Long-read sequencing revealed complex biallelic pentanucleotide repeat expansions in RFC1-related Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

The biallelic intronic pentanucleotide repeat expansion (AAGGG)exp in RFC1 was identified as the genetic cause of cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy and vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS), and late-onset ataxia in 20191,2. Since then, an expanding RFC1-related disease spectrum, including idiopathic sensory neuropathy3, Charcot-Marie-Tooth4, multiple system atrophy (MSA)5, and, most recently, Parkinson’s disease (PD)6,7, has been reported. Novel expanded repeat motifs of (ACAGG)exp, (AGAGG)exp, (AAGAG)exp, (AACGG)exp, (AGGGG)exp, (AGGGC)exp, (AAGGC)exp, complex repeat configurations of (AAAGG)(10-25)(AAGGG)exp(AAAGG)(4-6), (AAAGG)(10-25)(AAGGG)exp, and different compound heterozygotes compositions of (AAGGG)exp/(ACAGG)exp, (AAGGG)exp/(AAAGG)exp, (AAAGG)exp/(AGAGG)exp, and truncating RFC1 variant/(AAGGG)exp were reported, which reflect the genetic heterogeneity in RFC1-related diseases (Fig. 1A)8,9,10,11,12,13. Currently, the genotype-phenotype correlations and the underlying mechanisms are mostly unknown.

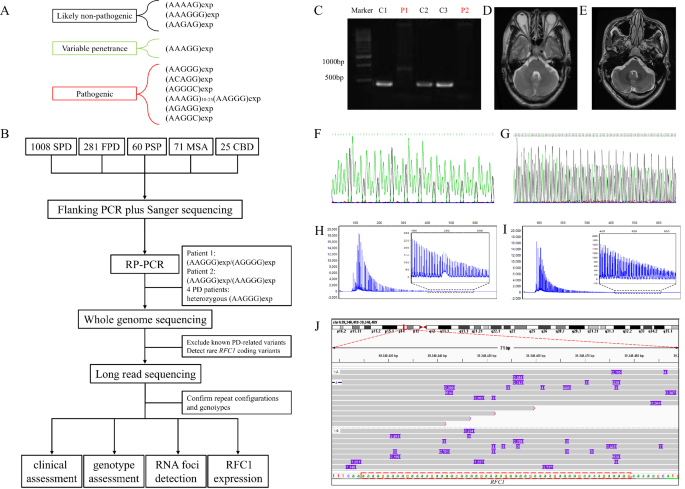

A Repeat expansion motifs at RFC1 locus. B Flow chart of this study. C The flanking PCR showed one large band in Patient 1 (P1) and an absence of product in Patient 2 (P2). C1–C3 were PD patients harboring small-band products. D MRI of Patient 1 and E MRI of Patient 2. F, G Sanger sequencing showed the (AAAAG)10 in C1 and (AGGGG)exp in Patient 1. H, I Electropherograms of RP-PCR showed that Patients 1 and 2 harbored the (AAGGG)exp. J The Integrative Genomics Viewer Snapshot of Patient 2 shows the target reads of long-read sequencing in RFC1. The number within the purple box indicates the insertion size. The red dashed box is the reference sequence of the (AAAAG) repeats in RFC1.

In this study, we report on two RFC1-related PD patients. By long-read sequencing, a novel repeat configuration of (AGGGG)exp(AAGGG)14 was detected. Meanwhile, in the expanded alleles of (AAGGG)exp, a possible somatic variant of (AAGGG)exp(AATGG)exp(AAGGG)exp was indicated. Genotypes of (AAGGG)exp with somatic (AAGGG)exp(AATGG)exp(AAGGG)exp/(AGGGG)exp(AAGGG)14 and biallelic (AAGGG)exp with its somatic variant of (AAGGG)exp(AATGG)exp(AAGGG)exp were proposed. RNA foci were detected in an (AGGGG)exp-expressing cell model, which further supported this motif as a novel pathogenic repeat motif.

Results

RFC1 pentanucleotide repeat expansion screen and clinical findings

The two-step workflow of flanking PCR plus Sanger sequencing and RP-PCR identified two early-onset PD patients suggestive of harboring biallelic repeat expansion of (AAGGG)exp/(AGGGG)exp (Patient 1) and (AAGGG)exp/(AAGGG)exp (Patient 2) in RFC1 (Fig. 1). After analyzing monogenic causes of PD as reported in previous study14, no other monogenic genetic cause (e.g., variant in PRKN, DJ1, PINK1) was detected in the two patients (by whole-genome sequencing). Four patients with PD carried heterozygous (AAGGG)exp in RFC1. However, no rare RFC1-coding region point or indel mutation was detected in the four patients with PD (by whole-genome sequencing). No RFC1 pathogenic expansion was detected in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy, MSA, or corticobasal degeneration.

Patient 1 was a 52-year-old, right-handed man of Han nationality with a high school education. The patient had no family history of PD, ataxia, or other neurodegenerative diseases. At the age of 43 years, the patient presented with resting tremor and rigidity in the right limbs, followed by the development of bradykinesia without ataxia or limb numbness or weakness. The patient responded well to dopamine replacement therapies. The MDS-UPDRS III score was 56, while the H-Y staging scale was 2.5 (Supplementary Video 1). The patient had mild cognitive impairment (MMSE score 27/30, MoCA score 24/30). According to the MDS clinical diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with clinically established PD. The head impulse test and tendon reflexes were normal. The patient also denied the presence of chronic cough, oscillopsia, or sensory impairment. Subsequent evaluation did not reveal any clinical signs of CANVAS.

Patient 2 was a 48-year-old, right-handed man of Han nationality with a high school education. The patient had no family history of PD, ataxia, or other neurodegenerative diseases. At the age of 33 years, the patient presented with resting tremor in the right limbs. As the disease progressed, the patient developed rigidity and bradykinesia, but showed no ataxia or limb numbness, or weakness. The patient also exhibited non-motor symptoms, including olfactory loss and constipation. The patient responded well to dopamine replacement therapies, which were accompanied by predictable end-of-dose wearing-off. At the age of 47 years, the patient received bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (DBS) therapy, which effectively improved motor symptoms. The patient’s MDS-UPDRS III score was 13 in both the medication state and the DBS state, while the H-Y staging scale was 2 (Supplementary Video 2). The patient had no dementia (MMSE score 27/30, MoCA score 27/30). This individual was diagnosed with clinically established PD. Subsequent evaluation revealed negative outcomes for both the head impulse test and electromyography. The patient also denied the presence of chronic cough, oscillopsia or sensory impairment. Notably, this patient did not exhibit any clinical signs of CANVAS.

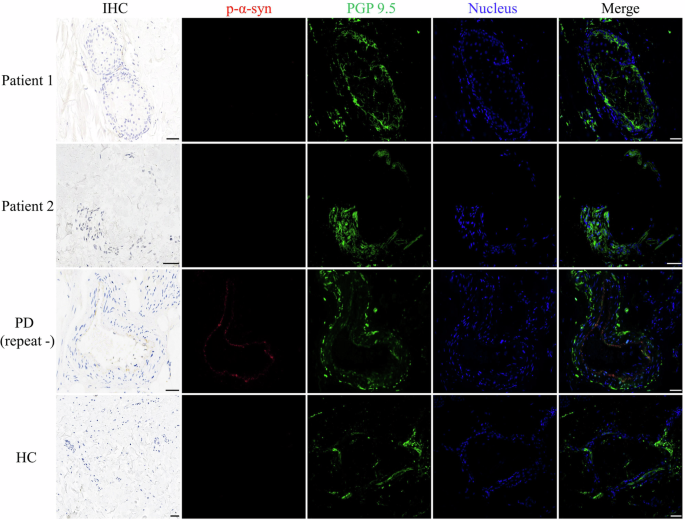

Double-labeling immunofluorescence revealed p-α-syn deposition in dermal nerve fibers in the positive PD control but not in Patient 1, Patient 2, or the healthy control (Fig. 2). This indicated a probable different underlying pathological mechanism in the two RFC1-related PD patients from that in the idiopathic PD patient.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis of anti-phosphorylated alpha-synuclein (p-α-syn) and anti-protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) demonstrated co-localization in the Parkinson’s disease (PD) patient, but not in Patient 1, Patient 2, or the healthy control. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Genotyping the RFC1-repeat expansions by long-read sequencing in the RFC1-related PD patients

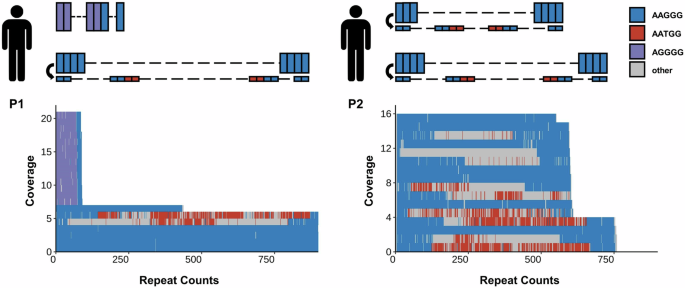

As a novel repeat motif or repeat configuration might exist and be associated with diverse phenotypes in repeat expansion diseases15,16,17,18, we applied long-read sequencing to reveal the detailed genotypes at the RFC1-repeat locus (Fig. 3). In Patient 1, the long-read sequencing suggested an allele with (AGGGG)exp(AAGGG)14 (14X coverage) and another allele with (AAGGG)exp (7X coverage). Meanwhile, the analysis revealed the presence of two subreads containing (AATGG)exp insertions within the (AAGGG)exp sequence, indicating the presence of somatic variants (Fig. 3). The detailed sequences are in the Supplementary material.

The left panel displays the genotype pattern and long-read sequencing results of Patient 1. Patient 1 harbors an allele with a (AGGGG)exp(AAGGG)14 repeat and another allele with an (AAGGG)exp repeat. Long-read sequencing analysis of Patient 1 identified 21 subreads spanning the entire RFC1 locus, encompassing expansions of AAGGG, AGGGG, and AATGG. Two subreads containing (AATGG)exp insertions within the (AAGGG)exp are detected. The right panel displays the genotype pattern and long-read sequencing results of Patient 2. Patient 2 harbors two alleles with (AAGGG)exp. Long-read sequencing analysis of Patient 2 identified 16 subreads spanning the entire RFC1 locus, encompassing expansions of AAGGG and AATGG. Six subreads containing (AATGG)exp insertions within the (AAGGG)exp from both alleles are detected. AAGGG, AGGGG, and AATGG are shown as blue, purple, and red rectangles, respectively.

It is not unique, but has its counterpart. In Patient 2, the long-read sequencing suggested two alleles with (AAGGG)exp (12X, 4X coverage). The first allele exhibited an approximate repeat expansion of 600, while the second allele displayed approximately 750 repeats. The presence of subreads containing (AATGG)exp insertions caused by somatic variants was detected in both alleles (Fig. 3).

RNA aggregates in cells overexpressing (AAGGG), (ACAGG), and (AGGGG) repeats

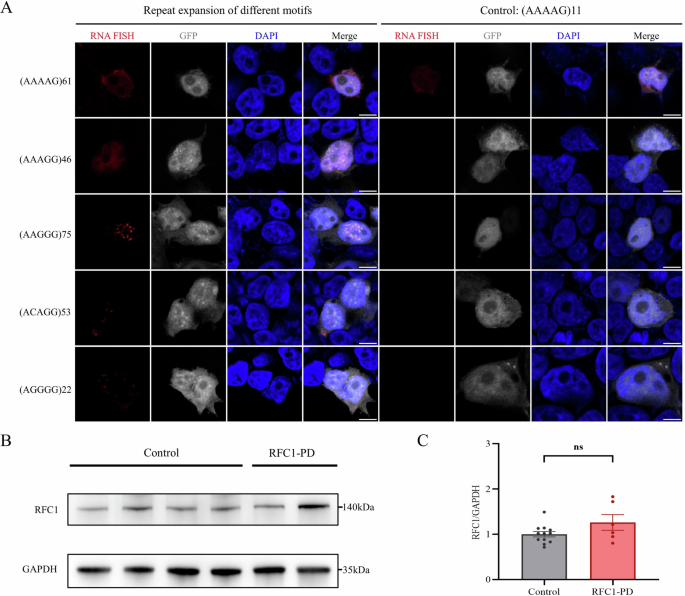

To assess whether the novel reported pentanucleotide repeat expansions in RFC1 also cause the formation of RNA aggregates, RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization was conducted in HEK293T cells following overexpression of (AAAAG)61, (AAAGG)46, (AAGGG)75, (ACAGG)53 and (AGGGG)22. (AAAAG)11 was used as a negative control.

(AAGGG) RNA foci were clearly detected in cells overexpressing (AAGGG)75 repeats (Fig. 4A). (ACAGG) and (AGGGG) RNA foci were also detected in cells overexpressing (ACAGG)53 and (AGGGG)22 repeats, respectively. The RNA foci were predominantly located in the nucleus. However, (AAAAG)61 and (AAAGG)46 repeats did not form RNA aggregates in this cellular model. These results suggested that RNA gain of function may be involved in RFC1-related diseases and that (AGGGG)exp may be a novel pathogenic repeat motif that can form RNA foci in addition to (AAGGG)exp and (ACAGG)exp.

A (AAGGG) RNA foci were clearly detected in cells overexpressing (AAGGG)75 repeats. (ACAGG) and (AGGGG) RNA foci were also detected in cells overexpressing (ACAGG)53 and (AGGGG)22 repeats, respectively. (AAAAG)61 and (AAAGG)46 repeats did not form RNA aggregates in this cellular model. B, C Western blot revealed no significant changes in RFC1 protein expression levels in the fibroblasts of RFC1-PD patients when compared to healthy controls. Three independent replicates were conducted using fibroblasts derived from the two RFC1-PD patients and four healthy controls. The bar graphs showed the mean ± SEM and a two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis. ns not significant (P > 0.05).

The expression of RFC1 in patient fibroblasts

To determine whether the above complicated biallelic repeat expansions resulted in the PD phenotype by reducing RFC1 protein expression, we collected fibroblasts from the two RFC1-related PD patients and four healthy controls. Western blot showed that RFC1 protein expression was not changed in RFC1-related PD patient fibroblasts compared with healthy controls (Fig. 4B, C).

Discussion

With expanding genetic screens of RFC1-repeat expansion in neurodegenerative diseases, more RFC1-related phenotypes are being revealed19. Studies in Western populations have demonstrated that pathogenic RFC1-repeat expansions underlie a substantial proportion of clinically suspected CANVAS1, late-onset ataxia1, idiopathic sensory neuropathy3, Charcot-Marie-Tooth4, and PD6,7,20. In contrast, the prevalence and clinical implications of RFC1-repeat expansions in Eastern populations remain less defined, with data primarily derived from limited studies from Chinese cohorts and Japanese cohorts. RFC1-repeat expansions were identified as related to PD in our study and MSA in Chinese cohorts5. No biallelic pathogenic RFC1-repeat expansion was found in our Chinese MSA cohort in this study and another Chinese MSA cohort21. Therefore, the correlation between RFC1 and MSA requires further investigation. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reported cases of CANVAS associated with RFC1 repeat expansion in the Chinese population. In the Japanese population, studies showed biallelic intronic repeat expansions in RFC1, including novel motif (ACAGG)n expansion either in the homozygous state or in a compound heterozygous state with (AAGGG)exp in patients with CANVAS10. Yuan et al. identified RFC1-repeat expansions were the primary cause of hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy22. There are significant differences in the number of patients with RFC1-repeat expansions and the types of clinical phenotypes between Eastern and Western populations. This may be due to differences in genetic backgrounds.

PD, either late or early-onset, is a novel RFC1-related phenotype that was recently reported in a Finnish population and non-Finnish European population (Supplementary Table 1)6,7,20. Our finding of PD patients with RFC1-repeat expansion in a Chinese population further confirmed this association. The currently reported eight RFC1-related PD patients responded well to dopaminergic drug therapy. Two RFC1-related PD patients (one in the Finnish cohort and one in our cohort) benefited from DBS therapy. No p-α-syn deposition in dermal nerve fibers was detected in two of our RFC1-related PD patients, suggesting a different pathogenic mechanism from that in idiopathic PD. Overall, RFC1-repeat expansion test should be recommended in more PD cohorts from different populations worldwide.

Similar to the Finnish PD cohort studies and most other RFC1-repeat expansion screen studies, our study used a genetic test of a two-step workflow of flanking PCR plus Sanger sequencing and RP-PCR, with results that only allowed us to partially infer the genotypes of the detected RFC1-repeat expansion. Thus, the genotype-phenotype correlation analysis and further pathogenic mechanism exploration are limited. To overcome this limitation, long-read sequencing was applied, and the results revealed three different genotypes of homozygous (AAGGG)exp, homozygous (ACAGG)exp, and compound heterozygotes of (AAGGG)exp/(ACAGG)exp in phenotypes of CANVAS and RFC1-related ataxia8,10. More recently, Dominik et al. also reported novel pathogenic or probable pathogenic RFC1-repeat expansions of (AGGGC)exp, (AAGGC)exp, (AGAGG)exp, and (AAAGG)(10-25)(AAGGG)exp in patients with CANVAS13. Hence, RFC1-repeat expansion presented with complex motifs. However, the detailed RFC1-repeat expansion genotypes in other RFC1-phenotypes were mostly unknown. In our RFC1-related PD patients, different genotypes were observed. In Patient 1, compound heterozygotes of (AAGGG)exp with possible somatic (AAGGG)exp(AATGG)exp(AAGGG)exp/(AGGGG)exp(AAGGG)14 were revealed. As (AGGGG)exp was only previously reported in the heterozygous state in one ataxic patient, its pathogenicity was uncertain8. (AGGGG) RNA foci, in addition to (AAGGG) RNA foci and (ACAGG) RNA foci, were observed in the constructed HEK293T cells. Thus, we proposed (AGGGG) as a novel pathogenic RFC1 repeat motif. Interestingly, biallelic (AAGGG)exp with possible somatic (AAGGG)exp(AATGG)exp(AAGGG)exp were also detected in Patient 2. This indicated that the somatic (AATGG)exp insertion in the (AAGGG)exp allele might be a key genotypic feature associated with RFC1-PD. However, it is also a main limitation in our report that the possible somatic (AATGG)exp insertion needs to be analyzed in more patients with PD or parkinsonism and reconfirmed in multiple sequencing platforms (e.g. PacBio).

The complicated genotype-phenotype correlation for the RFC1-related diseases might be associated with diverse underlying pathogenic mechanisms. Currently, gene loss of function, RNA gain of function and repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation are the three main pathogenic mechanisms for the intronic repeat expansions23,24. Interestingly, (AAGGG)exp can form G-quadruplex structures in DNA and RNA, and reduce the expression of adjacent genes in an overexpression cellular model, suggesting a potential role for gene loss of function in RFC1-repeat expansion25. Consistence with these findings, two studies reported a genotype of compound heterozygotes of truncating RFC1 variant/(AAGGG)exp in CANVAS patients, accompanied by reduced RFC1 gene expression levels11,12. However, Maltby et al. did not observe reduced RFC1 gene expression in fibroblasts and neuronal cell models derived from CANVAS patients carrying (AAGGG)exp/(AAGGG)exp26. Meanwhile, no altered RFC1 expression was detected in the fibroblasts from our RFC1-related PD patients. Additionally, the genotype of compound heterozygotes of truncating RFC1 variant/(AAGGG)exp was not detected in our PD cohort, with four patients carrying heterozygous (AAGGG)exp. Considering the above results, the involvement of gene loss of function in the pathogenesis of RFC1-repeat expansion remains unclear.

On the other hand, the G-quadruplex structures formed by (AAGGG)exp-RNA create favorable conditions for RNA gain of toxicity and RAN translation23,25. In the previous study, (AAGGG)exp/(CCCTT)exp-RNA foci were observed in SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing (AAGGG)54/(CCCTT)94, suggesting the toxic gain of function at the RNA level1. The detection of (AGGGG) RNA foci and (ACAGG)exp-RNA foci in our study further supported the role of RNA gain of function in the RFC1-repeat expansion pathogenic mechanism. To investigate whether the mechanism of repeat peptide toxicity is involved in RFC1-repeat expansion, Maltby et al. constructed an HEK293T cell model overexpressing (AAGGG)exp and detected the repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation product: lysine-glycine-arginine-glutamate-glycine (KGREG) repeat peptide26. This repeat peptide was also observed in cerebellar granule cells of CANVAS patients26. Although RNA foci and repeat peptides have been detected in RFC1-repeat expansion, their cytotoxic effects remain controversial26. We hypothesize that the diverse pathogenic mechanisms exist and interact with each other under different phenotypes and genotypes for the RFC1-repeat expansion.

The novel pathogenic RFC1-repeat expansions identified in our study provide insights into novel potential pathogenic mechanisms for RFC1-related PD. For the (AAGGG)exp(AATGG)exp(AAGGG)exp, one hypothesis is that (AATGG)exp, the identical repeat expansion as (TGGAA)exp causing SCA3127, could promote the translation of its own pentapeptide repeat protein (poly-WNGME) and (AAGGG)exp’s pentapeptide repeat protein (poly-KGREG, inferred), which might both be toxic. Another hypothesis is that (AGGGG)exp and (AATGG)exp-RNA foci sequester specific RNA-binding proteins different from those sequestered by (AAGGG)exp and (ACAGG)exp, resulting in different phenotypes of RFC1-related PD and CANVAS/RFC1-related ataxia. The above hypothesized pathogenic mechanisms associated with novel RFC1-repeat expansions are worthy of further study. The RFC1-related phenotype may not be solely associated with one pathogenic mechanism but may involve two or several pathogenic mechanisms.

In conclusion, here we reported two RFC1-PD patients and revealed their detailed genotypes. The presence of the novel (AGGGG)exp(AAGGG)14 and (AAGGG)exp(AATGG)exp(AAGGG)exp, and complicated genotypes in RFC1-related PD patients than those in CANVAS/RFC1-related ataxia indicated more complicated pathogenic mechanisms for RFC1-related diseases. Long-read sequencing in other RFC1-related diseases and further functional studies should be performed to clarify the underlying pathogenesis.

Methods

Subjects

We enrolled 1008 sporadic patients with PD and 281 unrelated probands with familial PD who fulfilled either the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) clinical diagnostic criteria28 or the United Kingdom Brain Bank criteria29 (only used prior to the release of the MDS criteria) for PD. We also enrolled 60 patients with progressive supranuclear palsy, 71 patients with MSA, and 25 patients with corticobasal degeneration, following the diagnostic criteria30,31,32.

Patients were enrolled from January 2012 to December 2022 in the Department of Neurology of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants following the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors have obtained written consent to publish the details, images, or videos.

Genetic methods

Flanking polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for each individual as previously described1. The flanking PCR products were sequenced to check if they contained both alleles. Samples lacking flanking PCR products suggested biallelic expansion that was either too large or had a high GC content to be amplified by standard PCR. Repeat primed-PCR (RP-PCR) was performed for pentanucleotide repeat expansion motifs of RFC1, including (AAAAG)n, (AAAGG)n, (AAGGG)n and (ACAGG)n.

The detailed repeat length and repeat motif in patients who had RFC1-pentanucleotide repeat expansions proved by RP-PCR were analyzed by long-read nanopore sequencing. The DNA samples were extracted from blood using the chloroform extraction method. Manual extraction was utilized to isolate DNA from cells or, in the case of tissue samples, the tissues were first ground using liquid nitrogen to facilitate cell disruption. Following cell lysis, a chloroform extraction step was performed to remove organic contaminants such as proteins, sugars, and phenols released during lysis. DNA was precipitated using isopropanol and further purified using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads. The quality of the extracted DNA was rigorously assessed using Nanodrop, Qubit quantification, conventional electrophoresis, and pulse field gel electrophoresis. 1 μg (or 100–200 fmol) of genomic DNA was subjected to end-repair and A-tailing reactions with NF water to 41 μl. The end-repair mixture, containing the necessary buffers and enzymes, was incubated under specific temperature conditions to repair damaged DNA ends and add an adenosine overhang to the 3’ ends, facilitating adapter ligation. The resulting product was purified using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads and eluted in 61 ul EB Buffer. Subsequently, sequencing adapters were ligated to the DNA fragments, and the ligation reaction was also purified using magnetic beads. The concentration of the adapter-ligated DNA was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit. Finally, the prepared DNA libraries were subjected to sequencing on the PromethION platform for 72 h on an R10.4.1 flow cell (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). ONT sequencing data were base-called using Guppy (version 5.0.13). The resulting FASTQ files were aligned to the hg38 reference genome using minimap233. Subreads that align to the RFC1 locus and contain repeat expansions were identified. The repeat size in the ONT data was determined manually due to the low coverage.

For whole-genome sequencing, DNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X according to the manufacturer’s instructions for paired-end 150 bp reads. Quality control of the resulting FASTQ files was carried out using fastp software. Paired-end reads were aligned to the UCSC hg19 reference genome using BWA-mem2, version 2.2.1. Variant calling for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, and deletions followed the best practice guidelines from the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK).

Clinical and neuroimaging assessments

Patients underwent comprehensive neurological examinations by at least two senior neurologists who specialize in movement disorders. A battery of neurological and psychological tests was conducted, including brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electromyography, head impulse test, the Mini‐Mental State Examination, and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

Skin biopsy and related histopathological feature analysis

Skin biopsies were performed as previously described34. Immunofluorescence was performed using anti-phosphorylated alpha-synuclein (p-α-syn) (ab51253; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-protein gene product 9.5 (ab108986; Abcam) antibodies as previously described34.

Cell culture

Informed consent was obtained from patients with biallelic RFC1 repeat expansion. Skin fibroblasts were obtained from skin biopsy from the above patients and cultured in DMEM (high glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (0.1 mM), GlutaMAX supplement (2 mM) and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml). HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured in DMEM (high glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml). All cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Plasmid construction and transfection

(AAAAG)61, (AAAGG)46, (AAGGG)75, (ACAGG)53, and (AGGGG)22 repeat sequences were synthesized by Genscript and cloned into the pcDNA3.1-EGFP vector. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmid transfection was conducted using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization

The 5′Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide DNA probes ([CTTTT]6, [CCTTT]6, [CCCTT]6, [CCTGT]6, and [CCCCT]6) were purchased from Tsingke (Beijing). Twenty-four hours after transfection, HEK293T cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min. Permeabilization was performed in 0.5% Triton in PBS for 5 min, and washed 3 times with PBS. Following this, the coverslips were incubated in prehybridization solution (Ribobio, C10910) for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, the probes were diluted in a hybridization buffer (Ribobio, C10910) at 100 nM and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After hybridization, coverslips were washed 3 times in Wash buffer I (4X SSC with 0.1% Tween-20), once in Wash buffer II (2X SSC), and once in Wash buffer III (1X SSC). These were then washed with PBS three times. DAPI was used for counterstaining. Images were captured by Nikon A1R confocal microscopy.

Western blot

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors for 30 min on ice. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were collected and quantified by BCA assay. Twenty micrograms of protein were separated on 4%–12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to 0.22 µm PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-GAPDH (1:1000, 2118 s, CST) and anti-RFC1 (1:1000, GTX129291, GeneTex). Membranes were then washed with TBST and incubated with HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. The bands were visualized by ECL detection. Quantification was conducted using Image J software.

Responses