-transcriptional level.

In silico analysis showed that the two variants lead to the generation of ATG codons with definition of two novel uORFs. Due to the absence of a stop codon before the LMX1B natural translation initiation site, the two mutant ORFs resulted to be overlapping and out-of-frame with the natural ORF of the gene, while being in frame each other.

The presence of uORFs can impair expression of proteins by different mechanisms: by acting like a roadblock for ribosomes; by targeting the altered mRNA to degradation by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) processes34; by leading to the translation of aberrant proteins; by coding for micro-peptides that may directly impair translation of the main ORF or may have distinct roles22,30,35,36.

The 5’UTR variants of LMX1B described in this work generate two frameshifts overlapping ORFs with an early STOP codon in the third coding exon of the gene. Therefore, we hypothesized that this might target the variant-carrying transcripts to NMD. To demonstrate this hypothesis, we co-treated available lymphoblasts from the members of the Family 1 (−174C>T variant) with NB to induce LMX1B expression and with Puromycin to inhibit NMD as previously described21. We could thus observe a rescue in the expression of the variant allele detectable as recovery of a balanced heterozygosity with both the C and T peaks equally detectable at the Sanger sequencing of the RT-PCR products. We could not perform this analysis for the second variant (−226G>A) due to the unavailability of samples from Family 2; however, it is likely that also this substitution, which generates a longer uORF overlapping the one generated by the 174C>T variant, might behave in the same way.

We further investigated the fate of the portion of transcripts eventually escaping to NMD. Our analysis suggested that the novel upstream starting codons generated by the two LMX1B variants reside in a positive Kozak environment24 that may support their recognition by the translational cell machinery. To demonstrate this observation, we generated cDNA constructs carrying a 2-bp insertion in the 5’UTR thus putting the two ATGs in frame with the main LMX1B ORF thus making it possible to detect the eventual synthesis of NH3-ter elongated proteins by western blot analysis. Our data showed that indeed both ATGs may be recognized and used by the cell at expenses of the main LMX1B starting codon.

uORFs often act as a brake on protein production and our data demonstrate that the two identified LMX1B variants generated uORFs impairing protein expression. Around half of human genes have uORFs in their 5’UTR, and these uORFs generally lead to reduced protein levels27. Further evidence supporting a functional role of these elements is provided by the fact that variants creating novel ATGs in 5’UTR of genes are less frequent than expected suggesting a negative selection constraint37.

The role of uORF creating variants has been already described as a cause of genetic diseases32,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. Often these findings have been obtained by deep analysis of specific genes, whereas in general 5’UTR remain typically poorly assessed either in clinical and research settings and are excluded in most exome capture design applied in whole exome sequencing analysis. Moreover, despite the increasing interest about the role of non-coding sequences and the development of dedicated annotations tools, validation by functional studies is still a crucial requirement, especially when such results are obtained in a diagnostic setting and may be used for genetic counseling37.

In conclusion, we demonstrated for the first time the pathogenic role of variants affecting the 5’UTR of LMX1B. Our functional characterization provides evidence that these variants may lead to LMX1B haploinsufficiency by impairing gene expression at post transcriptional level thus causing NPS. Moreover, this highlights the importance of including non-coding regions with regulatory function on gene expression, such as 5’UTR sequences, in the screening of dosage sensitive, disease genes.

Methods

Collection of peripheral blood samples, molecular and cytogenetics analyses were performed in a diagnostic procedure setting therefore, a specific written consent, approved by the appointed office of the IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, to perform these procedures and genetic tests has been administered to and signed from all the individuals (patients and relatives) included in this study. A further written consent to perform functional studies of the identified variants and to publish results was also specifically obtained from all the participants. All the signed documents are filed in each patient’s medical record. We have complied with all the relevant ethical regulations including the Declaration of Helsinki.

LMX1B screening and molecular analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified with the Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). The eight coding exons and flanking intronic sequences of LMX1B (Mane Select NM_001174147.2; NP_001167618.1), were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from genomic DNA (the oligonucleotides sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1) by using the GoTaq Master mix (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) and reactions carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 2720 Thermocycler (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA).

PCR products were cleaned-up by Exo/SAP-IT (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) digestion before direct sequencing with a Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit according to the provided protocol; sequencing reactions were run on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) and the output analyzed by the Sequencher 4.7 software (Gene Codes Corporation, Michigan, USA). Sequence variations were described according to the Human Genome Variation Society guidelines (hgvs-nomenclature.org).

Available members of Family 1 patient 1 (B481), father (C007) and mother (C008) were also analyzed by Exome Sequencing (ES). However, no significant pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified.

Cytogenetics studies

Standard karyotyping for patient 1 was already available from another clinical center and found to be negative. MLPA with exons specific probes (P289-LMX1B, MRC-Holland, Netherlands) were carried out for patient 1 (B481), according to manufacturer’s protocol. CGH array by using Cyto 4 × 180 K CGH Microarrays (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) and a longPCR-based strategy (not shown) were applied to evaluate the presence of possible duplications/deletions for patient 2 (E477).

Induction of LMX1B mRNA expression

Lymphoblastoid cell lines of patient 1 and his parents were obtained by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) immortalization of lymphocytes extracted from peripheral blood by a standard procedure. To induce LMX1B gene expression, 8 × 106 lymphoblastoid cells were treated with 10 mM of Sodium butyrate (CAS n°126-54-7, Enzo, 81 Executive Blvd Farmingdale, NY) for 24 h and processed for RNA extraction.

To inhibit the nonsense mediated mRNA decay (NMD), lymphoblastoid cells were co-treated with Sodium butyrate for a total of 24 h and over-night with 200 µg/ml of Puromycin (CAS n°58-58-2, InvivoGen, France).

LMX1B complementary DNA (cDNA) was obtained by the retro-transcription of 2 µg of total RNA, extracted with the RNeasy plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), by using Advantage® RT-for-PCR (Takara, Shiga, Japan) and subsequently, amplified by GoTaq Master mix or GoTaq Long Master mix (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol (Supplementary Table 1 for oligonucleotides used to analyze cDNA).

Plasmids construction

To study the effect of variants at the post transcriptional level, we generated a donor construct carrying a fragment of 1425 bp that includes the minimal promoter region and the whole 5’UTR of LMX1B (chr9: 126,613,038-126,614,462; GRCh38/hg38) according to the results by Dunston and coll16. The genomic fragment was obtained by PCR (GoTaq Long Master mix, Promega, Wisconsin, USA) from patients 1, 2 and from a control individual, and inserted in the KpnI and HindIII sites of the pGL4.17 Luciferase expression vector (Promega, Wisconsin, USA).

Next, we isolated wild-type and mutated fragments of 484 bp of the LMX1B 5’UTR region upstream the canonical ATG (chr9:126,613,970-126,614,453; GRCh38/hg38) by NcoI restriction and the fragments moved in corresponding site of the pGL3 promoter vector (pGL3-PV, Promega, Wisconsin, USA).

To evaluate the effect of the variants on the expression of the LMX1B protein, a pRP plasmid containing the cDNA for human, wild-type LMX1B was purchased from VectorBuilder (Chicago, USA) without the native STOP codon, to be in frame with the 3xFLAG tag provided by the vector (pRP-CMV-hLMX1B). We then amplified a fragment of 742 bp from the LMX1B cDNA synthesized from induced lymphoblasts spanning from position −274 of the 5’UTR to the EcoRI site present in the LMX1B exon 3 (chr9:126,690,972-126,690,977; GRCh38/hg38). We thus subcloned the PCR fragment in the pCR2.1 vector (TOPO-TA cloning kit, Thermo FisherScientific, Massachusetts, USA) and we generated a 5’UTR fragment by EcoRI restriction to be subcloned in the same site of the pRP expression vector (pRP-CMV/5’UTR-hLMX1B).

To obtain the 5’UTR from patient 1, a specific couple of oligonucleotides was designed to amplify the cDNA (see Supplementary Table 1), while to generate the plasmid containing the 5’UTR with the patient 2 variant we performed a site-directed mutagenesis as already described for the pRP-CMV/5’UTR-hLMX1B (oligo listed in Supplementary Table 1).

The pRP-CMV/5’UTR-ins AG-hLMX1B plasmids characterized by the insertion of two nucleotides (AG) at position −143 from the ATG were obtained by mutagenesis, by using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent, California, USA) according to the provided protocol. All the obtained clones were checked by restriction enzyme digestion and direct Sanger sequencing.

Cell culture, transient transfection and reporter gene assays

Lymphoblasts were cultured in RPMI medium, containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), where required 8 × 106 cells were treated with NaBut +/− Puromycin as already described.

The Hek-293 cell line was already available in the laboratory, previously purchased by ATCC. Cells were routinely cultured in complete medium consisting of Essential Modified Medium (MEM) with 10% FBS. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Transient transfections for luciferase assays were performed in 96-well plates, by seeding 4 × 104/well Hek-293 cells directly in the transfection mix (reverse transfection), composed by 100 ng of the pGL3-5’UTR and 3 ng of pGL4.73 [hRluc/SV40], using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). 24 h later, cells were lysed and processed to evaluate the Luciferase activities with the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) according to manufacturer’s instruction by using Glomax Multi detection system (Promega, Wisconsin, USA).

Transient transfections to evaluate proteins levels were performed by seeding 8 × 105 Hek-293 cells in 6-well plates. The next day, we added the transfection mix composted by 2 µg of pRP constructs using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent protocol (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). 24 h after, cells were collected and processed for protein extraction.

Western blot

For the detection of the LMX1B protein, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in 1xRIPA buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% Sodium Deoxycholic, 0,1% SDS), containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors (PhosSTOP cocktail and Complete tablets, Roche, Switzerland). Protein concentration was determined by the PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and 15 µg of total lysates run onto precasted 4–15% Midi Criterion TGX-gels 18 W (BioRad, California, USA). Proteins were transferred onto Nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad, California, USA) and probed with the indicated primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, protein bands were revealed by chemiluminescence with the Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) and detected with the Uvitec instrument (Cambridge, UK). Densitometric analysis of immunobands was performed by using the Uvitec software. Primary antibodies were diluted as follows: LMX1B 1:2,000 (#13457, Cell Signaling, Massachusetts, USA); FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody 1:4000 (#F1804, Merck, Germany); GAPDH 1:20,000 (#MAB374, Merck, Germany). Secondary antibodies: Polyclonal Goat anti-Rabbit Immunoglobulins/HRP 1:20,000 for LMX1B (Dako, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) and Polyclonal Rabbit anti-Mouse Immunoglobulins/HRP 1:20,000 for FLAG M2 and 1:40,000 for GAPDH (Dako, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA).

In silico study analysis

The variants described in this work introduce two novels ATG codons. To evaluate whether they could function as start sites we used two online prediction tools: the ATGpr (https://atgpr.dbcls.jp/)15, and the NetStart (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/NetStart-1.0/)18.

Statistical analysis

Luciferase reporter gene assays were independently performed at least three times in triplicate or quadruplicate. The analysis of protein was carried out on three independent WB experiments. The Unpaired t student test was applied to verify statistical significance of the observed variations. Significant differences were given as p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001 with symbols detailed in each Figure’s legend.

Responses